A widespread erythematous targetoid eruption

Test your diagnostic skills in our regular dermatology quiz. What is the cause of these asymptomatic lesions?

Case presentation

A 16-year-old girl presents with a widespread skin eruption of sudden onset. The lesions are asymptomatic but the eruption was preceded by a flu-like illness (fevers, chills, malaise) by one day. The patient does not have any medical history of note. She does not take regular prescription medications, denies using any over-the-counter preparations, and has not had any recent vaccinations.

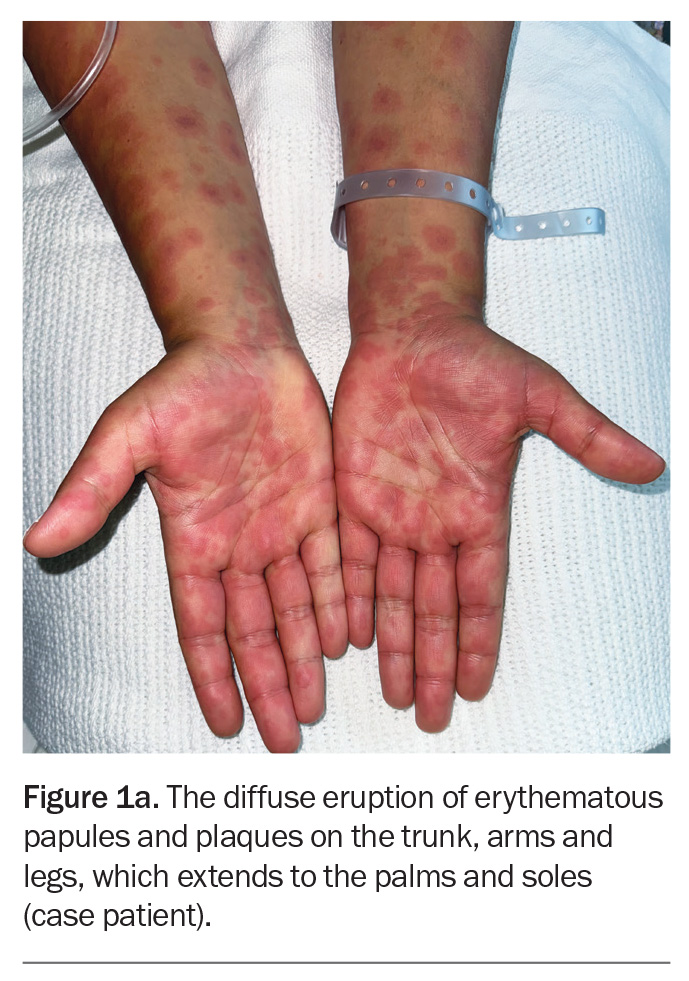

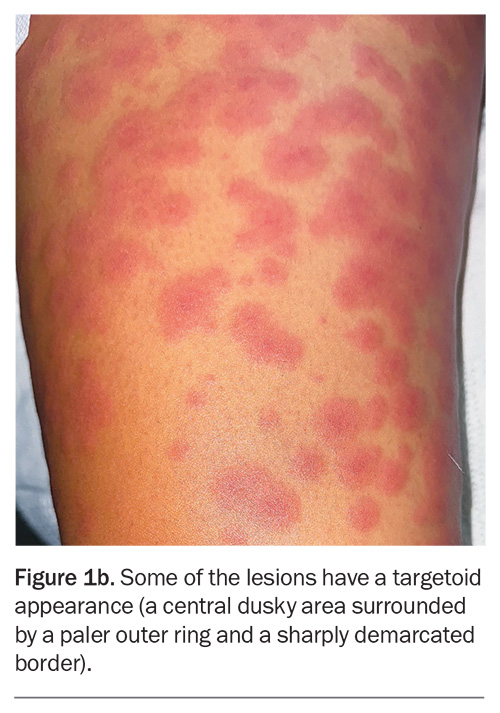

On examination, raised, erythematous papules coalescing into plaques are observed on the patient’s trunk, arms and legs (Figure 1a). The eruption extends bilaterally to the palms, soles and vulval skin but the oral and ocular mucosal surfaces are not involved. The lesions are noted to blanch with pressure. On closer inspection, some of the lesions look like ‘targets’, with a central dusky area surrounded by a paler outer ring and sharply demarcated border (Figure 1b).

