Intestinal failure – improving long-term survival

Chronic intestinal failure (IF) is the reduction of gut function below the minimum necessary for absorption of essential nutrients, leading to the need for intravenous support to maintain life. Most cases are due to small bowel resection; other causes include small bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease, and small bowel dysfunction. Given the chronic nature of IF, patients will likely present to general practice either undiagnosed or with complications such as central-line infection. Patients can survive for many years on parenteral support and are often able to lead almost normal lives.

- Chronic intestinal failure (IF) is a condition that necessitates parenteral support with either intravenous fluid or parenteral nutrition to maintain life. Most cases are due to small bowel resection but other causes include small bowel disease or dysfunction.

- Patients with IF can live healthy, almost normal lives for decades when managed in a specialist centre by a multidisciplinary team.

- IF may not always be recognised before the patient leaves hospital, and those with an intact colon may have an insidious progression and present with slow malnutrition. A diagnosis of IF should be considered in any patient who is slow to recover from, or deteriorates after, small bowel resection.

- Given the need for long-term venous access, central venous catheter-related bloodstream infection is the major complication of chronic IF.

- Teduglutide is a new drug that can be used to treat patients once the diagnosis is established, and works by increasing the small bowel absorptive capacity.

- Small bowel transplantation is a last resort and only performed when long-term parenteral support is unsuccessful.

Intestinal failure (IF) is a condition characterised by the inability to maintain either nutritional or hydration status by enteral intake caused by small bowel resection, disease or dysfunction.1 Acute IF is generally managed on the acute ward by either the medical or surgical teams, depending on the aetiology. Chronic IF is more likely to be encountered in the outpatient setting or community. Patients with chronic IF require parenteral support, either in the form of regular intravenous (IV) fluid or home parenteral nutrition (HPN) via a central venous catheter (CVC). Although uncommon, chronic IF results in a significant burden on patients and the healthcare system. It contrasts with intestinal insufficiency, where the reduction in the gut’s absorptive function does not require IV supplementation to maintain health and or growth.

Before the late 1960s, patients with severe chronic irreversible IF would die from malnutrition, dehydration and electrolyte disturbances. Advances in IV catheter technology allow such patients to survive long term and eventually be discharged from hospital. The first patient to be discharged and receive HPN was described by the University of Pennsylvania.2-4 Since then, the use of HPN has become established across major medical centres in the United States. The IF Unit at Fiona Stanley Hospital (FSH) in Western Australia was established in 2010; its first patient is still living on parenteral nutrition (PN), and patients established in 2012 and 2014 are living almost normal lives, with the exception of having to connect IV lines some nights of the week. Worldwide, individuals with chronic IF have survived on total PN for over 30 years.5

This article describes the different types and aetiologies of IF, with a focus on chronic IF, including the complications and recent developments in its management. Although the article discusses adult IF, many of the principles are relevant in the paediatric population.

Classification of IF

IF can be viewed as a heterogeneous group of conditions with a common treatment of parenteral support. As such, IF can be classified in several ways that are useful in understanding the condition.6

Onset and course

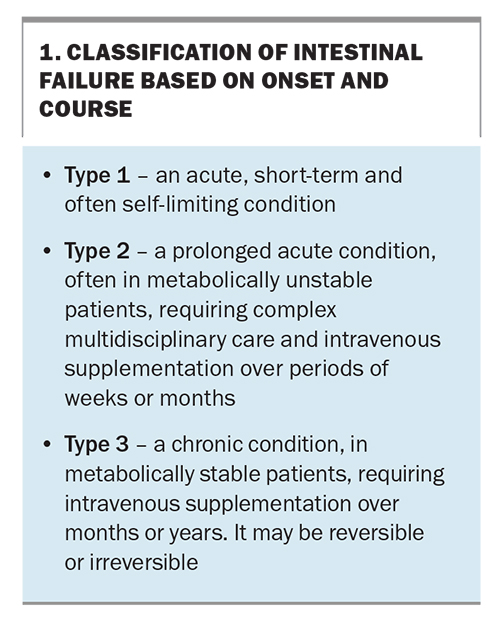

IF can be categorised clinically into three subtypes according to onset and course (Box 1).1,6,7 Type 1 is generally acute and is unlikely to be encountered in the community, as it is usually either an immediately postoperative condition managed on the surgical ward or associated with acute critical illness. Type 1 (acute) IF may take days or weeks to resolve, depending on individual factors, such as age and comorbidities, and some patients with type 1 IF may progress to type 2 IF. Type 2 IF is typically a slower-to-recover but still postsurgical condition that can last for weeks or months. Type 1 and type 2 IF have been extensively reviewed elsewhere.7,8

Type 3 IF is the longer-term chronic condition and is the focus of this article. Chronic IF is usually caused by short bowel syndrome due to small bowel resection, with dysmotility generally being the next most common cause.

