Neurodegenerative disorders: a multidisciplinary approach to care

People living with neurodegenerative disorders have diverse and complex needs that demand a multidisciplinary approach to care, with GPs being key members of the team. There is a need to improve care integration to achieve optimal care experiences and health outcomes for patients and their families.

- Neurodegenerative disorders are a group of progressive neurological diseases typically characterised by a broad range of symptoms that manifest in complex and highly individualised ways.

- Care for patients and their families necessitates a multidisciplinary team approach involving a partnership triad between patients and their families, their healthcare team and the community.

- The multidisciplinary team includes medical practitioners, nurses, allied health professionals and community supporters. Understanding and respecting the roles of each discipline contribute to improved collaborative care.

- Patients and their families value good collaboration, communication, care co-ordination, continuity of care and compassion for improving their care experiences and health outcomes.

Neurodegenerative disorders are a group of diseases characterised by the progressive degeneration of neurons in the central nervous system. As a result, the affected individual experiences a decline in various neurological functions, such as cognition, movement, balance, speech and swallowing. Although there are similarities in progression among the group of diseases, there are also unique factors for each disease, and each person will present and progress in their own unique way.

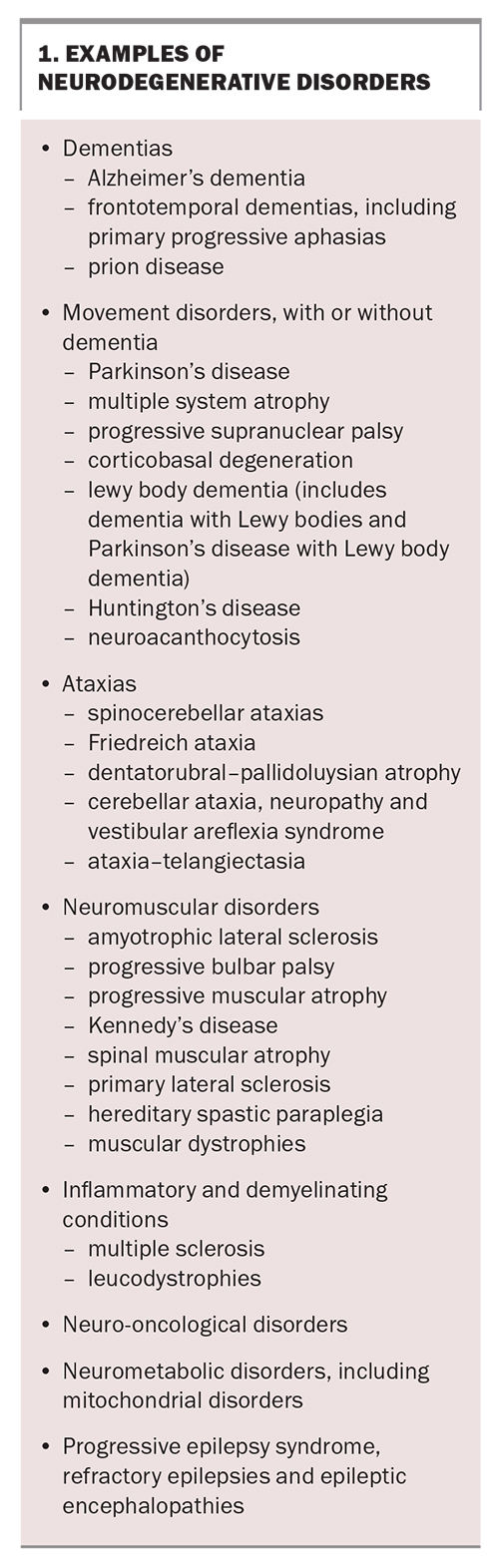

Box 1 lists examples of neurodegenerative disorders. The most common neurodegenerative disorders are:

- dementia (prevalence: 700 per 100,000)

- Parkinson’s disease (110 to 180 per 100,000)

- multiple sclerosis (80 to 140 per 100,000)

- motor neurone disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (6 to 7 per 100,000)

- progressive supranuclear palsy (7 per 100,000)

- Huntington’s disease (6 per 100,000)

- multiple system atrophy (5 per 100,000).1

Neurodegenerative disorders are prominent contributors to mortality, morbidity and disability worldwide. Preventive or curative treatments are yet to be established for these diseases, and the broad-ranging manifestations pose a significant challenge to patients, their caregivers, health professionals and healthcare systems. Consistently, guidelines recommend multidisciplinary care to address the diverse and complex care needs of people living with neurodegenerative disorders.2-4 Multidisciplinary care has been shown to improve the quality of life in people with neurodegenerative disorders, as well as improve caregiver well-being.5-8 It has also been shown to extend survival in people with life-limiting illnesses, such as motor neurone disease.9 This article describes the roles of each discipline and discusses factors valued by patients and their families for improving their care experiences and health outcomes.

What is multidisciplinary care in the context of neurodegenerative disorders?

