Childhood insomnia: assessment and interventions

Paediatric insomnia is an underdiagnosed condition. Chronic insufficient sleep is detrimental to a child’s physical, emotional, cognitive and social development. GPs play a central role in identifying children's sleep problems and commencing early intervention, as simple behavioural management strategies can be effective.

- Childhood insomnia is common and often missed in paediatric patient evaluations.

- There are significant negative effects of chronic inadequate sleep on children’s daytime functioning and family dynamics.

- When ascertaining a sleep history, clinicians should understand what constitutes the recommended total sleep times for different age groups and request families to maintain a sleep diary.

- Childhood insomnia can be classified into the following categories: behavioural insomnia of childhood, psychophysiological insomnia, transient sleep disturbances and idiopathic insomnia.

- Management of childhood insomnia includes understanding the principles of sleep optimisation strategies (sleep hygiene) and using evidence-based and targeted behavioural interventions.

- If concerned about other sleep disorders, including obstructive sleep apnoea and restless legs syndrome, early referral of the child to a paediatrician or paediatric sleep specialist is recommended.

Insomnia is defined by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders Third Edition (ICSD-3) as persistent difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation or quality that occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep, and results in some form of daytime impairment.1 Daytime symptoms include daytime sleepiness, fatigue, decreased performance and cognitive function, low mood and behavioural problems (hyperactivity, impulsivity, aggression).2 The estimated prevalence of insomnia in childhood is between 20% and 40%. Children with developmental disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, depression or anxiety have more than double the incidence of sleep disturbances compared with typical children.3,4 The sleep issues in this group of children with special needs deserve more detailed and specific attention than the scope of this article allows. There is some evidence for the persistence of childhood insomnia and sleep disorders into adolescence and young adulthood.5,6

It is increasingly recognised that chronic insufficient sleep and inadequate sleep quality is detrimental to a child’s physical, emotional, cognitive and social development.7 Insomnia during adolescence is also a significant risk factor for current and future development of depression and suicide.2 Families also frequently report impairment in caregivers’ daytime functioning and worsening of their own psychological and medical health.8

Paediatric insomnia is frequently not addressed within primary care, as parents generally do not mention their concerns to their GP, or a sleep history is not ascertained by the clinician. Primary healthcare practitioners play a central role in commencing early interventions for sleep issues in childhood and simple management strategies can be effective at this level.4,9 This article summarises the aetiology of paediatric insomnia and provides a practical approach that can be used by primary healthcare providers in the management of insomnia. Sleep issues in adolescents and young infants deserve more specific attention and will not be covered in this article.

