Migraine in 2025: an update on management

Migraine is a common and disabling neurological condition that affects quality of life. The three key treatment strategies for migraine are a personalised management approach addressing lifestyle factors, acute medications and preventive medications. With modern treatments, most patients can expect substantial improvement in symptoms and quality of life.

- Migraine has a significant impact on quality of life and is the second leading cause of disability worldwide.

- The four clinical phases of a migraine attack include prodrome, migraine aura, headache and postdrome.

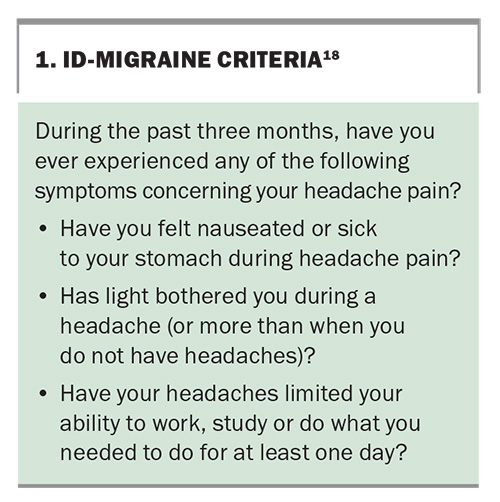

- The ID-Migraine questionnaire can be used to identify patients with migraine in primary care, and screening for red flags for secondary headaches should be carried out using the SNNOOP10 list.

- Migraine can be managed using lifestyle management (reviewing sleep, exercise, diet and stress and keeping a headache diary), acute treatment and preventive treatment.

- Acute treatments include simple analgesics, NSAIDS, triptans and antiemetics. Newly available gepants (oral calcitonin gene-related peptide [CGRP] antagonists) have a role when triptans are not tolerated or are contraindicated.

- Preventive treatments involve selected oral medications and supplements, and advanced treatment options include onabotulinumtoxinA and CGRP monoclonal antibodies.

According to the Global Burden of Disease studies, migraine represents the second leading cause of disability worldwide and the leading cause of reversible disability in people under the age of 50 years.1,2 In Australia, migraine affects about one in five people and is among the 20 most common conditions managed by GPs, being responsible for one in 100 GP encounters.3 Unsurprisingly therefore, it is estimated to cost the economy AU$35.7 billion in direct health and indirect costs.4

Each year 2.5% of patients with migraine progress from episodic (less than 15 headache days per month) to chronic migraine (15 or more headache days per month), with associated negative impacts on quality of life and health resources.5 The key modifiable risk factors contributing to the progression of disability are obesity, snoring, stressful events, depression or anxiety and significantly ineffective preventive treatment. These risk factors increase severity or frequency of migraine, leading to increased attack frequency and acute analgesic overuse.5 This article updates our previous 2022 article6 and outlines the diagnosis and management of migraine, highlighting the importance of careful assessment for differential diagnoses and an approach to management that includes lifestyle interventions and pharmacological treatment.

Pathophysiology

The 20th century vascular theory of migraine is now recognised to be incomplete, and while the pathophysiology of migraine is complex and reviewed elsewhere, several key points bear highlighting.7,8 Although the trigger is still debated, imaging studies show that several brain regions, including the hypothalamus, are activated 24 to 72 hours before a migraine attack.9 These studies provide a pathophysiological correlation for the four clinical phases of a migraine attack, which are prodrome, migraine aura, headache and postdrome (Figure 1).7,10

A migraine aura is believed to be caused by a spreading ‘wave’ of depolarisation and subsequent refractory period across a cortical region.11 The pain of a migraine attack itself is caused by activation of the trigeminocervical complex in the brainstem, along with other pain circuits, and subsequent release of a variety of neuropeptides including calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP).7,8 CGRP, which has emerged as a therapeutic target, acts on the trigeminovascular system, a complex system rich in CGRP and 5HT receptors that, as a potent vasodilator, causes the vascular changes originally observed in migraine.12

Presentation and assessment

Migraine is defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition (ICHD-3) and further classified by frequency as either episodic or chronic and by the presence or absence of aura (Table 1).13 The four phases of a migraine are described above. The headache phase is easily identified by the presence of pain; however, careful questioning can often identify features of a prodromal phase, such as yawning and increased urine production. Some prodromal symptoms such as neck stiffness and food cravings can be difficult to interpret because they might be regarded by the patient as migraine triggers.

