Laryngopharyngeal reflux and reflux cough: a diagnostic conundrum

Laryngopharyngeal reflux or ‘atypical reflux disease’ is an important and under-recognised diagnosis, often resulting in numerous visits to GPs with low-yield investigations and referrals to a variety of specialists, including respiratory physicians, ENT surgeons and gastroenterologists. This is frequently at considerable expense to the patient. Pathophysiological factors leading to the extraoesophageal symptoms of atypical reflux disease are poorly understood and acid suppression treatment is largely ineffective, leading to frustration on the part of the patient and their GP.

- Laryngopharyngeal symptoms have a plethora of potential causes, so the attribution of aetiology and selection of appropriate management is challenging and complex.

- ‘Silent reflux’ has largely been immeasurable, so the diagnosis of atypical reflux disease remains uncertain and underestimated. Evidence in this area is lacking and requires more research.

- Standard treatments for typical reflux disease are usually ineffective in the management of laryngopharyngeal reflux and reflux cough. A combination of alginate, a reduction in the size of meals consumed, the adoption of a raised sleeping position and the prescription of prokinetic therapy can be useful in some patients as a six-week trial.

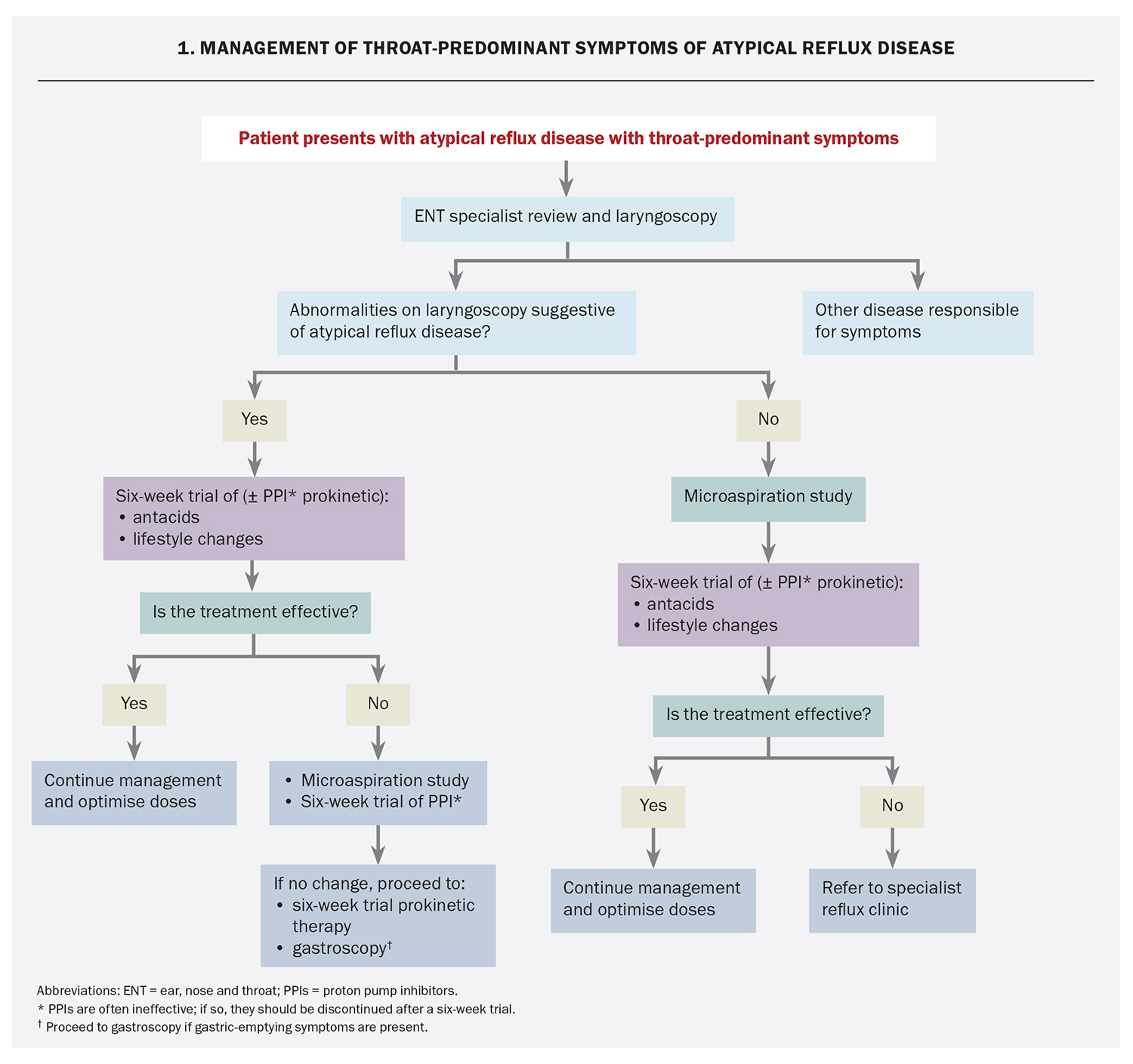

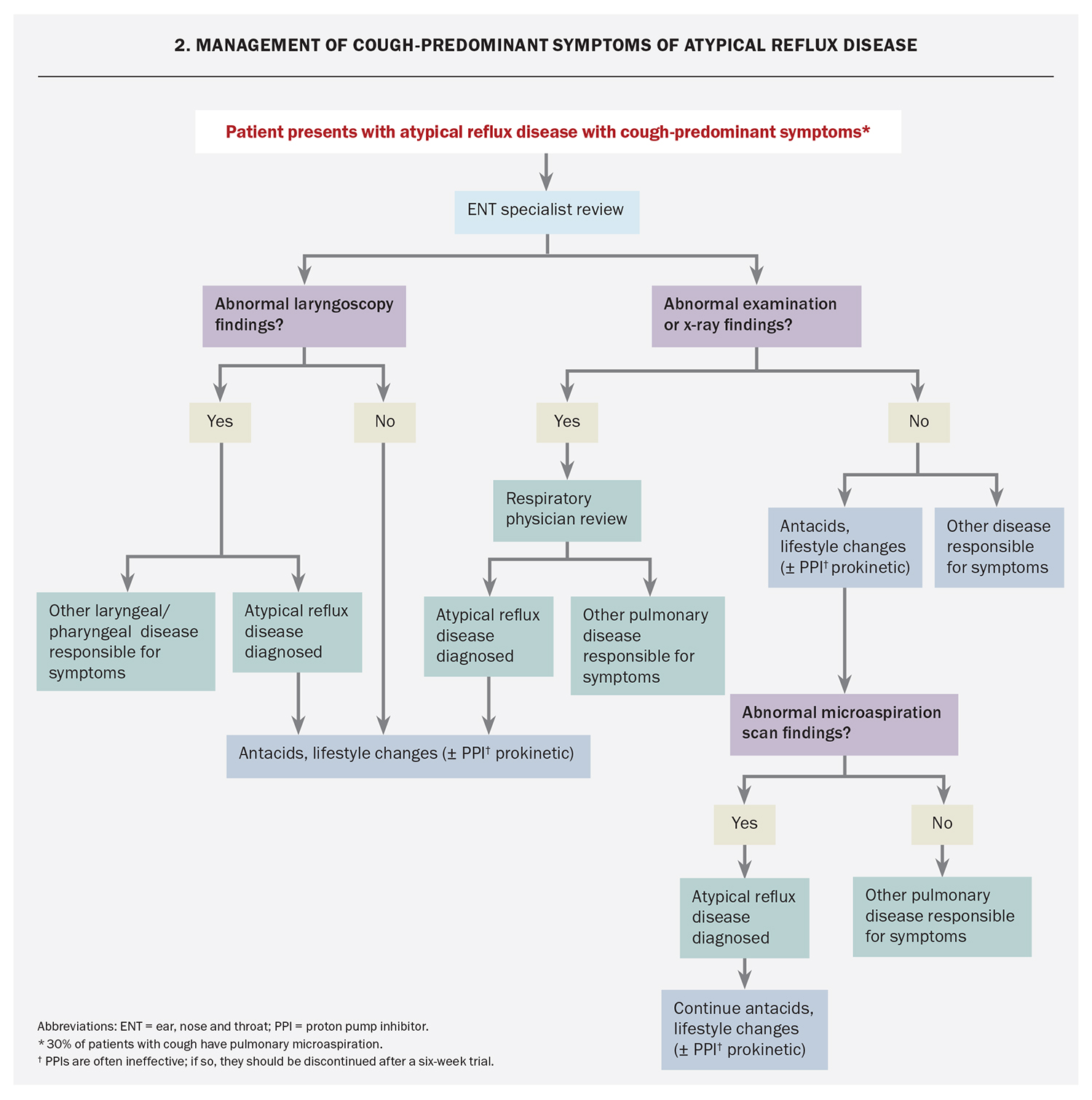

- Specialist referral is usually indicated and can be informed by whether the patient’s symptoms are classified as throat-predominant or cough-predominant in nature.

Laryngopharyngeal reflux and reflux cough are recognised as a symptomatic variation of the same physiological process of gastro-oesophageal regurgitation (i.e. atypical reflux). Atypical reflux disease is a significant problem, with an estimated 5 to 8% of the Caucasian population of the USA burdened with chronic unresolved cough, likely representing symptomatic disease.1 It can be speculated that insensible pulmonary inhalation secondary to microaspiration contributes towards an unknown proportion of lung disease, which might have otherwise been prevented with adequate recognition and management of atypical reflux disease. This article provides specialist insight into the diagnosis and management of atypical reflux disease.

Pathogenesis

Until recently, there has been a poor understanding of physiological factors leading to atypical reflux symptoms and conclusive evidence in this area is lacking. Historically, the features of atypical reflux disease have been considered similar to those of typical reflux, including exposure of the oesophagus to high levels of acid, a strong association with the presence of hiatus hernia and dysfunction of the antireflux mechanism in the lower oesophageal sphincter.

Compared with typical reflux, atypical reflux disease appears to be more closely related to motility phenomena, as evidenced in its associations with dysphagia, irritable bowel syndrome and gastrointestinal dysmotility.2,3

