Adrenaline injector devices: a 2024 update on prescribing

Adrenaline (epinephrine) is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis, and two types of adrenaline injector devices are available for use in Australia on the PBS. Prescribers need to be aware of the different instructions for their use and recent changes to adrenaline dose recommendations.

- Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening allergic reaction that can affect people of any age.

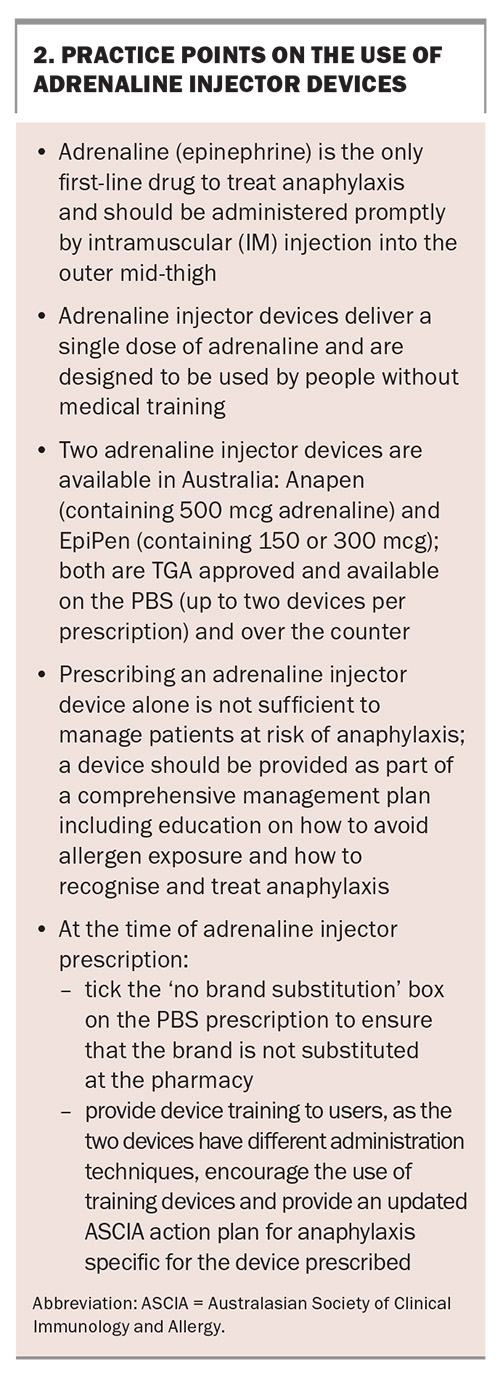

- Adrenaline is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis and should be given promptly by intramuscular injection into the outer mid-thigh; there are no contraindications for adrenaline in the management of anaphylaxis.

- Adrenaline injector devices allow for easy, prompt administration of adrenaline and are designed to be used by people without medical training. There are two devices listed on the PBS: Anapen and EpiPen.

