Inhaler therapy for asthma

Inhaler therapy is effective for controlling asthma and reducing risk of exacerbations, hospitalisation and poor health outcomes, but appropriate selection of an inhaler device and correct technique in its use are essential. It is important to prescribe an inhaler device that a patient can and will use effectively and to provide patient education about asthma control, including inhaler device training and regular assessment of technique and adherence.

Note

This is an online update of the original version of this article that was published in the April 2022 issue of Respiratory Medicine Today. This update was prepared for World Asthma Day 2024.

- Despite the availability of effective therapy for controlling asthma symptoms, many people have poorly controlled asthma.

- Australian guidelines recommend a stepped approach to asthma control, starting with low-dose inhaled corticosteroids or as-needed low-dose budesonide–formoterol.

- Assessment of a patient’s inspiratory flow pattern, coordination and comorbidities can guide selection of an inhaler device.

- Adherence to inhaler therapy and inhaler device technique should be assessed regularly and before changing a patient’s therapy.

- Simplifying inhaler regimens by prescribing the same type of inhaler for concomitant inhaled medications can reduce errors in inhaler technique.

- Collaborative multidisciplinary models in primary care can help optimise health outcomes for people living with asthma.

Australia has one of the highest prevalences of asthma in the world, with one in nine Australians affected. It significantly affects quality of life, and people with asthma are less likely to report excellent health and more likely to report fair or poor health than people without asthma.1 Poorly controlled asthma is an ongoing challenge that is linked to an increased risk of exacerbations, a progressive decline in lung function and increased mortality. Although hospitalisations for asthma in Australia have plateaued over the past decade, about 80% of asthma hospitalisations are preventable.2 In 2022, there were 467 asthma-related deaths in Australia, with women aged 75 years and older accounting for 45% of all deaths.3

Despite the widespread use of asthma control guidelines and a growing number of available inhaler devices and active ingredients for controlling symptoms, many people with asthma have inadequately controlled disease and experience frequent exacerbations. Data from an Australian web-based survey showed poor symptom control in 45% of people aged 16 years or older, with 29% requiring urgent health care for their asthma in the previous 12 months.4 More than a quarter of participants described having uncontrolled symptoms and using no preventer medicine or using it only infrequently. Suboptimal adherence to preventer medication and poor inhaler technique both contribute to poorly controlled asthma.

This article provides an overview of inhaler therapy for asthma control, including the types of inhaler devices available in Australia and advice on their appropriate selection and correct technique for use.