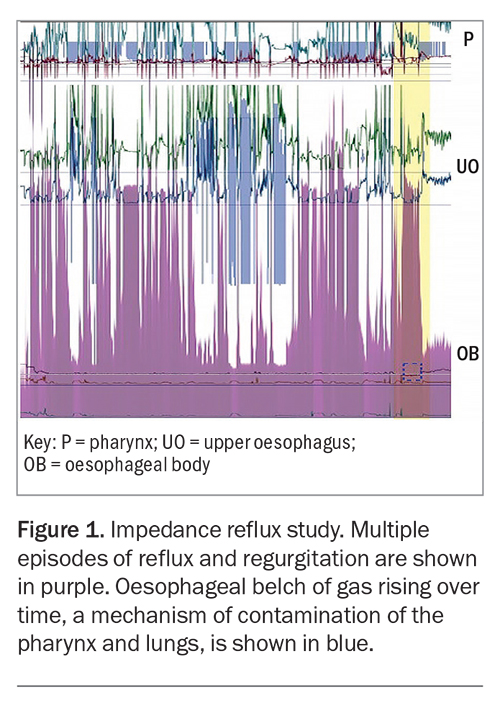

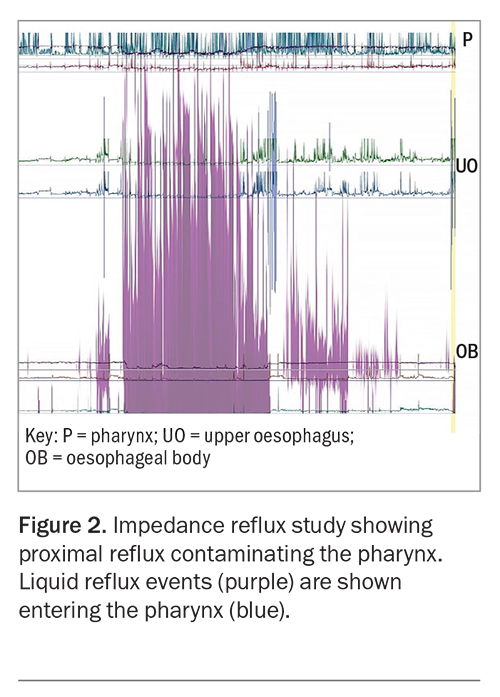

Its pathophysiology is a different process from typical reflux disease, which causes symptoms of heartburn. In atypical reflux, the reflux events are likely due to droplet regurgitation, which contaminates the posterior larynx, pharynx and extraoesophageal space. These regurgitation events can be preceded by subclinical gaseous reflux, which may explain how proximal contamination in atypical reflux disease travels further than the liquid regurgitation events of typical reflux disease (Figure 1). These proximal regurgitation events are frequently shown to occur without the patient’s awareness (i.e. ‘silent’) (Figure 2).

It is poorly understood that reflux events are largely nonacidic in the pharynx and there is substantial discord in the literature surrounding atypical reflux disease; the accuracy of various modalities of pharyngeal measurement is of particular concern. Physiological studies (see below) have demonstrated that regurgitation of gastric contents is neutralised by the alkaline saliva of the oesophageal lumen. Frequently, the same studies have demonstrated that the regurgitated contents can enter the hypopharynx in symptomatic patients.4-6

Further to hypopharynx aspiration, pulmonary microaspiration has been associated with the development of recurrent chest infections, pneumonia, bronchiectasis, inflammatory pulmonary fibrosis and, possibly, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung transplant rejection.7 The term ‘airway reflux disease’ refers to such complications.8

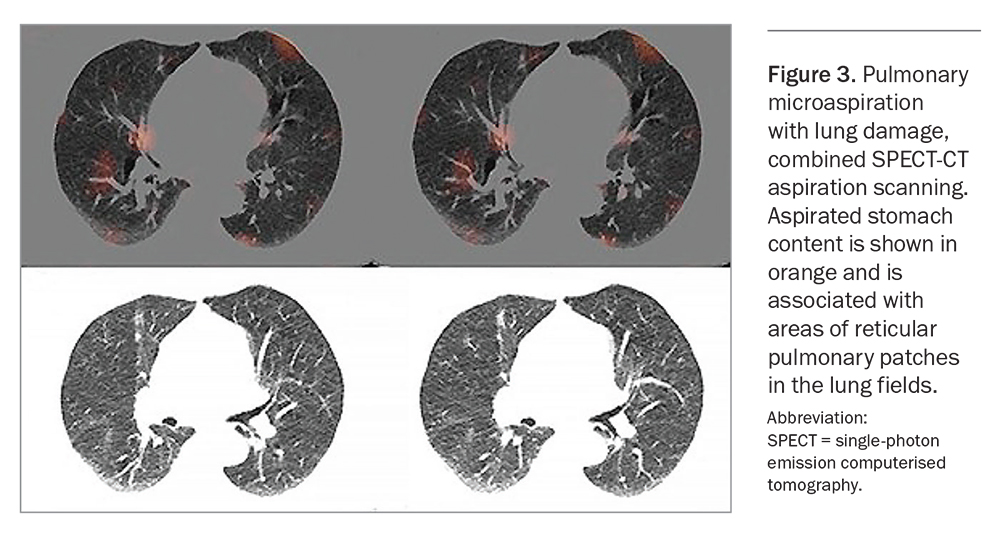

Hypersensitivity, secondary to chronic irritation of the pharynx, larynx or lung, is the likely mechanism for the respiratory symptoms of atypical reflux. Stimulation of the inflammatory cascade via the interleukin pathway occurs in the lungs as a result of aspiration of pancreatic and biliary enzymes, bacteria and other components of gastric fluid (not simply acid). This has been demonstrated by specialised microaspiration nuclear medicine scanning in patients with atypical reflux disease (Figure 3).

