Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update

The incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is continuing to rise in Australia. As early-stage HCC is potentially curable, GPs play a pivotal role in identifying and managing risk factors to prevent its development, ensuring surveillance for high-risk individuals and arranging appropriate referral to non-GP specialists. HCC management should be driven by a multidisciplinary team, with available treatment options including surgical resection, locoregional therapies, liver transplantation and systemic therapies.

- GPs are well positioned to identify and manage risk factors for preventable cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), including chronic hepatitis B and C infection, obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease and excessive alcohol consumption.

- Early-stage HCC is potentially curable, so regular surveillance of patients at high risk of HCC is imperative for early detection.

- A multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and management is highly recommended.

- Treatment options are guided by the stage of HCC according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system.

- Newer systemic therapies (combination atezolizumab and bevacizumab, or lenvatinib) are now available for the treatment of advanced-stage HCC.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common type of primary liver cancer. With an annual incidence rate of 8.1 per 100,000 people, liver cancer is a substantial health concern in Australia.1 This incidence has risen markedly over the past three decades – a trend that is projected to continue in coming years.1 Liver cancer disproportionately affects people with socioeconomic and geographical disadvantage. Indigenous Australians face a threefold higher risk of developing liver cancer compared with their non-Indigenous counterparts.1 Disparities are also evident for people living in remote or very remote areas and economically disadvantaged areas, where incidence rates of liver cancer are 13% and 59% higher, respectively.1 There are also higher rates of liver cancer in migrants to Australia than in the Australian-born population, likely due to a higher prevalence of chronic hepatitis B infection in people born overseas.2

Although cure is possible for those with early-stage HCC, through resection, ablation or liver transplantation, many patients are diagnosed in the later stages of disease, which confer a poorer prognosis. With an overall five-year survival rate of 20%, liver cancer is the seventh most common cause of cancer death in Australia.1 Of concern, its mortality rate has increased by 304% in the past three decades.1

This article provides an update on the diagnosis and treatment of HCC, with a focus on areas where GPs can contribute to its prevention, early detection and management. It covers the latest available treatment options and their potential role in each stage of the disease.

