Systemic vasculitides. Part 1: Large, medium and variable vessel diseases

Vasculitis, or inflammation of vessel walls, is common and consists of a diverse array of disease entities encompassing virtually all organ systems. As onset is typically subacute and nonspecific, affected patients usually first seek attention from primary care providers. Size and distribution of the affected vasculature dictate end-organ manifestations and preliminary screening tests. Complications may carry high morbidity and mortality; therefore, prompt recognition, specialist referral and institution of immunosuppressive therapy are crucial to obviate potentially poor outcomes.

- Systemic vasculitides are a group of important diseases caused by vessel wall inflammation and its end-organ effects. They are classified by the size of the vessels affected.

- Although many cases are idiopathic, important secondary causes of vasculitis include connective tissue diseases, haematological malignancies and chronic infections. These conditions must be considered when investigating patients with vasculitis.

- Lethal and highly morbid complications of vasculitis including visual compromise, renal dysfunction, haemoptysis, vascular aneurysms and occlusive vascular disease must be considered when diagnosing vasculitis. Early specialist involvement is crucial if these complications are present.

- Management involves the use of corticosteroids and immunosuppressant medications, thus chronic complications such as osteoporosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and risk of opportunistic infections and secondary malignancies must be addressed in the long-term management of patients with vasculitis.

The vasculitides are a diverse group of diseases characterised by inflammation of the vascular walls and classified by the size of affected vessels. The most widely accepted classification criteria are the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature.1 Conditions are grouped into large, medium and small vessel disease. Systemic vasculitis is clinically nonspecific and may be suggested by the presence of constitutional symptoms including fevers, sweats, fatigue, arthralgias, myalgias and weight loss in combination with evidence of end-organ dysfunction. Although vasculitis may be idiopathic and primary, important secondary causes include:

- systemic inflammatory diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and relapsing polychondritis

- haematological malignancies such as lymphoma and multiple myeloma

- chronic infections such as hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV), HIV, syphilis and infective endocarditis (IE).

Simple infections of skin and respiratory systems and, in at-risk populations, tuberculosis should be considered and excluded by means of microbiological culture, serology and relevant radiology. Recognition of critical complications of vasculitis including acute renal failure, haemoptysis, coronary artery aneurysm, acute limb ischaemia and blindness is prudent, and hospitalisation and prompt specialist involvement is crucial. The management of most vasculitides centres on corticosteroids and immunosuppression, thus chronic complications of therapies such as diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, malignancy risk and opportunistic infections are additional important considerations for long-term management. In this first of a two-part series, we discuss key clinical features, relevant investigations and an approach to management of large and medium vessel diseases (Table). Part 2 of this series will focus on small vessel diseases.

Classification and clinical features

Large vessel vasculitis

Giant cell arteritis

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) (Figure 1) is the most common systemic vasculitis and occurs primarily in elderly adults.2 Hallmark clinical manifestations of GCA are constitutional symptoms including fever, bitemporal headache, jaw claudication (the most specific symptom)3 and amaurosis fugax (transient visual loss) (Box 1). There is a strong association with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR): roughly half of patients with GCA have PMR and about 15% of patients with PMR have GCA.4

Complications of GCA can be serious and include irreversible blindness, aortic dissection and acute aortic regurgitation. Basic blood tests typically reveal an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and, more specifically, the presence of C-reactive peptides, indicating inflammation.

Temporal artery biopsy, generally obtained from the symptomatic side, remains the gold standard for diagnosing GCA. High-dose corticosteroids are the first-line treatment and are usually effective in inducing remission. Corticosteroids reduce the risk of visual complications and should be started promptly while sight is intact. If started before the development of visual symptoms, the risk of blindness is less than 1%.2 The timing of a temporal artery biopsy should not affect urgent administration of corticosteroids to symptomatic patients. After two to four weeks of high-dose therapy, corticosteroids are weaned slowly over at least six months. Relapses most commonly occur in patients taking corticosteroid doses of less than 20 mg daily and are managed with increased doses and clinical and biochemical monitoring. In patients with corticosteroid toxicity or comorbid disease, there are several options for maintenance therapy including methotrexate, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide. Tocilizumab, a humanised monoclonal antibody directed against interleukin-6, has demonstrated efficacy as an adjuvant therapy in maintaining clinical remission in patients with GCA, and is now included in most guidelines.5,6 In all cases of GCA, it is important to manage long-term sequelae of corticosteroid use including opportunistic infections, osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and obesity.