Despite the difference in pathophysiology, the features of atypical reflux are consistent with definitions for ‘reflux disease’ as outlined by the Montreal consensus, in which symptoms are caused by gastric fluid in either the oesophagus or the extra-oesophageal spaces.9

Symptoms

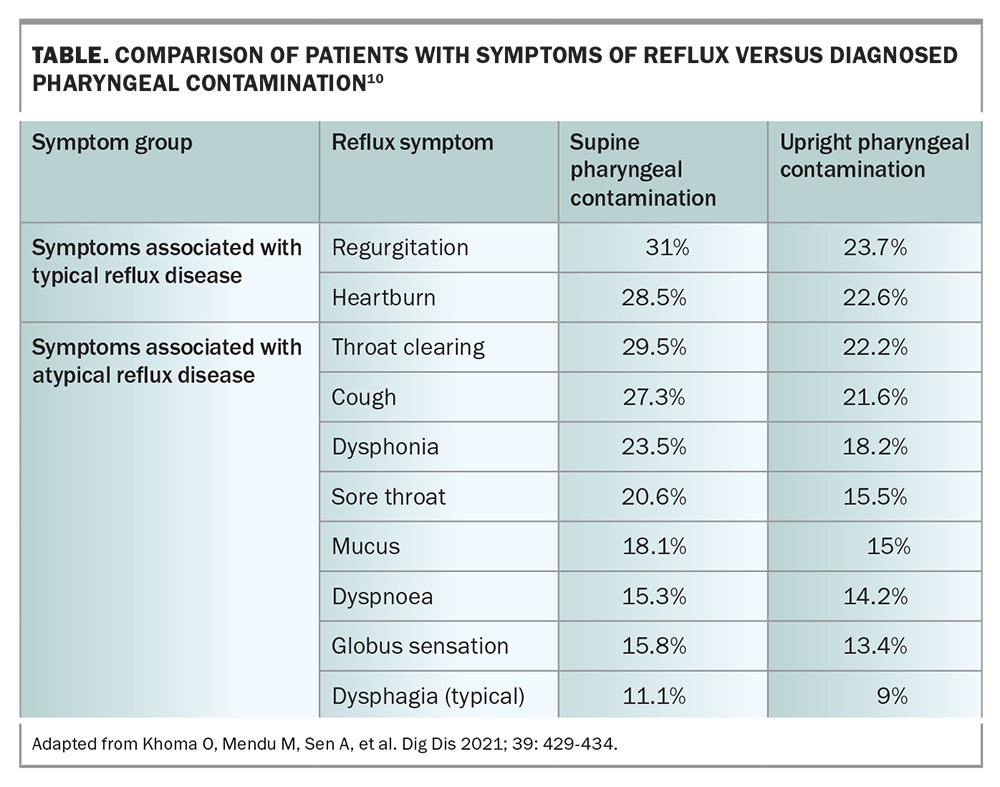

Symptoms of atypical reflux include a dry chronic cough with several precipitating factors, including the patient bending over or lying supine at night. Symptoms are often exacerbated in the postprandial period or first thing in the morning, with improvement over the course of the day. Associated symptoms include: globus pharyngeus (the sensation of a lump or foreign body in the throat with a tightening or choking feeling); overabundance of mucus in the throat; persistent throat clearing; dysphagia; pain in the throat; and dysphonia, which is a concerning feature requiring visual inspection of the larynx, especially in patients who smoke (Table).

Atypical reflux disease is associated with irritable bowel syndrome and motility-related dysphagia.3,10 Recent studies have demonstrated on multivariate analysis that nonspecific oesophageal dysmotility is the strongest predictor of pharyngeal contamination by reflux fluid.10

