INOCA and MINOCA: coronary vasomotor disorders in clinical practice

Many patients with angina and/or myocardial infarction do not have obstructive coronary artery disease. Clinicians’ awareness of ischaemia with no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA) and myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA) may help such patients who have ongoing chest symptoms after a ‘normal’ angiogram.

- Angina or myocardial infarction may occur in patients with no obstructive coronary stenosis.

- Ischaemia with non-obstructed coronary arteries (INOCA) can be caused by coronary microvascular dysfunction and/or coronary vasospasm.

- The differential diagnoses for myocardial infarction with non-obstructed coronary arteries (MINOCA) include coronary plaque disruption, vasospasm, spontaneous coronary thrombosis or embolism, and myocarditis, among others.

- Coronary angiography and CT coronary angiography are not able to detect vasomotor disorders; hence, these conditions are often under-recognised.

- INOCA and MINOCA should be suspected in patients with persistent ischaemic chest pain without a clear cause; subspecialist referral to physicians with expertise in invasive testing for angina may be helpful.

- Patients with INOCA and MINOCA may be at risk of major adverse cardiac events, making GP awareness of vasomotor disorders crucial for delivering optimal preventive therapy and risk factor management.

Up to half of patients with angina who are referred for invasive coronary angiography have non-obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD).1 These patients may return to their GP with a diagnosis of ‘noncardiac chest pain’, representing an ongoing diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. However, many of these patients have an underlying ischaemic aetiology for their pain and disorders of coronary vasomotion may be relevant. Ischaemia with non-obstructed coronary arteries (INOCA) and myocardial infarction with non-obstructed coronary arteries (MINOCA) are not typically diagnosed during routine coronary angiography. As a result, they represent an important cause of chest symptoms that are typically under-recognised or misdiagnosed, despite their association with morbidity, impaired quality of life and future healthcare resource use.

INOCA is an umbrella term encompassing two major coronary vasomotor disorders that may cause ischaemia without obstructive CAD: coronary microvascular dysfunction, coronary vasospasm or both. This article aims to improve awareness of INOCA and MINOCA by providing an overview of their pathophysiology and outlines how specialist input can help with diagnosis and management.

How can ischaemia or myocardial infarction develop without blocked arteries?

