IgE-mediated food allergies in infants and children: an update on prevention and management

Food allergies are common and on the rise in Australia, particularly among infants and children. In case of anaphylaxis, adrenaline autoinjectors can be prescribed, with device-specific education and training. Allergen avoidance, assessment and management of the anaphylaxis risk and implementation of a shared care model with specialist input are the mainstays of treatment, but there are promising therapeutic options on the horizon.

Correction

A correction for this article is published in the May 2024 issue of Medicine Today and is available here. The online version and the full text PDF of this article (see link above) have been corrected.

- The prevalence of food allergy continues to rise with common triggers being cow’s milk, egg, peanut, tree nuts, fish, shellfish, soy, sesame and wheat.

- There is the potential for children to outgrow food allergies, although the age of resolution is variable and difficult to predict, depending on the allergenic food trigger.

- Early introduction and regular ingestion of allergenic foods reduces the risk of developing food allergies.

- Many conditions (e.g. rashes, eczema) may be mistaken for food allergies, but these should be managed appropriately with treatments other than food avoidance.

- Risk factors for severe anaphylaxis include the presence of poorly controlled asthma, allergy to multiple food triggers, a persisting allergy and advanced age.

- If an adrenaline autoinjector is prescribed for a patient at risk of anaphylaxis, an allergy action plan, anaphylaxis education and first aid training are essential and should be provided routinely.

- Immunotherapy and biologics are promising future treatments for the management of immunoglobulin E-mediated food allergies.

Food allergy in infants and children is common and an increasingly major public health concern. Thus, there is growing need for improved prevention and management strategies beyond the current principles of allergen avoidance of the culprit foods and education on managing acute reactions, including anaphylaxis. This article discusses immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated food allergy in infants and children, as well as strategies for its prevention and management.

Definition of food allergy

A food allergy arises from an aberrant and inappropriate immune response to a usually harmless substance (allergen) contained within a triggering food. The most common and well-recognised type of food allergy is IgE-mediated food allergy, although other food allergic disorders characterised by different immune mechanisms exist (e.g. non-IgE-mediated disorders, and mixed IgE- and non-IgE-mediated disorders).

Epidemiology and aetiology of food allergy

The prevalence of food allergy is highest in infants and young children, reported between 8% and 17% globally.1-3 In Australia, around one in 10 infants (up to 12 months of age) and one in 20 children (up to 4 years of age) are affected.3 It is unclear why food allergies occur or why there has been a marked increase in food allergies over the past few decades. They are commonly thought to be secondary to complex interactions between genetics and the environment. Several predisposing factors have been implicated, including:

- a strong family history of atopy (at least two affected family members)4

- comorbid eczema5

- initial exposure to food via a non-gastrointestinal route (e.g. epicutaneous)

- delayed oral introduction to foods

- early antibiotic exposure in the neonatal period

- vitamin D deficiency

- a lack of diversity in the gut microbiome.

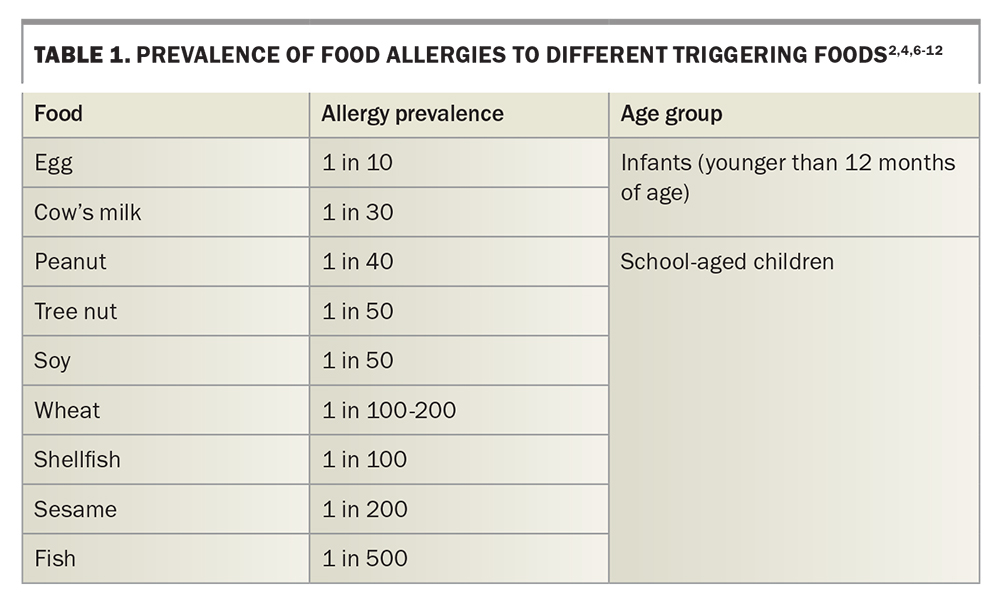

Common culprit foods include cow’s milk, egg, soy, wheat, sesame, peanuts, tree nuts, fish and shellfish (Table 1).2,4,6-12 Cow’s milk and egg allergies tend to develop early in infancy, which especially contributes to the disproportionately high prevalence in this age group. However, most children with cow’s milk and egg allergies tend to outgrow their allergies by school age (variable rates reported between 50 and 90%).3,6,13-16 Nut and shellfish allergies commonly develop during school age and tend to persist into adulthood, with about 20% of children outgrowing their allergy by 16 years of age.3,7,8 The rate of food-related anaphylaxis hospital admissions has also been increasing in Australia, although the rate of fatalities remains unchanged.17

