When the going gets tough – a practical approach to refractory constipation

Refractory constipation often results in prolonged discomfort and a diminished quality of life, with more than 50% of patients failing to respond to standard treatments. A personalised treatment approach targeting underlying pathophysiologies can offer improved outcomes for these patients.

- Refractory constipation occurs when patients do not respond to lifestyle modifications or standard therapies for constipation.

- Comprehensive history-taking, physical examination and diagnostic tests are important in identifying the specific phenotype of refractory constipation.

- A personalised treatment approach is essential, targeting the underlying causes, such as dyssynergic defaecation and slow transit constipation.

- Biofeedback therapy is a highly effective treatment for dyssynergic defaecation, with success rates in the order of 70 to 80%.

- Surgical interventions should be reserved for carefully selected patients with isolated slow transit constipation or structural abnormalities.

Constipation can be defined as difficult, unsatisfactory or infrequent defaecation. It is a common complaint, affecting 10 to 15% of the population, and can have a significant impact on quality of life.1 It more commonly affects women than men (2.2:1) and its prevalence increases with age.2 Typical symptoms are listed in Box 1.

Many individuals manage constipation with simple lifestyle changes; however, some experience more persistent symptoms. For a subset of patients, standard treatments fail to provide relief, leading to prolonged discomfort and a diminished quality of life. Refractory constipation refers to constipation that is not responsive to lifestyle modifications, such as increased physical activity or fluid or soluble fibre intake, and that has an inadequate response to osmotic and stimulant laxatives.3 More than 50% of patients fail to respond to these standard treatments.4 This article provides an overview of the causes, diagnosis and management options for refractory constipation, with a focus on a personalised approach to treatment.

Causes of refractory constipation

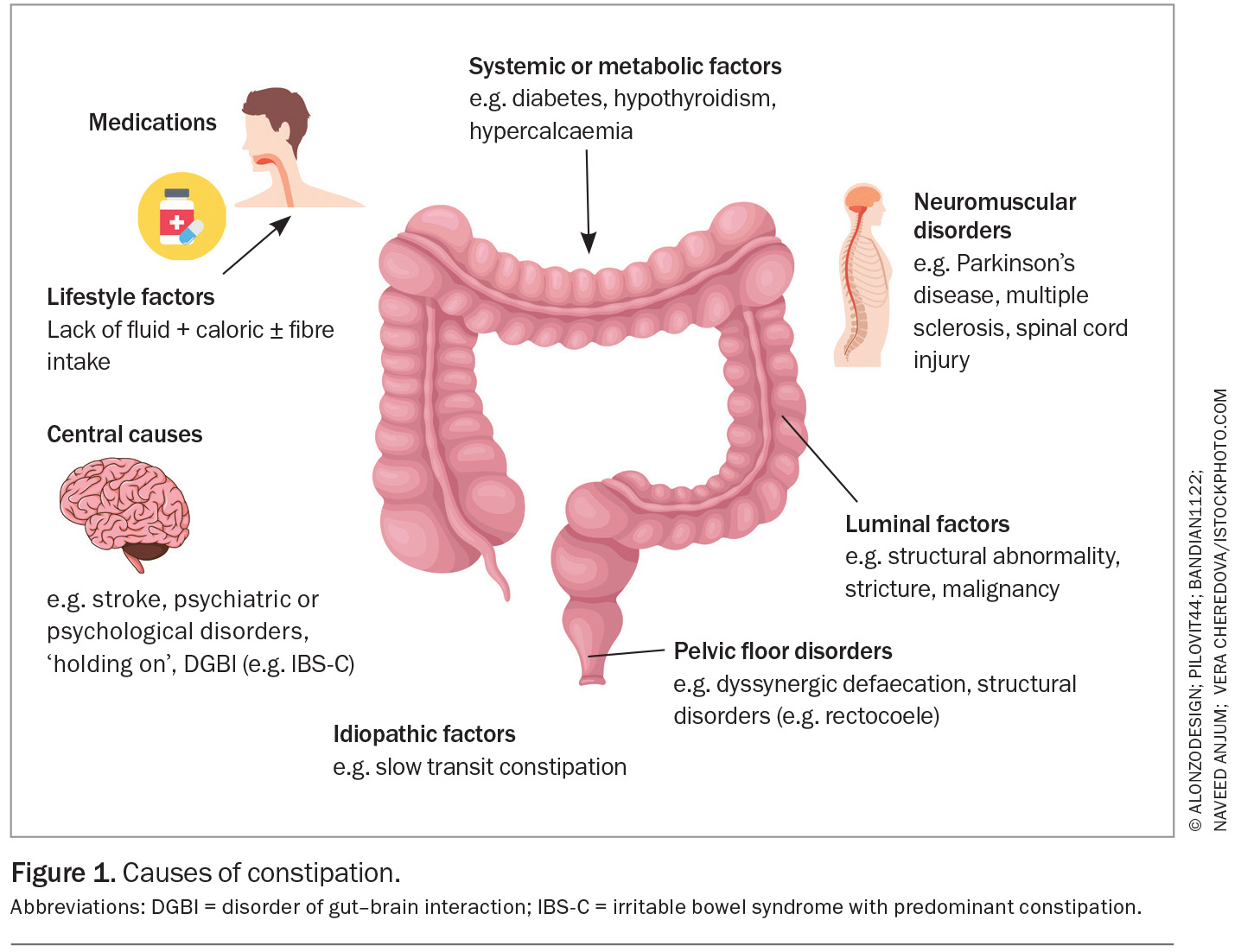

Refractory constipation may be classified by primary and secondary causes, although there are often multiple pathophysiologies (Figure 1). Patients with refractory constipation can be phenotyped according to their underlying pathophysiology, which may allow for a more targeted or personalised approach to treatment.

