Ambulatory rehabilitation: a model of care for the community

Rehabilitation can benefit both the individual with a disability and the community at large. The ideal setting and model of rehabilitation depends on the patient’s condition, psychosocial and environmental factors, their personal goals and access to funding for required services. Several rehabilitation services are available to support primary care physicians in managing adult patients with a disability.

- Illness and injury may cause impairment and disability that is temporary or permanent.

- Disability due to chronic disease will likely increase as medicine and technology improve, the population ages and diseases, such as cancer and autoimmune and neurological conditions, become increasingly survivable.

- Rehabilitation can improve health outcomes, optimise function and promote independence in people with a disability.

- A multidisciplinary rehabilitation team, often led and co-ordinated by a clinician, has an important role in the success of any rehabilitative treatment plan.

- Rehabilitative care can occur in the hospital (inpatient, in-reach or outreach setting) or in the community (ambulatory care as outpatient, in hospital or home-based rehabilitation), and should be tailored according to the patient’s specific condition and personal and environmental factors.

- Several different ambulatory rehabilitation services to help support patients with a disability are available for GPs to access or refer to in the community.

Over 4 million people in Australia identify as having some form of disability. Of this group, about 50% are of working age; between 15 and 64 years.1 The spectrum of disability is broad and is associated with reduced quality of life (QOL) and loss of independence, which can range from being unable to engage in paid employment, to requiring significant levels of assistance on a day-to-day basis.2,3 Traditionally, people with disabilities were understood to be those who were born with congenital and developmental disabilities, or who acquired disability through injury later in life, such as stroke, spinal cord or brain injury. However, as the population ages and medicine and technology advance, the prevalence of disability will continue to rise due to an increase in chronic health conditions, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and mental health disorders, and improved survival of diseases, such as cancer and autoimmune and neurological conditions.4

For people with a disability, rehabilitation improves health outcomes and QOL; reduces disease burden, burden of care, healthcare and social service costs; and improves community participation, and can contribute to the health and wellbeing of the community.3 These goals are in keeping with Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021-2031.5 Rehabilitative care can be provided in two main settings: in hospital, on acute or subacute wards; or in the community, known as ambulatory care.

This article explores types of ambulatory rehabilitation that primary care physicians are able to access for their patients with a disability. Additionally, for those unable to access rehabilitation services, which may be the case in rural and remote communities, this article may serve as a guide to providing rehabilitation in the primary care setting.

GPs have a crucial role in helping people living with a disability feel validated and supported as important and contributing members of the community by communicating to, advocating for and trying to understand the needs of this population. In so doing, they actively redress discrimination and stigma and boost the sense of independence of people living with disabilities.

‘Disability need not be an obstacle to success.’

Professor Stephen W. Hawking

What is disability?

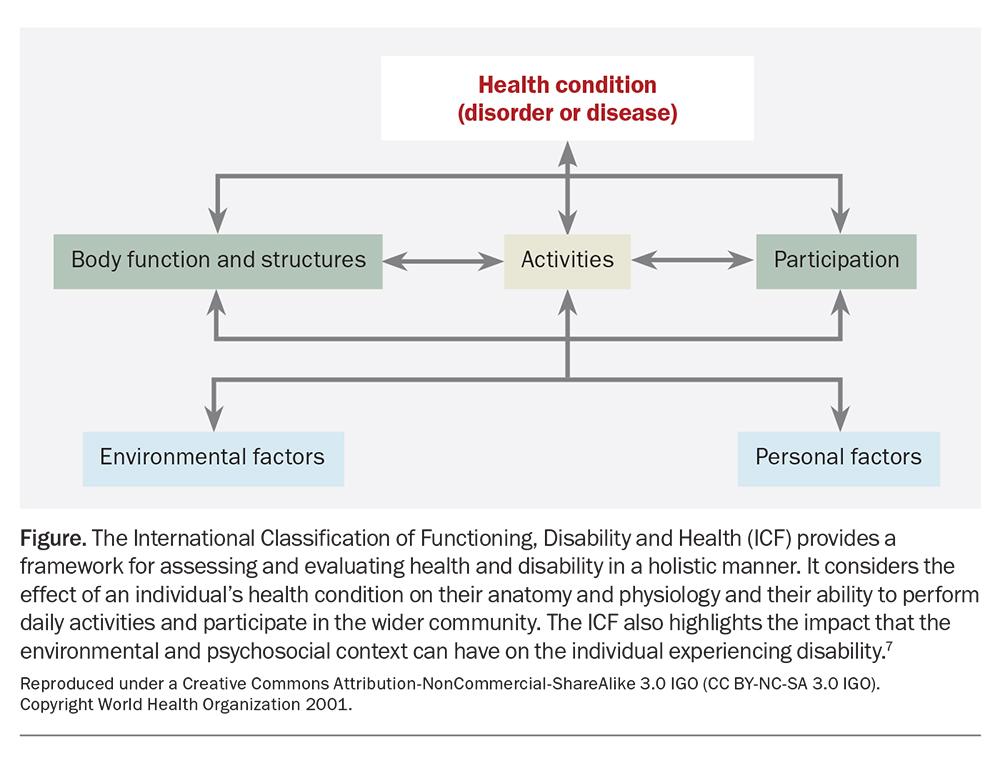

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), as outlined by the WHO, defines disability as the overarching term describing impairments (loss and changes in body function) resulting in activity limitations (difficulty completing essential daily activities) and participation restrictions (effect on access and interaction within the community).6 Disability may be physical, intellectual, cognitive or psychological in nature, or a combination. It may be temporary, chronic and stagnant, fluctuate over time or progressively worsening. Additionally, people with a disability are prone to age-related changes that will affect the severity of their disability.