Migraine aura is reported in 30% of patients and does not necessarily precede each headache. More than 95% of patients with aura experience a visual phenomenon, often a scintillating scotoma that may start centrally, often with jagged edges (fortification spectra) (Figures 2a and b).14,15 Other manifestations may be sensory, motor, speech or, rarely, brainstem symptoms. Aura causes fully reversible, typically unilateral symptoms. Certain features help to distinguish it from important differential diagnoses. Migraine aura develops gradually, evolving over 10 to 30 minutes, lasting 5 to 60 minutes and often consisting of positive symptoms (paraesthesia) followed by negative symptoms (numbness). Transient ischaemic attack, by contrast, begins suddenly, persists for minutes to hours, generally as negative symptoms, and only affects cranial vascular territories. Focal seizures also progress gradually (such as with a Jacksonian march), but are of shorter duration, lasting less than two minutes.16

The pain phase of a migraine attack is often unilateral at onset; however, there is often bilateral pain, so unlike some other conditions such as cluster headache, migraine is generally not ‘side-locked’.17 Pain may be throbbing in character and typically lasts from four to 72 hours.13 Features that differentiate migraine pain from other headaches include worsening with physical activity and the migrainous phenomena of nausea, or photophobia and phonophobia, so the symptoms cause many patients to avoid activity and lie down in a dark room.13 Finally, a postdrome may be identified and include symptoms of fatigue, depression, irritability and reduced concentration (Figure 1).

Diagnosis

Migraine is a clinical diagnosis and further investigation should only be considered in the appropriate clinical context.18 The ID-Migraine questionnaire is a useful screening tool to help identify patients with migraine in primary care (Box 1)18 and should be performed alongside screening for red flags for secondary headaches using the SNNOOP10 red flags for secondary headaches criteria (Table 2).19,20

Hypothyroidism and vitamin D and iron deficiency may be associated with increased headache frequency and should be identified and treated.21-23 Because incidental findings, found in 2% of the general population, may increase distress and provoke further unproductive investigation, routine neuroimaging is not recommended for patients with a normal neurological examination and no atypical headache features or red flags.24,25 Specific consideration should be given to important mimics that may be differentiated on history and include the following.26

- Cluster headache – presents with excruciating, strictly side-locked pain over the temple and orbital region, with accompanying agitation and cranial autonomic features (e.g. tearing, nasal congestion).27 Differentiated from migraine by its side-locked pain and agitation, cluster headaches are typically shorter (averaging 90 minutes) and typically exhibit circadian (classically one to two hours after sleep onset) and circannual periodicity (bouts occur at the same time of year, typically in autumn and spring).

- Hemicrania continua – presents with strictly side-locked pain that is continuous from onset.13 Differentiated from migraine by its side-locked and continuous nature, it may also present with agitation and autonomic symptoms.

- New daily persistent headache – differentiated from migraine by its unremitting (persistent) nature and clearly remembered day of onset.

- Tension-type headache – described as a featureless headache, it is distinguished from migraine by shorter and less disabling attacks with an absence of migrainous features (i.e. throbbing pain, nausea, photophobia or phonophobia).13

- Sinus headache – although often diagnosed from imaging findings or frontal tenderness, headache caused by chronic sinusitis is relatively rare. In one formative study, 81% of patients with the label actually had migraine and management was delayed by an average of 7.8 years.28

Approach to management

The management of migraine can be broken into three pillars: lifestyle management, acute treatment and preventive treatment. All patients benefit from lifestyle management and optimisation of acute treatment, whereas patients with four or more migraine days a month or attacks that are difficult to control may benefit from preventive treatment.

Lifestyle management

Lifestyle management is likely an effective treatment that affords patients autonomy over their health. Studies on lifestyle interventions in managing migraine are limited; however, some suggest engaging in regular positive lifestyle behaviours may help limit episodes of chronic migraine, with a number needed to treat of just two in a population of people with chronic migraine.29 The mnemonic SEEDS (sleep, exercise, eating, diary, stress) is a useful framework for framing a discussion around lifestyle management.30

Sleep

Although snoring is a risk factor for progression to chronic migraine, obstructive sleep apnoea does not occur more frequently in patients with migraine.31,32 The presence of sleep-disordered breathing, early morning headaches or daytime somnolence should, however, prompt further investigation for obstructive sleep apnoea as a modifiable factor in people with migraine. A bidirectional relationship may exist between migraine and insomnia, with a further association with frequency and severity of migraine attacks.33

Strategies to improve sleep quality include sleep restriction, improved sleep hygiene and stimulus control. Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia has also been shown to improve headache frequency.34 The Sleep Health Foundation has detailed resources that are of benefit (https://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au).

Exercise

A recent meta-analysis of 265 studies found that aerobic exercise of 30 to 50 minutes, three to five times a week over six weeks has a modest effect on the frequency of migraine attacks.35 Exercise was also shown to be noninferior to pharmacotherapy and patients saw an additive benefit of therapies.30 A graded exercise program is important for improving tolerability in patients with migraine.

