Genetic carrier screening in pregnancy: informing patients

This series highlights common medicolegal issues in general practice. Written by a team from medical defence organisation Avant, the series is based on actual situations, with details changed for privacy and some issues summarised for the sake of discussion. This scenario considers questions raised, particularly for obstetric and shared-care GPs, when informing pregnant patients about genetic carrier screening.

Genetic carrier screening and testing may not yet be routine for all patients and couples planning or in the early stages of a pregnancy. However, that time may not be far off. Current guidelines recommend all women planning a pregnancy or in the first trimester of pregnancy should be offered information about carrier screening for genetic conditions.1-3

This recommendation is in addition to the recommendation to check for a family history of genetic disorders and to refer couples with a family history of any genetic disorder for counselling before screening.1 The rationale is that most children affected by recessive conditions are born to parents with no known family history of the condition.2 It is also in addition to recommendations on prenatal screening for fetal chromosome or genetic conditions, such as trisomies 21, 18 and 13, and fetal structural conditions, such as neural tube defects.4,5

From late 2023, it is expected that genetic carrier screening for three common genetic conditions (cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome) will be available through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) for all couples planning or in the early stages of a pregnancy.6,7 Expanded genetic carrier screening, potentially covering hundreds of conditions that vary between providers, is also available but is not covered by Medicare.

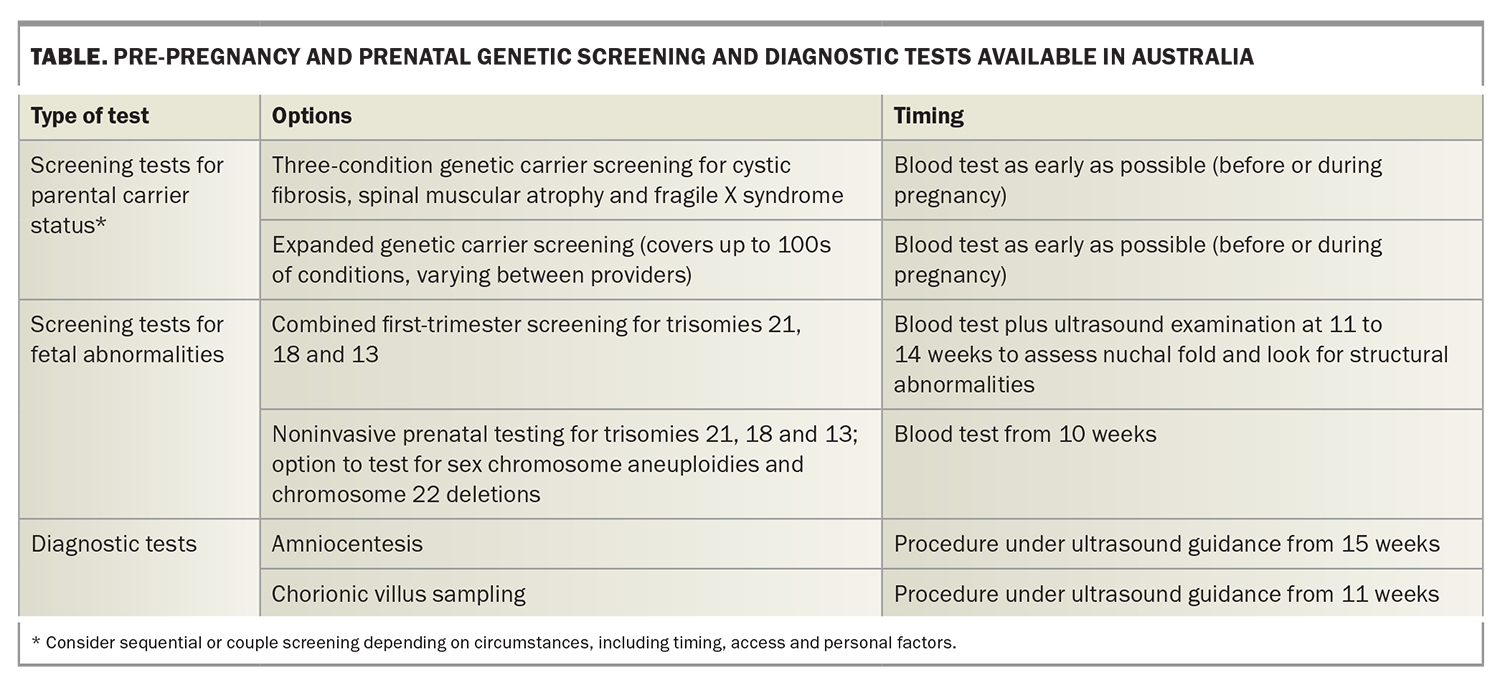

As with any new treatment, as genetic carrier screening becomes more widely available and expected, there are practical and medicolegal issues to consider. The following scenario and discussion focus on an emerging challenge for doctors: helping patients understand the potential implications of genetic carrier screening and testing in pregnancy so they can make an informed decision. Prenatal screening and testing options available in Australia are shown in the Table.