Pathophysiological classification

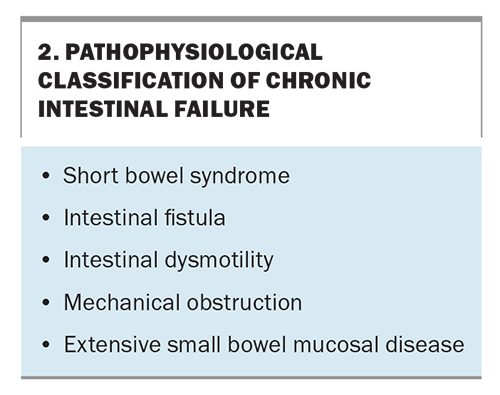

Intestinal failure can be grouped into five pathophysiological conditions that are more common to chronic IF (Box 2).6 At the time of writing, the FSH unit manages 25 patients with chronic IF: 15 with a pathophysiological classification of short bowel syndrome and 10 with intestinal dysmotility.

A UK study of 450 patients with chronic IF between 2011 and 2016 found that the underlying causes included surgical complications (28.8%), Crohn’s disease or irritable bowel disease (22.6%), mesenteric infarction or ischaemia (16.4%), dysmotility (10%), malignancy (8.4 %), radiation enteropathy (3.8%) and other miscellaneous causes (10.2%).5 Among patients in the FSH unit, the most common underlying causes are dysmotility (40%), surgical complications (20%), Crohn’s disease (16%) and ischaemic bowel (16%).

Anatomical classification

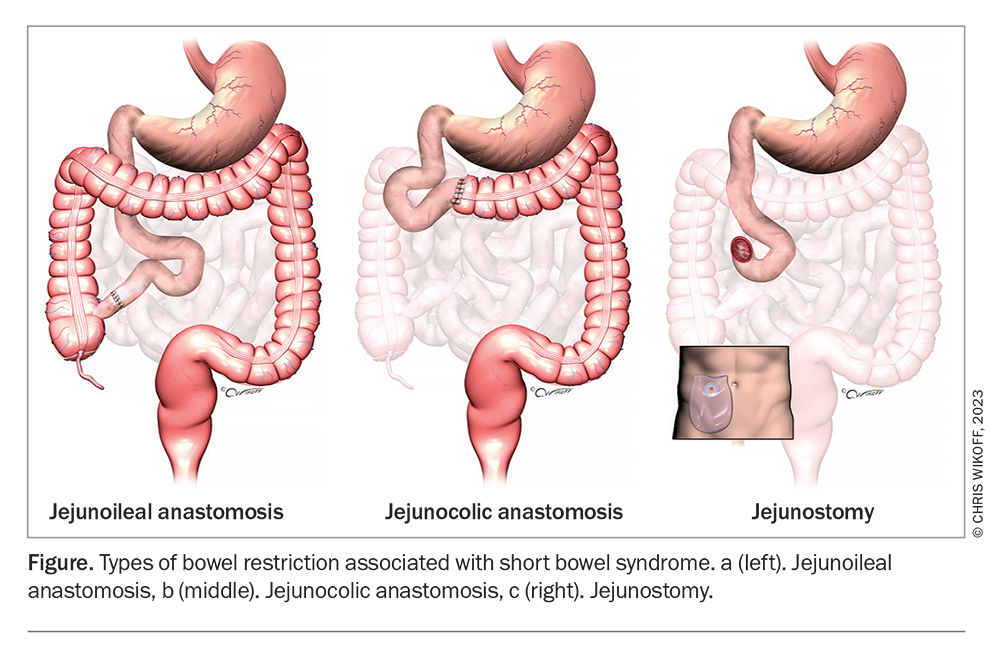

To help with diagnosis and treatment, short bowel syndrome can be further classified as follows.9

- Patients with a short bowel and an intact ileum and colon (Figure a). These patients rarely need long-term enteral or parenteral nutrition.

