Constipation in older people – an update

Constipation is a common condition. Although its cause is benign in most cases, it can have a significant impact on an individual’s quality of life. Older people are predisposed to constipation because of immobility, polypharmacy and comorbidities.

Constipation is a common yet often debilitating condition that disproportionately affects older patients. Women are 2.2 times more likely than men to experience constipation.1 The term constipation often refers to reduced stool frequency or hard stools, but other common symptoms include excess straining, incomplete emptying or a sense of blockage. The prevalence of constipation varies, depending on the definition, from 24 to 59% of adults aged 18 years or older.1 Among older people in residential care facilities, the prevalence of constipation is higher, with up to 67% of nursing home residents using laxatives.2 In a recent large trinational community-based survey using Rome IV criteria, the prevalence of bowel disorders was 22.3% in participants aged 65 years or older.3

Many patients self-manage their constipation. An Australian study of community-dwelling adults aged 18 years or older reported that 37% self-medicated with laxatives, yet only 13% sought medical consultation for the management of their constipation.1 Nearly half of patients (42%) report being ‘frustrated’ with constipation, and 59% are unsatisfied with their treatment.4 Most patients can be satisfactorily managed in general practice, with a minority subsequently referred to gastroenterologists.

Classification

Chronic constipation can be classified according to physiology, which can guide further therapy. Slow transit constipation involves a delay in the passage of content through the colon, whereas dyssynergic defaecation (often termed a defaecatory disorder) is where there is difficulty with evacuating stool from the rectum. These two types of constipation often coexist. Patients with normal transit constipation, on the other hand, may have more sensory than motor dysfunction and might have irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Causes

Age-related physiological changes make the older population more prone to constipation. The number of excitatory neurons and glial cells, specifically in the lower gastrointestinal tract, decreases with increasing age, leading to reduced colonic motility.5 This is compounded by weakening of abdominal and pelvic floor muscles and reduced rectal sensation further affecting the defaecation process. Besides these physiological changes, there are external factors in the older population that contribute to constipation, including immobility, malnutrition and poor diet, comorbidities and polypharmacy.6,7

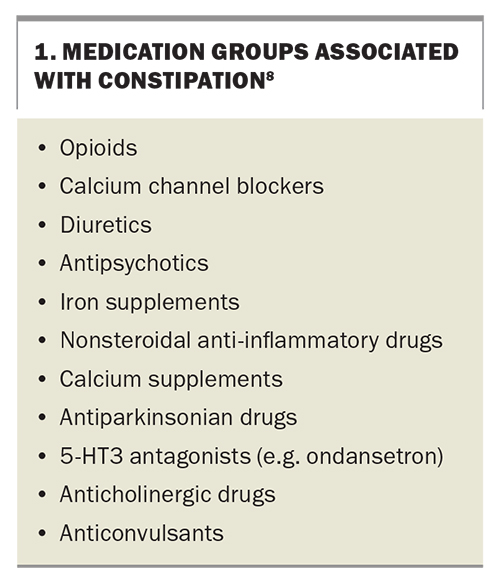

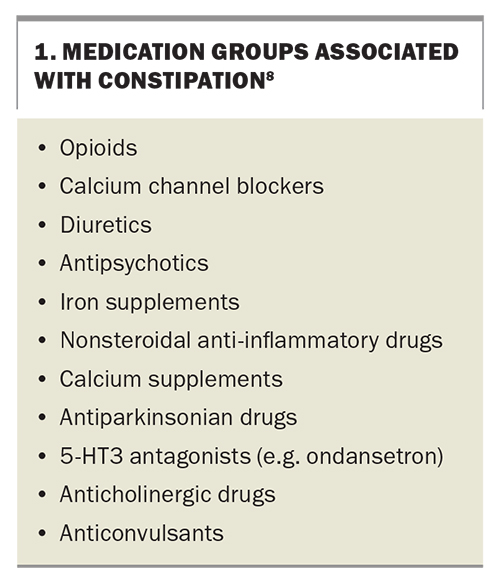

Medications such as opioids, iron supplements, calcium channel blockers, diuretics and tricyclic antidepressants are well-known contributors to constipation (Box 1).8 Patients who have constipation while taking opioids are specifically classified as having ‘opioid-induced constipation’. Metabolic conditions and endocrinopathies such as hypercalcaemia, hypothyroidism and coeliac disease can contribute to constipation.9 Patients with neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease, stroke and diabetes, are more likely to have constipation, and these conditions are more prevalent among older people.