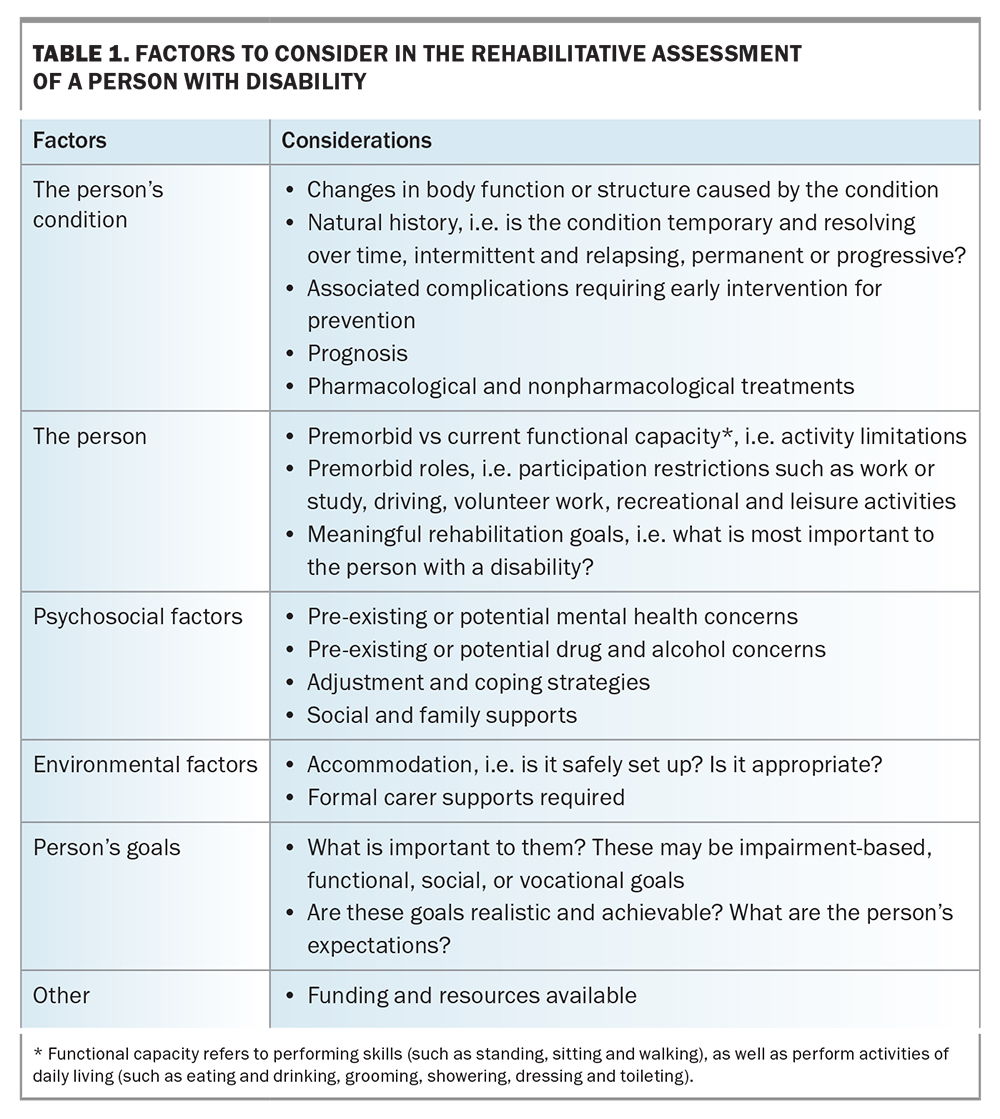

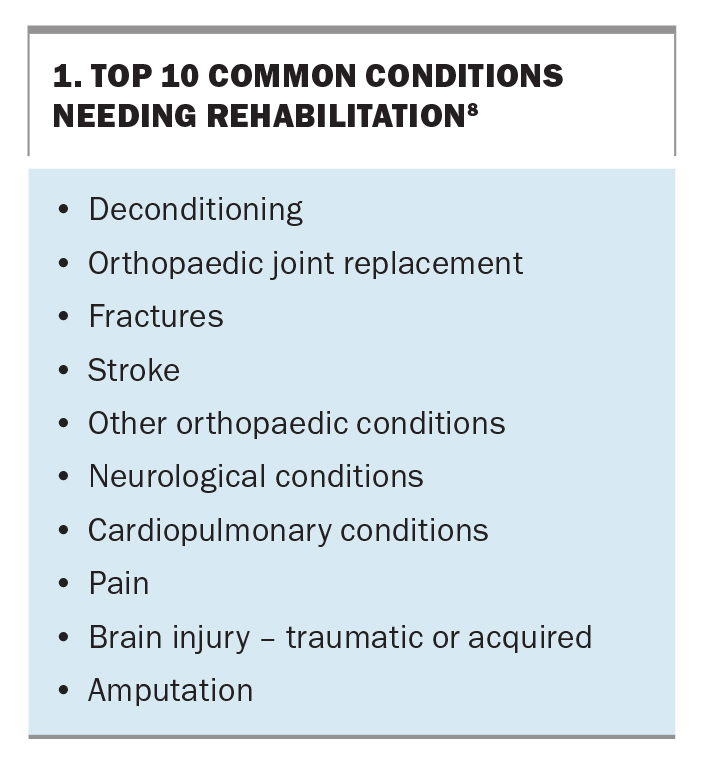

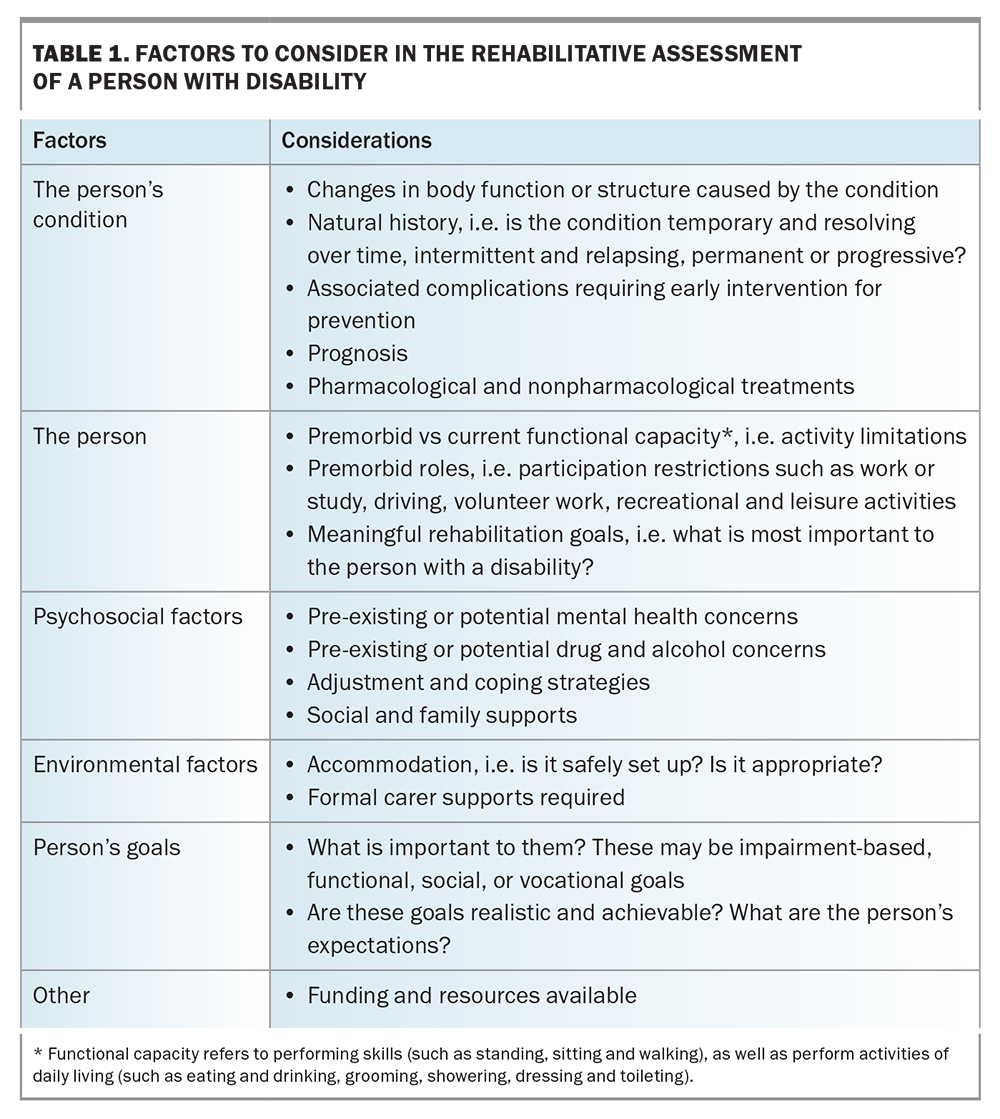

The ICF model highlights the important interplay between a person’s health condition and the impact of personal and environmental factors, as outlined in Table 1 and the Figure.7 Rehabilitation provides a holistic approach to assist people who have a disability achieve and maintain optimal functioning within their individual environment and restore or maximise function across physical, psychological, social and vocational domains. Several types of conditions causing disability often benefit from rehabilitative care, with deconditioning and disability secondary to surgery or medical illness the most common cause, as listed in Box 1.8