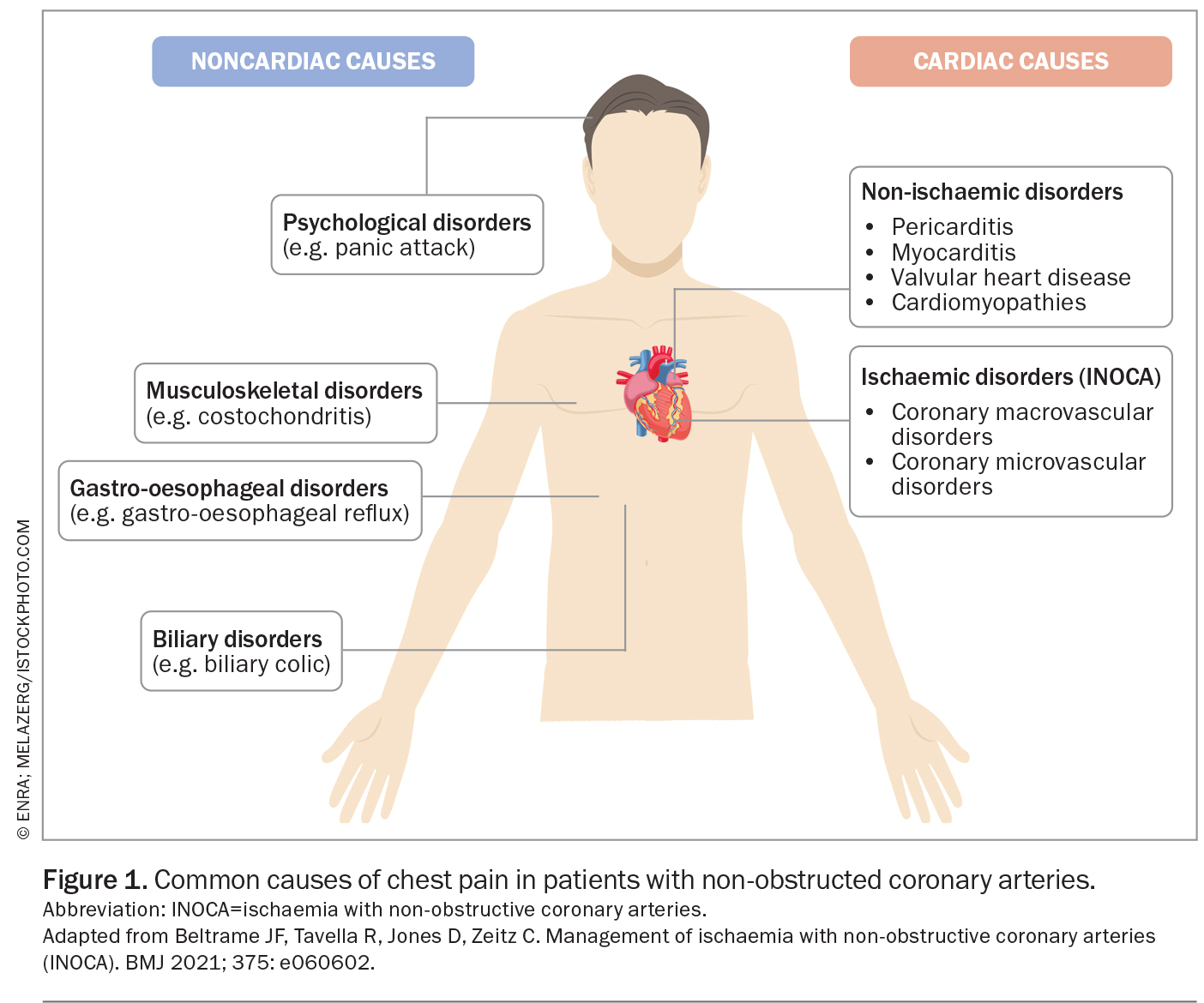

The diagnosis of chest pain in patients with non-obstructive coronary arteries requires a consideration of cardiac and noncardiac causes (Figure 1). Ischaemic disorders typically occur because of a mismatch between myocardial oxygen supply and demand. This can occur in patients with or without obstructive CAD. Coronary microvascular dysfunction or a propensity to epicardial artery spasm may drive ischaemic coronary syndromes. These syndromes can be divided by anatomy into pathophysiological mechanisms (Figure 1).

Vasospasm

Vasospastic angina (VSA), formally known as ‘Prinzmetal’s angina’, is typically described as recurrent glyceryl trinitrate (GTN)-responsive ischaemic chest pain. It often presents with diurnal variation and early morning preponderance of symptoms. Prinzmetal variant angina is the rarer subtype, typically with the worst prognosis, driven by transient focal (or multivessel) occlusive proximal large coronary artery spasm. It is often seen in young smokers with characteristic episodic ST segment elevation during attacks that occur predominantly at rest.2 Spontaneous myocardial infarction, ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death may result. Notably, the more common form of VSA is distinct: distal, diffuse subtotal epicardial vasospasm and characterised by ST segment depression, which may occur during physical exertion. Diurnal variation is seen in both types, with early morning episodes being common.