Asthma control

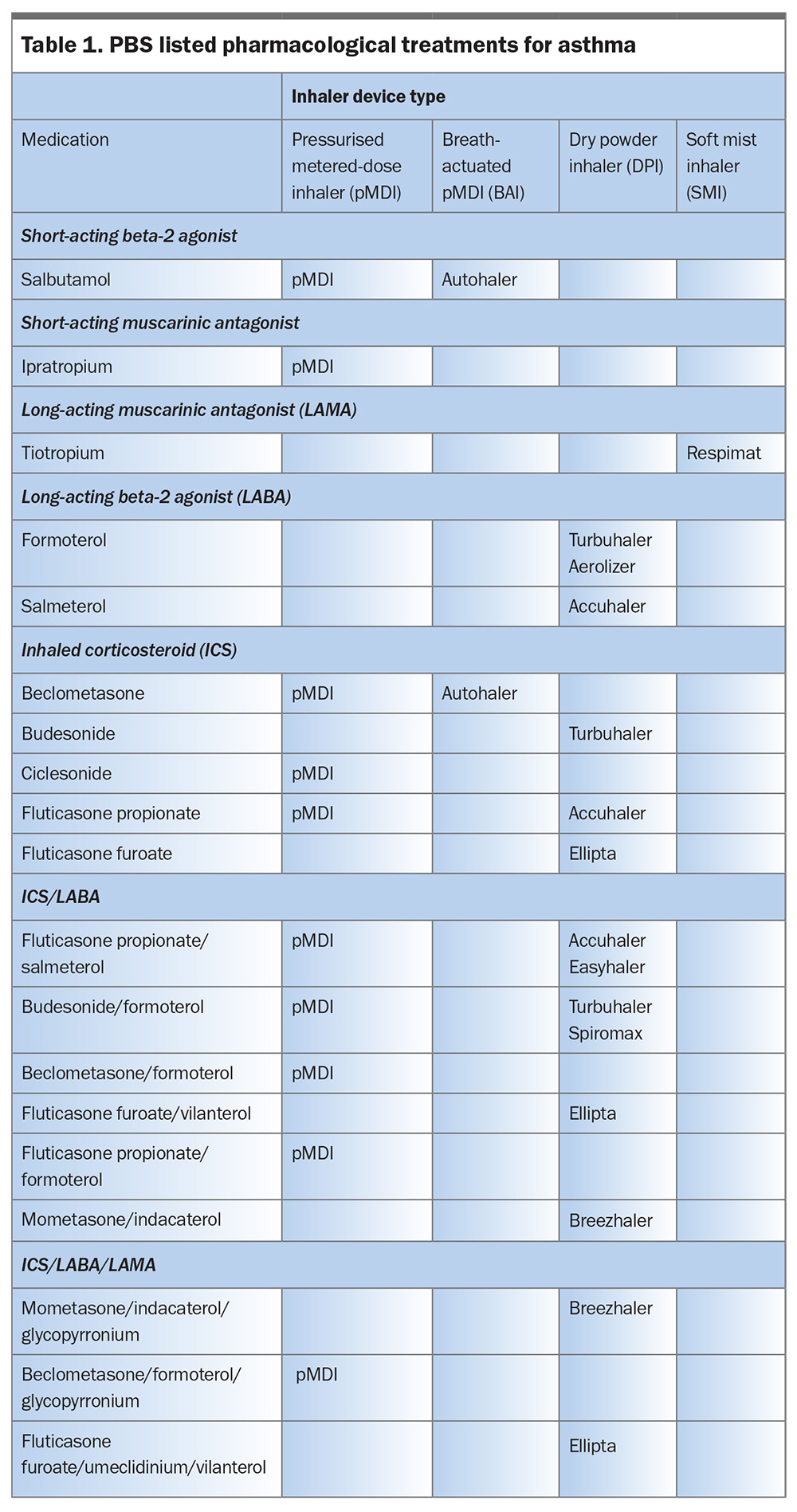

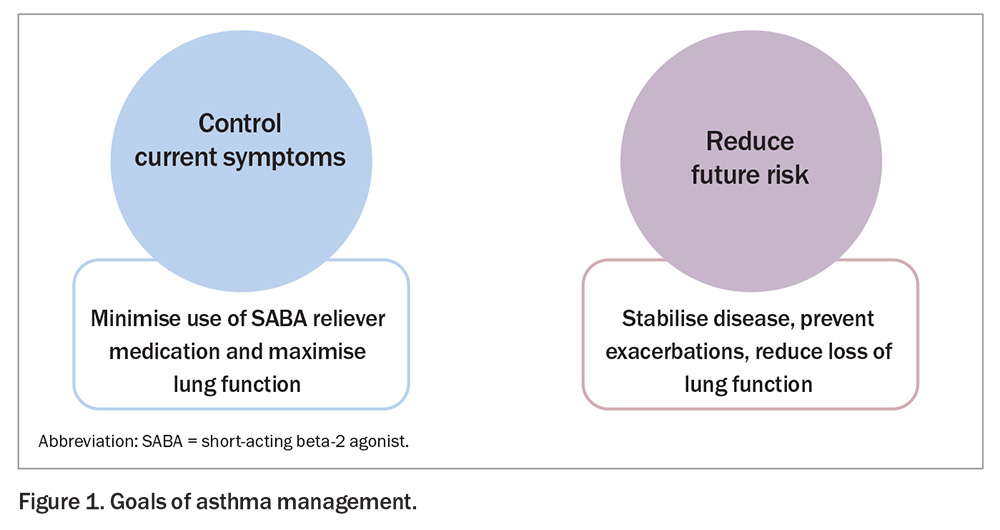

Inhaler therapy with bronchodilators (relievers) and corticosteroids (preventers) is the primary means of asthma treatment for adults, adolescents and children (Table 1). The goal of achieving overall asthma control involves two key approaches (Figure 1):

- controlling current symptoms (i.e. minimising use of reliever medication and maximising lung function)

- reducing future risk (i.e. stabilising disease, preventing exacerbations and preserving lung function over time).

