Fussy eating in toddlers and young children: implications and management

Fussy eating is common in young children but often resolves without intervention in the presence of positive eating behaviours in the home. However, if prolonged, fussy eating can result in nutrient deficiencies that need targeted ongoing support to improve appetite and the desire to eat.

- Fussy eating is common in young children.

- The causes of fussy eating may be related to the child (preferences), parents (feeding style and nutrition knowledge) or mealtime environment.

- Responsive feeding and shared family meals are helpful to minimise fussy eating.

- Key nutrients at risk of deficiency with prolonged fussy eating include iron, zinc, beta carotene and fibre.

- Medical implications of fussy eating can include iron deficiency, constipation, weight concerns and frequent illness.

- A small subset of children who are fussy eaters require targeted ongoing support from specialised healthcare professionals (e.g. dietitian, occupational therapist, speech therapist).

Food preferences begin to develop early in life and are influenced by flavours from the maternal diet via amniotic fluid in utero and breastmilk as a neonate. These preferences develop further with the introduction of solid foods.1 Babies are born with a preference for sweet and umami flavours over bitterness, which may explain the rejection of some foods, particularly bitter vegetables, in early weaning.2 However, repeated exposure to a food can result in an increased acceptance of that food. In general, repeated exposure to a wide range of foods in the first year of life leads to the acceptance of a wide range of tastes and textures. At about 18 months of age, many young children enter a period of neophobia, in which they develop an intense mistrust of new things, including new foods. This period also corresponds to an increasing sense of independence; therefore, it is common for children to become fussy with their food and reject both new and previously accepted foods.3 Furthermore, growth velocity slows at around 2 years of age, and toddlers often eat erratically to compensate for a reduction in energy requirements. It is difficult to put an exact figure on the prevalence of fussy eating because there is no single accepted definition, and behaviours tend to include a spectrum of food refusal.

Fussy (or picky) eating is loosely defined as consuming an inadequate variety of foods, with strong food preferences and rejection of both new and familiar foods.4,5 Although there is no universal method of measuring fussy eating, a meta-analysis of children younger than 30 months of age found that almost one-quarter (22%) of young children are fussy eaters.6 Data from the UK Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) suggests that fussy eating peaks at around 3 years of age, with just over half of children this age (54%) described by their parents as being fussy.5

Fussy eating can cause considerable stress for parents or caregivers, but it is a common phase in child development and often resolves with little or no intervention from a healthcare professional when positive eating behaviours are consistently modelled in the home. In some cases, fussiness resolves rapidly, whereas it may persist over a two- to three-year period in others.7 This article highlights the micronutrients at risk of deficiency and possible health implications in fussy eaters and practical management approaches for GPs.

Contributing factors

Children’s feeding behaviours develop from internal cues, opportunities to develop feeding skills, parental feeding styles and the feeding environment.8 Evidence suggests that early feeding practices play a key role in minimising both the impact and duration of fussy eating.9

Based on ALSPAC data, parental preoccupation with children’s fussiness at 2 years of age has been shown to predict a child’s fussiness at 3 years of age; nonresponsive feeding and subsequent pressure to eat, along with using food as a reward, also predicted fussy eating at 5 years of age.7,10,11 In contrast, lower levels of fussy eating:

- are associated with the timely introduction of solids (between 4 and 6 months of age, when the child is developmentally ready)

- promote age-appropriate progression through textures (lumps and finger foods by 9 months of age) and encourage autonomy (respecting hunger and satiety cues)

- offer opportunities to learn about new foods (eating with the child)

- are associated with sharing family meals and parental role modelling of a varied diet.3,12

Over-reliance on milk (and yoghurt) can also be a contributing factor of fussy eating. Although milk is an important source of calcium and protein, excessive consumption of milk can lead to early satiety and prevent children from developing a varied diet. Excessive milk consumption can also inhibit iron absorption because of competition between iron and calcium for uptake. It is recommended that milk be given at least an hour apart from an iron-rich meal. In children aged 1 to 3 years, in whom the recommended daily intake (RDI) for calcium is 500 mg, 400 mL (2 small cups) of cow’s milk or appropriately fortified plant-based milk (120 mg/100 mL) will meet their calcium requirements.13 In children aged 4 to 8 years, this increases to 700 mg/day or 600 mL (3 small cups).13 In infants, no RDI is set, but the average intake is set at 270 mg/day, which should be obtained mostly through breastmilk or infant formula.13 Supermarket milk products should not be the main source of calcium for infants younger than 1 year of age.