Primary causes

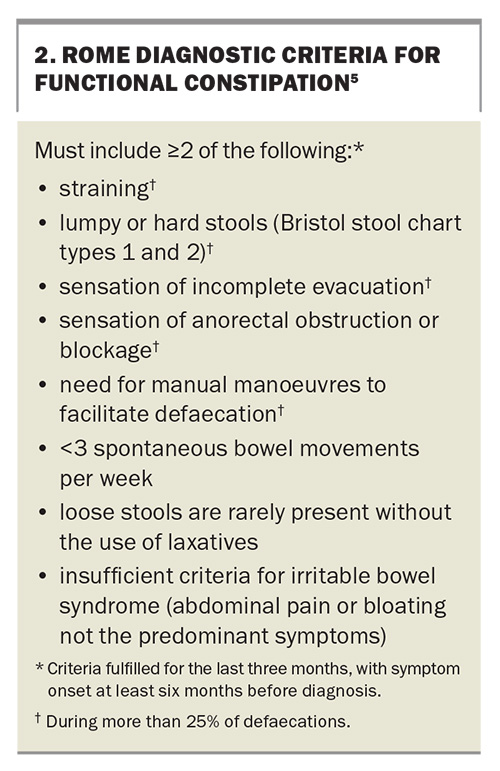

Functional constipation

Functional constipation is a term commonly used to describe constipation without an organic cause and is defined by the Rome IV functional constipation diagnostic criteria (Box 2).5

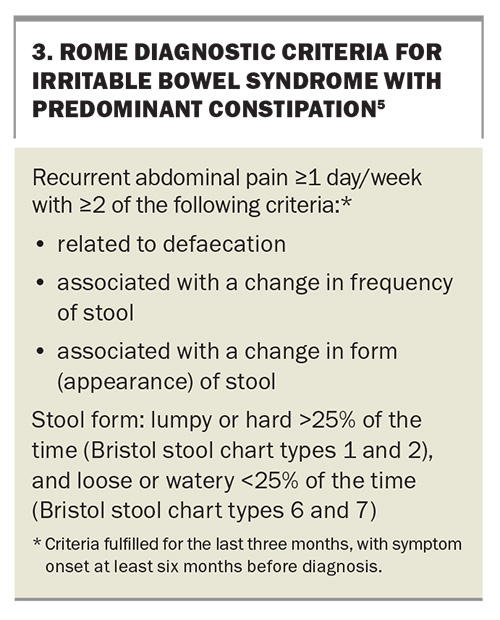

Irritable bowel syndrome-constipation

Abdominal pain is a predominant feature of irritable bowel syndrome with predominant constipation (IBS-C) and is often described by patients as pain that is associated with defaecation. The diagnosis of IBS-C is more likely if other disorders of gut–brain interaction (DGBIs) are present. There is also an association with psychological disorders, such as depression and anxiety.6 IBS-C can be diagnosed using the Rome IV IBS-C diagnostic criteria (Box 3).5

Slow transit constipation

Slow transit constipation is constipation that occurs in association with a delay in transit of content through the colon, which may be diagnosed objectively on validated tests, such as scintigraphy. Slow transit constipation can co-occur with dyssynergic defaecation and may be considered a subset of functional constipation or IBS-C.6

Dyssynergic defaecation

Dyssynergic defaecation (where there is inco-ordination of abdominal and pelvic floor musculature in the defaecation process) represents a significant subgroup of refractory constipation, being identified in 27 to 59% of patients.2 Dyssynergic defaecation reflects an inability to evacuate stool from the rectum because of a physiological or structural pathology of the anorectal and pelvic floor region, often compounded by a behavioural component.7 It is also important to note that although structural disorders such as a rectocoele are common, these do not always directly cause the constipation symptoms, as they can occur in asymptomatic people.

Secondary causes

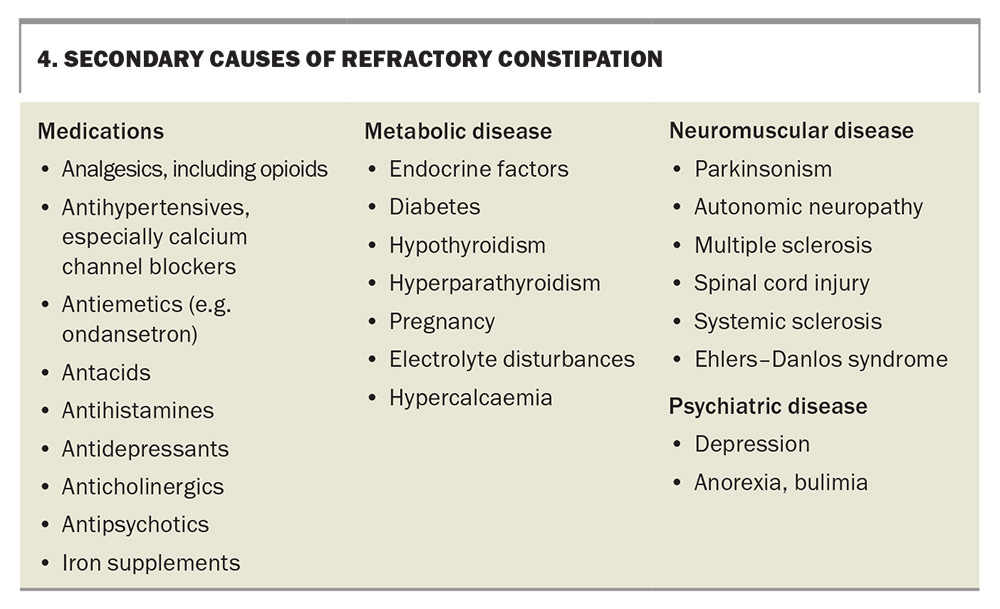

The secondary causes of constipation include medication use, metabolic disease, neuromuscular disease and psychiatric disease (Box 4).

