A nonhealing ulcer on the hand: a sweet case

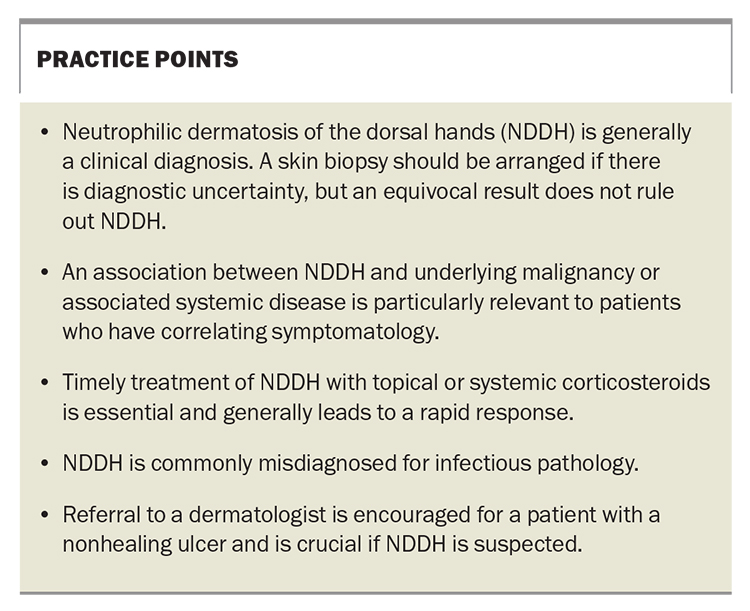

Prompt recognition of neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH) and a search for associated underlying conditions are the keys to appropriate management. Referral to a dermatologist is encouraged for a patient with a nonhealing ulcer and is crucial if NDDH is suspected.

Case scenario

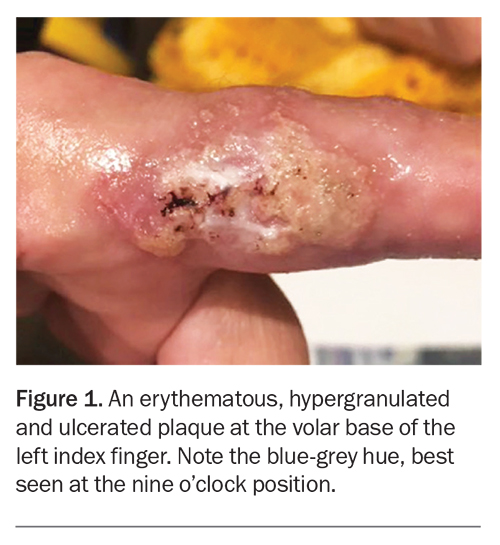

A 59-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a nonhealing nodule on her index finger (Figure 1). She reported a minor laceration to the site two months earlier that had evolved into an ulcerated lesion and gradually expanded.

Clinical examination revealed a tender and ulcerated nodule, 30 mm × 20 mm, on the proximal aspect of the volar left finger. The nodule was erythematous with hypergranulation tissue and a bluish-grey hue. An active erythematous edge was noted. The lesion had been treated with multiple courses of antibiotics, including cefalexin and flucloxacillin, and debridement, but had continued to enlarge.

The patient had a history of hypertension and migraines but was otherwise well. Her regular medications were perindopril and amitriptyline. On questioning, she denied any associated arthralgias, abnormal bowel habit or constitutional symptoms.

Blood tests were arranged, which revealed a mildly elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level; all other results were normal. Wound swabs taken for bacterial and fungal cultures showed no growth, and a PCR test for Mycobacterium ulcerans returned a negative result. A punch biopsy was performed but the histopathological findings were inconclusive, demonstrating features of a benign squamoproliferative lesion and chronic inflammation of the papillary dermis.

A clinical diagnosis of neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hand (NDDH) was made on the basis of the clinical history and the lesion morphology. The patient started treatment with oral prednisolone, initially 25 mg daily to be tapered over four weeks. However, she experienced a mild flare when the dosage was reduced, and consequently the tapering process was resumed at 25 mg daily accompanied by adjunctive topical applications of betamethasone dipropionate twice daily and oral colchicine 500 mcg twice daily. Complete resolution was achieved and the medication regimen was ceased after six weeks. The lesion did not recur.