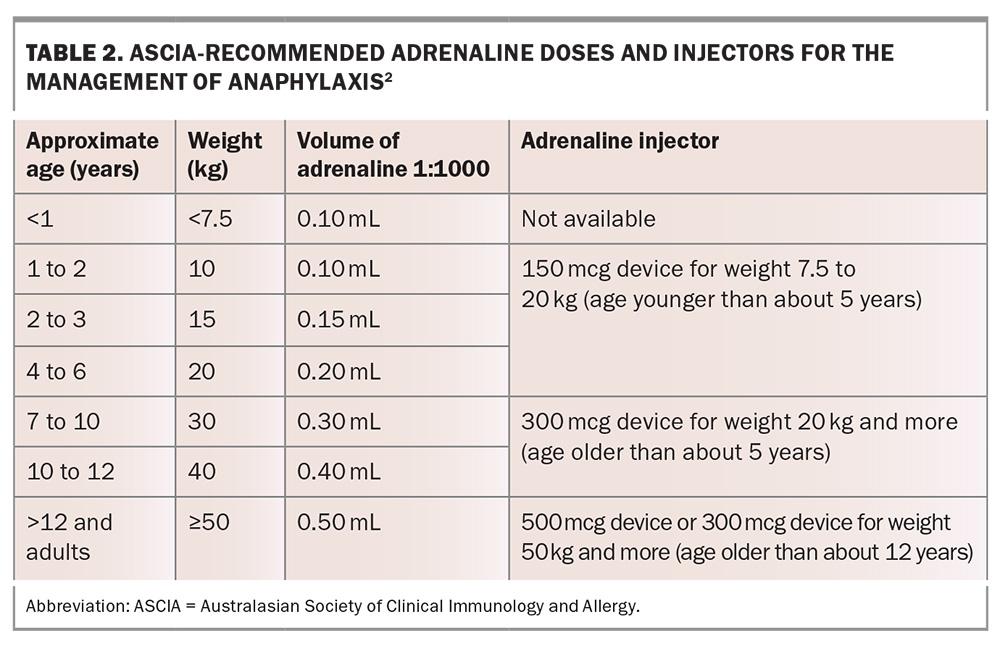

- The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA) recommends a 150 mcg device for patients weighing between 7.5 and 20 kg, a 300 mcg device for patients weighing between 20 and 50 kg, and a 300 mcg or 500 mcg device for patients weighing 50 kg or more.

- Since its launch in Australia on 1 September 2021, Anapen has been available in three sizes (150 mcg, 300 mcg and 500 mcg); however, only the 500 mcg device will continue to be available. EpiPen will continue to be available in 150 mcg and 300 mcg doses.

Anaphylaxis is a severe, potentially life-threatening allergic reaction, and intramuscular (IM) adrenaline (epinephrine) is the treatment of choice.1-4 Adrenaline injector devices have been available for more than 40 years and allow for rapid administration of IM adrenaline by the patient or a lay person.5-7 In Australia, EpiPen has been available on the PBS since 2003. From 2021, a second type of adrenaline injector device that can deliver a higher dose is also available on the PBS: Anapen. This article discusses the role of adrenaline injector devices in treating anaphylaxis and how to prescribe them, including dose and patient education, as well as comparing EpiPen and Anapen.

What are adrenaline injector devices?

Adrenaline injectors are single-use devices that deliver a set dose of adrenaline, designed for use by people without medical training to treat anaphylaxis. They are designed to keep adrenaline levels stable and have an expiry date in excess of one year after manufacture. Adrenaline is the only first-line drug to treat anaphylaxis and should be administered promptly by IM injection into the outer mid-thigh.1-3 IM administration has been the route of choice for optimal delivery of adrenaline in treating anaphylaxis for more than 20 years.1,3,4,8 There are no contraindications to the use of IM adrenaline to treat anaphylaxis.2,4

Adrenaline is a nonselective adrenergic agonist with a rapid onset of action. Adrenaline acts to reduce airway mucosal oedema, induce bronchodilation, induce vasoconstriction and increase cardiac contraction strength.1,4

Adrenaline injector devices available in Australia

Two adrenaline devices are TGA approved and available in Australia, with both listed on the PBS: Anapen (500 mcg dose) and EpiPen (containing 150 or 300 mcg doses). A generic device similar to EpiPen is also PBS listed.

Most countries have multiple brands of adrenaline injector devices available, and both EpiPen and Anapen are widely used in other countries. Since its launch in Australia on 1 September 2021, Anapen has been available in three sizes (150 mcg, 300 mcg and 500 mcg); however, only the 500 mcg device will continue to be available. Due to a lack of demand, supply of the Anapen 300 mcg device ceased in July 2024 and the 150 mcg device in September 2024.