- Patients with a short bowel, due to removal of the ileum, and a retained functional colon (Figure b). These patients are prone to gradual undernutrition and may need to eat more than expected to maintain their nutritional needs. The condition may improve with time as their body adapts, and can take up to two years. PN is generally required if less than 50 cm of small intestine remains.

- Patients with a jejunostomy (Figure c). Fluid and electrolyte losses dominate in these patients. Adaptation does not occur. Patients with an enterocutaneous fistula will experience similar effects. In such patients:

– those with less than 100 cm of jejunum require long-term parenteral saline, with or without enteral nutrition

– those with less than 200 cm of jejunum should restrict oral hypotonic fluids and sip glucose-saline solution (sodium concentration about 100 mmol/L) to reduce stomal sodium losses.

– hypomagnesaemia is common and is treated by correcting sodium depletion or by taking oral or IV magnesium supplements

– loperamide may be used to reduce jejunal output.

Presentation in general practice

Patients with undiagnosed chronic IF may present to general practice after discharge from hospital. Those with an intact colon often present with weight loss or malnutrition but no diarrhoea, possibly weeks or even months after discharge. Often, this subgroup of patients is readmitted to hospital without IF being recognised. Chronic IF may not be identified by busy hospital teams whose focus maybe on another cause of the acute presentation.

Patients with diagnosed chronic IF may present with IF-related complications, such as line infection or PN-related liver disease. They may also present with an unrelated complaint in which complications of IF may be relevant to diagnosis or treatment, such as the absorption or metabolism of medications.

Almost invariably, patients with chronic IF have multifactorial medical problems and are often under the care of several specialists. GPs are crucial in co-ordinating specialist care, and patients will often ask their GPs’ opinion before starting interventions recommended by specialists.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of chronic IF should be considered in patients who present in the community with malnutrition in the context of previous surgical small bowel resection for any reason, or with diseases likely to affect small bowel function such as Crohn’s disease. Malnutrition may develop slowly, and some patients present to general practice months or even years after the causative event. Patients with dysmotility severe enough to cause IF may be easier to identify, although they are a heterogeneous group and the dysmotility may be intermittent or incomplete. Sometimes, patients are identified at a point of change, such as a switch in primary care provider. Children with IF may be identified by failure to thrive or to meet growth targets.

Prevalence

The availability of local resources and length of time any specialist unit has been established will likely affect the prevalence of chronic IF. Access to a local service may increase survival in patients with chronic IF, resulting in an increase in prevalence after a specialist IF unit has been established. These units may differ in their practices, such as willingness to accept terminally ill patients.

To illustrate how the presence of a specialist unit can affect the prevalence of chronic IF, currently in WA (population 2.7 million), about 35 patients with chronic IF are dependent on HPN (chronic IF prevalence, 12.9 per million). However, the FSH IF unit located in the South Metropolitan Area, WA (population 800,000), which is the longest running specialist IF unit in WA, has 25 patients (chronic IF prevalence 31.2 per million).

A 2017 Danish study estimated a point prevalence of chronic IF at about 80 per million, and a 2013 US analysis showed 79 HPN patients per million.10,11 A 2016 study from the UK reported a prevalence of those on HPN and home IV fluids as 40 per million. A more than twofold increase in period prevalence was observed from 2005 to 2015.12 Although these numbers may seem low, the impact on both the individual and the healthcare economy is high as complications are frequent and often require hospital admission.

Assessment

In patients with diagnosed IF, taking a detailed history, particularly surgical history, is essential. The length of small bowel remaining is most important (given the varying length of the small bowel the amount removed is less relevant). If the remaining small bowel length was not recorded at the time of surgery, some centres determine it radiologically, although we have not found this possible.

A nutritional assessment is necessary, and various malnutrition screening tools are available.13-15 Such patients are often managed in the inpatient setting, where detailed biochemical and haematological analysis and any necessary radiological assessment will have been carried out. If such patients are encountered in the outpatient setting, these assessments will be useful. The patient should also be assessed for treatable conditions that could be contributing to poor gut function; the list is long, but it is important to exclude infectious causes.

In both settings, a detailed assessment of nutritional input and output is necessary. Oral input and stoma or other enteral output are most useful. In general, a stoma output of more than 1500 mL per 24 hours is considered high. As a rule of thumb, a patient’s oral (or enteral) input should be more than 1000 mL higher than their enteral output to enable adequate renal perfusion and urine output.

