Medical therapies for ulcerative colitis: a practical update

Ulcerative colitis is an increasingly prevalent inflammatory condition of the bowel that results in abdominal pain, diarrhoea, rectal bleeding and urgency. There are numerous new medications available for treating this chronic condition.

- Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory bowel disease primarily affecting the colon with associated comorbidities, including extraintestinal manifestations of disease, mental health disorders and reduced quality of life.

- Timely and appropriate medical therapy can alter the natural history of the disease and prevent complications of disease, such as motility issues and colorectal cancer.

- About half of all patients with ulcerative colitis respond well to

5-aminosalicylate therapy. - Advanced therapies for ulcerative colitis have various mechanisms of action with very different safety profiles.

- Prednisolone is best used sparingly, with a preference to initiate and optimise treatment with advanced therapies.

- Biologic use in pregnancy is generally safe and often helps achieve good pregnancy outcomes; however, small molecules used for ulcerative colitis may be teratogenic.

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that primarily affects the colon.1 A wide spectrum of disease patterns is seen in ulcerative colitis, varying from mild cases to patients who are refractory to medical therapy and require a colectomy to obtain disease control. Untreated inflammation can lead to significant morbidity, active extraintestinal manifestations of disease, mental health disorders, sexual dysfunction, nutritional abnormalities and the development of complications such as colonic dysmotility and colorectal cancer.1,2

Australia has one of the highest occurrences of ulcerative colitis globally.3 An Australian general practice network study conducted between 2017 and 2019 found a crude prevalence rate of 334 per 100,000 people. This high prevalence, the expenses associated with treatment and the negative effect on young people engaging in study and work contribute to a substantial negative economic impact. In Australia, the estimated economic loss secondary to inflammatory bowel disease was estimated to be more than $3 billion in 2012.4

In recent years, there has been an expanding array of treatment options. This article is a practical primer on the modern medical management of ulcerative colitis.