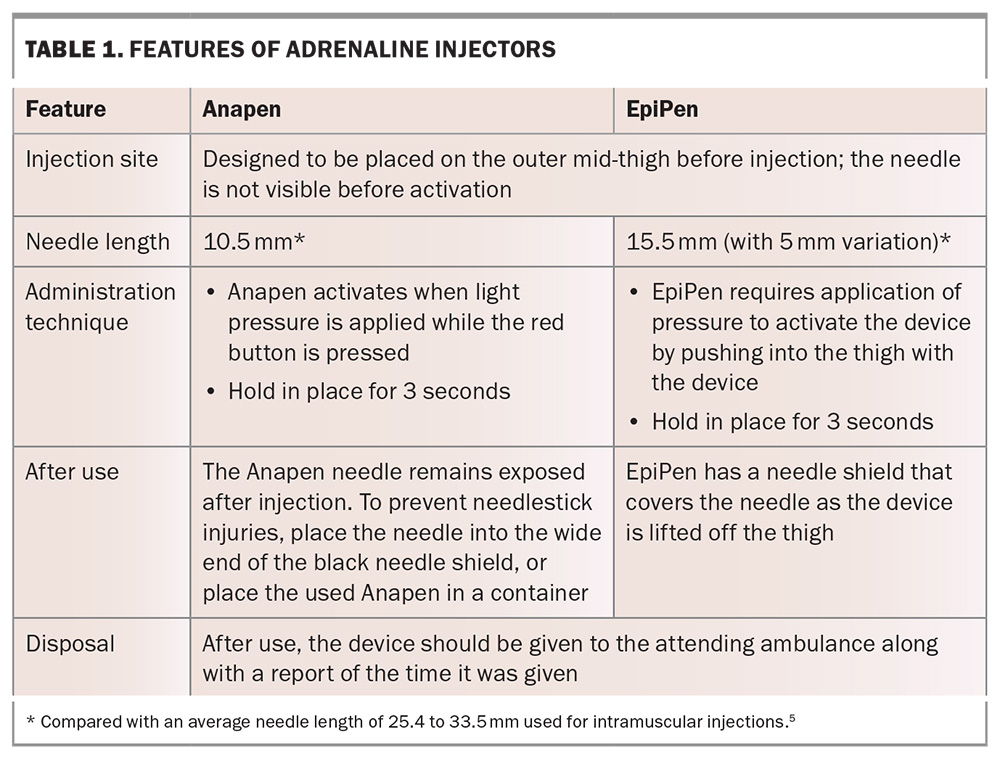

The features of Anapen and EpiPen are compared in Table 1. Patient cost is the same for both devices, as they are subsidised by the PBS and have similar over-the-counter prices.

Innovative therapies

Despite their effectiveness, there are limitations around currently available adrenaline injector devices including their size, restricted dose range and needle phobia. Research into alternative methods of adrenaline delivery is ongoing, with the focus on intranasal and sublingual preparations. Studies have compared the pharmacokinetic and clinical data of these delivery systems with manual syringes and autoinjectors in healthy individuals, given the ethical challenges of conducting studies in patients experiencing anaphylaxis. Intranasal and sublingual adrenaline delivery show concentration (Cmax) and time to maximum concentration (Tmax) values that are comparable with those for EpiPen, as well as similar effects on systolic blood pressure and heart rate.9 The most common side effects of nasal adrenaline devices are nasal discomfort and throat irritation.10 The importance of correct device technique to ensure drug delivery and minimise nasal drainage in real-life settings will need to be determined.

The first noninjectable adrenaline device was approved in June 2024 when the European Medicines Agency granted marketing authorisation for an intranasal device containing a single dose of 2 mg adrenaline, intended for use in adults and children weighing 30 kg or more with anaphylaxis. The US Food and Drug Administration followed suit and approved an intranasal device in August 2024, having requested additional studies following its 2023 application, which was not approved.

In May 2024, it was announced that there were plans to apply for regulatory approval of an intranasal device in Australia. It is anticipated that other innovative adrenaline devices will become available with research continuing in this area.

What are the advantages of multiple adrenaline devices being available?

Most countries have multiple brands of adrenaline devices available for the following reasons:

- to ensure continued supply of life-saving adrenaline, particularly if one brand has stock shortages

- to provide clinicians with a choice of dose, as:

– they may prefer to prescribe a higher dose (500 mcg device) for people who weigh more than 50 kg

– a 500 mcg dose may potentially prevent the need for further doses of adrenaline (which is important because of increasing ambulance delays and many people carrying only one device) - to encourage suppliers to provide devices with a longer shelf life

- to provide choice for consumers to access devices with points of difference to best suit their needs.

When to use an adrenaline device

Adrenaline devices are used for the first-line treatment of anaphylaxis. Anaphylaxis is a severe allergic reaction that is often under-recognised and undertreated.1,3,11 Definitions vary worldwide, but the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA) defines anaphylaxis as any of the following:

- any acute-onset illness with typical skin features (urticarial rash, erythema [flushing] or angioedema), plus involvement of respiratory, cardiovascular or persistent severe gastrointestinal symptoms (gastrointestinal symptoms of any severity are a symptom of anaphylaxis to insect stings or injected drugs)

- any acute onset of hypotension, bronchospasm or upper airway obstruction where anaphylaxis is considered possible, even if typical skin features are not present.2

The ASCIA definition is consistent with the criteria published in the World Allergy Organization Anaphylaxis Guidance 2020.3

Adrenaline devices may be self-administered or given by people without medical training. They are also sometimes used to treat anaphylaxis in medical facilities, as they contain a fixed dose of adrenaline, which may reduce the risk of overdose and delays in administration.