These two approaches are interdependent; if current control can be achieved, future risk can be reduced. Table 2 defines levels of asthma symptom control in adults and adolescents, regardless of treatment regimen.5

Short-term relievers

Although short-acting beta-2 agonists (SABAs) provide quick relief from asthma symptoms, they have no anti-inflammatory effects and therefore do not treat the underlying cause of airway constriction. Consequently, use of SABAs alone does not prevent severe exacerbations.

Moreover, regular or frequent use of SABAs has been shown to increase the risk of near-fatal and fatal asthma exacerbations.6 Patients who are dispensed three or more SABA canisters in a year, regardless of whether they are receiving inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) treatment, have a greater risk of severe exacerbations.6 Episodes of high reliever use, defined as more than six inhalations on at least one day, also predict an increased risk of exacerbations.7 Over-reliance on SABAs and underuse of ICSs are both associated with an increase in mortality.8,9 The risk of asthma-related death is markedly increased among patients dispensed 12 or more SABA canisters in a year.10

Many patients overestimate their level of asthma control, which can lead to excessive SABA use and delayed presentation to their GP.11 Patients often erroneously perceive response to a SABA as control of their asthma. Educating patients on what constitutes good asthma control (Table 2) can support better self-management and raise awareness of the problems with over-reliance on SABAs.

Long-term control

Recent changes to international and Australian guidelines, prompted by concerns about the risks and consequences of the longstanding approach of starting asthma treatment with a SABA alone, have been described as the most fundamental change in asthma management in 30 years.12

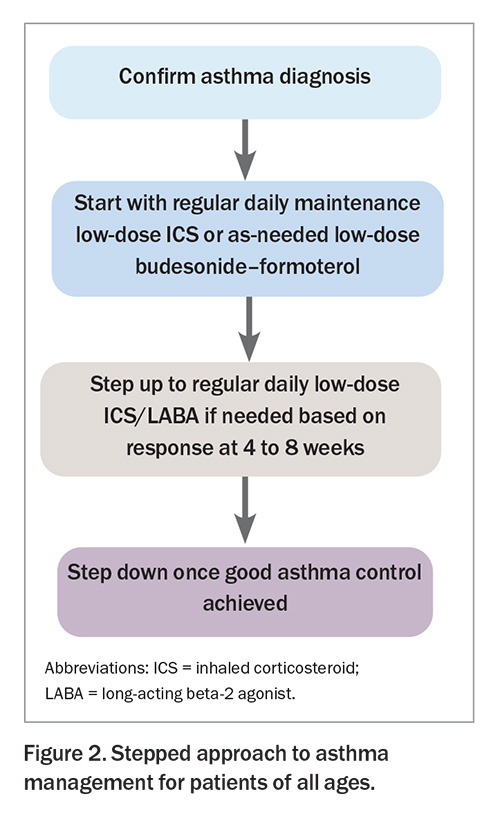

The Australian Asthma Handbook recommends a stepped approach to asthma management for patients of all ages (Figure 2).5 Every step of medication escalation requires assessment of the patient’s adherence and inhaler device technique.

For adults and adolescents, ICSs should be prescribed for patients who report any of the following:

- asthma symptoms twice or more during the past month

- waking because of asthma symptoms once or more during the past month

- an asthma flare-up that required oral corticosteroids within the previous 12 months

- history of artificial ventilation or admission to an intensive care unit because of acute asthma.5