Clinical evaluation of refractory constipation

History

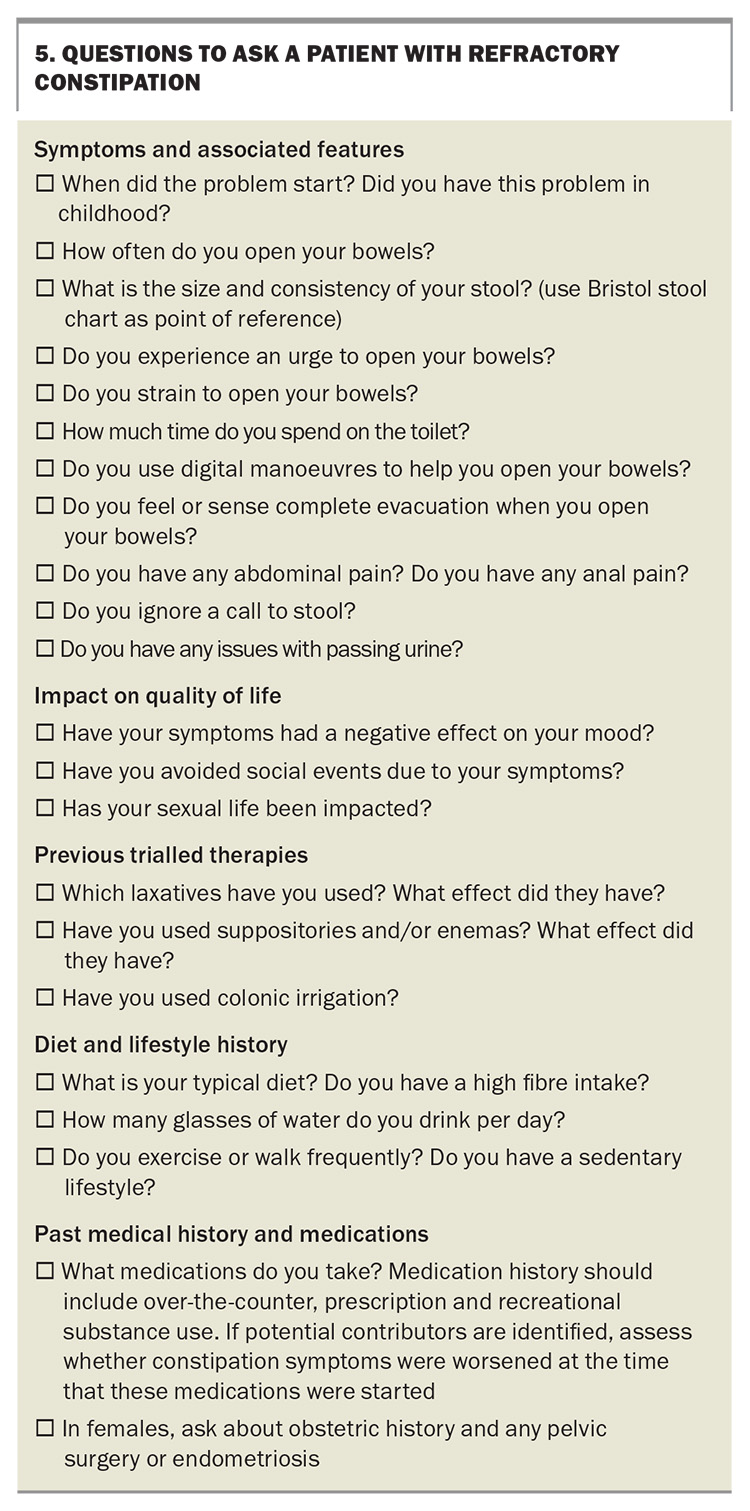

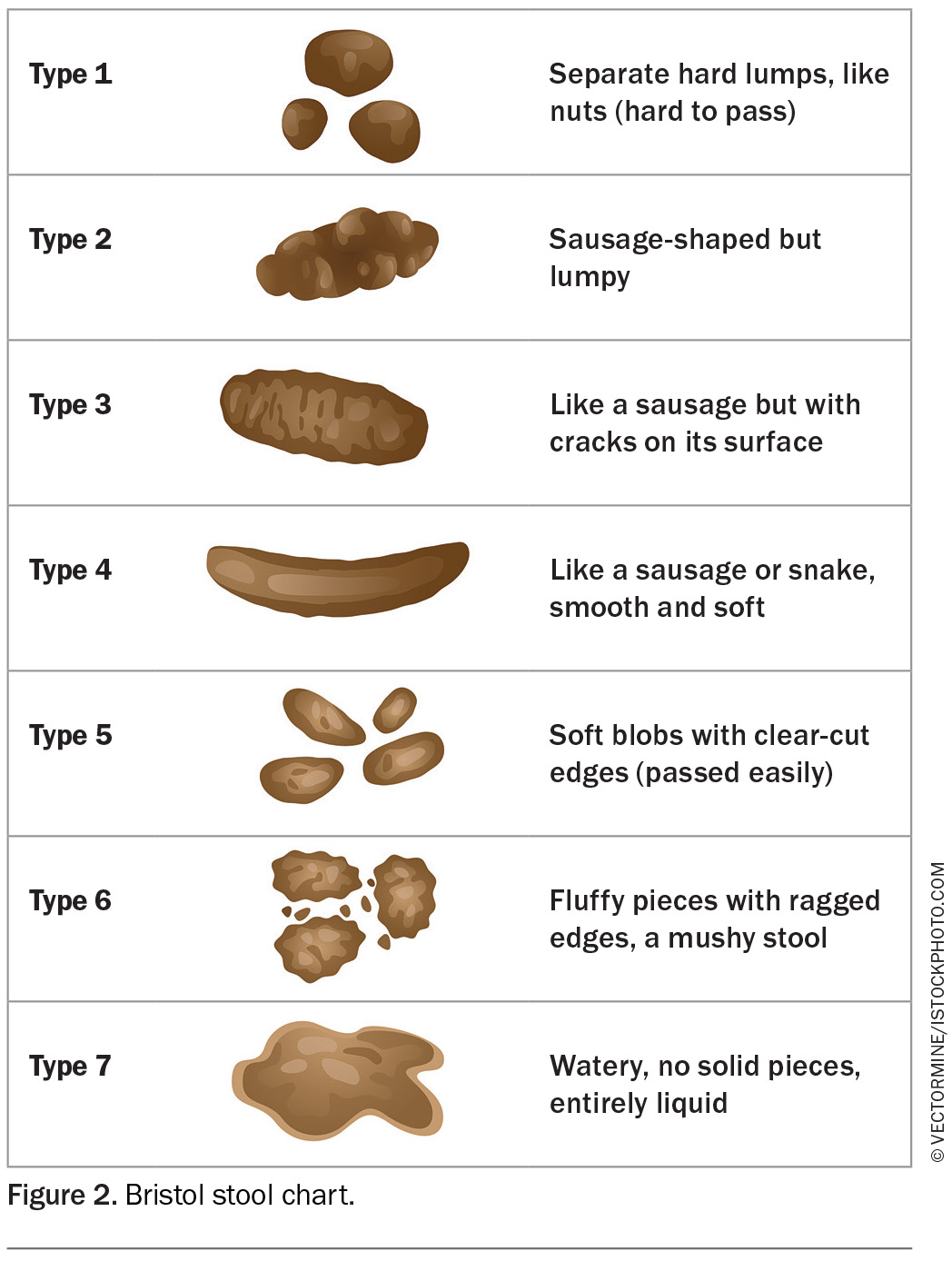

Comprehensive history-taking is crucial in the assessment of refractory constipation. A checklist of questions is presented in Box 5, which may be used as a guide to evaluate a patient with refractory constipation. In addition, asking the patient to maintain a diary, such as a stool, food or symptom diary, may be considered. A stool diary can be a seven-day diary that assesses the number of bowel movements per day, stool consistency (using the Bristol stool chart; Figure 2), level of straining, use of digital manoeuvres, feelings of incomplete evacuation and presence of pain and bloating.8

Examination

Any patients presenting with refractory constipation should undergo a thorough physical examination. This begins with a general inspection and proceeds to a more detailed, systems-specific physical examination looking for signs of secondary constipation. An abdominal examination may reveal abdominal distension and, occasionally, a palpable sigmoid colon loaded with stool. An important yet underutilised part of the physical examination is a careful perianal inspection and performance of a digital rectal examination (DRE). Perianal inspection may reveal external or prolapsing internal haemorrhoids, skin tags, rectal prolapse, anal fissure, anal warts, rashes and excoriations. DREs are helpful in detecting the presence of structural abnormalities, such as a stricture or spasm, tenderness, rectocoele, intussusception, mass or stool. A DRE should be performed to assess three phases:

- rest

- anal squeeze

- bear down.

Patients should be asked to ‘push and bear down’, while the other hand is placed over the abdomen to assess the push effort. In a normal state, the anal sphincter and puborectalis should relax and the perineum should descend. If the muscles paradoxically contract, or if there is no perineal descent, this could suggest underlying dyssynergic defaecation.3 DREs have a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 87% for detecting dyssynergic defaecation.9

Investigations

Initial investigations of refractory constipation should include basic blood tests to exclude secondary causes. Further investigations to define the specific phenotype of refractory constipation may allow for a personalised approach to treatment. These tests are not always necessary but may be appropriate when initial strategies fail.

An abdominal x-ray can be obtained to assess the degree and location of faecal loading. Rarely, CT of the abdomen or pelvis can be considered to exclude gross obstructive pathology, but this is neither specific nor sensitive. However, it may be useful to investigate coexisting symptoms, such as pain. If no obvious pathology is found on initial investigations, then the patient may be referred to a gastroenterology specialist to facilitate additional tests.

Physiological tests

Balloon expulsion test