Eating (diet)

Dietary triggers of migraine are reported by up to one-third of patients, with 44%, 27% and 7.5% reporting migraines triggered by fasting, alcohol consumption and chocolate consumption, respectively.36,37 However, the role of specific dietary triggers should be interpreted carefully as the hypothalamic activation and food craving that often precede an attack can be mistaken for triggers.7,9,36 For example, one double-blinded study showed that chocolate did not trigger migraines.38

Dietary advice should be practical and focus on avoiding general triggers, such as fasting, and making dietary choices to maintain stable blood glucose levels.39,40 Although the role of caffeine in migraine is not fully understood, abrupt withdrawal from caffeine can potentiate headaches, with a dose-dependent relationship between cessation and withdrawal symptoms.41 A gradual reduction to the minimum tolerable level or a maximum of 200 mg of caffeine per day (two cups of coffee) is a reasonable approach.42 Several dietary interventions show improvement in headache frequency, including low-fat, low glycaemic and Mediterranean diets, and may be recommended to patients.3 Dietary triggers for migraine vary greatly between patients, so a generic list of foods to be avoided is not especially helpful.

Diary

Keeping a headache diary is recommended to help monitor disease activity, effectiveness of preventive treatment and frequency of analgesic use. Headache diary templates are available on the Australian and New Zealand Headache Society website (https://anzheadachesociety.org/for-patients). Electronic versions are available for smart devices.

Stress

The causal relationship between stress and migraine remains unclear; however, periods of stress are associated with both new-onset migraine and transformation to chronic migraine, and change in levels of stress (both increased and decreased) are a risk factor for a migraine attack.43 Accordingly, stress-centred interventions for managing migraine, such as relaxation therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy and biofeedback, are supported by grade A evidence.44

Acute treatments

The goal of the acute treatment of migraine is pain freedom within two hours. This may be achieved through monotherapy with a simple analgesia or, if analgesia alone is ineffective, by the addition of a triptan or an antiemetic (Box 2).45 Some key principles to enhance efficacy include:

- analgesics are more effective when taken early during an attack46

- a combination of analgesics is more effective than monotherapy46

- beyond the antiemetic effect, metoclopramide provides additional analgesic effect and improves the response to other analgesics.47,48

Nonpharmacological interventions, such as meditation and ice-packs, have also shown effect.49,50

Triptans

In patients without a significant vascular history, triptans are an effective treatment. Studies have shown they achieved pain freedom as monotherapy in 18 to 50% of cases.51 Initial triptan selection is often based on route of administration – rizatriptan and sumatriptan are available as nonoral preparations for patients with prominent early nausea. In patients who do not have initial pain relief with other triptans, switching to eletriptan 80 mg or rizatriptan 10 mg may be more effective.52 In patients in whom analgesia has a waning effect, longer-acting analgesics such as naratriptan or naproxen may be preferable.

Gepants and ditans

Two new classes of drugs for acute treatment have become available in recent years: gepants and ditans. The gepants are oral CGRP antagonists. At present, only rimegepant is available in Australia, but other drugs may become available in the future. Currently, rimegepant is not PBS funded, making it more expensive than triptans. It may be valuable where the use of triptans is limited by side effects or concern about potential cardiovascular complications, or where the frequency of triptan use raises concerns about medication overuse headache (MOH).53-55 Gepants are thought to carry a much lower risk of causing MOH than triptans.55

Ditans are 5HT1F receptor agonists that appear to have less potential for vascular side effects than triptans.54 The first of this class (lasmiditan) is available overseas, but not yet in Australia.