Management

The ‘sepsis-nutrition-anatomy-plan’ approach is well established for managing patients with IF.16 Recently, the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines have modified this approach to state that the key aspects of managing IF are sepsis control, fluid and electrolyte resuscitation, optimisation of nutritional status, wound care, appropriate surgery and active rehabilitation.17 Several excellent reviews on management options in chronic IF have been published.1,9,18-23 Different approaches to management are taken: some are organised by assessment and treatment based on anatomical classification of IF, whereas others focus on management of complications.9,24 The FSH IF unit have found the 2016 ESPEN guidelines the most useful.1 These are also published as a practical guideline in a shortened form, with flow charts for easier use in clinical practice.18 An excellent review of the management of patients with high-output stoma was recently published.25

Parenteral nutrition

The defining element of management of chronic IF is parenteral support, with either IV fluid or PN. PN is a sterile solution containing varying amounts of protein, carbohydrate, fat, water, vitamins, minerals and electrolytes, depending on patients’ nutritional requirements. PN can be purchased as ready-made ‘off the shelf’ solutions containing fixed quantities of each constituent with the widest possible application, or as custom-made solutions when ready-made formulations do not meet patient requirements. There is a considerable cost difference between the two, with custom-made solutions being far more expensive.

The transition between hospital and home for patients on parenteral support can be challenging. Patients usually undergo a training period in hospital with a specialised nurse, although different countries have different systems. The FSH IF unit is increasingly trying to train patients in the home environment. Staff at the unit liaise with general practice staff prior to discharge, but patients are generally sent home with the knowledge and equipment they need to be self-sufficient. The ability to attach and detach sterile giving sets in a sterile manner is a prerequisite for home parenteral support. Although some centres insist on the patient being able to do this themselves, carers, including close relatives or live-in partners, can be trained to assist. However, the onus on these carers is high as they are essential to the patient being able to live at home.

In WA, many patients with chronic IF live outside metropolitan areas, making HPN care a challenge. However, the companies that make PN products provide an essential delivery service throughout Australia. Patients living outside a main city may depend more on their local general practice on a daily basis.

Optimisation of enteral output

After reversible causes of IF have been excluded, enteral output should be optimised. In a patient with borderline IF, this may avoid the need for parenteral support altogether, and in a patient with chronic IF, it may result in a reduced need for parenteral fluid or additional electrolytes. The following treatment strategies can be used.

- Patients with short bowel syndrome can use salt liberally, and their fluid input and output should be carefully monitored. Often, an isotonic high sodium oral rehydration solution is used. Various ‘recipes’ are available, the most popular being St Marks’ solution (www.imperial.nhs.uk/~/media/website/patient-information-leaflets/gastroenterology/st-marks-solution.pdf).18 Hypotonic oral fluid intake should be carefully monitored because, although there is a temptation among clinicians not familiar with IF to tell patients to ‘drink more fluids’, this is not always appropriate. Hypotonic oral fluid is often restricted or stopped altogether.

- Management of diet in patients with chronic IF is complex, and a dietitian is an essential member of the multidisciplinary team. Patients with short bowel syndrome are typically recommended to follow a whole-food diet and to compensate for malabsorption through hyperphagia. Nutritional recommendations, for instance the relative intake of fat and complex carbohydrate and triglycerides, vary between patients with differing residual bowel anatomy.

- H2-receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors are recommended to reduce faecal wet weight and sodium excretion, particularly in the postoperative period but also long term.18

- Antidiarrhoeal drugs are used to reduce output and are preferred over opiate drugs. Their use is generally guided by effect, but we have found that loperamide dosages of up to 40 mg a day, usually in four doses, can be effective. In patients with short bowel syndrome, loperamide capsules can be broken and the contents taken directly. We have found 30 minutes before eating to be the optimum timing.

- Although some guidelines recommend octreotide use, particularly in the short term, there are some reservations in the literature.18,26 Octreotide is not routinely used in the FSH IF unit and we have not found that it makes any difference to the need for long-term parenteral support. Its cost and the need for regular injections makes it less desirable than other therapies.