The balloon expulsion test is a useful screening test to diagnose dyssynergic defaecation. During this test, a compliant balloon is inserted in the rectum and filled with 50 mL of warm water. The patient then attempts to expel the balloon in a toilet or over a commode. A normal expulsion time should be less than one minute. An abnormal expulsion time of longer than one minute suggests dyssynergic defaecation. This test has a high specificity of 80 to 90% but a low sensitivity of 50% in diagnosing dyssynergic defaecation.10

Anorectal manometry, sensory testing and the balloon expulsion test

Anorectal manometry and the balloon expulsion test are used to further diagnose dyssynergic defaecation among individuals with refractory constipation. Anorectal manometry includes assessing the rest and squeeze anal pressures, rectal sensation and simulated defaecation (the balloon expulsion test). During the bear down manoeuvre, the intrarectal pressure increases (≥40 mmHg), simultaneous with a decrease in anal sphincter pressure.11 When there are abnormalities, such as an inability to generate rectal pressure or inability to relax the anal sphincter on bearing down or inability to push out the rectal balloon, a diagnosis of dyssynergic defaecation is made.

In predominantly younger patients with refractory constipation, it can be important to assess the rectoanal inhibitory reflex (anal relaxation upon distension of a rectal balloon), which is absent in Hirschsprung’s disease (a congenital cause of severe constipation). In testing rectal sensation, the patient reports the perception of first sensation, urge to defaecate and the maximum tolerated sensation as a result of distension of a rectal balloon with air.12

Colonic transit test

Tests of colonic transit may be used to diagnose slow transit constipation. In the Sitz marker test, the patient swallows 20 to 24 radio-opaque markers and then undergoes an abdominal x-ray on day 5. Slow transit constipation is diagnosed when more than five (or more than 20%) of the markers are retained on day 5 imaging.3 In scintigraphy, the patient swallows a 111In or 99Tc capsule, which undergoes a pH-sensitive release once in the terminal ileum. Images are acquired at 24 and 48 hours and the percentage of retained activity is reported, giving an indication of colonic transit.13 It is important to note that slow transit can occur as a result of dyssynergic defaecation and may normalise after biofeedback treatment.

Structural tests

Colonoscopy

Direct visualisation of the colon is indicated in selected patients to exclude mucosal lesions, such as solitary rectal ulcer syndrome, inflammation or malignancy. Colonoscopy is only recommended in patients with constipation if red-flag features that could indicate malignancy are present or in those in which colonoscopy is indicated for other reasons e.g. family history.14,15

Defaecography

Defaecography is a test of both structure (e.g. to identify a rectocoele or intussusception) and function (e.g. to assess the degree of rectal emptying). Barium defaecography is performed in a sitting position, over a commode, after installation of 150 mL of barium paste in the rectum. Although this is a cheaper option, this test involves significant ionising radiation exposure. MRI defaecography is performed in a supine position (which is perhaps less physiological) and, although it is more expensive, there is no radiation exposure and it provides excellent detail of all pelvic floor compartments.15