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation

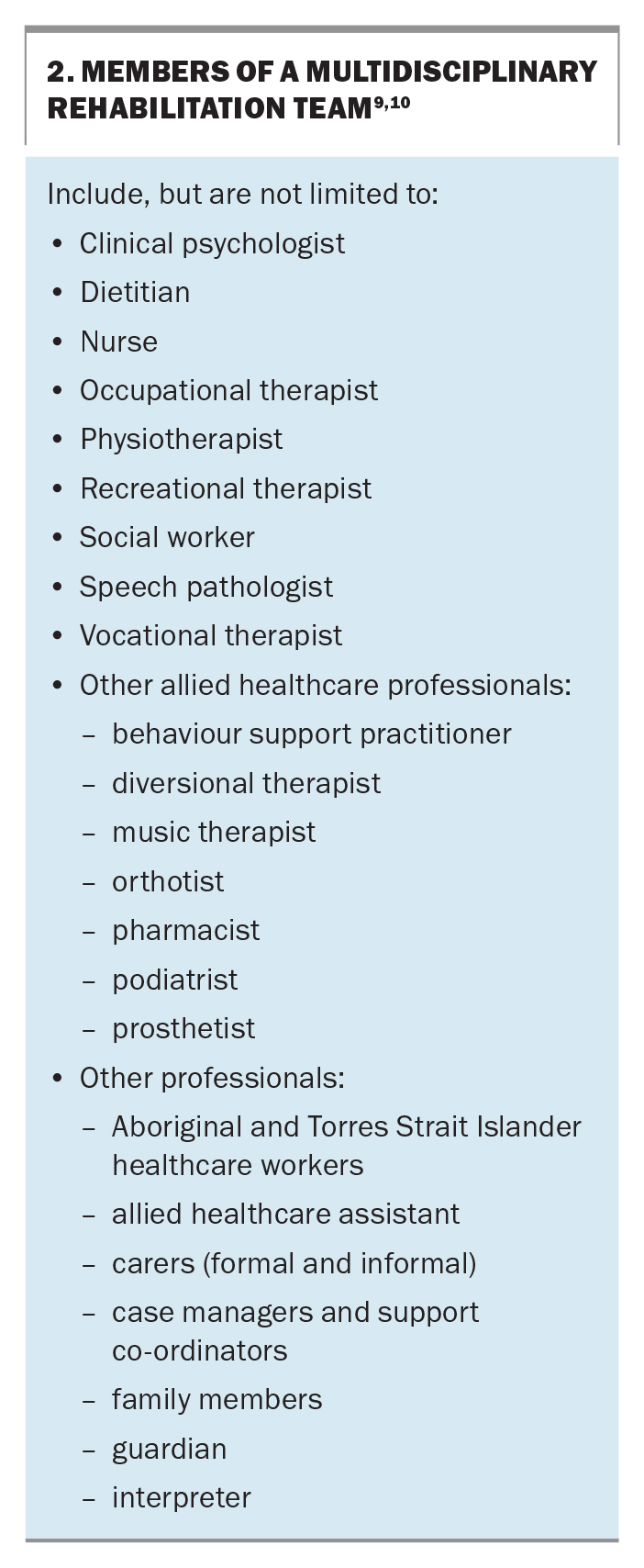

The multidisciplinary rehabilitation team (MRT) may be made up of different healthcare professionals, each responsible for a different facet of treatment (Box 2).9,10 Members of the MRT frequently engage with and request input from a patient’s carers (formal and informal), guardian or family members, as well as third parties (e.g. case managers or support co-ordinators), in finding collateral information and implementing care and therapy plans. Engagement of these stakeholders is often vital in the success of any treatment plan. Over time, the make-up of the MRT may change, based on the patient’s condition, capacity, needs and personal goals.