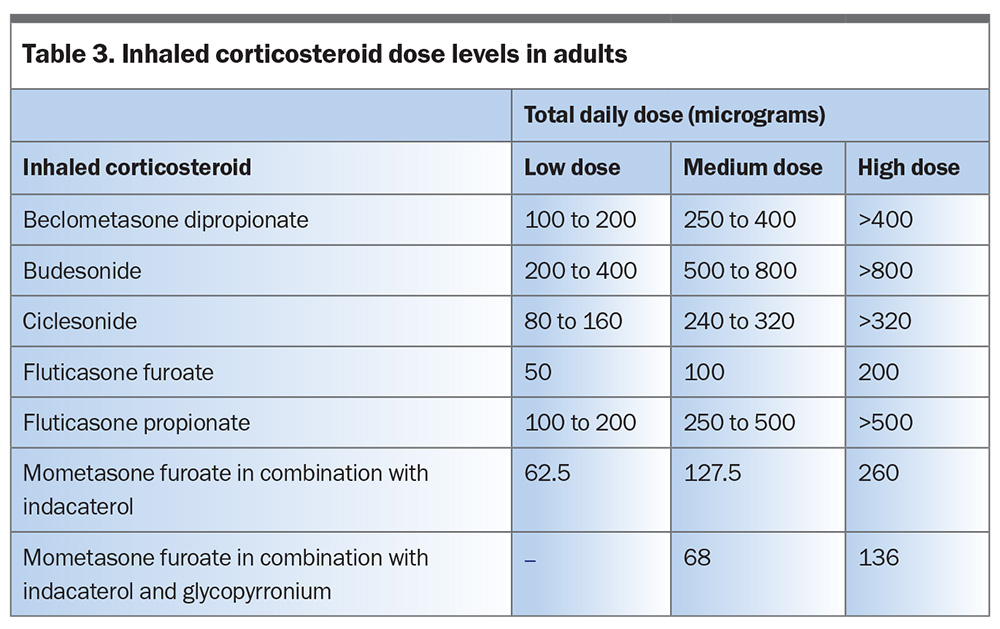

Most adults and adolescents with a confirmed and fully investigated diagnosis of asthma should start either a regular daily maintenance low-dose ICS (Table 3) or as-needed low-dose budesonide–formoterol.5 Patients should be reviewed after four to eight weeks to assess their response.5 If necessary, patients can then be stepped up to regular daily low-dose ICS/long-acting beta-2 agonist (LABA) therapy, with the view to stepping down once good asthma control is achieved.5

Maintenance and reliever therapy has the advantage of using one device. Only a few patients with asthma will require regular daily medium- to high-dose ICS/LABA therapy.5 Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) are indicated as an add-on treatment for patients with severe asthma taking an ICS-containing preventer.5

Oral corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids, such as prednisone or prednisolone, are often used to treat acute asthma exacerbations and sometimes for longer-term control. Maintenance treatment with oral corticosteroids should be avoided, if possible.5

The risk of long-term toxicity from oral corticosteroids increases with cumulative doses exceeding 1000 mg.13 This is equivalent to four or five short courses of prednisolone or prednisone. Recent analysis of PBS dispensing data showed that a quarter of asthma patients using ICSs were dispensed oral corticosteroids at cumulative doses associated with toxicity.14 Dispensing of diabetes and osteoporosis medications was more common among these patients, demonstrating an association with known adverse effects of oral corticosteroids.14 In addition, among patients dispensed 1000 mg or more of prednisolone or prednisone and using high-dose ICS preventers, adherence to preventer therapy was inadequate in more than half.14

Other treatments

Other medicines used in the treatment of asthma include montelukast, cromones and macrolide antibiotics.5 In patients with severe asthma, the use of biologic therapy (omalizumab, benralizumab, dupilumab or mepolizumab) can reduce the need for oral corticosteroid bursts and maintenance therapy, minimising the cumulative toxicity of oral corticosteroids.15,16 Mepolizumab, benralizumab and dupilumab have been shown to reduce maintenance oral corticosteroid dosing by 50 to 75%, with about 50% of patients able to discontinue oral corticosteroids.17-19 Monoclonal antibody therapies are subsidised by the PBS only when prescribed by specialists, so early referral is recommended for patients with severe allergic or eosinophilic asthma that is not controlled by high-dose ICS/LABA therapy.5

Inhaler technique

Up to 94% of patients do not use their inhaler devices correctly, resulting in inadequate dosing, suboptimal disease control, worsening of quality of life and increased hospital admissions and mortality.20 Australian data suggest that only 10% of people with asthma can competently use their inhalers.21,22 Older age, cognitive impairment, multiple different devices and lack of training are all risk factors for poor inhaler use and adherence.23 Alarmingly, many health professionals, including physicians, pharmacists and respiratory nurses, also have high rates of error in inhaler technique.24-26

Checking and correcting inhaler technique at every opportunity is essential for effective asthma management (Box).5,27 Adherence to inhaler therapy and inhaler device technique should be assessed before any dose increase or change in therapy.5 Repeated instruction in inhaler technique can improve adherence to therapy and asthma outcomes.5,28,29

Right device, right patient

With several different types of inhaler devices available, choosing the right device for each patient is crucial to ensuring correct technique and improving the likelihood of good adherence to therapy.30 Inhaler devices vary widely by technique, patient suitability and patient preference.30 No one device is considered the easiest to use or preferred for daily use, highlighting that the choice of inhaler must be considered individually.31 It is important to prescribe an inhaler device that the patient can and will use effectively.