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Viral exanthems

Viral exanthems, a common presentation in both children and adults, are widespread eruptions that accompany viral infections. Viral exanthems may be triggered directly by a viral infection itself or indirectly, such as by a hypersensitivity reaction to the virus.1

Certain exanthems may be diagnosed on the basis of their distinctive morphology, including chickenpox (varicella-zoster virus), measles (measles virus), rubella (rubella virus), roseola (human herpes virus types 6 and 7), erythema infectiosum (parvovirus B19) and hand, foot and mouth disease (coxsackievirus). However, viral exanthems often present nonspecifically and can be a diagnostic challenge.2 Helpful clues when evaluating patients include associated systemic symptoms, immunisation history and contact with infected or unwell individuals.3

In general, viral exanthems are self-limiting and treatment is supportive. It is more important to make a definitive diagnosis in pregnant women and immunocompromised or unvaccinated people, as well as in children who may have been exposed to such groups.4

For the case patient, her history of systemic symptoms preceding the rash make a viral exanthem a top differential diagnosis. However, the targetoid appearance of the lesions may point to an alternative diagnosis.

Urticaria

Urticaria (‘hives’) is characterised by an eruption of pruritic lesions that may be localised or widespread. It is often polymorphic and usually includes wheals (raised, oedematous plaques with a skin-coloured or pale centre surrounded by an area of erythema). These lesions are typically transient and migratory, disappearing from one location before reappearing elsewhere, so changes in the shape and distribution of the rash over time is one of the keys to the diagnosis.5 The condition is caused by activation of cutaneous mast cells, which release chemical mediators, predominantly histamine, that increase vascular permeability in the surrounding tissue and cause the typical oedematous appearance of urticarial lesions.6

Urticaria may be classified as acute (less than six weeks duration, often lasting hours to days) or chronic (more than six weeks duration). Most cases of acute urticaria are idiopathic. However, there are many known triggers, including:

- viral or bacterial infections

- allergy to foods or medications

- contact or irritant dermatitis

- vaccination

- insect bites and stings.

Acute urticaria is not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, whose eruption had a fixed distribution.

Sweet syndrome

Sweet syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) is an uncommon skin disorder associated with fever and other systemic symptoms, including malaise, arthralgia, myalgia and headache. Other organs may also be affected, most commonly the eyes, where it may manifest as conjunctivitis or episcleritis.7

Sweet syndrome most commonly occurs in middle-aged women but other population groups may be affected. The cause is not completely understood, but studies have shown that it is often triggered by an insult to the immune system, such as an acute systemic infection, malignancy (particularly haematological malignancy) or drug exposure. Susceptibility is increased in people with an underlying chronic condition or immunodeficiency.8

The skin rash of Sweet syndrome has a sudden onset and appears as widespread, erythematous vesicles, papules, nodules and/or plaques, typically distributed on the neck and limbs. The lesions may be small initially but tend to grow and may coalesce to form larger, irregular plaques. They are characteristically painful and tender and may last for days to weeks.9

Sweet syndrome may be diagnosed clinically but is usually confirmed with skin biopsy. Given the disease associations, further investigations for underlying malignancy or autoimmune conditions are usually recommended, with the choice of these made with consideration of each patient’s demographic and risk factors.10

Sweet syndrome is not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, whose rash was not painful or tender. The lesions of Sweet syndrome tend to be juicy in appearance. Additionally, the patient is not within the age group that is most commonly affected.

Erythema multiforme

This is the correct diagnosis. Erythema multiforme is an immune-mediated skin disorder that presents as a symmetrical, erythematous eruption. Its characteristic targetoid lesions have concentric rings of colour variation: a central darker area, surrounding pale ring, and sharply demarcated border. The eruption may be widespread and typically includes the palms and soles. Erythema multiforme is classified as minor (affecting the skin only) and major (also involving oral, urogenital or, rarely, ocular mucosa).11 The mucosal lesions may present as blisters, which can burst to form painful erosions. Patients are typically aged 20 to 30 years.

