What happens in a public health acute stroke unit? The role of allied health

Clinical guidelines recommend that all stroke survivors should be treated and managed in a stroke unit by an interdisciplinary team who have expertise in stroke and rehabilitation. Allied health professionals are an integral part of this team. The model described in this article refers to usual practice in a public hospital stroke unit.

- Physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, social workers, psychologists, dietitians and podiatrists are involved in providing evidence-based treatment and management for stroke survivors in a public acute stroke unit.

- Allied health professional involvement varies and is individualised to the healthcare needs of each stroke survivor.

- Allied health professionals have a role in assessment, treatment, management and planning in collaboration with stroke survivors and/or their families, and the stroke medical and nursing teams.

- A stroke survivor’s rehabilitation journey often commences in the acute stroke care unit.

- This article provides insights into the complexities of the early rehabilitation process that may be especially relevant for aspiring rehabilitation physicians and medical students.

Stroke is the second leading cause of death and third leading cause of disability worldwide and results in significant economic and societal costs.1 Much of the focus in stroke management is on thrombectomy (mechanical clot extraction) and the use of clot-busting drugs for an acute ischaemic stroke, with ambulance services implementing procedures for the rapid transfer of people with a suspected stroke to reperfusion and stroke unit-capable centres.2 In addition to time-critical management, people who have had a stroke benefit from care in geographically located stroke units, with clinical trials showing reductions in disability, length of stay and mortality.3 In 2021, 93 hospitals in Australia had a stroke unit providing specialised stroke care.4 A list of hospitals providing reperfusion therapy or stroke unit care is available from the Stroke Foundation’s website (https://strokefoundation.org.au/about-stroke/learn/treatment-for-stroke/stroke-care-units#units). Eighty percent of people presenting with an acute stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) are treated in the public healthcare system.5

One of the characteristics of a highly effective stroke unit is an interdisciplinary team, consisting of medical, nursing and allied health professionals.4 Among allied health professionals, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech pathologists, social workers, psychologists and dietitians are the minimum needed to provide comprehensive stroke care.6 This article describes the health care provided by allied health professionals in a metropolitan comprehensive stroke centre.7 Physiotherapists and occupational therapists assess all stroke survivors, whereas all other allied health professionals assess stroke survivors via referral when clinically indicated. This article aims to provide GPs with a more in-depth understanding of the allied health professional’s role in a stroke survivor’s journey through a public health acute stroke unit.

Comprehensive stroke centre: the pathway from emergency care to the acute stroke unit

Early medical management

Medical management of an acute stroke or TIA in a comprehensive stroke centre includes evaluation by the acute stroke code team in the emergency department, who are available 24/7. This team identifies patients with clots requiring reperfusion therapy using multimodality brain scans (including sequences for blood flow mapping, CT perfusion, intracranial and extracranial blood vessel imaging or CT angiography).8 Patients are admitted to the stroke unit based on clinical need. For example, patients with TIA can be safely discharged with structured outpatient TIA management after they have received antithrombotic medications and appropriate investigations to evaluate the TIA mechanism.8 TIA health pathways are available from public tertiary teaching hospitals.

Swallowing safety

A swallowing screen is conducted by a trained nurse or allied health assistant under the delegation of a speech pathologist, typically within four hours of hospital arrival.9,10 Among stroke survivors with severe deficits, impaired swallowing (dysphagia) is associated with complications, such as aspiration pneumonia, choking, malnutrition and dehydration.11 Screening is performed before any oral food, fluid or medication is given.6,12 If dysphagia is detected, a referral to a speech pathologist is made for further assessment and management. Speech pathology services can operate up to seven days per week in the emergency department. This may vary between organisations. A stroke survivor who requires a speech pathology review to facilitate discharge from the emergency department will typically be seen within a set time frame from referral during onsite serviced hours.

Early mobility and assessment of physical function

Physiotherapy services can also operate up to seven days per week in the emergency department. Following reperfusion therapy, stroke survivors usually rest in bed for 24 hours. However, if their stroke is conservatively managed, there are usually no mobility limitations. At this time, a physiotherapist will assess the stroke survivor’s mobility and functional capacity. The first contact focuses on evaluating the stroke survivor’s physical capability and independence (through tests of sitting, walking, balance and arm function) and guiding discharge and rehabilitation planning. If a stroke survivor passes the swallowing screen and has appropriate physical capacity to be discharged home directly from the emergency department, the physiotherapist may request the involvement of a care co-ordinator. Some comprehensive stroke centres have care co-ordinators who are allied health professionals delivering a transdisciplinary model of care, typically only for people following TIA. They complete further functional and social assessments to determine safety for the patient’s direct discharge home.