Management of risk factors for HCC

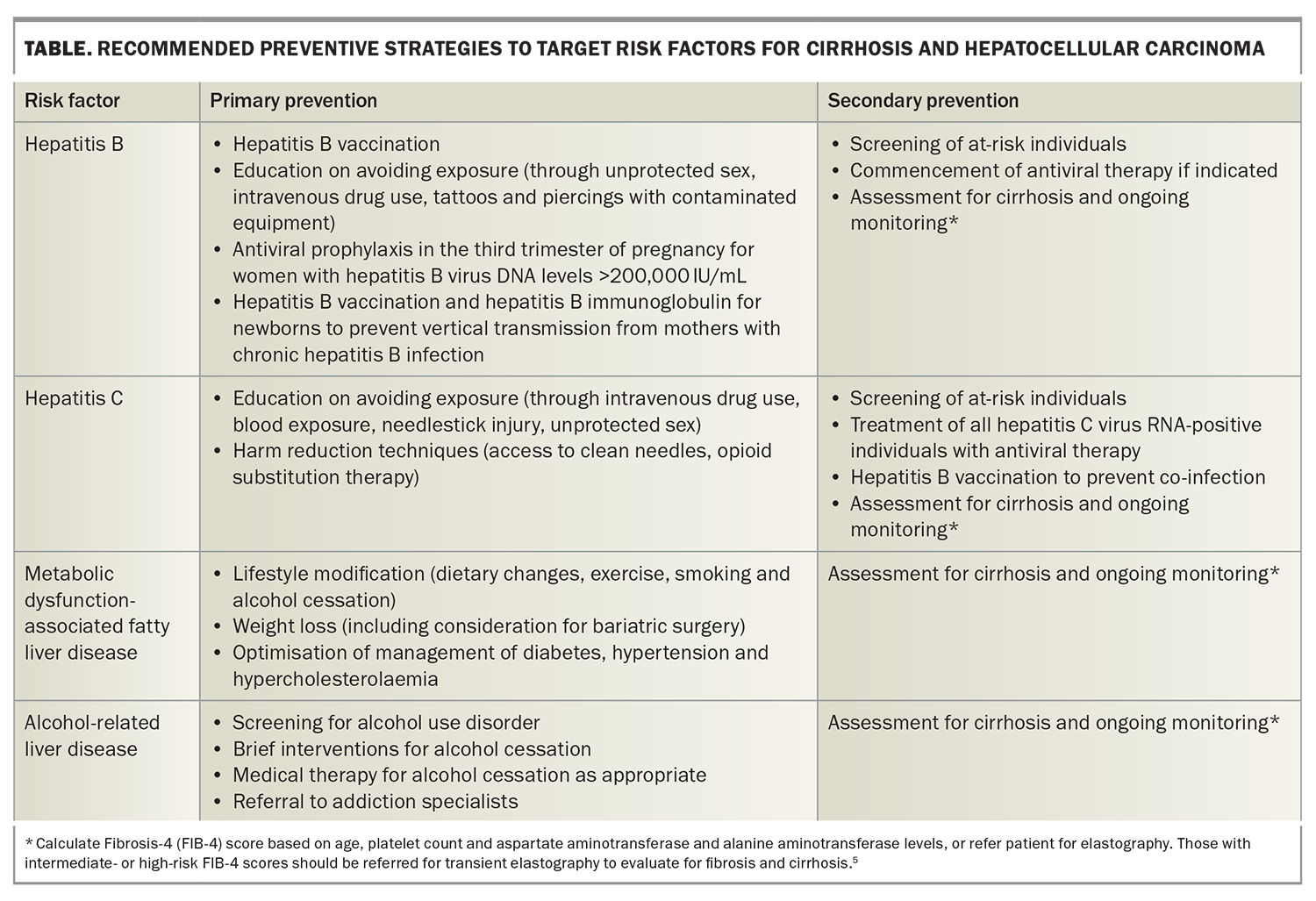

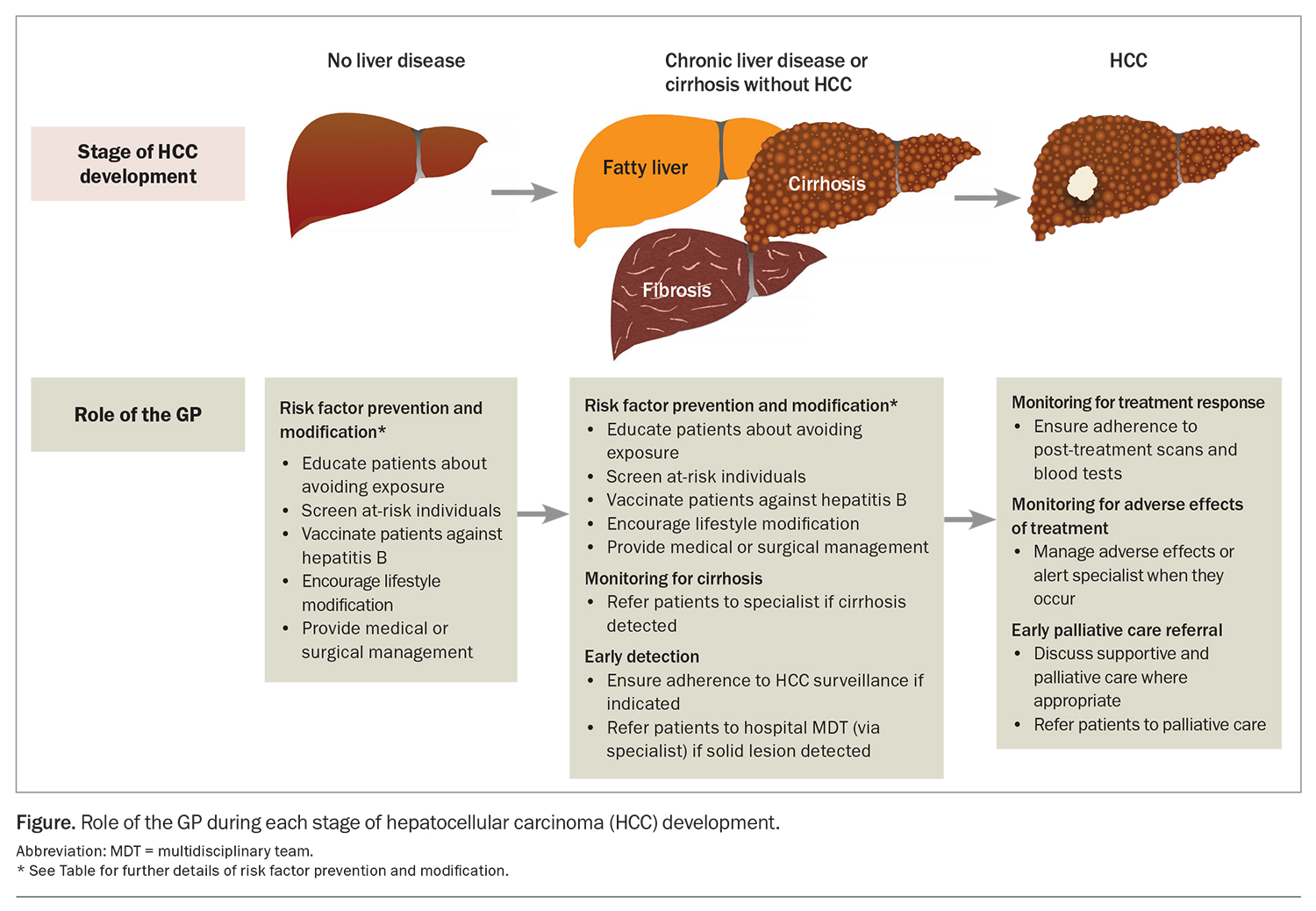

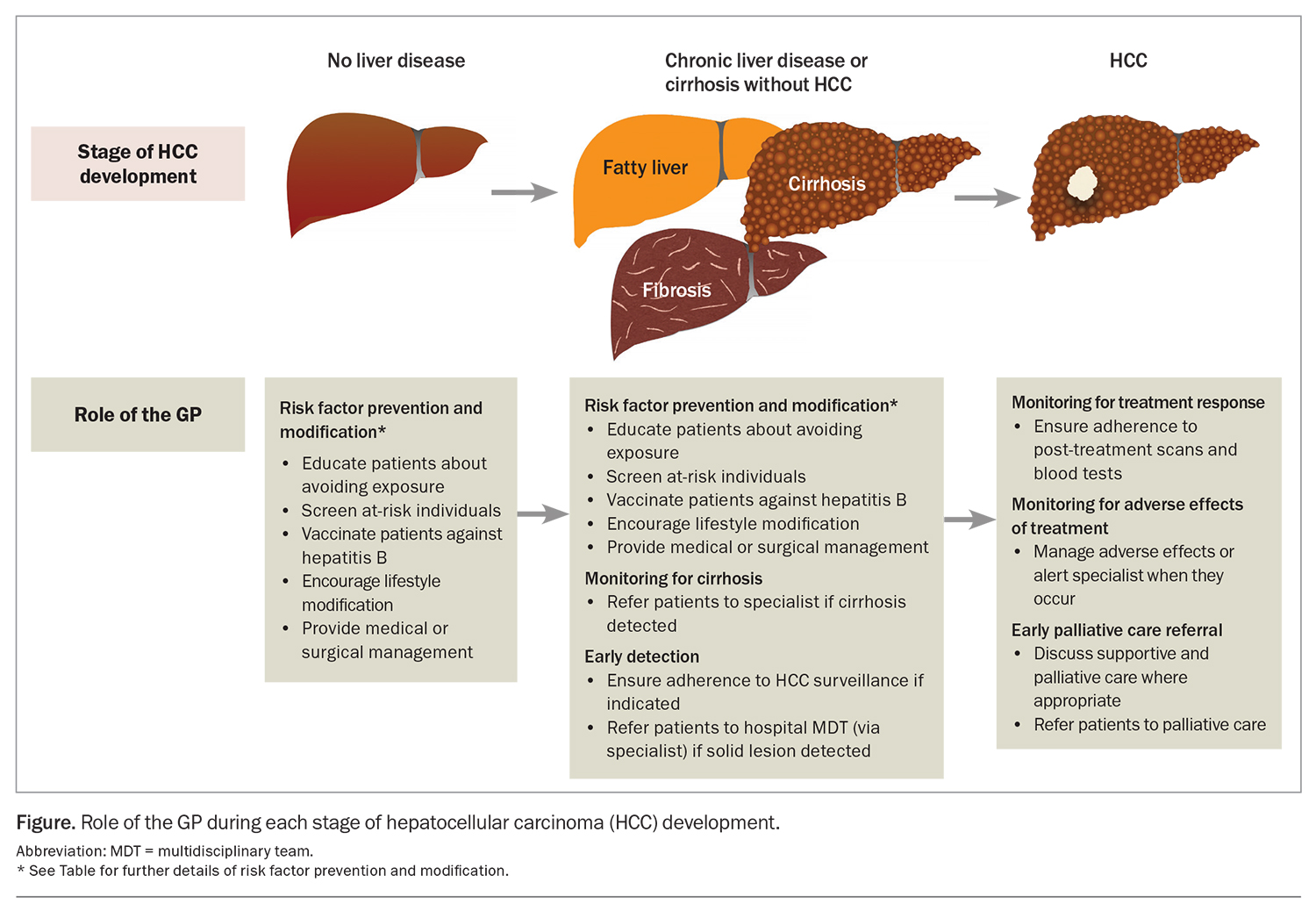

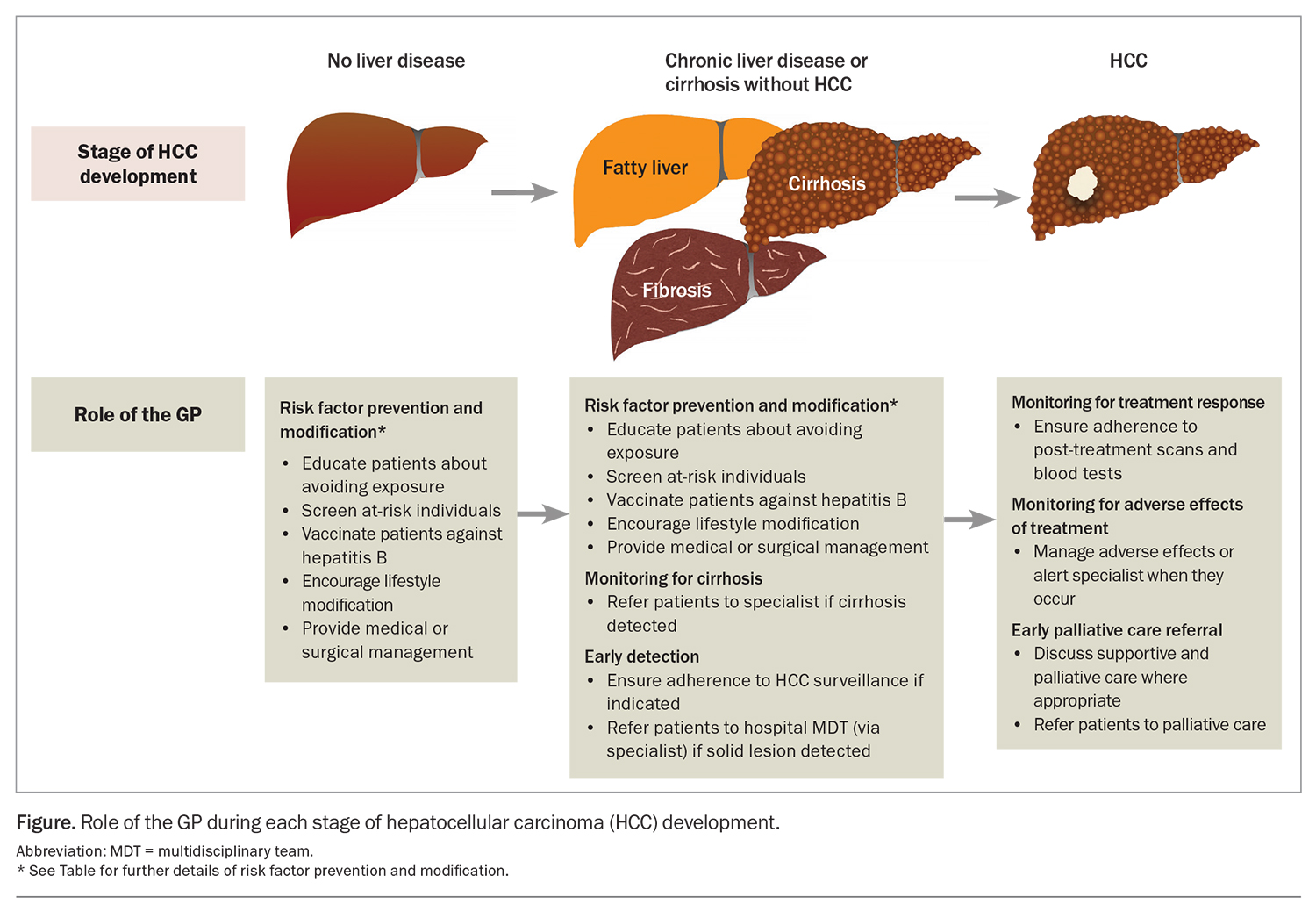

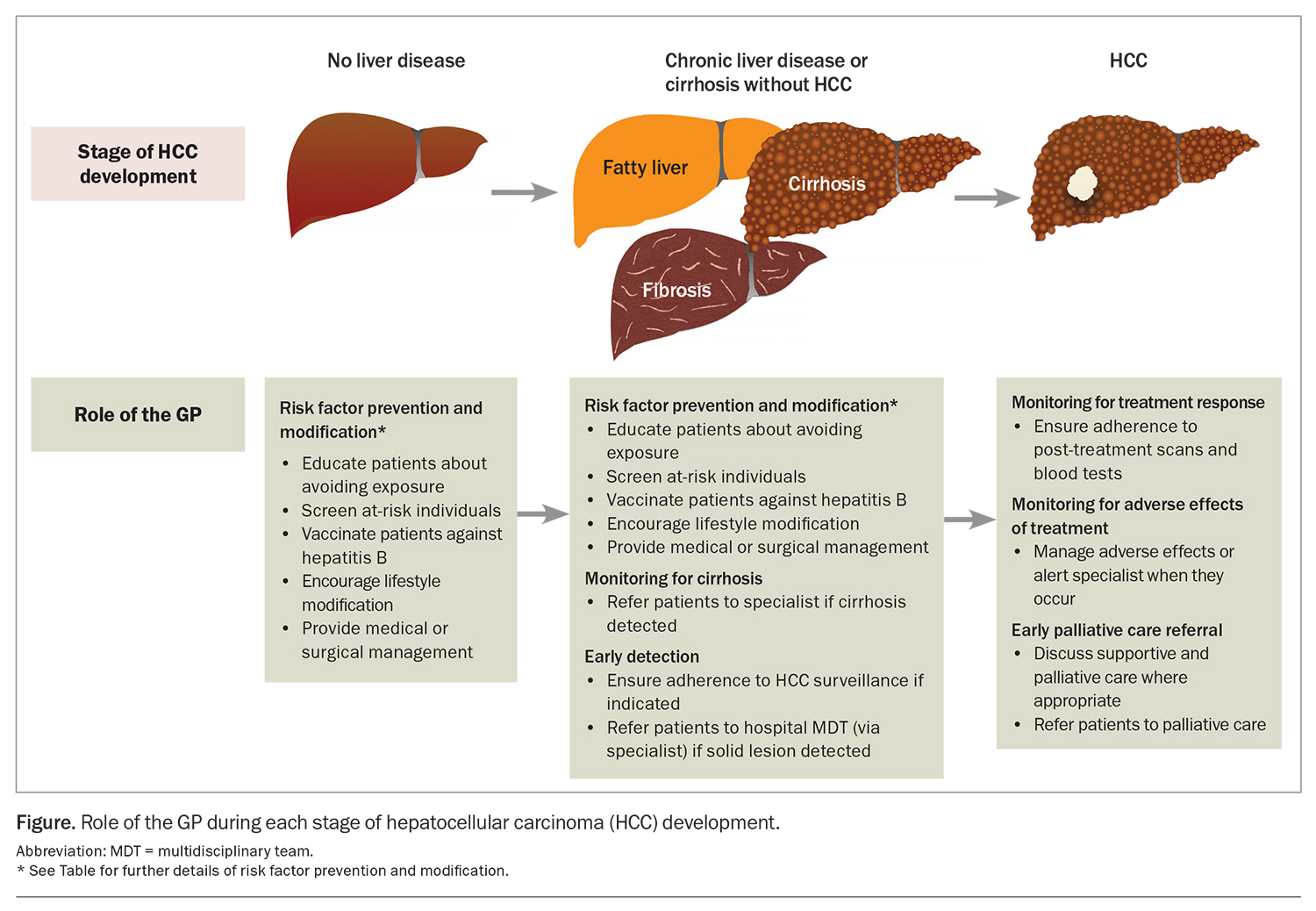

Cirrhosis from any cause increases the risk of HCC, and the annual incidence of HCC in patients with cirrhosis is 1.5%.3 Therefore, there is a need for measures to prevent the development of cirrhosis. The most common aetiologies of cirrhosis include chronic hepatitis B and C infection infection, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) and alcohol-related liver disease. Many of the common causes of cirrhosis can be prevented or mitigated through lifestyle modification and harm reduction strategies. For instance, patients should be counselled regarding alcohol and smoking cessation and linked with appropriate support networks.4 GPs are well placed to implement these and other preventive health practices to manage the risk factors associated with underlying causes of cirrhosis and HCC. The Table gives an overview of recommended primary and secondary prevention measures. By incorporating these measures into their clinical practice, GPs can contribute to reducing the incidence of cirrhosis, and therefore incident HCC, among their patients (Figure).