Although most anaphylactic reactions are not fatal, reactions are unpredictable.12,13 Factors that may affect the severity of reactions include the dose of the allergen, route of exposure, presence of asthma, other drug use (alcohol, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors) and exercise, but importantly, there are no reliable clinical predicators of a severe reaction.3,4,12 Although patients who have previously had anaphylaxis would be considered at risk of subsequent severe reactions, a history of previously mild reactions is not a good predictor of subsequent reaction severity.12,14 Early use of IM adrenaline can treat the symptoms of anaphylaxis and reduce the risk of fatal reactions, although these sometimes still occur.1,3,4,14,15

Antihistamines and corticosteroids do not treat or prevent anaphylaxis and should not be used in the first-line treatment of anaphylaxis.1,12 Patients may fear adrenaline or feel reassured that past reactions with respiratory or cardiovascular symptoms have resolved either without treatment or with the use of antihistamines or corticosteroids. However, any apparent benefit is not because of the action of either medication, the onset and mechanisms of action of which will not reverse symptoms of anaphylaxis, but because of endogenous responses, which may vary with each reaction.1,4,12 Although antihistamines are listed on the ASCIA action plans to treat mild to moderate symptoms of allergic reactions, such as hives, progression to respiratory or cardiovascular symptoms should be treated with an adrenaline device without delay.

