Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: an undetected and overlooked eating disorder?

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is a relatively newly described eating disorder resulting in nutrient and energy deficiencies, but not driven by body image or weight concerns. There is an urgent need for the education and training of primary healthcare practitioners to better screen for and diagnose ARFID and to become integral members of the multidisciplinary management team.

- Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is associated with weight loss (or a faltering growth trajectory in children), significant nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral feeding or nutritional supplements or evidence of impaired psychosocial functioning.

- ARFID is a relatively novel diagnosis, and there have been few evidence-based studies to inform its epidemiology, aetiology and clinical management.

- Medical complications (e.g. abdominal pain, viral or bacterial infections, gastroesophageal reflux, food allergies or intolerances, gastroenteritis) often prompt patients with ARFID to seek clinical advice from their GPs, who are in an ideal position to help manage the condition.

- Management of ARFID involves psychobehavioural (e.g. ARFID-adapted cognitive behavioural therapy, family-based therapy) and pharmacological (e.g. olanzapine, mirtazapine, D-cycloserine) interventions.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is a complex eating disorder that presents a unique set of challenges in understanding, diagnosing and effectively managing persistent avoidant or restrictive eating behaviours unrelated to body image or weight concerns. This article reviews the diagnostic criteria, aetiology and suggested clinical management for this relatively newly described eating disorder, as well as the important role that GPs can play in overseeing its management.

What is avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder?

ARFID is a relatively new diagnosis in which a heterogeneous group of individuals persistently engage in avoidant or restrictive eating behaviours that are not driven by body image or weight concerns, resulting in nutrient or energy deficiencies.1

ARFID is associated with one or more of the following:

- significant weight loss (or failure to achieve expected growth in children)

- significant nutritional deficiency

- dependence on enteral feeding or nutritional supplements

- marked interference with psychosocial functioning.

Furthermore, the eating disturbance is not attributable to a concurrent medical condition (e.g. allergies), or not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g. anorexia nervosa [AN]), a lack of available food or a cultural practice (e.g. fasting for Ramadan).

ARFID was introduced as a ‘Feeding and Eating Disorder’ in 2013 in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), and in 2018 in the WHO International Classification for Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11).1,2

The DSM-5 does not acknowledge subtypes of ARFID officially, but three core presentations that drive ARFID are described:1,3

- an avoidance of eating or foods based on the sensory characteristics of food (e.g. taste, texture, colour, smell, appearance and temperature)

- an apparent lack of interest in eating or food (e.g. low appetite, forgetting to eat, not finding pleasure in eating)

- a concern about the aversive consequences of eating, often following a traumatic experience associated with eating (e.g. choking, vomiting, gastrointestinal discomfort).

The first driver, sensory-based avoidance, is currently the most reported presentation of ARFID.4 Importantly, however, these core presentations are neither exhaustive nor distinct; rather, they serve as a first step towards capturing and understanding the variety of drivers of food avoidance/restriction.5-8

Epidemiology

Studies on the prevalence of ARFID are limited and have shown varying results, ranging from 1.5% to 64% in clinical eating disorder settings and from less than 1% to 15.5% in the general population.9-16 Hence, the true prevalence rate of ARFID is unknown, but it could be as prevalent as AN or bulimia nervosa (BN).21

ARFID is demographically different from other eating disorders. Compared with AN and BN, ARFID is much more prevalent in young children (under the age of 12 years) and males.10,18 However, anyone can develop ARFID, regardless of age, race, socioeconomic status or gender.7,15,19

Screening

Another important reason for the unknown prevalence of ARFID is the limited availability of screening and assessment tools.11,20 The Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview (PARDI) and PARDI-ARFID Questionnaire (PARDI-AR-Q) have been developed to assess the presenting characteristics and severity of ARFID symptoms (containing questions such as ‘Over the past month, how often have you forgotten to eat or found it difficult to make time to eat?’).21 Screening tools, such as the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen, are also available (containing questions such as ‘I avoid or put off eating because I am afraid of gastrointestinal discomfort, choking or vomiting’, with a rating of their level of agreement required).22 Large-scale studies are needed to fully assess the psychometric properties of these tools.