Clinical evaluation

History and examination are key to the successful management of constipation. It is crucial to identify exactly what the patient means by the word ‘constipation’ and which symptoms are the most burdensome for the patient. The three most common constipation symptoms identified by community-dwelling Australian adults are incomplete evacuation, straining and hard stool consistency.1 In older patients, straining is the most prevalent symptom.10 Hard or infrequent stools are perhaps the most classic symptoms of constipation; yet straining, incomplete emptying, digitation, sense of blockage and prolonged toileting time may suggest a defaecatory disorder. A stool diary can provide a clearer picture of the patient’s condition and is more accurate than patient recall.11

The anorectal examination is an important step in assessing the cause and severity of constipation. It is important to note any finding of a rectocoele, rectal prolapse, anal fissure, haemorrhoids or signs of a defaecatory disorder (e.g. paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter with strain). A malignant anorectal mass may be detected during an anorectal examination. If there is rectal impaction with stool, this will direct therapy to include enemas and suppositories.

Investigations

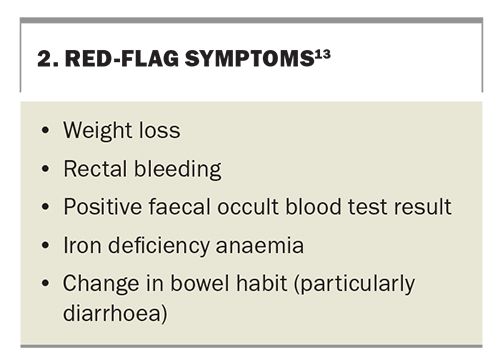

Although constipation alone does not increase the risk of colorectal cancer in the long term, it is important to exclude colorectal cancer as a possible diagnosis.12 Red flag symptoms, such as rectal bleeding, weight loss and iron deficiency anaemia (Box 2), should be further investigated, including with colonoscopy where appropriate.13 Patients should be encouraged to participate in age-appropriate colorectal cancer screening according to their individual risk (e.g. with faecal occult blood testing or with colonoscopy if there is a family history or previous polyps).14

A full blood count and iron studies are useful to screen for iron deficiency anaemia, which would be a stimulus for further examination and an urgent referral to a gastroenterologist. Patients should be screened for coeliac disease, especially if IBS symptoms coexist.15 Other blood tests that are sometimes performed include thyroid function, calcium level, inflammatory markers and diabetes testing.

Abdominal x-ray is sometimes used to assess faecal loading and guide therapy but is not essential. Nuclear medicine colonic transit studies and sitz marker studies are more advanced tests assessing colonic motility and are used to identify slow transit constipation. Severe slow transit is an indication for colectomy in rare cases.

A defaecating proctogram is used to assess for a defaecatory disorder. A contrast-enhanced simulated stool (e.g. barium paste) is expelled over a commode during dynamic imaging (e.g. fluoroscopy or MRI). This provides useful information about the anatomy and the degree of rectal emptying. Patient embarrassment may be a significant deterrent. However, it may be appropriate to perform this test, especially for patients in whom biofeedback therapy fails and who may be surgical candidates.16

Anorectal manometry uses a thin catheter with multiple pressure ports to measure rectal and anal pressures during simulated defaecation, as well as assessing rectal sensation. It can give detailed information about whether there is effective co-ordination between the rectum and anal canal during defaecation and guides selection of patients who might benefit from anorectal biofeedback therapy. The test to expel a rectal balloon filled with water, which simulates defaecation, should also be performed.17