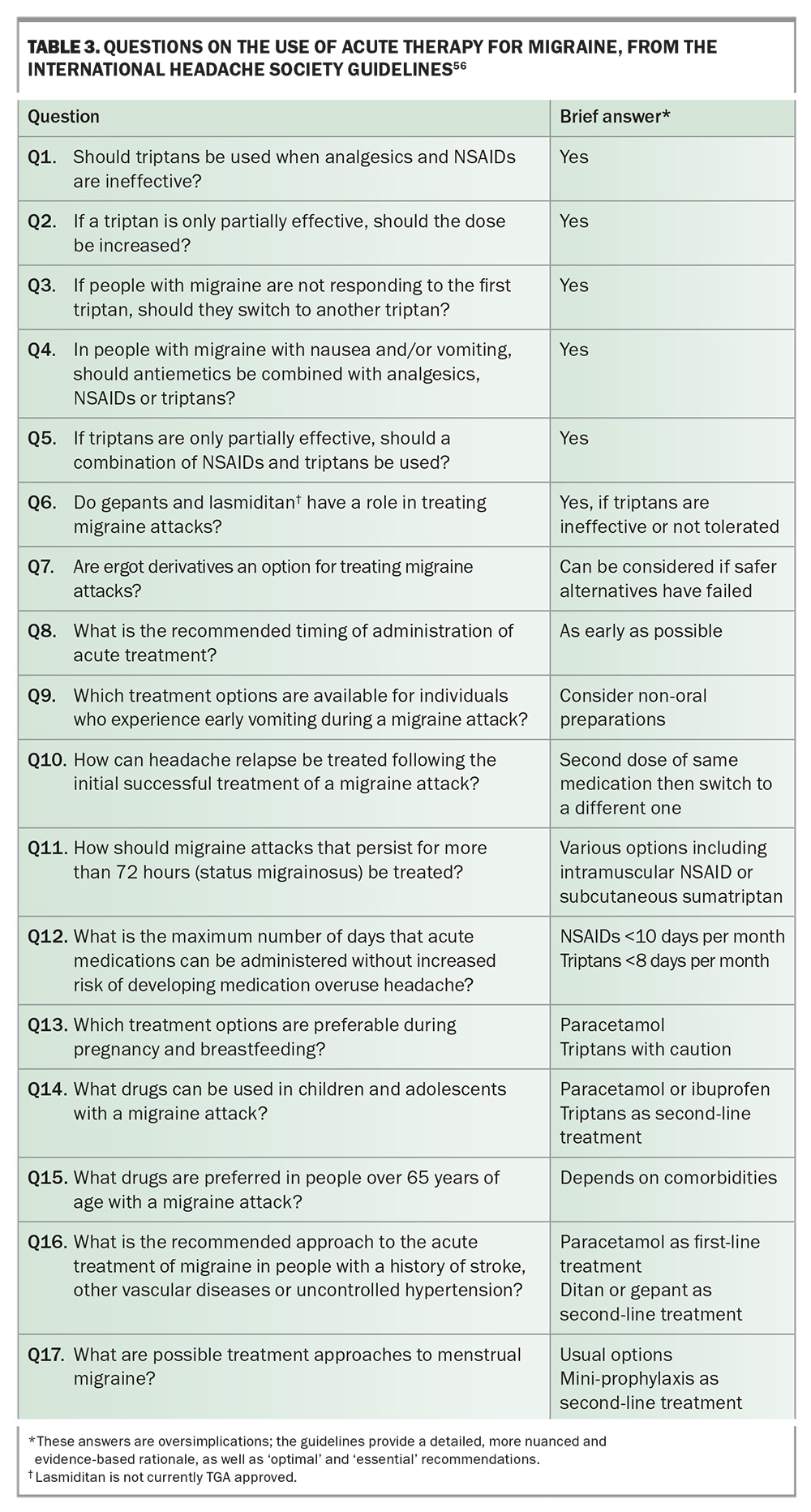

A recent guideline from the International Headache Society provides practical advice on acute therapy in various situations.56 It emphasises the value of triptans and notes that some treatment options are not universally available. The guidelines are summarised in Table 3.56

A systematic review and network meta-analysis of medication for acute migraine treatment confirmed the clinical impression that, in general, triptans are more effective than gepants or ditans.57 The authors concluded that overall, eletriptan, rizatriptan, sumatriptan and zolmitriptan were more efficacious than rimegepant, lasmiditan and ubrogepant (the latter two are not yet available for use in Australia). The newer agents have a place when side effects or concerns about cardiovascular risk or medication overuse limit the use of triptans.

Overuse of acute medications

Overuse of acute analgesia for any reason predisposes patients with migraine to developing a secondary headache, MOH.13 MOH occurs as a result of further sensitisation of the pain circuits of the brain and diminished ability to inhibit painful signals, resulting in headaches that are more frequent and refractory to both acute and preventive treatments.58 Unfortunately, up to 70% of patients with chronic daily headaches suffer comorbid MOH.59

Prevention is the best treatment for MOH, and patients must be counselled to not exceed 10 days of triptan use per month, or 15 days total for simple analgesics.13 Opiates are not recommended for migraine by the authors because of potential issues of both MOH and dependence. Few studies exist for MOH management; however, in conjunction with preventive treatments, bridging strategies, including use of slow-release naproxen (for triptan overuse) or prednisolone and withdrawal (although evidence for this is limited and mixed), are recommended (Box 2).26,45,55,60

Preventive treatments

Preventive treatment for migraine is indicated to limit the impact of migraine and risk of acute analgesic overuse for patients who have more than four days of migraine per month or those with disabling disease.61

Oral medications

Selected oral medications are outlined in Table 4.62,63 Although evidence based, several preventive treatments for migraine are available for off-label use on the PBS. Guiding principles for the use of oral preventive treatments for migraine include:

- given no preventive oral medication is clearly superior, the choice of medication is best guided by side effect profile, comorbidity and patient preference

- in the absence of side effects, medications should be continued for a minimum of eight to 12 weeks at a moderate dose to assess efficacy

- in the absence of side effects, the dose should be titrated to assess efficacy and optimise response.

