Atrial fibrillation management. The central role of the GP

Opportunistic annual screening for atrial fibrillation (AF) is strongly recommended in those aged 65 years and over and is easily accomplished. Integrated care to support comprehensive treatment and address the specific needs of people with AF is required, and GPs are central to its effective delivery.

Update

An updated version of Table 2 in this article is available here.

- Opportunistic screening for atrial fibrillation (AF) in the clinic or community is recommended for all patients aged over 65 years.

- Deciding between a rate and rhythm control strategy at the time of diagnosis of AF and periodically thereafter is important.

- Beta-blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists (e.g. diltiazem, verapamil) remain the first-line choice for acute and chronic rate control.

- When pharmacologic rhythm control is the selected strategy, flecainide is preferable to amiodarone for both acute and chronic rhythm control provided left ventricular function is normal and patient does not have coronary disease.

- Failure of rate or rhythm control should prompt consideration of percutaneous or surgical ablation.

- The sexless CHA2DS2-VA assessment, which standardises thresholds across men and women, is recommended to assess stroke risk.

- Anticoagulation is recommended for a CHA2DS2-VA score of 2 or more.

- When anticoagulation is indicated, nonvitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) are recommended in preference to warfarin.

- Net clinical benefit almost always favours stroke prevention over major bleeding, so bleeding risk scores should not be used to avoid anticoagulation in patients with AF.

- An integrated care approach using patient education and available e-health tools and resources should be delivered by a multidisciplinary team.

- Regular monitoring and feedback of risk-factor control helps to ensure treatment adherence and persistence.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common recurrent arrhythmia faced in clinical practice, and it causes substantial morbidity and mortality.1-3 In Australia, prevalent AF cases in people aged 55 years or more are projected to double over the next two decades as a result of an ageing population and improved survival from contributory diseases.4 Recent Australian data show that hospitalisations of patients with AF increased 295% over a 21-year period – a higher increase than for myocardial infarction or heart failure over the same period.5

In many patients, AF progresses from short paroxysmal episodes to more frequent and persistent attacks, and then often to permanent AF. However, progression can be mitigated by aggressive targeting of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors.6

AF is independently associated with an increased long-term risk of stroke, heart failure and all-cause death.1-3 The risk of dying from stroke can be reduced by administration of oral anticoagulants (OACs), but all-cause mortality and deaths from complications such as heart failure remain high, despite guideline-adherent treatment.1,7 This highlights the need for a comprehensive care approach to reduce overall mortality in AF-affected patients.8

The National Heart Foundation of Australia and Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand recently produced guidelines on the diagnosis and management of AF.9 These are intended to be used by practising clinicians across all disciplines caring for such patients. This review covers the sections of the guidelines that are particularly relevant to GPs.

What defines atrial fibrillation?

The diagnosis of AF requires rhythm documentation using an ECG. If AF is present, there are irregular RR intervals and no discernible P waves. By accepted convention, an episode lasting at least 30 seconds is diagnostic. Nonvalvular AF (NVAF) refers to AF in the absence of moderate to severe mitral stenosis or a mechanical heart valve.10

Screening for atrial fibrillation

There is strong epidemiological evidence that previously unknown AF is associated with about 10% of all ischaemic strokes.11,12 Evidence from systematic reviews indicates that 1.4% of patients in community or practice situations aged 65 years or over will have unknown asymptomatic AF on single time-point screening of pulse ECG.13

Opportunistic annual screening for AF in general practice in patients aged 65 years or over is strongly recommended, and is easily accomplished by pulse palpation followed by an ECG (if irregular), or by an ECG rhythm strip using a handheld ECG. This screening can be incorporated into standard consultations or undertaken by practice nurses during chronic care consultations or immunisations. Devices that provide a medical quality ECG trace are preferred to pulse-taking or pulse-based devices for screening, because an ECG is required to confirm the diagnosis.

Newer devices such as the Apple watch are able to detect AF, but there is limited published evidence to date to justify routine screening with these devices. Patients presenting to the GP with arrhythmia detected on an Apple watch should have a 12-lead ECG to confirm the diagnosis.

Diagnostic work up

A 12-lead ECG not only establishes the diagnosis of AF, it also provides evidence of conduction defects, ischaemia and signs of structural heart disease. A diagnostic work up should also include serum electrolyte levels, as abnormal concentrations may result in muscle contraction disorders, other cardiac arrhythmias and drug interactions.

Symptomatic thyroid disease appears to be rare in people presenting with AF, and yield of testing is low.14 Making a diagnosis of overt thyroid disease is also complicated by the fact that any acute illness affects thyroid indices;15 hence, this screening should be reserved for stable outpatients, highlighting the important role of the GP.