Complications

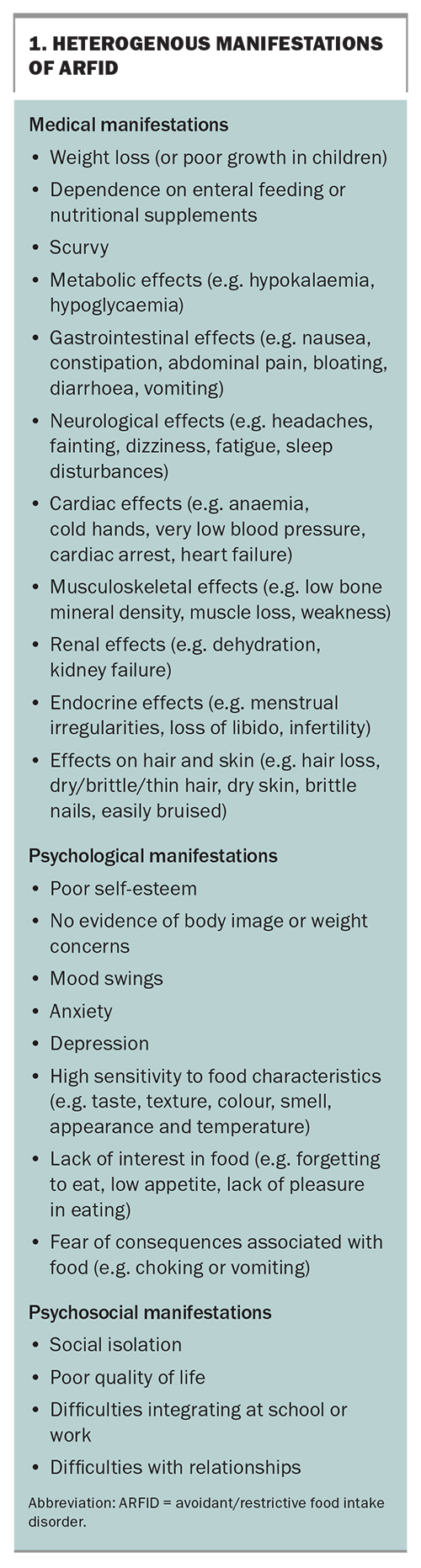

ARFID can lead to various nutritional and energy deficiencies, depending on the specific food preferences and aversions of the individual. Some common deficiencies that may arise from ARFID include protein, fibre, vitamins and minerals (e.g. iron; calcium; vitamins A, B2, B12, C, D, E and K). These deficiencies may result in numerous serious medical, psychological and psychosocial signs and complications.16,18 Therefore, GPs are encouraged to refresh their knowledge on the disorder and its heterogeneous manifestations.18 These may include, but are not limited to, those described in Box 1.

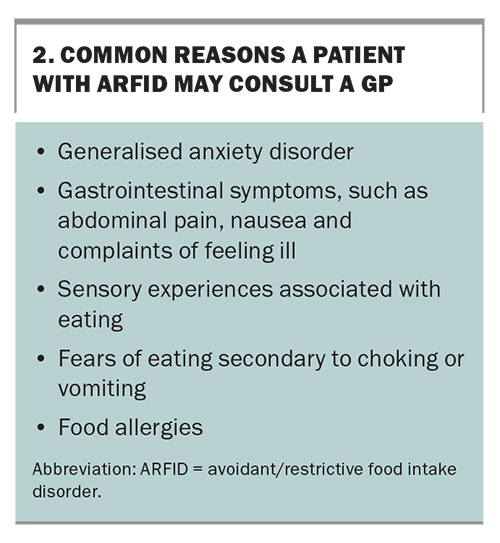

ARFID is clinically different from other eating disorders. Compared with patients with AN or BN, patients with ARFID are more likely to have a comorbid medical condition, commonly including a history of abdominal pain and viral or bacterial infections prior to presentation, gastroesophageal reflux, food allergies and gastroenteritis. Patients with ARFID are also more likely to have an anxiety or other psychiatric disorder, experience a longer length of illness and require enteral feeding.23-26 A possible explanation for the latter is that a typical ARFID diet is limited in protein and vegetables, but high in fat, processed foods, carbohydrates and added sugar.27 Box 2 lists some common reasons a patient with ARFID may consult a GP.