Discussion

NDDH, formerly known as pustular vasculitis of the hands, is a localised variant of Sweet’s syndrome. It is associated with extracutaneous manifestations of underlying malignancy or systemic inflammatory conditions that contribute to significant morbidity and mortality.1 NDDH is an uncommon condition, with only a few hundred cases described in the medical literature, but it may be more prevalent than generally thought.2 It typically develops in individuals aged in their 60s and has a slight tendency to affect women more than men.3

Clinical presentation

The classic presentation of NDDH is the abrupt onset of erythematous to violaceous lesions – papules, plaques, nodules, pustules or haemorrhagic bullae – on the dorsum of the hand. The lesions are exquisitely tender but not pruritic. There may be secondary features of ulceration.2 Involvement is less likely for the finger and wrist and especially rare for the palmar surface.2 A history of physical trauma to the affected hand is common.2 Occasionally, systemic symptoms, including fever, malaise and arthralgias, may accompany the cutaneous findings. NDDH is often idiopathic and, rarely, may be drug-induced by thalidomide and its analogue lenalidomide.2

NDDH has been associated with an underlying haematological disorder, particularly myelodysplasia and leukaemia, in about half of affected patients.4 Other recognised comorbid conditions include inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis.4 An association between NDDH and underlying malignancy or associated systemic disease is particularly relevant to patients who have correlating symptomatology. Therefore, a comprehensive history and physical examination are important to determine whether a coexisting condition is contributing to a presentation of NDDH. If NDDH is suspected, dermatological review is crucial to aid in diagnosis and initiation of correct treatment.

Pathophysiology

The presence of a neutrophilic infiltrate of the skin that is independent of infection is characteristic of neutrophilic dermatoses, including NDDH. However, the pathophysiology of these conditions is poorly understood. The role of trauma as a trigger may reflect the process of cutaneous pathergy, an exaggerated response to skin injuries such as insect bites or biopsies that may induce lesions at these sites.5 Dysregulation of several inflammatory cytokines is an emerging concept that implies a multifactorial aspect of the disease.6

Differential diagnoses

NDDH is often misdiagnosed as an infectious process. The condition may also mimic surgical pathology such as necrotising fasciitis, which can lead to inappropriate treatment (such as surgical debridement) and significantly worsen the condition.1

It is important to consider other neutrophilic dermatoses as differential diagnoses, which include pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema elevatum diutinum.7 The morphology and progression of the lesions, along with the histopathology results, can help in distinguishing between these conditions.