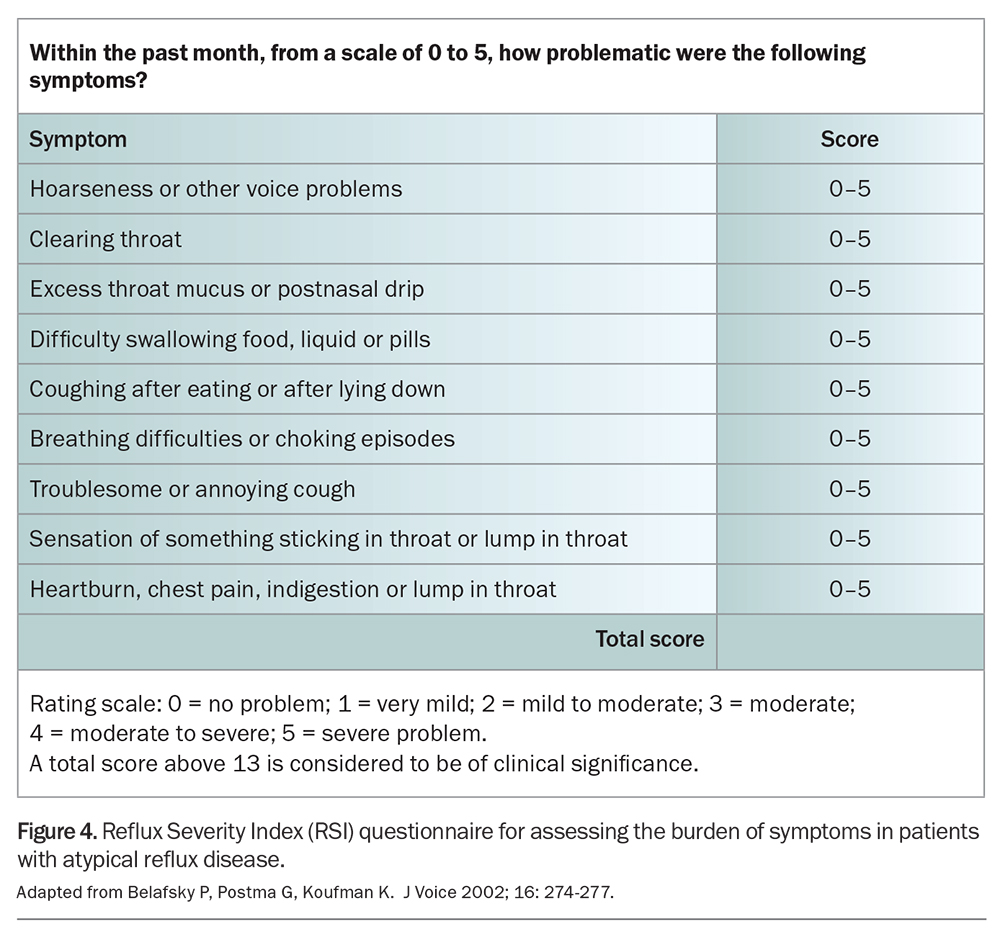

The Belafsky symptom scoring system for atypical reflux disease was initially thought to be diagnostically useful. However, recent studies have demonstrated the poor sensitivity of the scoring system. It is not an adequate diagnostic tool, but may be useful in assessing a patient’s response to treatment (Figure 4).11,12

Confounding factors and clinical traps

Misinterpretation and subjectivity can confound self-administered symptomatic questionnaires and may help to explain the lack of reliable data on atypical reflux disease. To avoid such traps and pitfalls in a patient’s disclosure of reflux symptoms, clinicians should be careful in ensuring a precise history is taken.

A patient’s description of ‘heartburn’ may describe a burning sensation or pain in the throat and may not be the retrosternal sensation attributed to typical reflux disease, or vice versa. Patients may also have difficulty differentiating the source of mucus in the back of the throat as postnasal drip or regurgitation and may consider such a substance as ‘bile’ instead of mucus. ‘Reflux’ to some patients can mean a bad taste in the mouth, bad breath or a burning tongue.

A particular challenge occurs in patients with typical reflux disease on acid suppression therapy who no longer feel retrosternal burning, but experience atypical reflux symptoms through insensible regurgitation into the pharynx. Such patients are often misdiagnosed with atypical reflux disease, rather than with a severe form of typical reflux disease with proximal oesophageal ‘flooding’. Large inhalation events are a significant concern and, without specific questioning, patients are unlikely to disclose previous episodes of choking or laryngospasm (usually occurring at night and after large meals). These patients should be managed as for typical reflux disease, with specialist referral if indicated.

Differential diagnosis and investigation

The diagnosis of typical or atypical reflux disease is challenging and depends on the exclusion of other differentials through investigation and specialist referral. Many patients with atypical reflux disease can have cough-predominant symptoms (‘reflux cough’) and are frequently referred for specialist respiratory assessment and investigation, such as pulmonary function testing, asthma provocation studies, high-resolution CT chest and bronchoscopy. The European Respiratory Society recommends history-taking, physical examination and chest x-ray for the evaluation of cough symptoms.13,14

Diagnoses for exclusion include taking ACE inhibitors, having asthma, smoking and occupational exposure. There may be partial response to bronchodilator inhalers, as microaspiration can result in hypersensitivity-induced bronchospasm. ‘Reflux cough’ should be suspected in patients with so-called late-onset asthma, cough-predominant asthma, atypical asthma and atypical pneumonia.

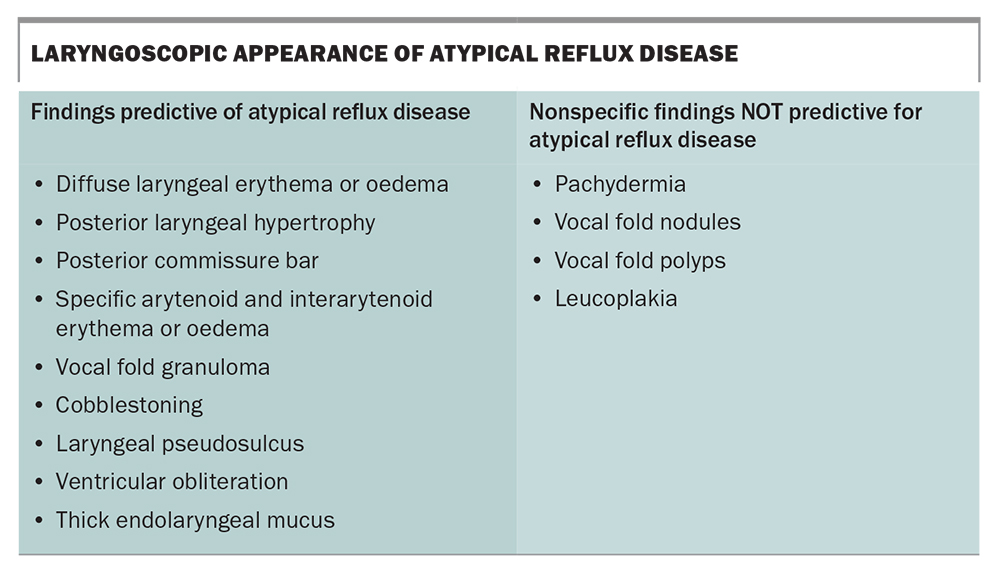

Specialist ENT review should be obtained for all patients with laryngopharyngeal symptoms. Although quite limited in its diagnostic value in atypical reflux disease, nasal pharyngoscopy with specialist ENT review helps to exclude differential diagnoses. A small subset of patients may display changes in the larynx and pharynx to support a diagnosis of atypical reflux disease; however, most patients exhibit limited findings on examination and many of these observable changes can occur in patients who are completely asymptomatic (Box).15 Alternative diagnoses will be established in some cases.