Pathophysiology and clinical features of IgE-mediated food allergy

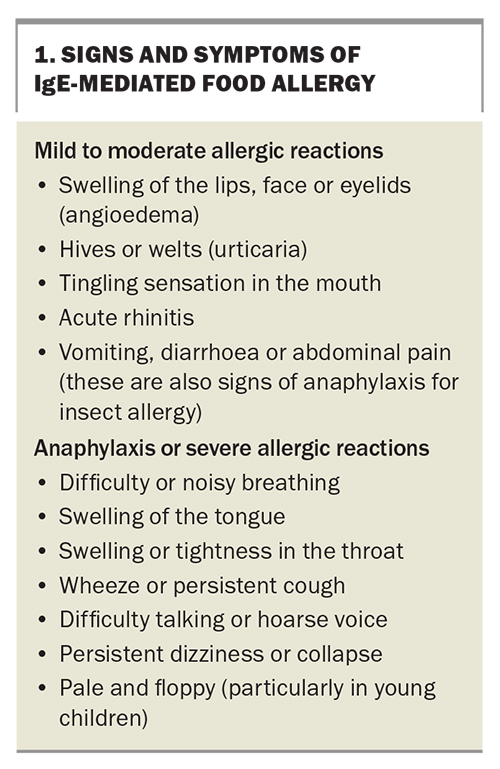

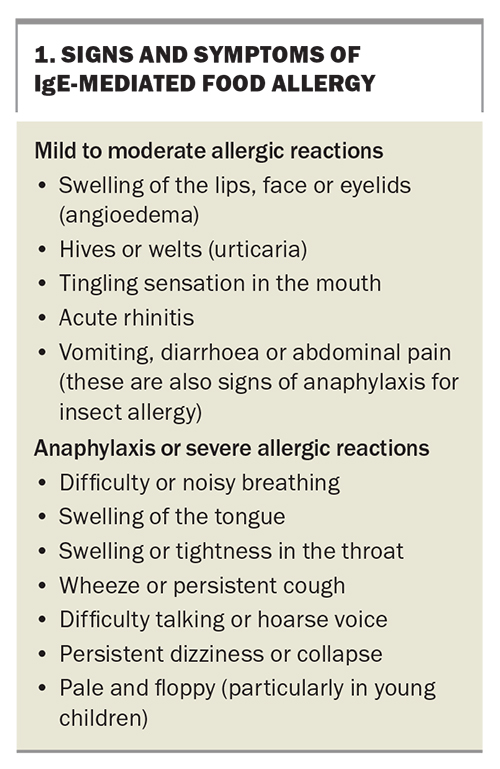

In individuals with allergies, sensitisation arises from an initial exposure to a food allergen that stimulates the production of specific IgE antibodies by plasma cells. These IgE antibodies bind to tissue-residing mast cells and circulating basophils. In the process of immediate hypersensitivity, on re-exposure to the allergenic food, circulating allergens bind to and crosslink the surface IgE molecules on these mast cells and basophils, causing a cascade of signals that lead to immune activation, degranulation and the release of mediators (e.g. histamine, leukotrienes and prostaglandin). These mediators can act systemically on various tissues, including the skin, gastrointestinal mucosa, airway smooth muscle and endothelium, giving rise to the clinical manifestations of an allergic reaction (Box 1).

Symptoms can develop quickly, generally within the first 30 minutes of exposure, and can occur on first oral ingestion of the culprit food (which is likely secondary to initial sensitisation via a cutaneous exposure). Most allergic reactions are mild. Cutaneous symptoms of pruritus, urticaria and angioedema (particularly of the face) are common and, although can appear alarming, are considered symptoms of mild to moderate allergic reactions. Gastrointestinal symptoms of nausea, abdominal pain and diarrhoea can also occur in mild to moderate allergic reactions.

Signs of severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) include respiratory and cardiovascular involvement (Box 1). Clinical manifestations may include one or more of the following: difficulty breathing, tongue swelling, throat tightness, wheezing, a persistent cough, a hoarse voice, loss of consciousness, pallor or floppiness (particularly in young children, resulting from hypotension). It is difficult to predict whether a reaction may result in anaphylaxis. Certain cofactors associated with (but not predictive of) the risk of developing anaphylaxis include:18

- poorly controlled asthma

- advanced age

- prior history of severe reactions

- upright posture

- exercise

- the amount of food ingested and, for some foods, how it is prepared (raw or lightly cooked vs well cooked).

Currently, no tests are available to help accurately predict the risk of anaphylaxis.

Older children with allergic rhinitis may develop oral allergy syndrome, also known as pollen food allergy syndrome, which is IgE-mediated and arises from allergen cross-reactivity between common pollens and certain fruits and vegetables. The clinical manifestations are usually mild; localised to symptoms of itching and irritation of the lips, mouth and throat; and do not evolve into anaphylaxis. These can be managed conservatively with food avoidance or eating cooked forms of the culprit foods (which are usually well tolerated).

Cutaneous contact with food particles may result in symptoms of local irritation but these do not cause anaphylaxis. Parents often worry about their child smelling peanut butter, but as an oily substance, the protein in peanut butter does not aerosolise, and the smell does not cause anaphylaxis.19

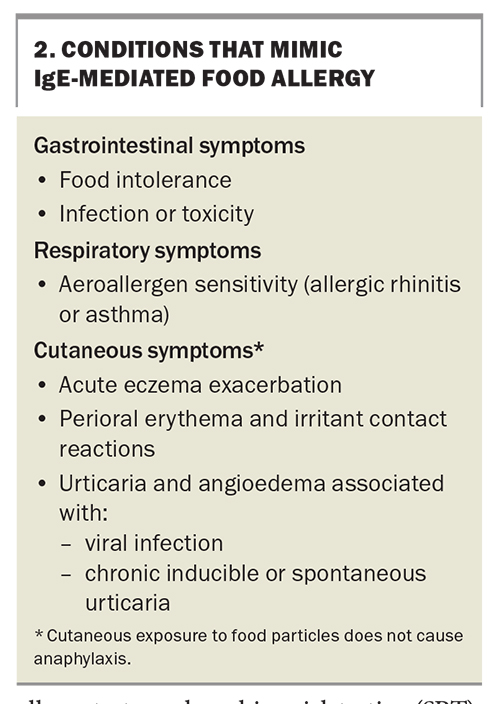

Conditions that are confused with food allergy

Most cases of IgE-mediated food allergy are recognisable, although many other conditions can be misdiagnosed as food allergy and inappropriately managed with food avoidance (Box 2). Rashes are common presentations in infants and children, and parents are often referred to an allergist because of concerns of IgE-mediated food allergy. Most presentations with rashes are not secondary to food allergy, and instead, are caused by other conditions, such as infection, inducible or spontaneous urticaria, perioral erythema and skin irritant contact reactions. Perioral contact dermatitis is common in babies and is not a food allergy.

Parents frequently report flares of eczema in children with the ingestion of certain foods and, although this is a recognised phenomenon, the symptoms are usually delayed (hours to days), are not primarily IgE-mediated and are not related to a risk of anaphylaxis. The mainstay of treatment is to manage the child’s underlying atopic dermatitis with regular use of a moisturiser and appropriate use of topical corticosteroids. Food elimination is generally not recommended to manage eczema, as prolonged avoidance of foods is a risk factor for the development of true IgE-mediated food allergy on re-exposure.