Supplements

Some patients may prefer supplements for migraine prevention; however, evidence for their efficacy is limited and mixed. Some studies suggest magnesium, riboflavin, coenzyme Q10 and cholecalciferol are effective and safe for migraine prevention.22,64 Vitamin D deficiency has been shown and mitochondrial energy depletion suggested in people with migraines.22,65 Evidence suggests the following supplemental treatment may be considered for suitable patients:

- 400 to 600 mg of magnesium (elemental) daily66

- 200 mg of riboflavin daily60

- 150 to 300 mg of coenzyme Q10 daily60

- replacement of vitamin D to normal levels.67

OnabotulinumtoxinA and CGRP monoclonal antibodies

Advanced treatment options are available for patients with chronic migraine in whom three preventive medications have not been effective or are contraindicated and any comorbid MOH has been addressed. These advanced treatments include onabotulinumtoxinA (OnaB-A) and the CGRP monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) fremanezumab and galcanezumab (given as monthly subcutaneous injections to the stomach or thighs) and eptinizumab (given by intravenous infusion every three months).

OnaB-A must be started by a neurologist, and CGRP mAbs may be prescribed by GPs as either initiating or continuing treatment in shared care with a neurologist. OnaB-A is given as a series of 31 subcutaneous injections through the head and neck at 12-weekly intervals and may be particularly useful for patients with neck-muscle activation, bruxism or multiple comorbidities because of its limited systemic uptake.

The PBS requirements to prescribe these injectables include formal headache diaries that record headache and migraine frequency. Unnecessary delays in treatment can be avoided if these are available when the patient sees a neurologist. The updated PBS criteria may result in the GP specialist leading the assessment of response to initial therapy. In this case, there is some important nuance in the PBS criteria.

To continue treatment, the PBS criteria for OnaB-A require patients to achieve at least a 50% reduction in headache days per month (i.e. any form of headache) compared with baseline (assessed at six months), whereas CGRP mAbs require at least a 50% reduction in migraine days compared with baseline (assessed at three months). These migraine days are often identifiable by the presence of photophobia, nausea or activity restriction. Specific evaluation for these outcomes is not only clinically valuable in helping decide whether to persist with or change treatment but is administratively vital to document the PBS criteria that allow a therapy to be continued. PBS criteria are summarised in Table 5.68

Although there are no high-quality data assessing the relative efficacy of OnaB-A and CGRP mAbs, both have shown efficacy in treating headaches in clinical trials. OnaB-A achieved a 50% or greater improvement in headaches in 47.1% of patients.69 CGRP mAbs showed a 50% or greater reduction in headaches in 30 to 40% of patients.70

The oral CGRP antagonist rimegepant can also be used for prophylaxis in episodic migraine (migraine days on <15 days per month), given at a dose of 75 mg every second day.71 As rimegepant is not yet PBS funded, it is more expensive than other options. It can have a practical use, however, to provide short-term cover at times of high risk for migraine breakthrough. For example, patients who have migraines reappearing towards the end of the 12 weeks between OnaB-A injections may find this strategy helpful. Some patients may use a short course for menstrual migraine mini-prophylaxis or to protect against migraines at crucial times such as weddings or exams.

Common, theoretical and potential side effects of CGRP antagonists

Overall, gepants and CGRP mAbs have been well tolerated, with a few shared side effects. Local injection site reactions occur in about 5% of patients who use CGRP mAbs. The most common side effect appears to be constipation (although perhaps more commonly with the CGRP mAb erenumab, which is currently not available in Australia). Real-world data suggest constipation may occur in 10 to 20% of patients who use CGRP mAbs, as opposed to the 1.4 to 2.1% reported in trials.72

As CGRP is widely expressed throughout the body, theoretically off-target effects of blockade may be possible. There is little evidence yet of problems from coronary or cerebral vasoconstriction, but slight worsening of hypertension has been noted.73,74 There have been anecdotal reports of occasional aggravation of inflammatory disorders such as psoriasis from CGRP mAbs.75

As for most new medications, there is no experience in the paediatric or geriatric population and no human data on use during pregnancy or lactation. CGRP has a role in placental development, so use by pregnant or breastfeeding women is not recommended. Because of the long half-life of CGRP mAbs, they should be ceased at least five months before pregnancy.76

Conclusion

Migraine is a common presentation in clinical practice that requires a comprehensive approach to management. Important differential diagnoses should be assessed in the context of the four clinical phases of migraine. Addressing lifestyle factors that may contribute to migraine can help reduce migraine frequency and morbidity. Pharmacological treatments include acute and preventive medications and should be used appropriately to optimise response and reduce acute analgesic overuse. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Hilliard: None.

