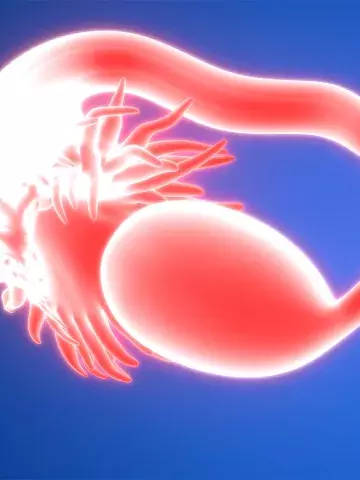

Premature ovarian insufficiency may increase severe autoimmune disease risk

By Rebecca Jenkins

Autoimmune conditions are two to three times more common in women with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) compared with controls and often precede the POI diagnosis, a large data-linkage study finds.

The population-based registry study, published in Human Reproduction, included 3972 women diagnosed with spontaneous POI between 1988 and 2017 and 15,708 female population controls.

Women with POI were identified from the reimbursement registry of the Finnish Social Insurance Institution by their right to hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and autoimmune disease diagnoses were evaluated using hospital records from 1970 until the end of 2017.

Researchers found that at the time of being diagnosed with POI, the group of women with POI were two to three times more likely to have at least one severe autoimmune disease compared with the control group of similarly aged women from the general population.

The incidence of these autoimmune diseases was also two- to threefold higher during the first years after being diagnosed with POI, compared with the control group, and incidence remained higher than in the control group even a decade after being diagnosed with POI.

Compared with controls, women with POI had an increased prevalence of several specific autoimmune diseases before being diagnosed, with the highest risk found for polyglandular autoimmune diseases (odds ratio [OR], 25.8) and Addison’s disease (OR, 22.9).

They also had an increased risk of vasculitis (OR, 10.2), systemic lupus erythematosus (OR, 6.3), rheumatoid arthritis (OR, 2.3), sarcoidosis (OR, 2.3), inflammatory bowel diseases (OR, 2.2) and hyperthyroidism (OR, 1.9) before being diagnosed with POI.

Clinical Associate Professor Amanda Vincent, Head of Early Menopause Research at the Monash Centre for Health Research and Implementation, Monash University, Melbourne, said clinicians and women with autoimmune diseases needed to be aware that severe autoimmune disease might be diagnosed before or after POI diagnosis.

Of note, Professor Vincent said the study found Addison’s disease was diagnosed in 0.6% of women with POI before POI diagnosis and 0.5% of women after POI diagnosis.

‘This is in contrast to previous studies which indicated that POI commonly precedes adrenal insufficiency,’ she told Medicine Today.

It was known that there was a genetic association between POI and autoimmune polyglandular syndrome, she said, which explained the high likelihood of women with POI having the condition.

However, the finding regarding sarcoidosis was a novel association with POI.

‘Women under age 40 years with the associated autoimmune diseases should be aware of the symptoms and signs of POI and see their doctor if they occur,’ Professor Vincent said.

Symptoms and signs included irregular menstrual periods or no periods at all for at least four months and/or the onset of menopausal symptoms such as hot flushes, she noted; however, hormonal contraception might mask them.

‘Women of reproductive age who are diagnosed with these autoimmune diseases might wish to take the possibility of POI into account when planning a family and seek advice about fertility preservation,’ Professor Vincent added.

Hum Reprod 2024; 39: 2601-2607; doi: 10.1093/humrep/deae213.