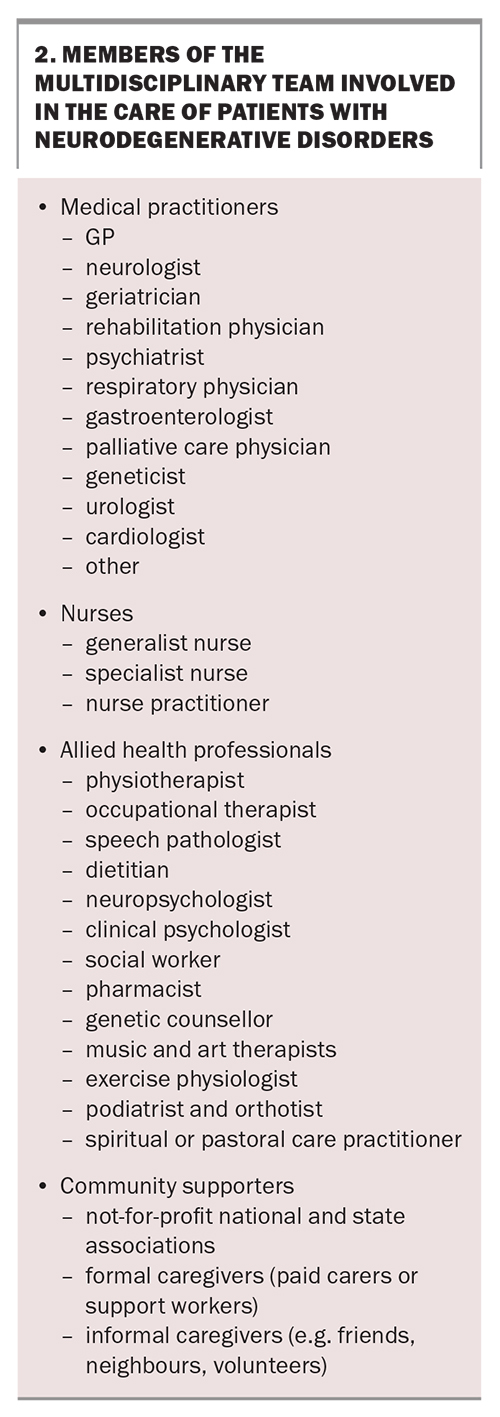

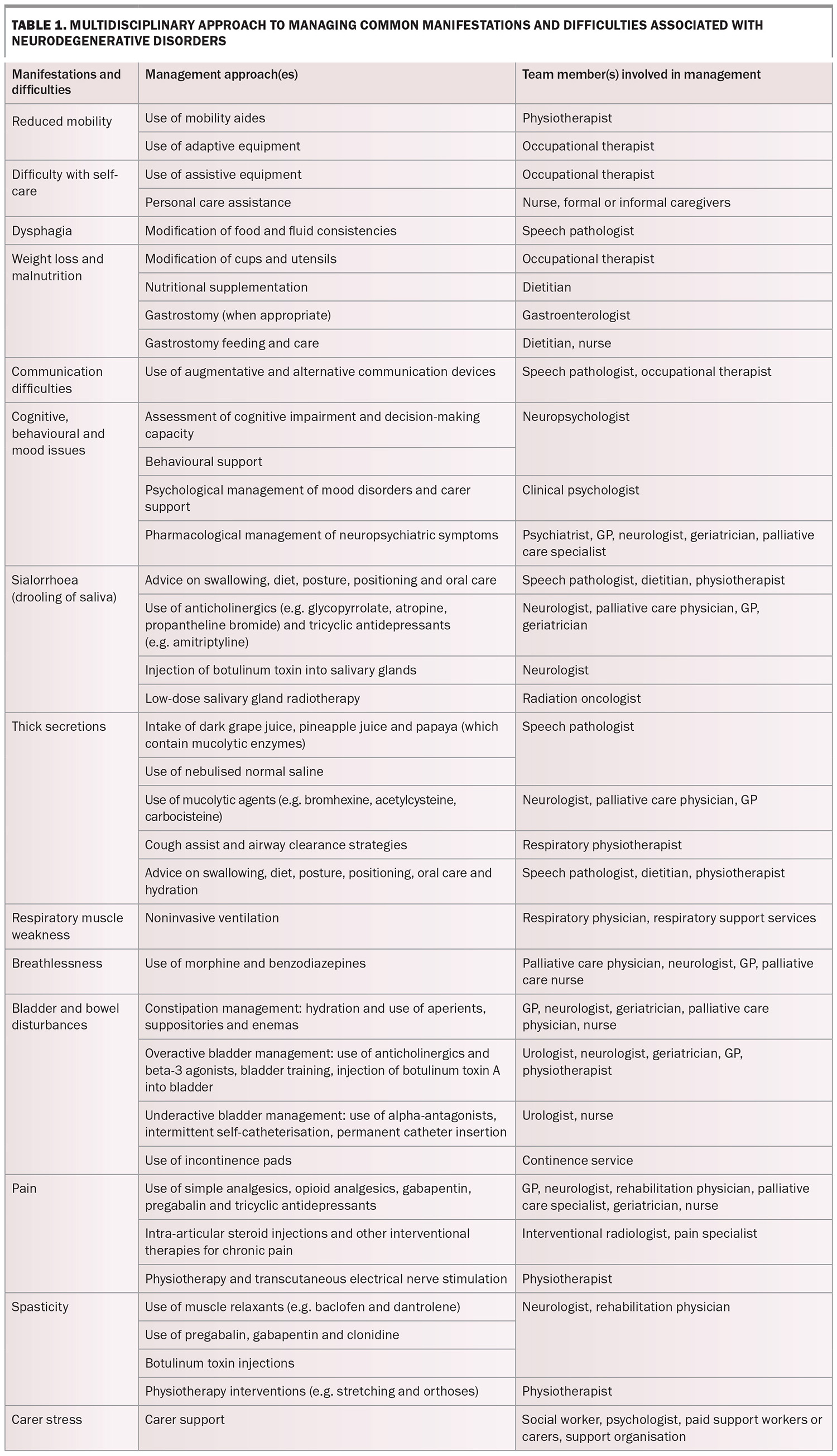

Multidisciplinary care is defined as a collaboration among professionals from a range of disciplines aimed at achieving optimal care for patients and their families. To address the multitude of problems posed by neurodegenerative disorders comprehensively, multidisciplinary care includes medical practitioners, generalist and specialist nurses, allied health professionals and community supporters, including formal and informal caregivers, and national and state voluntary support organisations. Box 2 lists the members of a typical multidisciplinary team involved in the care of patients with neurodegenerative disorders. Table 1 outlines the multidisciplinary approach to managing common manifestations and difficulties associated with neurodegenerative disorders.

What is the aim of the multidisciplinary team?