Sleep behaviours in childhood

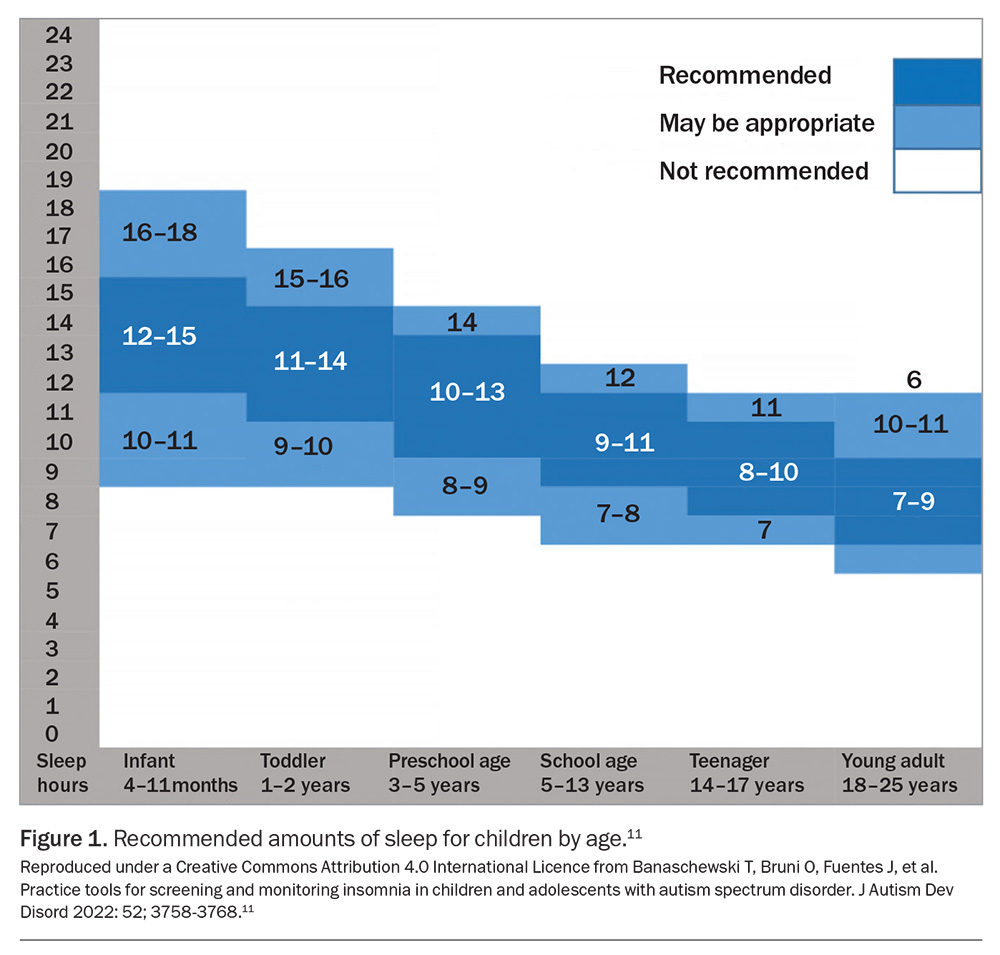

When engaging with families and children about problematic or insufficient sleep, it is important to understand what constitutes ‘normal’ sleep in children.10 Cultural, environmental and social influences should also be considered when assessing a child’s sleep.10 The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has provided recommendations for age-specific ranges of sleep amounts needed per 24 hours to promote optimal health, which is a useful guide in the primary care setting (Figure 1).11,12

The physiological, developmental and socioenvironmental changes that occur throughout childhood also contribute to sleep behaviours in childhood. Some changes in sleep behaviours include:

- a decline in the average daily sleep duration from infancy through to adolescence; in particular, a notable decline in daytime sleep (scheduled napping) between 18 months and 5 years of age

- a gradual shift to a later bedtime and sleep-onset time, which accelerates from early to mid-adolescence

- irregularity of sleep–wake patterns with significant discrepancies between school night and nonschool night bedtimes and awake times.10

Parental recognition of sleep problems in children is also variable; those with younger children are often more aware, particularly because of the degree of disruption it causes to their own sleep. There is also a common misconception that children ‘grow out of’ sleep problems. The persistence and recurrence of infant sleep problems into early childhood is well documented.10 Intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors including chronic illness, neurodivergent disorders, challenging temperaments, parental mental health issues and family stress may predispose a child to developing a more chronic sleep disturbance.

