Swollen legs: a diagnostic and management update

Chronic limb oedema can have a wide variety of causes. An accurate diagnosis can guide effective management. In addition to the treatment of any underlying cause, the principles of lymphoedema management can be applied to improve symptoms, reduce complications and improve quality of life for patients, regardless of the cause of chronic oedema.

- Chronic oedema is defined as persistent swelling that is present for more than three months, regardless of its cause.

- Chronic leg oedema is a prevalent health condition that impacts on patients’ function and quality of life, and is associated with complications such as chronic wounds and cellulitis.

- The lymphatic system has a key role in interstitial fluid homeostasis and chronic oedema.

- An accurate diagnosis of the cause of chronic lower limb swelling is necessary to guide management.

- When chronic oedema persists despite treatment of the causative condition, other effective management strategies can reduce complications and improve quality of life.

The causes of swollen legs are numerous. Diagnostically, most of these can be evaluated for by clinical assessment (including medical and family history, and physical examination) and investigations guided by the clinical assessment. Conversely, disease progression and decline in quality of life can occur in patients if there is a lack of an accurate diagnosis; dismissal of patient concerns; misunderstanding of the physical, psychological and social impacts of the swelling; and default use of diuretics without understanding the cause.1,2 Lower limb lymphoedema in cancer survivors is also associated with additional negative impacts on quality of life.3

Globally, chronic oedema and lymphoedema have been neglected healthcare issues.4 LIMPRINT, a 2019 epidemiology study in Australia, suggested that about a quarter of patients in hospitals and community aged care services have chronic limb swelling. In wound treatment centres, 100% of participants were found to have swelling.5 More than 50% of cases involved the lower limbs, and almost 20% of people had experienced at least one episode of cellulitis in the past year. Interestingly, more than 90% of cases are not cancer-related lymphoedema. Despite these high prevalence rates, most Australian medical graduates still perceive their understanding of chronic oedema and lymphoedema to be low.6,7

Swelling is a manifestation of physiological haemodynamic dysfunction, both as a symptom and consequence of physiological changes that require a definitive objective diagnosis and targeted response. Modern advancements in science and research have altered our understanding of the key role of the lymphatic system in the return of interstitial fluid to the vascular system. These changes need to be recognised to holistically manage a person with chronic oedema or lymphoedema.

This article differentiates between the terms chronic oedema and lymphoedema, and provides an update on contemporary evidence for the assessment, investigation and diagnosis of patients with lower limb swelling to ensure effective management and to reduce or avoid the secondary consequences of chronic oedema or lymphoedema. This article also discusses investigation and management of lymphoedema in more detail.

How and why a patient may present with swollen legs

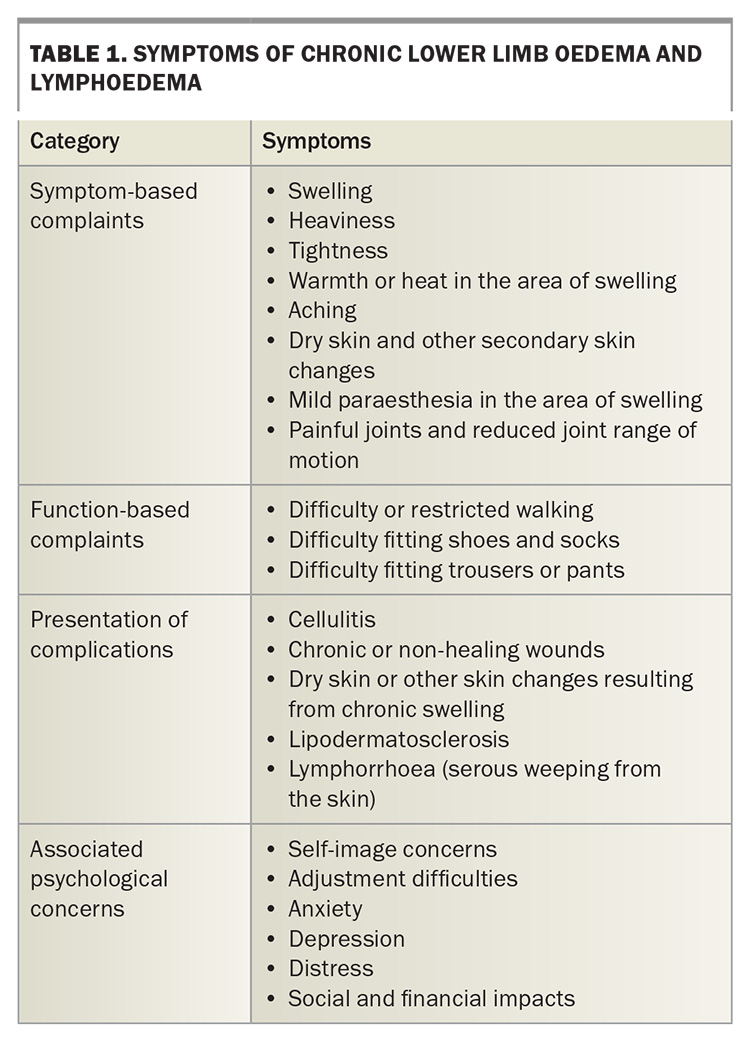

Patients with peripheral oedema may present with a variety of symptoms, such as leg swelling, heaviness, tightness or aching (Table 1). The presenting symptoms and their severity, duration and location may differ between patients, as may any associated symptoms and the impact of the swelling on the patient’s life. Some patients will present with clear evidence of a causative condition (e.g. cardiac, renal or hepatic dysfunction), whereas others may simply present with worsening leg symptoms. Patients may report physical challenges because of the swelling, such as difficulties putting on shoes, fitting into clothing or walking. Symptoms may be relatively new or longstanding. Some patients may not present until they have a complication from the swelling, such as wounds, cellulitis or a leakage from the skin of the affected leg (lymphorrhoea).