Takayasu arteritis

Takayasu arteritis (TAK), or pulseless disease, primarily affects the aorta and its proximal branches, especially the subclavian arteries. Women are more commonly affected and nearly all cases occur in patients under the age of 40 years. Onset is usually subacute and symptoms nonspecific, often resulting in a long delay to diagnosis. Patients with TAK may experience limb claudication and neurological symptoms associated with ischaemia. Pulses in affected limbs are classically diminished or absent and arterial bruits may be detected over affected sites. Affected limbs may yield spuriously low blood pressures. The subclavian steal phenomenon may occur, wherein severe stenosis or obstruction of the proximal subclavian artery causes transient episodes of vertebrobasilar ischaemia. Reversal of blood flow in the vertebral artery on the same side of the body as the stenosis or obstruction results in ‘stealing’ of blood from the opposite vertebral artery.7 Rarely, aortic valve regurgitation may result from TAK, thus echocardiographic screening is recommended. Angiography revealing obstruction with smoothly tapered stenoses is diagnostic of TAK and a biopsy is usually not necessary.8

TAK is managed with corticosteroids initially, but roughly half of patients require additional immunosuppressive treatment with thiopurines, methotrexate or mycophenolate. Refractory cases may require cyclophosphamide. Advanced or symptomatic stenoses may require percutaneous stenting or surgical bypass.9

Medium vessel vasculitis

Polyarteritis nodosa

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a systemic necrotising vasculitis of the medium-sized muscular arteries, occurring most commonly in middle-aged and older adults.10 Although most cases are idiopathic, there is a well-recognised correlation between HBV and, to a lesser extent, HCV and hairy cell leukemia.11 PAN most often affects the integumentary system and peripheral nervous system, as well as the kidneys and gastrointestinal tract. Classically, PAN spares the lungs. A case scenario outlining the assessment and treatment of a patient with PAN is summarised in Box 2.

Dermatological manifestations include erythema nodosum, livedo reticularis and generalised purpura found chiefly on the lower limbs. Renal manifestations relate to glomerular ischaemia, thus haematuria and proteinuria are typically minimal whereas renal insufficiency and hypertension prevail. Gastrointestinal symptoms include nausea, cramping, abdominal pain and melaena, as the small bowel is the most commonly affected site.12 Mononeuritis multiplex may occur from peripheral nerve involvement, in which case HIV and paraneoplastic syndromes are important differentials. Often referred to as ‘pauci-immune’ vasculitis, PAN is usually associated with negative autoantibodies including antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor.13

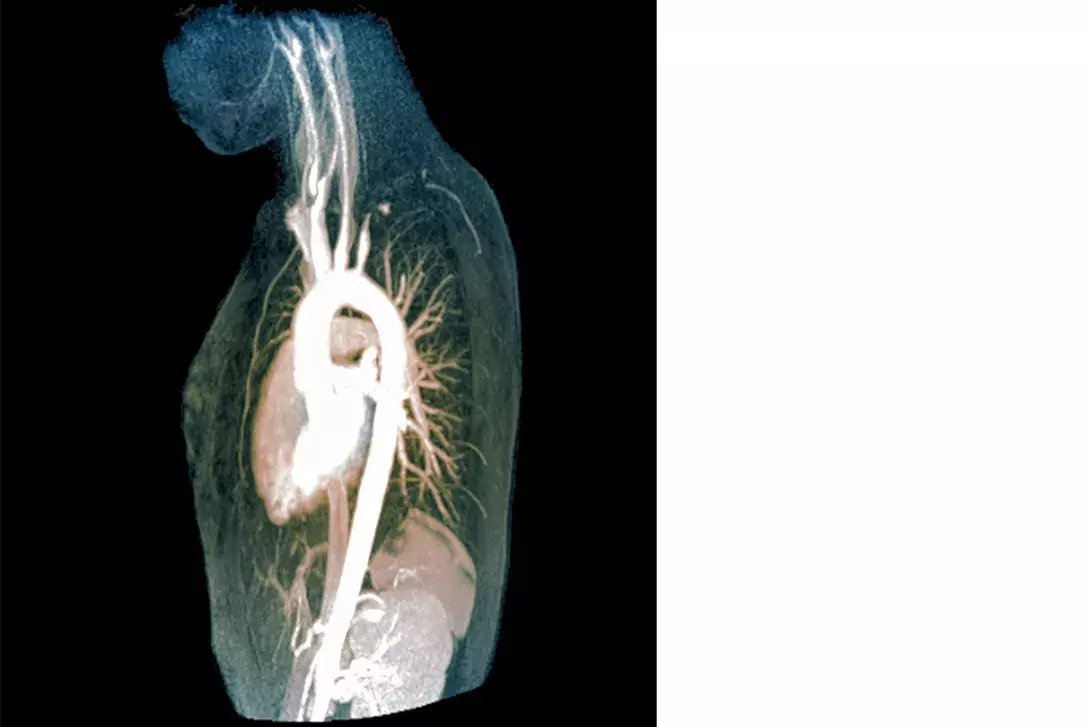

PAN can be diagnosed with CT mesenteric or renal angiography demonstrating multiple aneurysms with large vessel constriction and small vessel obstruction (Figure 2).14 A biopsy demonstrating medium-vessel necrotising inflammation is the gold standard diagnostic test and may be taken from the kidneys or sites of dermatological involvement.

Initially, PAN is managed with high-dose prednisolone for four weeks followed by a slow taper over at least six months. If steroid-sparing therapy is required, azathioprine, methotrexate, or mycophenolate mofetil are recommended. Cyclophosphamide is reserved for severe disease with proteinuria, or cardiac or central nervous system involvement.15 If viral hepatitis is present, it should be treated concomitantly.