Diagnosis and investigation of IgE-mediated food allergy

In the evaluation of a patient with suspected IgE-mediated food allergy, a detailed clinical history is paramount. The roles of allergy tests, such as skin prick testing (SPT), and in vitro tests, such as serum-specific IgE (ssIgE) testing, are ancillary and must be guided by and interpreted in the context of the patient’s specific clinical history.

Characteristic features on history taking that suggest an IgE-mediated food allergy include an immediate or rapid onset of symptoms associated with food ingestion, and reproducibility of the symptoms on exposure to the same culprit food. It is essential to elucidate whether symptoms of anaphylaxis are present (Box 1). A thorough history of the events and dietary intake preceding the reaction is useful, but the suspected culprit food may not always be apparent, and in settings outside the home (e.g. childcare centres, schools and restaurants), collateral history may need to be obtained. It is also useful to consider food packaging labels as an additional source of information when attempting to identify the culprit food.

The nutritional, growth and development statuses of the infant or child must also be evaluated, as there are potential complications of failure to thrive and nutritional deficiency, especially in the context of food allergy to staple foods, such as milk, egg and wheat, or in cases of multiple food allergies. Assessment of early infant feeding including breastfeeding and formula feeding practices, timing of solid food introductions and tolerance of other allergenic foods in the diet provide valuable information when formulating appropriate recommendations for the management of a child’s food allergy.

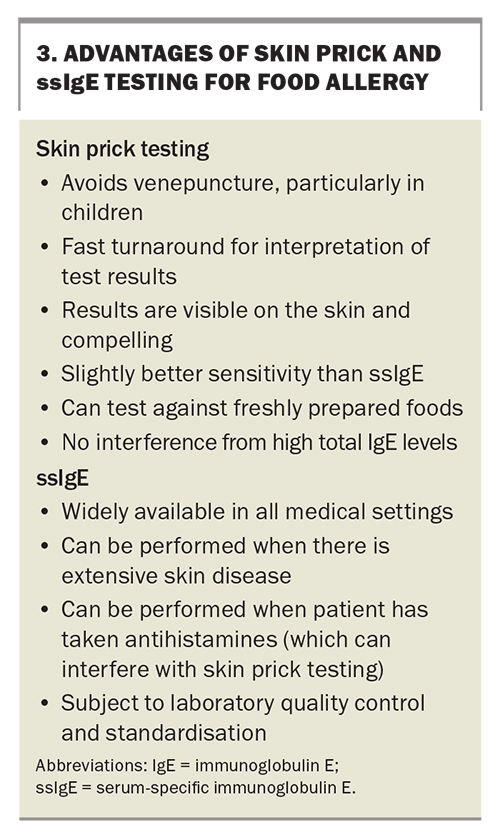

Food allergy tests can be performed to confirm a suspected history of an IgE-mediated food allergy and should not be used in isolation to establish a diagnosis, as a ‘positive’ test result (or sensitisation) may not always indicate the presence of clinical allergy. Thus, if a food is already tolerated in the child’s diet, it should not be removed based on a positive test result alone. SPT and ssIgE testing have their individual advantages (Box 3).

SPT is a useful and safe point-of-care test performed by specialist allergy services. It has high sensitivity but poor specificity and thus is not an ideal screening test given the potential for false-positive results.20 Additionally, higher rates of false-negative results occur in infants younger than 12 months of age, as their skin may be less reactive.

ssIgE testing is more readily available in the primary care setting. It measures food-specific antibodies present in a patient’s serum (expressed in kUA/L). It has comparable sensitivity and specificity to those of SPT and, similarly, should be used judiciously and in consideration of the clinical history.20 Mixed food panel testing should be avoided, as a positive result in a panel may not clearly confirm the culprit food and, instead, may lead to patients avoiding multiple foods unnecessarily. Both SPT and ssIgE testing inform the likelihood of an IgE-mediated food allergy but do not predict the severity of a reaction or risk of anaphylaxis.

Component-resolved diagnostics (CRD) is a newer in vitro assay measuring IgE levels in response to a purified or recombinant allergen found specifically within the food, as opposed to ssIgE testing, which tests against the crude extract of the food and may contain many allergens. The benefits of CRD have yet to be fully validated, and it is a costly test and hence not implemented routinely in practice. Screening tests with CRD panels are not recommended.

The gold-standard test for IgE-mediated food allergy is the oral food challenge (OFC). Indications for performing OFCs include to:

- confirm an initial diagnosis when a food is highly suspected to have caused a reaction, but allergy testing may be equivocal or negative

- allow for the expansion of a diet when several foods are under suspicion based on the clinical history or positive allergy test results

- evaluate foods that were removed from the diet or not introduced at all based primarily on positive allergy test results

- assess the resolution of a food allergy.

Because of the risk of reactions, OFCs must always be performed by experienced clinicians in a medically supervised setting with resuscitation equipment readily available.

Lastly, healthcare professionals must be wary of the multitude of unproven and nonevidence-based methods of allergy testing (e.g. kinesiology, iridology, Vega testing, IgG food antibody testing), which can result in adverse outcomes, such as dangerous dietary restrictions, delayed access to appropriate testing and treatment and negative psychological impacts (e.g. anxiety and disordered eating).21