Hepatitis B and C

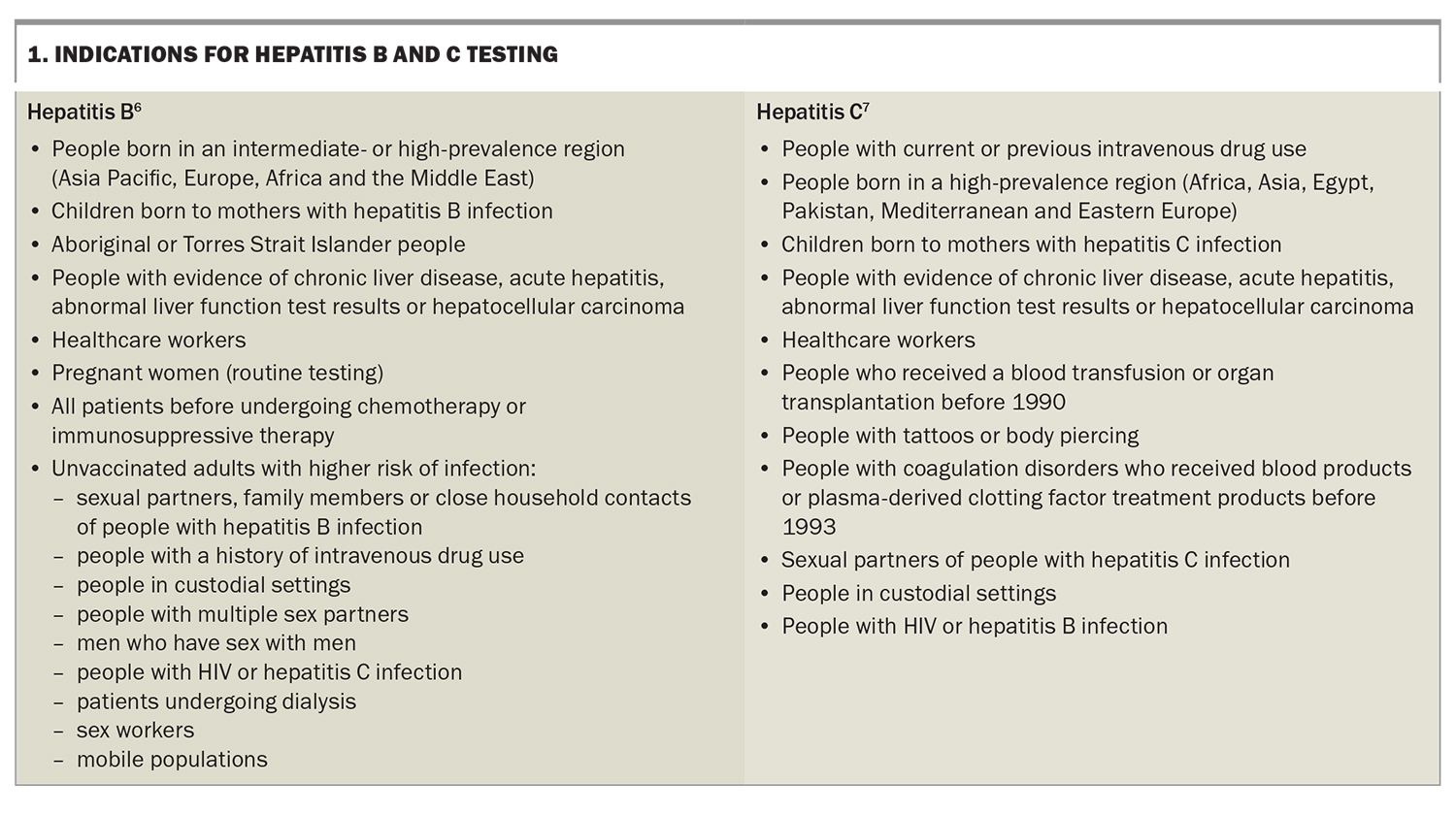

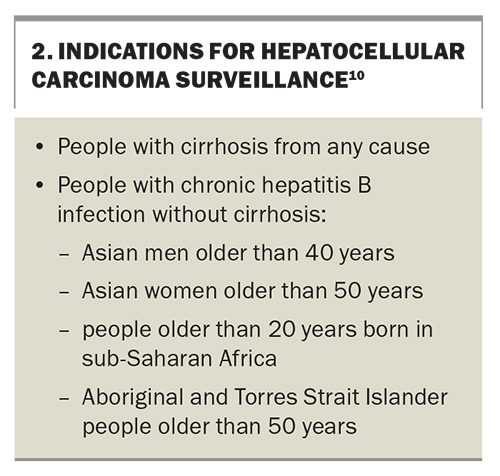

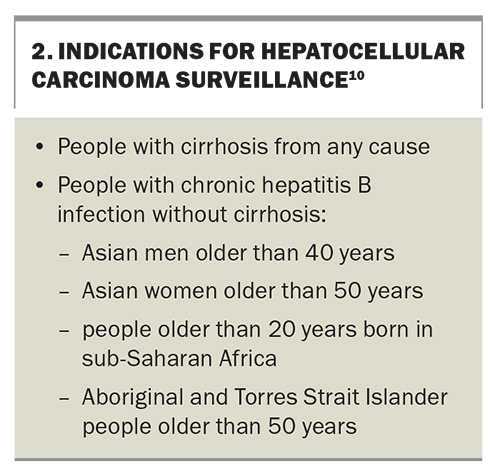

The risk of developing HCC is increased in people with chronic hepatitis B or C infection. Equipping people at high risk of these infections with the knowledge and resources to mitigate risky behaviour is paramount to preventing infection or reinfection. High-risk individuals should be screened with serological testing to identify those with active hepatitis Box 1.6,7 People with hepatitis C should be treated with antiviral therapy, aiming for sustained virological response (cure), as achieving cure confers a significantly lower risk of HCC.8 All people, especially those in high-risk groups (health workers, travellers, injecting drug users and people with multiple sexual partners), should be vaccinated against hepatitis B to prevent infection. Anyone who is positive for hepatitis B surface antigen should have further testing to determine disease stage and be monitored or referred according to treatment guidelines.9 Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection and additional risk factors should undergo regular surveillance for HCC (Box 2).10