Kawasaki disease

Kawasaki disease is a medium-vessel vasculitis that primarily affects children under the age of 5 years, most commonly in Asian populations. Cases in older children and adults are rare.16 Kawasaki disease has an infamous predilection for the coronary arteries, and unchecked inflammation can lead to coronary artery aneurysm formation, stenosis and myocardial infarction. Diagnostic criteria are based on the clinical hallmarks of the disease and require persistent fever for at least five days in addition to four of the following features:

- bilateral nonexudative conjunctivitis

- oral mucosal erythema (Figure 3)

- cervical lymphadenopathy

- polymorphous truncal rash

- erythematous desquamating rash of the hands and feet.17

Echocardiography should be performed in all suspected cases to define baseline coronary artery diameters and screen for those at high risk of obstruction. Aspirin 3 to 5 mg/kg for a minimum of six weeks and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) as a single infusion should be administered as early as possible to minimise the risk of acute obstructive coronary disease. Corticosteroids may be added in the initial phase if IVIg resistance is suspected.18 Clinical and echocardiographic follow-up is crucial for monitoring coronary risk, as this is the main long-term prognostic factor for Kawasaki disease. Recrudescent fever in the early treatment phase of this illness is the single strongest risk factor for aneurysms of the coronary arteries.19

Variable vessel vasculitis

Behçet syndrome

Behçet syndrome is a rare autoimmune systemic inflammatory vasculitis primarily affecting East Asian and Mediterranean - most commonly Turkish - populations. The disease involves both arteries and veins, and affects vessels of all sizes.20 Classical clinical manifestations of Behçet syndrome include:

- recurrent painful mucocutaneous oral and genital aphthous ulcers (Figure 4)

- ocular involvement with panuveitis and, in severe cases, retinal vasculitis

- pulmonary manifestations including arterial thrombosis and aneurysm formation with peripheral thrombophlebitis (also known as Hughes-Stovin syndrome)

- peripheral vascular disease, most commonly causing venous thrombosis

- central nervous system involvement typically manifesting as vascular thrombosis and ischaemia.

The latter two account for most disease-associated mortality in patients with Behçet syndrome.21 Arthritis, primarily asymmetric, nonerosive, nondeforming oligoarthritis of the medium-sized joints such as knees, wrists and elbows, may lead to significant morbidity and functional disability.22 Many patients with the disease display pathergy, wherein minor mucocutaneous injuries such as small lacerations or contusions (e.g. paper cuts or bumping into objects) can develop into ulcers.

No highly specific laboratory tests currently exist for Behçet syndrome, thus diagnosis is clinical.23 A combination of topical corticosteroids and colchicine is used to manage mucocutaneous lesions. Oral corticosteroids may be used for more severe or widespread dermatological disease. For persistent or refractory arthritis, treatment with azathioprine or tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors is recommended with escalation to methotrexate or interferon-alpha should these measures fail. If there is evidence of posterior uveitis or significant vascular disease, high-dose immunosuppression is indicated with systemic corticosteroids and azathioprine or another second agent. Immediate ophthalmology referral is crucial in cases of ocular disease and treatment generally consists of topical corticosteroids and dilating agents.

Cogan’s syndrome

Cogan’s syndrome is a chronic inflammatory disease primarily affecting young adults and is characterised by vestibulo-auditory dysfunction and interstitial keratitis of the eye. The most common clinical features are visual disturbance and recurrent acute attacks of vertigo, nausea, ataxia, tinnitus and sensory hearing disturbance. Progressive, long-term and profound hearing loss can occur. In a minority of cases, Cogan’s syndrome is associated with a variable-sized systemic vasculitis with a particular predilection for the aorta and is an important cause of aortitis, aortic valve regurgitation and ostial coronary artery disease.24 In addition to ophthalmological and otological examination, preliminary investigations should focus on exclusion of other causes of systemic vasculitis.

Diagnosis is clinical and based on characteristic ocular inflammation and vestibulo-auditory dysfunction. Preliminary investigations should focus on excluding other causes of systemic vasculitis. Vestibular dysfunction can be managed with benzodiazepines and antihistamines. Hearing loss is an important long-term complication that requires monitoring and referral as appropriate. Aortic and cardiac complications should be screened for at the time of diagnosis and managed appropriately. High-dose corticosteroids to induce remission, followed by a gradual taper, is the recommended initial treatment. An additional immunosuppressant such as methotrexate may be required for severe disease.25

Conclusion

The vasculitides are a diverse group of important conditions whose appearance in general practice is common. GCA is particularly pertinent in the geriatric population and portentous symptoms for visual loss are crucial to recognise and treat early to prevent blindness. Kawasaki disease is the most important vasculitis in children due to the incipient risk of coronary artery aneurysms. Behçet’s disease should be suspected in patients of Mediterranean or Turkish background who present with oral or genital ulcers, and can have highly morbid ocular and peripheral vascular complications. Specialist involvement is critical and should be obtained urgently if such complications are present. In all patients requiring long-term corticosteroids and/or immunosuppression, long-term complications including diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, hypertension, opportunistic infections and secondary malignancies require dedicated screening and management for optimal health outcomes for these patients. MT