Case scenario

Presentation

Anna is a new patient to the general practice who asks to see Dr M, an obstetric GP, as she thinks she is pregnant. She is in her 30s and tells Dr M this is her first pregnancy and was not planned.

Anna and her partner have been moving around to find work after both losing their jobs in the past year. She has found a casual job and her partner is working interstate on a remote mine site. Although her partner is supportive, she says she is feeling anxious about the pregnancy with her partner away so often. She has seen news reports about genetic carrier screening and wants to know what tests she can have now that the government is making funding available.

Dr M is aware of the guidelines recommending genetic carrier screening but is concerned about how to ensure Anna and her partner, who is not present at the consultation, understand the options and implications.

Medicolegal issues: autonomy and informed decision-making

Medicolegally, informing patients and their partners about genetic carrier screening and testing in pregnancy seeks to maximise patient autonomy and allow patients and their partners to make informed decisions. The consent process for genetic carrier screening may be regarded as the same as for any procedure or treatment. Through discussion between the doctor and patient, the patient will be provided with enough information that they can weigh up the risks material to them, understand the likely costs and come to an informed decision.

The concept of informed consent is closely aligned to the ethical principle of autonomy. Patients should be empowered to make a ‘voluntary decision with knowledge and understanding of the benefits and risks involved’.8

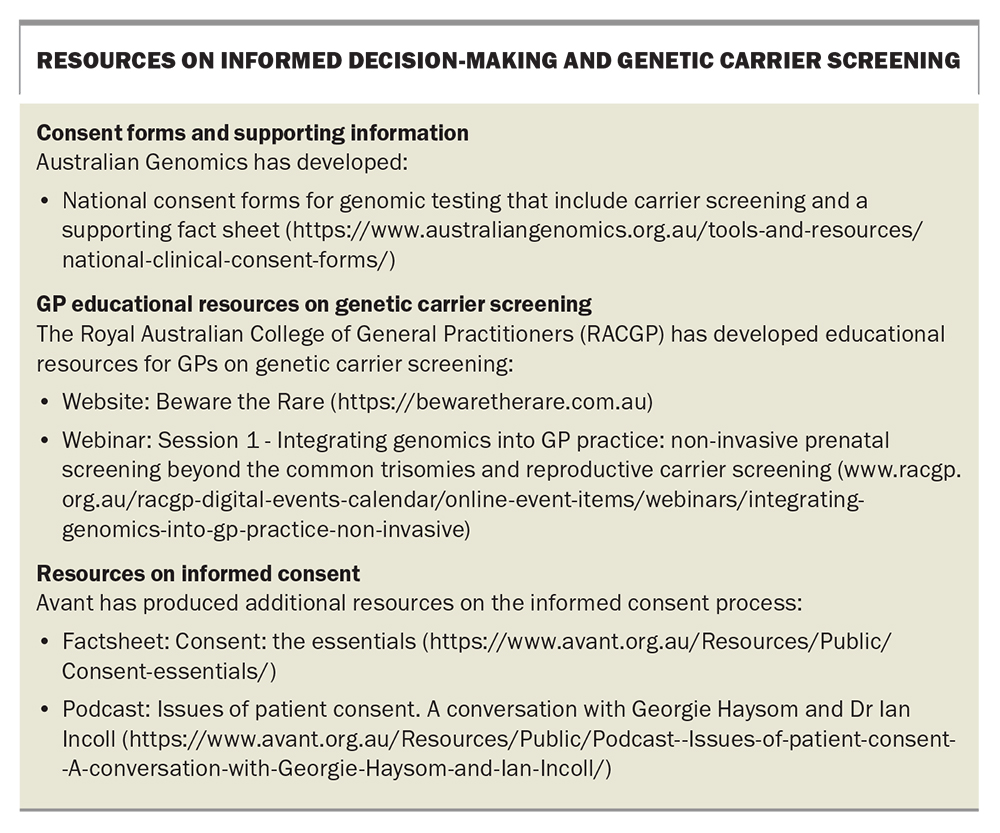

Although doctors are not expected to discuss every conceivable risk, you do need to disclose general risks, known complications and common side effects. You also need to explore the patient’s concerns and make sure you discuss risks that are material to the patient personally. Resources on informed decision-making in the context of genetic carrier screening are shown in the Box.