Monitoring

HPN requires close monitoring, which is crucial to minimise complications, both catheter-related and metabolic. Guidance is based mostly on expert opinion and lower-grade studies, and has been published by British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, ESPEN, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the Australasian Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. A recent review collating existing guidance into a single clear and concise review recommends checking patients' biochemical parameters at baseline and thereafter more frequently if concerns arise and less frequently when the patient’s condition is stable, as assessed by the multidisciplinary team with expertise in HPN.19

Complications of IF

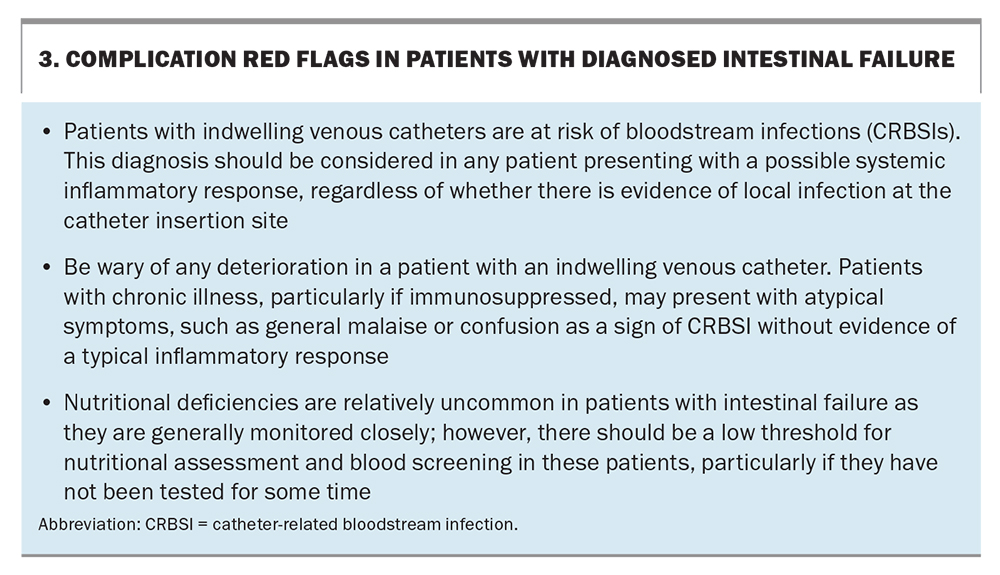

Outside the specialist centre setting, it is likely that patients will present to general practice with IF-related complications. Although not all of these complications can be managed, it is important for GPs to be aware of the likely treatments and options available to adequately advise patient. Complications are best managed in a specialty centre with an expert HPN service. Complication red flags are outlined in Box 3.

Central venous catheter-related bloodstream infection

Catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs) are the most common complication in people with diagnosed IF in the outpatient setting. CRBSIs are generally defined by clinical evidence of infection, positive blood cultures and no other proven focus of infection.1,27,28 An IF team will have prevention strategies in place for patients with long-term catheters, including dedicated patient training in line technique, either inpatient after diagnosis or in specialist centres. Single-lumen tunnelled lines or an infusaport device are preferred over peripherally inserted central catheter lines.1 Antimicrobial line locks (e.g. ethanol or taurolidine) are often used, and have been shown to reduce CRBSI rates.29,30

Patients with CRBSIs should be admitted to hospital and managed using IV antibiotics as determined by local experience. With modern antibiotic management, mortality is low, with a 2018 study reporting five deaths caused by CRBSI from 1350 infections in 715 adults.27

CVCs are retained or salvaged where possible, as repeated replacement may make future insertions more difficult. A loss of central venous access represents a common indication for referral for assessment for intestinal transplantation.6,28 Indications for acute removal of the CVC include:1,28

- signs of severe sepsis or septic shock

- ongoing clinical symptoms despite appropriate antimicrobial therapy

- metastatic (e.g. endocarditis and osteomyelitis), tunnel or fungal infections

- infection with bacteria that are highly virulent or liable to develop antibiotic resistance, such as methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

A 2015 analysis found a mean CVC salvage rate of 55.3%, although the rate varied according to infection type, with lines infected with S. aureus having a salvage rate of 42.6%. The hazard risk of a new CRBSI fell by 14% when a CVC was replaced compared with retaining the existing CVC.6 Overall salvage rates between 52% and 72.5% have been reported.4,6,7,19

Overall, line infection rates are low and it is considered good practice for IF units to monitor their infection rate. A prospective Australian study published in 2012 found one line infection for every 360 patient days and a UK retrospective study found one case per 958 patient days.31,32

Intestinal failure-associated liver disease

Between 15 and 40% of adults with chronic IF develop liver disease. Although PN is a common cause, other factors may contribute. For this reason, the term intestinal failure-associated liver disease (IFALD) is now preferred over parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease.33

Steatosis and cholestasis can occur in IFALD. Most patients are asymptomatic and general screening results show raised aminotransferase and alkaline phosphatase levels. Although uncommon, IFALD can progress to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease. IFALD is a potential indication for receiving a combined liver and small bowel transplant.34 However, life-threatening liver disease is rare and, in the 12-year history of the FSH IF unit (with 50,000 line days and 90 patients), no patients have required a combined liver and small bowel transplant.