Gastroscopy is a diagnostic tool that largely excludes other diseases and is insensitive to the presence of gastro-oesophageal reflux (typical or atypical). Oesophagitis is absent in most cases of reflux and only higher grades are diagnostic of the disease; gastroscopy is only 30% diagnostic of reflux disease. It can be used to exclude upper gastrointestinal disease in patients with ‘alarm’ symptoms, such as gastric dyspepsia of new onset, anaemia, weight loss, dysphagia, vomiting, anorexia, haematemesis and melaena.

Oesophageal physiological studies may be appropriate in patients with particularly bothersome symptoms that are resistant to treatment. Such studies include oesophageal high-resolution manometry, multichannel pH and impedance reflux 24-hour studies; assessment of gastric emptying can also be useful. Oesophageal physiological studies in patients with atypical reflux disease usually indicate abnormal oesophageal clearance; studies for typical reflux are frequently normal in such cases, as episodes are infrequent but travel to the pharynx.

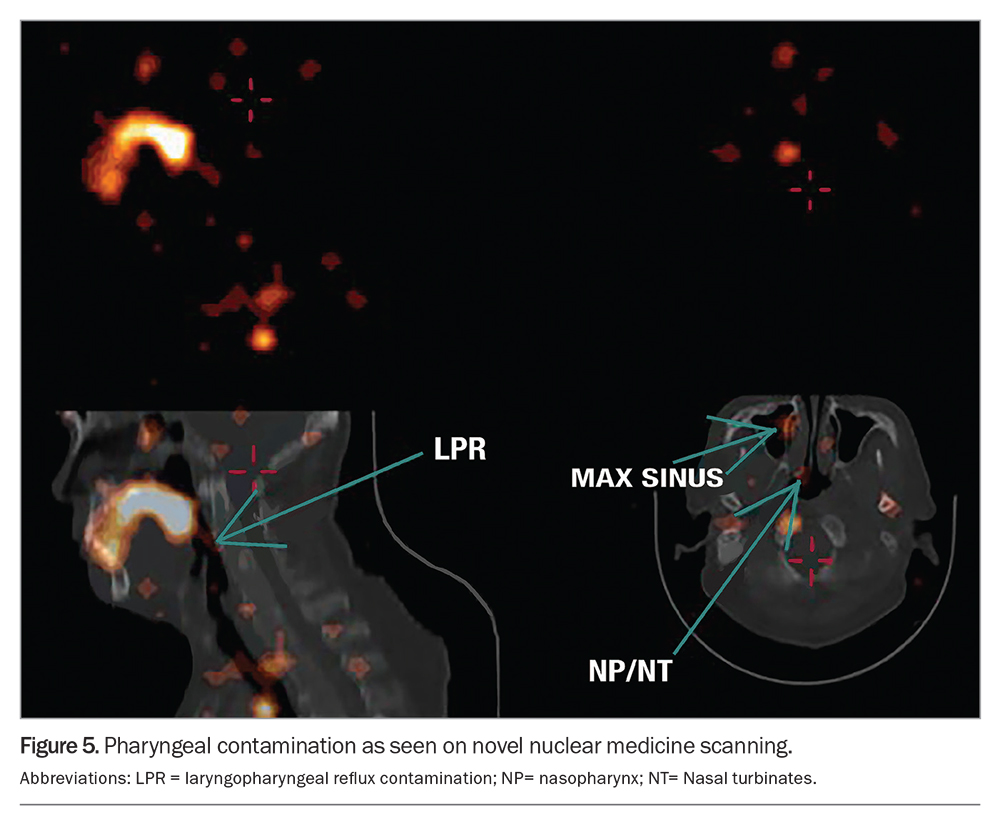

Neither 24-hour physiological studies nor endoscopy have proven to be overly sensitive in diagnosing atypical reflux disease. A new and reliable means of testing for atypical reflux disease has come with the recent development of pulmonary and pharyngeal microaspiration scanning.

Pulmonary and pharyngeal microaspiration scanning

Novel pulmonary and pharyngeal microaspiration scanning demonstrates that ‘silent’ regurgitation of gastric contents occurs in patients with laryngeal or pharyngeal symptoms of atypical reflux disease and that this regurgitation does not occur in the general population.12,16,17 The scanning identifies pharyngeal or laryngeal gastric reflux contamination and pulmonary microaspiration (Figure 5).18,19 Although such testing is not readily available, it can be used to diagnose atypical reflux disease; older modalities of ‘reflux scanning’ have proven to be insensitive and outmoded, by comparison.

Management

Atypical reflux disease is usually managed poorly. Although a complete reduction in symptoms is rarely achievable, most patients with atypical reflux disease will benefit from a six-week trial of alginate, a reduction in the size of meals consumed, the adoption of a raised sleeping position and the prescription of prokinetic therapy.

It is useful to consider the symptoms of atypical reflux disease as throat predominant (Flowchart 1) or cough predominant (Flowchart 2) and management should be catered to the symptoms that are the most problematic for the patient.