As doctors will be aware, ensuring patients receive the information they need and understand the implications of any treatment can be challenging. Any new or innovative treatment is likely to involve an additional layer of complexity. Genetic carrier screening and testing present further issues to keep in mind, particularly because:

- screening is not diagnosis, and the risk of a disease or disorder arising from genetic variation is often uncertain and can be difficult to understand9

- the increasing choice and availability of tests can make it difficult to be clear what is being tested for and the relative merits of the different tests available

- the ability to detect genetic variations is evolving rapidly, but results can still be uncertain

- genetic information may have implications for individuals other than the patient, including other family members.

Discussion

Supporting informed decision-making

The recommendation that information about genetic carrier screening be offered to all women planning or in early pregnancy applies in addition to genetic counselling and specific testing based on family history, ethnicity or population risk.1,2 Genetic carrier screening can detect whether an individual is a carrier for single-gene disorders such as cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome, conditions that cannot be detected by noninvasive prenatal testing. Preconception genetic carrier screening can give couples information on which to base reproductive choices. Genetic carrier screening during pregnancy can identify an increased likelihood of a condition, which may help inform decisions about more invasive diagnostic testing.3

Explaining genetic carrier screening can be challenging, even for those with a family history or awareness of factors that increase the chances of inheriting a condition. For patients such as Anna, with no such history, it is particularly important to help her understand:

- what screening might reveal about the chances of her child being affected by a genetic condition

- issues that genetic carrier screening may not identify and additional tests that may still be necessary (including noninvasive prenatal testing and combined first-trimester screening)

- her options based on her carrier status, including diagnostic testing, such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling (CVS).

This does not mean all doctors are expected to offer genetic counselling. However, courts have found that it is not enough simply to tell a patient that genetic counselling or screening options are available. Obstetricians and obstetric and shared-care GPs are expected to keep up with professional development in this area and be aware of changes so they can advise patients. If you advise patients on genetic carrier screening, you need to give them enough information about the reasons for seeking counselling or screening so that they can make an informed decision about whether to pursue it.10 If you do not offer obstetric or antenatal care as part of your practice, be aware of the guidelines so that you can refer pregnant patients appropriately as a matter of priority to ensure screening can be addressed early in the pregnancy.

Helping patients understand probabilities and uncertainty

It is expected that most patients who are pregnant or planning pregnancy will opt for three-condition screening for cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome. Screening for these common genetic conditions is expected to be covered by Medicare from late 2023, after an announcement in the March 2022-23 budget of $81.2 million funding over four years.6,7 Expanded genetic carrier screening is also now available, which may offer the potential to test for genetic variations associated with hundreds of conditions, although this is not currently supported by Medicare and may involve patient costs of up to $900.

Particularly in the context of broader screening and rarer conditions, there has been increased concern about how

to manage genetic variations of uncertain clinical significance.9,11 The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) guidelines on genetic carrier screening recommend that laboratories do not report variants of uncertain significance in carrier screening.1 However, this does not mean that genetic test results are always clear or definitive.

Patients often struggle with the fact that, even after screening and testing, they may still need to make decisions based on incomplete information. Anna appears to want as much information as possible, but she may have unrealistic expectations about what screening will tell her. It is not clear what her partner’s view or understanding is, and Dr M will need to consider and discuss with Anna how to engage him in the discussion. Anna may not understand that, if she or her partner are found to be carriers, further diagnostic testing, such as amniocentesis and CVS (with their associated risks), may be necessary. Even these may not give her certainty about:

- the presence of a genetic mutation

- whether inheriting the mutation means her child will go on to develop a genetic condition

- how a condition might be expressed or how it might affect her child’s health.

Providing test results

There is an increasing emphasis on consistency in reporting standards for Australian accredited pathology laboratories.12 However, the expanding variety of genetic tests available in Australia and overseas, and the different ways in which results are reported, have made it challenging for doctors to explain genetic test results so that patients have the information they need.

Previous research by Avant has identified concerns from both geneticists and other healthcare professionals about the difficulty of interpreting and explaining test results.13 Results and reports are not always consistent, and the significance of variants is not always clear. Consequently, a ‘negative’ result could mean that a particular variant was not tested or that the significance of a particular variant is not yet understood.