Management

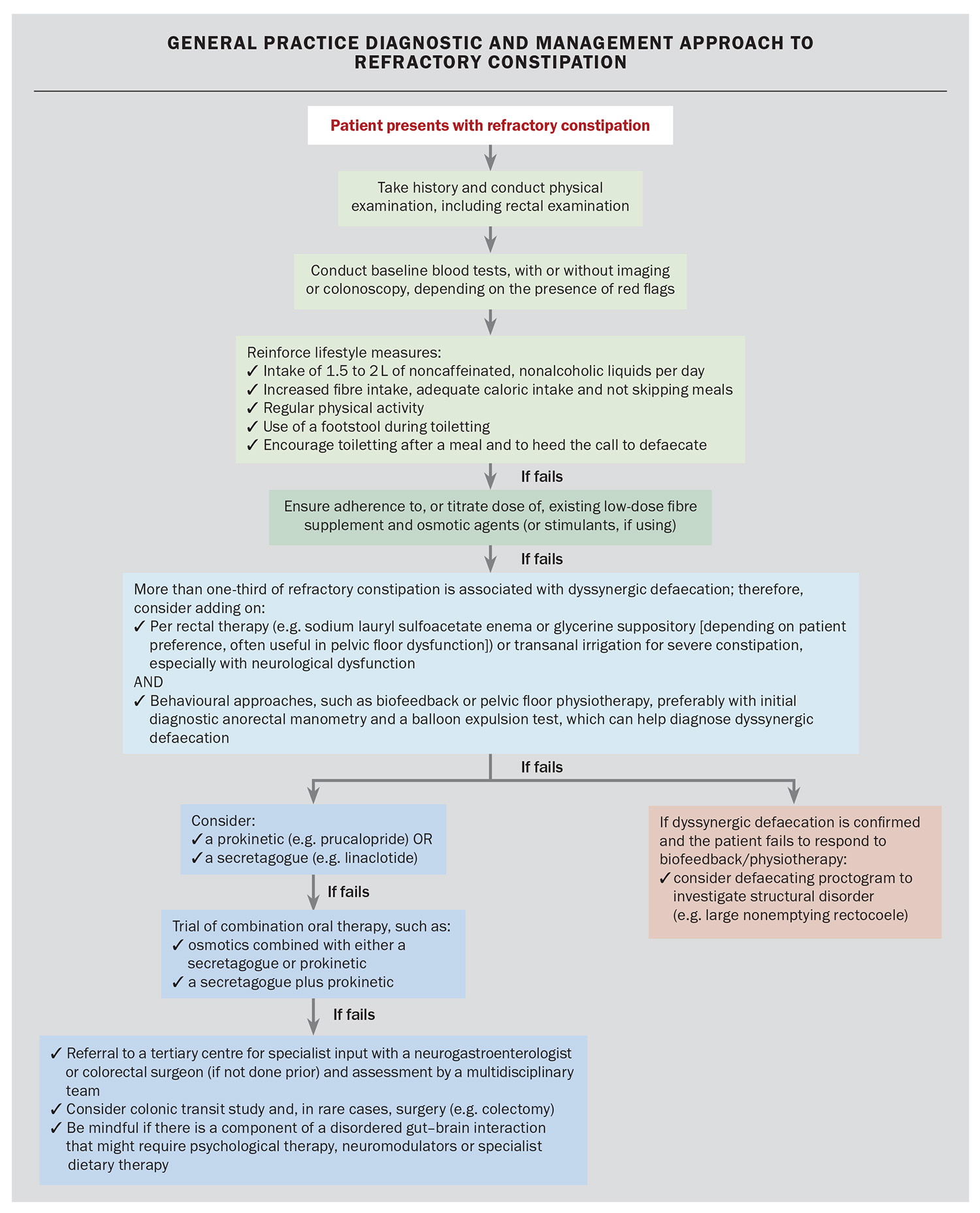

Patients with refractory constipation may need re-enforcement of lifestyle factors in case these have not been strictly adhered to previously. For example, patients should be reminded to maintain oral hydration of 1.5 to 2 L (eight glasses) of water intake daily, maintain soluble fibre intake of 25 to 30 g daily and undergo regular physical activity. Supplemental fibre intake should be advised, especially if dietary fibre intake is inadequate. Patients should be educated on the use of a footstool during toileting, and attempt defaecation after a meal to take advantage of the gastrocolonic reflex.16 Patients with refractory constipation should be maintained on, if necessary, a combination of regular aperients with differing mechanisms of action. For many, as the doses of osmotic agent rise, so does the side effect of bloating; for these patients, adding in (or replacing with) another agent, such as a guanylate cyclase inhibitor (which improves bloating), can be helpful.17 We propose a treatment algorithm for GPs, with possible specialist involvement at the steps indicated, in the Flowchart.