Transfer from the emergency department to the acute stroke unit

In collaboration with stroke survivors and/or their family, the emergency department healthcare team determines the clinical need for admission to the acute stroke unit. This is indicated when stroke survivors require further medical care, present with significant impairments or do not have the appropriate support to be discharged directly home. The time it takes to be transferred to the acute stroke unit varies depending on bed availability. If there is no bed availability on the stroke unit, stroke survivors will be provided a bed in another ward, as an ‘outlier patient’. Despite the location, allied health professionals from the stroke unit will assess and provide treatment for all stroke survivors. Stroke survivors on outlier wards are prioritised for transfer to the stroke unit as soon as a bed is available.

Acute stroke unit: allied healthcare on the ward

Person-centred care

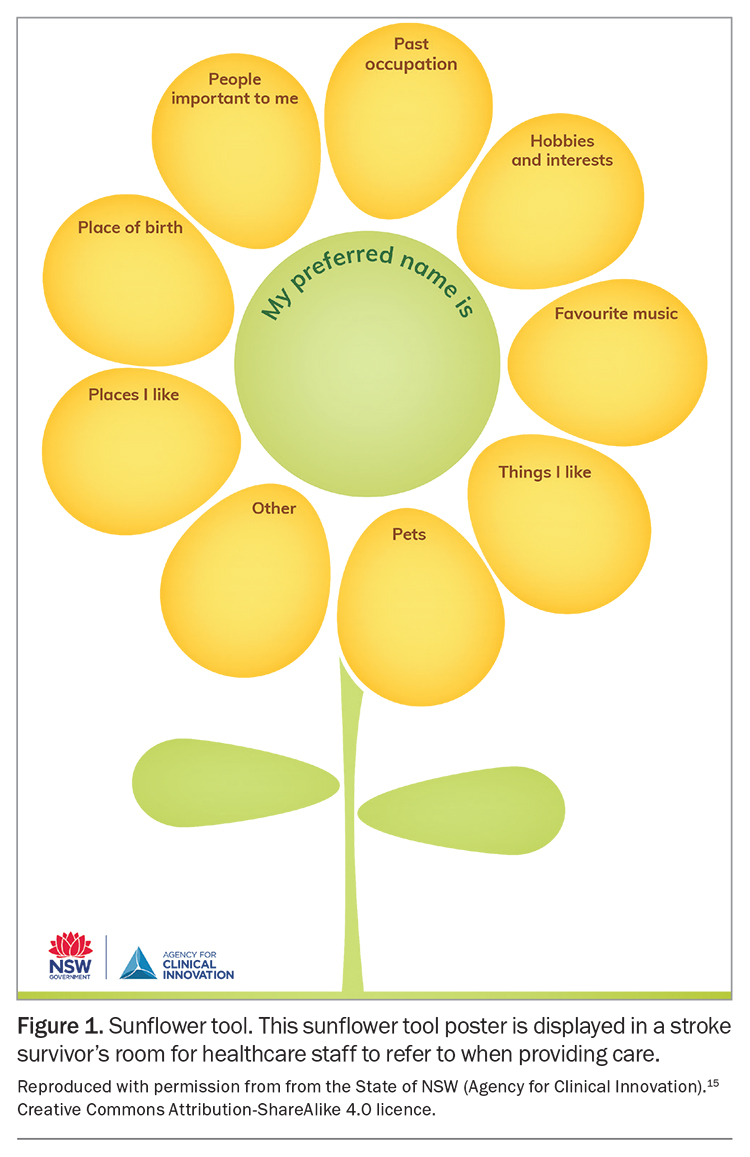

Activity within an acute stroke unit is individualised and driven by stroke survivors through individualised goal setting and treatment planning.13 Allied health professionals collaborate with stroke survivors and/or their families to set short- and medium-term SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Time-bound) goals and plan treatment focused on achieving the short-term goals during the acute stroke unit admission.14 Goal setting is an iterative process between stroke survivors and allied health professionals, which can be modified as a stroke survivor’s deficits, abilities and wishes change. The sunflower tool is available to help with getting to know stroke survivors and their individual preferences (Figure 1).15 It is often used by occupational therapists and speech pathologists with stroke survivors and their families or carers.

Stroke education

Stroke survivors and their families receive the Stroke Foundation’s My Stroke Journey book, which provides information on available support, recovery and reducing the risk of future strokes.16 The book is available in several languages, including English and Italian, with translations to other languages currently under development. Members of the interdisciplinary team share the responsibility of providing this book to each stroke survivor and their families. Education is delivered using an interpreter or recommended communication strategies, if required.