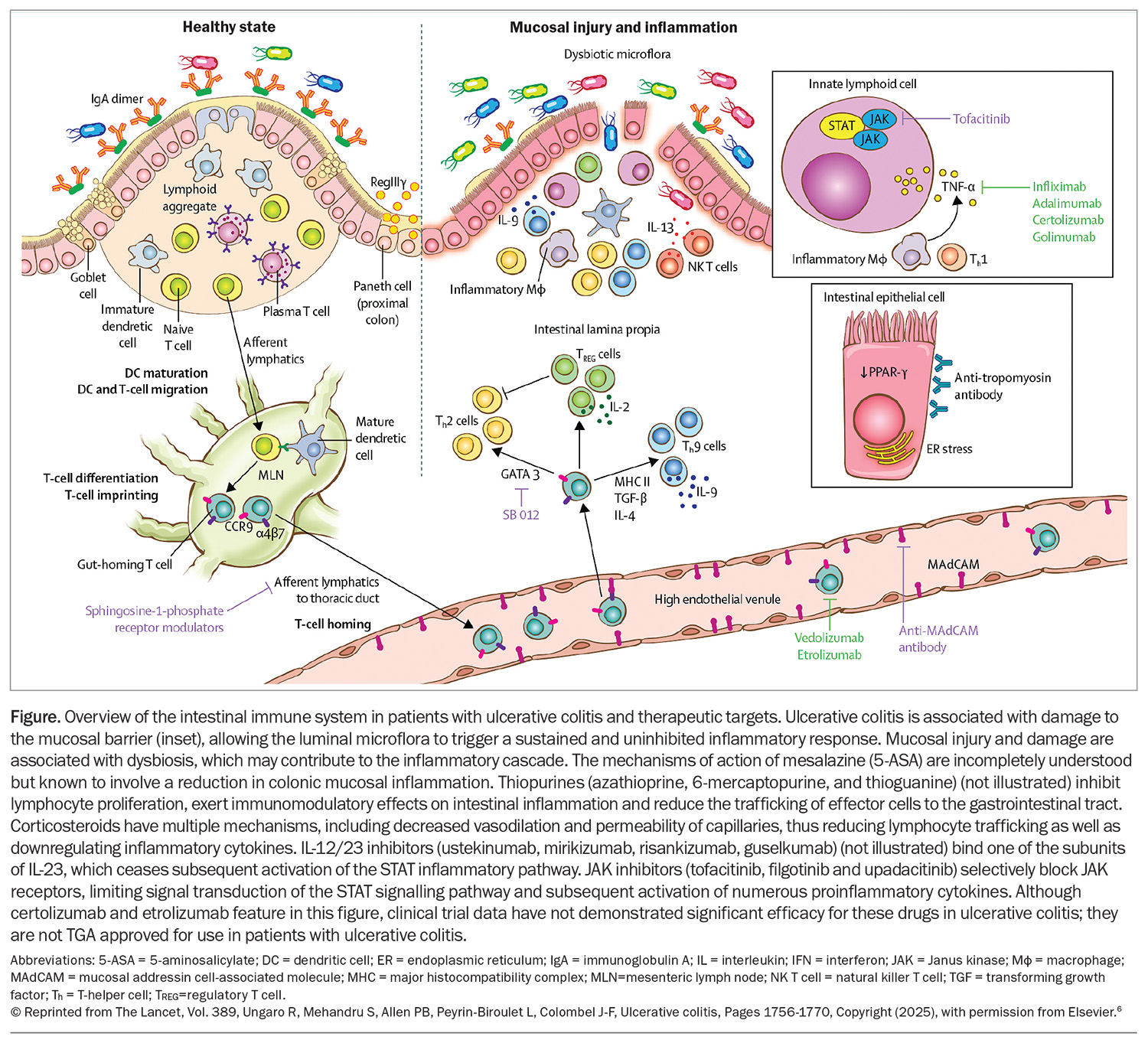

Medical therapy targets

Ulcerative colitis has a complicated and incompletely understood aetiology, with a combination of susceptible genetics, environmental factors (e.g. hygiene hypothesis and Western diet) and gut microbiome abnormalities culminating in immune dysregulation and inflammation of the colonic mucosa.5 Proinflammatory cytokines underpin ongoing inflammation in the bowel (Figure).1,5,6 Severe untreated inflammation can lead to dysmotility, stricturing, dysplasia and colorectal cancer.1,2

Medical therapy targets key mechanisms or cytokines in this inflammatory pathway and subsequently downregulates inflammation. The aims of therapy are to improve symptoms, improve quality of life, normalise markers of inflammation, prevent complications and disease progression and induce healing of the gut wall.7