Preventing food allergies

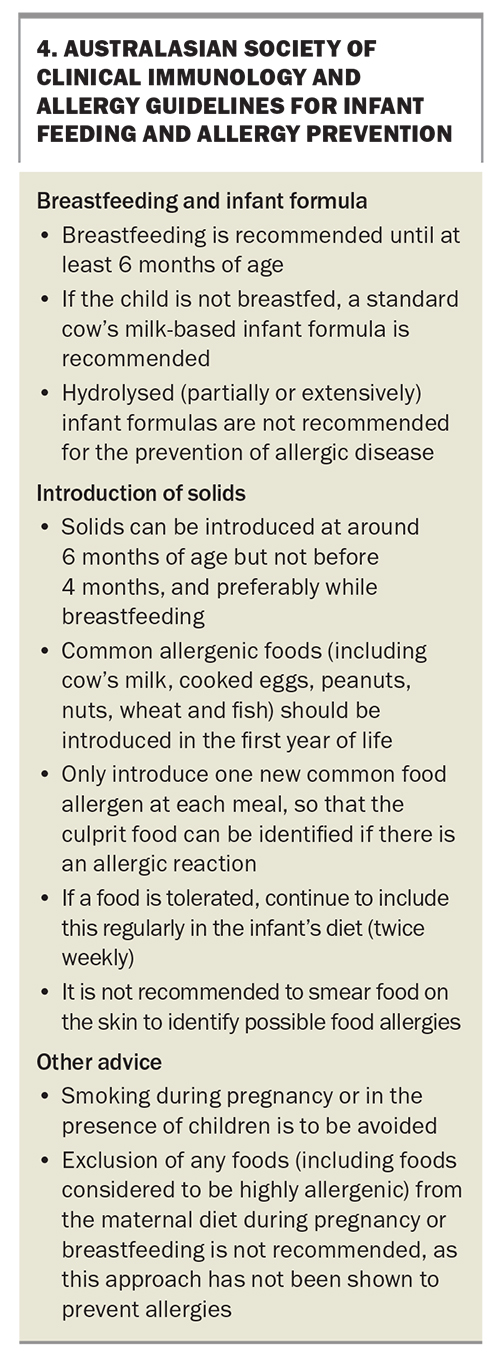

Within the past decade, there has been a paradigm shift towards the recommendation of earlier introduction and subsequent regular ingestion of common allergenic foods in infants’ diets to prevent IgE-mediated food allergies. Several observational studies and randomised controlled trials have examined this approach, with the strongest evidence suggesting the early introduction of peanut and well-cooked egg has a relative risk reduction of about 80% in infants at high risk of developing food allergies.22-24 Based on this emerging evidence, the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy devised consensus guidelines for infant feeding and allergy prevention (Box 4).25,26 To date, there are no reported cases of fatality following peanut ingestion among infants younger than 1 year of age.

In recent years, several commercially available food protein powders have been marketed for early allergen introduction in infants for the purpose of allergy prevention. These products often contain combinations of different food proteins, tailored for the convenience of exposure to multiple allergenic foods simultaneously. However, these are not usually recommended in Australia, as the protein content and proportion of each allergenic food may not be well-defined, and if an allergic reaction occurs, it is then difficult to identify the probable culprit.

Management of IgE-mediated food allergy

Principles of management

A shared-care model is recommended for the management of IgE-mediated food allergy in infants and young children. The main principles of management are to:

- identify the culprit food causing the allergy

- educate the patient or parent on allergen avoidance

- assess the risk for anaphylaxis, or presence of previous anaphylaxis, and provide patients with an appropriate safety net, allergy anaphylaxis action plan and adrenaline autoinjector.

When to refer

Referral to a specialist for IgE-mediated food allergy assessment should be sought for children who have a history of suspected anaphylaxis; children who are at an increased risk of anaphylaxis (e.g. comorbid asthma); infants and very young children when there are important implications for growth, development and nutrition; infants and children in whom the diagnosis or suspected food is uncertain; and children who have multiple food allergies.

Dietary management

Avoidance of the culprit food is the mainstay of treatment. Infants and young children are at particular risk of failure to thrive and nutritional deficiency, particularly if staple foods are avoided; thus, they should be monitored closely with specialist support and advice from a dietitian. Some children with cow’s milk and egg allergies can tolerate these foods in baked goods, and if regularly consumed, may lead to faster resolution of the allergy.27-29 However, if the child has not consumed baked cow’s milk or egg previously, this approach should only be considered under specialist medical advice.