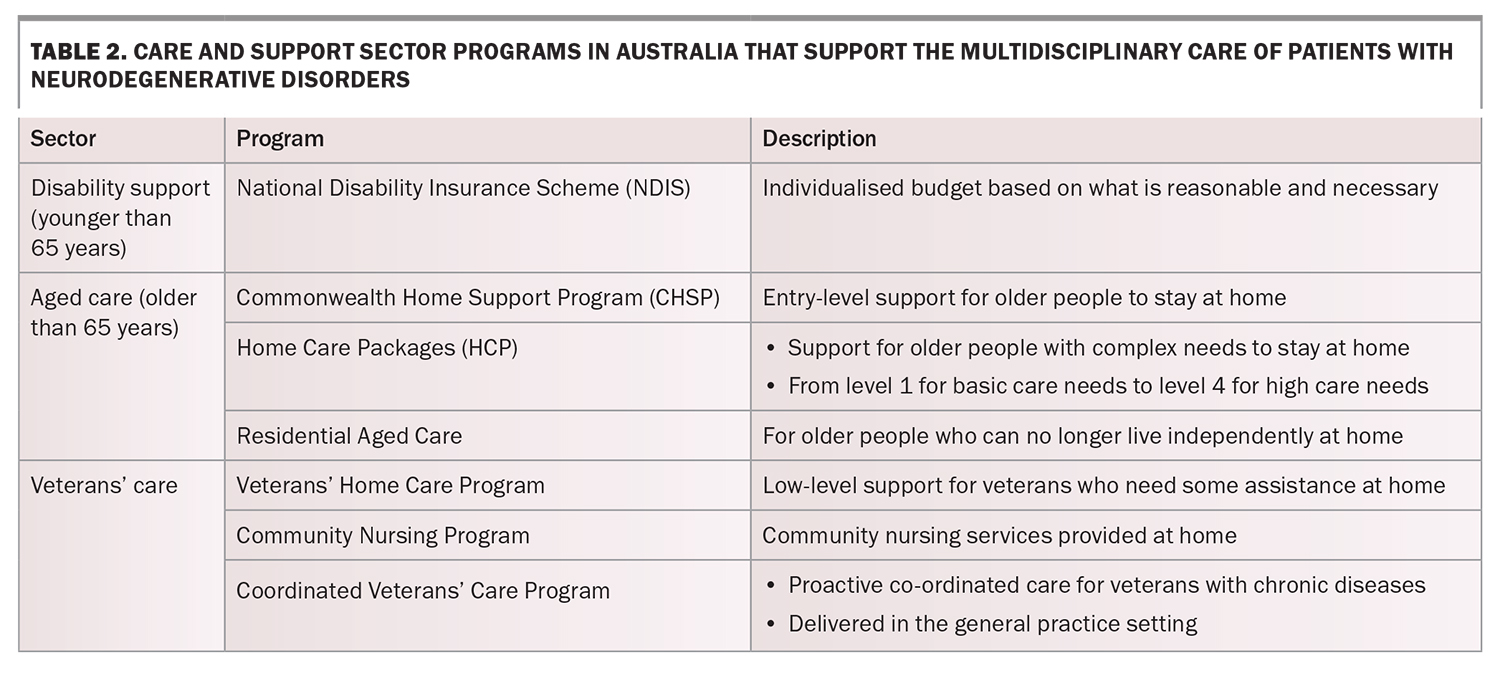

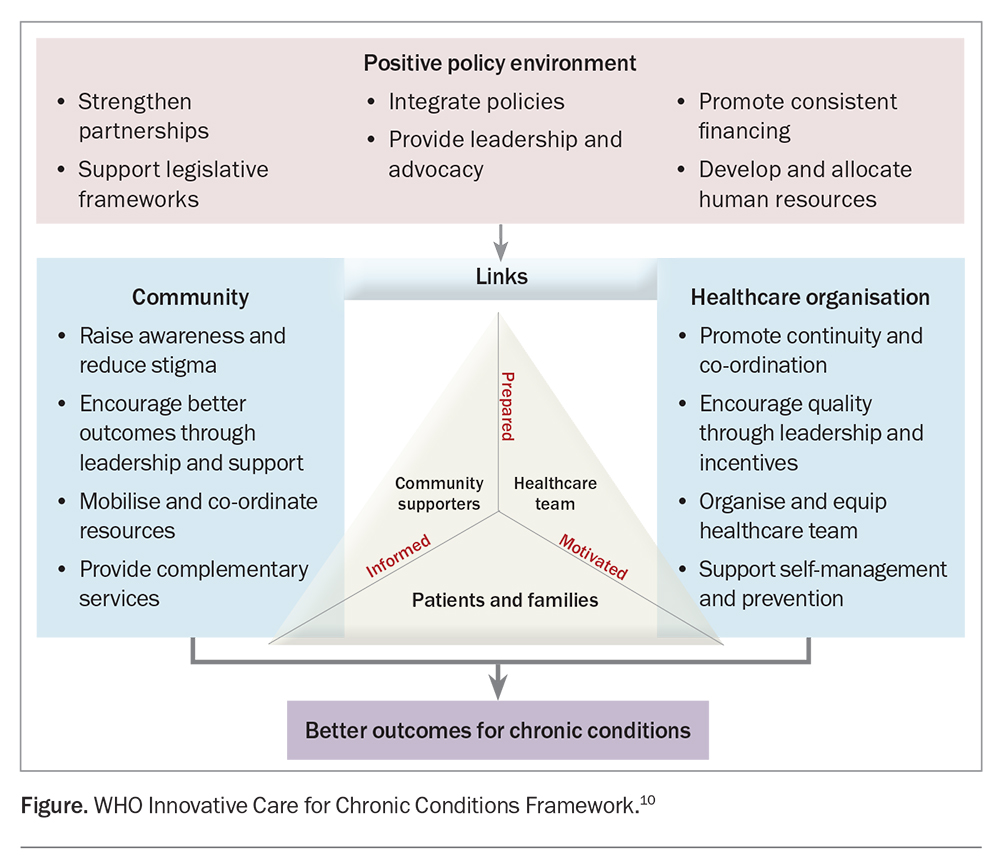

The multidisciplinary team aims to deliver integrated care across the healthcare sector (primary, specialist and hospital care) and care and support sectors (aged care, disability support and veterans’ care; Table 2), centred around the needs of patients and their families. Based on the WHO Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions Framework, a partnership triad is formed between the patient and family, their healthcare team and community, and the triad is then supported by the larger healthcare organisation, broader community and policy environment (Figure).10 Care is integrated within the triad through effective communication, collaboration, co-ordination and continuity of care. Integrated care leads to improvements in health outcomes, efficiency and patient and family experiences.11

What are the roles of the members of the multidisciplinary team?

Medical practitioners

General practitioners

GPs may be the only team members with longitudinal and contextual knowledge of a patient acquired through years of the doctor–patient relationship. They are the first point of contact for advice, diagnosis and management within the practice population, whether in the clinic, home, residential care or hospital. If the case falls outside their scope of practice, GPs can facilitate the required referrals. GPs may need to act in the role of a case manager, liaising with the community health team and specialist services and co-ordinating the patient’s care.12 In Australia, GPs develop GP management plans and team care arrangements under Medicare for patients with chronic diseases requiring multidisciplinary care (https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/chronic-disease-gp-management-plans-and-team-care-arrangements). GPs also play an essential role in advance care planning and providing palliative care through to the end of life for patients with terminal illnesses living in the community and residential care.

Neurologists

The role of neurologists begins with establishing the diagnosis and informing the patient, and extends to the management of various symptoms throughout the disease course. Their knowledge of the neurodegenerative disorder and its course is essential for informing shared care planning. In addition, neurologists have an active role in linking a patient’s care delivery with access to research, including registries and clinical trials of potential new therapies. In the late stage of the disease, neurologists aid with the identification and prognostication of patients who require specialist palliative care.13

Geriatricians

In Australia, geriatricians play an active role in the diagnosis and management of neurodegenerative disorders, such as dementia and Parkinson’s disease, in older people. Their core skills include understanding the impacts of conditions such as frailty, multimorbidity, dementia, delirium, polypharmacy, incontinence and falls.14 Geriatricians are part of the Aged Care Assessment Team (https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/assessment-for-aged-care), which assesses the care requirements of older people who need to access Commonwealth-funded community or residential aged care services as their illness progresses.