The role of the clinician

Multidisciplinary rehabilitation is usually led and co-ordinated by a clinician. This may be the primary care physician, rehabilitation physician or geriatrician in patients of older age with multiple comorbidities. Patients with chronic and complex conditions benefit from engaging a rehabilitation physician who specialises in diagnosing, assessing and managing individuals with a complex disability.9

The clinician’s approach to a rehabilitative assessment is outlined in Table 1. This assessment provides context to the individual’s disability and outlines where treatment should be prioritised to achieve meaningful goals for the patient.3 The clinician’s knowledge of the condition, combined with the assessment findings, guides the approach best suited to the patient to optimise their function and QOL. The five main approaches are:

- prevention of the loss of function

- slowing the rate of loss of function

- improvement or restoration of function

- compensation for loss of function

- maintenance of current function.11

The clinician can then refer and engage the necessary MRT members. A thorough understanding of the social and environmental factors that may enhance or obstruct the patient’s progress is important, and may influence patient participation and outcome. The clinician should also understand the resources and funding structures available to the patient, which can affect aspects of rehabilitative care, such as public funding (State or Commonwealth), compensation schemes, private health insurance, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), aged care schemes and self-funding.

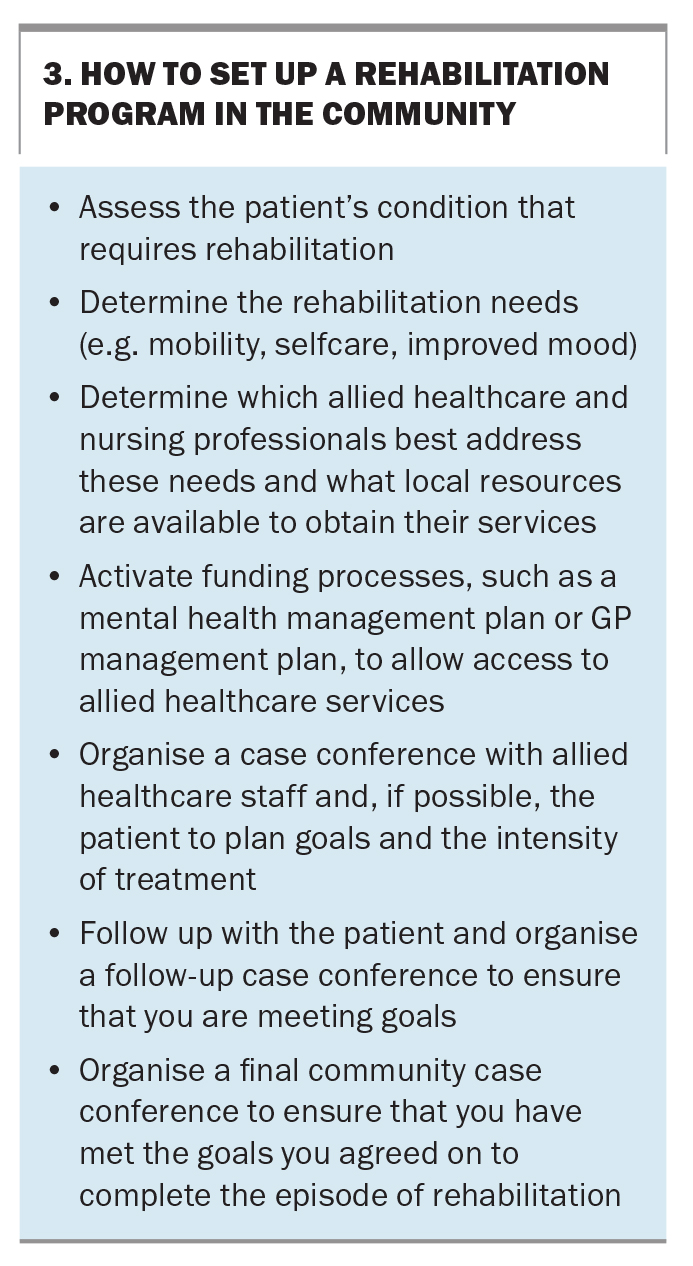

Lastly, understanding the different models of rehabilitative care available to the patient may offer options for rehabilitative care delivery. In some instances, primary care physicians may choose to co-ordinate rehabilitation in the community using options available on the Medicare Benefit Scheme, including a chronic disease management or team care arrangement plan, mental health treatment plan, and multidisciplinary case conferences. Key steps to setting up a rehabilitation program in the community are outlined in Box 3.