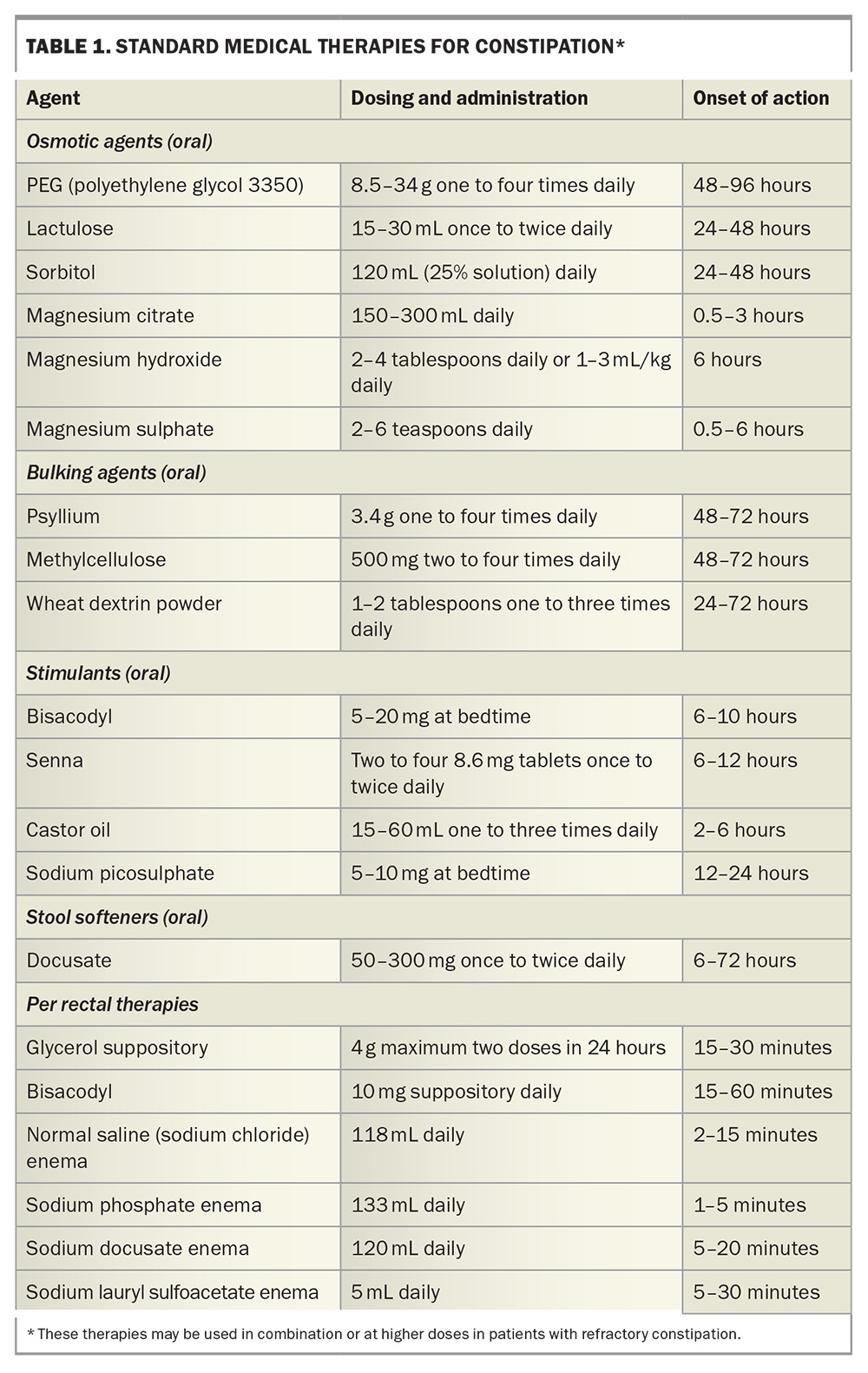

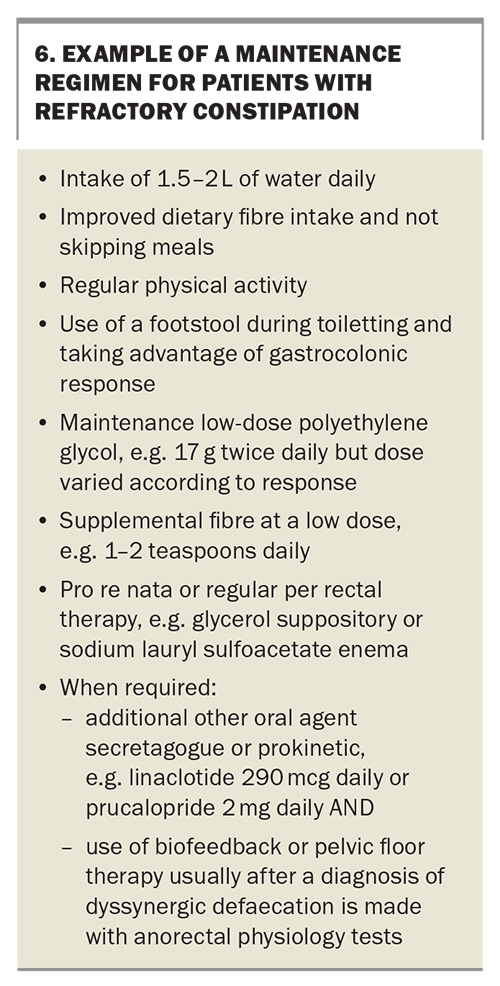

Medications to revise or use in combination in patients with refractory constipation are listed in Table 1. One approach is to start with a low dose and titrate upwards, perhaps preferred in those with coexistent faecal incontinence or those wanting to avoid a sudden increase in bowel movements; however, for some individuals, a higher dose that is then titrated downwards could also be reasonable. A ‘typical’ maintenance regimen for patients with refractory constipation may be as seen in Box 6. High-volume enemas should be avoided in patients at risk of fluid or electrolyte imbalance (e.g. cardiac or renal disease).