Strategies to prevent or slow the progression of liver disease include dietetic measures, such as reducing the total energy and macronutrients in PN, cycling PN to allow for ‘days off’ rather than using it continuously every day, and preventing and promptly treating CRBSIs.33,35 There is some evidence that emulsions containing fish oil may reduce or reverse the development of IFALD in patients on PN. Most studies are in infants; however, there is increasing interest in studying this in adults.36,37

Metabolic bone disease

Metabolic bone disease describes a group of conditions commonly occurring in patients with IF.38 Bone disorders can result from malabsorption of nutrients (such as calcium and vitamin D) caused by short bowel syndrome or loss of enterocyte function, the underlying condition (e.g. Crohn’s disease) and treatment (often with corticosteroids), together with the metabolic mishandling of calcium and phosphate. About 45% of patients on HPN develop osteoporosis, typically diagnosed on bone densitometry.38

Surveillance for bone mineral density (BMD) loss is part of the current guidelines for practitioners caring for patients with IF.1 Strategies to maintain BMD include simple measures to increase vitamin D and calcium levels, and maximising vitamin K level. Current IF guidelines suggest annual dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans.1 Oral bisphosphonates are effective in patients with IF if there is sufficient enteric absorption, although intravenous preparations can also be used.39

Renal disease

Renal impairment is common in patients with IF.40,41 Uric acid and calcium oxalate renal stones are common in patients who have had an ileostomy, and their formation is likely compounded by chronic dehydration. These stones can cause renal colic, obstructive nephropathy and urinary tract infections. Nephrocalcinosis can be associated with asymptomatic progressive impairment of renal function.41 Renal function is monitored regularly in patients with chronic IF, and the presence of renal stones should be considered if deterioration occurs without obvious cause.

Evolving treatment strategies

Growth factors

Teduglutide is a relatively new treatment for patients with short bowel syndrome who are dependent on parenteral support. It is an analogue of glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2), a peptide hormone secreted in the distal small bowel. Teduglutide activates GLP-2 receptors in the gut, promoting repair and normal growth of the intestinal mucosa by increasing villus height and crypt depth. The potential of GLP-2 to improve nutritional status in patients with short bowel syndrome was first reported in the early 2000s, with two landmark randomised clinical trials published in 2011 and 2012.42-45

Teduglutide is available through the PBS for patients treated by a gastroenterologist or a specialist within a multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation unit. It is administered as a daily subcutaneous injection; studies have shown that it is generally well tolerated, and reduces the volume and number of days of parenteral support required by patients with short bowel syndrome.

Intestinal lengthening

A range of nontransplant surgical options are available for managing patients with short bowel syndrome.46 The type of surgery available depends on local expertise. Intestinal lengthening procedures include longitudinal intestinal lengthening and tailoring (Bianchi) procedure (first described in 1980) and the more recently described serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP) procedure.47,48

Intestinal transplantation

Intestinal transplantation was first performed in 1967 and, as transplant technology improved, became more common in the 1990s. Although the number of transplants increased considerably over the subsequent 20 years, current numbers have plateaued, most likely owing to the formation of specialised IF units to manage IFALD particularly.49 Because of the low number of recipients and high resources and expertise required for intestinal transplantation, relatively few centres offer this procedure. Austin Health in Melbourne is the only IF centre in Australia where it is available.

Indications for assessment for intestinal transplantation involve failure of long-term parenteral support, because of loss of venous access or recurrent unavoidable line sepsis or liver failure. One-year, five-year and 10-year graft survival has been reported as 74%, 42% and 26%, respectively, for isolated small bowel transplant; 70%, 50% and 40%, respectively, for multivisceral transplant; and 61%, 46% and 40%, respectively, for intestine and liver transplant.50

Conclusion

Long-term survival of individuals with short bowel syndrome is possible, with patients progressively able to lead almost normal lives as expertise increases and technology advances. Although patients with diagnosed IF are managed in tertiary centres, a primary physician or doctor in training is likely to come across them in the course of their everyday work. Increasing awareness across the healthcare profession that long-term PN is possible can help improve patient care is crucial. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Pironi L, Arends J, Bozzetti F, et al. ESPEN guidelines on chronic intestinal failure in adults. Clin Nutr 2016; 35: 247-307.