About 90% of cases of erythema multiforme are associated with infections, with herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) the most common.12 The presence of herpes labialis (‘cold sore’), either preceding or occurring together with the eruption, may be a useful clue to this precipitant. Other infectious triggers include Mycoplasma pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus and influenza virus. An infectious cause may be suspected in patients who report a prodrome of systemic symptoms including fever, malaise and myalgia. Noninfectious causes include medications (e.g. antibiotics, antiepileptics, NSAIDs), vaccines, pregnancy and coexisting conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and malignancy.13-15 However, in many cases the cause remains unknown.

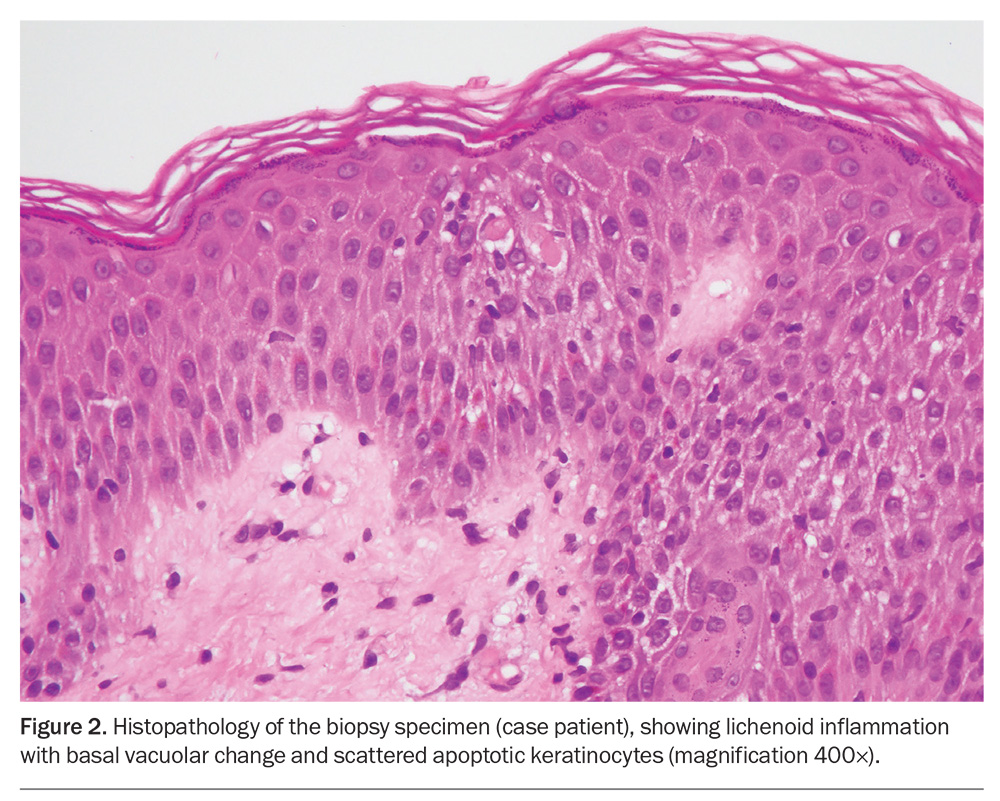

A diagnosis of erythema multiforme is usually made clinically. Serological testing for infectious causes is sometimes performed, which can help to direct treatment. When there is doubt about the diagnosis, a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out more serious conditions such as autoimmune blistering diseases, namely bullous pemphigoid.12 The histopathological findings of erythema multiforme include apoptotic keratinocytes, basal vacuolar change, spongiosis, epithelial necrosis and, sometimes, blisters.16

Management

Mild and uncomplicated cases of erythema multiforme are typically self-limiting and resolve within four to six weeks. Supportive treatment includes oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids or a short course of oral prednisone to alleviate pruritus and discomfort. Oral mucosal lesions may be painful and can be treated with oral antiseptic mouthwashes and topical corticosteroids.17 The use of all potential inciting medications should be stopped.

If HSV infection is suspected to be the cause then oral antiviral therapy should be given early to reduce the severity and duration of the rash.18 Treatment options are aciclovir (400 mg five times daily for seven days), famciclovir (500 mg twice daily for seven days) or valaciclovir (1 g twice daily for seven days).19 If Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection is suspected then appropriate antibiotic therapy is warranted.