How to use adrenaline injector devices

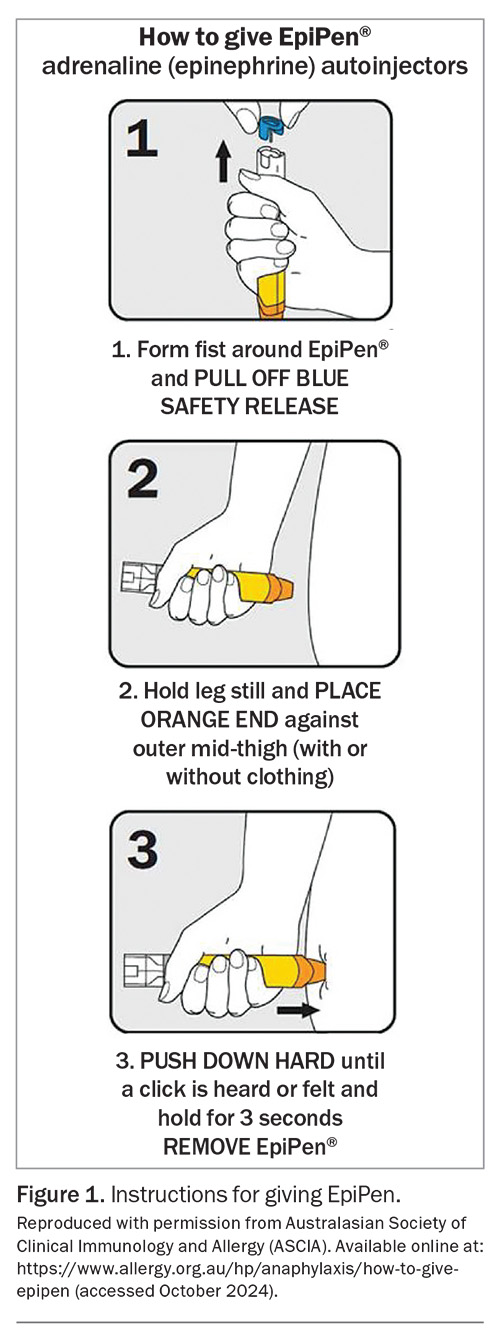

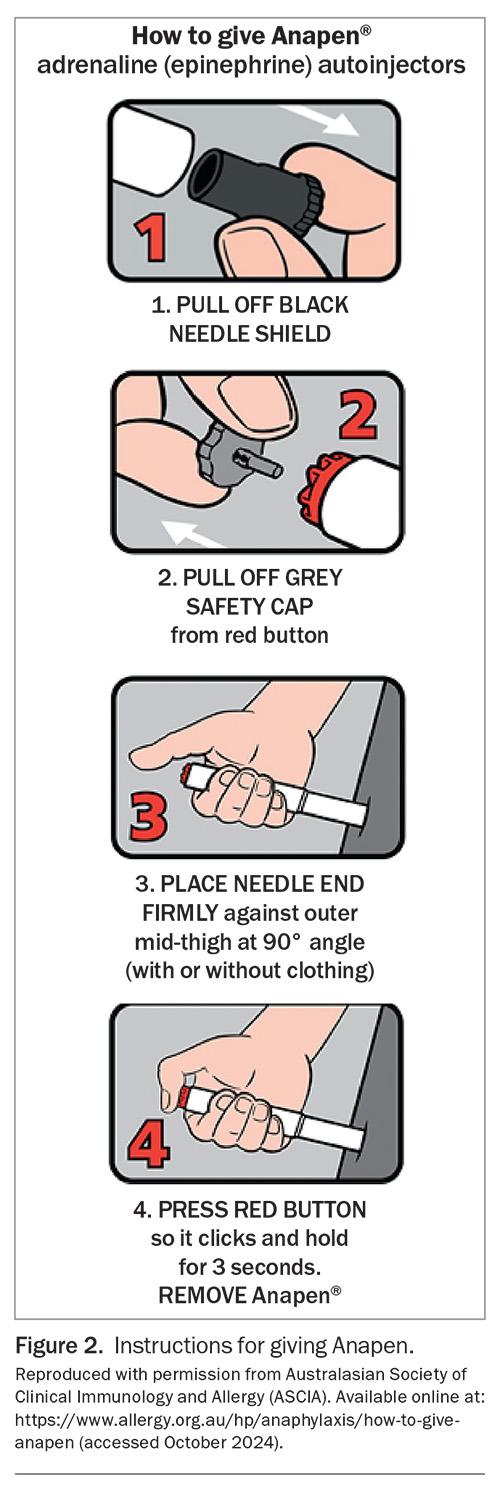

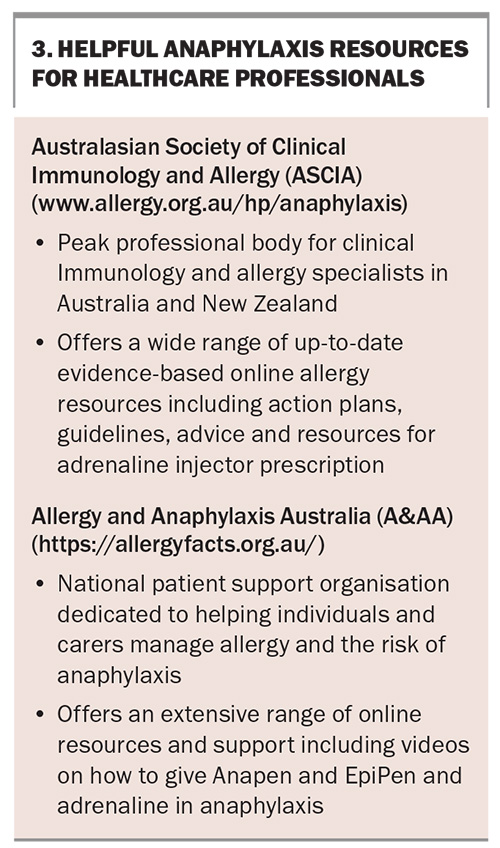

Instructions on how to administer adrenaline with EpiPen and Anapen are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. Instructions and videos are also available on the websites of ASCIA (https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/anaphylaxis#aj2) and the patient support organisation Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia (https://allergyfacts.org.au).

Prescribing adrenaline devices

Adrenaline devices are available in Australia on PBS authority prescription, and an initial prescription is indicated for the anticipated treatment of anaphylaxis. These can be prescribed by a clinical immunologist or allergy specialist, paediatrician or respiratory physician, or by a doctor or nurse practitioner if the patient has been discharged from the hospital or an emergency department after treatment with adrenaline for anaphylaxis. Owing to different legislations, emergency physicians in NSW are unable to prescribe adrenaline devices on authority prescription, but it is recommended that the patient is provided with at least one adrenaline device by the hospital pharmacy on discharge.

Sometimes, patients who have had a clear episode of anaphylaxis do not receive adrenaline in the emergency department for a range of reasons, including failure to present, symptom improvement by the time they arrive in the emergency department or failure of the treating staff to recognise anaphylaxis. In these cases, GPs (and emergency department medical officers) can contact an on-call hospital clinical immunology or allergy specialist to discuss authorisation for an initial adrenaline device prescription, as the PBS criteria state that the patient ‘must have been assessed to be at significant risk of anaphylaxis by, or in consultation with, a clinical immunologist or allergy specialist’. This can prevent a possible excessive delay for adrenaline device prescription, given the potentially long wait time to see a clinical immunology or allergy specialist or other medical specialist.