Models of rehabilitative care

In the hospital

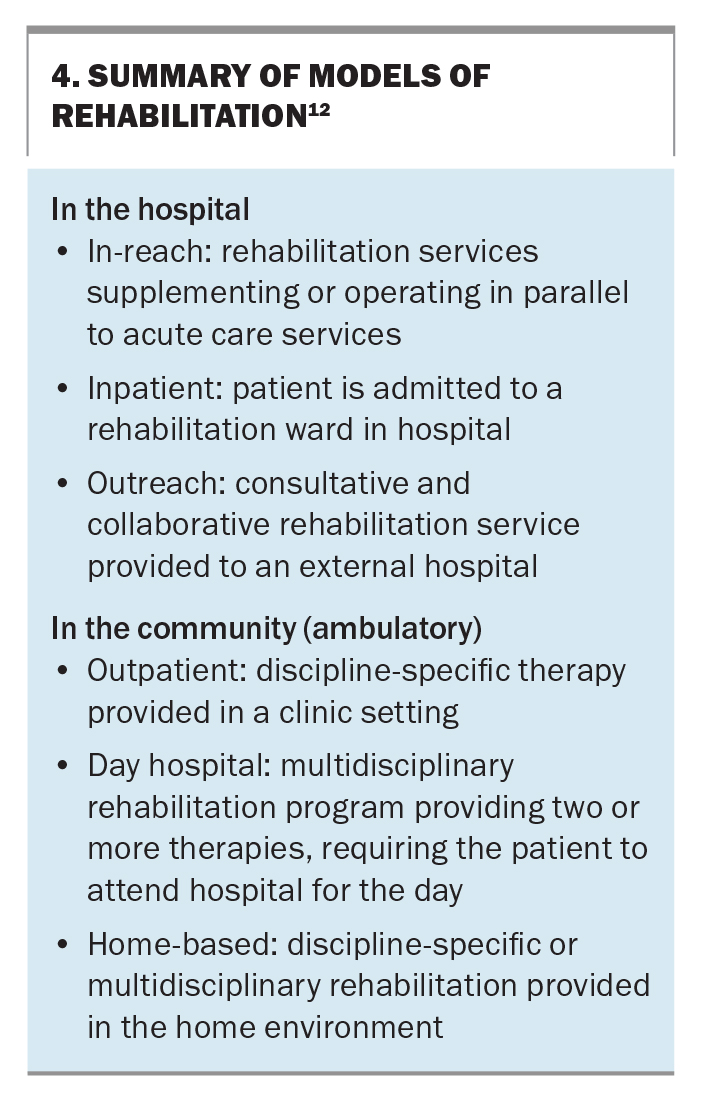

The two broad settings for rehabilitative care are: in the hospital or in the community (Box 4).12 Within the hospital, two service models predominate. The traditional setting involves the person with a disability being an ‘inpatient’ on a rehabilitation ward under the care of a rehabilitation physician.12 Alternatively, ‘in-reach’ rehabilitation can be offered. This is when the patient remains under the care of an acute physician or surgeon, with MRT services implemented in parallel to ongoing acute treatment plans.12 The in-reach model is useful for patients who are keen to participate in a rehabilitation program but transfer to a rehabilitation ward is delayed because of ongoing medical or surgical treatments. A third ‘outreach’ service also exists and is useful when no existing rehabilitation service or rehabilitation physician are available within a hospital. These hospitals may have a consultation service with an external rehabilitation physician working collaboratively.

Who is suitable for inpatient rehabilitation?

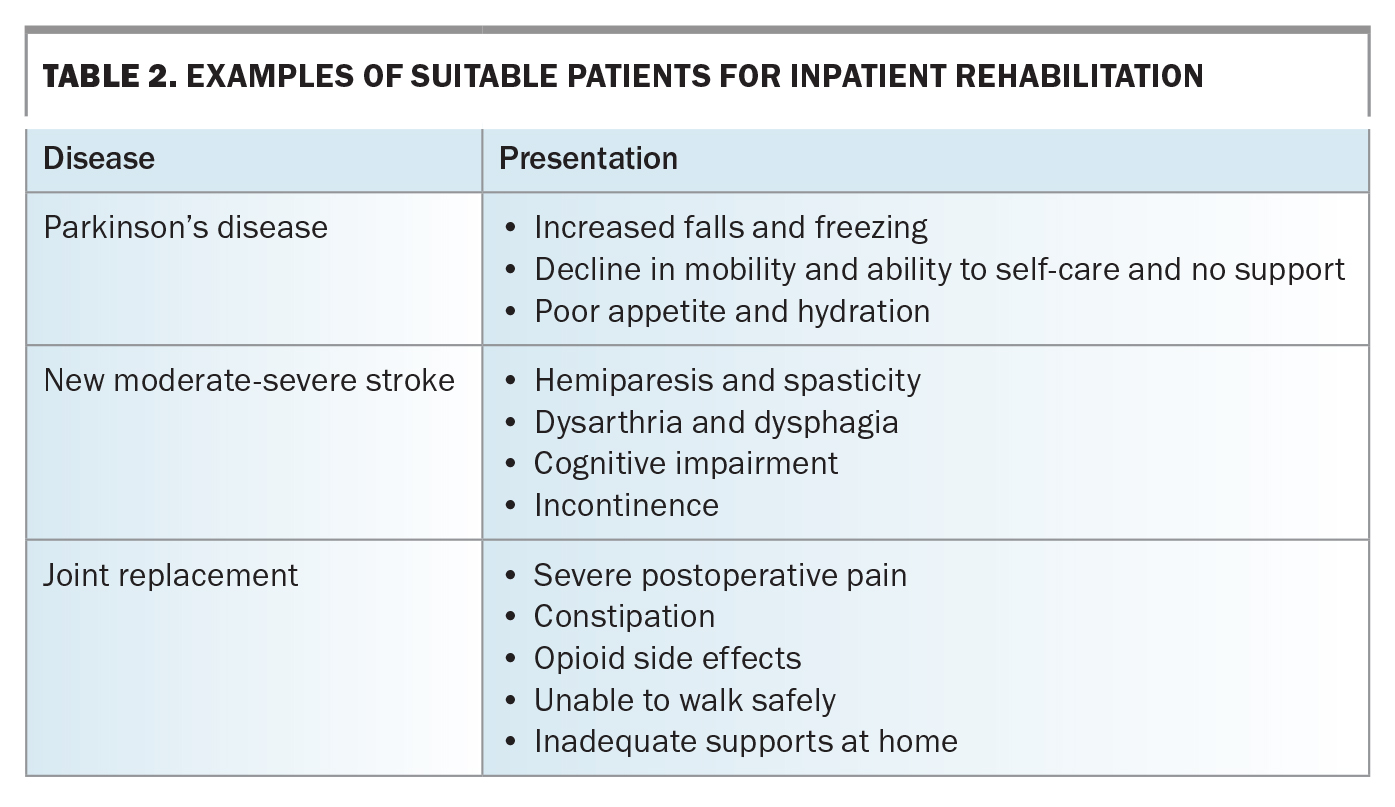

Inpatient rehabilitation is more intensive, usually offering daily therapy. This intensity is more suited to those experiencing recent deterioration of function because of acute illness or injury, which often is the cause of initial hospitalisation, with the overall aim of supporting the patient to return home or back into the community safely.

An alternative pathway to refer patients from the community into an inpatient rehabilitation program also exists and is suitable for those who are deemed to be temporarily unsafe to remain in their dwelling because of functional decline associated with their disability. In these instances, GPs can directly refer the patient to the local public rehabilitation service within a district or, if the patient has appropriate private health cover, a private rehabilitation hospital. Patients most suited for inpatient rehabilitation are outlined in Table 2.