The complaint of leg swelling should not be ignored or trivialised. It could be a sign of an underlying condition requiring treatment and it is also a condition in and of itself, with management options that can improve the patient’s quality of life. Chronic oedema can have negative psychosocial impacts on patients in both the cancer and non-cancer populations. Patients may experience psychological distress, anxiety, depression, adjustment difficulties and self-image concerns.8,9

Lymphoedema and chronic oedema: what is the difference?

The definition and understanding of the term lymphoedema have been numerous and variable over the years, with instances of it being used as a clinical diagnosis for cases of chronic swelling. It is a chronic condition caused by impaired lymphatic system function that is characterised by the accumulation of lymphatic fluid in the affected body part (typically legs or arms).10 It can be primary (when a person is born with a lymphatic malformation) or secondary (acquired, e.g. following cancer treatments).

The International Lymphedema Framework have recommended to adopt the term chronic oedema as an umbrella term to describe all persistent oedema that has been present for more than three months, regardless of its cause.4,10,11 The concept of chronic oedema lymphatic deficiency recognises that all persistent swelling has a lymphatic component and acknowledges the role of the lymphatic system in interstitial fluid homeostasis.12 This idea is best described by the Revised Starling Principle.13,14

The Revised Starling Principle

The Starling Principle first described how microvascular fluid exchange occurred at the capillary bed. Earnest Starling’s original theory involved gradient-based movement of fluid through semi-permeable capillaries because of differences in hydrostatic and oncotic pressures, with filtration of fluid into the interstitium from the arterioles and reabsorption of interstitial fluid into the venules. The lymphatic system was responsible for collecting any residual interstitial fluid back into circulation. However, a major element that was missing in Starling’s principle was the endothelial glycocalyx.15-17 This carbohydrate-rich layer within the capillary bed resists reabsorption of interstitial fluid into the capillary. Therefore, the lymphatic system is almost entirely responsible for collecting and returning all interstitial fluid back into cardiovascular circulation and is more important in maintenance of fluid homeostasis than first postulated.18 The Revised Starling Principle takes this new finding into account.18

Approach to diagnosis

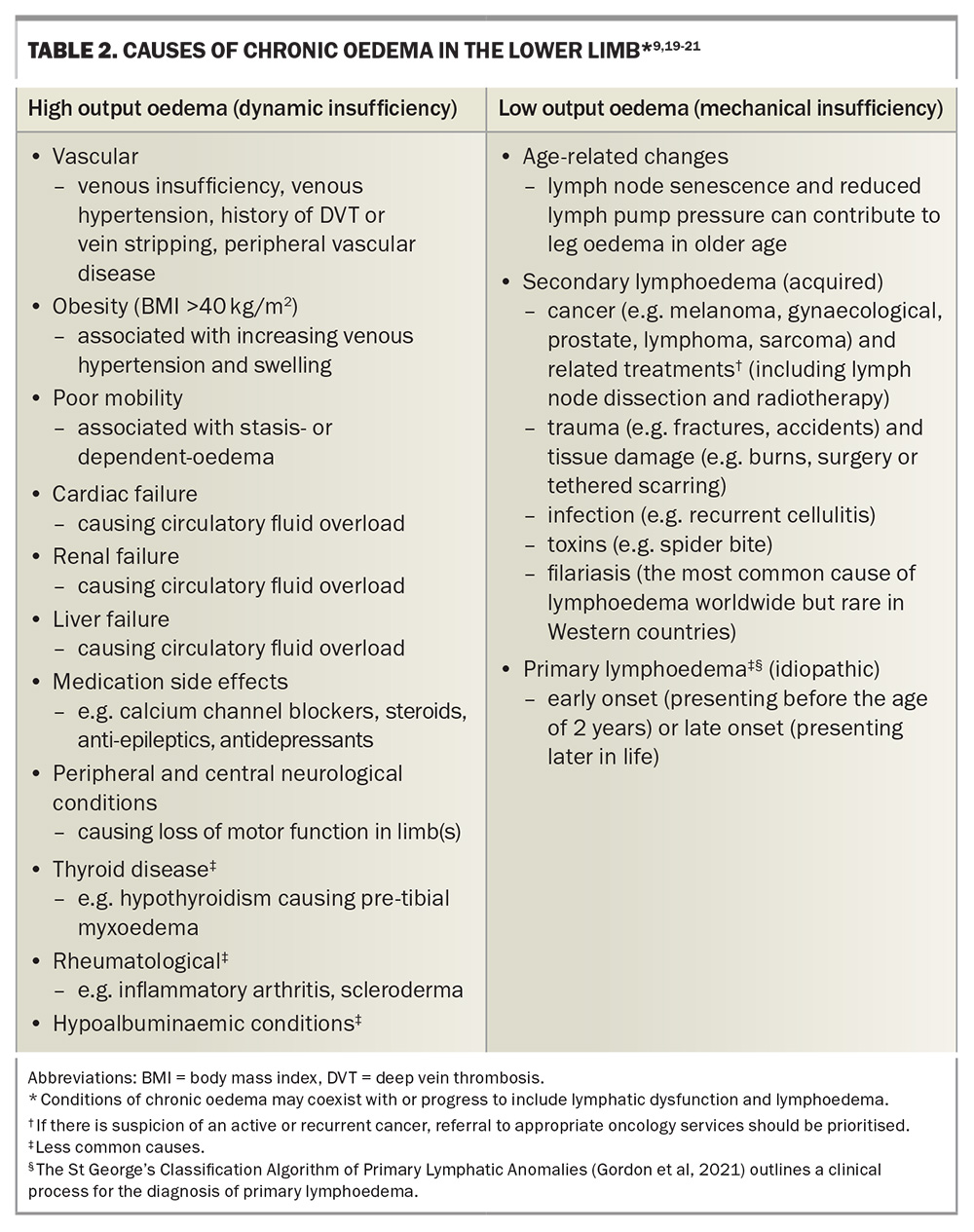

To determine the cause of chronic oedema, one approach is to consider whether a patient has excessive capillary filtration into the interstitial space (high output oedema or dynamic insufficiency, e.g. right heart failure), affected lymphatic absorption or flow (low output oedema or mechanical insufficiency, e.g. primary or secondary lymphoedema), or a combination of both (mixed oedema or combined insufficiency).4,9

It is important to undertake a detailed history about presenting symptoms and their onset, as well as to identify risk factors for potential causes. In Australia, over 90% of cases of chronic lower limb oedema are from non-cancer-related causes, with venous disease being the most common, followed by immobility and obesity.5 Table 2 summarises the common and less common causes of chronic oedema in the lower limb. In general, cases of high output oedema are more common than low output oedema. Systemic causes of peripheral oedema more often result in bilateral leg swelling (e.g. congestive cardiac failure, medication side effects), whereas anatomical or localised causes more often result in unilateral leg swelling (e.g. venous insufficiency, deep vein thrombosis). Taking a travel history and family history is also important, as detailed further in Table 2.