Dr Ray reports in the past 36 months he has received honoraria for educational presentations for AbbVie, Novartis and Viatris. He has served on medical advisory boards for Pfizer, Viatris and Eli Lilly. His institution has received funding for research grants, clinical trials and projects supported by the International Headache Society, Brain Foundation, Lundbeck, AbbVie, Pfizer and Aeon.

Dr Hutton has served on advisory boards for Sanofi-Genzyme, Novartis, Teva, Eli Lilly, Allergan and Lundbeck; been involved in clinical trials sponsored by Novartis, Teva, Xalud and Cerecin; and received payment for educational presentations from Allergan, Teva, Eli Lilly and Novartis.

Professor Stark has served on advisory boards for Teva, Eli Lilly, AbbVie, Viatris and Lundbeck; and received payment for educational presentations from AbbVie, Teva, Eli Lilly and Viatris.

References

1. James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018; 392: 1789-858.

2. Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Vos T, Jensen R, Katsarava Z. Migraine is first cause of disability in under 50s: will health politicians now take notice? J Headache Pain 2018; 19: 17-20.

3. Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2015–16. General practice series no. 40. Sydney: Sydney University Press; 2015. Available online at: https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/15514 (accessed May 2025).

4. Deloitte Access Economics. Migraine in Australia whitepaper. Measuring the impact. Canberra: Deloitte; 2018. Available online at: https://www.deloitte.com/au/en/services/economics/perspectives/migraine-australia-whitepaper.html (accessed May 2025).

5. Manack AN, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine: epidemiology and disease burden. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2011; 15: 70-78.

6. Hilliard T, Ray JC, Hutton EJ, Stark RJ. Migraine in 2022: an update on management. Medicine Today 2022; 23: 57-64.

7. Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, Hoffmann J, Schankin C, Akerman S. Pathophysiology of migraine: a disorder of sensory processing. Physiol Rev 2017; 97: 553-622.

8. Ashina M. Migraine. New Engl J Med 2020; 383: 1866-1876.

9. Karsan N, Goadsby PJ. Imaging the premonitory phase of migraine. Front Neurol 2020; 11: 140.

10. Rasmussen BK, Olesen J. Migraine with aura and migraine without aura: an epidemiological study. Cephalalgia 1992; 12: 221-228.

11. Charles AC, Baca SM. Cortical spreading depression and migraine. Nat Rev Neurol 2013; 9: 637-644.

12. Marichal-Cancino BA, González-Hernández A, Guerrero-Alba R, Medina-Santillán R, Villalón CM. A critical review of the neurovascular nature of migraine and the main mechanisms of action of prophylactic antimigraine medications. Expert Rev Neurother 2021; 21: 1035-1050.

13. International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders 3rd edition. London: International Headache Society; 2021. Available online at: https://ichd-3.org/ (accessed May 2025).

14. Viana M, Tronvik EA, Do TP, Zecca C, Hougaard A. Clinical features of visual migraine aura: a systematic review. J Headache Pain 2019; 20: 64.

15. Kim KM, Kim BK, Lee W, Hwang H, Heo K, Chu MK. Prevalence and impact of visual aura in migraine and probable migraine: a population study. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 426.

16. Jenssen S, Gracely EJ, Sperling MR. How long do most seizures last? A systematic comparison of seizures recorded in the epilepsy monitoring unit. Epilepsia 2006; 47: 1499-1503.

17. Leone M, Frediani F, Torri W, et al. Clinical considerations on side-locked unilaterality in long-lasting primary headaches. Headache 1993; 33: 381-384.

18. Ray JC, Hutton EJ. Diagnostic tests: imaging in headache disorders. Aust Prescrib 2022; 45: 88-92.

19. Cousins G, Hijazze S, Van de Laar FA, Fahey T. Diagnostic accuracy of the ID migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Headache 2011; 51: 1140-1148.

20. Do TP, Remmers A, Schytz HW, et al. Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice. Neurology 2019; 92: 134-144.

21. Spanou I, Bougea A, Liakakis G, et al. Relationship of migraine and tension‐type headache with hypothyroidism: a literature review. Headache 2019; 59: 1174-1186.