Acute stroke unit: allied health assessment

Assessment of physical function

Once admitted to the stroke unit, a physiotherapist and occupational therapist expand on the initial emergency department assessment of a stroke survivor’s physical function, if seen. The assessment considers the impairment (body structure and function), activity and participation levels, as well as environmental and personal factors using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.17

In addition to assessing a stroke survivor’s ability to sit up in bed, stand, walk and participate in activities of daily living, a physiotherapist and occupational therapist will examine the impairments caused by the stroke. This includes, but is not limited to, changes in strength, sensation, co-ordination, proprioception, joint range of motion and muscle overactivity (spasticity, hypertonicity and dystonia). This examination identifies the factors contributing to a stroke survivor’s reduced physical function and facilitates a targeted selection of early rehabilitation treatment options. A complete examination may occur across multiple sessions and days (typically one to three sessions). Depending on the outcomes, a second, or even third, therapist may be required to assist stroke survivors to transfer or walk with the physiotherapist to provide ‘early mobility’.18

The occupational therapist assesses a stroke survivor’s ability to participate in everyday occupations, such as dressing, toileting or grooming. Specific physical aspects, such as arm and hand movements, in addition to impacts on cognition, vision and perception, may affect function in daily activities. Occupational therapists also assess the risk of pressure injury. This comprehensive assessment can be performed in a single session if stroke survivors present with mild deficits, or over multiple sessions during their admission.

Assessment of cognition

Cognitive impairment is present in about 32% of acute stroke survivors and may include impairments in attention, memory, problem solving, reasoning and executive functioning.4,19 Owing to the close interplay of cognition and communication abilities, occupational therapists and speech pathologists collaborate to identify a stroke survivor’s cognitive communication profile and select the most appropriate standardised assessment. An occupation- based assessment of cognition typically follows (e.g. assessing the impact of cognitive impairment during the preparation of a hot drink). In instances where establishment of poststroke cognitive function is complex, such as difficulty differentiating premorbid cognition from current or high-functioning individuals whereby standard cognitive screening measures are less sensitive, referral to a neuropsychologist is initiated.

Assessment of vision and perception

An estimated 65% of stroke survivors will experience changes in vision, and 30% will experience spatial neglect.20,21 Occupational therapists assess stroke survivors for visual or perceptual changes using a combination of observation tasks (e.g. reading, scanning the environment) and standardised and nonstandardised assessment tools.

Assessment of communication

In Australia, over half of all people admitted with a stroke exhibit communication deficits.4 When a stroke survivor’s communication is impaired, a referral is made by a member of the stroke unit team to a speech pathologist for assessment and management. Speech pathologists assess for slurred speech (dysarthria); poorly co-ordinated speech (apraxia); poor voice quality and volume (dysphonia); and difficulty with talking, reading, writing and understanding (aphasia). A communication assessment may be completed over multiple sessions, pending the severity of communication impairment and a stroke survivor’s ability to participate in speech pathology sessions, alertness and medical status.

Assessment of swallowing

In the acute stroke unit, a bedside swallowing assessment includes a cranial nerve assessment to test strength, range of movement and speed of swallowing muscles. A range of modified diet and fluid textures are then trialled, with the aim to commence the most appropriate oral intake. If more objective information is required, a speech pathologist, in conjunction with the medical team, orders, performs and interprets one of two instrumental swallowing assessments: swallowing x-ray ‘videofluoroscopy’ or camera scope ‘fibreoptic endoscopy’.

Assessment of nutrition

All stroke survivors admitted to the acute stroke unit are screened for malnutrition by nursing staff on admission and weekly thereafter. Patients at risk of malnutrition are referred to a dietitian for a comprehensive nutrition assessment and an individualised management plan to treat, prevent and manage malnutrition.

Acute stroke unit: allied health management and early rehabilitation

Early management plans

Early management plans are designed in collaboration with stroke survivors and allied health professionals to work towards identified goals and minimise or prevent secondary complications. These are typically implemented within the first one to five sessions and can include, but are not limited to:

- initiating goal setting discussions with stroke survivors and/or their families or carers

- discussing discharge planning options

- providing transfer and mobility recommendations including the minimisation of falls, appropriate seating (tilt-in-space wheelchairs) and pressure-relieving cushions