Acid suppression

Acid suppression with the prescription of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is commonly used to manage symptoms of heartburn as seen in typical reflux and throat-predominant atypical reflux disease. The consumption of a low acid diet, the use of a raised sleeping position and an avoidance of overeating can all be useful adjuncts. Although PPIs have proven effective for the management of patients with typical retrosternal heartburn, they provide little benefit in managing the extraoesophageal symptoms of atypical reflux, such as cough.20,21

PPIs do not stop droplet contamination, which, in addition to acid, contain pancreatic and biliary enzymes, bacteria and other nonacidic components of gastric fluid. Some studies indicate that PPIs may be associated with worsening chest infections, potentially due to the increased bacterial load in pH-neutral aspirated stomach fluid.22,23 Improvement in symptoms has occasionally been recognised with the use of H2 antagonists (particularly nizatidine) in patients with atypical reflux disease.

Randomised control trials demonstrate the lack of efficacy of single- or double-dose PPIs in patients with laryngeal symptoms.20,21,24-27 It is important to recognise that the designs of these studies lack an accurate diagnostic tool for the assessment of typical versus atypical reflux disease, resulting in heterogeneity of most of the selected patient cohorts. The diagnosis of atypical reflux disease (or lack thereof) will continue to confound such studies and make their results nonpredictive, until an adequate diagnostic tool is adopted and widely used.

Treatment with acid suppression therapy (PPI with or without an H2 antagonist) should be trialled for six to eight weeks, with an understanding that most patients will not notice a change in their symptoms. Specialist referral is then indicated, should symptoms persist.

Prokinetic therapy

The presence of early satiety, upper abdominal postprandial bloating or epigastric nonulcer dyspepsia may indicate abnormality of gastric peristaltic function. When confirmed on gastric motility studies (standard nuclear medicine techniques are not adequate), such cases may improve with the use of using prokinetic therapy, such as metoclopramide or domperidone.28,29

Alginate

Alginate is superior to simple antacids in treating typical reflux disease.30 The use of alginate in atypical reflux disease has been a longstanding clinical standard, with isolated cases confirming a reduction in the frequency of ‘silent’ regurgitation events. Alginate should be taken after eating and before bed. There is evidence supporting its use, both as a single therapy and in combination with other acid suppression treatments.31,32

Lifestyle modification

The symptoms of atypical reflux disease can be improved by the patient using a shoulder-elevated sleeping position, reducing the size of individual meals and avoiding large meals in the evening. A randomised controlled trial demonstrated partial efficacy with the adoption of a low-fat vegetarian diet.33 Patients with typical reflux disease who have a higher body mass index experience more severe symptoms than patients with normal body habitus, but whether weight loss assists in the management of atypical reflux disease remains uncertain.

As the regurgitation events of atypical reflux disease are largely nonacidic, the standard antireflux diet for the management of heartburn is unlikely to be of benefit and is therefore not supported. The volume of food at each meal may be contributory, especially considering the high frequency of gastric-emptying abnormalities in patients with atypical reflux disease. Such patients frequently report a worsening of symptoms following the consumption of substances that are known to reduce the pressure in the lower oesophageal sphincter, including coffee, chocolate, peppermint, alcohol, garlic and nicotine. A reduction in these substances is strongly suggested for the duration of treatment and can be modestly reintroduced when the symptoms of atypical reflux disease abate.

Surgery

Laparoscopic antireflux surgery appears to have little benefit in managing the symptoms of atypical reflux disease.34,35 Surgical treatment is incomplete and unpredictable in most patients, which may be due to the high rate of motility disorders of the oesophagus and stomach that exists preoperatively. This poorer outcome in patients with atypical reflux disease is in contradistinction to the well-established efficacy of antireflux surgery in reducing heartburn and regurgitation symptoms in patients with typical reflux disease.

Antireflux surgery should be considered in patients with pulmonary contamination and severe pulmonary disease for the treatment of aspiration, but with the understanding that such procedures are only partially effective.36 Antireflux surgery is not routinely recommended for patients with atypical reflux disease.

Conclusion

Atypical reflux disease has long been incorrectly conflated with typical reflux disease, despite significant differences in their physiology. Diagnosis remains inconsistent and inaccurate. No single investigation for atypical reflux disease exists, but measurements provided by pulmonary and pharyngeal microaspiration scanning may accurately support the diagnosis and eliminate inaccuracies in future research. Management should be directed at the physiological abnormalities of atypical reflux disease, such as oesophageal motility disorder leading to ‘silent’ regurgitation events.

Atypical reflux disease does not usually respond to acid suppression, and PPIs should only be administered for therapy as a short-term trial with the expectation that most prescriptions are likely to be ineffective. Surgery is rarely indicated. Atypical reflux disease and respiratory symptoms occurring in the same patient should raise concerns of pulmonary injury secondary to aspiration of reflux contents. The lack of understanding of atypical reflux disease can cause significant frustration for doctors and their patients, resulting in an unnecessary use of resources. There is a substantial lack of data on atypical reflux disease and more research is required. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Kahrilas P, Altman K, Chang A, et al. Chronic cough due to gastroesophageal reflux in adults: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016; 150: 1341-1360.

2. Postma G. Laryngitis: from the ENT point of view. In: Vaezi M, ed. Extraesophageal reflux. 1st ed. San Diego, California: Plural Publishing; 2009. p. 51.

3. Simpson S. Refractory gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and laryngopharyngeal reflux - use the bottom up approach. Arch Gastroenterol Res 2020; 1: 95-104.