Assessment

History

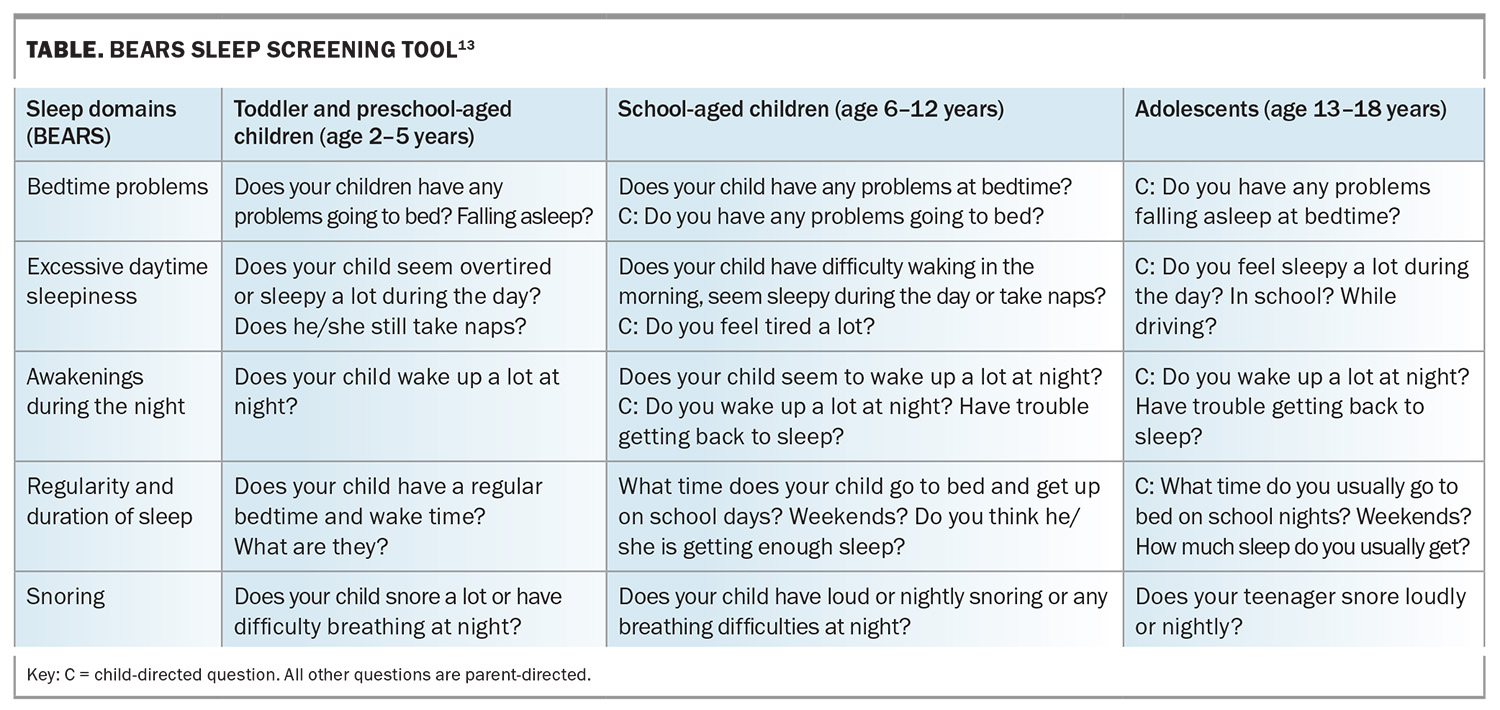

When assessing a child with sleep problems, the practitioner should take a thorough history and clinical examination. The BEARS mnemonic is useful to remind physicians of important aspects of sleep quality in children (Table).13 It is also important to ask families and children about:

- the duration, frequency and variability of sleep difficulties

- the child’s sleep environment (including lighting, noise level, room sharing and bed type), sleep habits (including sleep associations) and bedtime routines

- the presence of screens, such as mobile phones and other devices, and the type of applications used

- the time of onset of sleep problems (e.g. during a time of stress)

- abnormal movements, behaviours or breathing symptoms during sleep

- other daytime symptoms including irritability, hyperactivity or inattention

- previous interventions, medications or strategies used for sleep difficulties

- the child’s developmental, school, medical, psychiatric, family and social history.7,13

Sleep is also an important part of screening for adolescent health. Insomnia in adolescence is beyond the scope of this article; however clinicians can refer to the Evidence to Practice: Assessment and treatment of sleep problems in help-seeking young people by Orygen (available online at: https://www.orygen.org.au/Training/Resources/Physical-and-sexual-health/Evidence-summary/Assessing-and-responding-to-sleep-problems-in-youn).

Physical examination

A physical examination should be conducted for all children and young adolescents being evaluated for sleep concerns. The following key features should be considered, although they may often be unremarkable:

- growth parameters

- growth failure or obesity can be associated with sleep-disordered breathing

- general appearance or behaviour, including hyperactivity, irritability, level of fatigue or sleepiness

- head and neck examination findings

- suspected obstructive sleep apnoea with adenotonsillar hypertrophy

- evidence of atopic disease: allergic ‘shiners’, bogginess of nasal mucosa, cobble-stoning of the soft palate.