Coronary microvascular dysfunction

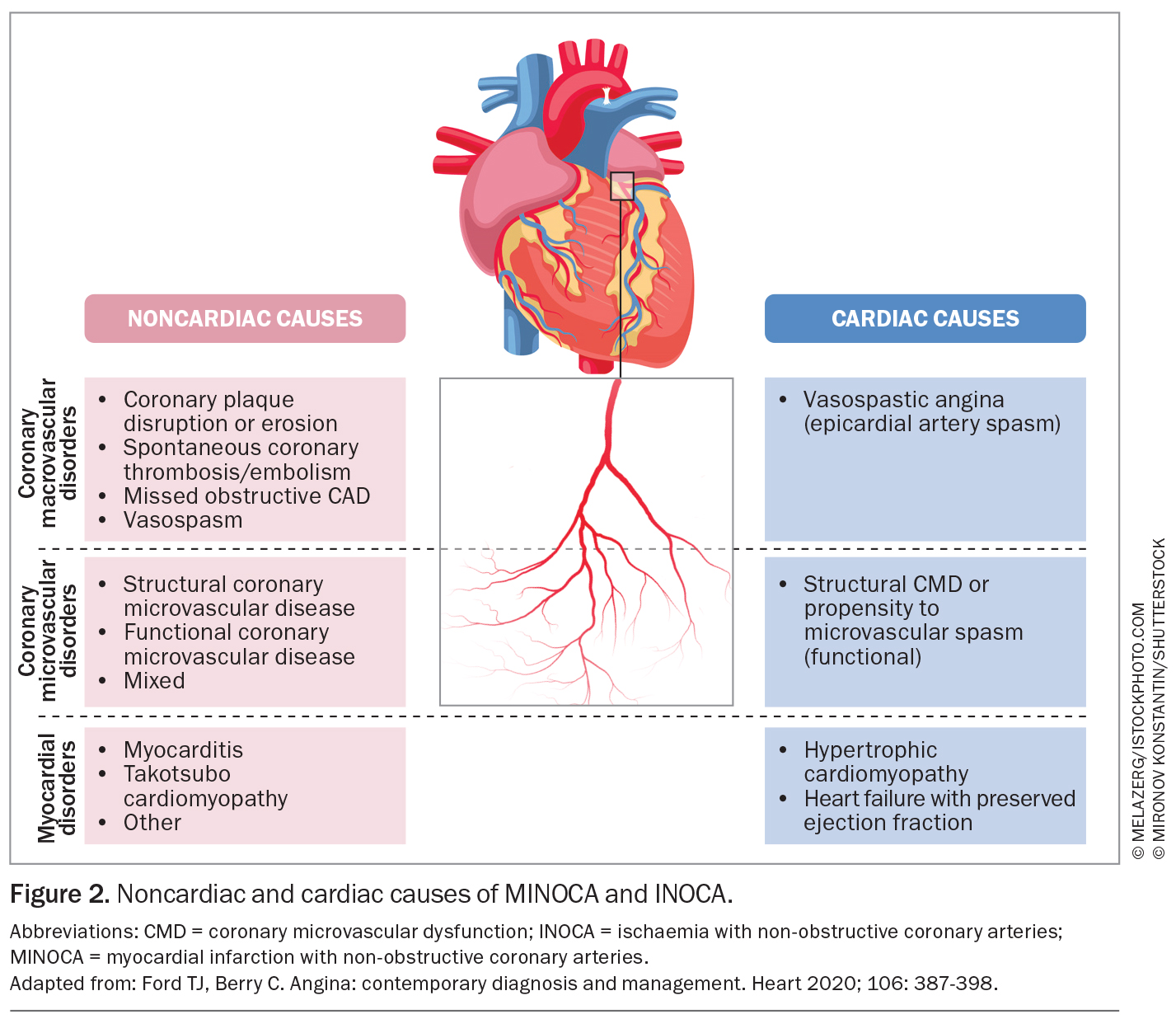

The pathophysiology of coronary microvascular dysfunction is complex. It involves factors including structural abnormalities, variations in resting microvascular tone, propensity to microvascular spasm or inadequate microvascular dilation in response to increased myocardial oxygen demand (functional coronary microvascular dysfunction; Figure 2).3