Management

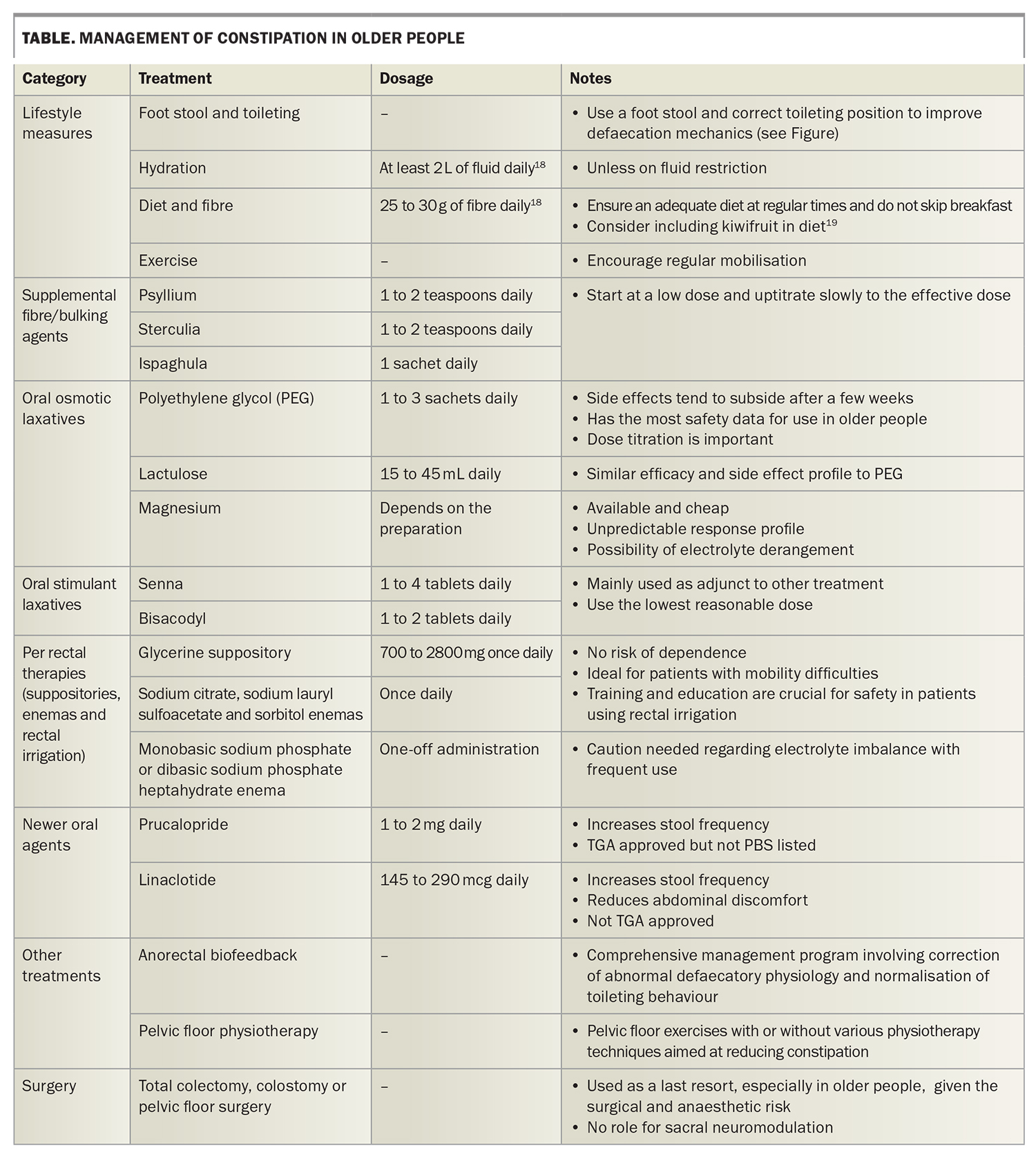

Management options are summarised in the Table.