Device-specific factors

Inhaler devices can be grouped into:

- pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs)

- breath-actuated pMDIs (BAIs)

- dry powder inhalers (DPIs)

- soft mist inhalers (SMIs).

Lung deposition of the active ingredient depends on the type of device, aerosol formulation and the patient’s inhalation technique. The internal device resistance, aerosol duration, particle size and aerosol velocity all need to be considered in the choice of inhaler device.32 The delivery system of an inhaler generates an aerosol cloud containing particles that can penetrate the respiratory tract and small airways.

Particle size is important, as particles too small may be exhaled, while those that are too large experience inertial impaction in the oropharynx and large airways.33 Inhaled medicines with a small particle size (beclometasone, ciclesonide) may achieve a greater proportion of medicine deposited in the lungs.5

Aerosol particle spray velocity also influences the degree of lung deposition and impaction in the oropharynx. For example, the slower plume velocity, high fine-particle fraction and longer spray duration of SMIs results in higher lung deposition than with pMDIs.34

Patient-specific factors

Determining a patient’s inspiratory flow rate can help with choosing an inhaler device, as the inspiratory flow rate varies between devices.35 pMDIs and SMIs require the least inspiratory effort, whereas DPIs rely on a patient’s ability to produce sufficient airflow to cause deagglomeration of the active ingredient from the excipient powder. The inspiratory flow rate for pMDIs, BAIs and SMIs should be slow, steady and deep over three to five seconds for adults and two to three seconds for children to minimise deposition in the upper airways and enhance delivery to the lungs.36 On the other hand, DPIs require a quick and deep inhalation.36 A faster inspiratory flow rate will produce significantly greater lung deposition than a slower inspiratory flow rate.36 Assessing whether a patient is more likely to master the fast, sharp inhalation required by DPIs or the slow, even inhalation required by pMDIs and SMIs can therefore guide device selection (Figure 3).37

Patient satisfaction with and preference for a particular inhaler device may lead to improved adherence and better asthma outcomes.38 Older patients, especially those with cognitive decline, may find more complex manoeuvres challenging. Physical issues, including weakness, impaired dexterity, declining vision, poor hearing and low inspiratory rate, may affect a patient’s ability to use a device. Comorbidities, such as obesity or respiratory muscle weakness and ageing, can negatively affect inspiratory flow rate and may cause the patient to have difficulty using a particular device. Health literacy or language barriers can also influence device use by inhibiting a patient’s ability to understand inhaler instructions.39

Some patient-related questions to consider when selecting an inhaler device are:

- Do they have sufficient hand–breath co-ordination?

- Are they able to form a good seal over the mouthpiece?

- Are they able to open, manipulate and prime the device?

- Are they able to inhale at the correct speed?

Inhaler simplification

One of the challenges for patients in using multiple inhaler devices is remembering and mastering the different steps for each inhaler type. Patients prescribed one or more inhaler devices requiring a similar inhalation technique show better outcomes than those prescribed multiple devices requiring different techniques.40

Simplifying a patient’s inhaler regimen by prescribing the same type of inhaler for concomitant inhaled medications can minimise device misuse, leading to improved clinical outcomes and reduced health care use.41 Consistent use of the same type of device may be associated with better technique, adherence and persistence. Once a patient is familiar with one type of inhaler, it is preferable to prescribe the same type of inhaler if therapy is stepped up. Switching to new devices requires training at the prescribing and dispensing stages.36

Prescribing multiple-inhaler triple therapy (ICS/LABA/LAMA) for patients with asthma is associated with a substantial disease and health care burden and higher exacerbation rates.42 The growing availability of dual- and triple-combination inhalers in a single device allows simplification of inhaler regimens.