In the community

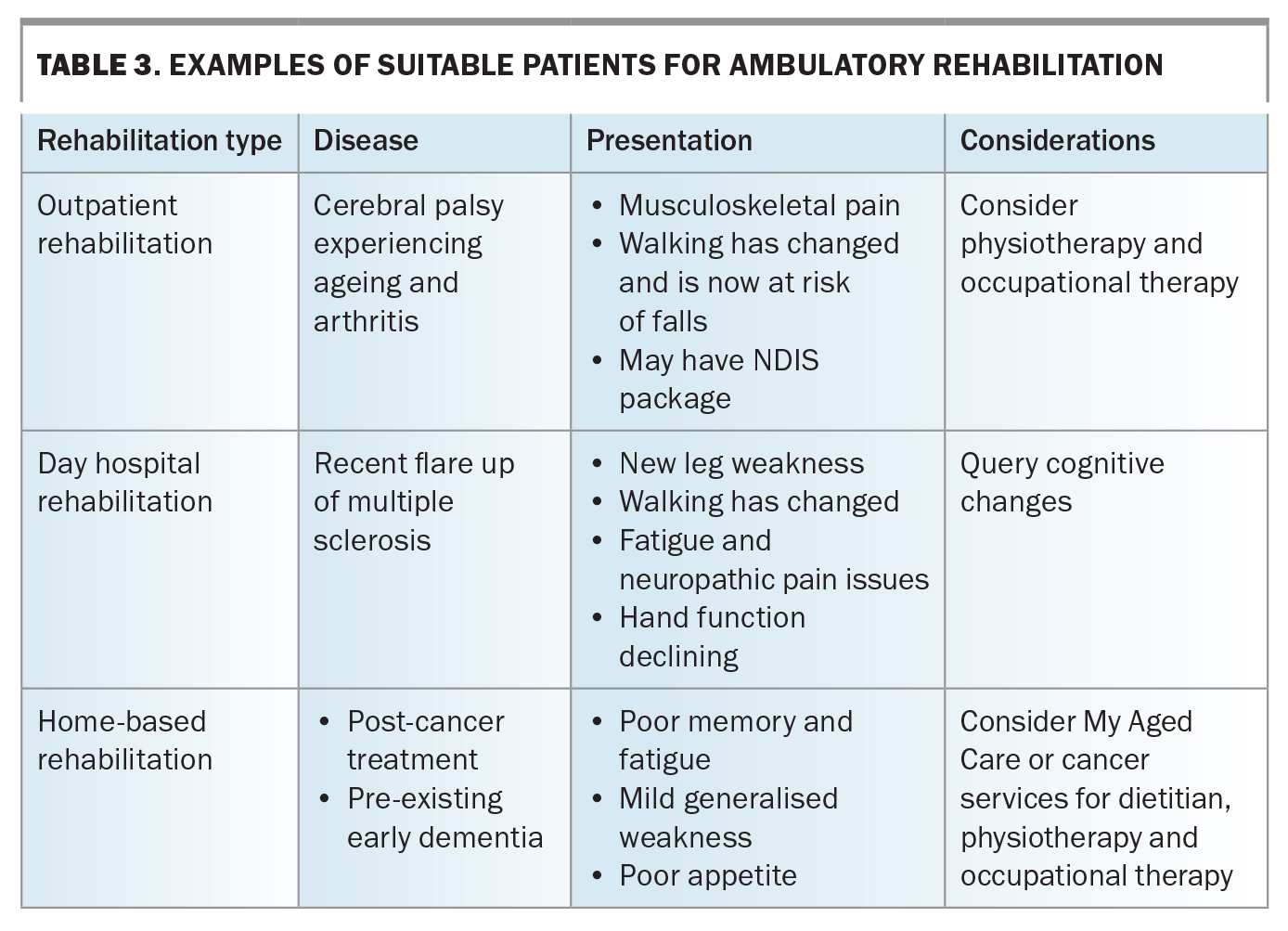

Rehabilitation in the community is called ambulatory rehabilitation. Primary care physicians may directly access or refer patients to ambulatory services. The three predominant ways of delivering ambulatory rehabilitation are through conventional outpatient or clinic services, day hospital, or home-based rehabilitation. Examples of patients suited for ambulatory rehabilitation are given in Table 3.

Outpatient rehabilitation

Outpatient rehabilitation involves the patient attending planned individual clinic appointments with the clinician or therapist.12 The frequency of therapy sessions depends on the patient’s clinical needs. This model of delivery is the lowest intensity of rehabilitation as patients are seen infrequently. It is also often affected by funding models.

Primary care physicians may opt to co-ordinate and manage rehabilitative care using the Medicare-supported Chronic Disease Management, or Team Care Arrangement plan provided the person with a disability requires at least two healthcare services.13 They may also access mental health support via the Mental Health Treatment plan and consider co-ordinating a multidisciplinary case conference with the MRT (summarised above). Other options for rehabilitation include referring the patient to district hospital outpatient rehabilitation services to access state- or federally-funded therapy. Patients who are NDIS participants may access funding for individual therapies via their NDIS plan, and those under compensation schemes require approval to be sought through their insurer. If applicable, patients may also access separate therapies through their private health insurance. Alternatively, individuals may decide to self-fund therapy sessions. Outpatient rehabilitation is most suited to those with a chronic disability who are experiencing new decline but remain safe to reside in the community.

Day hospital rehabilitation

Day hospital rehabilitation is a service model in which patients continue to reside at home, but attend a rehabilitation hospital, where they are day-admitted to undergo multiple therapy sessions as an inpatient under the care of a rehabilitation physician.12 This structure is useful for those requiring two or more different discipline of therapies, who have the capacity to participate in more than one therapy in a single day and may attend up to twice a week. Due to its funding structure, this service model is predominantly available in the private health sector, at private rehabilitation hospitals. Day hospital rehabilitation is most suited to those requiring a short but intensive burst of therapy.