2. Hurt RT, Steiger E. Early history of home parenteral nutrition: from hospital to home. Nutr Clin Pract 2018; 33: 598-613.

3. Dudrick SJ. Rhoads Lecture: a 45-year obsession and passionate pursuit of optimal nutrition support: puppies, pediatrics, surgery, geriatrics, home TPN, A.S.P.E.N., et cetera. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2005; 29: 272-287.

4. Dudrick SJ, Englert DM, Van Buren CT, Rowlands BJ, MacFadyen BV. New concepts of ambulatory home hyperalimentation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1979; 3: 72-76.

5. Oke SM, Nightingale JM, Donnelly SC, et al. Outcome of adult patients receiving parenteral support at home: 36 years’ experience at a tertiary referral centre. Clin Nutr 2021; 40: 5639-5647

6. Pironi L, Arends J, Baxter J, et al. ESPEN endorsed recommendations. Definition and classification of intestinal failure in adults. Clin Nutr 2015; 34: 171-180.

7. Lal S, Teubner A, Shaffer JL. Review article: intestinal failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 24: 19-31.

8. Gardiner KR. Management of acute intestinal failure. Proc Nutr Soc 2011; 70: 321-328.

9. Nightingale J, Woodward JM, Small B; Nutrition Committee of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for management of patients with a short bowel. Gut 2006; 55 Suppl 4(Suppl 4): iv1-12.

10. Brandt CF, Hvistendahl M, Naimi RM, et al. Home Parenteral nutrition in adult patients with chronic intestinal failure: the evolution over 4 decades in a tertiary referral center. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2017; 41: 1178-1187.

11. Mundi MS, Pattinson A, McMahon MT, Davidson J, Hurt RT. Prevalence of home parenteral and enteral nutrition in the United States. Nutr Clin Pract 2017; 32: 799-805.

12. Smith TN, Naghibi M. British Artificial Nutrition Survey (BANS) Report Artificial Nutrition Support in the UK 2005–Adult Home Parenteral Nutrition & Home Intravenous Fluids. BAPEN; 2016: 1-27.

13. Ferguson M, Capra S, Bauer J, Banks M. Development of a valid and reliable malnutrition screening tool for adult acute hospital patients. Nutrition 1999; 15: 458-464.

14. Detsky AS, McLaughlin JR, Baker JP, et al. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1987; 11: 8-13.

15. Todorovic V, Russell C, Elia M (eds). The ‘MUST’ Explanatory Booklet. A Guide to the ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’ (‘MUST’) for Adults. BAPEN; UK, 2011.

16. Williams NM, Scott NA, Irving MH. Successful management of external duodenal fistula in a specialized unit. Am J Surg 1997; 173: 240-241.

17. Klek S, Forbes A, Gabe S, et al. Management of acute intestinal failure: a position paper from the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) Special Interest Group. Clin Nutr 2016; 35: 1209-1218.

18. Cuerda C, Pironi L, Arends J, et al. ESPEN practical guideline: clinical nutrition in chronic intestinal failure. Clin Nutr 2021; 40: 5196-5220.

19. Mercer-Smith GW, Kirk C, Gemmell L, Mountford C, Nightingale J, Thompson N. British Intestinal Failure Alliance (BIFA) guidance - haematological and biochemical monitoring of adult patients receiving home parenteral nutrition. Frontline Gastroenterol 2021; 12: 656-663.

20. Pironi L, Corcos O, Forbes A, et al. Intestinal failure in adults: recommendations from the ESPEN expert groups. Clin Nutr 2018; 37(6 Pt A): 1798-1809.

21. Pironi L, Sasdelli AS. Management of the patient with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and intestinal failure. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2019; 48: 513-524.

22. Nightingale JM. The medical management of intestinal failure: methods to reduce the severity. Proc Nutr Soc 2003; 62: 703-710.

23. Nightingale JM. Management of patients with a short bowel. World J Gastroenterol 2001; 7: 741-751.

24. Allan P, Lal S. Intestinal failure: a review. F1000Res 2018; 7: 85.

25. Nightingale JMD. How to manage a high-output stoma. Frontline Gastroenterol 2022; 13: 140-151.

26. Ladefoged K, Christensen KC, Hegnhoj J, Jarnum S. Effect of a long acting somatostatin analogue SMS 201-995 on jejunostomy effluents in patients with severe short bowel syndrome. Gut 1989; 30: 943-949.