Supportive management of anaphylaxis and adrenaline autoinjector prescribing

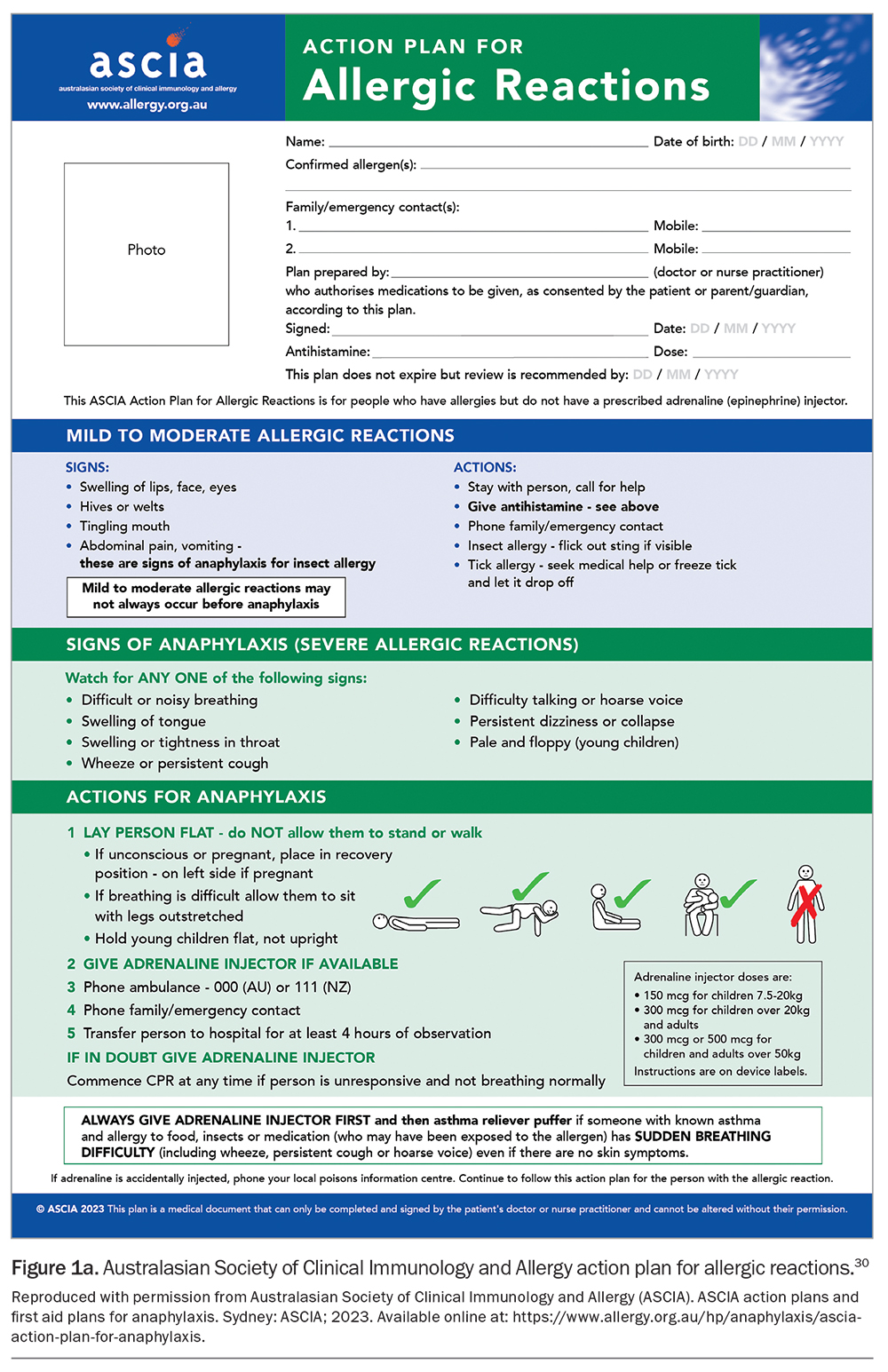

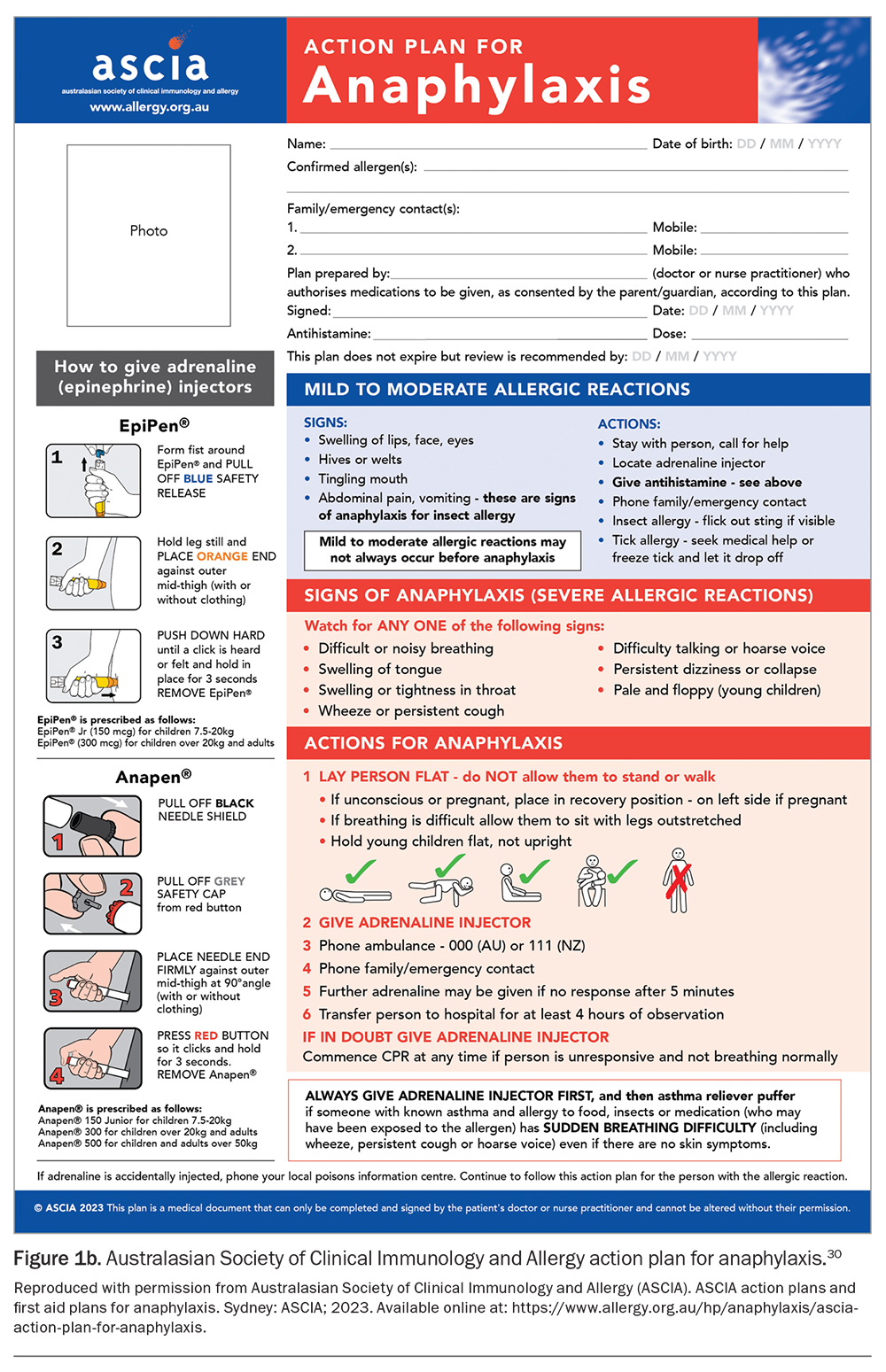

For children at risk of anaphylaxis, adrenaline autoinjectors are prescribed and anaphylaxis action plans are provided, along with routine patient education (Figure 1a and Figure 1b).30 The principles of anaphylaxis education include teaching parents and patients about:

- recognising signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis

- understanding that adrenaline is the first-line treatment for anaphylaxis

- how to use an adrenaline autoinjector (with practical advice and practice) and phoning an ambulance immediately afterwards

- remembering to always carry or have ready access in different situations to an in-date adrenaline autoinjector and an anaphylaxis action plan (e.g. at school, on holidays or while travelling).