Investigations

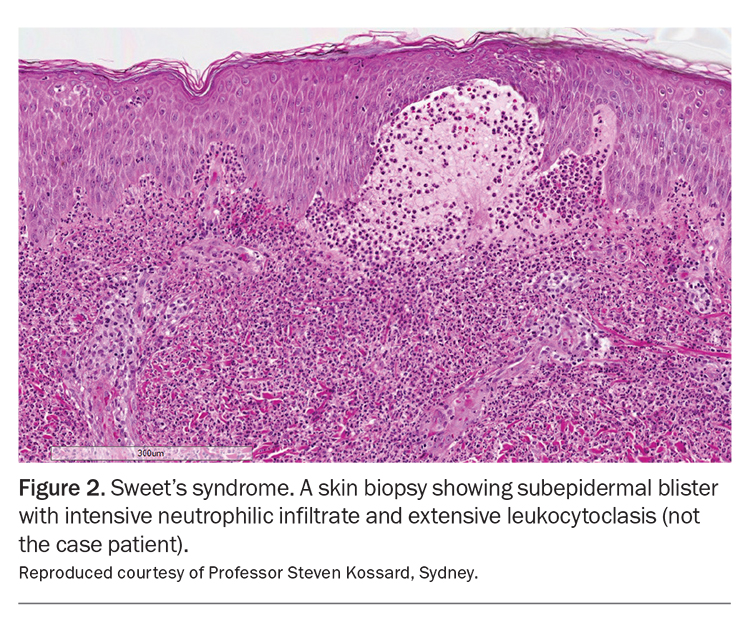

NDDH is usually a clinical diagnosis; however, if there is diagnostic uncertainty then a skin biopsy is advisable. Hallmark histopathological features include a dense infiltrate of predominantly neutrophils with leukocytoclasis within the dermis and papillary dermal oedema (Figure 2).8 There may also be a lack of evidence of true leukocytoclastic vasculitis such as the absence of fibrin deposition or neutrophils within the vessel walls.8 However, an equivocal biopsy result, including the lack of a dense neutrophilic infiltrate, does not rule out NDDH. Atypical histological features may be explained by temporal progression of the disease, as delayed biopsy specimens may demonstrate a more chronic mixed inflammatory picture.9 Prior treatment with corticosteroids will reduce the neutrophilic infiltrate within a specimen. In addition, a tissue sample that provides only a limited view of the papillary dermis, where neutrophils can be difficult to visualise, may be inadequate for demonstrating the features of NDDH. As skin infections may closely mimic NDDH, tissue samples taken for biopsy should also be sent for bacterial, fungal and mycobacterial cultures to exclude an infectious cause.10

Additional investigations should be guided by reasonable clinical suspicion for underlying systemic disorders.10 Screening for underlying malignancy should be age-appropriate and may in the first instance include an up-to-date faecal occult blood test, cervical screening test and mammogram.10

Management

The treatment of NDDH is underpinned by topical and systemic corticosteroids. A rapid improvement in skin lesions and symptoms (within a few days) is often seen after starting a combination therapy of ultrapotent topical corticosteroids and systemic prednisolone.4 To prevent relapse or recurrence, a gentle taper of oral corticosteroids over several weeks has been suggested (e.g. an initial dose of 25 mg of prednisolone daily, then decreased by 2.5 to 5 mg every five days until discontinuation).4 If NDDH is refractory to corticosteroids, dapsone or colchicine (off-label uses) may be trialled for their antineutrophilic activity.4 Corticosteroid-sparing agents such as methotrexate or mycophenolate may be useful, after consideration of the patient’s comorbidities and contraindications.4

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with NDDH tends to be good, with a rapid resolution of cutaneous and systemic symptoms without scarring. However, recurrent episodes are likely in those who have an underlying malignancy.4

Conclusion

GPs may be the first healthcare providers to encounter people with NDDH in the community. Prompt recognition of the condition and a search for associated underlying diseases are the keys to expediting appropriate management. NDDH is a highly treatable condition, but delay in treatment and inappropriate surgical intervention can lead to substantial morbidity and impaired quality of life. A collaborative approach to care is advocated for patients who have NDDH, with dermatologist involvement to ensure confirmation of the diagnosis and oversee the monitoring of relapse and recurrence, as well as involvement of other specialists, as required, for the diagnosis and management of underlying or associated comorbidities. Practice points are listed in the Box. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None

References

1. Sanchez IM, Lowenstein S, Johnson KA, et al. Clinical features of neutrophilic dermatosis variants resembling necrotizing fasciitis. JAMA Dermatol 2019; 15: 79-84.

2. Mobini N, Sadrolashrafi K, Michaels S. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: report of a case and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med 2019; 2019: 8301585.

3. Micallef D, Bonnici M, Pisani D, Boffa MJ. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: a review of 123 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; S0190-9622(19)32678-7.

4. Oakley A. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands. DermNet: New Zealand Dermatological Society; 2015. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/neutrophilic-dermatosis-of-the-hands (accessed May 2023).

5. Cheng AMY, Cheng HS, Smith BJ, Stewart DA. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: a review of 17 cases. J Hand Surg 2018; 43: 185.e1-185.e5.

6. Marzano AV, Ortega-Loayza AG, Heath M, et al. Mechanisms of inflammation in neutrophil-mediated skin diseases. Front Immunol 2019; 10: 1059.

7. Del Pozo J, Sacristan F, Martinez W, Paradela S, Fernández-Jorge B, Fonseca E. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the hands: presentation of eight cases and review of the literature. J Dermatol 2007; 34: 243-247.

8. Cohen PR, Honigsmann H, Kurzrock R. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet syndrome). In: Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in general medicine, 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999. pp. 289-295.

9. Weenig RH, Davis MDP, Dahl PR, Su WPD. Skin ulcers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1412-1418.

10. Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome and cancer. Clin Dermatol 1993; 11: 149-157.