Multidisciplinary approach

It has been shown that a shared-care approach and comprehensive patient education, including inhaler device training, can improve clinical outcomes.43 Pharmacists conducting medication reviews can address patient beliefs, attitudes and preferences about inhaler use, as well as checking the patient’s inhaler device technique. The integration of pharmacists into general practices, working in collaboration with GPs, can improve asthma outcomes for patients.44 A pilot study in a general practice in Canberra showed that it is feasible, acceptable and potentially beneficial to have a general practice pharmacist involved in asthma management.45 The most common activities undertaken by the general practice pharmacist were asthma control assessment, recommendations to adjust medication or device, counselling on correct device use, asthma action plan development and trigger avoidance.45

Conclusion

Optimal management of asthma requires a stepped approach to pharmacotherapy, with regular assessment of adherence to therapy and inhaler device technique. Different inhaler devices require different techniques. Several device-specific and patient-specific factors influence whether a patient is capable of carrying out each step of the inhaler technique correctly. Ensuring that patients are comfortable with their inhaler device can improve adherence to treatment, leading to better control of their asthma. RMT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: first results 2017–18. ABS Cat No. 4364.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS; 2018.

2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Separation statistics by principal diagnosis (ICD-10-AM 10th edition), Australia 2017–18. Canberra: AIHW; 2019.

3. National Asthma Council Australia. Asthma mortality data. 2022 Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Asthma Council Australia, 2024. Available online at: https://www.nationalasthma.org.au/living-with-asthma/resources/health-professionals/infographics/asthma-mortality-statistics-2022 (accessed May 2024).

4. Reddel HK, Sawyer SM, Everett PW, Flood PV, Peters MJ. Asthma control in Australia: a cross-sectional web-based survey in a nationally representative population. Med J Aust 2015; 202: 492-498.

5. National Asthma Council Australia. Australian Asthma Handbook, version 2.1. Melbourne: National Asthma Council Australia; 2020. Available online at: https://www.asthmahandbook.org.au (accessed March 2022).

6. Amin S, Soliman M, McIvor A, Cave A, Cabrera C. Usage patterns of short-acting β2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids in asthma: a targeted literature review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8: 2556-2564.

7. Buhl R, Kuna P, Peters MJ, et al. The effect of budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever therapy on the risk of severe asthma exacerbations following episodes of high reliever use: an exploratory analysis of two randomised, controlled studies with comparisons to standard therapy. Respir Res 2012; 13: 59.

8. Suissa S, Ernst P, Boivin JF, et al. A cohort analysis of excess mortality in asthma and the use of inhaled beta-agonists. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994; 149: 604-610.

9. Suissa S, Ernst P, Benayoun S, Baltzan M, Cai B. Low-dose inhaled corticosteroids and the prevention of death from asthma. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 332-336.

10. Nwaru BI, Ekström M, Hasvold P, Wiklund F, Telg G, Janson C. Overuse of short-acting β2-agonists in asthma is associated with increased risk of exacerbation and mortality: a nationwide cohort study of the global SABINA programme. Eur Respir J 2020; 55: 1901872.

11. Price D, David-Wang A, Cho SH, et al. Time for a new language for asthma control: results from REALISE Asia. J Asthma Allergy 2015; 8: 93-103.

12. Reddel HK, FitzGerald JM, Bateman ED, et al. GINA 2019: a fundamental change in asthma management. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1901046.

13. Blakey J, Chung LP, McDonald VM, et al. Oral corticosteroids stewardship for asthma in adults and adolescents: a position paper from the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand. Respirology 2021; 26: 1112-1130.

14. Hew M, McDonald VM, Bardin PG, et al. Cumulative dispensing of high oral corticosteroid doses for treating asthma in Australia. Med J Aust 2020; 213: 316-320.

15. Chung LP, Upham JW, Bardin PG, Hew M. Rational oral corticosteroid use in adult severe asthma: a narrative review. Respirology 2020; 25: 161-172.

16. Cataldo D, Louis R, Michils A, et al. Severe asthma: oral corticosteroid alternatives and the need for optimal referral pathways. J Asthma 2021; 58: 448-458.

17. Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al; SIRUS Investigators. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1189-1197.

18. Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al; ZONDA Trial Investigators. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of benralizumab in severe asthma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 2448-2458.

19. Rabe KF, Nair P, Brusselle G, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in glucocorticoid-dependent severe asthma. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 2475-2485.

20. Lavorini F, Magnan A, Dubus JC, et al. Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med 2008; 102: 593-604.

21. Bosnic-Anticevich SZ, Sinha H, So S, Reddel HK. Metered-dose inhaler technique: the effect of two educational interventions delivered in community pharmacy over time. J Asthma 2010; 47: 251-256.

22. Saini B, LeMay K, Emmerton L, et al. Asthma disease management-Australian pharmacists’ interventions improve patients’ asthma knowledge and this is sustained. Patient Educ Couns 2011; 83: 295-302.