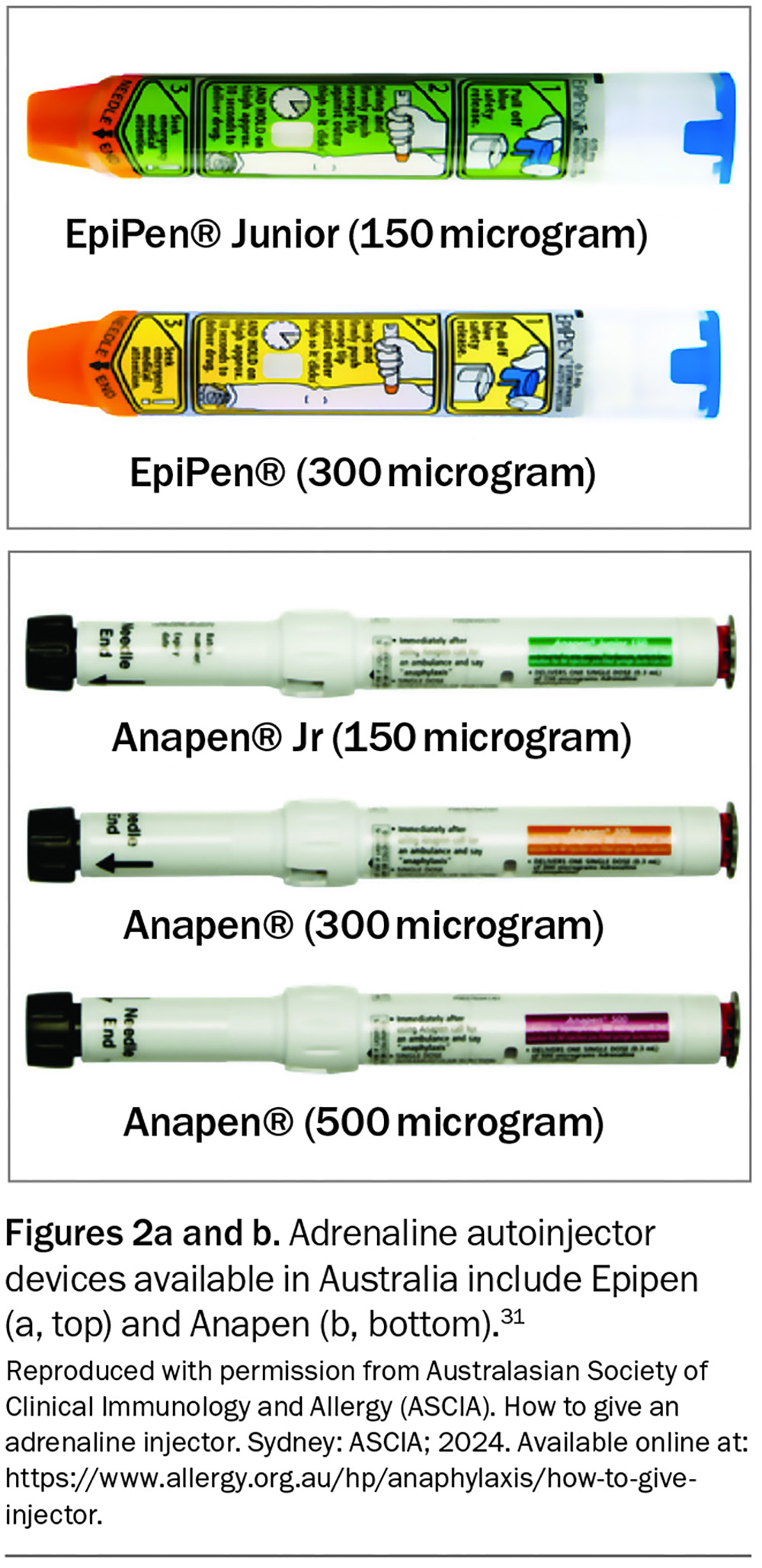

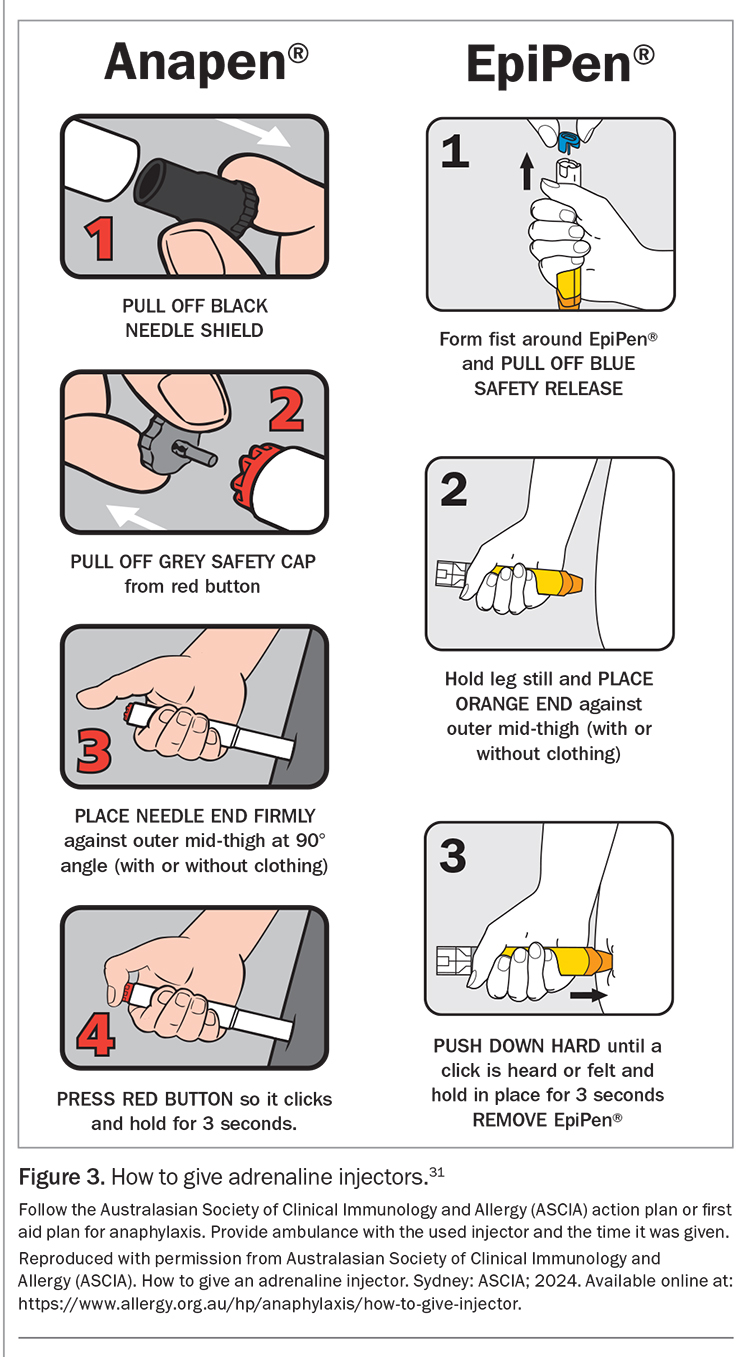

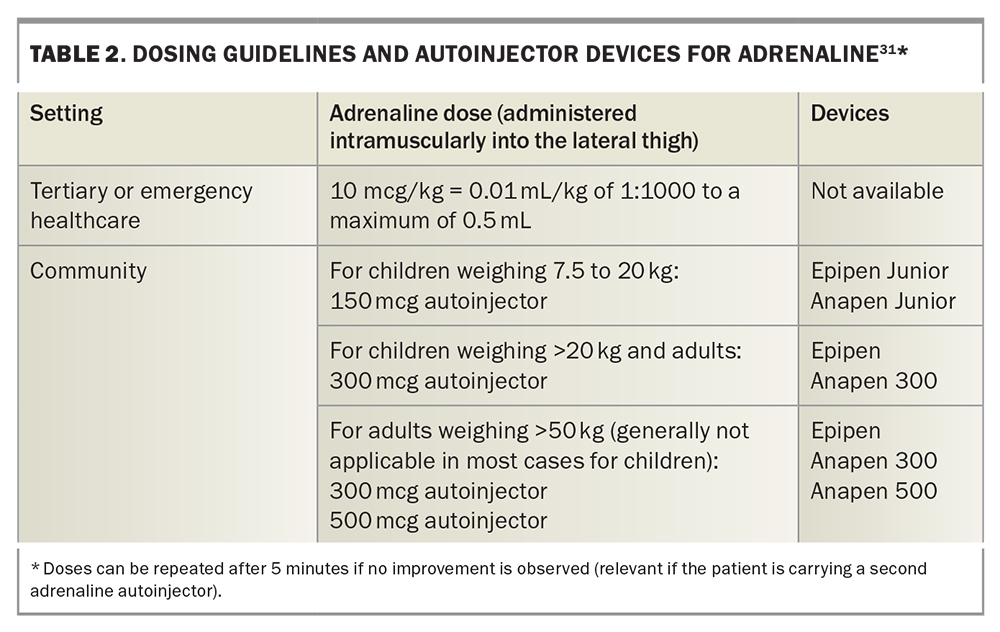

An initial authority PBS prescription of adrenaline autoinjectors (quantity of two) can only be given by an allergy and immunology specialist or by an emergency doctor when patients are discharged from the hospital with a first episode of anaphylaxis. Two devices are available in Australia: Epipen and Anapen (Figures 2a and b).31 Education and training specific to the device prescribed should be provided. Instructions on the use of each adrenaline autoinjector are shown in Figure 3.31 GPs can prescribe adrenaline autoinjectors for continuing treatment, as listed on the PBS (dosing guidelines are presented in Table 2), and maintain current anaphylaxis action plans.31 Action plans do not expire; however, they should be reviewed regularly by a clinician or nurse practitioner.

Shared care model for people with an allergy

The shared care project was introduced in 2023 and is funded by the Australian Government after a scoping project conducted by the National Allergy Strategy in 2019. The project aims to improve access to care for people with an allergy. A key component is to provide better support, education and specialist access for GPs who remain welcome to provide input.

Future treatments

There continues to be abundant research on the role of immunotherapy in reducing the burden of food allergy (noting that immunotherapy is not curative). The primary aims of immunotherapy are desensitisation (i.e. ability to tolerate the allergen during treatment) and potentially sustained unresponsiveness (i.e. ability to tolerate the allergen after discontinuing immunotherapy). There is emerging evidence that oral immunotherapy may be effective for desensitisation, specifically for peanut, egg and cow’s milk allergies, with only the peanut allergen showing the potential for sustained unresponsiveness thus far, particularly in infants and young children.32,33 Other routes of administration (sublingual, epicutaneous, subcutaneous and intradermal) are being investigated. Most studies reveal frequent mild to moderate reactions and, thus, the safety of immunotherapy is not yet validated. The decision to undertake oral immunotherapy off-label outside a clinical trial must be preceded by a discussion regarding the risks and benefits and documented informed