A full physical examination should be performed, tailored to the patient’s presentation and findings on clinical history. Several special tests to perform during physical examination of patients with chronic oedema are as follows:

- observation for skin changes (e.g. pigmentation, varicose veins, atrophie blanche, ankle flare venous eczema, lipodermatosclerosis, skin hardening, lymphorrhoea and mossy foot)

- pitting test: the thumb is used to apply pressure on the affected area for 30 to 60 seconds and then the depth of the pit assessed

- pinch test: the thumb and index finger are used to pinch the skin; the inability of the skin to be lifted and pinched is suggestive of subcutaneous oedema

- bow-tie test: the thumb and index finger are used to pinch the skin with force applied obliquely, creating a twist (‘bow tie’), assessing for the presence of wrinkles

- Stemmer’s sign: the skin of the dorsal surface at the base of the second digit is pinched. A positive test (a sensitive predictor for lymphoedema), is one in which the skin cannot be pinched. A negative test does not exclude lymphoedema.

Age-related lymphatic changes

As with other body systems, lymphatics also experience age-related changes. The lymphatic collector vessels contain endothelial cells, smooth muscles and collagen fibres with fibroblasts in its walls, which contract rhythmically. Along with the vessels’ one-way valves, this propels lymph flow unidirectionally.22 As a person ages, there is remodelling of the vessel wall, with decreased muscle cells and increased lymphatic diameter, resulting in contractile dysfunction.

There are further age-related chemical changes associated with the regulation of nitrous oxide, which also has a role in lymphatic contractility. Nitrous oxide is important in the self-regulatory adjustment of lymphatic vessels to adapt lymphatic filling and contraction activity based on the body’s demands. With age, lymphatic vessels have reduced adaptability to manage increased lymphatic load.23

Other additional age-related cellular changes are proposed to cause hyperpermeability of lymphatic vessels and affect the ability to recruit immune cells in response to infection and acute inflammation.24 Lymph node senescence, referring to the structural changes of aged lymph nodes, may further explain why older adults have reduced ability to fight infections and prevent the development of metastases.25,26

Red flags

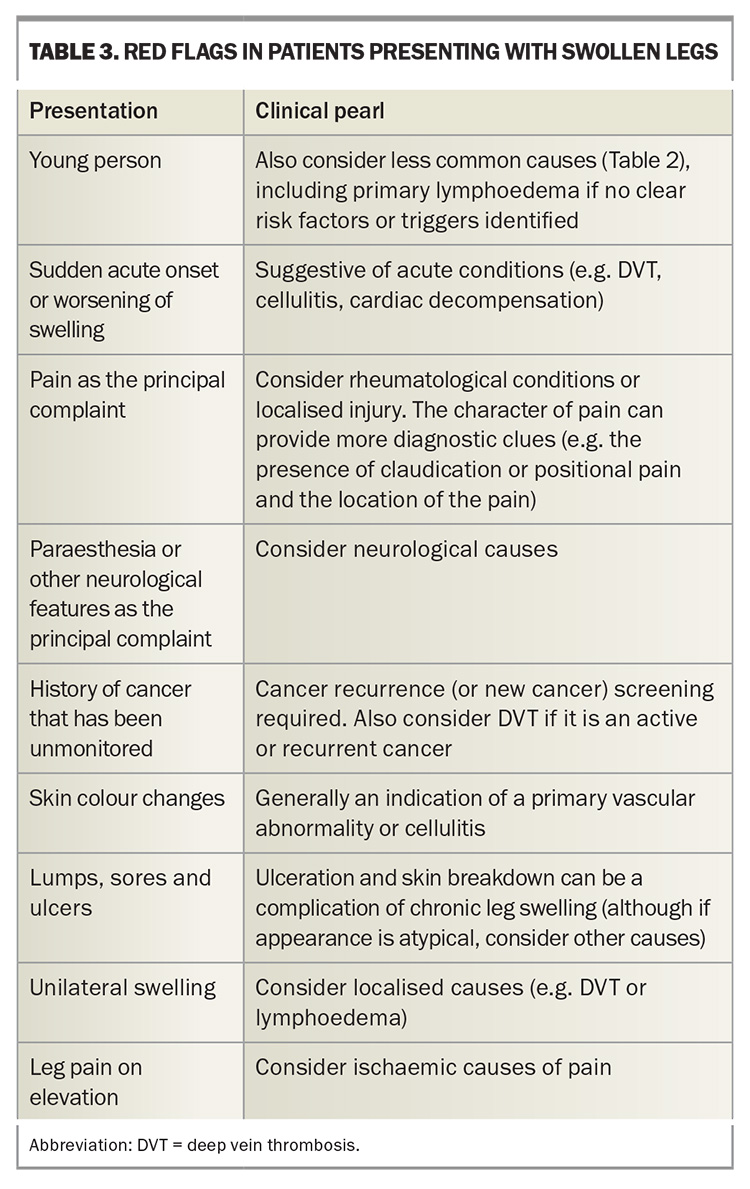

There are certain presentations of leg swelling that should warrant concern for more urgent investigation of potential complications or serious pathology. These are summarised in Table 3. Clinicians also have an important role in antibiotic stewardship and avoiding over-prescribing of antibiotics. Differentiating between different skin conditions, which may appear similar to the patient but are treated quite differently (e.g. cellulitis, lipodermatosclerosis and red leg syndrome), will guide appropriate and effective treatment.26,27