27. Tribler S, Brandt CF, Fuglsang KA, et al. Catheter-related bloodstream infections in patients with intestinal failure receiving home parenteral support: risks related to a catheter-salvage strategy. Am J Clin Nutr 2018; 107: 743-753.

28. Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49: 1-45.

29. Wolf J, Shenep JL, Clifford V, Curtis N, Flynn PM. Ethanol lock therapy in pediatric hematology and oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013; 60: 18-25.

30. Liu Y, Zhang AQ, Cao L, Xia HT, Ma JJ. Taurolidine lock solutions for the prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PloS one 2013; 8: e79417.

31. Gillanders L, Angstmann K, Ball P, et al. A prospective study of catheter-related complications in HPN patients. Clin Nutr 2012; 31:30-34.

32. Green CJ, Mountford V, Hamilton H, Kettlewell MG, Travis SP. A 15-year audit of home parenteral nutrition provision at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford. QJM 2008; 101: 365-369.

33. Pironi L, Sasdelli AS. Intestinal failure-associated liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2019; 23: 279-291.

34. Carrion AF, Bhamidimarri KR. Liver transplant for cholestatic liver diseases. Clin Liver Dis 2013; 17: 3453-59.

35. Cavicchi M, Beau P, Crenn P, Degott C, Messing B. Prevalence of liver disease and contributing factors in patients receiving home parenteral nutrition for permanent intestinal failure. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132: 525-532.

36. Gura KM, Premkumar MH, Calkins KL, Puder M. Fish oil emulsion reduces Liver injury and liver transplantation in children with intestinal failure-associated liver disease: a multicenter integrated study. J Pediatr 2021; 230: 46-54 e2.

37. Park HJ, Lee S, Park CM, Yoo K, Seo JM. Reversal of intestinal failure-associated liver disease by increasing fish oil in a multi-oil intravenous lipid emulsion in adult short bowel-syndrome patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2021; 45: 204-207.

37. Allan PJ, Lal S. Metabolic bone diseases in intestinal failure. J Hum Nutr Diet 2020; 33: 423-430.

39. Pastore S, Londero M, Barbieri F, Di Leo G, Paparazzo R, Ventura A. Treatment with pamidronate for osteoporosis complicating long-term intestinal failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012; 55: 615-618.

40. Wang P, Yang J, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Gao X, Wang X. Risk factors for renal impairment in adult patients with short bowel syndrome. Front Nutr 2020; 7: 618758.

41. Nightingale JM. Hepatobiliary, renal and bone complications of intestinal failure. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2003; 17: 907-929.

42. Jeppesen PB, Hartmann B, Thulesen J, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 2 improves nutrient absorption and nutritional status in short-bowel patients with no colon. Gastroenterol 2001; 120: 806-815.

43. Jeppesen PB, Gilroy R, Pertkiewicz M, Allard JP, Messing B, O’Keefe SJ. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of teduglutide in reducing parenteral nutrition and/or intravenous fluid requirements in patients with short bowel syndrome. Gut 2011; 60: 902-914.

44. Jeppesen PB, Pertkiewicz M, Messing B, et al. Teduglutide reduces need for parenteral support among patients with short bowel syndrome with intestinal failure. Gastroenterol 2012; 143: 1473-181 e3.

45. Buchman AL. Teduglutide and short bowel syndrome: every night without parenteral fluids is a good night. Gastroenterol 2012; 143: 1416-1420.

46. Sommovilla J, Warner BW. Surgical options to enhance intestinal function in patients with short bowel syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr 2014; 26: 350-355.

47. Bianchi A. Intestinal loop lengthening--a technique for increasing small intestinal length. J Pediatr Surg 1980; 15: 1451-51.

48. Kim HB, Fauza D, Garza J, Oh JT, Nurko S, Jaksic T. Serial transverse enteroplasty (STEP): a novel bowel lengthening procedure. J Pediatr Surg 2003; 38: 425-429.

49. Loo L, Vrakas G, Reddy S, Allan P. Intestinal transplantation: a review. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2017; 33: 203-211.

50. Cai J, Wu G, Qing A, Everly M, Cheng E, Terasaki P. Organ procurement and transplantation network/scientific registry of transplant recipients 2014 data report: intestine. Clin Transpl 2014: 33-47.