Patients are eligible for up to two adrenaline devices per prescription with no repeats. Continuing PBS supply for anticipated treatment of anaphylaxis can be prescribed by a doctor or nurse practitioner if the patient has previously been issued with an authority prescription and their devices have been used or expired. It is important to specify the brand and tick the ‘no substitution’ box on a PBS prescription to ensure the brand is not substituted. Adrenaline devices are also available without prescription at a nonsubsidised cost.

Prescribing an adrenaline device alone is not enough to manage patients at risk of anaphylaxis. It is important that individuals are carefully assessed to identify the cause and responsible agent(s), to provide education on allergen avoidance where this applies, to provide education on the recognition of anaphylaxis and device use and to encourage patients and families to practise regularly with a training device. Training devices can be reused and are available from Allergy & Anaphylaxis Australia and some pharmacies. An appropriate ASCIA Action Plan for Anaphylaxis should always be provided with an adrenaline device (https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/anaphylaxis/ascia-action-plan-for-anaphylaxis).

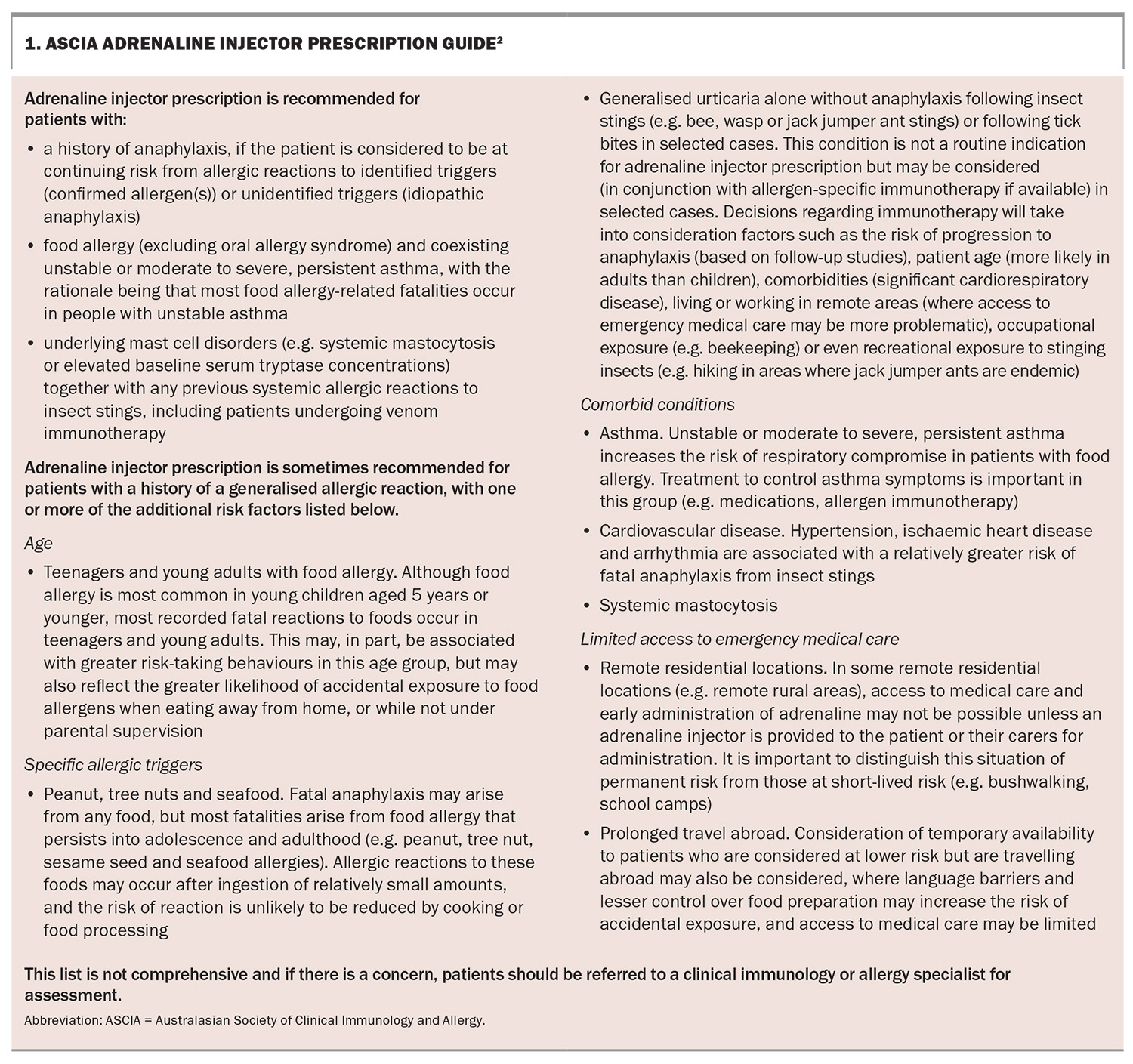

The ASCIA adrenaline injector prescription guide is presented in Box 1.