Investigations

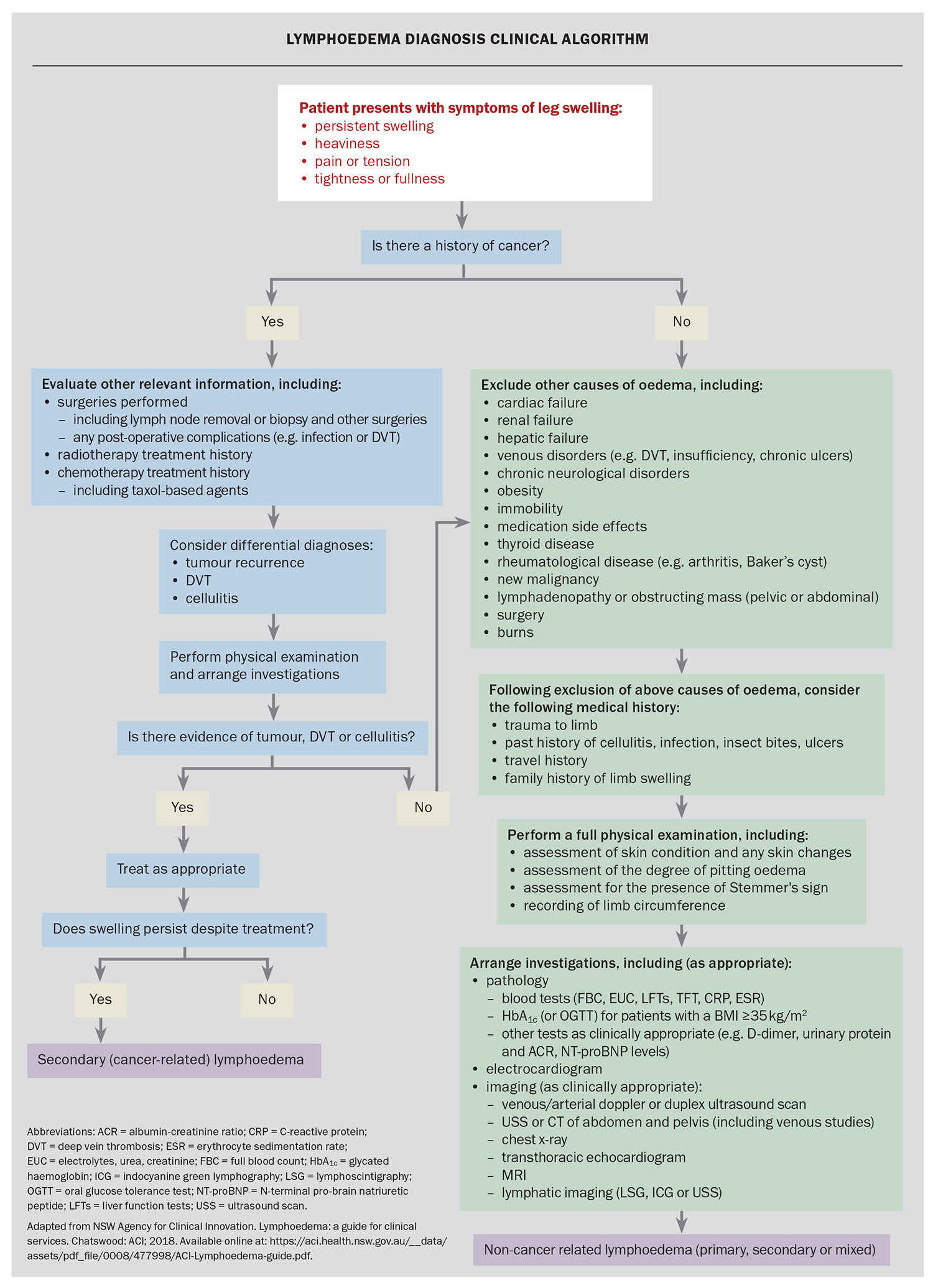

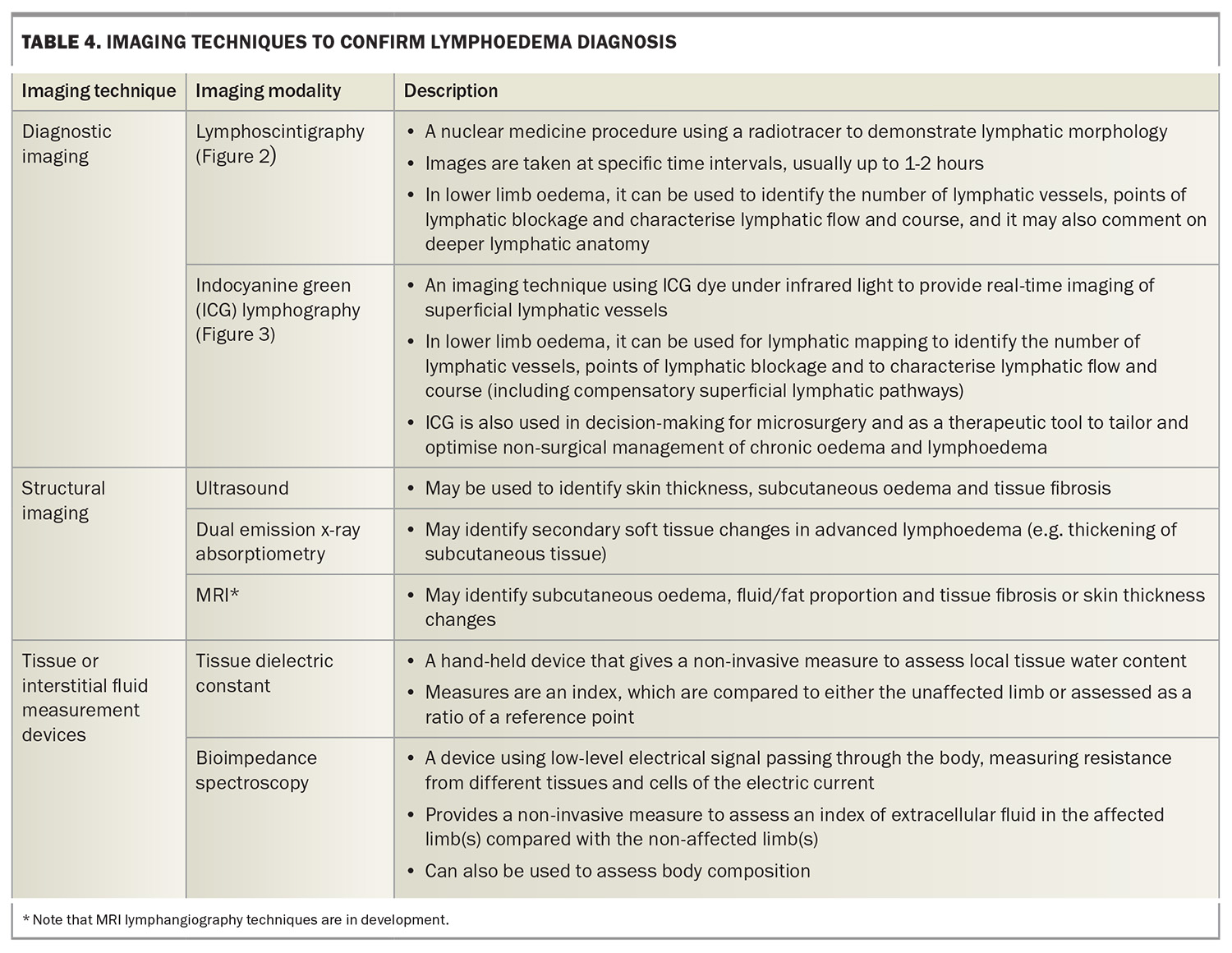

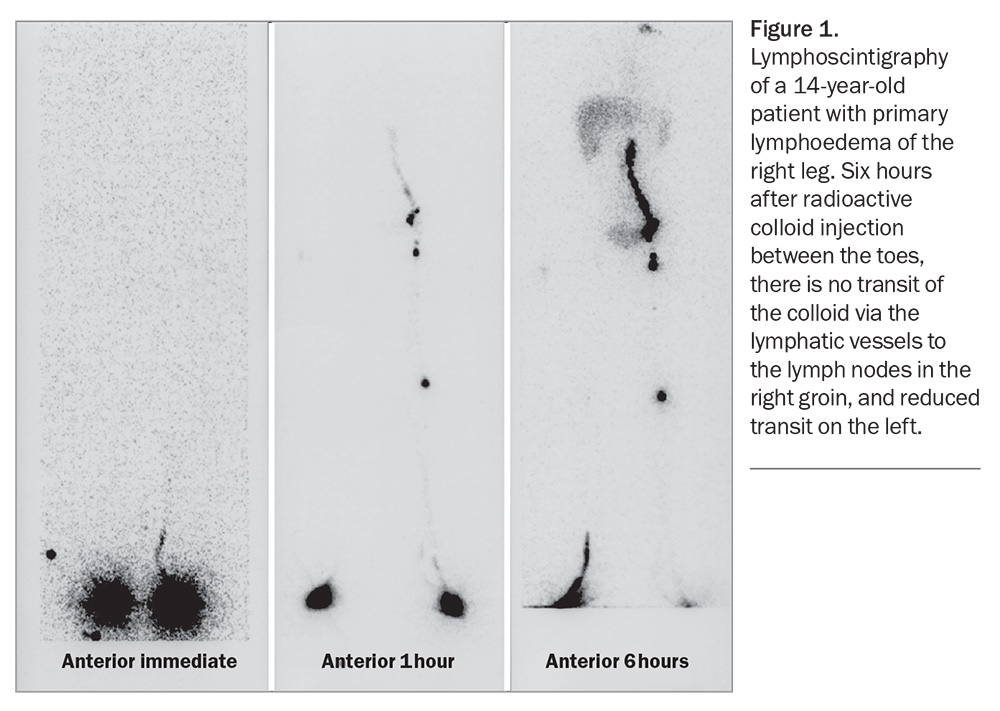

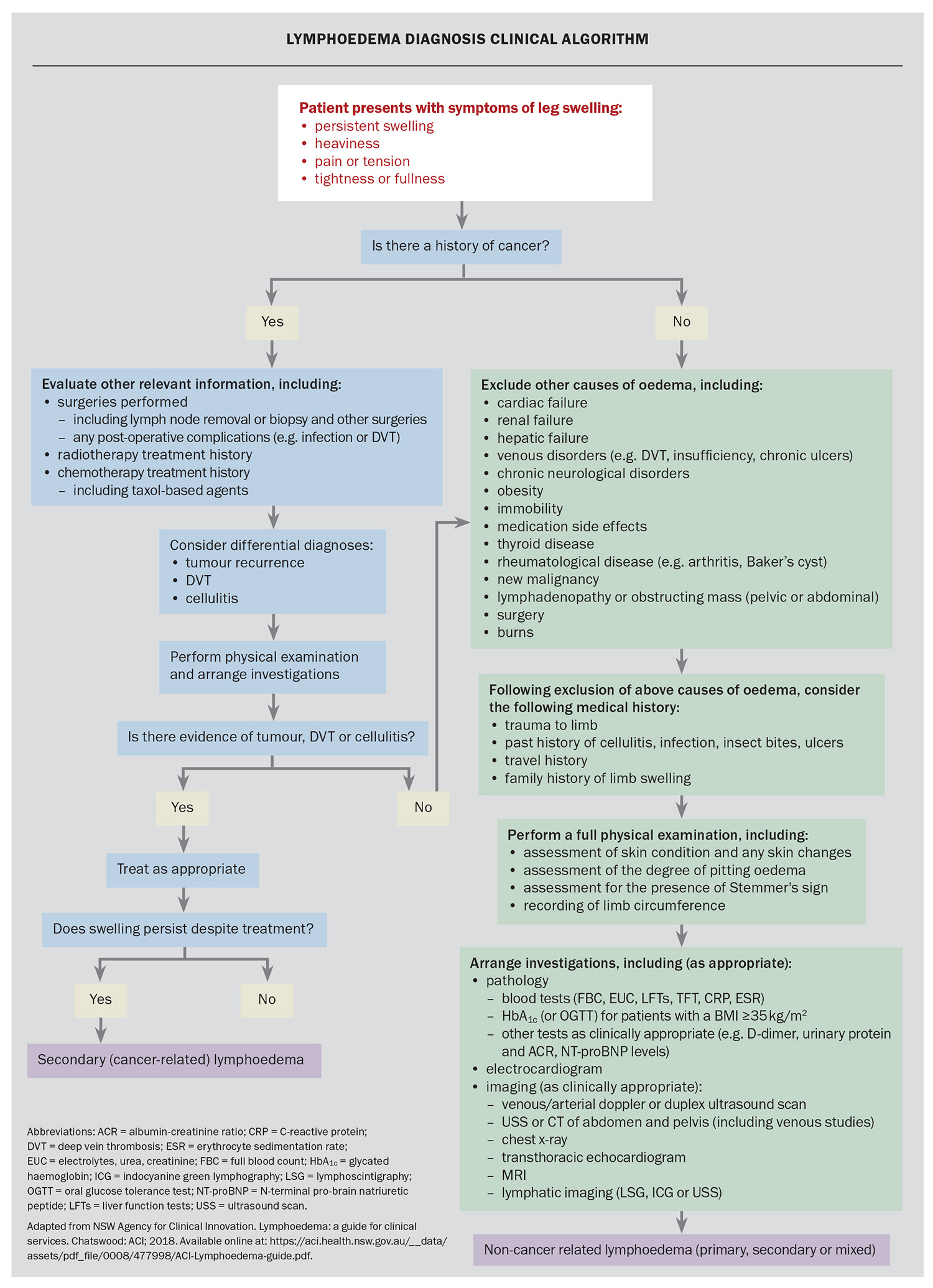

There are numerous pathology and imaging investigations to consider for patients with peripheral oedema. Deciding and prioritising which tests are relevant depends on the findings of the clinical history and physical examination. Investigations are aimed at confirming or ruling out the more common causes of unilateral or bilateral chronic lower limb oedema (Flowchart). Lymphoedema may become the final diagnosis of exclusion. Investigations to