Individuals with ARFID are less likely to be hospitalised than individuals with AN, but this may be because individuals with ARFID present at a younger age with a higher heart rate and a more chronic presentation.23 However, there is now evidence to suggest that once admitted, they often require longer durations of stay.26

In contrast with other eating disorders, ARFID is not associated with body image or weight concerns. However, people with ARFID can present as low in weight as patients with AN and with a similar degree of malnutrition.24,25,28,29

Causes

The varied aetiology of ARFID is not well understood but, as with every eating disorder, it is assumed that it develops from complex interactions between underlying biological, psychological and sociocultural mechanisms.18,31 Given its heterogeneous presentations, the aetiology of ARFID may be even more complex and varied than those of other eating disorders.

The most advanced aetiological model posits that biological abnormalities lead to different manifestations of ARFID that require different treatment interventions. That is, sensory-based presentations are associated with oversensitivity of taste perception, lack-of-interest presentations are associated with differences in the activation of the brain’s appetite-regulating centres (inappropriate homeostatic regulation) and fear-based presentations are associated with hyperactivation of the defence motive system (i.e. hyperactivation of the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex and ventral prefrontal cortex).30

The following risk factors have been reported:4,13,18,31

- presence of neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g. autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and intellectual disability)

- comorbid psychiatric conditions (e.g. anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder)

- comorbid medical conditions (e.g. gastrointestinal disease, metabolic disorder, food allergies or intolerances)

- a history of picky eating and nausea in children.

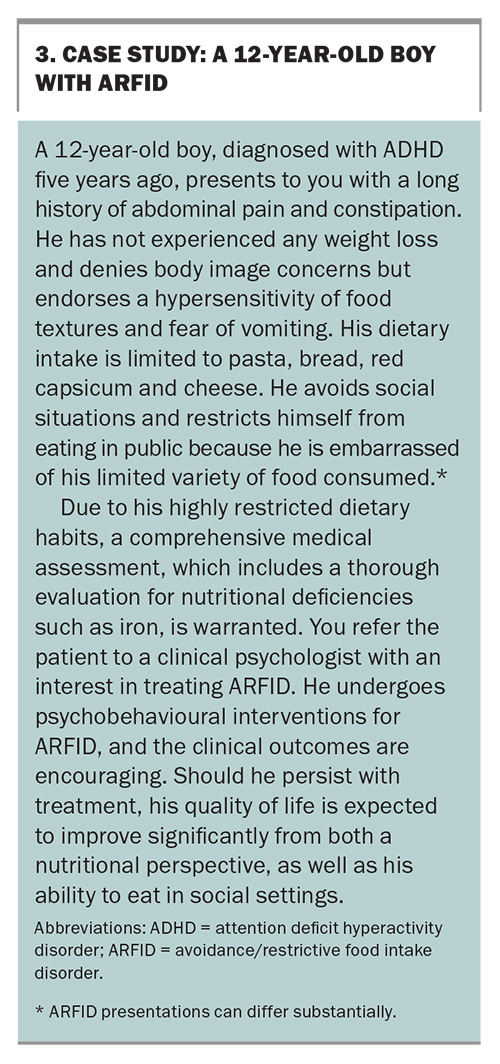

A better understanding of the varied aetiology is warranted to develop effective treatment interventions for ARFID. Box 3 provides a case study involving a presentation of ARFID in a 12-year-old boy.

Treatment interventions

When assessing a patient with ARFID, it is important to assess and consider any differential diagnoses and comorbid conditions. A decision would need to be made regarding which aspects of the presentation should be addressed first. A range of treatments for ARFID are under investigation, but given the disorder’s wide range of presentations and medical, psychological and psychosocial complications, it is unlikely that a one-size-fits-all treatment will ever be established.32

Although largely made up of case reports and small, uncontrolled studies with short follow-up in young children, current literature describes promising findings regarding ARFID-adapted cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT-AR), family-based therapy (FBT) and adjunctive pharmacotherapy.17 However, it is important to note that different presentations may require different interventions and that individually tailored treatment should be considered.