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

The recent emergence of MAFLD as a rising cause of HCC has been fuelled by escalating rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome.11 Up to half of MAFLD-related HCC occurs in the absence of cirrhosis, but most of these patients have advanced fibrosis.11,12 Strategies to reduce MAFLD-related HCC include management of diabetes, weight loss and lifestyle interventions, such as physical activity and a healthy diet. As obesity and diabetes are independent risk factors for HCC development, managing these is also beneficial for patients with chronic liver diseases other than MAFLD.13 Bariatric surgery can play a role for patients with severe obesity in whom lifestyle interventions have failed. Chemoprevention strategies, including the use of nonlipophilic statins and aspirin, have been associated with reduced HCC risk in large retrospective studies, but prospective trials are lacking, and these strategies are not currently recommended in guidelines.14

HCC surveillance

Given that early HCC is potentially curable, patients who are at high risk of developing HCC should undergo regular surveillance to enable earlier detection and improved survival.15 Regular surveillance is indicated for all patients with cirrhosis and a reasonable life expectancy and for select noncirrhotic individuals with chronic hepatitis B infection (Box 2). Surveillance should also be considered for patients with chronic hepatitis B infection who have a first-degree relative with HCC.16

The mainstay of HCC surveillance is six-monthly abdominal ultrasound.10 This can be combined with six-monthly testing of serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels. In patients with poor sonographic visualisation (e.g. due to body shape, overlying bowel gas or liver nodularity from fibrosis), multiphase CT or MRI should be used as an alternative modality. As adherence to HCC surveillance is suboptimal, GPs have an important role in ensuring that appropriate patients do undertake regular surveillance (Figure).17

If a solid lesion of 10 mm or larger in size is identified on surveillance, patients should undergo cross-sectional contrast imaging with either multiphase CT or MRI to further characterise the lesion. Lesions smaller than 10 mm can be followed up with a repeat liver ultrasound every three months, until either the lesion grows to at least 10 mm or it appears stable.

Diagnosis and staging

Unlike other cancers, biopsy is not required for a diagnosis of HCC, and a radiological diagnosis can be made with either multiphase CT or MRI.10 A liver lesion with hyperenhancement in the arterial phase and washout in the portal venous or delayed phase is characteristic of HCC in a patient with liver disease. In rare cases where both imaging modalities are inconclusive, a biopsy can provide histological confirmation. All patients with suspected HCC should be referred to a specialist centre for a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting to confirm the diagnosis of HCC and decide on a course of management. As most HCCs occur in people with cirrhosis, and almost all occur in those with chronic liver disease, patients with these conditions should initially be referred to a gastroenterologist or hepatologist.

Once diagnosed, HCC is staged using the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system.18 Based on the patient’s tumour burden, liver function and performance status, the BCLC system classifies HCC into five stages: very early (BCLC-0), early (BCLC-A), intermediate (BCLC-B), advanced (BCLC-C) and terminal (BCLC-D).

Management

Importance of a multidisciplinary approach

The BCLC staging system provides a guide to the recommended treatment for each stage of HCC. However, this recommendation needs to be individualised to each patient’s situation and treating centre. Optimal management of HCC requires an MDT approach, ideally involving gastroenterologists or hepatologists, hepatobiliary and transplant surgeons, diagnostic and interventional radiologists, medical and radiation oncologists, palliative care physicians, liver nurses and administrative staff. A collaborative MDT approach is associated with improved overall survival and is needed to effectively discuss the complexity of each patient’s HCC, taking into account their underlying liver disease and any comorbidities.19 Regular MDT meetings facilitate consensus decision-making about diagnosis and development of personalised treatment plans.

Very early-stage and early-stage disease

In general, curative treatment options can be offered to people with very early- or early-stage HCC. These options include surgical resection, ablation or liver transplantation. Patients with a solitary tumour in the absence of significant liver dysfunction or portal hypertension can be evaluated for surgical resection, which results in good outcomes (five-year survival of 70%).20 Alternatively, tumour ablation is also recommended for patients with very early- or early-stage HCC and small tumours (up to 3 cm in size). Ablation of HCCs can be performed using various methods, including thermal ablation (radiofrequency ablation or microwave ablation) and, infrequently, cryoablation or ethanol injection. For small tumours, thermal ablation and surgery offer similar outcomes, but both techniques are associated with high rates of disease recurrence (up to 80%), usually elsewhere in the liver.21,22 Increasingly, radiotherapy delivered at ablative doses, either by stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) or by radioembolisation of yttrium-90-loaded microspheres, also known as selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT), is being used with curative intent for early-stage disease.23-25