In patients with recurrent erythema multiforme that is HSV-associated or idiopathic, antiviral prophylaxis has been shown to be effective in reducing the frequency and severity of episodes.20 Current treatment recommendations include aciclovir (400 mg twice daily), famciclovir (250 mg twice daily) or valaciclovir (500 mg twice daily), for six months or more.12 In patients who respond, the duration of continuous antiviral therapy may be extended.12

For patients with erythema multiforme major, the spectrum of severity is wide. For those who have extensive and severe oral mucosal involvement, oral intake may be affected and admission to hospital may be appropriate for close monitoring and parenteral rehydration.11 For patients with eye involvement (rare), early consultation with an ophthalmologist for assessment and management is crucial to prevent long-term complications.21

Outcome

The case patient was given a provisional diagnosis of erythema multiforme. Because of her young age and the extensive nature of the eruption, a punch biopsy was performed; the histological findings confirmed the diagnosis (Figure 2). Serological testing, including a viral panel, was performed but did not reveal an infectious precipitant. A clear cause for erythema multiforme was not identified.

The patient was treated supportively with betamethasone dipropionate (0.05% ointment applied twice daily for seven to 10 days) and loratadine (10 mg as needed) to alleviate pruritus. At a follow-up visit one month later, her rash had cleared with only a few areas of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation remaining. She was advised to present to her GP if she experiences a similar episode in the future. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Scott LA, Stone MS. Viral exanthems. Dermatol Online J 2003; 9: 4.

2. Keighley CL, Saunderson RB, Kok J, Dwyer DE. Viral exanthems. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2015; 28: 139-150.

3. Fölster‐Holst R, Kreth HW. Viral exanthems in childhood – infectious (direct) exanthems. Part 1: classic exanthems. JDDG: J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2009; 7: 309-316.

4. Biesbroeck L, Sidbury R. Viral exanthems: an update. Dermatol Ther 2013; 26: 433-438.

5. Kolkhir P, Giménez-Arnau AM, Kulthanan K, Peter J, Metz M, Maurer M. Urticaria. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2022; 8: 61.

6. Church MK, Kolkhir P, Metz M, Maurer M. The role and relevance of mast cells in urticaria. Immunol Rev 2018; 282: 232-247.

7. Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol 2003; 42: 761-778.

8. Maalouf D, Battistella M, Bouaziz J-D. Neutrophilic dermatosis: disease mechanism and treatment. Curr Opin Hematol 2015; 22: 23-29.

9. Casarin Costa JR, Virgens AR, et al. Sweet syndrome: clinical features, histopathology, and associations of 83 cases. J Cutan Med Surg 2017; 21: 211-216.

10. Joshi TP, Friske SK, Hsiou DA, Duvic M. New practical aspects of Sweet syndrome. Am J Clin Dermatol 2022; 23: 301-318.

11. Trayes KP, Love G, Studdiford JS. Erythema multiforme: recognition and management. Am Fam Physician 2019; 100: 82-88.

12. Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of erythema multiforme: a review for the practicing dermatologist. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51: 889-902.

13. Katoulis AC, Liakou A, Bozi E, et al. Erythema multiforme following vaccination for human papillomavirus. Dermatology 2010; 220: 60-62.

14. Goeteyn V, Naeyaert JM, Lambert J, Monbaliu L, Vermander F. Is systemic autoimmune disease a risk factor for terbinafine‐induced erythema multiforme? Br J Dermatol 2000; 142: 578-579.

15. Moravvej H, Razavi GM, Farshchian M, Malekzadeh R. Cutaneous manifestations in 404 Iranian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008; 74: 607-610.

16. Bedi TR, Pinkus H. Histopathological spectrum of erythema multiforme. Br J Dermatol 1976; 95: 243-250.

17. Soares A, Sokumbi O. Recent updates in the treatment of erythema multiforme. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021; 57: 921.

18. Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ. In: Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine. Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, et al, eds. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

19. Therapeutic Guidelines. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd. Available online at: www.tg.org.au (accessed March 2024).

20. Schofield JK, Tatnall FM, Leigh IM. Recurrent erythema multiforme: clinical features and treatment in a large series of patients. Br J Dermatol 1993; 128: 542-545.

21. Chang YS, Huang FC, Tseng SH, Hsu CK, Ho CL, Sheu HM. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis: acute ocular manifestations, causes, and management. Cornea 2007; 26: 123-129.