assist in diagnosing lymphoedema are described in Table 4, and examples of lymphoscintigraphy and indocyanine green lymphography are provided in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. The NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation offers a decision-making and investigative framework for clinicians to make the diagnosis of lymphoedema. We have adapted this framework with updates on recommended investigations (Flowchart). Although this framework assists with diagnosing lymphoedema, the algorithm also includes assessment and consideration of more common causes of swollen legs, and considers if the person has a cancer history.

Management of persistent chronic oedema and lymphoedema

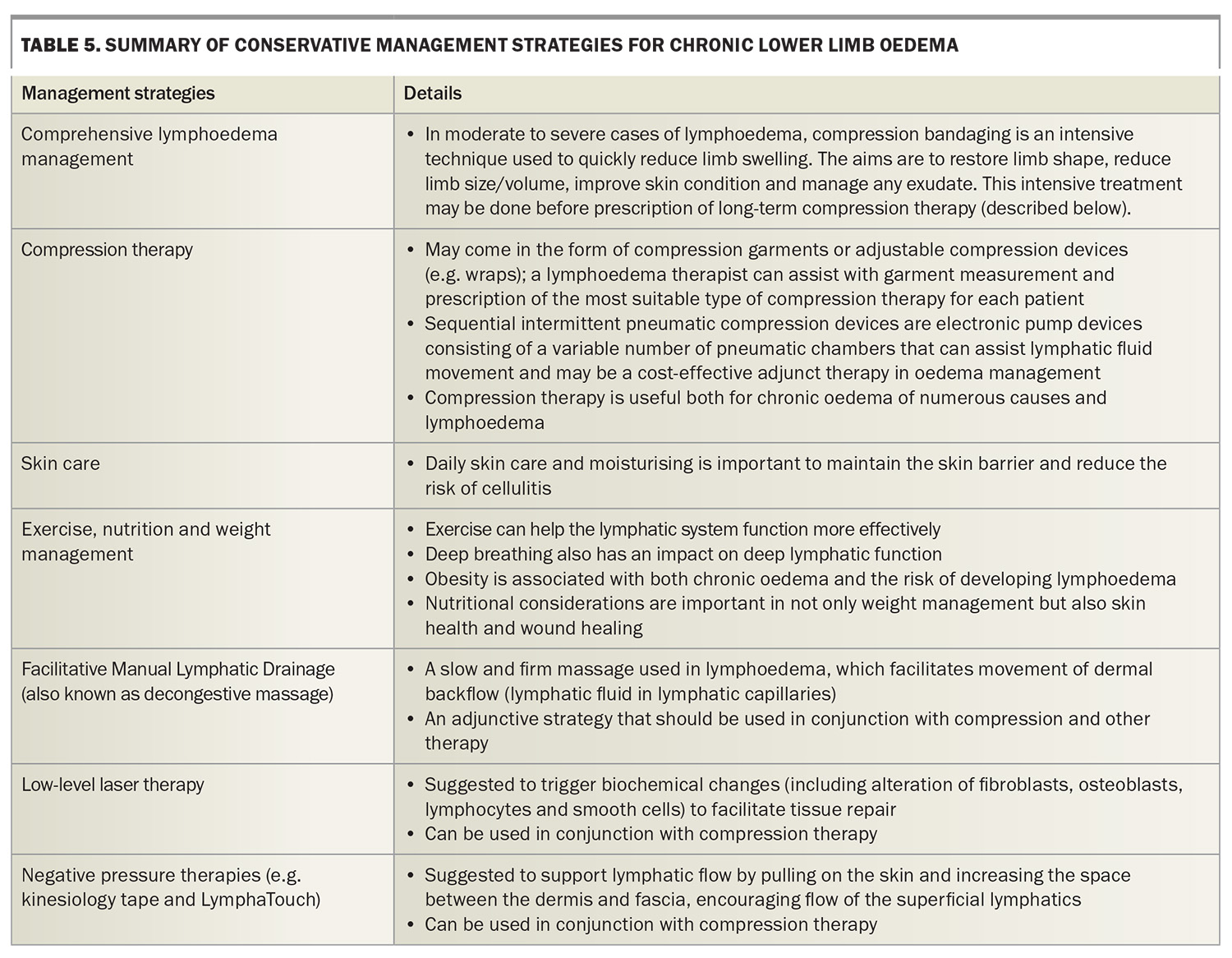

It is important to treat any causes that are reversible. However, in the setting of persistent chronic oedema, when leg swelling is not curable or when residual swelling remains despite treating the cause, the focus then shifts to the management of symptoms and prevention of complications. In these cases, the principles of lymphoedema management can be applied. The techniques developed for lymphoedema are applicable to chronic oedema because of the key role of the lymphatics in all chronic oedemas.