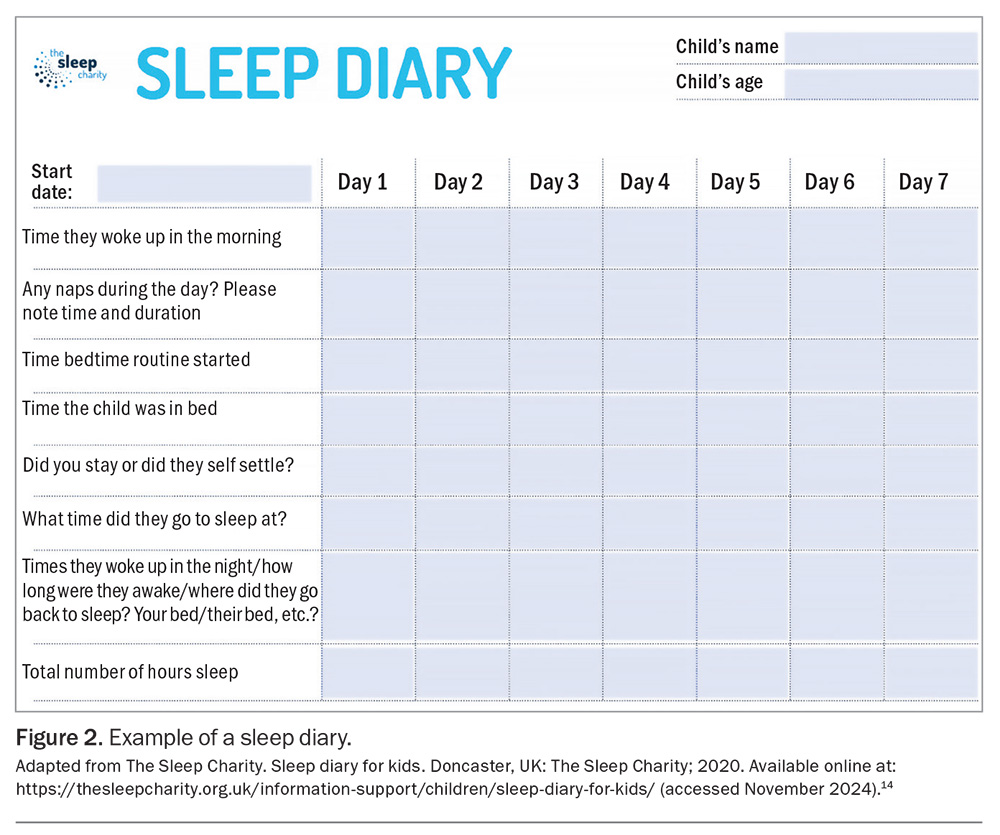

Sleep diary

Asking parents to record a sleep diary for at least two weeks is a useful way of establishing sleep patterns (Figure 2).14 Parents should record information during each 24-hour period. More accurate information may be obtained if the child is older and able to complete the sleep diary on their own. The following information should also be included in the diary:

- the sleep environment (e.g. whether the child has their own bedroom, the distance from the parents’ bedroom, whether the bed is shared)

- the time the child gets into bed and the time to fall asleep (sleep latency)

- parental or other carer’s presence at sleep onset

- the length of time the child spends lying in bed awake in the morning

- the time the child gets out of bed in the morning

- daytime alertness or sleepiness

- times that meals and snacks are consumed during the day, especially if meals are consumed just before bedtime

- time the child exercises.

Polysomnography

In most cases, children presenting with insomnia do not require an overnight sleep study unless there is a history or risk factors suggestive of obstructive sleep apnoea or periodic limb movement disorder.7

Types of sleep problems causing sleeplessness

Although succeeded by the ICSD-3, for the purposes of clinical evaluation and management in clinical practice, it is useful to consider the contributors to childhood insomnia in the following categories as set out in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders Second Edition:

- behavioural insomnia of childhood

- psychophysiological (conditioned) insomnia

- transient sleep disturbances

- idiopathic insomnia.15

Behavioural insomnia of childhood

Behavioural insomnia is most common in children aged 5 years and younger. It is often a consequence of difficulties with parental limit settings and maladaptive sleep onset associations.16

Sleep onset-association subtype

Children who become accustomed to falling asleep only under certain conditions, such as with a specific person or object assisting them with going to or staying asleep, fall into the sleep onset-association subtype. This often occurs in younger infants, resulting in their awakening at the end of a sleep cycle when a brief arousal occurs and requiring parental intervention to help them return to sleep. It is associated with prolonged night awakenings. Nocturnal feeding and drinking can worsen the condition.

Limit-setting subtype

In this limit-setting insomnia subtype, parents have lost control of their child’s behaviour at bedtime or during awakenings from sleep. This is often secondary to inconsistencies in or a lack of enforcement of regular bedtimes and rules, or oppositional behaviour in the child. This subtype occurs particularly in preschool-aged and older children. Other comorbidities, including asthma, anxiety and medication use, can exacerbate this subtype of insomnia.

Psychophysiological (conditioned) insomnia

Psychophysiological insomnia develops secondary to cognitive and behavioural responses that interfere with sleep onset or maintenance.7,16 These include:

- an inability to fall asleep when desired but an ability to fall asleep easily during other activities, such as reading or watching television

- sleeping poorly at home but better when away from home or when not carrying out bedtime routines

- anxiety about falling or staying asleep

- excessive worrying about the previous day or future events.

It is important to ask about precipitating factors, including acute stress, poor sleep habits, caffeine consumption or inappropriate daytime napping.

Transient sleep disturbances

Transient sleep disturbances occur in a child with previously normal sleep and is usually self-limited.1,16 Disruption of the sleep schedule, such as frequent night awakening and delayed sleep initiation, can occur because of stressful life events, illnesses, jet lag following travel or the arrival of a new baby. These disturbances can become chronic if parents respond in a way that reinforces these inappropriate sleep behaviours. For this sleep concern to become chronic insomnia, it needs to occur at least three times per week and be associated with daytime symptoms for at least three months, as per ICSD-3 criteria.