There have been cases where patients undergoing screening have been given incorrect information about their chances of developing or passing on a genetic disorder because practitioners were unfamiliar with the test or reporting format.14

This makes it particularly important that Dr M is clear in her own mind, and can explain to Anna, what variations have been tested for, and what the tests showed. If Dr M is not clear or is uncertain about the information she should provide, she should refer Anna and her partner for specialist advice.

Engaging and screening partners

Both parents may ultimately need to be screened for genetic carrier status. However, in the absence of any family history, sequential screening may be a more cost-effective option when testing for X-linked or autosomal recessive conditions. The pregnant woman could be screened first, and her partner screened for the recessive conditions if she is found to be a carrier. Nevertheless, time constraints and other factors specific to the couple’s situation may mean it is appropriate for both partners to consider carrier screening at an early stage.2

Allowing time to consider options

For couples who are planning a pregnancy, there is the option to take more time to discuss genetic carrier screening. For patients such as Anna, who ask about screening when confirming a pregnancy, there are additional time pressures. Anna needs to understand she will have limited time for further decisions if necessary, for example about whether to undergo further diagnostic testing or to continue the pregnancy. She may require multiple consultations to process available information and reach a decision.

Although doctors will already be managing time pressures in the context of routine antenatal testing, the additional time for screening tests for one or both partners, receiving test results and potential genetic counselling, all mean that genetic carrier screening should start as soon as possible. If genetic counselling is required during pregnancy, genetics units often recommend doctors phone for an urgent referral to ensure patients are triaged appropriately.

Presenting information neutrally and avoiding assumptions

Choices about whether to seek screening, further testing and what to do in the event of a positive test result are all highly personal. However, research consistently indicates that the way in which doctors present information to patients can have a significant influence on their decisions. When screening is recommended by a doctor or presented as a usual part of responsible care, patients may feel reluctant to decline it.9,15

Given that Anna has indicated she is anxious about the pregnancy as her partner is away so often, and that she has asked about the tests she can have, it is reasonable for Dr M to infer that Anna will want as much information as possible. Nevertheless, it is important that Dr M presents information as neutrally as possible and does not make any assumptions about the choices Anna may make.

The term ‘risk’ is often used in the context of informed consent to treatments or conditions; however, guidelines on prenatal screening or diagnostic testing prefer the terms ‘probability’ or ‘chance’. This follows a complaint to the Tasmanian Anti-Discrimination Commissioner from the parent of a child with Down syndrome who argued that the negative connotations attached to the concept of risk could add to the stigma attached to a diagnosis and influence women’s decisions about whether to proceed with a pregnancy.16

Although information can help parents plan for a child with a potential disability, others may choose not to know. Parents have expressed concerns, for example, about treating children as ‘patients in waiting’, even if they have mild or no symptoms of the condition.11 Patients may complain about healthcare providers who assume they would wish to terminate a pregnancy based on test results, or who feel they are judged for wishing to continue a pregnancy.17

Informed financial consent

Although the issue of financial consent is not unique to genetic carrier screening, it is important to ensure patients understand the costs involved. Anna seems to assume that screening is covered under Medicare. However, until changes to the Medicare Benefits Schedule are implemented, she is unlikely to be able to access Medicare rebates for genetic carrier screening. As costs can range from $350 to $400 for three-condition screening, up to $900 for expanded genetic carrier screening, it may be a significant factor in Anna’s decision.2 Dr M needs to make sure she understands there may be additional costs and where to get more information about costs involved.

Outcome

Anna believes her conception date was about a month ago. Dr M takes Anna’s clinical and family history and organises prenatal blood tests and a dating ultrasound scan. She also talks to Anna about the option of having three-condition genetic carrier screening and explains the costs.

Dr M is aware the laboratory she usually uses is currently taking about seven to 10 days to return screening results so she suggests that, while Anna’s partner is away and unable to access testing, Anna could have her test first. If tests indicate she is not a carrier, there is a very low chance that her baby would be affected with those conditions.

Dr M provides Anna with information and resources on genetic carrier screening.2 She explains that if testing does indicate Anna is a carrier, she would arrange testing for her partner and refer her for genetic counselling to give her more information and help her understand her options. She also explains that there are other screening and diagnostic tests available, including combined first trimester screening and noninvasive prenatal testing, which can give her more information about the chances of her child being affected by a genetic or chromosomal disorder.

Dr M and Anna schedule a further consultation for after the genetic carrier screening test results are back, and when her partner will be available, so that they can discuss additional screening options in more detail.