Rehabilitation physicians

Rehabilitation physicians use a holistic approach to maximise a patient’s function and independence, minimise disability and manage or limit complications associated with neurodegenerative disorders, such as pain, constipation, pressure injuries, spasticity and contractures. Some rehabilitation physicians have additional qualifications in interventional techniques for pain and spasticity management, such as performing nerve blocks and administering botulinum toxin injections.

Respiratory physicians

Respiratory compromise is common in the more advanced stages of many neurodegenerative disorders. The causes include respiratory muscle weakness (RMW) or central hypopnea, aspiration and recurrent lower respiratory tract infections. In motor neurone disease, RMW may be present at the time of diagnosis, eventually leading to respiratory failure and death.15 RMW often goes unrecognised as symptoms may appear subtle and can include:

- poor sleep quality

- daytime fatigue or somnolence

- morning headaches

- poor concentration or memory

- irritability

- dyspnoea on exertion, when lying supine or when immersed in water.

The diagnosis of RMW is established via history taking and examination, lung function testing or blood gas analysis. Noninvasive ventilation, when initiated early via referral to a respiratory physician, may improve respiratory symptoms, sleep quality, quality of life and survival.16,17 Therefore, it is important that RMW is diagnosed early, followed by prompt referral of the patient to a respiratory physician.

Gastroenterologists

Dysphagia and episodes of aspiration are common complications encountered in the more advanced stages of most neurodegenerative disorders. Advice should be sought from speech pathologists and dietitians to help guide oral intake that is as safe as possible. When appropriate, prompt referral to a gastroenterologist allows for early planning for the placement of a gastrostomy feeding tube to assist with nutrition, hydration and medication administration and reduce concerns related to meals that may be difficult to consume. Research in the areas of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and motor neurone disease suggests that patients may benefit from an early gastrostomy before substantial, potentially irreversible weight loss ensues.18 In other cases, such as in patients with advanced dementia or diseases with a poor prognosis, gastrostomy placement may not be appropriate.19 In patients with comorbid dysphagia and Parkinson’s disease, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement for nutritional support is associated with a 30-day mortality rate of 6%, higher rates of discharge to a nursing home and a common complication of aspiration pneumonia.20

Urologists

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are common in patients with dementia, Parkinsonian disorders and rarer neurodegenerative disorders such as Huntington’s disease and hereditary ataxias.21 Specific pathologies (such as those in Parkinson’s disease) or more complex mechanisms that interact with behavioural functions and basic daily management (such as those in dementia) may contribute to LUTS. Frequent urination, urgency, incontinence and poor bladder emptying are the most common symptoms. LUTS impair a patient’s quality of life and contribute to medical morbidity, poor self-esteem, a loss of independence, stress for caregivers and significant financial burden.22 Careful evaluation and management of LUTS, with support from a continence service and urologists, can help improve the quality of life of patients and their caregivers.

Treatment of LUTS should be tailored to individual patient needs and account for factors such as a patient’s mobility, cognitive function and general medical condition. A conservative approach may include bladder retraining and scheduled toileting, controlling fluid intake, avoiding caffeinated drinks, the use of absorbent products for incontinence, and pelvic floor exercises and biofeedback for people without significant cognitive impairment.23 Before medical management can begin, urinary retention must be ruled out. Medications such as anticholinergics and smooth muscle relaxants must be used with caution, and patients must be monitored for adverse effects such as worsening cognition and constipation. Urologists may assist with the management of urinary retention or concomitant bladder outlet obstruction, or with minimally invasive management, when appropriate.

Psychiatrists

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, psychosis, irritability and behavioural changes, are common in patients with neurodegenerative disorders, particularly dementia, Huntington’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and related disorders, multiple sclerosis and prion disease. These symptoms can cause distress and reduce the quality of life of patients and their caregivers, increase caregiver burden and increase the risk of institutionalisation.24,25 Psychiatrists, including old age psychiatrists and neuropsychiatrists, have a key role in assessing and managing neuropsychiatric symptoms, by incorporating psychological, behavioural and pharmacological interventions in the context of neurodegeneration and comorbid medical illness.

Palliative care physicians

Palliative care is an approach to care that is focused on patients and their families and considers the physical, psychosocial and spiritual dimensions, aiming to improve the quality of life of people living with life-limiting illnesses. There are unique palliative care challenges in neurodegenerative disorders, some of which include communication barriers resulting from speech or cognitive impairment, uncertainty in prognosis and existential distress related to the loss of identity. Primary palliative care (e.g. basic symptom management, basic discussions about prognosis and goals of care) should be provided within the skill set of all clinicians who care for people living with neurodegenerative disorders. However, more complex symptom management or difficult discussions about care goals that involve conflict may require the involvement of a specialist palliative care team. Other ‘triggers’ that have been suggested to guide referrals to palliative care services include rapid physical decline and recurrent infections.26,27

Nurses

Nurses are vital to caring for people with neurodegenerative disorders. Nursing practice has a special focus on medication management and bladder, bowel, skin and oral care. Nurses are often the first to attend when assistance is required by a patient in outpatient, inpatient, home (via a district nursing or community palliative care team) or residential care settings. Neurological nurse specialists have been embedded in the multidisciplinary care of patients with various neurodegenerative disorders in Australia for over two decades.28 Nurse specialists have a wide-reaching role that includes providing skilled nursing care and psychological and emotional support to patients and caregivers, delivering education, promoting self-management and co-ordinating referrals to the wider multidisciplinary team. Nurse practitioners have an advanced and extended clinical role and can prescribe some medications to assist with symptom management.

