Heavy menstrual bleeding: understanding the impact and treatment options

This clinical case review describes a 36-year-old woman who presents with heavy menstrual bleeding and need for more reliable contraception. The assessment of this patient and her management options, including oral treatments and use of the levonorgestrel intrauterine device, are discussed.

- Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is the most common presentation of abnormal uterine bleeding, affecting one in four women of reproductive age, yet it remains under-recognised and undertreated.

- The initial assessment includes thorough history-taking, assessment of impact on quality of life, physical examination and exclusion of pregnancy, iron deficiency and anaemia. Further investigations are based on the initial assessment.

- Oral HMB treatment can be offered at first presentation, including when a woman is undergoing further investigation or waiting for other treatment.

- The most effective medical management for HMB remains the 52 mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. This also offers reliable contraception.

- Patients should be referred for early specialist review if there is suspicion of malignancy or other significant pathology based on clinical assessment or ultrasound.

Case scenario

Heather is a 36-year-old woman who consults with you for advice about heavy menstrual periods and to discuss her contraceptive needs. She initially had normal menstrual periods but over the past decade she has had worsening heavy and painful periods, which have been partially controlled with use of the combined oral contraceptive pill. She has two children and has decided that she has completed her family. She occasionally has difficulty remembering to take her contraceptive pill and so is looking for a more reliable, longer-term solution for contraception. Heather’s periods last for five days and are particularly heavy on the first two days, during which time she passes clots and needs to change her tampons every two hours or so, in addition to using sanitary pads. She has recently seen another GP at your practice for fatigue and was found to have mild iron deficiency anaemia. She has no personal or family history of a bleeding disorder. Heather’s pelvic ultrasound shows a small fibroid but is otherwise normal.

Commentary

Heather requires management of heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) and dysmenorrhoea, as well as reliable contraception, which is a common scenario in general practice.

HMB is defined as excessive menstrual blood loss that significantly impacts a woman’s physical, emotional, social and material quality of life.1,2 Thus, quantification of the blood lost is not needed to diagnose a woman with HMB, as it is essentially based on quality of life.

What are normal menstrual cycle parameters?