The management of lymphoedema mainly involves non-surgical conservative strategies to reduce tissue fluid load (interstitial fluid). The underlying principles are:

- to facilitate movement of interstitial fluid into lymphatic vessels (thereby becoming lymph)

- to enhance lymphatic transit

- to move lymphatic fluid from areas of congestion to areas of functioning lymphatics, thereby increasing lymphatic transportation

- to reduce and manage the reaccumulation of interstitial fluid.

As with most chronic conditions, empowering the patient to self-manage their condition is key to the long-term care of patients with chronic lower limb oedema. Providing a clear diagnosis, patient education and effective management strategies are pivotal in developing a patient’s self-management skills.28

Adequate management of tissue and lymphatic fluid accumulation and movement can also reduce the risk of cellulitis, improve skin condition associated with chronic swelling and assist with chronic wound healing in an area of chronic oedema.29,30 An accredited lymphoedema practitioner (https://www.lymphoedema.org.au/accreditation-nlpr/find-a-practitioner/) can assist in all aspects of management, including providing patient education, skin care, exercise plan, decongestive massage, pneumatic pump assistance, other adjunct treatments and compression garment recommendations. A summary of conservative management strategies is outlined in Table 5.

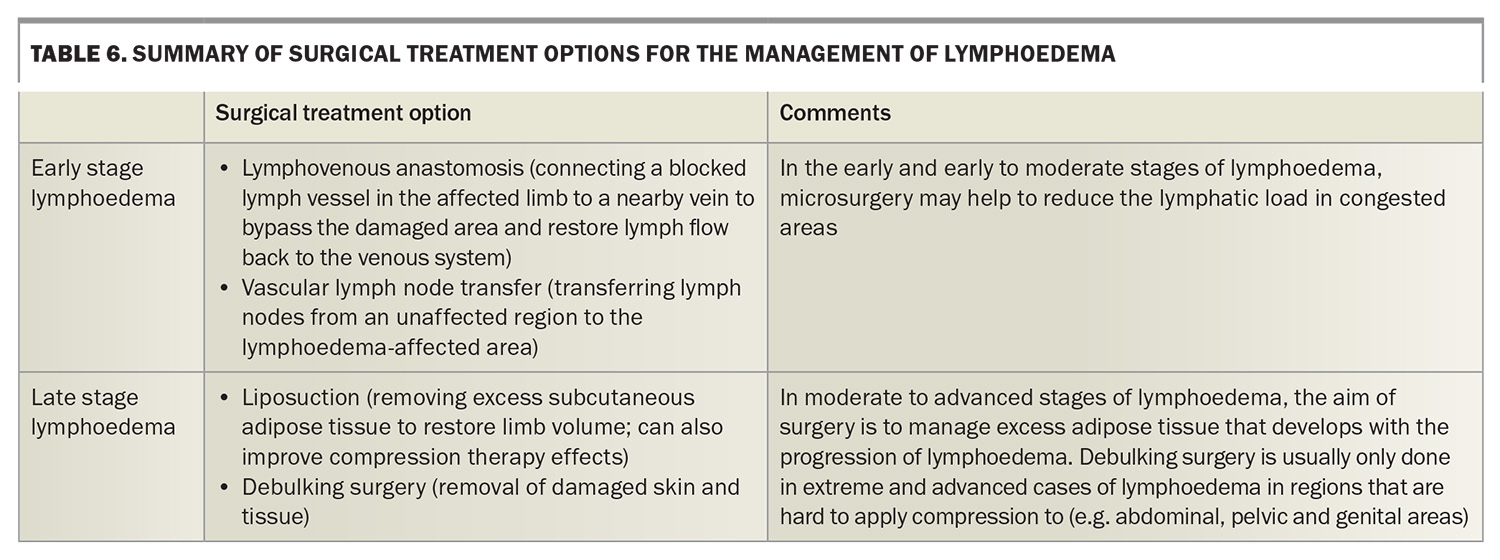

The surgical options available for patients with lymphoedema are limited, as outlined in Table 6. Surgery can enhance or support existing conservative management, reduce the frequency of cellulitis in those prone to cellulitis recurrence and may reduce the likelihood of disease progression in patients with early lymphoedema, although it is not currently considered curative.

Clinicians have an important role in educating patients with chronic oedema about the importance of maintaining good skin care to reduce dry skin, prevent loss of skin integrity, manage fungal infections and minimise the risk of cellulitis. Additionally, regular exercise and weight management will also have an impact on lymphatic function, and on the progression and severity of a patient’s chronic oedema and lymphoedema.21

Referral of a patient with chronic limb oedema to a specialist lymphoedema medical clinic may be warranted if:

- the diagnosis of lymphoedema is unclear and requires a specialist assessment

- the patient is experiencing complications of chronic oedema such as skin breakdown, chronic non-healing wounds or recurrent cellulitis

- there is difficulty establishing adequate oedema control

- the patient is interested in exploring surgical options.