Therapies for mild to moderate disease

5-aminosalicylates

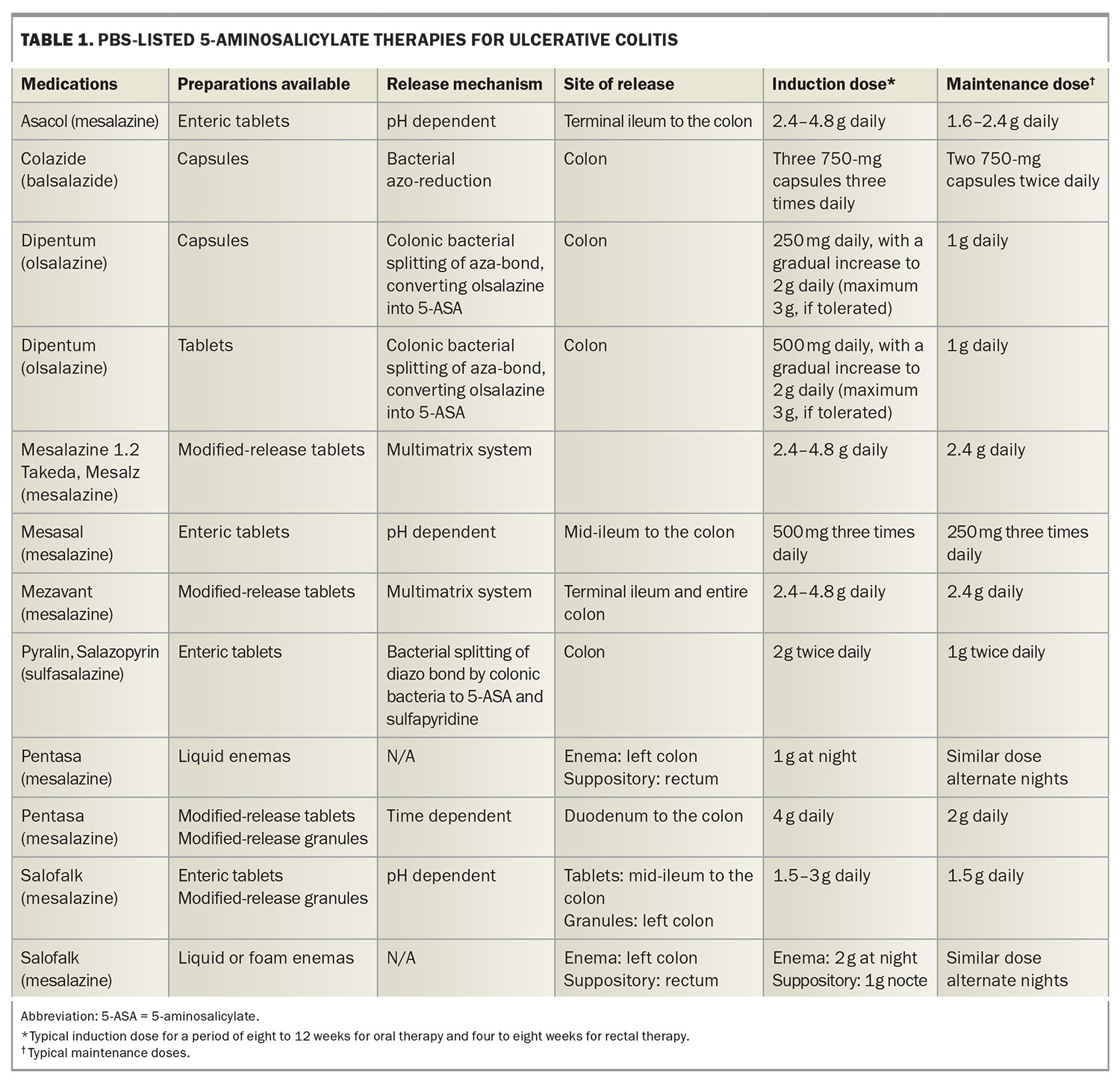

About half of all patients with ulcerative colitis have a mild phenotype,8 which can often be managed effectively with 5-aminosalicylate (5-ASA) therapy. Although the mechanism of action is unclear, 5-ASA therapies work topically, and downregulate colonic inflammation at the mucosal level.9 The two main drugs that comprise 5-ASA therapy are sulfasalazine and mesalazine. Balsalazide (a pro-drug of mesalazine) has also been used historically. Mesalazine contains only 5-ASA, whereas sulfasalazine consists of two components: sulfapyridine and 5-ASA.

Sulfasalazine is initially converted to sulfapyridine and 5-ASA in the colon, where 5-ASA can exert its anti-inflammatory effects locally. Mesalazine delivers 5-ASA directly to the colon. Mesalazine has several advantages over sulfasalazine and is now the primary drug of choice. The benefits include once-daily dosing, as opposed to two to four times daily as required with sulfasalazine. Furthermore, side effects with mesalazine are uncommon, whereas sulfasalazine can cause nausea, vomiting and headaches because of allergies associated with sulfapyridine. Sulfasalazine can cause reversible oligospermia that can be associated with fertility issues.10,11 However, sulfasalazine is more effective for enteropathic arthritis and is often used in patients with concomitant ulcerative colitis and enteropathic arthritis.12

Mesalazine has numerous formulations (Table 1), including oral and topical (per rectal) therapies.13-17 The oral therapies have different mechanisms of release.14 Choosing the appropriate preparation may be important as the timing of release will differ, with some formulations commencing release in the small bowel and others commencing release in the left colon. This may be clinically important as patients with extensive disease may respond better to a pan-colonic preparation, and there is evidence to suggest that patients with distal colitis respond better to granule preparations; however, this is debated.18 The oral formulations have a high dose induction, followed by a lower maintenance dose. Some patients will be prescribed high-dose mesalazine indefinitely as they relapse on low-dose mesalazine.

In addition to oral preparations, rectal topical preparations of mesalazine are available, including suppositories and enemas. The extent of an enema’s action is the sigmoid and perhaps the descending colon, whereas suppositories will only treat the rectum, but are usually more tolerable by patients to self-administer than enemas. The evidence suggests that patients respond better to both ‘top and bottom’ therapy, as oral preparations may not deliver an adequate amount of the drug to the distal colon, as well as the rectum in particular.17 The largest hurdle to rectal therapies is patient reluctance, particularly in the long term. Therefore, a commonly used strategy in clinical practice is to use rectal therapies alongside oral therapies for inducing remission and then tailoring off the rectal therapy as tolerated to maintain disease control. For patients with a proctitis phenotype, suppository therapy is usually more effective than oral therapy and reducing the suppository therapy to three times a week when well can often lead to success in achieving a balance between receiving therapy and the inconvenience of rectal preparations.17

In addition to treating inflammation, evidence suggests that mesalazine has a chemopreventive action against bowel cancer. It is unclear if this chemopreventive effect is secondary to, or independent of, the drug’s ability to treat inflammation.19 This is a favourable benefit, given the increased risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis.