Lifestyle

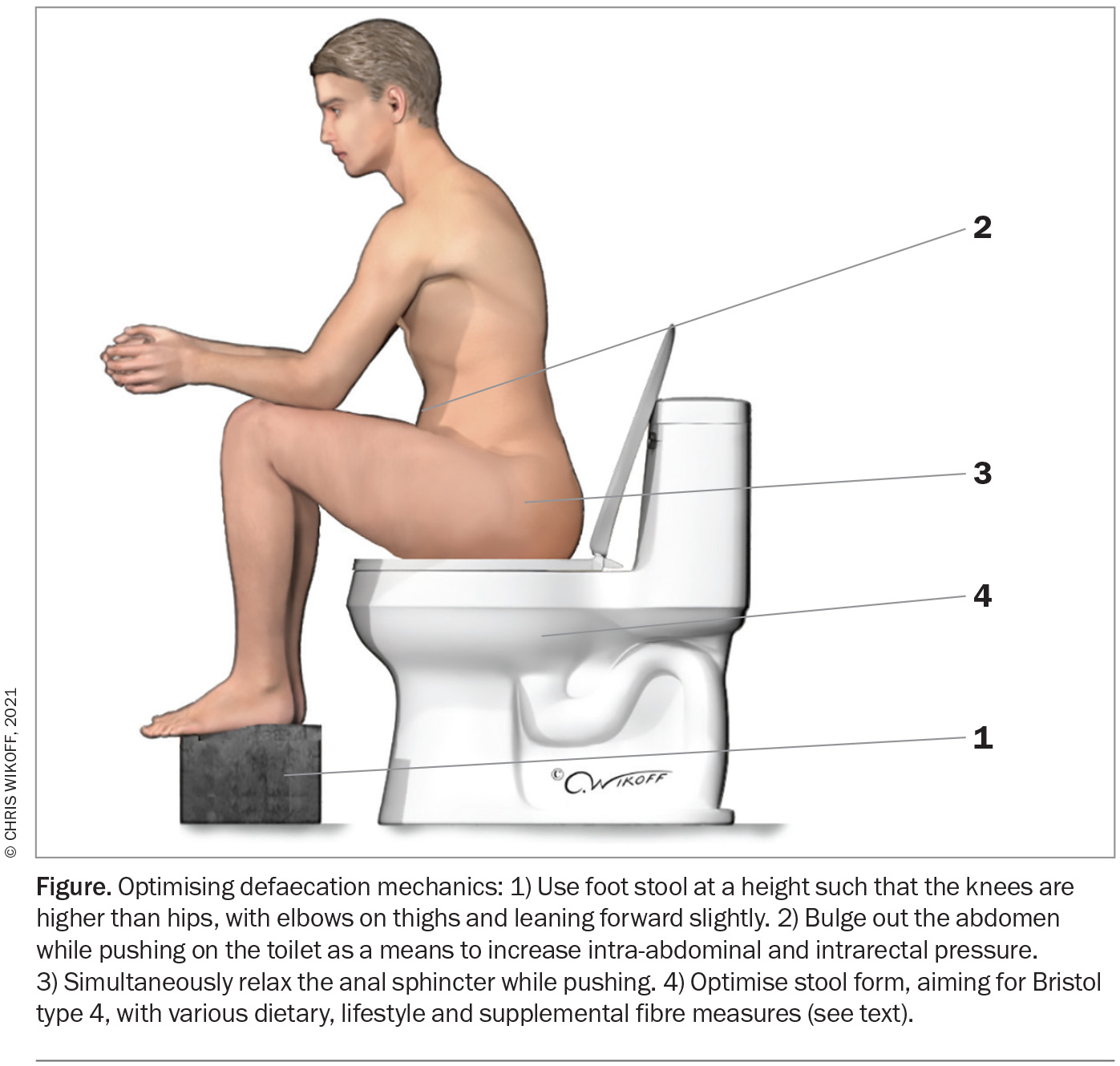

Lifestyle measures that may be helpful in constipation management include promoting good sleep, light exercise, good hydration and dietary manipulation.20 Educating patients about correct toileting position and behaviour with the use of a footstool may also reduce constipation and difficulty of evacuation (Figure).16

Having adequate caloric intake at regular intervals is important to make use of the gastrocolonic response. Dietary fibre helps optimise stool consistency; the recommended daily fibre intake is 25 to 30 g.18 It is important to gradually uptitrate fibre intake to minimise undesirable side effects. A recent randomised controlled trial showed that, compared with a control arm receiving dietary fibre through psyllium, consumption of two kiwifruits daily increased stool frequency and reduced abdominal symptoms. The daily amount of fibre given to the control arm (7.5 g) was, however, much lower than the recommended daily intake.19

It is important to review patients’ medication lists to identify any medications that may cause constipation, which should be stopped or reduced if possible (Box 1). Polypharmacy is common in older people.