Idiopathic Insomnia

Idiopathic insomnia is described as a life-long inability to obtain adequate sleep, typically beginning in early childhood (often birth). It is presumed to be caused by an abnormality in the neurological control of the sleep–wake system.16

Behavioural interventions

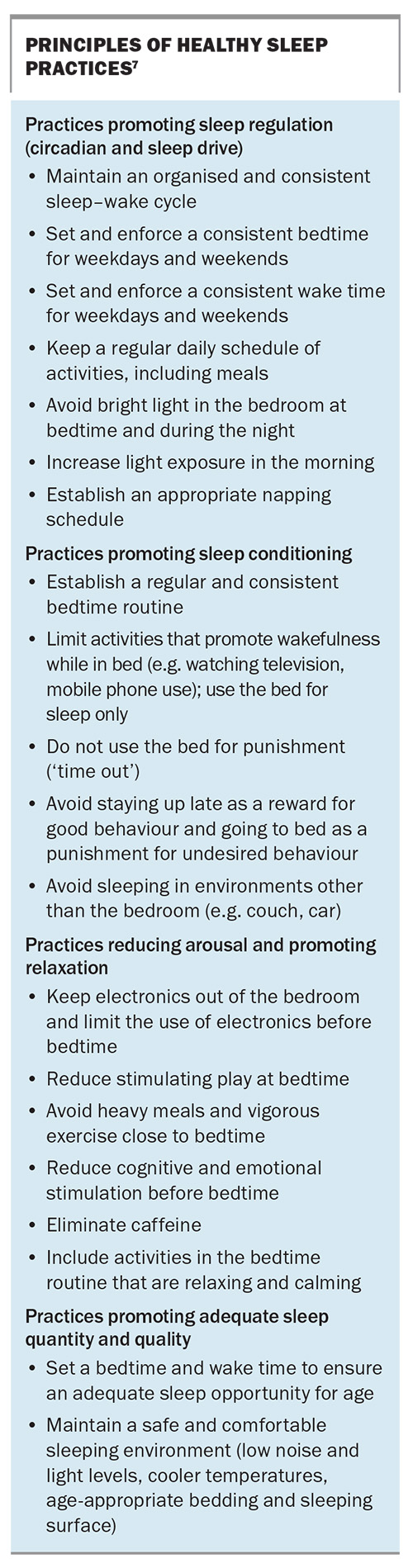

There is substantial empirical evidence that supports the use of behavioural strategies for the management of paediatric insomnia. Adopting basic principles of healthy sleep is integral in undertaking a behavioural management plan (Box).7

Sleep onset-association insomnia

Two general approaches have been suggested to enable the development of ‘self-soothing’ and allow the child to fall asleep independently. These are the unmodified and graduated extinction approaches. The success of these approaches relies on parents’ ability to be consistent in their approach and manage the protest behaviour that will temporarily escalate before subsiding.7 An improvement is often seen in three to seven days if remaining consistent with the approach.

Unmodified extinction

The unmodified extinction approach involves placing the child in the intended sleep location and leaving the room. There is no further input by the caregiver, even if the child protests, until the morning. Although this has been shown to be highly effective in research studies, it is often not appealing nor adopted by most parents.

Graduated extinction

Controlled comforting

The controlled comforting approach involves parents being instructed to place the child in their bed or cot drowsy but awake and leave the room. They are requested to ignore bedtime crying and outbursts for specified periods of time: a fixed schedule (e.g. every 5 minutes) or waiting progressively longer intervals (e.g. 5 minutes, then 10 minutes, then 15 minutes). Following the check-in, parents will leave the room, and the process is continued until the child is asleep.7,17,18

Camping out

The camping out approach involves the parent sitting on a chair or sleeping on a mattress near the child’s cot or bed to be present during night awakenings. Initially, the parent will stay with the child as they fall asleep and gradually withdraw their presence from the child’s bedroom over one to three weeks.7,17,18

Limit-setting insomnia

Clear, firm and concise bedtime rules are crucial for the management of limit-setting insomnia. Using positive reinforcement, such as reward systems and sticker charts after the completion of a targeted goal, can be helpful for older children. Although reward systems are less likely to work in younger children who sleep in a cot, a barrier is already in place and parents must persist with consistency in enforcing bedtime rules.

Behavioural interventions for psychophysiological (conditioned) insomnia

Psychophysiological insomnia occurs predominantly in older children and adolescents. Behavioural strategies that can be useful for this group include:

- stimulus control involving using the bed only for sleep and leaving the bed when unable to sleep and reading a book in the lounge

- sleep restriction involving limiting the time in bed to actual sleep time

- relaxation strategies including deep breathing exercises and guided visualisation

- cognitive-behavioural strategies, such as a dedicated worry time and cognitive restructuring.

Anxiety can often manifest as insomnia. A referral of the child to a clinical psychologist should be considered when it seems that the sleep problems might be the tip of an iceberg, especially when some behavioural measures do not work.