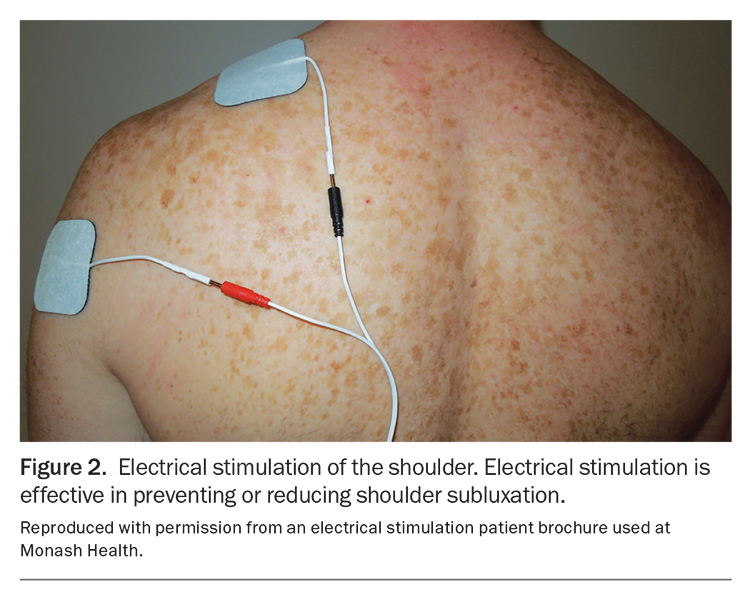

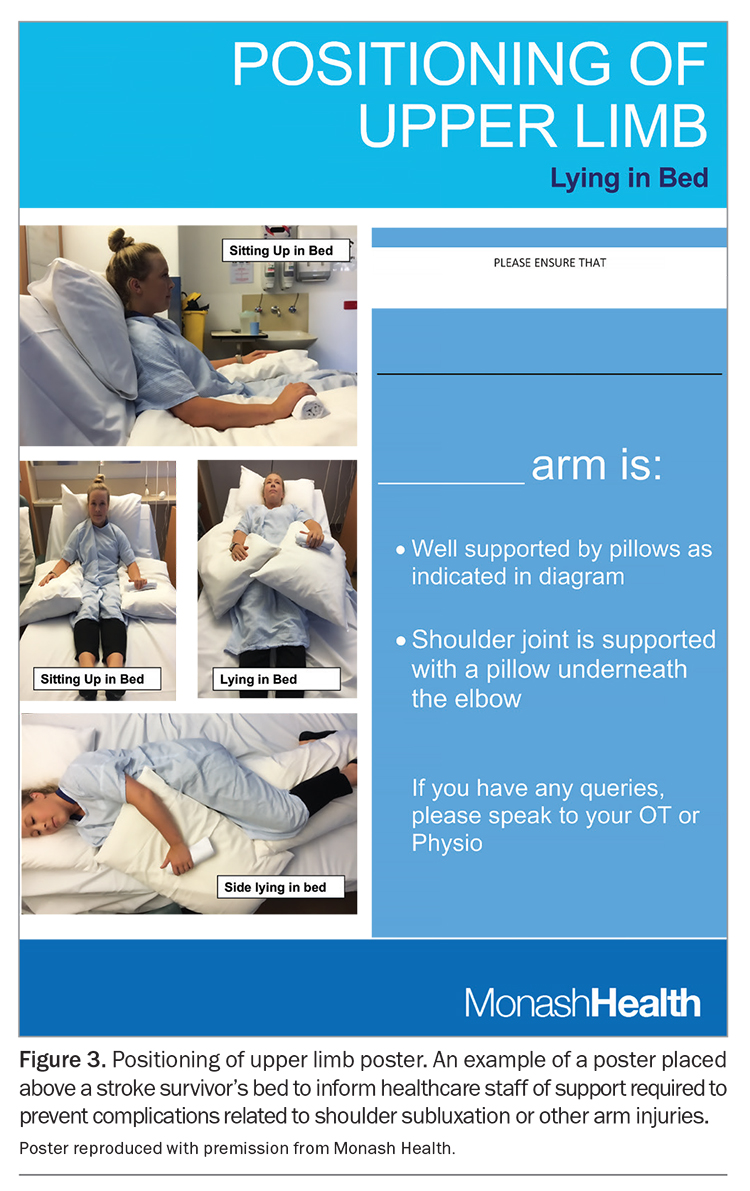

- managing the hemiplegic upper limb using approaches, such as electrical stimulation (Figure 2), shoulder strapping, positioning aids and collar and cuff slings;22 positioning posters are often placed above a stroke survivor’s bed (Figure 3)