Overall, mesalazine is considered a safe drug and is usually well tolerated.20 Patients are not immunocompromised on these medications. Rare but serious complications can occur including interstitial nephritis and numerous hypersensitivity reactions, such as pancreatitis, pericarditis, myocarditis, pneumonitis, hepatitis and hematological abnormalities. There is a one in 400 risk of developing interstitial nephritis and hence, three-monthly monitoring with a basic blood panel (including a full blood count; liver function tests; C-reactive protein level measurement; and urea, electrolytes and creatinine tests) for the first six months followed by six- to 12-monthly monitoring is recommended.20

In summary, 5-ASA therapies are safe, inexpensive and effective medications for the management of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis.

Thiopurines

Thiopurines, such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine, are small molecules that inhibit lymphocyte proliferation, exert immunomodulatory effects on intestinal inflammation and reduce the trafficking of effector cells to the gastrointestinal tract.21 Thiopurines are used as maintenance therapy in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative colitis after failure to respond to mesalazine or as combination therapy with an antitumour necrosis factor (TNF) agent to prevent antibody formation and improve serum drug levels.17,21

However, the use of thiopurines purely for the treatment of ulcerative colitis is becoming less desirable. Thiopurines have a significant toxicity profile including the cumulative risk of nonmelanomatous skin cancer, urothelial cancer, cervical cancer and lymphoma.22 Advanced therapies are more effective, often better tolerated and, generally speaking, have more attractive safety profiles than thiopurines.17 In addition, the initial monitoring and dose titration for thiopurines can make them more challenging to prescribe. The main barrier to using advanced therapies rather than thiopurines is the substantial cost difference. Patients with ulcerative colitis are eligible for an advanced therapy on the PBS if they have inadequate disease control after three months on a thiopurine (full dose) or if they are intolerant to thiopurines.

Methotrexate

Unlike in Crohn’s disease, methotrexate is not an effective treatment for ulcerative colitis;23 however, methotrexate can be used off label in combination with anti-TNF therapy to prevent antibody formation against anti-TNF therapies. Methotrexate is commonly prescribed for the treatment of numerous extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease, such as enteropathic arthritis.21