23. Usmani OS, Lavorini F, Marshall J, et al. Critical inhaler errors in asthma and COPD: a systematic review of impact on health outcomes. Respir Res 2018; 19: 10.

24. Swami V, Cho J, Smith T, Wheatley J, Roberts M. Confidence of nurses with inhaler device education and competency of device use in a specialised respiratory inpatient unit. Chron Respir Dis 2021; 18: 14799731211002241.

25. Nguyen YBN, Wainwright C, Basheti IA, Willis M, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Do health professionals on respiratory wards know how to use inhalers? J Pharm Pract Res 2010; 40: 211-216.

26. Plaza V, Giner J, Rodrigo GJ, Dolovich MB, Sanchis J. Errors in the use of inhalers by health care professionals: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6: 987-995.

27. Scullion J, Fletcher M. Inhaler standards and competency document. UK Inhaler Group; 2019. Available online at: https://www.ukinhalergroup.co.uk/uploads/s4vjR3GZ/InhalerStandardsMASTER.docx2019V10final.pdf (accessed March 2022).

28. Basheti IA, Reddel HK, Armour CL, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Improved asthma outcomes with a simple inhaler technique intervention by community pharmacists. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119: 1537-1538.

29. Takemura M, Kobayashi M, Kimura K, et al. Repeated instruction on inhalation technique improves adherence to the therapeutic regimen in asthma. J Asthma 2010; 47: 202-208.

30. Dekhuijzen R, Lavorini F, Usmani OS, van Boven JFM. Addressing the impact and unmet needs of nonadherence in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: where do we go from here? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6: 785-793.

31. Chorão P, Pereira AM, Fonseca JA. Inhaler devices in asthma and COPD – an assessment of inhaler technique and patient preferences. Respir Med 2014; 108: 968-975.

32. Usmani OS. Choosing the right inhaler for your asthma or COPD patient. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2019; 15: 461-472.

33. Capstick T, Clifton IJ. Inhaler technique and training in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Expert Rev Respir Med 2012; 6: 91-103.

34. Hochrainer D, Hölz H, Kreher C, Scaffidi L, Spallek M, Wachtel H. Comparison of the aerosol velocity and spray duration of Respimat Soft Mist inhaler and pressurized metered dose inhalers. J Aerosol Med 2005; 18: 273-282.

35. Usmani OS, Capstick T, Saleem A, Scullion J. Choosing an appropriate inhaler device for the treatment of adults with asthma or COPD. Available online at: https://www.guidelines.co.uk/respiratory/inhaler-choice-guideline/455503.article (accessed March 2022).

36. Laube BL, Janssens HM, de Jongh FHC, et al. What the pulmonary specialist should know about the new inhalation therapies. Eur Respir J 2011; 37: 1308-1331.

37. Papi A, Haughney J, Virchow JC, Roche N, Palkonen S, Price D. Inhaler devices for asthma: a call for action in a neglected field. Eur Respir J 2011; 37: 982-985.

38. Anderson P. Patient preference for and satisfaction with inhaler devices. Eur Respir Rev 2005; 14: 109-116.

39. Apter AJ, Wan F, Reisine S, et al. The association of health literacy with adherence and outcomes in moderate-severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132: 321-327.

40. Bosnic-Anticevich S, Chrystyn H, Costello RW, et al. The use of multiple respiratory inhalers requiring different inhalation techniques has an adverse effect on COPD outcomes. Intl J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017; 12: 59-71.

41. Usmani OS, Hickey AJ, Guranlioglu D, et al. The impact of inhaler device regimen in patients with asthma or COPD. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 3033-3040.

42. Oppenheimer J, Bogart M, Bengtson LGS, et al. Treatment patterns and disease burden associated with multiple-inhaler triple-therapy use in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10: 485-494.e5.

43. Price D, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Briggs A, et al; Inhaler Error Steering Committee. Inhaler competence in asthma: common errors, barriers to use and recommended solutions. Respir Med 2013; 107: 37-46.

44. Qazi A, Saba M, Armour C, Saini B. Perspectives of pharmacists about collaborative asthma care model in primary care. Res Social Adm Pharm 2021; 17: 388-397.

45. Deeks LS, Kosari S, Boom K, et al. The role of pharmacists in general practice in asthma management: a pilot study. Pharmacy (Basel) 2018; 6: 114.