- implementing strategies to manage cognitive, perceptual or vision deficits

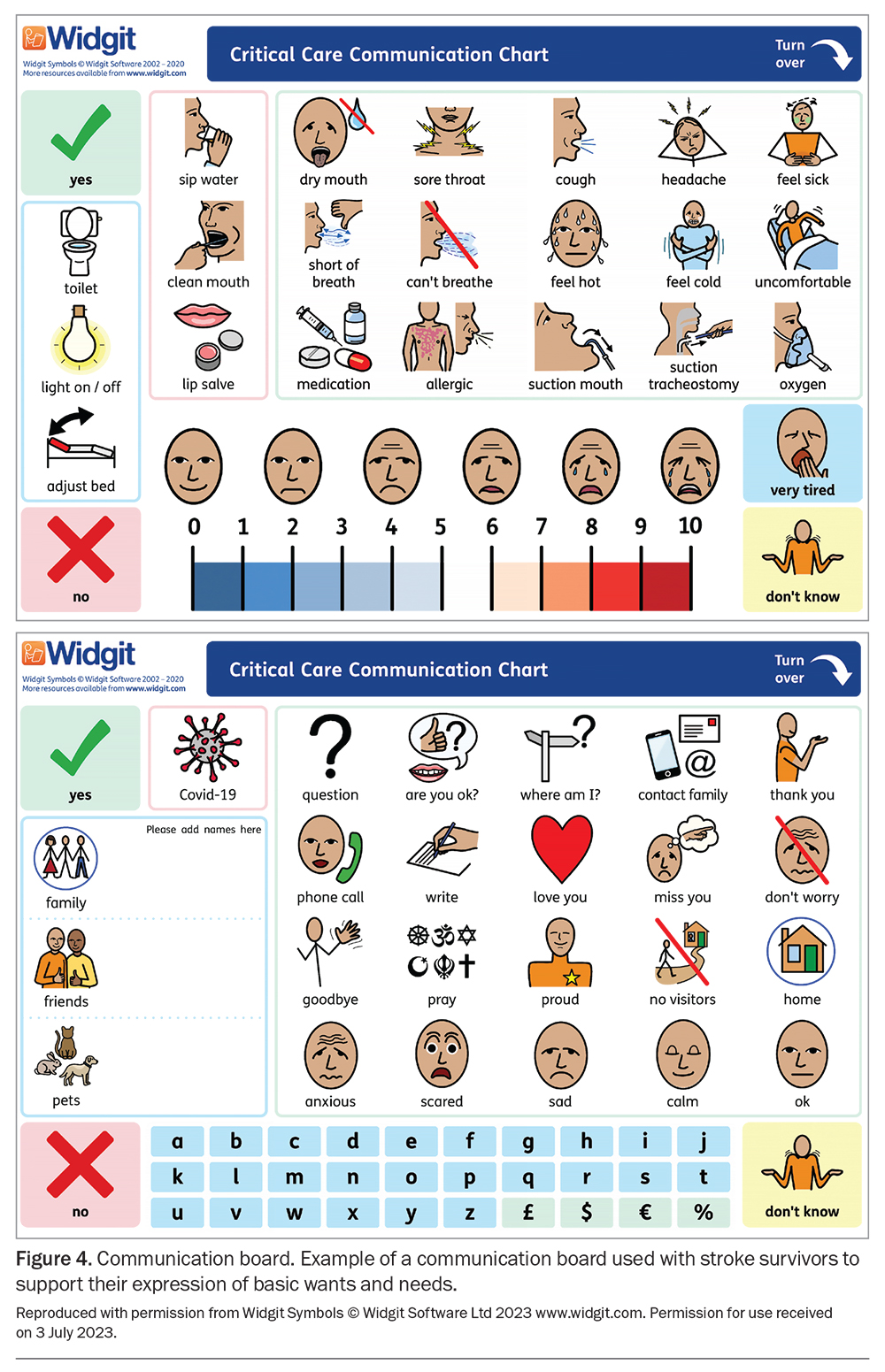

- supporting the communication of basic needs with tools and strategies with posters and picture or alphabet boards

- implementing appropriate diet, texture and fluid consistency with safe swallowing strategies

- implementing individualised nutrition optimisation strategies for patients at risk of malnutrition, including a high-energy, high-protein, texture-modified diet and supplements or enteral nutrition; enteral nutrition can be administered short term via a nasogastric tube or longer term via a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube to ensure the patient has sufficient sustenance to support recovery

- prescribing independent or family or carer supported exercise programs.

Key areas of care

Allied health professionals provide clinical care across a wide range of areas. The following key areas highlight the unique and diverse skills required by allied health professionals working with stroke survivors in a stroke unit.

Tracheostomy care

Some stroke survivors require mechanical ventilation if the stroke impacts their ability to breathe independently and may require a tracheostomy.23 Speech pathologists and physiotherapists work collaboratively to assess and wean stroke survivors from the tracheostomy. Dietitians have expertise in nutritional intake and delivery routes.24 Speech pathologists assess oral secretion management, swallowing effectiveness (airway protection) and voice (airway patency). They support stroke survivors in their ability to communicate by determining whether a speaking valve is suitable or alternative options, such as communication boards (Figure 4) or gesturing, are appropriate.25 Physiotherapists are responsible for monitoring the respiratory status and airway clearance (suctioning and breathing exercises). Together, they provide education and are skilled in recognising and managing tracheostomy emergencies, such as respiratory deterioration. In addition, a specialist-altered airway consultative team consisting of an intensive care unit consultant, critical care nurse, speech pathologist and physiotherapist provides specialist support to the ward team for management and weaning from tracheostomy.