Mixed

Coronary microvascular dysfunction may also be found in patients with coronary spasm and these patients may have a worse prognosis.4 Myocardial ischaemia caused by epicardial artery spasm or coronary microvascular dysfunction is only one of many potential factors that may contribute to a patient’s symptoms of angina. Other important considerations include the presence of coexisting pathologies or psychological factors, which are common and may be compounded by prolonged diagnostic uncertainty. Patients may also present with angina despite having normal microvascular function, likely because of altered pain perception and nociceptive changes. Importantly, patients with non-anginal chest pain may undergo evaluation for other potential causes, but testing for vasomotor disorders is not indicated for noncardiac pain.

Myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA)

MINOCA accounts for up to 10% of myocardial infarction presentations, presenting clinically as an ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). MINOCA should be thought of as an umbrella term with diverse underlying pathophysiology including coronary and noncoronary causes (Figure 2).

MINOCA refers specifically to myocardial infarction caused by coronary-related issues (e.g. coronary spasm, thrombosis, plaque disruption) without significant coronary artery obstruction. MINOCA mimics (e.g. myocarditis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy) present similarly but have non-coronary causes and are thus excluded from the diagnosis of MINOCA in the latest guidelines.

MINOCA has a more favourable 12-month all-cause mortality compared with ischaemia from obstructive CAD. However, it is associated with considerable morbidity, including the risk of recurrence and hospitalisation. The causes of MINOCA are well defined; therefore, recent international guidelines suggest identification of the underlying cause to provide tailored therapy.5

Clinical presentation and risk factors

Patients with INOCA typically present similarly to patients with obstructive CAD: with angina (typical or atypical) or angina-equivalent symptoms. Although INOCA shares common cardiovascular risk factors with obstructive CAD (e.g. smoking, hypertension and dyslipidaemia), unlike obstructive CAD, it is more prevalent in women and in younger patients.6,7 INOCA has also been linked to systemic inflammatory disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, even in the absence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.8,9 Additionally, INOCA is linked to psychosocial stress, adding complexity to its diagnosis and management.10

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of INOCA first relies on the treating medical practitioner having a high index of clinical suspicion and excluding alternative causes for chest pain (Figure 1), followed by a referral, ideally to a physician or centre with expertise in the diagnosis of vasomotor disorders. Noninvasive stress testing lacks sensitivity for the diagnosis of coronary microvascular dysfunction – a ‘negative’ stress test cannot be used to rule out INOCA from microvascular dysfunction.11

Coronary angiography is performed to exclude obstructive CAD (including assessment for functionally obstructive lesions), followed by invasive functional angiographic testing – the gold standard for the diagnosis of coronary vasomotor disorders. Testing is rarely performed during routine clinical practice in Australia, which may be associated with a lack of subspecialist training and funding (there is no standardised Medicare item number). In addition, physicians may be concerned about procedural safety and the time required. Historically, a reluctance to perform invasive functional angiographic testing may also stem from clinicians’ scepticism about the diagnosis of ischaemic syndromes without obstructive CAD, particularly given the perceived lack of treatment options.