The bedtime pass technique

The bedtime pass technique is an evidence-based technique useful in children aged 3 to 6 years.19,20 The technique involves putting the child into bed and providing a card or ticket that is exchangeable for one ‘free’ trip out of the room or one parent visit to satisfy an acceptable request (e.g. drink or hug). The child must surrender the pass or ticket once redeemed. Further subsequent bids for attention are ignored as per the ‘contract’. For younger children, if the pass remains in the child’s possession the next day, an immediate reward is presented the next morning. For older children, an accumulation of the passes (one can be printed for each night) at the weekend can be exchanged for prizes: the more passes retained, the bigger the reward claimed.

Pharmacological interventions

Most sleep problems in children can be managed by behavioural therapy alone. In a limited population, however, pharmacotherapy may be used in conjunction with first-line behavioural therapy.21 Before considering pharmacotherapy, the clinician should establish the cause of insomnia in the child and if any behavioural or pharmacological interventions have been used previously. Clinicians must evaluate cases on an individual basis and discuss suitable behavioural interventions. Pharmacotherapy should only be considered following this process.

There is currently a lack of evidence-based literature related to safety, efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological agents in children. Off-label medications and over-the-counter sleep aids are often prescribed. Medications, including melatonin, antihistamines and alpha-agonists, are suggested for use with caution in children with insomnia. A referral to a paediatrician or sleep physician is recommended if behavioural measures do not work, or if there are other potential contributors to insomnia, such as periodic limb movement disorder and sleep-disordered breathing.

Melatonin

Melatonin has been increasingly used over the past decade as a sleeping aid.22,23 Melatonin is a neurohormone that is enzymatically synthesised from the amino acid tryptophan in the pineal gland. The synthesis and secretion of melatonin is regulated by the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus. It is the hormone that gives the signal to ‘switch to night mode’ and reinforces the circadian clock. Efficacy data suggest that melatonin is safe and effective, particularly in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities.24 Efficacy data on its use in neurotypically developing children are less robust. No serious side effects have been reported with melatonin use.25

Although the availability of melatonin is regulated in Australia, many families continue to source melatonin from overseas where it is regarded as a supplement and not required to adhere to strict quality measures. In a recent report, the variability between batches and content of melatonin ranges from –83% to 478%.26 Further, the melatonin is not always pure and frequently has been found to be contaminated with serotonin. A chromatography study of melatonin content in 30 common brands of melatonin gummies in the USA revealed no melatonin in one of 30 brands, with some containing significant amounts of cannabis derivatives.27

Modified-release melatonin is TGA approved for children and adolescents aged 2 to 18 years with autism spectrum disorder or Smith–Magenis syndrome (PBS listed for the latter condition), if sleep hygiene measures have been insufficient. If treatment with melatonin is initiated for children aged 2 years and older with chronic insomnia, close follow up is essential.28,29

Antihistamines

Histamine is considered a wakefulness promoter. Antihistamines, particularly H1 receptor blockers, are postulated to act in the central nervous system by blocking or inactivating histamine release. First-generation oral sedating antihistamines, such as promethazine and dexchlorpheniramine, should not be given to children younger than 2 years of age for any indication.21 Despite widespread off-label use, studies in children have demonstrated variable results.30,31

Alpha-agonists

Clonidine is a central and peripheral alpha-2-adrenergic receptor agonist commonly used to treat hypertension and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder but also found to have a sedative effect.21 The exact mechanism is unclear, but it has been postulated that it acts on presynaptic terminals of noradrenergic neurons that lead to decreased norepinephrine release. There are limited clinical data on its safety and efficacy.