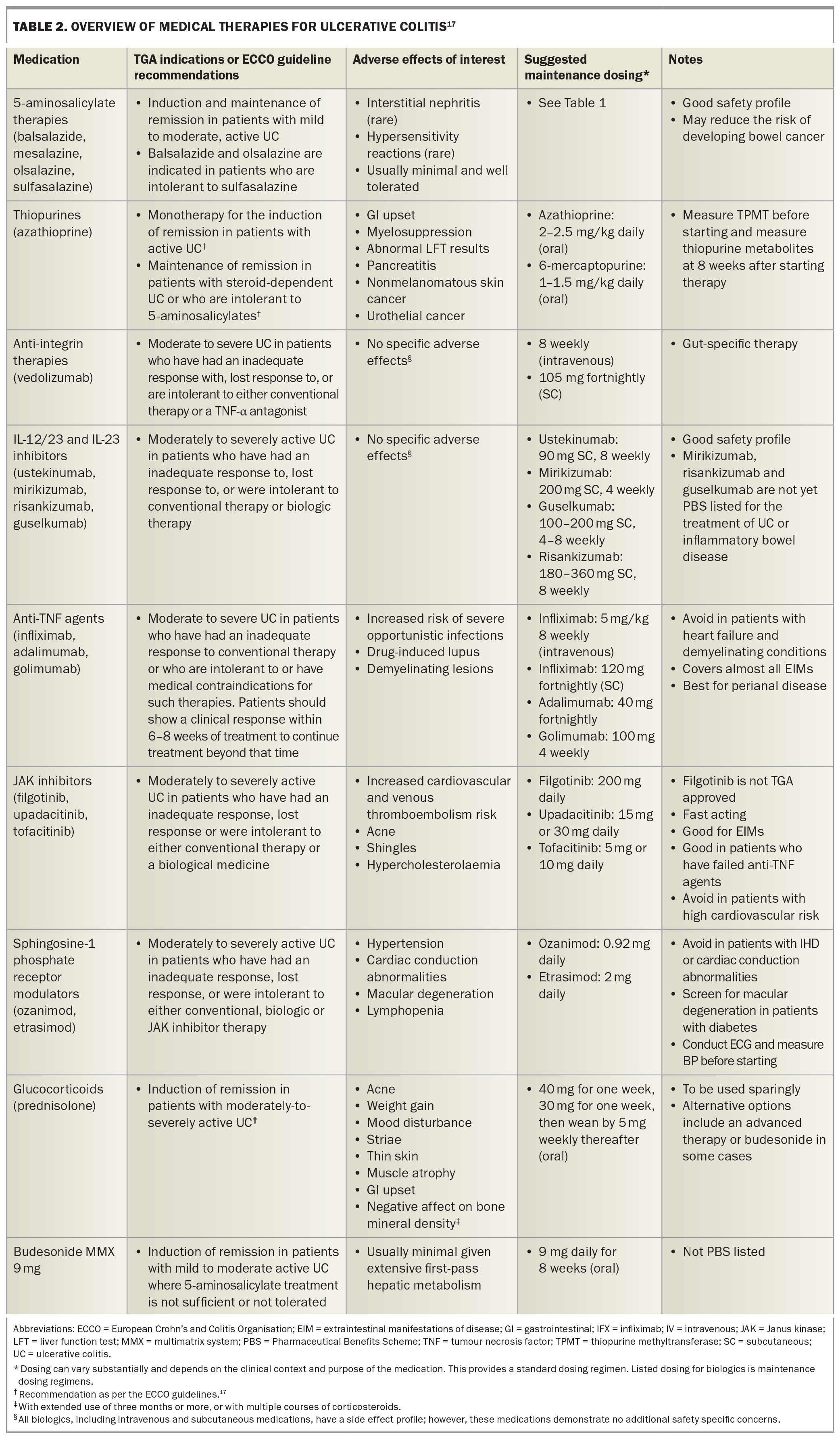

Advanced therapies for moderate to severe disease

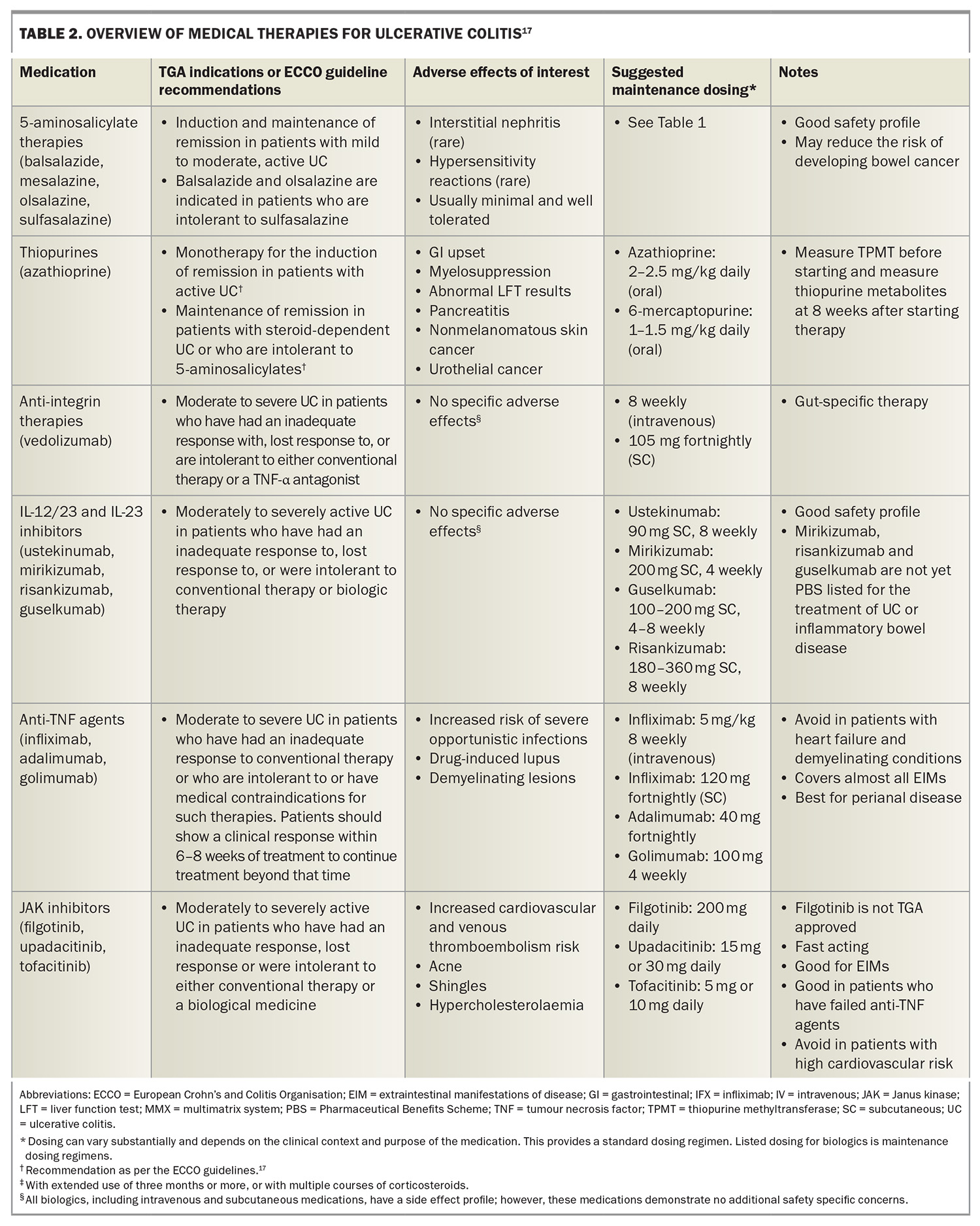

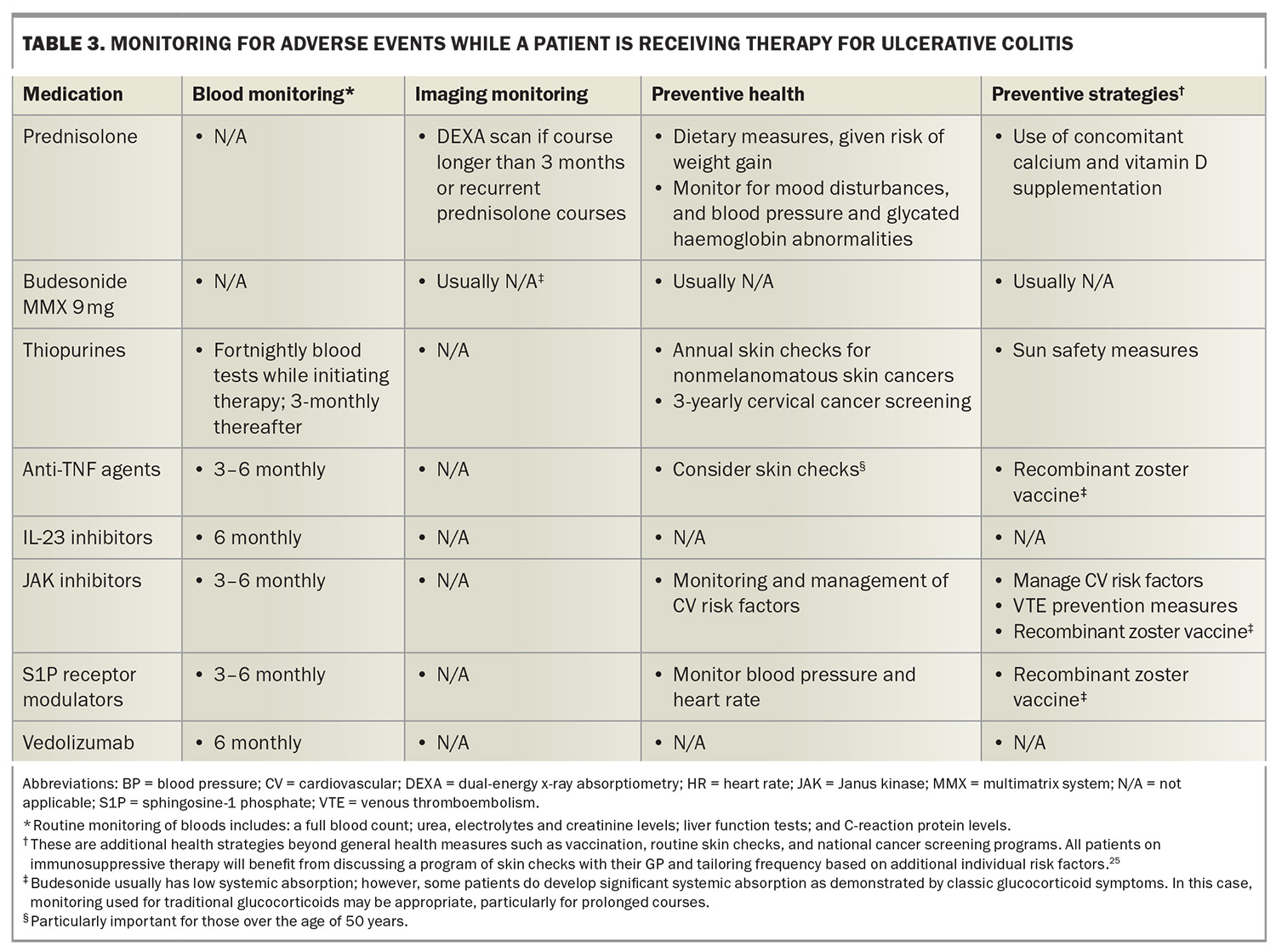

A substantial proportion of patients will either fail to respond to mesalazine (42% in one study)24 and thiopurine therapy, subsequently lose response to therapy, or present with severe disease and require an advanced therapy upfront. Recently, there has been a significant expansion of the number of medications demonstrating efficacy in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, and several of these have obtained PBS approval. An overview of all therapies for ulcerative colitis is presented in Table 2, with monitoring and screening strategies presented in Table 3.17,25

Biologic therapies

Anti-integrin therapies

Anti-integrin therapies block lymphocyte trafficking to the gut, thereby preventing the associated inflammation lymphocytes cause in cases of ulcerative colitis.1 Vedolizumab is a gut-selective anti-integrin (α4β7 integrin blocker) and is the only PBS-listed anti-integrin therapy for ulcerative colitis. Although head-to-head studies are lacking, vedolizumab was shown to have the best long-term persistence (a surrogate marker of effectiveness) of all advanced therapies in a large, multicentre, UK-based ulcerative colitis cohort.26

