Intertriginous skin disorders: what’s lurking where?

Although intertriginous skin disorders are generally benign, some can impair quality of life or be life threatening. A careful history and clinical examination can diagnose the majority of these disorders; however, in flexural locations, friction and maceration can alter their characteristic appearance. Most intertriginous skin disorders can be successfully managed in the primary care setting, with certain cases referred for specialist opinion.

- Most intertriginous skin disorders can be successfully diagnosed and managed in the primary care setting.

- The majority of intertriginous skin disorders can be diagnosed primarily on the basis of a careful history and examination. Lesion morphology is a very important diagnostic aid.

- Examination of non-intertriginous sites (including the nails) may reveal useful diagnostic features.

- Failed response to adequate treatment should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis.

- Dermatologistreferralisindicatedforapatientwiththe suspected first presentation of a genetic disorder, an urgent condition, severe or treatment-recalcitrant disease, or uncertain diagnosis. Emergency department referral is required for a patient who is systemically unwell.

Intertriginous skin disorders are common presentations in general practice. They encompass a wide variety of infectious, inflammatory, genetic and neoplastic processes, which range from benign self-limiting conditions to chronic diseases that can impair quality of life or be life threatening.1 Flexural skin is intrinsically prone to friction, which can lead to superimposed infections, highly variable clinical features and diagnostic difficulties. With a structured approach, most cases can be successfully diagnosed and managed in primary care, while certain cases should be referred for specialist opinion. This article discusses the diagnosis and management of skin disorders that occur in intertriginous areas, with or without skin involvement elsewhere.

What constitutes intertriginous skin?

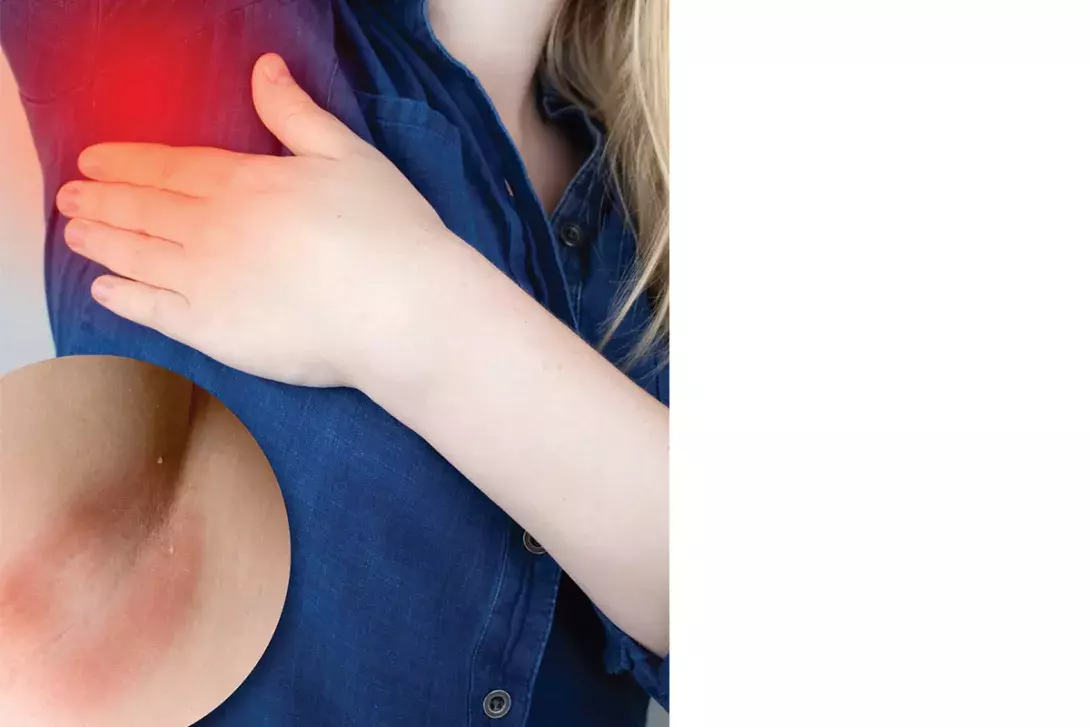

Intertriginous areas are sites in which opposing skin surfaces come into contact and result in chronic skin occlusion. The main intertriginous skin areas are the groin folds, axillae and natal cleft. Body habitus may create additional intertriginous sites, such as inframammary and abdominal skin folds.

Diagnosis

Most intertriginous skin disorders can be diagnosed primarily on the basis of a careful history and examination, with the list of potential diagnoses usually able to be narrowed on the basis of clinical features. Key features of the most common intertriginous skin disorders in adults are summarised in Box 1.