Follow up and when to refer

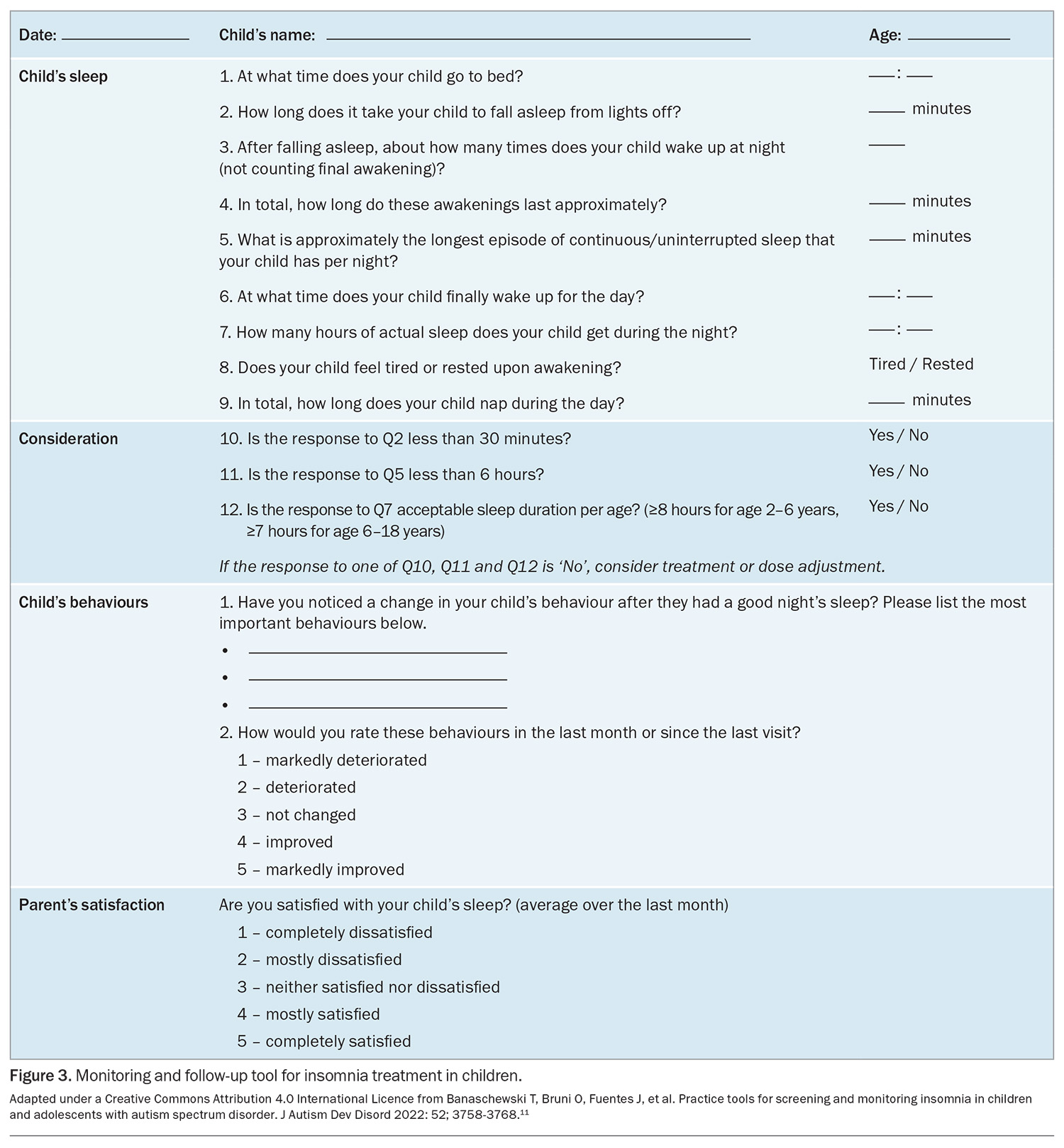

Children and their caregivers should be followed up within two to four weeks of starting behavioural management. A structured follow-up tool, such as that shown in Figure 3, can be used.11 If sleep has not improved at the time of follow up, it is important to consider the limitations including inconsistencies in approaches and discord in the family.

Referral to a paediatrician or paediatric sleep physician should be considered if:

- symptoms of other underlying sleep disorders, including obstructive sleep apnoea or restless legs syndrome, are present

- there is concern about other parasomnias

- there is concern about psychiatric or psychological issues

- the effects of insomnia are severe.13

Conclusion

Although insomnia occurs frequently in childhood, it can go unrecognised, as parents may not mention their concerns to their doctor, or a sleep history is not ascertained by the clinician. Identifying triggers and perpetuating factors is essential to help proceed with necessary behavioural interventions. An important role of the GP is to identify children’s sleep problems, commence early intervention and refer children to specialty services, if needed.

Data on the use of pharmacotherapy for paediatric insomnia are limited. Pharmacotherapy should not be the first-line or sole treatment strategy for paediatric insomnia and should always be used in conjunction with behavioural strategies. A low threshold for referral of the child to a paediatrician or sleep physician is recommended if medications are to be considered, especially in the younger age group, after appropriate behavioural interventions, or if there are potential other underlying medical issues. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Krishnananthan: None. Dr Saddi has received payment or honoraria from Aspen Pharmaceuticals and Link Pharmaceuticals. Associate Professor Teng has received honoraria as an invited speaker for Aspen Pharmaceuticals and SomnoMed.

References

1. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

2. Uccella S, Cordani R, Salfi F, et al. Sleep deprivation and insomnia in adolescence and implications for mental health. Brain Sci 2023; 13: 569.

3. Bruni O, DelRosso LM, Mogavero MP, Ferri R. Is behavioural insomnia "purely behavioural"? J Clin Sleep Med 2022; 18: 1475-1476.