In addition to its clinical utility, vedolizumab has an excellent safety profile, given it is a gut-selective immunosuppressant.27 A network meta-analysis showed that vedolizumab has the best safety profile compared with other advanced therapies for ulcerative colitis.28 Vedolizumab is usually well tolerated with similar general common side effects experienced with most biologic therapies. Vedolizumab is administered by intravenous induction, followed by either eight-weekly intravenous infusions or fortnightly subcutaneous injections for maintenance therapy.

Vedolizumab is frequently used in patients with ulcerative colitis and often as the first-line advanced therapy, given its efficacy, persistence and excellent safety profile. Vedolizumab often does not work as rapidly as other advanced therapies (anti-TNF and Janus kinase [JAK] inhibitors, in particular) and patients may require corticosteroids or a calcineurin inhibitor as concomitant bridging therapy if they are highly symptomatic or have severe inflammation.29,30 Given that vedolizumab is a gut-selective immunosuppressant, patients with extraintestinal manifestations of disease do not respond well, unless the manifestations are promoted by underlying disease activity, such as some cases of enteropathic arthritis.12 Additionally, vedolizumab is not as effective after previous failure to respond to anti-TNF agents.1

Interleukin-12/23 and interleukin-23 inhibitors

Interleukin (IL)-23 is one of the chief proinflammatory cytokines involved in the pathogenesis and continuing inflammation of ulcerative colitis.31 The first approved and PBS-listed interleukin therapy for ulcerative colitis was ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody to the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23.32 Subsequently, specific IL-23 inhibitors, which target the p19 subunit of IL-23, have demonstrated efficacy in phase 2 and some phase 3 trials.33,34 These include mirikizumab, risankizumab and guselkumab, although these are not yet PBS listed for the treatment of ulcerative colitis or inflammatory bowel disease. Some of these agents are administered by intravenous infusions for induction; however, they are all administered subcutaneously for maintenance therapy.