Adrenaline dose

The optimal dose of adrenaline to treat anaphylaxis is not known.5-7 Current recommendations are based on limited pharmacokinetic studies in healthy people but are supported by decades of clinical practice.1,3-7

In line with international guidelines, ASCIA recommends an adrenaline dose of 0.01 mg/kg (maximum 0.5 mg) to treat anaphylaxis (Table 2).1,3,4 IM adrenaline should be given at a dose of 0.01 mL/kg of a 1:1000 (1 mg/mL) solution, as this gives acceptable volumes for IM injection. For adrenaline IM injection, ASCIA recommends:

- a 150 mcg device for patients weighing between 7.5 and 20 kg

- a 300 mcg device for patients weighing between 20 and 50 kg

- a 300 mcg or 500 mcg device for patients weighing 50 kg or more.

ASCIA’s weight recommendations differ from those in the Australian Product Information for both the Anapen and EpiPen. In 2021, ASCIA revised the lower limit of its weight recommendation for the 150 mcg device from 10 kg to 7.5 kg, based on the following rationale.

- The change aimed to reduce potential underdosing and provide adrenaline device options for infants weighing less than 10 kg. Food allergy is prevalent in this age group, and prescribing adrenaline to those at risk of anaphylaxis is challenging.7,12 Currently, a 100 mcg device is not available in Australia. The options are either to provide an ampoule of adrenaline with a sterile syringe or prefilled syringe, or to prescribe a 150 mcg device.

- Although the use of a 150 mcg device delivers double the recommended 0.01 mg/kg dose in an infant weighing 7.5 kg, IM adrenaline has a good safety profile and is generally well tolerated.7,14,16

- Providing a syringe and ampoule of adrenaline to parents is strongly discouraged as it increases the risk of significant dosing errors (as high as 40-fold in one study) and leads to delays in administration.17

- Providing a prefilled syringe of adrenaline also has disadvantages, as a method to prevent the plunger being depressed is not easy to achieve, and the syringe needs to be refilled regularly, as adrenaline is only stable in a syringe for up to three months.7

The recommended dose of adrenaline for adults weighing 50 kg or more is 500 mcg.1-4 Although either a 300 mcg or 500 mcg device can be used in teenagers and adults, a 500 mcg device gives a higher maximum concentration of adrenaline. A person weighing 50 kg would receive almost 50% less than the recommended dose with a 300 mcg device.6,7 Adrenaline generally reaches its peak concentration five to 10 minutes after injection by adrenaline devices; therefore, if anaphylaxis symptoms persist at five minutes, a second dose is recommended.2,3,5,6

Concerns have also been raised about the potential for subcutaneous injection with adrenaline devices in people with a greater skin-to-muscle distance. Although larger head-to-head studies of devices are needed, a recent systematic review concluded that the device-dependent injection force and speed may be more important than needle length in determining adrenaline pharmacokinetics, and that the time to peak adrenaline concentration was generally longer in people with a greater skin-to-muscle distance, although the overall bioavailability was similar.6,18

Adrenaline device complications

Adrenaline devices are generally safe. Potential injuries related to device use include injection into a digit, lacerations, embedded needles and bone injury.7,19 Training can reduce the risk of device-related complications, and redesign of devices over the years has aimed to reduce the risk of injury. Lacerations requiring sutures have been reported in children after device use.19 The risk of laceration can be reduced by holding the device in place on the thigh before activating it, and securely holding the child to immobilise the leg and reduce movement.7,19 Although bone injury is a theoretical risk, particularly in infants and children with a shorter skin-to-bone distance, no confirmed bone injuries caused by adrenaline devices have been reported.7,19,20 Bunching the skin before injection may help reduce the risk of bone injury.7

How to store an adrenaline injector device

Adrenaline devices should be stored in a readily available location, in a cool and dark place at room temperature (15 to 25°C). They should not be kept in a locked cupboard or refrigerated, as temperatures below 15°C may damage the injector mechanism. People at risk of anaphylaxis should always have their adrenaline device with them. An insulated wallet is recommended if a person carrying a device is outside for an extended time, as studies have shown that after even 12 hours in a car on a warm day, the concentration of adrenaline in a device can reduce by up to 14%.21