Laxatives

Laxative choice needs to be individualised based on predominant symptoms and the clinical situation. Laxatives need to be titrated according to their effect, and they may be used in combination.

Supplemental fibre (bulk laxative)

Psyllium is the most well-studied bulk laxative. It is useful in improving stool frequency but is not effective in reducing other defaecation symptoms.6 Sterculia is a very useful alternative.

Osmotic laxatives

Osmotic laxatives include lactulose, sorbitol, magnesium and polyethylene glycol (PEG). They soften the stool by increasing intraluminal water transfer, enhancing colonic motility and decreasing stool transit time. Lactulose significantly increases defaecation frequency and reduces the need for other laxatives.6 PEG is the most widely used osmotic laxative. In a randomised controlled trial of PEG versus placebo, 52% of patients receiving PEG, compared with 11% of a placebo group, achieved a composite outcome of reduced use of rescue laxatives and reduced constipation symptoms.21

As with fibre, careful titration of PEG is important to reduce bloating and abdominal discomfort. This minimises the development of side effects and prevents faecal incontinence from overtreatment.20 There is no significant difference in efficacy or side effects of lactulose compared with PEG.6 Thus, the choice between the two can be based on patient preference and individual response.

Magnesium is an alternative osmotic laxative and is relatively cheap and easily accessible in the form of Epsom salts. It is sometimes the active component of herbal laxatives. An unpredictable response profile and undesirable adverse effects, such as hypermagnesaemia, are the main concerns with magnesium. Therefore, it is not recommended as the first-line therapy.

Stimulant laxatives and stool softeners

Stimulant laxatives include senna, cascara, bisacodyl and herbal medications. It can be difficult to identify stimulant laxatives when they are present in herbal supplements and teas. They work by stimulating high-amplitude propagating contractions and may cause abdominal pain.

There are limited safety data for use of stimulant laxatives in older people. Based on clinical experience, they are best used at the lowest possible dose as an adjunct to other laxatives.20 Possible side effects, such as cathartic colon, are only evident after more than 20 years of use and are therefore of less concern in the older population.22

Stool softeners such as docusate sodium are often prescribed, but evidence for their efficacy is limited. Using a fibre supplement is the preferred approach.

Suppositories and enemas

Per rectal therapy, such as suppositories (e.g. glycerine) or enemas (e.g. sodium citrate, sodium lauryl sulfoacetate and sorbitol), can give patients control over the timing and efficacy of defaecation. These modalities are especially useful in those with limited mobility. They are also available in stimulant laxative preparations. However, phosphate-containing enemas may cause hyperphosphataemia, especially in patients with renal failure, and should be used cautiously.23 Transanal rectal irrigation can be used for more severe cases of constipation, patients with faecal impaction and patients with neurogenic bowel. Patients must be properly educated on how to safely perform this treatment to avoid rare complications, such as perforation.24

Novel agents

Prucalopride is a selective agonist of serotonin 5-HT4. It is available in Australia but not PBS listed. Compared with a control group in a randomised controlled trial, a higher proportion of patients taking prucalopride for 12 weeks achieved three or more spontaneous bowel movements weekly.25 This was not replicated in a European study in 2015, but the latter study had a higher withdrawal rate.26 There were no significant adverse events, such as cardiac arrhythmia or QT interval prolongation, even in older people.27 Headache is a common treatment-limiting side effect of prucalopride.27 Suicide and suicidal ideations, either while taking or after stopping prucalopride, have been reported. Although no definite association has been established, the United States Food and Drug Administration recommends ongoing monitoring for depression and suicidality while patients are receiving treatment.

