Eliminating hepatitis C: Part 2. Assessing your patient for antiviral treatment

As soon as a patient is diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C, preparations can begin for treatment with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). Most patients can receive DAA treatment in general practice. GPs are ideally placed to assess their patients in preparation for DAA treatment and to identify the minority who require specialist referral.

- Most patients with hepatitis C can be treated with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) in general practice.

- GPs are ideally placed to assess patients in preparation for DAA treatment.

- Pretreatment assessment includes a comprehensive medical and social history, medication review, physical examination and investigations.

- Key questions to determine the safety of DAA treatment in primary care concern the presence of cirrhosis, hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype, hepatitis B or HIV coinfection, potential drug interactions, previous HCV treatment and renal function.

- Patients with cirrhosis, complex comorbidities or who have previously failed DAA treatment should be referred for specialist care.

With the introduction of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment in Australia in 2016, most people with chronic hepatitis C can be cured of this infection. GPs and suitably qualified nurse practitioners working in all areas of primary care have a key role in identifying, testing and treating their patients with hepatitis C.

The previous article in this series discussed how to identify your patients with hepatitis C. This article provides practical advice on assessing a patient after diagnosis in preparation for DAA treatment. This includes determining whether they can be safely treated in general practice or require specialist referral.

After diagnosis, what next?

All people diagnosed with hepatitis C should be considered for DAA treatment. DAAs have the potential to cure most people with hepatitis C and have few contraindications. As soon as a patient is diagnosed with hepatitis C, assessment for treatment can begin, in consultation with the patient.

Pretreatment assessment

Patient assessment in preparation for treatment includes:

- comprehensive medical and social histories

- medication review

- physical examination

- investigations, including a liver fibrosis assessment.

A full list of the required assessments and investigations appears in Box 1.1

Six key questions need to be answered to help determine whether the patient can be treated safely in primary care or needs to be referred to a specialist, and the most appropriate treatment option. These questions regard the individual, the hepatitis C virus (HCV) and the liver.

The key questions are:2

- Does the patient have cirrhosis?

- What is the genotype of the infecting HCV? (This requirement may be removed in the future owing to the availability of pangenotypic agents.)

- Is the patient coinfected with HIV or hepatitis B virus (HBV)?

- Are there any potential drug interactions between the patient’s current medication and the DAAs?

- Has the patient previously been treated for hepatitis C?

- What is the patient’s renal function?

An important part of the pretreatment assessment is determining the presence of advanced liver disease. Patients with cirrhosis require specialist referral and may need changes to the standard treatment regimen.

It is also important to address potential psychosocial barriers to treatment during the assessment process. Current active injecting drug use is not a contraindication to hepatitis C treatment. However, some patients may need support to stabilise drug and alcohol use or to establish adherence support services before treatment.

Vaccinations

All susceptible patients with hepatitis C should be offered vaccinations against hepatitis A and B viruses. These vaccinations are subsidised for patients with liver disease and those who are at high risk of infection in some jurisdictions.

Liver fibrosis assessment

Liver fibrosis assessment is important to determine whether the patient has cirrhosis (Flowchart).2 Although all patients are eligible for treatment, regardless of their cirrhosis status, the presence of cirrhosis determines the need for referral for specialist care and influences treatment regimen and duration in some cases, as well as follow up after treatment.1 Most patients do not have advanced liver disease and can be treated easily in primary care.

The two most widely used noninvasive methods for assessing liver fibrosis are:

- the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI)

- transient elastography, including FibroScan.

AST to platelet ratio index

The APRI has been developed as a simple serum biomarker for assessing fibrosis using results from a full blood count and liver function test. The APRI is calculated from the AST level and platelet count. APRI calculators are readily available online (e.g. www.hepatitisc.uw.edu/page/clinical-calculators/apri). Alternatively, the APRI can be calculated using the formula shown in the Figure. An APRI result of 1.0 or more indicates possible cirrhosis; the patient should be referred for further assessment including transient elastography. An APRI result less than 1.0 suggests that cirrhosis is unlikely and further evaluation for cirrhosis is usually not necessary unless clinically indicated; the patient can proceed on the treatment pathway.

Transient elastography

Transient elastography measures the stiffness of the liver, which is used to assess liver fibrosis. Threshold levels can determine the presence of cirrhosis. FibroScan is the most extensively validated and widely available method of transient elastography. It uses a series of short, pulsed, low-frequency sound waves and is similar to an abdominal ultrasound examination in terms of patient experience. FibroScan takes a trained operator (usually a nurse or doctor) 10 to 15 minutes to perform. GPs can refer patients to a liver clinic for a FibroScan. In some areas, specialist hepatology nurses offer FibroScan clinics in the community.

A FibroScan reading of 12.5 kPa or higher indicates a high likelihood of cirrhosis.3 The patient requires referral to a specialist for management and regular monitoring for complications of cirrhosis, including hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients with a FibroScan result of less than 12.5 kPa are generally suitable for DAA treatment in primary care.

Alternative methods for evaluating liver stiffness are offered by some radiology services as an add-on to a liver ultrasound examination. They include shear wave elastography and acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) imaging. These methods are convenient but less well validated in identifying fibrosis in the presence of chronic hepatitis C.1

Risk factors and signs of cirrhosis

Other clinical information should be collected to determine a patient’s risk of cirrhosis. This includes their clinical risk factors for cirrhosis and signs of advanced liver disease on physical examination (Box 2). A comprehensive patient assessment is needed because the APRI and FibroScan may not detect cirrhosis in all patients.

Drug interactions

DAAs can interact with many medications. Common examples include proton pump inhibitors, statins, ethinylestradiol and antiepileptic medications such as carbamazepine and phenytoin. The potential for interactions depends on the specific DAA. The University of Liverpool in the UK has developed a comprehensive tool for checking potential drug interactions (available online at: www.hep-druginter actions.org).

When to refer

Most patients with hepatitis C can receive DAA treatment safely in primary care (see the case study in Box 3 and the Table). Patients with cirrhosis, complex comorbidities or who have received previous failed DAA treatment should be referred for specialist care (Box 4).1,2

Appropriate specialists are those who have expertise in treating patients with viral hepatitis. This includes gastroenterologists, hepatologists, infectious diseases physicians and sexual health physicians, depending on the indication for the referral and local pathway (including telehealth or other videoconferencing consultations for GPs and patients in rural or remote areas who have limited access to specialist care).

Psychosocial assessment

When determining patient readiness for DAA treatment, GPs must take account of comorbidities, lifestyle and social issues. Major psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia or ongoing drug use (including injecting drug use) and alcohol use or being homeless can pose challenges to adherence for patients but are not contraindications to treatment. It is important to optimise the patient’s health when they are considering treatment. This may include initiating opioid substitution therapy before starting treatment and referral to support services as required.

More intensive adherence support may need to be organised before treatment. This will be covered in more detail in the next article in the series.

Conclusion

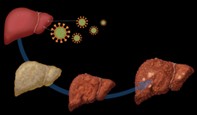

The role of GPs in managing patients with hepatitis C and preparing them for DAA treatment is crucial to the hepatitis C elimination effort in Australia. Resources on hepatitis C management for healthcare providers and patients are shown in Box 5. If left untreated, people with hepatitis C will be at increased risk of developing cirrhosis and associated complications, including liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma. Preparation for hepatitis C treatment involves a few straightforward steps. Most people diagnosed with hepatitis C can be assessed and treated in primary care, giving GPs an exciting opportunity to offer their patients a cure. MT