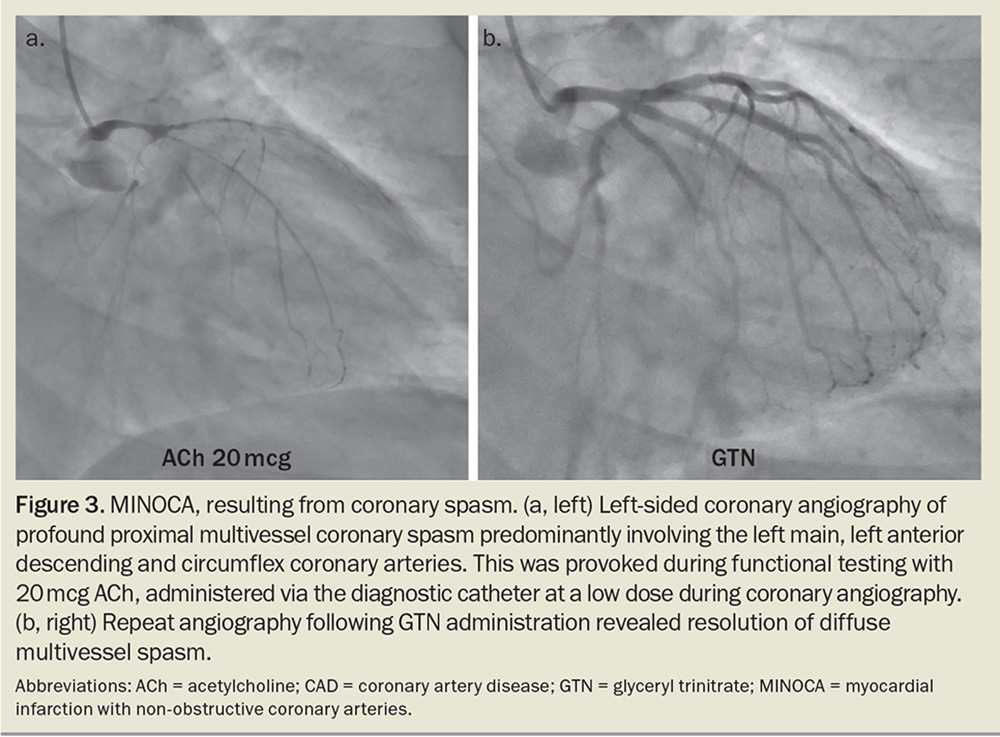

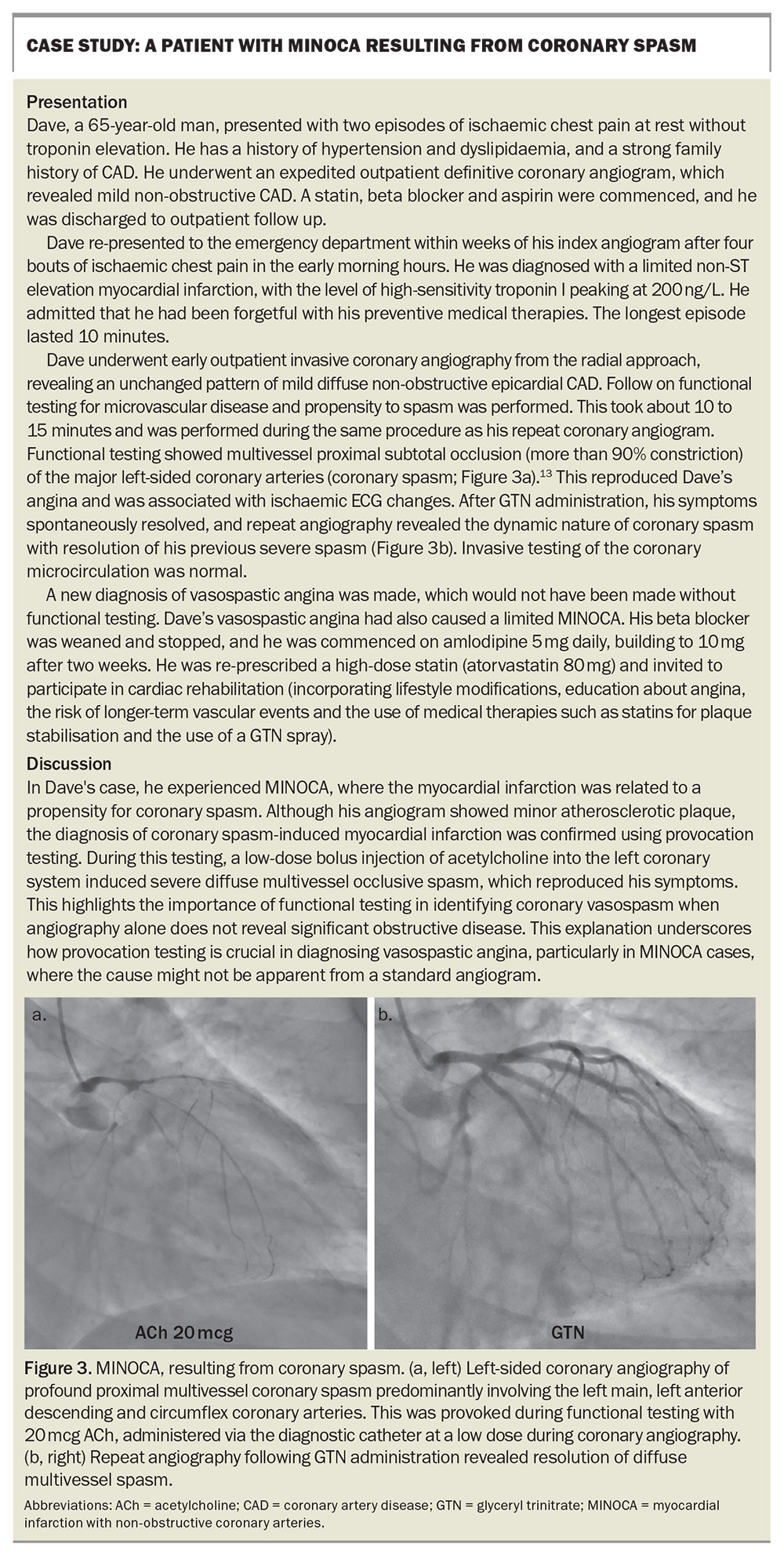

During functional testing, coronary microvascular dysfunction is assessed by measuring coronary blood flow in response to adenosine, a potent vasodilator. The presence of inducible coronary artery spasm is assessed by provocative spasm testing with intracoronary acetylcholine (Figure 3). Typically, this takes a skilled interventional cardiologist no more than 20 minutes and allows confirmation of the diagnosis of INOCA according to standardised criteria, as well as the identification of the INOCA subtype.12

Testing has been evaluated in a randomised controlled trial, showing evidence of safety as well as improved patient health-related quality of life.15 The Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand Coronary Vasomotor Dysfunction Working Group, chaired by Professor John Beltrame, recently completed a consensus statement and protocol to help improve standardised assessment for INOCA and MINOCA using functional coronary angiography.

A case example of a patient with INOCA and MINOCA is presented in the Box.

Prognosis

Patients with stable coronary syndromes, including INOCA, have elevated risks of major adverse cardiovascular events (including death, nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke, and hospitalisation for heart failure or angina), compared with the general population. This elevated risk is not reflected in standard cardiovascular risk assessment tools. Beyond physical morbidity, these patients experience significant psychosocial distress, a compromised quality of life and increased healthcare resource use, primarily because of persistent, undiagnosed symptoms.

Most cardiologists would agree that coronary vasomotor disorders are important to identify in patients with ongoing symptoms. Importantly, the biggest driver of cardiac events is the large burden of atherosclerotic plaque, irrespective of the presence of luminal obstruction; hence, patients with INOCA, but with diffuse coronary artery atherosclerosis, require consideration of disease-modifying therapies, including statins and ACE inhibitors.14

Treatment: personalised care

Once the treatable disorder of coronary vasomotion is determined using invasive functional evaluation, treatment is tailored to the underlying cause with the aim of reducing longer-term cardiovascular risk, in addition to anti-ischaemic therapies aimed at reducing angina burden.

Nonpharmacological measures are fundamental in the management of INOCA. Participation in a cardiovascular rehabilitation program is invaluable for improving cardiovascular fitness and helping patient illness understanding, as well as for education and the alleviation of the psychosocial distress associated with a new diagnosis of heart disease.