There are other agents for treating constipation, such as linaclotide, lubiprostone, plecanitide and elobixibat. Linaclotide has limited approval for import and supply, but the others are not approved in Australia. Lubiprostone, linaclotide and plecanitide are secretory drugs. Elobixibat is an inhibitor of the ileal bile acid transporter, which increases water secretion by epithelial cells in the large colon and is contraindicated in patients who have had a cholecystectomy. These agents have all been shown to increase spontaneous bowel motions without significant cardiac side effects.6 Linaclotide has also been shown to be effective in relieving abdominal discomfort.28

Massage

Abdominal massage has been investigated as a treatment of constipation, particularly in older patients in hospitals and nursing homes. Five randomised controlled trials have suggested benefit, but varying study methods and outcomes make it difficult to draw firm conclusions from these.29-33

Biofeedback or pelvic floor physiotherapy

Biofeedback therapy is a multifaceted treatment that focuses on improving defaecation using education, exercises and visual (or other) feedback regarding a patient’s own physiology. It may also involve sensory retraining and balloon expulsion retraining. Response rates for patients with constipation are about 70 to 80%.34

Pelvic floor physiotherapy involves various exercises to strengthen and improve the coordination of pelvic floor muscles, often without visual feedback. It is less standardised than biofeedback therapy, and its results are scarcely reported in the literature. Nonetheless, it may be a reasonable alternative when access to anorectal biofeedback is difficult.

Surgery

If there is a structural abnormality affecting defaecation, such as a large, nonemptying rectocoele, constipation may resolve with surgical correction. However, all conservative measures should be employed first. Surgically correcting pelvic floor anatomy does not always lead to a reduction in symptoms. For patients with severe slow transit constipation, surgical options include total colectomy, segmental colectomy, loop ileostomy and ileorectal anastomosis. Although these surgeries treat constipation, they may also cause new gastrointestinal symptoms or recurrent bowel obstruction (in 15% of patients).35 Surgery in older patients generally carries a higher degree of risk and is therefore only rarely recommended. Unlike for faecal incontinence, there is no role for sacral nerve stimulation for treating constipation.16

Conclusion

The cause of constipation in older people is multifactorial. It is important to identify patients with red flag symptoms and refer these patients for specialist assessment. For most patients, simple lifestyle adjustments, including dietary changes and improving hydration, may be helpful. There are multiple laxative options, with the osmotic laxative PEG having the most evidence to support its efficacy and safety for older patients. Per rectal treatment (such as enemas) may be particularly useful in older people with limited mobility. Patients with refractory constipation caused by a defaecatory disorder may benefit from anorectal biofeedback therapy or pelvic floor physiotherapy. Surgery is only rarely required. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Werth BL, Williams KA, Fisher MJ, Pont LG. Defining constipation to estimate its prevalence in the community: results from a national survey. BMC Gastroenterol 2019; 19: 75.

2. Blekken LE, Nakrem S, Vinsnes AG, et al. Constipation and laxative use among nursing home patients: prevalence and associations derived from the Residents Assessment Instrument for Long-Term Care Facilities (interRAI LTCF). Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016; 2016: 1215746.

3. Palsson OS, Whitehead W, Tornblom H, Sperber AD, Simren M. Prevalence of Rome IV functional bowel disorders among adults in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1262-1273.e3.

4. Harris LA, Horn J, Kissous-Hunt M, Magnus L, Quigley EMM. The Better Understanding and Recognition of the Disconnects, Experiences, and Needs of Patients with Chronic Idiopathic Constipation (BURDEN-CIC) Study: results of an online questionnaire. Adv Ther 2017; 34: 2661-2673.

5. Nguyen VTT, Taheri N, Chandra A, Hayashi Y. Aging of enteric neuromuscular systems in gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2022; 34: e14352.

6. Kang SJ, Cho YS, Lee TH, et al. Medical management of constipation in elderly patients: systematic review. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021; 27: 495-512.

7. Wald A, Scarpignato C, Mueller-Lissner S, et al. A multinational survey of prevalence and patterns of laxative use among adults with self-defined constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008; 28: 917-930.

8. Mari A, Mahamid M, Amara H, Baker FA, Yaccob A. Chronic constipation in the elderly patient: updates in evaluation and management. Korean J Fam Med 2020; 41: 139-145.

9. Hungin AP. Chronic constipation in adults: the primary care approach. Dig Dis 2022; 40: 142-146.

10. Whitehead WE, Drinkwater D, Cheskin LJ, Heller BR, Schuster MM. Constipation in the elderly living at home. Definition, prevalence, and relationship to lifestyle and health status. J Am Geriatr Soc 1989; 37: 423-429.