When to refer patients to a specialist

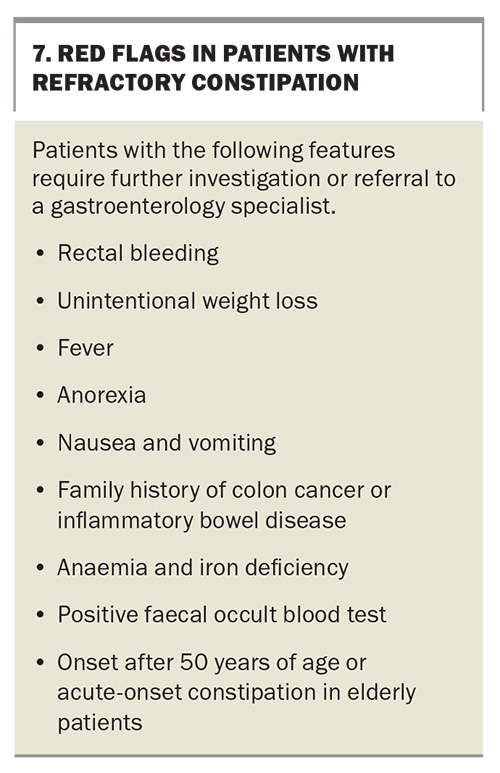

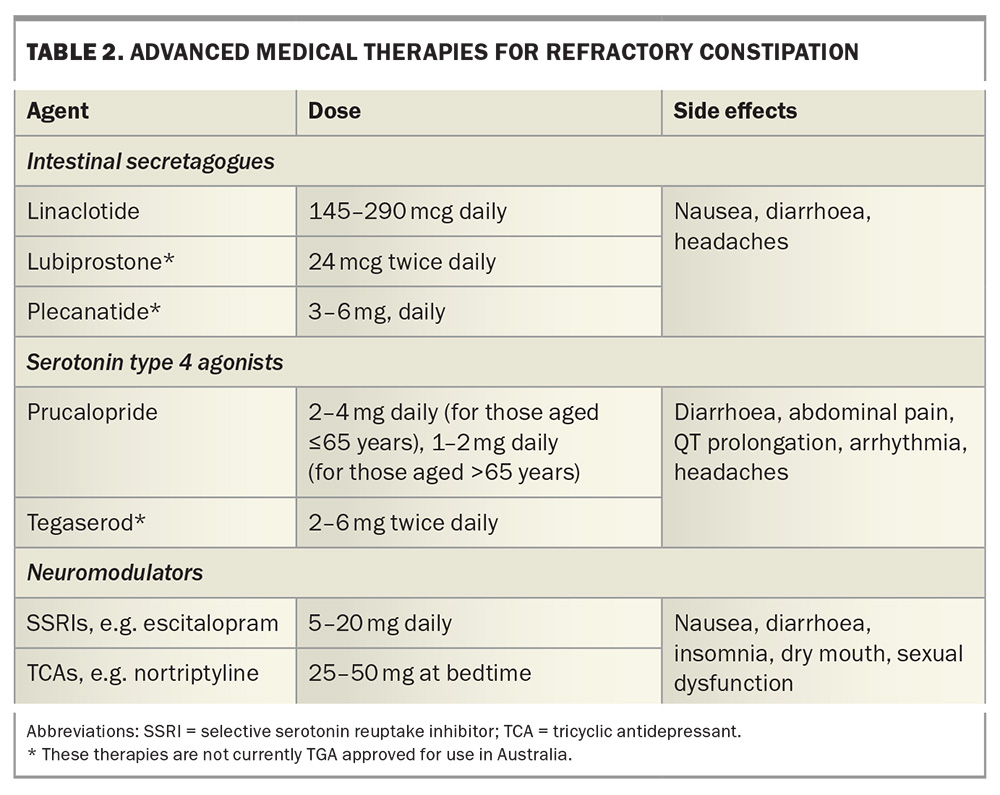

In some cases of refractory constipation, a specialist review by a gastroenterologist is warranted when symptoms persist despite the trial of a maintenance treatment regimen, or if there are any coexisting red flags (Box 7). Additional medications, such as intestinal secretagogues and serotonin type 4 agonists, may be considered (Table 2). In patients with refractory constipation secondary to IBS-C, the addition of neuromodulators for management of abdominal pain may also be considered.18 If a neuromodulator is required, the agent chosen should have the least possible anticholinergic effect.

Anorectal biofeedback therapy and pelvic floor physical therapy

Biofeedback aims to correct dyssynergic defaecation, behaviour and improve rectal sensory perception when these factors are found to be a cause of constipation. Biofeedback sessions use tests, such as manometry or electromyography, to offer patients real-time information about their own physiology in an attempt to normalise defaecation dynamics, and a rectal balloon is used to perform simulated defaecation and rectal sensory retraining.13 On average, four to six sessions of biofeedback are required with a success rate of 50 to 90% in treating refractory constipation.13,19 Although there is high-quality evidence for the efficacy of biofeedback in treating constipation caused by dyssynergic defaecation, specialised biofeedback centres are uncommon.20 Elements of biofeedback are also commonly employed by pelvic floor physical therapists and referral to a physiotherapist specialised in treating constipation is also a reasonable approach.

Psychological therapy

Refractory constipation may be considered part of the spectrum of DGBIs, with many cases of refractory constipation involving IBS-C and often additional concurrent DGBIs. As such, these patients should be treated according to DGBI principles, including the use of neuromodulators and psychological therapies (e.g. gut hypnotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness).21

Surgery

Surgical options for the management of refractory constipation should be employed rarely. In carefully selected patients with confirmed (and usually isolated) slow transit physiology, surgical treatments, such as total colectomy, may offer an improvement in quality of life, with many caveats.22,23 All patients being considered for surgery should be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team experienced in the evaluation and management of constipation.

Surgical options include subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis, colectomy with ileostomy and caecostomy for the administration of antegrade colonic enemas (used more in children).24,25 Uncommonly, those with structural disorders contributing to a defaecatory disorder (such as a large, nonemptying rectocoele or rectal prolapse) should undergo surgery. Those with predominant symptoms of perineal bulge or vaginal prolapse should be referred to a gynaecologist.

Emerging therapies

There are some data for the use of abdominal massage and acupuncture in managing refractory constipation.26,27 In cases of refractory constipation associated with opioid use, peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists may be prescribed, but these are not yet available in Australia.28,29 Transanal irrigation, which uses a device that introduces water up to the splenic flexure, can be used, especially in neurological cases of constipation, but this procedure carries a very small risk of perforation.30 Botulinum toxin injections can be considered in some cases of pelvic floor dysfunction with defaecatory symptoms, although biofeedback is the preferred initial approach.15

A number of other pharmacological treatments are currently undergoing clinical trials. Additionally, novel future therapies being explored include electrical stimulation and ingestion of a vibrating capsule.31,32 There is currently insufficient evidence to support the use of sacral nerve stimulation, herbal preparations, probiotics and faecal microbiota transplants for the treatment of refractory constipation.33-37