Early rehabilitation within the stroke unit

There are strong recommendations that mobilisation (out-of-bed activity) should commence within 48 hours of a stroke unless contraindicated.6 However, A Very Early Rehabilitation Trial after stroke (AVERT) showed that there may be a greater risk of harm and less favourable outcomes from intensive, very early, out-of-bed activity within 24 hours of stroke onset.26 As such, early rehabilitation starts in the acute stroke unit within 24 to 48 hours of admission or medical intervention and may be delayed if a stroke survivor is medically unstable. Most treatment sessions occur at a stroke survivor’s bedside. Sessions may also occur in a centralised gymnasium space (Figure 5). The gymnasium space contains dedicated equipment including an exercise plinth, supportive standing equipment and upper limb activity resources for stroke survivors to practice activities and participate in exercise. The treatment location is influenced by medical stability, number of medical lines and ability to move stroke survivors from their bed to the gymnasium space.

Physiotherapists and occupational therapists can provide a variety of rehabilitation options, including task-specific training or hands-on therapy, to facilitate normal movement patterns, strength and balance retraining, modified constraint-induced movement therapy and functional electrical stimulation.27,28 Early task-specific rehabilitation interventions lead to neural changes, known as neuroplasticity, the regeneration and formation of new neuronal connections, contributing to the recovery of function.26,29 The window of opportunity for recovery is time-limited for neuroplasticity following stroke and can be further augmented by rehabilitation.29 Stroke survivors can also participate in exercise group therapies, such as arm exercise groups. These groups may be run by physiotherapists, occupational therapists or allied health assistants.

Speech pathologists provide both compensatory and rehabilitative therapeutic strategies for managing and treating dysphagia. Compensatory strategies involve altering how swallowing occurs through different head and neck positions, modifying food and drink delivery (smaller amounts) and sensory stimulation (to elicit swallowing). Rehabilitation strengthens the muscles of the oral cavity and throat. Communication therapy may involve the use of technology, such as language therapy applications on an iPad (Figure 6) or photographs, to elicit target words.

A more comprehensive summary of the evidence for specific interventions for stroke management can be found in chapters 5 and 6 of the Australian and New Zealand Living Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management by the Stroke Foundation.6

Muscle overactivity, casting and braces

Physiotherapists and occupational therapists have a shared role in managing and treating the upper limb, whereas physiotherapists typically work alone in providing similar treatment interventions specific to the lower limb. Management of upper and lower limb muscle overactivity (spasticity, hypertonia and dystonia) is common. In the acute stroke unit, various strategies, such as active motor retraining, positioning and, where indicated, serial casting (successive casts providing prolonged stretch with a graduated increase in the range of movement), are used to maintain optimal positioning of a stroke survivor’s arms, hands, legs and feet.30 If indicated, the physiotherapist or occupational therapist will recommend appropriate pharmacological management of muscle overactivity, including botulinum toxin injections, in collaboration with the stroke medical team.

Psychology and wellbeing

Stroke survivors and families requiring emotional support will often be referred to social work. Social workers complete a full psychosocial assessment to understand the current situation and identify psychosocial issues. Social workers typically provide counselling and emotional support for stroke survivors and their families or carers, as well as support with adjusting to the illness and decision-making.

Some stroke survivors experience emotional or behavioural disturbances, such as those caused by post-stroke anger proneness.31 This may result in escalated behaviours that impact the wellbeing or physical safety of a stroke survivor or others. This is most common in people who have had a large stroke, have risk factors that may predispose them to delirium or have had a stroke in a particular area of the brain that affects behaviour.32 When escalated behaviours are identified, occupational therapists and nursing staff identify behavioural triggers and de-escalation strategies to develop an individualised behaviour management plan. If required, referral to a neuropsychologist may be indicated for further specialist assessment.

Palliative care

The mortality rate of stroke is about 24 to 25 per 100,000 population.33 If the patient or patient's family, or both, decide to receive palliative care, a social worker will provide ongoing emotional support and counselling. At the end of life, a referral to spiritual care is made to organise the appropriate denominational minister and pastoral care, if the family and/or patient wish to receive this support. Social work, occupational therapists and physiotherapists provide information to the family regarding support, carer training and equipment if the family choose to take the patient home.

Teamwork to enhance healthcare

Stroke survivor activity and participation restrictions, progress and discharge plans are discussed in a daily ‘patient handover’ meeting attended by allied health professionals and medical and nursing teams. This meeting assists with stroke survivor care and ‘patient flow’ through the public hospital system. A weekly interdisciplinary stroke meeting is led by the Aged and Rehabilitation Access Service physician and discusses stroke survivors with complex needs and facilitates the timely transfer of patients to inpatient rehabilitation.