Intermediate-stage disease

The tumour burden in intermediate-stage HCC is heterogeneous, ranging from two tumours (with one larger than 3 cm) up to any number of tumours in the absence of extrahepatic spread or vascular invasion.26 Treatment options are correspondingly varied and can include liver transplantation, locoregional therapies (transarterial chemoembolisation [TACE], SIRT or SBRT) or systemic therapies, depending on the patient and the tumour characteristics. This variation again highlights the need for an MDT approach. Most patients with intermediate-stage HCC undergo TACE, which involves intra-arterial infusion of cytotoxic agents into the branch(es) of the hepatic artery supplying the tumour, followed by embolisation of those same vessels. Although TACE can lead to improved overall survival, it is considered a noncurative option.27

Liver transplantation

Patients with unresectable early- or intermediate-stage HCC should be considered for liver transplantation if their disease is not too extensive (transplant criteria are determined by the size and number of tumours and the patient’s AFP level) and particularly if their disease recurs after previous treatment. Patients with tumour burdens that exceed transplant criteria may still be eligible for transplantation if they are brought back within the criteria after treatment (downstaging).28 However, patients with vascular invasion or extrahepatic metastases are not suitable candidates for transplantation. Patients should also have no medical or psychosocial contraindications to transplantation. Liver transplantation has the advantage of treating both the HCC and the underlying liver disease, which results in excellent long-term outcomes (greater than 75% five-year overall survival and less than 10% recurrence rate).29

Systemic therapies for advanced-stage disease

Advanced-stage HCC is characterised by vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread. Systemic therapy is recommended as first-line treatment for patients with preserved liver function and good functional status. Systemic therapy is also recommended for patients with intermediate-stage disease who have been undergoing locoregional therapy but whose disease has progressed or not responded to this treatment or who are not amenable to locoregional therapy.

There have been substantial recent developments in treatment options for advanced-stage HCC. Sorafenib, an oral multikinase inhibitor, was the first-line treatment for more than a decade, after a landmark 2008 trial showed that it improved overall survival by two to three months compared with placebo.30 In 2018, lenvatinib (another oral multikinase inhibitor) was shown to be noninferior to sorafenib in terms of overall survival but with a threefold higher objective response rate.31 Shortly after this, lenvatinib overtook sorafenib as the preferred agent for treating advanced-stage HCC in Australia.32 Although adverse effects, including hypertension, diarrhoea and a characteristic skin rash (palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia), are common with these multikinase inhibitors, these effects are generally manageable and abate with dose reduction.

As with other cancers, immunotherapy has changed the treatment landscape for advanced-stage HCC.33 In 2020, the intravenous combination of atezolizumab (a checkpoint inhibitor) and bevacizumab (an antiangiogenic drug) was the first regimen to show superiority over sorafenib for advanced-stage HCC.34 This has now become the preferred first-line treatment, while lenvatinib and sorafenib still have a role for patients with intolerance or contraindication to atezolizumab or bevacizumab. Although the oral multikinase inhibitors are more convenient to take, administration of atezolizumab and bevacizumab every three weeks can be facilitated by most oncology units and infusion centres. Another promising regimen is the combination of two checkpoint inhibitors – tremelimumab and durvalumab – which has been shown to significantly improve overall survival compared with sorafenib in patients with unresectable HCC.35 This combination has recently been TGA approved but is not yet subsidised in Australia. These immunotherapy-based regimens can cause immune-related adverse effects in multiple organ systems, while bevacizumab can cause hypertension, proteinuria, delayed wound healing and gastrointestinal bleeding.36 GPs play an important role in identifying and managing patients with adverse effects from their HCC treatment.

Systemic therapies are usually continued until patients develop significant adverse effects (intolerance) or their HCC progresses despite the treatment. For those with disease progression, a lack of evidence means the choice of second-line treatments is not yet clear. This is a focus of active research through clinical trials.

Assessing response to treatment and adverse effects

Patients should be monitored with three-monthly multiphase CT or MRI for the first two years after surgery or locoregional therapy or while receiving systemic therapy. Except for liver transplantation, HCC treatments do not treat the underlying liver disease. Therefore, HCC recurrence, either at the previous treatment site or elsewhere in the liver, is common, and patients often require ongoing review at MDT meetings.

Adverse effects caused by treatment also require regular monitoring with clinical reviews and laboratory tests. Patients with cirrhosis undergoing surgery or locoregional therapies for HCC are at risk of liver decompensation, as nontumour liver tissue is invariably resected or killed during treatment. GPs are well placed to detect adverse effects in patients between their specialist visits and can expedite earlier review (Figure). Furthermore, GPs can help with managing some common adverse effects, such as hypertension from multikinase inhibitors or bevacizumab.

Palliative care

As the overall prognosis of HCC is poor, patients may benefit from early supportive and palliative care.10 Palliative care can reduce physical and psychological symptoms and improve quality of life and healthcare utilisation across all stages of HCC.37 Currently, discussions with patients about palliative care are occurring too late.38 Even in those with advanced- or terminal-stage disease, palliative care referral rates are low (less than 50%), and patients are mostly referred within days of their death.39 Patients with HCC have often had longer relationships with their GPs than with their treating specialists. This makes GPs well suited to have initial conversations about supportive and palliative care and to make a referral where appropriate, especially for those with incurable disease (Figure).

Conclusion

The epidemiology and management of HCC are evolving. GPs play a vital role in combating the increasing HCC burden in Australia. This role begins before HCC is diagnosed, with disease prevention, early detection of cirrhosis and regular surveillance of high-risk individuals. In patients with suspected HCC, timely referral to specialists for discussion at an MDT meeting is crucial to determine the most appropriate treatment. Even after treatment is administered, GPs continue to play a complementary role in monitoring patients with HCC alongside the treating specialists. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer data in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2022. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/health-conditions-disability-deaths/cancer/data?&page=4 (accessed July 2023).