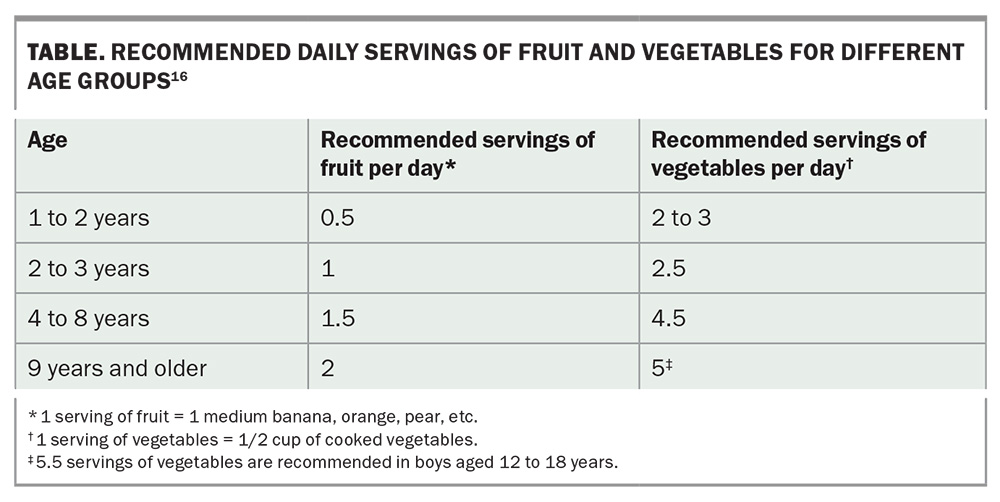

Furthermore, only 6.5% of adults in Australia meet the recommended servings of vegetables, and about 30% of energy intake is derived from discretionary foods (foods high in energy, fat, salt and sugar).14 This modelling can impact children’s eating habits and food choices, as evidenced by a similar pattern observed in children. About 20% of children in Australia meet the recommended number of servings of fruit (two per day), but less than 5% meet the recommended daily servings of vegetables (five per day) (Table).15,16 The absence of role modelling of desired eating behaviours impacts children’s food choices and acceptance.

A select group of children, including children with neurodevelopmental disorders, with sensory defensiveness or who have had a significant traumatic feeding incident (e.g. anaphylaxis, food protein enterocolitis syndrome, eosinophilic oesophagitis, choking), may continue to be fussy despite best efforts. Feeding is a multisystem skill, and sustained problematic feeding should be considered by a multidisciplinary paediatric team to ensure safety, appropriate skill development and nutritional adequacy. A paediatric occupational therapist, speech therapist and dietitian can aid with these assessments.

Nutrients at risk – a vicious cycle

Fussy eaters have been shown to have lower levels of iron, zinc and beta carotene than nonfussy eaters.12 Iron deficiency is the most common nutrient deficiency in early childhood and the most common cause of anaemia in children worldwide, including in developed countries.17 Iron deficiency, along with zinc deficiency, can perpetuate fussy eating by downregulating the appetite- stimulating hormone ghrelin, further reducing the desire to eat.18 Iron and zinc also play an important role in immune regulation, at a time when increased exposure to infection through the commencement of shared childcare services is prevalent.19-21 The associated bouts of illness also tend to accentuate fussy eating.