Individualised pharmacological treatment has been shown to be more effective in alleviating angina symptoms compared with standard care.15 For vasospastic angina, this may involve the use of calcium channel blockers (e.g. amlodipine or diltiazem) and long-acting nitrates. The management of coronary microvascular disorders is complex because of the diverse pathophysiological mechanisms and varies depending on the subtype. Typically, selective beta blockers are the first-line treatment for coronary microvascular dysfunction (e.g. bisoprolol), but calcium channel blockers may also be tried. Importantly, in patients with predominantly coronary microvascular dysfunction (microvascular angina), nitrates may be detrimental and associated with a reduced exercise capacity and worsening of symptoms, which may be related to nitrate tolerance and steal phenomena. There is an ongoing need for the development of targeted therapies for coronary microvascular dysfunction.

Conclusion

Ischaemic coronary syndromes frequently occur without obstructive epicardial CAD. Microvascular or vasospastic angina may be responsible for ongoing chest pain in patients after a ‘negative’ angiogram, leading to missed diagnosis and suboptimal patient care. Increased awareness, early detection and appropriate referral by GPs for patients with persistent ischaemic chest pain has the potential to improve the quality of life for these patients. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Ford has received payment for proctoring, teaching and lectures from Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific; and has acted as a consultant or speaker for Abbott Vascular, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Bio-Excek and Novartis. Dr Easey and Dr Redwood: None.

References

1. Ford TJ, Yii E, Sidik N, et al. Ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: prevalence and correlates of coronary vasomotion disorders. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2019; 12: e008126.

2. Ford TJ, Berry C. Angina: contemporary diagnosis and management. Heart 2020; 106: 387-398.

3. Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Buchthal SD, et al. Prognosis in women with myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary disease: results from the National Institutes of Health – National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored women’s ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE). Circulation 2004; 109: 2993-2999.

4. Nishimiya K, Suda A, Fukui K, et al. Prognostic links between OCT-delineated coronary morphologies and coronary functional abnormalities in patients with INOCA. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2021; 14: 606-618.

5. Pasupathy S, Air T, Dreyer RP, Tavella R, Beltrame JF. Systematic review of patients presenting with suspected myocardial infarction and nonobstructive coronary arteries. Circulation 2015; 131: 861-870.

6. Shaw LJ, Merz CNB, Pepine CJ, et al. The economic burden of angina in women with suspected ischemic heart disease: results from the National Institutes of Health–National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circulation 2006; 114: 894-904.

7. Mygind ND, Michelsen MM, Pena A, et al. Coronary microvascular function and cardiovascular risk factors in women with angina pectoris and no obstructive coronary artery disease: the iPOWER study. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: e003064.

8. Recio-Mayoral A, Mason JC, Kaski JC, Rubens MB, Harari OA and Camici PG. Chronic inflammation and coronary microvascular dysfunction in patients without risk factors for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 1837-1843.

9. Ishimori ML, Martin R, Berman DS, et al. Myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011; 4: 27-33.

10. Sara JD, Ahmad A, Toya T, Suarez Pardo L, Lerman LO and Lerman A. Anxiety disorders are associated with coronary endothelial dysfunction in women with, chest pain and nonobstructive coronary artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc 2021; 10: e021722.

11. Taqueti VR, Di Carli MF. Coronary microvascular disease pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic options. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 72: 2625-2641.

12. Ong P, Camici PG, Beltrame JF, et al. International standardization of diagnostic criteria for microvascular angina. Int J Cardiol 2018; 250: 16-20.

13. Beltrame JF, Tavella R, Jones D, Zeitz C. Management of ischaemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA). BMJ 2021; 375: e060602.

14. Mortensen MB, Dzaye O, Steffensen FH, et al. Impact of plaque burden versus stenosis on ischemic events in patients with coronary atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76: 2803-2813.

15. Ford TJ, Stanley B, Good R, et al. Stratified medical therapy using invasive coronary function testing in angina: the CorMicA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 72: 2841-2855.