Allied health professionals

Physiotherapists

Physiotherapists aim to enhance a patient’s quality of life by maximising their physical ability and minimising secondary complications over the course of the neurodegenerative disease. Physiotherapy interventions focus on transfers, posture, upper limb function, balance and gait, and these may include the prescription of exercises and walking aids. They may also assist with the management of pain and respiratory problems, including the clearance of secretions.29

Occupational therapists

Occupational therapy aims to maximise a patient’s daily function and quality of life despite the inevitable progression of impairments associated with neurodegenerative disorders. To achieve this, occupational therapists use a combination of strategies, including movement and cognitive strategies, and adaptation of daily routines and the physical environment.30 Adaptations may include reorganising the daily routine, learning skills for alternative or adaptive ways to complete activities and providing aids and equipment, such as hoists, wheelchairs, commodes and hospital beds. Occupational therapists conduct home and driving assessments and recommend appropriate modifications for the car, home and workplace.

Speech pathologists

Speech pathologists have a key role in assessing and managing swallowing and communication problems associated with neurodegenerative disorders. For patients with dysphagia, speech pathologists assess aspiration risk and make recommendations on food and fluid consistency. They also recommend nonpharmacological management approaches for sialorrhoea (e.g. strategies to encourage more frequent swallowing of excess saliva) or thick secretions (e.g. a saline nebuliser).31 Changes in speech and communication can be distressing for patients, and speech pathologists can make recommendations on augmentative and alternative communication strategies, which may range from ‘low tech’ devices, such as the use of a writing board, to more complex technologies, such as eye gaze technology.

Dietitians

People with neurodegenerative disorders are at risk of malnutrition. The risk factors include oropharyngeal dysphagia, difficulty with self-feeding, cognitive impairment and depression. Malnutrition is associated with a poor prognosis, causing a faster rate of disease progression and an increased risk of institutionalisation, morbidity and mortality.32 Dietitians assist in preventing, assessing and managing weight loss and malnutrition throughout all stages of neurodegenerative disorders. Dietetic interventions may include the intake of supplements and food fortification. Where appropriate, dietitians provide management and education for patients and caregivers in relation to enteral feeding.

Social workers

Social workers help patients and their families cope with the psychosocial ramifications of neurodegenerative disorders, including the impact on relationships, parenting, employment, financial security, housing and participation in the community. They provide counselling for patients and their families and facilitate support groups. They also provide information on and facilitate access to community and residential services. Social workers provide advocacy and are a natural co-ordination point between patients and their health and community resources.33

Clinical psychologists and neuropsychologists

Clinical psychologists aim to reduce psychological distress by providing psychological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural therapy for mood, adjustment or sleep disorders, as well as relaxation training. They also assist with the management of caregiver burden or stress.

Neuropsychologists conduct neuropsychological assessments to detect and determine if the pattern of cognitive changes is consistent with a particular aetiology while concurrently identifying influencing factors such as depression, anxiety, vascular disease, substance use and medication effects.34 They provide cognitive training for compensatory strategies, memory support groups, psychoeducation and behavioural management support.