22. Ghorbani Z, Togha M, Rafiee P, et al. Vitamin D in migraine headache: a comprehensive review on literature. Neurol Sci 2019; 40: 2459-2477.

23. Tayyebi A, Poursadeghfard M, Nazeri M, Pousadeghfard T. Is there any correlation between migraine attacks and iron deficiency anemia? A case-control study. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res 2019; 13: 164-171.

24. Evans RW, Burch RC, Frishberg BM, et al. Neuroimaging for migraine: the American Headache Society systematic review and evidence‐based guideline. Headache 2020; 60: 318-336.

25. Morris Z, Whiteley WN, Longstreth WT, et al. Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2009; 339: b3016-b3016.

26. Ray JC, Macindoe C, Ginevra M, Hutton EJ. The state of migraine: an update on current and emerging treatments. Aust J Gen Pract 2021; 50: 915-921.

27. Ray JC, Stark RJ, Hutton EJ. Cluster headache in adults. Aust Prescr 2022; 45: 15-20.

28. Al-Hashel JY, Ahmed SF, Alroughani R, Goadsby PJ. Migraine misdiagnosis as a sinusitis, a delay that can last for many years. J Headache Pain 2013; 14: 97.

29. Agbetou M, Adoukonou T. Lifestyle modifications for migraine management. Front Neurol 2022; 13: 719467.

30. Robblee J, Starling AJ. SEEDS for success: lifestyle management in migraine. Cleve Clin J Med 2019; 86: 741-749.

31. May A, Schulte LH. Chronic migraine: risk factors, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol; 2016; 12: 455-464.

32. Kristiansen HA, Kværner KJ, Akre H, Øverland B, Russell MB. Migraine and sleep apnea in the general population. J Headache Pain 2011; 12: 55-61.

33. Tiseo C, Vacca A, Felbush A, et al. Migraine and sleep disorders: a systematic review. J Headache Pain 2020; 21: 126.

34. Smitherman TA, Kuka AJ, Calhoun AH, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia to reduce chronic migraine: a sequential bayesian analysis. Headache 2018; 58: 1052-1059.

35. Lemmens J, De Pauw J, Van Soom T, et al. The effect of aerobic exercise on the number of migraine days, duration and pain intensity in migraine: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Headache Pain 2019; 20: 16.

36. Hindiyeh NA, Zhang N, Farrar M, Banerjee P, Lombard L, Aurora SK. The role of diet and nutrition in migraine triggers and treatment: a systematic literature review. Headache 2020; 60: 1300-1316.

37. Tai MLS, Yap JF, Goh CB. Dietary trigger factors of migraine and tension-type headache in a South East Asian country. J Pain Res 2018; 11: 1255-1261.

38. Marcus D, Scharff L, Turk D, Gourley L. A double-blind provocative study of chocolate as a trigger of headache. Cephalalgia 1997; 17: 855-862.

39. Abu-Salameh I, Plakht Y, Ifergane G. Migraine exacerbation during Ramadan fasting. J Headache Pain 2010; 11: 513-517.

40. Nas A, Mirza N, Kahlho J, et al. Impact of breakfast skipping compared with dinner skipping on regulation of energy balance and metabolic risk. Am J Clin Nutr 2017; 105: 1351-1361.

41. Nowaczewska M, Wicí Nski M, Ka´zmierczak W. The ambiguous role of caffeine in migraine headache: from trigger to treatment. Nutrients 2020; 33: 381-384.

42. Silverman K, Evans SM, Strain EC, Griffiths RR. Withdrawal syndrome after the double-blind cessation of caffeine consumption. N Engl J Med 1992; 327: 1109-1114.

43. Stubberud A, Buse DC, Kristoffersen ES, Linde M, Tronvik E. Is there a causal relationship between stress and migraine? Current evidence and implications for management. J Headache Pain 2021; 22: 155.

44. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 2019; 51: 1-18.

45. Mounds R, Aplin P, Boundy K, et al. Acute treatment for migraine with a triptan. In: Therapeutic Guidelines. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2017.

46. Law S, Derry S, Moore RA. Sumatriptan plus naproxen for the treatment of acute migraine attacks in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 4(4): CD008541.

47. Schulman EA, Dermott KF. Sumatriptan plus metoclopramide in triptan-nonresponsive migraineurs. Headache 2003; 43: 729-733.

48. Friedman BW, Irizarry E, Williams A, et al. A randomized, double‐dummy, emergency department‐based study of greater occipital nerve block with bupivacaine vs intravenous metoclopramide for treatment of migraine. Headache 2020; 60: 2380-2388.