A transthoracic echocardiogram can help in patient management by identifying valvular heart disease, quantifying left ventricular (LV) function and atrial size, and should be performed in all patients with newly diagnosed AF.

Detection and management of risk factors and concomitant diseases

Cardiovascular risk factors are recognised contributors to the development of AF.16 Several of these risk factors are well established; they include hypertension, diabetes mellitus and alcohol excess. In addition, several cardiovascular conditions are associated with the development of AF, including coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular disease and sinus node disease.

With the burden of AF increasing at rates greater than those predicted by known risk factors, there has been interest in several newer risk factors, including obesity, sleep apnoea, physical inactivity and prehypertension.17-22

The more risk factors that an individual has, the greater the likelihood that a person will develop AF and more persistent AF.23,24 Traditional cardiovascular risk factors are also an important determinant of recurrence of AF when using a rhythm-control strategy.25-30

Treating underlying risk factors has been observed to reduce incident AF and the risk of complications associated with AF; hence, their management is an important part of managing patients with AF.31,32

Recent Australian studies have shown that physician-led intervention of risk factor management in overweight and obese patients led to a marked reduction in AF symptoms, episode frequency and duration.33 The response is graded – the greater the impact on the risk factor, the more likely that sinus rhythm will be maintained.34,35

Arrhythmia management

Rate vs rhythm control

In all patients with new onset AF, a decision regarding rate versus rhythm control is required (Box). A rate-control strategy may be used in preference to rhythm control in patients with minimal symptoms or in those in whom attempts at maintaining sinus rhythm are likely to be futile. Patients who have not responded to a rhythm-control strategy may be managed with rate control.

Strategies for rate control

First-line options for rate control are beta-adrenoceptor antagonists and nondihydropyridine calcium channel antagonists (diltiazem or verapamil), alone or in combination (Flowchart 1).36 Digoxin continues to have a role as a second-line agent, but there are risks of toxicity. Amiodarone should be considered a last-line option, given its toxicity profile. Membrane-active rhythm-control agents (e.g. flecainide or sotalol) should not be used as part of a rate control strategy.

Strategies for rhythm control

Patients with haemodynamic instability require urgent electrical cardioversion. In stable patients, acute rhythm rather than rate control can be considered if symptoms are unacceptable, or in patients experiencing their first episode of AF. There is a high spontaneous reversion rate to sinus rhythm for new onset AF within 48 hours, so although pharmacological cardioversion can be considered, a ‘wait and watch’ approach with rate control may be reasonable in a mildly symptomatic patient.

Once patients have reverted, the choice of long-term antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) therapy depends on the patient’s comorbidities and preferences. Options include flecainide, amiodarone or sotalol, generally informed by cardiologist advice. For further information see the full guidelines at www.heartfoundation.org.au/for-professionals/clinical-information/atrial-fibrillation.37 Adjunctive lifestyle modification and strict cardiovascular risk-factor control should not be overlooked in rhythm-control management of AF.33,34

AF ablation is an effective procedure for appropriately selected patients with symptomatic AF. It is applicable to patients who have failed or are intolerant to AADs, or for some patients who decline AAD treatment. Multiple randomised controlled trials have demonstrated higher rates of sinus rhythm maintenance compared with AADs.38 Although the evidence is strongest for percutaneous treatment, surgical ablation may also be offered under certain circumstances.

Stroke prevention

Prediction of stroke risk and use of anticoagulation therapy

The Australian guidelines recommend using a CHA2DS2-VA score to assess stroke risk in patients with nonvalvular AF (Table 1). This is recommended in preference to the CHA2DS2-VASc score as it provides one consistent anticoagulation threshold recommendation for both sexes. The female sex category (Sc) is no longer required as it adds little predictive value in the absence of additional risk factors.39-41

Stroke risk factors may change over time because of ageing or development of new comorbidities. Hence, annual review of low-risk patients is recommended to ensure that risk is adequately characterised to guide OAC therapy.

For a CHA2DS2-VA score of 2 or more, the benefits of reduced stroke and reduced mortality from anticoagulation certainly outweigh the risk of major haemorrhage, and treatment with an OAC is recommended. At a CHA2DS2-VA score of 1, the risk-benefit equation is more balanced, so other factors require greater consideration in the decision on anticoagulation. Oral anticoagulation therapy to prevent thromboembolism and systemic embolism is not recommended in patients with NVAF whose CHA2DS2-VA score is 0 (Flowchart 2).