Home-based rehabilitation

The term ‘home-based’ rehabilitation is as it sounds – when rehabilitation therapies are delivered within the patient’s home.12 This structure is particularly useful when patients are unable to safely leave their home to travel to hospital or clinics, or in instances where task-specific therapy can be more effectively performed by patients in their home environment. Home-based rehabilitation should also be considered for patients with cognitive or memory impairments, where task-repetition in a familiar environment can help with establishing routine.14 The intensity or frequency of home-based rehabilitation therapies will depend on the funding source of the service.

People over the age of 65 years may access individual home-based therapies through the Commonwealth-funded My Aged Care (MAC) services, after undergoing a community aged care assessment. MAC offers short-term restorative care, which includes care services, nursing, transport and most common therapies.15 MAC also offers transition care for people initially leaving hospital who need short-term services and therapy support for up to 12 weeks; however, this service requires assessment and approval while the patient is still in hospital.16

NDIS participants and compensable patients may also access home-based therapies through their private health insurance provider or NDIS plans; however, the allocated budget and any additional therapist travel costs should be considered. Home-based rehabilitation through these sources is usually not frequent or intensive and may range from weekly to monthly sessions.

Currently, home-based rehabilitation services are limited within the public healthcare system.17 Traditionally, these multidisciplinary services have been available only to those with traumatic brain injuries, or spinal cord injuries. However, there has been a steady trend over the years towards public hospitals establishing more home-based services, such as the Hospital in the Home (HITH) service – which provides medical, nursing and some allied health intervention aimed at supporting earlier hospital discharge. Variations of HITH are available for patients recovering from temporary acute illnesses or chronic palliative illness. Programs are also available in different health districts for specific conditions of concern.

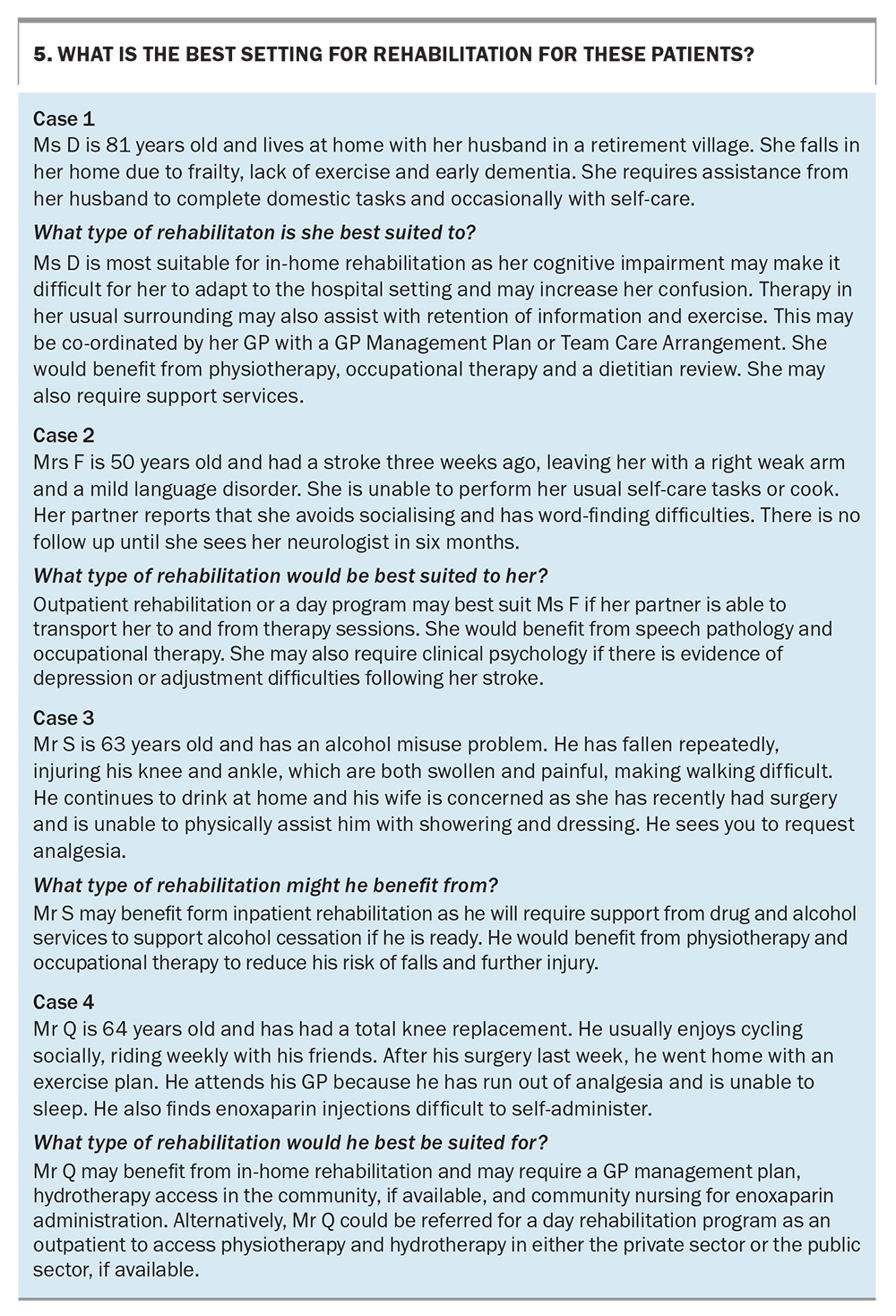

The Rehabilitation in the Home (RITH) program is another version of HITH, as a multidisciplinary home-based rehabilitation model that provides co-ordinated medical, nursing and more substantial allied health support to those with predominantly changed function as a result of illness or injury, who are ready to return home but would benefit from ongoing co-ordinated therapy.17 Patients may be referred to their local home-based services from the hospital, or in the community by primary care physicians and specialists. However, these services currently remain very limited in most health districts. Optimal setting for rehabilitation for patients with differing needs are outlined in a series of short case studies in Box 5.

The future of rehabilitative care

Most research on home-based rehabilitation has only focused on the delivery of single discipline therapy for musculoskeletal disability, such as temporary disability due to a joint replacement. Only two studies compared ambulatory rehabilitation with inpatient rehabilitation for joint replacement, and the measured outcomes and costs did not show one to be superior to another.18,19 Several studies comparing in-home multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs with inpatient rehabilitation for mild to moderate stroke showed comparable outcomes but with varying mortality. No detailed costs-effectiveness studies have been completed.20-24

Multidisciplinary home-based rehabilitation is of great interest to patients with financial concerns about the cost of receiving healthcare, but its detailed study is still lacking at present. Future research should focus on multisite studies comparing multidisciplinary home-based rehabilitation with inpatient rehabilitation for clinical outcomes, cost effectiveness and cost benefit.