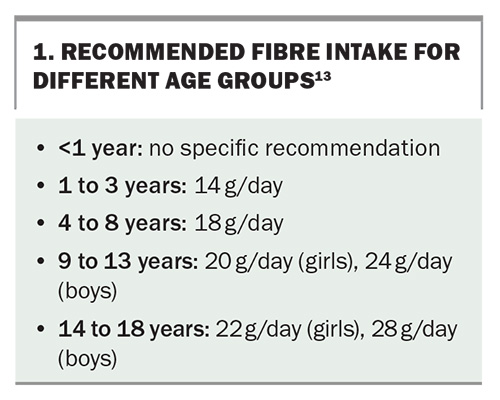

Exposure to less nutritious foods has effects on other aspects that are important for health. Although technically not a nutrient, fibre is important for gut health, as it stimulates gut transit and, in many cases, acts as a prebiotic to improve the gut microbiome. The recommended amounts of fibre intake for different age groups are listed in Box 1.13 These recommendations translate to the dietary guidelines for fruit and vegetable intake, along with a preference for wholegrains over refined cereals.13 Fibre is mostly found in fruit, vegetables, wholegrains, lentils and pulses, nuts and seeds. Children who are fussy eaters tend to eat less of these foods and higher quantities of refined carbohydrates (e.g. those in processed snacks), which predisposes them to higher rates of constipation.12 Constipation negatively impacts appetite in a similar manner to how iron deficiency can exacerbate fussy eating.

Treatment

Transient fussy eating responds to positive feeding practices. Parental or caregiver responsiveness to a child’s hunger and satiety cues and provision of developmentally appropriate food is termed ‘responsive feeding’. Responsive feeding is bidirectional and is the foundation of the approach known as Satter’s Division of Responsibility model (https://www.ellynsatterinstitute.org), in which parents decide what, where and when to provide food, and the child decides if and how much food they will eat without pressure. This approach promotes feeding autonomy and energy balance.22 It also assumes that parents are health literate and are including and modelling nutritious choices themselves.

When parents offer a variety of foods based on family meals, eat together with the child and model the desired eating behaviours, children are more likely to accept the same foods. Parents should be encouraged to adopt these principles in a structured mealtime environment. There are several good evidence-based resources available to parents and caregivers to support this style of eating; some examples are listed in Box 2.

If fussy eating has been present for an extended period, depending on the foods or food groups excluded, monitoring the child’s iron levels may be useful. Dietary iron requirements are high during the weaning period with infants aged 6 to 12 months needing as much dietary iron as an adult (11 mg/day), and only slightly less for toddlers (9 mg/day).13 It can be difficult for infants and toddlers to reach these targets when meat and fish are excluded or when excess dairy is consumed (>500 mL/day). Vegetarian sources of iron, including fortified breakfast cereals and breads, should be encouraged as these are generally well accepted and provide about 3 to 4 mg of iron per serving. Although less well absorbed than haem (animal) sources of iron, the addition of foods containing vitamin C, such as berries, kiwi fruit or citrus fruits, improve the absorption of iron from non-haem (vegetarian) sources.

Fussy eating may also be a consequence of gastrointestinal discomfort; therefore, common conditions such as coeliac disease, non-immunoglobulin E cow’s milk allergy and constipation should be excluded or managed if present. Functional constipation is a common complaint in toddlers. Including foods that have laxative effects, such as kiwi fruit, prunes, pears and apples, can sometimes help, but if not, a stool softener may be necessary. Fluid intake should be adequate and toileting routines in place. Increasing dietary fibre without adequate fluid intake can worsen constipation. A dietitian can help families improve their fibre intake and overall diet quality.

Children who present with extreme fussy eating and consistently refuse food across a number of different environments should be referred to an appropriate paediatric healthcare professional such as a (paediatric) dietitian, occupational therapist, speech therapist or psychologist with experience in feeding aversions. Red flags include consistent coughing or gagging after consuming food or drink, fewer than 20 ‘accepted’ foods and refusal of whole food groups with pronounced aversions to particular textures or presentations.23 A multidisciplinary approach is essential for such children. Considerations include the safety of swallowing, feeding skillset, sensory integration and nutritional adequacy during a time of growth and development.

Conclusion

Fussy eating is common in young children, and it often resolves without intervention from healthcare professionals when positive feeding practices are in place. Fussy eating and parental feeding practices have a bidirectional relationship, and nonresponsive approaches predict prolonged fussy eating. Prolonged fussy eating can cause nutrient deficiencies, particularly of iron and zinc, and these should be corrected to encourage appetite and improve the desire to eat. Fibre intake may also be of concern because of the lack of fruits and vegetables consumed, as low fibre intake leads to constipation and worsens fussy eating. Constipation should be proactively managed. There is a good body of evidence to support responsive feeding practices as the first-line treatment for fussy eating to ensure that the picky habits are transient. Finally, the mealtime environment plays an important role in ameliorating fussy eating among toddlers and young children. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Palmer was on the team of developers for the Grow & Go toolbox.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Dr Palmer thanks Fiona Nave and Kathy Beck, paediatric dietitians at Child D, for reviewing the article.