CBT-AR is recommended for all ARFID presentations in those aged 10 years and older who are medically stable, do not have severe developmental disabilities and are accepting at least some food by mouth and not receiving tube feeding. It is designed to reduce nutritional compromise, increase opportunities for exposure to novel foods and reduce negative feelings and predictions about eating. It is a time-limited intervention delivered over 20 to 30 sessions, based on the degree of nutritional compromise and severity. Depending on age, it can be offered as a family-supported or individual version.32-35 CBT-AR is made available to clinicians in Australia, and credentialled psychologists would be aware of those who have the appropriate skills and knowledge to deliver this treatment. The InsideOut Institute, Butterfly Foundation and Connected practitioner databases specify whether a clinician takes ARFID referrals.

FBT, the leading outpatient treatment for adolescents with AN and BN, has shown promising results in treating ARFID in children. It is designed to support caregivers and recovery at home by means of psychoeducation, exposure to nonpreferred foods and increased volume of foods.36

When used as an adjunct to psychobehavioural therapies, several pharmacological interventions show early promise in reducing ARFID behaviours and symptoms. These include:

- olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic associated with weight gain; improved appetite and eating behaviours; and reduced anxiety, depressive and cognitive symptoms32,37,39

- mirtazapine, an antidepressant with appetite-stimulating properties, which has been shown to enhance weight gain and relieve anxiety associated with choking or vomiting39

- D-cycloserine, which is associated with improved eating behaviours (swallowing bites of food more rapidly and experiencing fewer mealtime disruptions).40

Other medications with preliminary evidence of effectiveness include cyproheptadine, risperidone, aripiprazole, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and escitalopram.17 For both psychobehavioural and pharmacological therapies, large-scale randomised controlled trials in both children and adults are warranted to verify the optimal treatment approaches for various ARFID presentations.

Service management

Patients with ARFID often seek clinical advice from their GPs, who are in an ideal position to help manage the condition. However, given its wide range of presentations and medical, psychological and psychosocial complications, GPs should consider a multidisciplinary team approach in which medical and allied healthcare professionals collaborate to conduct patient assessment, consider relevant treatment options and develop an individually tailored treatment plan. Although this approach is widely recognised as best practice for eating disorders, less severe cases may be successfully treated by a single practitioner with expertise in ARFID.3,4,41,42

A multimodal approach, characterised by delivering different treatment interventions for both mind and body together, is recommended as well.41 Although outpatient care is appropriate for most patients with ARFID, there is a need for a continuum of care, ranging from acute inpatient treatment for medically compromised individuals through to outpatient therapy options.17,41 However, to date, there is a lack of clear care pathways and consensus guidelines on its management.

In fact, a recent UK study found that healthcare professionals struggle to identify, diagnose and treat ARFID effectively.43 The report highlights the need for education and training for primary healthcare professionals, and the need for well-co-ordinated, multidisciplinary, ARFID-specific care pathways to appropriately manage the assessment, diagnosis and support for this complex and heterogeneous group of patients.

Large-scale research is needed to evaluate and improve current care pathways and, importantly, establish how care pathways for ARFID should differ from those of other eating disorders, such as AN and BN. Nonetheless, GPs are best placed to

co-ordinate the care of patients with ARFID. Box 4 lists some resources for GPs, as well as parents and carers.

Conclusion

ARFID is a complex, heterogenous eating disorder that is unrelated to body image or weight concerns and can result in significant nutritional deficiencies and psychosocial impairment. Treatment is tailored to each patient and may include psychobehavioural approaches and adjunctive pharmacotherapy. GPs play an essential role in identifying and managing ARFID and co-ordinating care and support for individuals with ARFID. A multidisciplinary approach is often necessary given the wide range of presentations and complications associated with the disorder. Further research is warranted to identify optimal treatment approaches for different ARFID presentations and establish clear care pathways and consensus guidelines for ARFID management. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Ms Rabbering, Dr Crino: None. Professor Touyz has received an MRFF grant from Commonwealth of Australia to investigate the role of psilocybin in the treatment of anorexia nervosa (CIA); royalties for published work from McGraw Hill, Taylor and Francis, and Hogrefe and Huber; public speaking fees from Takeda and Healthed; payment for writing granted to Inside Out from the Government of Victoria; and payment from Psychiatry Reviews. He has also been a plenary invited speaker at the London International Conference on Eating Disorders; and a paid Committee Member for the Technical Advisory Group on Eating Disorders, Department of Health. He is the Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Eating Disorders. Associate Professor Maguire has received an MRFF grant from Commonwealth of Australia to investigate the role of psilocybin in the treatment of anorexia nervosa (CIA); and support to attend the London International Conference of Eating Disorders.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