Community supporters

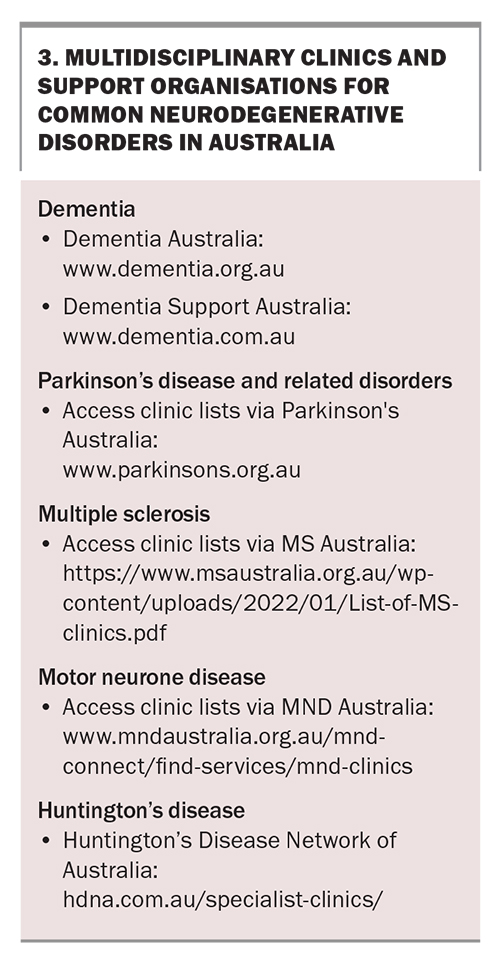

Healthcare for people with neurodegenerative disorders must extend beyond the clinic walls into their communities. The not-for-profit national and state associations in Australia, such as those for dementia, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease and Huntington’s disease, have key roles in raising awareness about the disease, providing support services and advocacy, and promoting and facilitating research (Box 3). The patient’s local community can also fill the gap in healthcare that may not be provided through formal services. An example is the Compassionate Communities Connectors Program in Western Australia (https://comcomnetworksw.com/), which enlists community volunteers to provide practical and social support for people with advanced chronic conditions and life-limiting illnesses. Evaluation of the program’s outcomes showed reduced social isolation, improved coping with daily activities and an increase in supportive networks.35

Patients and their families

Patients and their families are the most undervalued assets in the healthcare system. Their potential to affect outcomes should be leveraged fully. To manage their chronic, progressive diseases, they need information to promote health literacy, motivation to improve their health behaviours and support with self-management skills. Effective self-management (e.g. adherence to medications, consistent exercise and proper nutrition) helps minimise complications, symptoms and disabilities associated with the chronic condition.36

What have patients and families reported as missing from their care?

People with dementia and their caregivers have identified the need for improved access to support and services, and improved communication and attitudes of healthcare providers.37 In recent Australian surveys, people with Parkinson’s disease have prioritised the need for improved personalised healthcare information, better continuity of care and collaboration between healthcare professionals.38 People with multiple sclerosis have highlighted the need for greater transparency and communication.39 People with motor neurone disease and their caregivers have also emphasised the need for improved service co-ordination, empathy and professional knowledge.40 This information can assist Australian healthcare teams in better targeting their practice models to deliver more integrated care for people living with neurodegenerative disorders.

How can we improve care integration?

Understanding and respecting the roles of each discipline contribute to improved collaborative care. Effective collaboration and communication across disciplines and with patients and their families are essential to setting goals that most accurately reflect a patient’s needs. This is enabled by shared care planning and information exchange, utilising digital and assistive technologies and implementing telehealth. Medicare Benefits Schedule items 747, 750 and 758 support the participation of Australian GPs in multidisciplinary team meetings, which can take place either face to face, over the phone or via telehealth. Telehealth can also support the continuity of care for people who are unable to travel to the clinic and self-management (e.g. through the use of educational videos and health management apps for mobile devices). Intersectoral care co-ordination by a designated care co-ordinator, such as a nurse specialist or social worker, is important to reduce care fragmentation and duplication.

Conclusion

The model of care for people living with neurodegenerative disorders needs to adopt a multidisciplinary approach, with patients and their families as active participants in their care, supported by their healthcare team and community. Each member of the team is valued for their unique skills; however, there is a need to improve care integration to achieve optimal care experiences and health outcomes for patients and their families. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Lie and Associate Professor Mathers: None. Professor Phan has received support from Bayer, Pfizer and Boehringer Ingelheim. Professor Ma is a Founding Member of the Clinical Council of the Australasian Stroke Academy; Committee Member of the Stroke Society of Australasia; and Co-Chair of the Australian Stroke Trial Network.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Global burden of neurological disorders: estimates and projections. In: WHO, ed. Neurological disorders: public health challenges. Geneva: WHO; 2006. Available online at: Global burden of neurological disorders: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241563369 (accessed November 2023).

2. National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions (UK). Parkinson’s disease: National Clinical Guideline for Diagnosis and Management in Primary and Secondary Care. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2006.

3. Andersen PM, Abrahams S, Borasio GD, et al. EFNS guidelines on the clinical management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MALS) – revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19: 360-375.

4. Oliver DJ, Borasio GD, Caraceni A, et al. A consensus review on the development of palliative care for patients with chronic and progressive neurological diseases. Eur J Neurol 2016; 23: 30-38.

5. Wolfs C, Kessels A, Dirksen C, et al. Integrated multidisciplinary diagnostic approach for dementia care: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 192: 300-305.

6. van der Marck MA, Bloem BR, Borm GF, et al. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Mov Disord 2013; 28: 605-611.

7. Ng L, Khan F, Mathers S. Multidisciplinary care for adults with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 4: CD007425.

8. Gage H, Grainger L, Ting S, et al. Specialist rehabilitation for people with Parkinson’s disease in the community: a randomised controlled trial. Health Serv Deliv Res 2014; 2: 1-376.

9. Traynor BJ, Alexander M, Corr B, et al. Effect of a multidisciplinary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) clinic on ALS survival: a population based study, 1996-2000. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74: 1258-1261.

10. World Health Organization (WHO). Noncommunicable diseases and mental health cluster. Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for actions: global report. Geneva: WHO; 2002. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42500 (accessed November 2023).