49. Fichtel A, Larsson B. Does relaxation treatment have differential effects on migraine and tension-type headache in adolescents? Headache 2001; 41: 290-296.

50. Ucler S, Coskun O, Inan LE, Kanatli Y. Cold therapy in migraine patients: open-label, non-controlled, pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2006; 3: 489-493.

51. Cameron C, Kelly S, Hsieh SC, et al. Triptans in the acute treatment of migraine: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Headache 2015; 55: 221-235.

52. Xu H, Han W, Wang J, Li M. Network meta-analysis of migraine disorder treatment by NSAIDs and triptans. J Headache Pain 2016; 17: 113.

53. Lipton RB, Blumenfeld A, Jensen CM, et al. Efficacy of rimegepant for the acute treatment of migraine based on triptan treatment experience: pooled results from three phase 3 randomized clinical trials. Cephalalgia 2023; 43.

54. Mathew S, Ailani J. Traditional and novel migraine therapy in the aging population. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2019; 23: 42.

55. Croop R, Berman G, Kudrow D, et al. A multicenter, open-label long-term safety study of rimegepant for the acute treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia 2024; 44.

56. Puledda F, Sacco S, Diener H-C, et al. International Headache Society global practice recommendations for the acute pharmacological treatment of migraine. Cephalalgia 2024; 44.

57. Karlsson WK, Ostinelli EG, Zhuang ZA, et al. Comparative effects of drug interventions for the acute management of migraine episodes in adults: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ 2024; 386: e080107.

58. Meng ID, Dodick D, Ossipov MH, Porreca F. Pathophysiology of medication overuse headache: insights and hypotheses from preclinical studies. Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 851-860.

59. Westergaard ML, Hansen EH, Glümer C, Olesen J, Jensen RH. Definitons of medication overuse headache in population-based studies and their implications on prevalence estimates: a systematic review. Cephalalgia 2014; 34(6): 409-425.

60. Diener H, Dodick D, Evers S, et al. Pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment of medication overuse headache. Lancet Neurol 2019; 18: 891-902.

61. Ailani J, Burch RC, Robbins MS. The American Headache Society consensus statement: update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 2021; 61: 1021-1039.

62. Evers S, Áfra J, Frese A, et al. EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine - revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2009; 16: 968-981.

63. Loder E, Burch R, Rizzoli P. The 2012 AHS/AAN guidelines for prevention of episodic migraine: a summary and comparison with other recent clinical practice guidelines. Headache 2012; 52: 930-945.

64. Tepper S. Nutraceutical and other modalities for the treatment of headache. Continuum 2015; 21: 1018-1031.

65. Welch K Ramadan, N. Mitochondria, magnesium and migraine. J Neurol Sci 1995; 134: 9-14.

66. Rajapakse T, Pringsheim T. Nutraceuticals in migraine: a summary of existing guidelines for use. Headache 2016; 56: 808-816.

67. Rapisarda L, Mazza MR, Tosto F, Gambardella A, Bono F, Sarica A. Relationship between severity of migraine and vitamin D deficiency: a case-control study. Neurol Sci 2018; 39(Suppl 1): 167-168.

68. Australian Government. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Canberra: Australian Government; 2025. Available online at: https://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/home (accessed May 2025).

69. Ray JC, Hutton EJ, Matharu M. OnabotulinumtoxinA in migraine: a review of the literature and factors associated with efficacy. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 2898.

70. Ray JC, Kapoor M, Stark RJ, et al. Calcitonin gene related peptide in migraine: current therapeutics, future implications and potential off-target effects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2021; 92: 1325-1334.

71. Croop R, Lipton RB, Kudrow D, et al. Oral rimegepant for preventive treatment of migraine: a phase 2/3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2021; 397: 51-60.

72. Ray JC, Kapoor M, Stark RJ, et al. Calcitonin gene related peptide in migraine: current therapeutics, future implications and potential off-target effects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2021; 92: 1325-1334.

73. Chaitman BR, Ho AP, Behm MO, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of the effects of telcagepant on exercise time in patients with stable angina. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2012; 91: 459-466.

74. Sacco S, Bendtsen L, Ashina M, et al. European headache federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene related peptide or its receptor for migraine prevention. J Headache Pain 2019; 20: 6.

75. Ray JC, Allen P, Bacsi A, et al. Inflammatory complications of CGRP monoclonal antibodies: a case series. J Headache Pain 2021; 22: 121.

76. Al-Hassany L, Goadsby PJ, Danser AHJ, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Calcitonin gene-related peptide-targeting drugs for migraine: how pharmacology might inform treatment decisions. Lancet Neurol 2022; 21: 284-294.