4. Waters KA, Suresh S, Nixon GM. Sleep disorders in children. Med J Aust 2013; 199: S31-S35.

5. Armstrong JM, Ruttle PL, Klein MH, Essex MJ, Benca RM. Associations of child insomnia, sleep movement, and their persistence with mental health symptoms in childhood and adolescence. Sleep 2014; 37: 901-909.

6. Gregory AM, O’Connor TG. Sleep problems in childhood: a longitudinal study of developmental change and association with behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002; 41: 964-971.

7. Owens JA, Moore M. Insomnia in infants and young children. Paediatr Ann 2017; 46: e321-e326.

8. Gissandaner TD, Stearns MA, Sarver DE, Walker B, Ford H. Understanding the impact of insufficient sleep in children with behavior problems on caregiver stress: results from a U.S. national study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2023; 28: 1550-1564.

9. Honaker SM, Meltzer LJ. Sleep in pediatric primary care: a review of the literature. Sleep Med Rev 2016; 25: 31-39.

10. Owens J. Classification and epidemiology of childhood sleep disorders. Primary Care 2008; 35: 533-546.

11. Banaschewski T, Bruni O, Fuentes J, et al. Practice tools for screening and monitoring insomnia in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2022: 52; 3758-3768.

12. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 2016; 12: 785-786.

13. Mindell JA, Owens JA. A Clinical guide to paediatric sleep. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015.

14. The Sleep Charity. Sleep diary for kids. Doncaster, UK: The Sleep Charity; 2020. Available online at: https://thesleepcharity.org.uk/information-support/children/sleep-diary-for-kids/ (accessed November 2024).

15. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 2nd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

16. Bruni O, DelRosso LM, Mogavero MP, Angriman M, Ferri R. Chronic insomnia of early childhood: phenotypes and pathophysiology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2022; 137: 1-9.

17. Kang EK. Kim SS. Behavioural insomnia in infants and young children. Clin Exp Paediatr 2020; 64: 111-116.

18. Kahn M, Juda-Hanael M, Livne-Karp E, Tikotzky L, Anders TF, Sadeh A. Behavioral interventions for pediatric insomnia: one treatment may not fit all. Sleep 2020; 43: zsz268.

19. Friman PC, Hoff KE, Schnoes C, Freeman KA, Woods DW, Blum N. The bedtime pass: an approach to bedtime crying and leaving the room. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999; 153: 1027-1029.

20. Moore BA, Friman PC, Fruzzetti AE, MacAleese KM. Brief report: evaluating the bedtime pass program for child resistance to bedtime – a randomized, controlled trial. J Paediatr Psychol 2007; 32: 283-287.

21. Ekambaram V, Owens J. Medications used for pediatric insomnia. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2021; 30: 85-99.

22. Esposito S, Laino D, D’Alonzo R, et al. Pediatric sleep disturbances and treatment with melatonin. J Transl Med 2019; 17: 77.

23. Rolling J, Rabot J, Schroder CM. Melatonin treatment for paediatric patients with insomnia: is there a place for it? Nat Sci Sleep 2022; 14: 1927-1944.

24. Schroder CM, Banaschewski T, Fuentes J, et al. Pediatric prolonged-release melatonin for insomnia in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2021; 22: 2445-2454.

25. Edemann-Callessen H, Andersen HK, Ussing A, et al. Use of melatonin for children and adolescents with chronic insomnia attributable to disorders beyond indication: a systematic review, meta-analysis and clinical recommendation. eClinicalMedicine 2023; 61: 102049.

26. Grigg-Damberger MM, Ianakieva D. Poor quality control of over-the-counter melatonin: what they say is often not what you get. J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13: 163-165.

27. Cohen PA, Avula B, Wang YH, Katragunta K, Khan I. Quantity of melatonin and CBD in melatonin gummies sold in the US. JAMA 2023; 329: 1401-1402.

28. Clinical Excellence Commission. Use of melatonin in NSW Health facilities. Sydney: NSW Medicines Formulary; 2023. Available online at: https://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/keep-patients-safe/medication-safety/nsw-medicines-formulary/resources (accessed November 2024).

29. Therapeutics Good Administration (TGA). Australian Public Assessment Report for MELATONIN-LINK, IMMELA, MELAKSO, VOQUILY. Canberra: Australian Government; 2024. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-03/auspar-melatonin-link-immela-melakso-voquily-240313.pdf (accessed November 2024).

30. Krzystanek M, Krysta K, Pałasz A. First generation antihistaminic drugs used in the treatment of insomnia – superstitions and evidence. Pharmacother Psychiatr Neurol 2020; 36: 33-40.

31. Felt BT, Chervin RD. Medications for sleep disturbances in children. Neurol Clin Pract 2014; 4: 82-87.