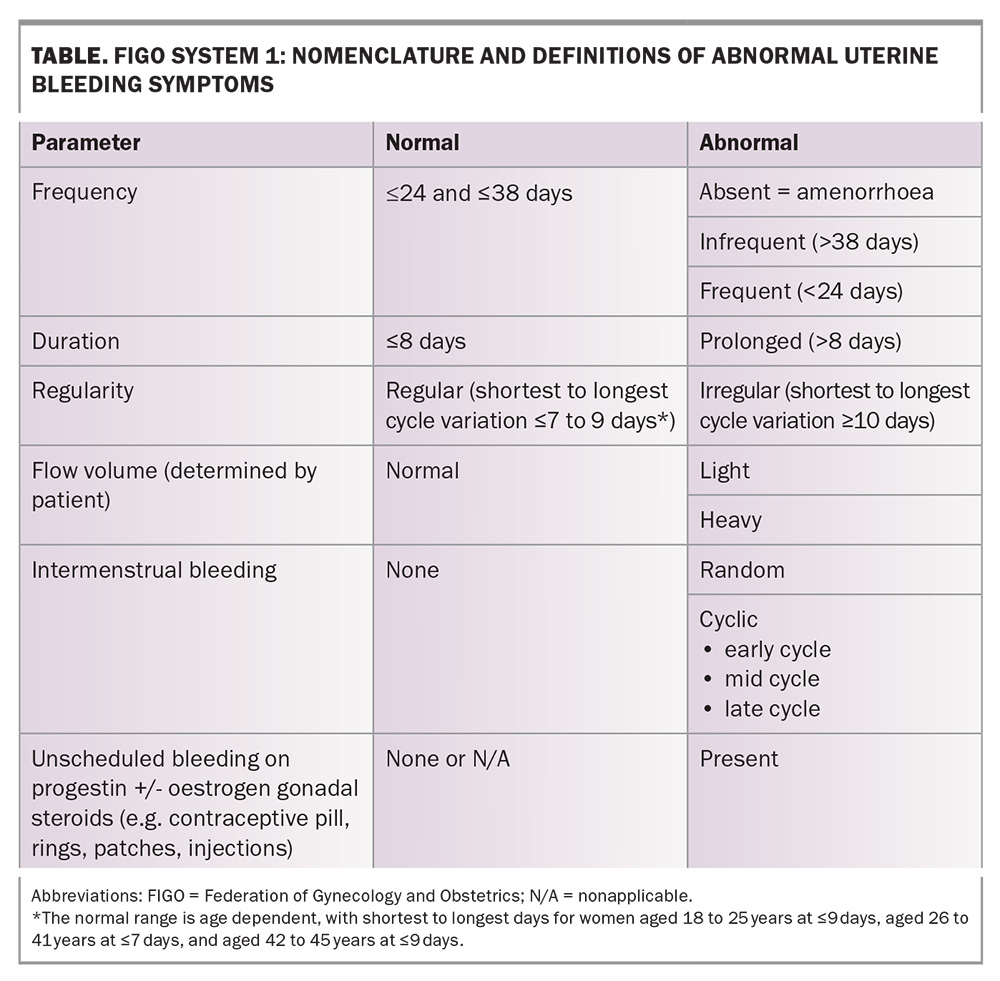

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system 1 for nomenclature of symptoms of normal and abnormal uterine bleeding is shown in the Table. This uses four primary descriptors of frequency, duration, regularity and subjective flow volume, which are based on the previous six months (in the absence of pregnancy or puerperium).

HMB is the most common presentation of abnormal uterine bleeding, affecting one in four women of reproductive age, yet it remains under-recognised and undertreated. This is largely because of the normalisation of symptoms by patients, healthcare providers and society. At least 50% of women with HMB are yet to see a healthcare professional. In addition, societal taboos and lack of awareness often prevent open discussions and timely care. Financial constraints and the tendency of women to prioritise other people’s needs over their own further contribute to the problem.3

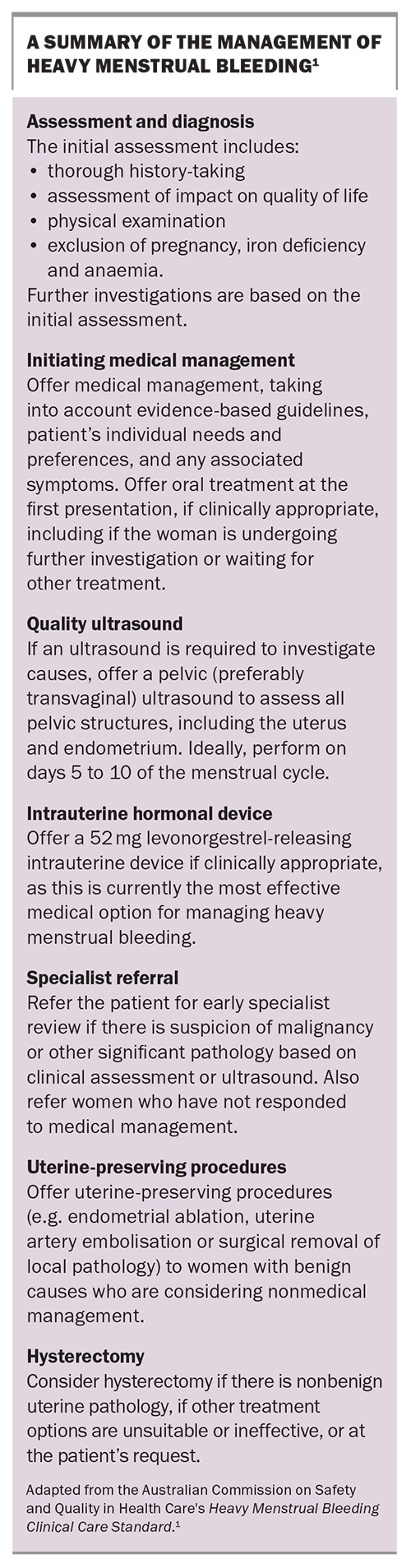

Half of women with HMB have associated pelvic pain, which in Heather’s case presents as dysmenorrhoea. The combined oral contraceptive pill has provided some relief, but Heather’s adherence issues and need for a more effective treatment option for HMB suggest that the 52 mg levonorgestrel intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) could be a better option for her. This method is highly effective for both contraception and managing HMB, addressing multiple concerns for Heather. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care has recently published updated national HMB standards, emphasising the spectrum of treatment options available to women with HMB and advising to offer less invasive treatments first if suitable (see the Box for a summary of the HMB Clinical Care Standard).1,2

Assessment and diagnosis

The assessment of a woman with HMB includes thorough history-taking, including consideration of the following:

- What is the impact on quality of life?

- What is the length of the period?

- Are there clots and, if so, are they larger than a 50c coin?

- Is the patient using two or more forms of sanitary protection?

- Is the patient waking up at night to change the sanitary protection?

- Is the patient changing sanitary protection more than two-hourly?

- Is flooding through clothes occurring?

- Are there symptoms of exhaustion or fatigue?

- Is there associated pelvic pain or symptoms such as pressure?

- Is there a desire for fertility?

To identify any palpable mass or abnormal uterine size, Heather’s examination, with consent, includes a speculum examination and a bimanual pelvic examination. To assess for iron deficiency and anaemia routinely measure serum ferritin levels and perform a full blood count. Rule out pregnancy with a urine beta human chorionic gonadotropin test.