2. Yu XQ, Feletto E, Smith MA, Yuill S, Baade PD. Cancer incidence in migrants in Australia: patterns of three infection-related cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2022; 31: 1394-1401.

3. Díaz-González Á, Forner A. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 30: 1001-1010.

4. Jacob R, Prince DS, Kench C, Liu K. Alcohol and its associated liver carcinogenesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023 Jun 1. doi: 10.1111/jgh.16248. Online ahead of print.

5. Xu X-L, Jiang L-S, Wu C-S, et al. The role of fibrosis index FIB-4 in predicting liver fibrosis stage and clinical prognosis: a diagnostic or screening tool? J Formos Med Assoc 2022; 121: 454-466.

6. Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine. Testing portal. Sydney: ASHM; 2023. Available online at: https://testingportal.ashm.org.au/national-hbv-testing-policy/indications-for-hbv-testing (accessed July 2023).

7. Hepatitis C Virus Infection Consensus Statement Working Group. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection: a consensus statement (2022). Melbourne: Gastroenterological Society of Australia; 2022.

8. El‐Serag HB, Kanwal F, Richardson P, Kramer J. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after sustained virological response in veterans with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2016; 64: 130-137.

9. Lubel JS, Strasser SI, Thompson AJ, et al. Australian consensus recommendations for the management of hepatitis B. Med J Aust 2022; 216: 478-486.

10. Lubel JS, Roberts SK, Strasser SI, et al. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a consensus statement. Med J Aust 2021; 214: 475-483.

11. Pugliese N, Alfarone L, Arcari I, et al. Clinical features and management issues of NAFLD-related HCC: what we know so far. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023; 17: 31-43.

12. Behari J, Gougol A, Wang R, et al. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease without cirrhosis or advanced liver fibrosis. Hepatol Commun 2023; 7: e00183.

13. Liu K, McCaughan GW. Epidemiology and etiologic associations of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and associated HCC. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018; 1061: 3-18.

14. Li S, Saviano A, Erstad DJ, et al. Risk factors, pathogenesis, and strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma prevention: emphasis on secondary prevention and its translational challenges. J Clin Med 2020; 9: 3817.

15. Cancer Council Australia. Clinical practice guidelines for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance for people at high risk in Australia. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia; 2023.

16. Cancer Council Australia. Roadmap to liver cancer control in Australia. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia; 2023.

17. Zhao C, Jin M, Le RH, et al. Poor adherence to hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of a complex issue. Liver Int 2018; 38: 503-514.

18. Llovet JM, Fuster J, Bruix J. The Barcelona approach: diagnosis, staging, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2004; 10 (2 Suppl 1): S115-S120.

19. Agarwal PD, Phillips P, Hillman L, et al. Multidisciplinary management of hepatocellular carcinoma improves access to therapy and patient survival. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51: 845-849.

20. Poon RT-P, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Wong J. Long-term survival and pattern of recurrence after resection of small hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with preserved liver function: implications for a strategy of salvage transplantation. Ann Surg 2002; 235: 373-382.

21. Majumdar A, Roccarina D, Thorburn D, Davidson BR, Tsochatzis E, Gurusamy KS. Management of people with early‐or very early‐stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017 (3): CD011650.

22. Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, Salem R, Saborowski A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2022; 400: 1345-1362.

23. Mathew AS, Dawson LA. Current understanding of ablative radiation therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2021; 8: 575-586.

24. Kim E, Sher A, Abboud G, et al. Radiation segmentectomy for curative intent of unresectable very early to early stage hepatocellular carcinoma (RASER): a single-centre, single-arm study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 7: 843-850.

25. Prince DS, Schlaphoff G, Davison SA, et al. Selective internal radiation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a 15-year multicenter Australian cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 37: 2173-2181.

26. Prince D, Liu K, Xu W, et al. Management of patients with intermediate stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2020; 12: 1758835920970840.

27. Liu K, Zhang X, Xu W, et al. Targeting the vasculature in hepatocellular carcinoma treatment: starving versus normalizing blood supply. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2017; 8(6): e98.

28. Liu K, McCaughan GW. How to select the appropriate "neoadjuvant therapy" for hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018; 19: 1167-1170.

29. Dennis C, Prince DS, Moayed-Alaei L, et al. Association between vessels that encapsulate tumour clusters vascular pattern and hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence following liver transplantation. Front Oncol 2022; 12: 997093.

30. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 378-390.

31. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018; 391: 1163-1173.

32. Patwala K, Prince DS, Celermajer Y, et al. Lenvatinib for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma—a real-world multicenter Australian cohort study. Hepatol Int 2022; 16: 1170-1178.

33. Xu W, Liu K, Chen M, et al. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advances and future perspectives. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2019; 11: 1758835919862692.

34. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1894-1905.

35. Abou-Alfa GK, Lau G, Kudo M, et al. Tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. NEJM Evid 2022; 1: EVIDoa2100070.

36. Remash D, Prince DS, McKenzie C, Strasser SI, Kao S, Liu K. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hepatotoxicity: a review. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27: 5376-5391.

37. Laube R, Sabih AH, Strasser SI, Lim L, Cigolini M, Liu K. Palliative care in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 36: 618-628.

38. Sabih AH, Laube R, Strasser SI, Lim L, Cigolini M, Liu K. Palliative medicine referrals for hepatocellular carcinoma: a national survey of gastroenterologists. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021 Mar 18. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002807. Online ahead of print.

39. Bonnichsen M, Liu K, Powter E, Majumdar A, Strasser S, McCaughan G. Palliative care referrals for advanced stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Proceedings of The Liver Meeting; 2019 Nov 8-12; Boston, USA.