11. Armitage GD, Suter E, Oelke ND, Adair CE. Health systems integration: state of the evidence. Int J Integr Care 2009; 9: e82.

12. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). What is general practice? Sydney: RACGP; 2023. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/education/students/a-career-in-general-practice/what-is-general-practice (accessed November 2023).

13. Holloway R G, Gramling R, Kelly AG. Estimating and communicating prognosis in advanced neurologic disease. Neurology 2013; 80: 764-772.

14. The Education Committee Writing Group of the American Geriatrics Society. Core competencies for the care of older patients: recommendations of the American Geriatrics Society. Acad Med 2000; 75: 252-255.

15. Schiffman P, Belsh JM. Pulmonary function at diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Chest 1993; 103: 508-513.

16. Bourke SC, Tomlinson M, Williams TL, et al. Effects of non-invasive ventilation on survival and quality of life in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2006; 5: 140-147.

17. Lechtzin N, Scott Y, Busse AM, et al. Early use of non‐invasive ventilation prolongs survival in subjects with ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2007; 8: 185-188.

18. ProGas Study Group. Gastrostomy in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ProGas): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 702-709.

19. Murphy LM, Lipman TO. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy does not prolong survival in patients with dementia. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 1351-1353.

20. Brown L, Oswal M, Samra AD, et al. Mortality and institutionalization after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in parkinson’s disease and related conditions. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2020; 7: 509-515.

21. Li FF, Cui YS, Yan R, et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms, urinary incontinence and retention in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Aging Neurosci 2022; 14: 977572.

22. Averbeck MA, Altaweel W, Manu-Marin A, Madersbacher H. Management of LUTS in patients with dementia and associated disorders. Neurourol Urodyn 2017; 36: 245-252.

23. Averbeck MA, Altaweel W, Manu-Marin A, et al. Management of LUTS in patients with dementia and associated disorders. Neurourol Urodyn 2017; 36: 245-252.

24. Okura T, Plassman BL, Steffens DC, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and the risk of institutionalization and death: the aging, demographics, and memory study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59: 473-481.

25. Silverman HE, Ake JM, Manoochehri M, et al. The contribution of behavioral features to caregiver burden in FTLD spectrum disorders. Alzheimers Dementia 2022; 18: 1635-1649.

26. National End of Life Care Programme. End of life care in long term neurological conditions: a framework for implementation. Dublin: Neurological Alliance of Ireland; 2010. Available online at: http://www.nai.ie/go/resources/guidance_policy_standards/guidance_policy_standards_uk_international/end-of-life-care-in-long-term-neurological-conditions (accessed November 2023).

27. Hussain J, Adams D, Allgar V, et al. Triggers in advanced neurological conditions: prediction and management of the terminal phase. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014; 4: 30-37.

28. Standards for Practice: Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Nurse Specialists, First edition. Melbourne: Australasian Neuroscience Nurses’ Association (Movement Disorder Chapter); 2017. Available online at: https://www.anna.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/PDMDNS-Standards-for-Practice-2017-09.pdf (accessed November 2023).

29. Chatwin M, Toussaint M, Gonçalves MR, et al. Airway clearance techniques in neuromuscular disorders: a state of the art review. Respir Med 2018; 136: 98-110.

30. Foster ER, Bedekar M, Tickle-Degnen L. Systematic review of the effectiveness of occupational therapy-related interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease. Am J Occup Ther. 2014; 68: 39-49.

31. McGeachan AJ, Mcdermott CJ. Management of oral secretions in neurological disease. Practical Neurol 2017; 17: 96-103.

32. Bianchi VE, Herrera PF, Laura R. Effect of nutrition on neurodegenerative diseases. A systematic review. Nutrition Neurosci 2021; 24: 810-834.

33. Vickrey B, Mittman BS, Connor KI, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Int Med 2006; 145: 713-726.

34. Pimentel ÉML. Role of neuropsychological assessment in the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Dement Neuropsychol 2009; 3: 214-221.

35. Aoun SM, Richmond R, Gunton K, Noonan K, Abel J, Rumbold B. The Compassionate Communities Connectors model for end-of-life care: Implementation and evaluation. Palliat Care Soc Pract 2022; 16: 26323524221139655.

36. Grady PA, Gough LL. Self-management: a comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. Am J Public Health 2014; 104: e25-e31.

37. Prorok JC, Horgan S, Seitz DP. Health care experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers: a meta-ethnographic analysis of qualitative studies. CMAJ 2013; 185: E669-E680.

38. Danoudis M, Soh SE, Iansek R. Health care experiences of people with Parkinson’s disease in Australia. BMC Geriatr 2023; 23: 430.

39. Price E, Lucas R, Lane J. Experiences of healthcare for people living with multiple sclerosis and their healthcare professionals. Health Expect 2021; 24: 2047-2056.

40. Velaga VC, Cook A, Auret K, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care for people living with motor neurone disease: ongoing challenges and necessity for shifting directions. Brain Sci 2023; 13: 920.