History

A thorough history provides useful diagnostic information, with the patient’s age and the duration and clinical course of the condition being key components. Some intertriginous skin conditions are more commonly seen in the paediatric population, such as bullous impetigo, cutaneous candidiasis, seborrhoeic dermatitis, viral warts and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.2-4 A genetic condition will first present at birth or in childhood. Acute onset suggests a primary infective process or drug eruption. A chronic, relapsing course may suggest a chronic inflammatory disorder such as psoriasis (Figure 1) or hidradenitis suppurativa (Figure 2).5

Associated signs and symptoms should be noted. Pain and itch tend to be common features of intertriginous skin conditions. Classic painful disorders include furuncles, hidradenitis suppurativa, metastatic Crohn’s disease, Hailey-Hailey disease and pemphigus vegetans.6-8 Itch is frequently seen with scabies, dermatitis, tinea cruris, cutaneous candidiasis, extramammary Paget’s disease, granular parakeratosis (Figure 3) and Fox-Fordyce disease.9-11 In Dowling-Degos disease, freckle-like pigmentation is often seen.12 Pseudoxanthoma elasticum may present with peripheral circulatory and upper gastrointestinal symptoms, and angioid streaks may be seen on retinal examination.13

A number of systemic diseases are associated with intertriginous skin disorders. People who have diabetes mellitus are more likely to develop cutaneous candidiasis, acanthosis nigricans (Figure 4), erythrasma (Figure 5) and acrochordons than people who do not have diabetes.14 Patients with HIV infection are more likely to develop seborrhoeic dermatitis, especially in a generalised distribution.15 Extramammary Paget’s disease is sometimes associated with an underlying internal malignancy.9

Reviewing a patient’s current and (recent) past medications is important to identify or exclude an allergic drug eruption or immunosuppressant-associated infective dermatoses.16 For certain conditions, such as contact dermatitis, identification, cessation and avoidance of a culprit agent is essential for management; therefore, taking a thorough history to identify exposure to potential skin irritants or allergens is essential, such as new soaps, topical creams, laundry detergents and rinses, as well as occupational substances. The allergic type of contact dermatitis is not as common as the irritant type. Infectious contacts should be noted, as patients with scabies, tinea, impetigo or boils may report family members or household contacts having similar skin symptoms.

A family history may provide important clues to the diagnosis, as conditions such as psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa, Hailey-Hailey disease (Figure 6), Dowling-Degos disease and pseudoxanthoma elasticum often run in families.7,12,13

Examination

Assessment of lesion morphology and distribution are key components of the clinical examination, with morphological features being possibly the single most important aid to diagnosis (Table 1). The distribution of the rash may provide further clues. Infective and malignant processes are typically unilateral and involve only a single or limited number of areas, whereas genetic and inflammatory disorders are usually symmetrical and affect multiple areas.

Intertriginous rashes commonly involve non-intertriginous skin, so an examination of the whole body can provide useful diagnostic information. Psoriasis commonly affects the scalp, natal cleft and extensor limbs. Seborrhoeic dermatitis often involves the scalp, nasolabial folds and eyebrows. The violaceous papules of lichen planus are usually seen on the flexor wrists and ankles.17 Scabies typically affects the finger web spaces, flexor wrists, periareolar skin and male genitalia. Pseudoxanthoma elasticum is most commonly seen on the neck.13 A herald patch may be observed in pityriasis rosea. Bacterial folliculitis is often limited to hair-bearing areas. Ensuring adequate examination of sites such as inframammary areas and abdominal folds, as well as the contralateral site, should be a part of a complete assessment.

The patient’s nails should also be examined. Nail changes such as discolouration, hyperkeratosis and onycholysis may accompany tinea corporis or tinea cruris. Common nail changes in psoriasis include oil drop appearance, onycholysis, pitting and subungual hyperkeratosis. Lichen planus may be associated with nail ridging and onycholysis. Longitudinal leukonychia occurs in around 70% of patients with Hailey-Hailey disease.7

Simple office tests can provide useful information. For example, dermoscopy can aid in the visualisation of burrows as well as the highly characteristic ‘delta wing’ sign (arrowhead shape that represents the head of the mite and its burrows) in the diagnosis of scabies. Wood’s lamp examination may be useful to confirm erythrasma, with coral pink fluorescence being characteristic.

Investigations

After a careful history is taken and physical examination conducted, additional testing may be required if the diagnosis remains uncertain or if there is a need to confirm a preliminary diagnosis. For example, skin scrapings for microscopy and culture may be needed to confirm a diagnosis of scabies or exclude fungal infection in undifferentiated conditions with scale. Bacterial microscopy, culture and sensitivity testing may be needed for pustular or blistering lesions. Direct immunofluorescence testing can be useful for suspected autoimmune blistering diseases.

Skin biopsies are not usually needed and are reserved for patients with an uncertain diagnosis, such as those with an atypical presentation, or for situations where earlier investigations have not yielded sufficient information or histopathological examination is required to confirm a diagnosis.

Management

Management of most intertriginous skin disorders can be initiated in primary care, with the approach depending on the extent and severity of disease (Table 2). Failed response to adequate treatment should prompt reconsideration of the diagnosis.

It can be helpful to ask whether a patient has tried any therapies prior to presentation, as this can guide management. Preparations that patients may have tried include over the counter topical zinc oxide preparations and antifungal creams.

Referral

Referral to a dermatologist is warranted for a patient with an uncertain diagnosis, disease that is severe or recalcitrant to treatment, a suspected first presentation of a genetic disorder or an urgent condition (Box 2).18-20 A lower threshold for referral should be exercised for children. A patient who is systemically unwell requires emergency department referral.

Conclusion

Intertriginous skin disorders are mostly benign but, rarely, can represent life-threatening disease. They may be difficult to diagnose because friction and maceration can alter their characteristic appearance, but the majority of cases can be diagnosed primarily on the basis of a careful history and examination. Lesion morphology is possibly the single most important diagnostic aid. Most intertriginous skin disorders can be successfully diagnosed and managed in the primary care setting, with certain cases referred for specialist opinion. MT