Conclusion

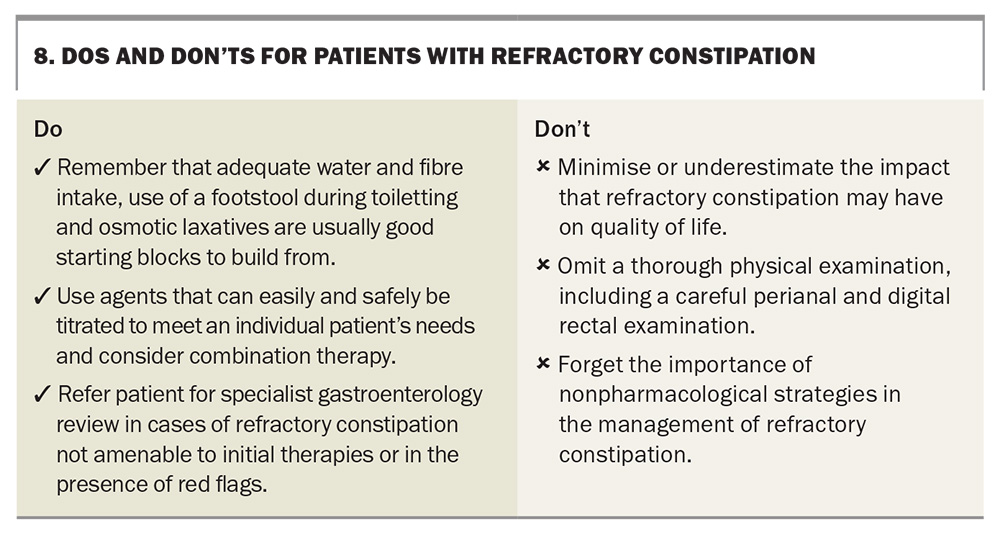

Refractory constipation is common, yet can be challenging to both diagnose and treat, often having a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. Like many aspects of medicine, there is no ‘cookie cutter’ answer to refractory constipation, and these patients may be best served with a personalised approach, often with a combination of treatments targeted at the underlying pathophysiology, if known. Some practice points for GPs are presented in Box 8. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Malcolm has received speaker fees from Sandoz and the European Society of Coloproctology. Dr Nario: None.

References

1. Barberio B, Judge C, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Global prevalence of functional constipation according to the Rome criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 6: 638-648.

2. Suares NC, Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1582-1591.

3. Camilleri M, Brandler J. Refractory constipation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2020; 49: 623-642.

4. Shah ED, Staller K, Nee J, et al. Evaluating the impact of cost on the treatment algorithm for chronic idiopathic constipation: cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2021; 116: 2118-2127.

5. Rome Foundation. Rome IV criteria. Raleigh, NC: Rome Foundation; 2021. Available online at: https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/ (accessed March 2025).

6. Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1393-1407.e5.

7. Rao SSC, Bharucha AE, Chiarioni G, et al. Anorectal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1430-1442.e4.

8. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997; 32: 920-924.

9. Tantiphlachiva K, Rao P, Attaluri A, Rao SSC. Digital rectal examination is a useful tool for identifying patients with dyssynergia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 8: 955-960.

10. Rao SSC, Ozturk R, Laine L. Clinical utility of diagnostic tests for constipation in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 1605-1615.

11. Rao SSC, Singh S. Clinical utility of colonic and anorectal manometry in chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol 2010; 44: 597-609.

12. Vollebregt PF, Burgell RE, Hooper RL, Knowles CH, Scott SM. Clinical impact of rectal hyposensitivity: a cross-sectional study of 2,876 patients with refractory functional constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 116: 758-768.

13. Rao SSC, Meduri K. What is necessary to diagnose constipation? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2011; 25: 127-140.

14. Black CJ, Ford AC. Chronic idiopathic constipation in adults: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and clinical management. Med J Aust 2018; 209: 86-91.

15. Vriesman MH, Koppen IJN, Camilleri M, Di Lorenzo C, Benninga MA. Management of functional constipation in children and adults. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17: 21-39.

16. Hsieh C. Treatment of constipation in older adults. Am Fam Physician 2005; 72: 2277-2284.

17. Rao SSC, Quigley EMM, Shiff SJ, et al. Effect of linaclotide on severe abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 616-623.

18. Staller K. Refractory constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol 2018; 52: 490-501.

19. Kurniawan I, Simadibrata M. Management of chronic constipation in the elderly. Acta Med Indones 2011; 43: 195-205.

20. Serra J, Pohl D, Azpiroz F, et al. European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility guidelines on functional constipation in adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2020; 32: e13762.

21. Kaplan AI, Mazor Y, Prott GM, Sequeira C, Jones MP, Malcolm A. Experiencing multiple concurrent functional gastrointestinal disorders is associated with greater symptom severity and worse quality of life in chronic constipation and defecation disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2023; 35: e14524.

22. Pemberton JH, Rath DM, Ilstrup DM. Evaluation and surgical treatment of severe chronic constipation. Ann Surg 1991; 214: 403-413.

23. Ho YH, Goh HS. The investigation of chronic constipation for surgical management. Singapore Med J 1996; 37: 291-294.

24. Wilkinson-Smith V, Bharucha AE, Emmanuel A, Knowles C, Yiannakou Y, Corsetti M. When all seems lost: management of refractory constipation – surgery, rectal irrigation, percutaneous endoscopic colostomy, and more. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018; 30: e13352.

25. Strijbos D, Keszthelyi D, Masclee AAM, Gilissen LPL. Percutaneous endoscopic colostomy for adults with chronic constipation: retrospective case series of 12 patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017; 30: e13270.

26. Wang X, Yin J. Complementary and alternative therapies for chronic constipation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015; 2015: 396396.

27. Zhang T, Chon TY, Liu B, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for chronic constipation: a systematic review. Am J Chin Med 2013; 41: 717-742.

28. Chey WD, Webster L, Sostek M, Lappalainen J, Barker PN, Tack J. Naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer pain. New Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2387-2396.

29. Mehta N, O’Connell K, Giambrone GP, Baqai A, Diwan S. Efficacy of methylnaltrexone for the treatment of opioid-induced constipation: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Postgrad Med 2016; 128: 282-289.

30. Emmett CD, Close HJ, Yiannakou Y, Mason JM. Trans-anal irrigation therapy to treat adult chronic functional constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 2015; 15: 139.

31. Song G, Trujillo S, Fu Y, Shibi F, Chen J, Fass R. Transcutaneous electrical stimulation for gastrointestinal motility disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2023; 35: e14618.

32. Uwawah TD, Nduma BN, Nkeonye S, Kaur D, Ekhator C. A novel vibrating capsule treatment for constipation: a review of the literature. Cureus 2024; 16: e52943.

33. Patton V, Stewart P, Lubowski DZ, Cook IJ, Dinning PG. Sacral nerve stimulation fails to offer long-term benefit in patients with slow-transit constipation. Dis Colon Rect 2016; 59: 878-885.

34. Chiarioni G, Popa SL, Ismaiel A, et al. Herbal remedies for constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2023; 15: 4216-4216.

35. Ford AC, Quigley EMM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 1547-1561.

36. Tian H, Ge X, Nie Y, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with slow-transit constipation: a randomized, clinical trial. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0171308.

37. Ge X, Zhao W, Ding C, et al. Potential role of fecal microbiota from patients with slow transit constipation in the regulation of gastrointestinal motility. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 441.