Testing for coagulation disorders (e.g. von Willebrand’s disease) should be considered for women who have had HMB since their periods started and/or have a personal or family history suggesting a coagulation disorder. This is not the case for Heather as she initially had normal periods. There is also no role for female hormone testing in this situation because she does not desire fertility or have any symptoms suggestive of premature ovarian insufficiency. The pelvic ultrasound (preferably transvaginal) is ideally performed on days 5 to 10 of her menstrual cycle because the endometrial lining is thinnest during this time and, therefore, it is easier to identify uterine polyps and fibroids.

Management

If clinically appropriate, oral HMB treatment should be offered at first presentation, including when a woman is undergoing further investigation or waiting for other treatment. Encourage patients to leave the consultation with a clear management plan, with an alternative treatment option in case the first treatment is not effective or has adverse side effects.4

In Heather’s case, she could consider an antifibrinolytic agent, such as tranexamic acid, which is prescribed as 1 g four times per day for up to four days when menstruation has started. The dose may be increased to a maximum of 4.5 g daily. In addition, she could also use oral NSAIDs (mefenamic acid 500 mg three times daily or naproxen 500 mg twice daily), which can decrease the menstrual flow if taken regularly during menstruation. NSAIDs reduce the effects of prostaglandins, which are elevated in women with excessive menstrual bleeding, and should also help with dysmenorrhoea. However, this is not a contraceptive arrangement.2,4

The most effective medical management for HMB remains the 52 mg LNG-IUD, which is a clinically appropriate solution even in the context of a small uterine fibroid.1,5 The duration of use of the LNG-IUD for contraception has recently been extended by the TGA from five to eight years. For the indication of HMB, if symptoms have not returned after five years of use, the LNG-IUD can be continued for up to eight years as well. For other noncontraceptive reasons (such as endometrial protection during menopausal hormone therapy) the duration of use remains unchanged at up to five years. The 52 mg LNG-IUD is listed on the PBS for contraception and idiopathic HMB in a patient in whom oral treatments are ineffective or contraindicated.

In Australia, over one in four pregnancies are unintended. Half of these pregnancies occur in women using contraception at the time of conception. The 52 mg LNG-IUD will offer Heather an effective contraceptive option (>99% effective) as well as proactive HMB management.

Heather would have merited an early gynaecology review if there had been any suspicion of malignancy or other significant pathology (such as large fibroids) based on clinical assessment or ultrasound. Specialist referral is also offered to a woman who has not responded to medical management.

If suitable, Heather can also be offered nonmedical, less invasive, uterine‑preserving procedures (e.g. endometrial ablation, uterine artery embolisation or surgical removal of local pathology, including polyps or fibroids).

In general, a hysterectomy for the management of HMB can be considered if:

- there is nonbenign uterine pathology

- other treatment options are ineffective or are unsuitable

- there are significant pressure symptoms (e.g. large fibroids, back pain, secondary urinary symptoms)

- it is the patient’s preference.

Heather’s outcome

Heather decides to try the 52 mg LNG-IUD, which you insert during a subsequent appointment after appropriate counselling. Over the next few months, Heather has a significant reduction in the heaviness of her menstrual periods and no ongoing adverse effects. You recommend that she returns to see you in just under five years’ time to check for any symptoms related to HMB and for consideration of LNG-IUD replacement. She should return sooner if there are any issues.

Summary

Heather’s case exemplifies the most effective medical management of HMB with the added benefit of long-term contraception using the LNG-IUD. This approach offers a reliable solution that addresses both her symptoms and contraception needs and improves her quality of life. GPs can consider the LNG-IUD for patients with similar presentations, ensuring thorough counselling and follow up to monitor efficacy and address any concerns. The 52 mg LNG-IUD can now be used for up to eight years for contraception. For HMB, if symptoms have not returned after five years of use, the LNG-IUD can be continued and then removed or replaced after eight years at the latest. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Uppal is a Bayer media spokesperson for HMB on The Period Perspective Survey, CSL Vifor speaker, Ambassador for Heidi Health and RANZCOG media spokesperson and is part of the Bayer APAC Digital Thought Leader Academy program. She has also received payment from Bayer, Orion, Organon and Besins for GP Education and Implanon trainer sessions.

References

1. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Clinical Care Standard. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2024. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-06/heavy-menstrual-bleeding-clinical-care-standard-2024.pdf (accessed September 2024).

2. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding. NICE Quality Standard 47. London: NICE; 2018 (updated 2021).

3. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding Market Research.Quantitative survey with Australian women aged 35 to 52. Prepared for Hologic. February 2023. Available online at: www.livecomfortably.au (accessed September 2024).

4. Uppal T. How to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. Medical Republic. July 2021. Available online at: https://www.medicalrepublic.com.au/how-to-treat-heavy-menstrual-bleeding/5730 (accessed September 2024).

5. Bofill Rodriguez M, Dias S, Jordan V, et al. Interventions for heavy menstrual bleeding; overview of Cochrane reviews and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022, Issue 5: CD013180.