With the experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare services have also continued to develop their capacity to deliver virtual and hybrid models of care. This has also been the case in rehabilitation. Further research and service design will continue to support development of virtual and hybrid ambulatory rehabilitation services.25

Conclusion

Rehabilitation should be considered as part of care for people experiencing acute, chronic or permanent disability as a result of illness or injury, to optimise health outcomes, independence and function, reduce burden of care and improve QOL. Ambulatory rehabilitation services are available in several forms, with varying structures, for the primary care physician to access or to refer patients for multidisciplinary rehabilitative care in the community. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Lam is Chair of the Private Practice Special Interest Group, Rehabilitation Medicine Society of Australia and New Zealand (RMSANZ). Professor Faux is a Board Member of the RMSANZ and on the data safety monitoring board for a home-based therapy trial.

References

1. Australian Network on Disability. Disability Statistics. Australian Network on Disability. Sydney; Australian Network on Disability, 2019. Available online at: https://www.and.org.au/pages/disability-statistics.html (accessed March 2023).

2. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: Summary of Findings, 2015. Canberra: ABS, 2015. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/4430.0main+features202015 (accessed March 2023).

3. World Health Organization (WHO). World Report on Disability. Geneva; WHO, 2011. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/sensory-functions-disability-and-rehabilitation/world-report-on-disability (accessed March 2023).

4. Royal Australian College of Physicians (RACP). Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine (AFRM). Sydney; RACP, 2023. Available online at: https://www.racp.edu.au/about/college-structure/australasian-faculty-of-rehabilitation-medicine (accessed March 2023).

5. National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). Australia’s Disability Strategy 2021-2031. NDIS, 2021. Available online at: https://www.ndis.gov.au/understanding/australias-disability-strategy-2021-2031#:~:text=Australia’s%20Disability%20Strategy%202021%2D2031%20outlines%20a%20vision%20for%20a,inclusion%20of%20people%20with%20disability (accessed March 2023).

6. World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva; WHO, 2001. Available online at: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed March 2023).

7. World Health Organization (WHO). International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva; WHO, 2001. Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42407/9241545429.pdf;jsessionid= 23531FA63C24A7F2808405BBB0395A5B?sequence=1 (accessed March 2023).

8. Australasian Rehabilitation Outcomes Centre (AROC). State of the Nations (SoN). Episodes by Impairment – 2022. Wollongong; AROC, 2022. Available online at: https://aos.aroc.uow.edu.au/AOS/DataVis/ViewDataVis/18?token=public (accessed March 2023).

9. Australasian Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine (AFRM). Standards for the provision of rehabilitation medicine services in the ambulatory setting 2014. Sydney; AFRM, 2014. Available online at: https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/advocacy-library/ambulatory-standards.pdf (accessed March 2023).

10. Queensland Health. Rehabilitation Services. CSCF v3.2. Brisbane; Queensland Government. Available online at: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0024/444363/cscf-rehabilitation.pdf (accessed March 2023).

11. World Health Organization (WHO). Chapter 4: Rehabilitation. In: World Report on Disability 2011. Geneva; WHO, 2011. p. 97.

12. Agency For Clinical Innovation (ACI). Principles to Support Rehabilitation Care. ACI Rehabilitation Network. Sydney; NSW Health, 2019.

13. The Department of Health and Aged Care. Chronic Disease Management – GP services. Canberrs; Department of Health and Aged Care, 2014. Available online at: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mbsprimarycare-chronicdiseasemanagement (accesses March 2023).

14. Zasler ND, Katz DI, Zafonte RD (eds). Brain Injury Medicine: Principles and Practice. Springer Publishing; New York, 2007.

15. MyAgedCare (MAC). Short-term restorative care. Canberra; Australian Government. Available online at: https://www.myagedcare.gov.au/short-term-care/short-term-restorative-care (accesses March 2023).

16. MyAgedCare (MAC). Transition care. Canberra; Australian Government. Available online at: https://www.myagedcare.gov.au/short-term-care/transition-care (accesses March 2023).

17. NSW Health. Adult and Paediatric Hospital in the Home Guidelines. Sydney; NSW Government, 2018. Available online at: https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/Pages/doc.aspx?dn=GL2018_020 (accesses March 2023).

18. Sindhupakorn B, Numpaisal PO, Thienpratharn S, Jomkoh D. A home visit program versus a non-home visit program in total knee replacement patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Surg Res 2019; 14: 405.

19. Kauppila AM, Kyllonen E, Ohtonen P, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation after primary total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled study of its effects on functional capacity and quality of life. Clin Rehabil 2010; 24: 398-411.

20. Anderson C, Mhurchu CN, Rubenach S, Clark M, Spencer C, Winsor A. Home or hospital for stroke Rehabilitation? Results of a randomized controlled trial : II: cost minimization analysis at 6 months. Stroke 2000; 31: 1032-1037.

21. Kalra L, Evans A, Perez I, Knapp M, Donaldson N, Swift CG. Alternative strategies for stroke care: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000; 356: 894-899.

22. Kalra L, Evans A, Perez I, Knapp M, Swift C, Donaldson N. A randomised controlled comparison of alternative strategies in stroke care. Health Technol Assess 2005; 9: iii-iv, 1-79.

23. Ozdemir F, Birtane M, Tabatabaei R, Kokino S, Ekuklu G. Comparing stroke rehabilitation outcomes between acute inpatient and nonintense home settings. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82: 1375-1379.

24. Ricauda NA, Bo M, Molaschi M, et al. Home hospitalization service for acute uncomplicated first ischemic stroke in elderly patients: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52: 278-283.

25. Qiu Q, Cronce A, Patel J, et al. Development of the home based virtual rehabilitation system (HoVRS) to remotely deliver an intense and customized upper extremity training (2020). J NeuroEngineering Rehabil 2020; 17: 155.