References

1. Mennella JA, Jagnow CP, Beauchamp GK. Prenatal and postnatal flavor learning by human infants. Pediatrics 2001; 107: E88.

2. Bell KI, Tepper BJ. Short-term vegetable intake by young children classified by 6-n-propylthoiuracil bitter-taste phenotype. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84: 245-251.

3. Howard AJ, Mallan KM, Byrne R, Magarey A, Daniels LA. Toddlers’ food preferences. The impact of novel food exposure, maternal preferences and food neophobia. Appetite 2012; 59: 818-825.

4. Dovey TM, Staples PA, Gibson EL, Halford JCG. Food neophobia and ‘picky/fussy’ eating in children: a review. Appetite 2008; 50: 181-193.

5. Taylor CM, Wernimont SM, Northstone K, Emmett PM. Picky/fussy eating in children: review of definitions, assessment, prevalence and dietary intakes. Appetite 2015; 95: 349-359.

6. Cole NC, An R, Lee S-Y, Donovan SM. Correlates of picky eating and food neophobia in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev 2017; 75: 516-532.

7. Taylor CM, Emmett PM. Picky eating in children: causes and consequences. Proc Nutr Soc 2019; 78: 161-169.

8. Gahagan S. Development of eating behavior: biology and context. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2012; 33: 261-271.

9. Wolstenholme H, Kelly C, Hennessy M, Heary C. Childhood fussy/picky eating behaviours: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2020; 17: 2.

10. Fries LR, Martin N, van der Horst K. Parent-child mealtime interactions associated with toddlers’ refusals of novel and familiar foods. Physiol Behav 2017; 176: 93-100.

11. Mallan KM, Jansen E, Harris H, Llewellyn C, Fildes A, Daniels LA. Feeding a fussy eater: examining longitudinal bidirectional relationships between child fussy eating and maternal feeding practices. J Pediatr Psychol 2018; 43: 1138-1146.

12. Taylor CM, Emmett PM. Picky eating in children: causes and consequences. Proc Nutr Soc 2019; 78: 161-169.

13. National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, New Zealand Ministry of Health. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2006. Available online at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/nutrient-reference-values-australia-and-new-zealand-including-recommended-dietary-intakes (accessed May 2024).

14. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Dietary behaviour - Adult fruit and vegetable consumption. Canberra: ABS, Australian Government; 2023. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/dietary-behaviour/latest-release#adult-fruit-and-vegetable-consumption (accessed May 2024).

15. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Dietary behaviour – Children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. Canberra: ABS, Australian Government; 2023. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/dietary-behaviour/latest-release#childrens-fruit-and-vegetable-consumption (accessed May 2024).

16. National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Recommended number of serves for children, adolescents and toddlers. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2024. Available online at: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/food-essentials/how-much-do-we-need-each-day/recommended-number-serves-children-adolescents-and-toddlers (accessed May 2024).

17. World Health Organization (WHO). Nutritional anaemias: tools for effective prevention and control. Geneva: WHO; 2017. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513067 (accessed May 2024).

18. Akarsu S, Ustundag B, Gurgoze MK, Sen Y, Aygun AD. Plasma ghrelin levels in various stages of development of iron deficiency anemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2007; 29: 384-387.

19. Hassan TH, Badr MA, Karam NA, et al. Impact of iron deficiency anemia on the function of the immune system in children. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e5395.

20. Ackland ML, Michalczyk AA. Zinc and infant nutrition. Arch Biochem Biophys 2016; 611: 51-57.

21. Collins JP, Shane AL. 3 - Infections associated with group childcare. In: Long SS, Prober CG, Fischer M, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2018: p. 25-32 e3.

22. Redsell SA, Slater V, Rose J, Olander EK, Matvienko-Sikar K. Barriers and enablers to caregivers’ responsive feeding behaviour: a systematic review to inform childhood obesity prevention. Obes Rev 2021; 22: e13228.

23. Toomey KA, Ross ES. SOS approach to feeding. Perspectives on Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders (Dysphagia) 2011; 20: 82-87.