2. World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 11th revision (ICD-11). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

3. Rienecke RD, Drayton A, Richmond RL, Mammel KA. Adapting treatment in an eating disorder program to meet the needs of patients with ARFID: Three case reports. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2020; 25: 293-303.

4. Bourne L, Bryant-Waugh R, Cook J, Mandy W. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a systematic scoping review of the current literature. Psychiatry Res 2020; 288: 112961.

5. Nitsch A, Knopf E, Manwaring J, Mehler PS. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID): its medical complications and their treatment—an emerging area. Current Pediatrics Reports 2021; 9: 21-29.

6. Duncombe Lowe K, Barnes TL, Martell C, et al. Youth with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: examining differences by age, weight status, and symptom duration. Nutrients 2019; 11: 1955.

7. Ornstein RM, Rosen DS, Mammel KA, et al. Distribution of eating disorders in children and adolescents using the proposed DSM-5 criteria for feeding and eating disorders. J Adolesc Health 2013; 53: 303-305.

8. Dinkler L, Yasumitsu-Lovell K, Eitoku M, et al. Development of a parent-reported screening tool for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID): Initial validation and prevalence in 4-7-year-old Japanese children. Appetite 2022; 168: 105735.

9. Nicely TA, Lane-Loney S, Masciulli E, Hollenbeak CS, Ornstein RM. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a cohort of young patients in day treatment for eating disorders. J Eat Disord 2014; 2: 21.

10. Cooney M, Lieberman M, Guimond T, Katzman DK. Clinical and psychological features of children and adolescents diagnosed with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a pediatric tertiary care eating disorder program: a descriptive study. J Eat Disord 2018; 6: 7.

11. Krom H, van der Sluijs Veer L, van Zundert S, et al. Health related quality of life of infants and children with avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2019; 52: 410-418.

12. Norris ML, Robinson A, Obeid N, Harrison M, Spettigue W, Henderson K. Exploring avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in eating disordered patients: a descriptive study. Int J Eat Disord 2014; 47: 495-499.

13. Hay P, Mitchison D, Collado AEL, González-Chica DA, Stocks N, Touyz S. Burden and health-related quality of life of eating disorders, including avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), in the Australian population. J Eat Disord 2017; 5: 21.

14. Chen YL, Chen WJ, Lin KC, Shen LJ, Gau SS. Prevalence of DSM-5 mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of children in Taiwan: methodology and main findings. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2019; 29: e15.

15. Goncalves S, Vieira Ai, Machado BC, Costa R, Pinheiro J, Conceicao E. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder symptoms in children: associations with child and family variables. Child Health Care 2018; 48: 301-313.

16. Katzman DK, Spettigue W, Agostino H, et al. Incidence and age- and sex-specific differences in the clinical presentation of children and adolescents with avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. JAMA Pediatr 2021; 175: e213861.

17. Bryant-Waugh R, Loomes R, Munuvea A, Rhind C. Towards an evidence-based out-patient care pathway for children and young people with avoidant restrictive food intake disorder. J Behav Cogn Ther 2021; 31: 15-26.

18. Gupta R. Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID)–what is it and what to do with them? J Med Clin Nurs 2021; 2: 1-3.

19. Norris ML, Spettigue WJ, Katzman DK. Update on eating disorders: current perspectives on avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and youth. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016; 12: 213-218.

20. Todisco P. ARFID in adults. In: Manzato E, Cuzzolaro M, Donini LM, eds. Hidden and lesser-known disordered eating behaviors in medical and psychiatric conditions. Springer, Cham; 2022. p. 103-121.