consent by the parent or guardian. The treatment must then be administered strictly under close supervision of an experienced clinical immunologist or allergist who has the benefit of regular peer review. A proven diagnosis of food allergy must be made before starting therapy and should not be based solely on the presence of specific IgE antibody levels. Carers and children (if age appropriate) should understand that this is potentially a lifelong undertaking. Unpublished methods with unproven outcomes and the lack of adequate carer education around managing anaphylaxis are potential problems and should be flagged with patients and carers before oral immunotherapy is commenced.

There is an increasing interest in biologics, especially omalizumab (anti-IgE monoclonal antibody), as a therapeutic option for food allergy, either in combination with immunotherapy or alone.32,34,35 Too few studies have been published to draw conclusions on the efficacy of biologics and the drugs are expensive; however, they are becoming a promising area of research for IgE-mediated food allergy treatment. A peptide vaccine for peanut allergy is also in clinical trials.36

Conclusion

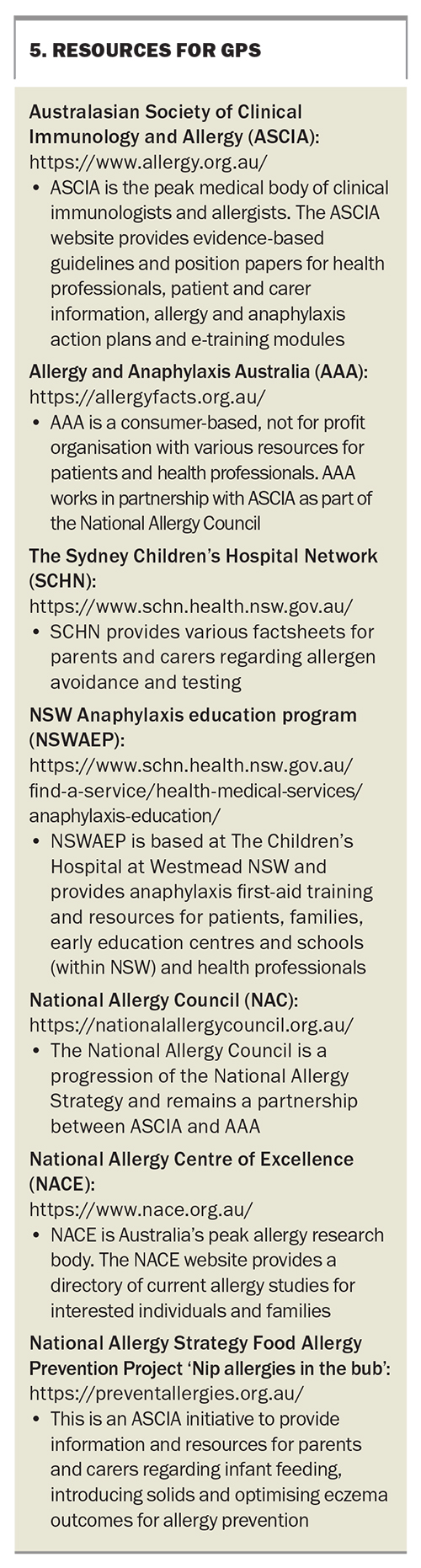

Rates of food allergy among infants and children in Australia are at an unprecedented high. Although extremely rare, there is the potential risk of severe and fatal anaphylaxis among individuals with food allergies; thus, patients and their parents or carers must remain vigilant during management. Additionally, there is a significant disease burden on health-related quality of life, which is important for clinicians to address. These issues are increasingly and frequently seen in primary care settings and, thus, it is vital for healthcare providers to remain well-informed of current evidence-based practice to support patients with food allergies and their parents and families. Allergen avoidance, assessment and management of the anaphylaxis risk and implementation of a shared care model with specialist input are the mainstays of treatment, but there are promising therapeutic options on the horizon. Some useful resources for GPs are presented in Box 5. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Gupta RS, Springston EE, Warrier MR, et al. The prevalence, severity, and distribution of childhood food allergy in the United States. Pediatrics 2011; 128: e9-e17.