Anticoagulation with warfarin reduces the risk of embolic stroke by 64% and of mortality by 26% when used in patients with NVAF.42 However, warfarin is difficult to use in clinical practice because of multiple food and drug interactions, and the need for frequent monitoring to keep the anticoagulation within the therapeutic range.43,44 As with all forms of antithrombotic or anticoagulant therapy, bleeding is increased with warfarin, but the rate of intracranial haemorrhage is higher compared with other agents.45-47 Therefore, when oral anticoagulation is initiated in a patient with NVAF, a nonvitamin K oral anticoagulant (NOAC) – apixaban, dabigatran or rivaroxaban – is recommended in preference to warfarin. There is no role for NOACs in patients with valvular AF (mechanical heart valves or moderate to severe mitral stenosis) and warfarin remains the recommended treatment option.

The evidence for stroke prevention with aspirin is weak and aspirin is associated with a risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.45,48 Aspirin together with clopidogrel was 44% less effective than warfarin in stroke prevention, with comparable incidence of major bleeding.49 Antiplatelet therapy is therefore not recommended for stroke prevention in patients with NVAF, regardless of stroke risk.

Minimisation of bleeding risk

The risk of bleeding with warfarin is 1.3% per year in patients with an international normalised ratio (INR) of 2.0 to 3.0, and NOACs have either a comparable or a slightly reduced major bleeding risk relative to warfarin.50,51 Bleeding risk can be estimated by a variety of clinical scores, although the predictive power for all of them is modest. The net clinical benefit almost always favours stroke prevention over major bleeding, so bleeding risk scores should not be used to avoid anticoagulation in patients with AF. Higher scores might be used to alert the clinician to a greater need to attend to any modifiable bleeding risk factors.

Modifiable bleeding risk factors include hypertension, falls and peptic ulceration. The risk associated with recurrent falls may be reduced by falls prevention programs. In people with recurrent falls despite efforts to decrease risk of falling, a more detailed discussion may need to be had on the risks associated with continuing anticoagulation versus the risks associated with stopping anticoagulation.

Most significant bleeds occur from the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). Causes of previous upper GIT bleeding in this context, such as peptic ulceration, are usually preventable and are not a contraindication.52 Untreatable or difficult-to-prevent causes of lower GIT bleeding (e.g. recurrent bleeding from angiodysplasia) may be a contraindication to anticoagulation.

Major bleeding can be reduced through high-quality INR control with warfarin therapy, and appropriate selection of NOAC dosage according to age and renal function (Table 2).52-54

Combining anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents

Recent guidelines based predominantly on consensus opinion have supported the use of combined anticoagulant and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients who require OAC for stroke prevention, and DAPT following acute coronary syndrome or stent implantation, or both. Discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy should be considered 12 months after stent implantation, acute coronary syndrome or both, with continuation of OAC alone. The selection of therapy is complex and typically based on advice from a cardiologist. For further information see the full guideline.37

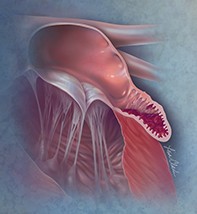

Stroke prevention with left atrial appendage occlusion

Percutaneous or surgical left atrial appendage occlusion may be considered for stroke prevention in patients with NVAF at moderate to high risk of stroke and with contraindications to oral anticoagulation therapy.

Medication adherence and persistence with atrial fibrillation pharmacotherapy

One of the most sobering statistics regarding AF is that about one-third to half of patients discontinue therapy within two to two-and-a-half years of initiation.55,56 For this reason, a major role for the GP is regular monitoring and support of patient treatment adherence and persistence.

Among the broader non-AF literature, meta-analyses have shown that medication adherence interventions can lead to significant, albeit modest, improvements in patient-centred outcomes. Unfortunately, the most effective interventions are usually complex (comprising tailored ongoing support, cognitive behavioural therapy, motivational interviewing, education or daily treatment support; which are delivered face-to-face, often via pharmacists) and may be difficult to implement in real-world practice.

Resources for GPs

Existing resources are available to support GPs in providing integrated care, including:

- access to multidisciplinary expertise (e.g. allied health services, nurse practitioners, accredited pharmacists) via Medicare-funded care plan referrals, multidisciplinary case conferences, medication management reviews, and health assessments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and older people

- initiatives to support the adoption of ehealth in general practice (e.g. the Medicare-funded Practice Incentives Program eHealth incentive).

- training resources to support health professionals in effectively and efficiently improving medication adherence.57 A range of additional Australian resources may be obtained from the Heart Foundation, the National Stroke Foundation, and the National Prescribing Service (NPS) MedicineWise.

Conclusion

The rapidly increasing prevalence of AF has placed a significant burden on healthcare use in Australia, challenging the delivery of health services and resulting in care that is consequently more fragmented. There is a clear need for more integrated care to support the comprehensive treatment required, and to address the specific needs of people with AF. Given the high population prevalence of AF and that it most often occurs in the context of multimorbidity, there is a need for GPs to have a major role in the care of patients with AF. MT