4. Hoppo T, Sanz A, Nason K, et al. How much pharyngeal exposure is ‘normal’? Normative data for laryngopharyngeal reflux events using hypopharyngeal multichannel intraluminal impedance (HMII). J Gastrointest Surg 2012; 16: 16-25.

5. Zerbib F, Bruley des Varannes S, Roman S, et al. Normal values and day-to-day variability of 24-h ambulatory oesophageal impedance-pH monitoring in a Belgian-French cohort of healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2005. 22(10): p. 1011-21.

6. Park JS, Van der Wall H, Falk G. Reduced mean baseline impedance aids diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Aust J Otolaryngol 2022; 5: 1-9.

7. Morice A, Dettmar P. Reflux Aspiration and Lung Disease. 1st ed. USA: Cham Springer International Publishing; 2018.

8. Morice A. On chronic cough diagnosis, classification, and treatment. Lung 2021; 199: 433-434.

9. Vakil N, V van Zanten S, Kahrilas P, et al., The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 1900-1920.

10. Khoma O, Mendu M, Sen A, et al. Reflux aspiration associated with oesophageal dysmotility but not delayed liquid gastric emptying. Dig Dis 2021; 39: 429-434.

11. Belafsky P, Postma G, Koufman K. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). J Voice 2002; 16: 274-277.

12. Burton L, Joffe D, Mackey D, et al., A transformational change in scintigraphic gastroesophageal reflux studies: a comparison with historic techniques. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2021; 41: 136-145.

13. Morice A, Fontana G, Belsivi M, et al. ERS guidelines on the assessment of cough. Eur Respir J 2007; 29: 1256-1276.

14. Morice A, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, et al. ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901136.

15. Hicks D, Ours T, Abelson T, et al. The prevalence of hypopharynx findings associated with gastroesophageal reflux in normal volunteers. J Voice 2002; 16: 564-579.

16. Burton L, Baumgart K, Novakovic D, et al. Fungal pneumonia in the immunocompetent host: a possible statistical connection between allergic fungal sinusitis with polyposis and recurrent pulmonary infection detected by gastroesophageal reflux disease scintigraphy. Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther 2020; 29: 72-78.

17. Burton L, Falk G, Beattie J, et al. Findings from a novel scintigraphic gastroesophageal reflux study in asymptomatic volunteers. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2020; 10: 342-348.

18. Burton L, Falk G, Parsons S, et al. Benchmarking of a simple scintigraphic test for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease that assesses oesophageal disease and its pulmonary complications. Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther 2018; 27: 113-120.

19. Khoma O, Burton L, Falk M, et al. Predictors of reflux aspiration and laryngo-pharyngeal reflux. Esophagus 2020; 17: 355-362.

20. Khoma O, Park J, Lee F, et al. Different clinical symptom patterns in patients with reflux micro-aspiration. ERJ Open Research, 2022. 8: 00508-2021.

21. Watson G, O’Hara J, Carding P, et al. TOPPITS: Trial of proton pump inhibitors in throat symptoms. Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2016; 17: 175.

22. Wang H, Svanström H, Wintzell V, et al. Association between proton pump inhibitor use and risk of pneumonia in children: nationwide self-controlled case series study in Sweden. BMJ Open, 2022; 12: e060771.

23. Jaynes M, Kumar A. The risks of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: a critical review. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2019; 10: 2042098618809927.

24. Qadeer M, Phillips C, Lopez A, et al. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for suspected GERD-related chronic laryngitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 2646-2654.

25. Liu C, Wang H, Liu K. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of proton pump inhibitors for the symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Braz J Med Biol Res 2016; 49: e5149.

26. Jin X, Zhou X, Fan Z, et al. Meta-analysis of proton pump inhibitors in the treatment of pharyngeal reflux disease. Comput Math Methods Med 2022; 2022: 9105814.

27. O’Hara J, Watson G, Fouweather T, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors to treat persistent throat symptoms: multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2021; 372: m4903.

28. Ziessman H, Chander A, Clarke J, et al. The added diagnostic value of liquid gastric emptying compared with solid emptying alone. J Nucl Med 2009; 50: 726-731.

29. Bennink R, Peeters M, Van den Maegdenbergh V, et al. Evaluation of small-bowel transit for solid and liquid test meal in healthy men and women. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine 1999; 26: 1560-1566.

30. Leiman D, Riff B, Morgan S et al. Alginate therapy is effective treatment for GERD symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 2017; 30: 1-9.

31. Wilkie M, Fraser H, Raja H. Gaviscon® Advance alone versus co-prescription of Gaviscon® Advance and proton pump inhibitors in the treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2018; 275: 2515-2521.

32. Bianchetti M, Peralta S, Nicita R, et al. Emerging from gastroesophageal reflux (EMERGE): an Italian survey - I the viewpoint of the gastroenterologist. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2018; 32: 973-981.

33. Lechien J, Crevier-Buchman L, Distinguin Lea, et al. Is diet sufficient as laryngopharyngeal reflux treatment? A cross-over observational study. Laryngoscope 2022; 132: 1916-1923.

34. Falk G, Gooley S, Church N, Rangiah D. How effective is the control of laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms by fundoplication? Symptom score analysis. European Surgery 2020; 52: 123-126.

35. Morice D, Elhassan H, Myint-Wilks L, et al. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: is laparoscopic fundoplication an effective treatment? Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2022; 104: 79-87.

36. Khoma O, Falk S, Burton L, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and aspiration: does laparoscopic fundoplication significantly decrease pulmonary aspiration? Lung 2018; 196: 491-496.