2. Osborne NJ, Koplin JJ, Martin PE, et al. Prevalence of challenge-proven IgE-mediated food allergy using population-based sampling and predetermined challenge criteria in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 127: 668-676.e2.

3. Peters RL, Koplin JJ, Gurrin LC, et al. The prevalence of food allergy and other allergic diseases in early childhood in a population-based study: HealthNuts age 4-year follow-up. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140: 145-153.e8.

4. Koplin J, Allen K, Gurrin L, et al. The impact of family history of allergy on risk of food allergy: a population-based study of infants. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013; 10: 5364-5377.

5. Skjerven HO, Lie A, Vettukattil R, et al. Early food intervention and skin emollients to prevent food allergy in young children (PreventADALL): a factorial, multicentre, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2022; 399: 2398-2411.

6. Høst A. Frequency of cow’s milk allergy in childhood. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2002; 89: 33-37.

7. Peters RL, Guarnieri I, Tang MLK, et al. The natural history of peanut and egg allergy in children up to age 6 years in the HealthNuts population-based longitudinal study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 150: 657-665.e13.

8. McWilliam VL, Perrett KP, Dang T, Peters RL. Prevalence and natural history of tree nut allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2020; 124: 466-472.

9. Savage JH, Kaeding AJ, Matsui EC, Wood RA. The natural history of soy allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 125: 683-686.

10. Ricci G, Andreozzi L, Cipriani F, Giannetti A, Gallucci M, Caffarelli C. Wheat allergy in children: a comprehensive update. Medicina 2019; 55: 400.

11. Xepapadaki P, Christopoulou G, Stavroulakis G, et al. Natural history of IgE-mediated fish allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9: 3147-3156.e5.

12. Giannetti A, Pession A, Bettini I, Ricci G, Giannì G, Caffarelli C. IgE mediated shellfish allergy in children—a review. Nutrients 2023; 15: 3112.

13. Schoemaker AA, Sprikkelman AB, Grimshaw KE, et al. Incidence and natural history of challenge‐proven cow’s milk allergy in European children – EuroPrevall birth cohort. Allergy 2015; 70: 963-972.

14. Sicherer SH, Warren CM, Dant C, Gupta RS, Nadeau KC. Food allergy from infancy through adulthood. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020; 8: 1854-1864.

15. Wood RA, Sicherer SH, Vickery BP, et al. The natural history of milk allergy in an observational cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131: 805-812.e4.

16. Xepapadaki P, Fiocchi A, Grabenhenrich L, et al. Incidence and natural history of hen’s egg allergy in the first 2 years of life—the EuroPrevall birth cohort study. Allergy 2016; 71: 350-357.

17. Mullins RJ, Dear KBG, Tang MLK. Changes in Australian food anaphylaxis admission rates following introduction of updated allergy prevention guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2022; 150: 140-145.e1.

18. Turner PJ, Arasi S, Ballmer‐Weber B, et al. Risk factors for severe reactions in food allergy: rapid evidence review with meta‐analysis. Allergy 2022; 77: 2634-2652.

19. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Peanut allergy: emerging concepts and approaches for an apparent epidemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120: 491-503.

20. Soares‐Weiser K, Takwoingi Y, Panesar SS, et al. The diagnosis of food allergy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Allergy 2014; 69: 76-86.

21. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). Allergy testing. Sydney: ASCIA; 2020. Available online at: https://www.allergy.org.au/patients/allergy-testing/allergy-testing (accessed February 2024).

22. De Silva D, Halken S, Singh C, et al.; European Academy of Allergy, Clinical Immunology Food Allergy, Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group. Preventing food allergy in infancy and childhood: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2020; 31: 813-826.

23. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 803-813.

24. Perkin MR, Logan K, Marrs T, et al. Enquiring About Tolerance (EAT) study: feasibility of an early allergenic food introduction regimen. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137: 1477-1486.e8.

25. Joshi PA, Smith J, Vale S, Campbell DE. The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy infant feeding for allergy prevention guidelines. Med J Aust 2019; 210: 89-93.

26. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). ASCIA guidelines - infant feeding and allergy prevention. Sydney: ASCIA; 2020. Available from: https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/papers/infant-feeding-and-allergy-prevention (accessed February 2024).

27. Leonard SA, Sampson HA, Sicherer SH, et al. Dietary baked egg accelerates resolution of egg allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012; 130: 473-480.e1.

28. Leonard SA, Caubet JC, Kim JS, Groetch M, Nowak-Węgrzyn A. Baked milk- and egg-containing diet in the management of milk and egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015; 3: 13-23.

29. Mehr S, Turner PJ, Joshi P, Wong M, Campbell DE. Safety and clinical predictors of reacting to extensively heated cow’s milk challenge in cow’s milk-allergic children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014; 113: 425-429.

30. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). ASCIA action plans and first aid plans for anaphylaxis. Sydney: ASCIA; 2023. Available online at: https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/anaphylaxis/ascia-action-plan-for-anaphylaxis (accessed February 2024).

31. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). How to give an adrenaline injector. Sydney: ASCIA; 2024. Available online at: https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/anaphylaxis/how-to-give-injector (accessed February 2024).

32. De Silva D, Rodríguez Del Río P, De Jong NW, et al. Allergen immunotherapy and/or biologicals for IgE‐mediated food allergy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Allergy 2022; 77: 1852-1862.

33. Soller L, Carr S, Kapur S, et al. Real-world peanut OIT in infants may be safer than non-infant preschool OIT and equally effective. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022; 10: 1113-1116.e1.

34. Fiocchi A, Vickery BP, Wood RA. The use of biologics in food allergy. Clin Experimental Allergy 2021; 51: 1006-1018.

35. Worm M, Francuzik W, Dölle-Bierke S, Alexiou A. Use of biologics in food allergy management. Allergol Select 2021; 5: 103-107.

36. Voskamp AL, Khosa S, Phan T, et al. Phase 1 trial supports safety and mechanism of action of peptide immunotherapy for peanut allergy. Allergy 2024; 79: 485-498.