Conclusion

Prescribing an adrenaline device is an essential part of the management of anaphylaxis. One device, Anapen, can provide a higher adrenaline dose (500 mcg) for people who weigh 50 kg or more. Practice points on adrenaline devices are summarised in Box 2 and helpful online resources on anaphylaxis for healthcare professionals are listed in Box 3. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Frith has received payment for an educational video on anaphylaxis from Arterial Education. Ms Smith reports that ASCIA receives unrestricted educational grants from sponsors for the ASCIA Annual Conference and to assist ASCIA to develop and update online resources; content is not influenced by sponsors. Professor Katelaris has received payment for participation in a round table discussion on anaphylaxis and adrenaline devices.

References

1. Shaker MS, Wallace DV, Golden DBK, et al. Anaphylaxis-a 2020 practice parameter update, systematic review, and grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020; 145: 1082-1123.

2. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). ASCIA guidelines - acute management of anaphylaxis. Sydney: ASCIA; 2024. Available online at: https://allergy.org.au/hp/papers/acute-management-of-anaphylaxis-guidelines/ (accessed October 2024).

3. Cardona V, Ansotegui IJ, Ebisawa M, et al. World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidance 2020. World Allergy Organ J 2020; 13: 100472.

4. Muraro A, Worm M, Alviani C, et al. EAACI guidelines: anaphylaxis (2021 update). Allergy 2022; 77: 357-377.

5. Dreborg S, Kim H. The pharmacokinetics of epinephrine/adrenaline autoinjectors. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2021; 17: 25.

6. Turner PJ, Muraro A, Roberts G. Pharmacokinetics of adrenaline autoinjectors. Clin Exp Allergy 2022; 52: 18-28.

7. Brown JC. Epinephrine, auto-injectors, and anaphylaxis: challenges of dose, depth, and device. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018; 121: 53-60.

8. Simons FE, Gu X, Simons KJ. Epinephrine absorption in adults: intramuscular versus subcutaneous injection. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 108: 871-873.

9. Lieberman JA, Oppenheimer J, Hernandez-Trujilli VP, Blaiss MS. Innovations in the treatment of anaphylaxis: a review of recent data. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2023; 131: 185-193.

10. European Medicines Agency (EMA). Eurneffy. Amsterdam: EMA; 2024. Available online at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/eurneffy (accessed October 2024).

11. Stafford A, Patel N, Turner PJ. Anaphylaxis-moving beyond severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021; 148: 83-85.

12. Anagnostou A, Sharma V, Herbert L, Turner PJ. Fatal food anaphylaxis: distinguishing fact from fiction. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 10: 11-17.

13. Turner PJ, Campbell DE, Motosue MS, Campbell RL. Global trends in anaphylaxis epidemiology and clinical implications. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8: 1169-1176.

14. Anagnostou K, Turner PJ. Myths, facts and controversies in the diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis. Arch Dis Child 2019; 104: 83-90.

15. Mullins RJ, Wainstein BK, Barnes EH, Liew WK, Campbell DE. Increases in anaphylaxis fatalities in Australia 1997 to 2013. Clin Exp Allergy 2016; 46: 1099-1110.

16. Campbell RL, Bellolio MF, Knutson BD, et al. Epinephrine in anaphylaxis: higher risk of cardiovascular complications and overdose after administration of intravenous bolus epinephrine compared with intramuscular epinephrine. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015; 3: 76-80.

17. Simons FE, Chan ES, Gu X, Simons KJ. Epinephrine for the out-of-hospital (first-aid) treatment of anaphylaxis in infants: is the ampule/syringe/needle method practical? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001; 108: 1040-1044.

18. Duvauchelle T, Robert P, Donazzolo Y, et al. Bioavailability and cardiovascular effects of adrenaline administered by anapen autoinjector in healthy volunteers. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6: 1257-1263.

19. Brown JC, Tuuri RE, Akhter S, et al. Lacerations and embedded needles caused by epinephrine autoinjector use in children. Ann Emerg Med 2016; 67: 307-315.e8.

20. Ibrahim M, Kim H. Unintentional injection to the bone with a pediatric epinephrine auto-injector. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol 2018; 14: 32.

21. Lacwik P, Bialas AJ, Wielanek M, et al. Single, short-time exposure to heat in a car during sunny day can decrease epinephrine concentration in autoinjectors: a real-life pilot study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019; 7: 1362-1364.