21. Bryant-Waugh R, Stern CM, Dreijer MJ, et al. Preliminary validation of the pica, ARFID and rumination disorder interview ARFID questionnaire (PARDI-AR-Q). J Eat Disord 2022; 10: 179.

22. Zickgraf HF, Ellis JM. Initial validation of the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (NIAS): a measure of three restrictive eating patterns. Appetite 2018; 123: 32-42.

23. Lieberman M, Houser ME, Voyer A, Grady S, Katzman DK. Children with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder and anorexia nervosa in a tertiary care pediatric eating disorder program: a comparative study. Int J Eat Disord 2019; 52: 239-245.

24. Farag F, Sims A, Strudwick K, et al. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorders and autism spectrum disorders: clinical implications for assessment and management. Dev Med Child Neurol 2022; 64: 176-182.

25. Inoue T, Otani R, Iguchi T, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder and autistic traits in children with anorexia nervosa and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Biopsychosoc Med 2021; 15: 1-11.

26. Strandjord SE, Sieke EH, Richmond M, Rome ES. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorders: illness and hospital course in patients hospitalised for nutritional insufficiency. J Adol Health 2021; 57:673-678.

27. Brigham KS, Manzo LD, Eddy KT, Thomas JJ. Evaluation and treatment of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) in adolescents. Curr Pediatr Rep 2018; 6: 107-113.

28. Zimmerman J, Fisher M. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID). current problems. Paediatr Adol Health Care 2017; 47: 95-103.

29. Williams KE, Hendy HM, Field DG, Belousov Y, Riegel K, Harclerode W. Implications of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) on children with feeding problems. Child Health Care 2015; 44: 307-321.

30. Thomas JJ, Lawson, EA, Nicali N, Misra M, Deckersbach T, Eddy KT. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a three dimensional model of neurobiology and implications for etiology and treatment. Curr Psychiatr Rep 2017; 19: 1-9.

31. Coglan L, Otasowie J. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorders: what do we know so far? BJPsychAdvances 2019; 25: 90-98.

32. Couturier J, Isserlin L, Norris M, et al. Canadian practice guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with eating disorders. J Eat Disord 2020; 8: 4.

33. Thomas JJ, Eddy KT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: children, adolescents, and adults. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2018.

34. Aloi M, Sinopoli F, Segura-Garcia C. A case report of an adult male patient with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder treated with CBT. Psychiatria Danubina 2018; 30: 370-373.

35. Brigham KS, Manzo, LD, Eddy, KT, Thomas, JJ. Evaluation and treatment of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) in adolescents. Curr Pediatr Rep 2018; 6: 107-113.

36. Eckhardt S, Martell C, Lowe KD, Le Grange D, EhrenreichMay J. An ARFID case report combining family-based treatment with the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in children. J Eat Disord 2019; 7: 34.

37. Brewerton TD, D’Agostino M. Adjunctive use of olanzapine in the treatment of avoidant restrictive food intake disorder in children and adolescents in an eating disorders program. J Child Adol Psychopharmacol 2017; 27: 920-922.

38. Spettigue, W, Norris, ML., Santos A, Obeid N. Treatment of children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: a case series examining the feasibility of family therapy and adjunctive treatments. J Eat Disord 2018; 6: 20.

39. Gray E, Chen T, Menzel J, Schwartz T, Kaye WH. Mirtazapine and weight gain in avoidant and restrictive food intake disorder. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatr 2018; 57: 288-289.

40. Sharp W, Allen A, Stubbs K, et al. Successful pharmacotherapy for the treatment of severe feeding aversion with mechanistic insights from cross-species neuronal remodeling. Transl Psychiatr 2017; 7: e1157.

41. Eddy KT, Harshman SG, Becker KR, et al. Radcliffe ARFID Workgroup: toward operationalization of research diagnostic criteria and directions for the field. Int J Eat Disord 2019; 52: 361-366.

42. Hay P. Current approach to eating disorders: a clinical update. Intern Med J 2020; 50: 24-29.

43. Harrison A. Falling through the cracks: UK health professionals’ perspective of diagnosis and treatment for children and adolescents with avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder. Child Care Pract 2021. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2021.1958751.