Conclusion

The contemporary understanding of lymphatic function in maintenance of fluid homeostasis confirms that all chronic oedema represents a functional or structural impairment of lymphatic drainage. Successful management of the patient presenting with persistent lower limb swelling first requires an accurate diagnosis, based on findings from a detailed history, examination and relevant investigations. Any reversible underlying cause requires treatment; however, chronic oedema requires management itself to prevent consequent disabling skin deterioration, risk of cellulitis and function effects of reduced mobility and quality of life. Conservative management remains the cornerstone of lymphoedema management and also has a role in chronic oedema management. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Associate Professor Mackie has received payment for a lecture to the Australian Physiotherapy Association. Dr Lam and Dr Geyer: None.

References

1. Lurie F, Malgor RD, Carman T, et al. The American Venous Forum, American Vein and Lymphatic Society and the Society for Vascular Medicine expert opinion consensus on lymphedema diagnosis and treatment. Phlebology 2022; 37: 252-266.

2. Piller, Neil B. Recognition of those at risk of lymphedema, benefits of subclinical detection, and the importance of targeted treatment and management. Indian J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2022; 9: 215.

3. Gjorup, C, Groenvold M, Hendel HW, et al. Health related quality of life in melanoma patients: impact of melanoma related limb lymphoedema. Eur J Cancer 2017; 85: 122-132.

4. Moffatt C, Keeley V, Quere I. The concept of chronic edema – a neglected public health issue and an international response: the LIMPRINT study. Lymphat Res Biol 2019; 17: 121-126.

5. Gordon SJ, Murray SG, Sutton T, et al. LIMPRINT in Australia. Lymphat Res Biol 2019; 17: 173-177.

6. Kruger N, Plinsinga ML, Noble-Jones R, Piller N, Keeley V, Hayes SC. The lymphatic system, lymphoedema, and medical curricula-survey of Australian medical graduates. Cancers (Basel) 2022; 14: 6219.

7. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Towards an estimate of the prevalence of lymphoedema in Australia: a data source scoping report. Canberra: AIHW. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-disease/prevalence-of-lymphoedema-in-australia/summary (accessed May 2024).

8. Kopanoglu T. Design for empowerment: supporting the self-management of people living with a chronic condition (lymphoedema) by design. Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff: 2023. Available online at: https://figshare.cardiffmet.ac.uk/articles/thesis/Design_for_empowerment_

Supporting_the_selfmanagement_of_people_living_with_a_chronic_condition_

lymphoedema_by_design/22117967/1 (accessed May 2024).

9. Executive Committee of the International Society of Lymphology. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Lymphedema: 2020 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 2020; 53: 3-19.

10. Australian Institute of Lymphoedema. What is lymphoedema and chronic oedema? Australian Institute of Lymphoedema: 2024. Available online at: https://instituteoflymphoedema.com.au/about/lymphoedema-and-chronic-oedemas (accessed May 2024).

11. Keast DH, Despatis M, Allen JO, Brassard A. Chronic oedema/lymphoedema: under-recognised and under-treated. Int Wound J 2015; 12: 328-333.

12. Ho YC, Srinivasan RS. Lymphatic vasculature in energy homeostasis and obesity. Front Physiol 2020; 11: 3.

13. Levick JR, Michel CC. Microvascular fluid exchange and the revised Starling principle. Cardiovasc Res 2010; 87: 198-210.

14. Becker BF, Chappell D, Jacob M. Endothelial glycocalyx and coronary vascular permeability: the fringe benefit. Basic Res Cardiol 2010; 105: 687-701.

15. Danielli JF. Capillary permeability and oedema in the perfused frog. Journal of Physiology 1940; 98: 109-129.

16. Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gaehtgens P. The endothelial surface layer. Pflugers Arch 2000; 440: 653-666.

17. Reitsma S, Slaaf DW, Vink H, van Zandvoort MA, oude Egbrink MG. The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflugers Arch 2007; 454: 345-359.

18. Brennan A. Revising the Starling principle: the importance of the glycocalyx. New York: Lymphatic Education & Research Network; 2019. Available online at: https://lymphaticnetwork.org/news-events/revising-the-starling-principle-the-importance-of-the-glycocalyx (accessed May 2024).

19. Gordon K, Mortimer PS, van Zanten M, Jeffery S, Ostergaard P, Mansour S. The St George’s classification algorithm of primary lymphatic anomalies. Lymphat Res Biol 2021; 19: 25-30.

20. NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. Lymphoedema: a guide for clinical services. Chatswood: ACI; 2018. Available online at: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/477998/ACI-Lymphoedema-guide.pdf (accessed May 2024).

21. Lymphoedema Framework. Best Practice for the Management of Lympheodema. International consensus. London: MEP Ltd, 2006. Available online at: https://www.lympho.org/uploads/files/files/Best_practice.pdf (accessed May 2024).

22. Suami H, Scaglioni MF. Anatomy of the lymphatic system and the lymphosome concept with reference to lymphedema. Semin Plast Surg 2018; 32: 5-11.

23. Shang T, Liang J, Kapron CM, Liu J. Pathophysiology of aged lymphatic vessels. Aging (Albany NY) 2019; 11: 6602-6613.

24. De Jong T, Semmelink JF, Bolt JW, et al. Premature aging in lymph node stromal cells of patients with rheumatoid arthritis partly restored by Dasatinib treatment. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2023; 82: 12-13.

25. Filelfi SL, Onorato A, Brix B, Goswami N. Lymphatic senescence: current updates and perspectives. Biology (Basel) 2021; 10: 293.

26. Ellwell R. Differential diagnosis in patients with red legs: red legs pathway to guide decision making. Br J Community Nurs 2020; 25: S32-S35.

27. Moore Z, O’Brien G, Collier M et al. Patients presenting with ‘red legs’: Differential diagnosis and the role of compression. London: Wounds International; 2022. Available online at: https://www.woundsinternational.com (accessed May 2024).

28. Grady PA, Gough LL. Self-management: a comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. Am J Public Health 2014; 104: e25-e31.

29. Webb E, Neeman T, Bowden FJ, Gaida J, Mumford V, Bissett B. Compression therapy to prevent recurrent cellulitis of the leg. N Engl J Med 2020; 383: 630-639.

30. Pigott A, Piller N, Phillips J. The use of compression in the management of lymphoedema. Position paper. Beaumaris: Australasian Lymphology Association; 2021.