Dr M makes a detailed note of her discussion with Anna, the plan for follow up and resources she has provided her.

Conclusion

First-trimester screening for fetal chromosome abnormalities is currently well established in prenatal care via blood test and ultrasound examination. In addition, pregnant women have the option of privately funded noninvasive prenatal testing that more accurately defines the risks and can also identify fetal sex chromosome aneuploidies and chromosome deletions. High-risk results need confirmation with diagnostic testing.

More recently, genetic carrier screening has become widely available in Australia at a cost to patients. This is an evolving area and expanded testing panels are increasingly available. Couples with a family history of any genetic condition should be referred for genetic counselling before screening and preferably before conception. From November 2023, genetic carrier screening for cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome is expected be Medicare-funded and available to all couples. Most babies born with these conditions have no known family history. Obstetric and shared-care GPs should be aware to offer this option to women and their partners before conception or early in pregnancy and be familiar with how to counsel patients accordingly. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None

References

1. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). Genetic carrier screening. Guideline C-Obs 63. Melbourne: RANZCOG; 2019. Available online at: https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Genetic-carrier-screeningC-Obs-63New-March-2019_1.pdf (accessed February 2023).

2. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Genetic carrier screening. A guide to preconception and earlier pregnancy carrier screening for hereditary rare diseases. Melbourne: RACGP; 2020. Available online at: https://bewaretherare.com.au/wp-content/themes/bewaretherare/pdfs/Genetic-carrier-screening.pdf (accessed February 2023)

3. Baume D, Ganu P. Genetic carrier screening: an update for GPs. Med Today 2022; 23(3): 49-56.

4. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). Prenatal screening and diagnostic testing for fetal chromosomal and genetic conditions. Guideline C-Obs 59. Melbourne: RANZCOG; 2019. Available online at: https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Prenatal-Screening-and-Diagnostic-Testing-for-Fetal-Chromosomal-and-Genetic-Conditions.pdf (accessed February 2023).-

5. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). Prenatal screening for fetal genetic or structural conditions. Guideline C-Obs 35. Melbourne: RANZCOG; 2019. Available online at: https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Prenatal-Screening-for-Fetal-Genetic-or-Structural-Condition.pdf (accessed February 2023).

6. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Genomics in general practice. Genetic tests and technologies. Reproductive carrier screening. Melbourne: RACGP; 2023. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/genomics-in-general-practice/genetic-tests-and-technologies/reproductive-carrier-screening (accessed February 2023).

7. Australian Government. Budget 2022-23. Budget Measures: Budget Paper No 2. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2022. Available online at: https://archive.budget.gov.au/2022-23/bp2/download/bp2_2022-23.pdf (accessed February 2023).

8. Medical Board of Australia. Good medical

practice: a code of conduct for doctors in Australia. Melbourne: Medical Board of Australia, 2020. Available online at: https://www.medicalboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Policies/Code-of-conduct.aspx (accessed February 2023).

9. Thomas J, Harraway J, Kirchhoffer D. Non-invasive prenatal testing: clinical utility and ethical concerns about recent advances. Med J Aust 2021; 214: 168-170.e1.

10. Waller v James [2015] NSWCA 232.

11. Johnson F, Ulph F, MacLeod R, Southern KW. Receiving results of uncertain clinical relevance from population genetic screening: systematic review & meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2022; 30: 520-531.

12. National Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council. Requirements for human medical genome testing utilising massively parallel sequencing technologies. Canberra: the Council; 2017. Available online at: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/npaac-pub-mps (accessed February 2023).

13. Avant. Genomic testing and medico-legal risk: a discussion paper. Sydney: Avant; 2020. Available online at: https://www.avant.org.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=23622330094 (accessed February 2023).

14. Eastbury v Genea Genetics [2015] NSWSC 1834.

15. McClaren BJ, Delatycki MB, Collins V, et al. ‘It is not in my world’: an exploration of attitudes and influences associated with cystic fibrosis carrier screening. Eur J Hum Gen 2008; 16: 435-444.

16. Gibson S. Down syndrome testing results delivery to change nationally following Tasmanian complaint. ABC News 2016; October 9. Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-10-09/national-change-in-down-syndrome-reporting-after-complaint/7915222 (accessed February 2023).

17. Campanella N, Edmonds C. Families feel pressured to terminate pregnancies after Down syndrome found in prenatal screening. ABC News. 2021; October 8. Available online at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-08/pressure-mothers-feel-about-babies-with-down-syndrome/100521094 (accessed February 2023).