11. Hudgi A, Yan Y, Ayyala D, Inman B, Sharman A, Rao S. Evaluation of the accuracy of patient’s recall of bowel symptoms compared to a prospective stool diary in patients with chronic constipation. In: Proceedings of Digestive Disease Week; 2022 May 21-24; San Diego, USA.

12. Staller K, Olen O, Soderling J, et al. Chronic constipation as a risk factor for colorectal cancer: results from a nationwide, case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 20: 1867-1876.e2.

13. Ewing M, Naredi P, Zhang C, Mansson J. Identification of patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer in primary care: a case-control study. Br J Gen Pract 2016; 66: e880-e886.

14. Cancer Council Australia Colorectal Cancer Guidelines Working Party. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention, early detection and management of colorectal cancer. Sydney: Cancer Council Australia; 2018. Available online at: https://wiki.cancer.org.au/australia/Guidelines:Colorectal_cancer (accessed March 2023).

15. Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 656-676; quiz 677.

16. Wald A, Bharucha AE, Limketkai B, et al. ACG clinical guidelines: management of benign anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol 2021; 116: 1987-2008.

17. Carrington EV, Heinrich H, Knowles CH, et al. The international anorectal physiology working group (IAPWG) recommendations: standardized testing protocol and the London classification for disorders of anorectal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2020; 32: e13679.

18. National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian dietary guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC; 2013.

19. Gearry R, Fukudo S, Barbara G, et al. Consumption of two green kiwifruits daily improves constipation and abdominal comfort—results of an international multicenter randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jan 9. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002124. Online ahead of print.

20. Malcolm A. Constipation. How to get started. Medicine Today 2021; 22(1-2): 48-55.

21. Dipalma JA, Cleveland MV, McGowan J, Herrera JL. A randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of polyethylene glycol laxative for chronic treatment of chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 1436-1441.

22. Malcolm A. Is long term laxative use OK for constipated, elderly patients? Modern Medicine of Australia 1999; 42: 97-100.

23. Hsu HJ, Wu MS. Extreme hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemic coma associated with phosphate enema. Intern Med 2008; 47: 643-646.

24. Emmanuel A, Kumar G, Christensen P, et al. Long-term cost-effectiveness of transanal irrigation in patients with neurogenic bowel dysfunction. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0159394.

25. Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, Vandeplassche L. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2344-2354.

26. Piessevaux H, Corazziari E, Rey E, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of long-term treatment with prucalopride. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015; 27: 805-815.

27. Camilleri M, Beyens G, Kerstens R, Robinson P, Vandeplassche L. Safety assessment of prucalopride in elderly patients with constipation: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2009; 21: 1256-e117.

28. Fukudo S, Miwa H, Nakajima A, et al. A randomized controlled and long-term linaclotide study of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation patients in Japan. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018; 30: e13444.

29. Faghihi A, Najafi SS, Hashempur MH, Najafi Kalyani M. The effect of abdominal massage with extra-virgin olive oil on constipation among elderly individuals: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery 2021; 9: 268-277.

30. Faghihi A, Zohalinezhad ME, Najafi Kalyani M. Comparison of the effects of abdominal massage and oral administration of sweet almond oil on constipation and quality of life among elderly individuals: a single-blind clinical trial. BioMed Res Int 2022; 2022: 9661939.

31. Hasanshahi N, Mirzaei T, Ravari A. Comparative study of the effect of acupressure and abdominal massage on constipation in elderly women: a clinical trial study. Gastroenterol Nurs 2022; 45: 159-166.

32. Lafci D, Kasikci M. The effect of aroma massage on constipation in elderly individuals. Exp Gerontol 2022; 171: 112023.

33. Nouhi E, Mansour-Ghanaei R, Hojati SA, Chaboki BG. The effect of abdominal massage on the severity of constipation in elderly patients hospitalized with fractures: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 2022; 47: 100936.

34. Rao SSC, Benninga MA, Bharucha AE, Chiarioni G, Di Lorenzo C, Whitehead WE. ANMS-ESNM position paper and consensus guidelines on biofeedback therapy for anorectal disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015; 27: 594-609.

35. Corsetti M, Brown S, Chiarioni G, et al. Chronic constipation in adults: contemporary perspectives and clinical challenges. 2: Conservative, behavioural, medical and surgical treatment. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021; 33: e14070.