Allied health assistants are an integral part of the allied health team, increasing the intensity of therapy provided. Allied health assistants support all allied health disciplines and are delegated specific rehabilitation tasks. Other allied health professionals, not described above, may also provide healthcare on referral if indicated. For example, a podiatrist may provide wound management, neurovascular assessment of the legs and feet or footwear education.

Discharge planning within the stroke unit

The discharge destination from the acute stroke unit is a decision made collaboratively with stroke survivors, their families or carers and the interdisciplinary team. There are typically three options after an acute stroke unit admission: discharge home with community rehabilitation, with support if required; transfer to inpatient rehabilitation; and discharge to supported accommodation.

Stroke survivors can be discharged home if they are able to manage their daily occupations independently, or with support from families or carers. Throughout a stroke survivor’s acute admission, allied health professionals gather a detailed collateral history of premorbid mobility, occupational performance, the home environment and available support. If additional support is required on discharge, social workers can organise additional formal services and equipment can be provided by occupational therapists. Allied health professionals organise community rehabilitation if stroke survivors have ongoing therapy goals. Education and training to enable families or carers to support stroke survivors safely at home are provided. These may include training for walking and transfers; dressing; toileting; medications; pressure care; and the management of cognitive, communication and nutritional requirements.

If a stroke survivor requires greater care than that available at home and has rehabilitation goals, inpatient rehabilitation is an appropriate option. If a stroke survivor has care needs that cannot be met at home and will not benefit from inpatient rehabilitation, alternative accommodation, such as a residential aged care facility or supported disability accommodation, will be arranged. The social worker facilitates a referral to Aged Care Assessment Services for residential aged care or commences National Disability Insurance Scheme paperwork. Allied health professionals complete detailed discharge summaries and provide verbal handover when discharging patients from the acute stroke unit to inpatient or community rehabilitation or supported accommodation. This supports the care of stroke survivors, minimises clinical risks and improves stroke survivor transition.34

Conclusion

Allied health professionals are an integral part of the health care provided in an acute stroke unit in the public healthcare setting. Stroke survivors are diverse in presentation and, therefore, allied health professionals working in an acute stroke unit require the depth and breadth of skills to optimally assess, treat, manage and facilitate discharge planning for each stroke survivor based on their deficits, abilities and goals. MT

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following allied health professionals from Monash Health for their support and review of this manuscript: Samantha Bradley, Ellen Goh, Sarah Brown, Michelle Kaminski, Michael Splawa-Neyman, Danielle Schubiger, Abby Foster and Niloufar Kirkwood.

COMPETING INTERESTS: Ms Blanc, Ms Garner, Ms Legro, Dr Milne, Ms Morris and Ms Ross: None. Ms Scroggie and Associate Professor Singhal are members of the Cardiovascular Learning Health Network Advisory Group at Safer Care Victoria. Professor Phan has received support from Bayer, Pfizer, BMS Medical and Boehringer Ingelheim.

References

1. GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol 2021; 20: 795-820.

2. Safer Care Victoria. Endovascular clot retrieval for acute stroke: statewide service protocol for Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Government; 2018. Available online at: https://www.safercare.vic.gov.au/clinical-guidance/stroke-clinical-network/endovascular-clot-retrieval-protocol (accessed July 2023).

3. Langhorne P, Ramachandra S, Stroke Unit Trialists’ Collaboration. Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke: network meta-analysis. Stroke 2020; 4: CD000197.

4. Stroke Foundation. National Stroke Audit: Acute Services Report 2021. Melbourne: Stroke Foundation; 2021. Available online at: https://informme.org.au/stroke-data/acute-audits (accessed July 2023).

5. Victorian Government. Stroke care strategy for Victoria. Melbourne: Victorian Government Department of Human Services; 2007. Available online at: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/publications/stroke-care-strategy-for-victoria (accessed July 2023).

6. Stroke Foundation. Living Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management. Melbourne: Stroke Foundation; 2023. Available online at: https://informme.org.au/guidelines/living-clinical-guidelines-for-stroke-management (accessed July 2023).

7. Stroke Foundation. National Rehabilitation Stroke Services Framework 2022. Melbourne: Stroke Foundation, 2022. Available online at: https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-health-professionals/audits (accessed July 2023).

8. Clissold B, Phan TG, Ly J, Singhal S, Srikanth V, Ma H. Current aspects of TIA management. J Clin Neurosci 2020; 72: 20-25.

9. Poorjavad M, Jalaie S. Systemic review on highly qualified screening tests for swallowing disorders following stroke: Validity and reliability issues. J Res Med Sci 2014; 19: 776-785.

10. Benfield JK, Everton LF, Bath PM, England TJ. Accuracy and clinical utility of comprehensive dysphagia screening assessments in acute stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs 2020; 29: 1527-1538.

11. Gonzalez-Fernandez M, Ottenstein L, Atanelov L, Christian AB. Dysphagia after stroke: an overview. Curr Phys Med Rehabil Rep 2013; 1: 187-196.

12. Bray BD, Smith CJ, Cloud GC, et al. The association between delays in screening for and assessing dysphagia after acute stroke, and the risk of stroke-associated pneumonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2017; 88: 25-30.

13. Kang E, Kim MY, Lipsey KL, Foster ER. Person-centered goal setting: a systematic review of intervention components and level of active engagement in rehabilitation goal-setting interventions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2022; 103: 121-130e3.

14. Sugavanam T, Mead G, Bulley C, Donaghy M, van Wijck F. The effects and experiences of goal setting in stroke rehabilitation - a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil 2013; 35: 177-190.

15. State of NSW (Agency for Clinical Innovation). Sunflower Sydney: Agency for Clinical Innovation; 2022. Available online at: https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/chops/chops-key-principles/effective-communication-to-enhance-care/resources-and-useful-links (accessed July 2023).

16. Stroke Foundation. My Stroke Journey. Melbourne; Stroke Foundation, 2023. Available online at: https://strokefoundation.org.au/what-we-do/for-survivors-and-carers/stroke-journey-resources (accessed July 2023).

17. World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Available online at: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health (accessed July 2023).

18. Lynch E, Hillier S, Cadilhac D. When should physical rehabilitation commence after stroke: a systematic review. Int J Stroke 2014; 9: 468-478.

19. Jokinen H, Melkas S, Ylikoski R, et al. Post-stroke cognitive impairment is common even after successful clinical recovery. Eur J Neurol 2015; 22: 1288-1294.

20. Rowe FJ, Hepworth LR, Howard C, Hanna KL, Cheyne CP, Currie J. High incidence and prevalence of visual problems after acute stroke: an epidemiology study with implications for service delivery. PLoS ONE 2019; 14: e0213035.

21. Esposito E, Shekhtman G, Chen P. Prevalence of spatial neglect post-stroke: a systematic review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2021; 64: 101459.

22. Vafadar AK, Cote JN, Archambault PS. Effectiveness of functional electrical stimulation in improving clinical outcomes in the upper arm following stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 729768.

23. Premraj L, Camarda C, White N, et al. Tracheostomy timing and outcome in critically ill patients with stroke: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Crit Care 2023; 27: 132.

24. Bonvento B, Wallace S, Lynch J, Coe B, McGrath BA. Role of the multidisciplinary team in the care of the tracheostomy patient. J Multidiscip Healthc 2017; 10: 391-398.

25. Widgit Health. Critical care COVID-19 communication chart. Warwick: Widgit Health; 2020. Available online at: https://widgit-health.com/downloads/covid-19.htm (accessed July 2023).

26. Langhorne P, Wu O, Rodgers H, Ashburn A, Bernhardt J. A Very Early Rehabilitation Trial after stroke (AVERT): a phase III, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 2017; 21: 1-120.

27. Hubbard IJ, Parsons MW, Neilson C, Carey LM. Task-specific training: evidence for and translation to clinical practice. Occup Ther Int 2009; 16: 175-189.

28. Raine S, Meadows L, Lynch-Ellerington M. Bobath concept: theory and clinical practice in neurological rehabilitation. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013.

29. Murphy TH, Corbett D. Plasticity during stroke recovery: from synapse to behaviour. Nat Rev Neuro 2009; 10: 861-872.

30. Royal College of Physicians. Spasticity in adults: management using botulinum toxin. National guidelines, 2018. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2018. Available online at: http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/spasticity-adults-management-using-botulinum-toxin (accessed July 2023).

31. Kim JS. Post-stroke mood and emotional disturbances: pharmacological therapy based on mechanisms. J Stroke 2016; 18: 244-255.

32. Chan KL, Campayo A, Moser DJ, Arndt S, Robinson RG. Aggressive behavior in patients with stroke: association with psychopathology and results of antidepressant treatment on aggression. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006; 87: 793-798.

33. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Heart, stroke and vascular disease: Australian facts. Canberra: AIHW; 2023. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-diseases/hsvd-facts (accessed July 2023).

34. Johnston SC, Sidney S, Hills NK, et al. Standardized discharge orders after stroke: results of the quality improvement in stroke prevention (QUISP) cluster randomized trial. Ann Neurol 2010; 67: 579-589.