There are numerous strengths to IL inhibitors. They are often effective in treating numerous extraintestinal manifestations and concomitant autoimmune conditions, such as psoriasis and peripheral small joint arthritis.12 They are usually well tolerated and possess a good safety profile, with studies suggesting no increased risk of infection or malignancy.27 Similar to vedolizumab, they have good persistence rates once they induce remission. In the setting of failing to respond to anti-TNF agents, they may have greater efficacy compared with vedolizumab.1

Antitumour necrosis factor-α agents

TNF-α is another a key proinflammatory cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis and ongoing inflammation of ulcerative colitis.35 Anti-TNF agents are monoclonal antibodies directed against TNF-α. Infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab are the only anti-TNF therapies to have demonstrated efficacy in ulcerative colitis, with the literature suggesting infliximab may be the most effective of the anti-TNF therapies.1,28,36 Golimumab and adalimumab are PBS listed for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, and infliximab for acute severe and moderate to severe ulcerative colitis.

Anti-TNF agents tend to work quickly, enabling relatively quick symptom improvement.37 Anti-TNF agents are very useful in patients with extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease or concomitant autoimmune disorders, as TNF-α plays an important role in these associated conditions.12 Anti-TNF agents are often useful for managing dermatological, arthritic and ophthalmological manifestations. Infliximab is considered one of the most effective medications for patients with severe disease, and is often used as first-line rescue therapy in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis who have failed to respond to intravenous corticosteroids.38

However, there are some limitations with anti-TNF agents. They pose the risk of the immune system developing neutralising antidrug antibodies, which often limits the long-term durability of the drug.39 Concomitant therapy with thiopurines or methotrexate can reduce this risk, but may come with the additional side effects of these medications.22 The potential long-term problems of additional immunomodulator therapy can be reduced when the immunomodulators are used for six to 24 months, mitigating the risk where neutralising antibody formation is the highest.40

Anti-TNF agents exert mild to moderate immunosuppressive effects.27 There is an increased relative risk of lymphoma and skin cancer, particularly when used in combination with a thiopurine. Lastly, anti-TNF agents can have some rare but serious side effects (including demyelination), worsen heart failure and cause drug-induced lupus. Most patients will tolerate anti-TNF agents quite well in clinical practice; however, caution should be applied in treating older patients or those with more comorbidities.

In summary, anti-TNF agents remain a key advanced therapy for ulcerative colitis, particularly in patients with severe disease and those with extraintestinal manifestations. However, the safety profile and possible need for concomitant immunomodulator therapy may lend itself to be a less attractive option in some patients.

Small molecules

Numerous small molecules are now available for the treatment of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. These have numerous benefits including additional modes of action and oral drug administration, reducing the burden on outpatient infusion services.

Janus kinase inhibitors

JAK inhibitors block JAK receptors, limiting signal transduction of the STAT signalling pathway and subsequent activation of numerous proinflammatory cytokines. There are two TGA-approved and PBS-listed JAK inhibitor therapies for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: tofacitinib and upadacitinib.41 Tofacitinib selectively blocks JAK1 and JAK3 receptors, whereas filgotinib and upadacitinib selectively block JAK1.

Tofacitinib and upadacitinib are effective for inducing remission and improving symptoms rapidly.28,42 This has led to the hypothesis that this class may eventually replace corticosteroids for induction therapy. Further, considering their rapid onset of action, their role in the acute severe ulcerative colitis setting is being explored currently.43 In addition, these medications tend to work similarly well whether the patient is naïve to advanced therapies or have failed to respond to other advanced therapies.44-45 This is helpful for clinicians given that subsequent advanced therapies (particularly after failure to respond to anti-TNF agents) have diminishing efficacy in achieving and maintaining disease remission. There are also emerging data on the use of JAK inhibitors in the acute severe ulcerative colitis setting, providing additional key therapies where only ciclosporin and infliximab have previously been recognised as efficacious rescue therapies.38,46 JAK inhibitors are effective in patients with extraintestinal manifestations of disease or concomitant immune-mediated disorders.12 Tofacitinib and upadacitinib have numerous dosing ranges, and they can be up- or down-titrated depending on the clinical response.47,48 However, at higher doses, there is an increased risk of side effects, as other JAK receptors (JAK2, JAK3 and tyrosine kinase-2) may be blocked.49

There are numerous recognised safety concerns associated with JAK inhibitors, including an increased risk of infection, shingles, hypercholesterolaemia, major adverse cardiovascular events, malignancy and venous thromboembolism.22,49 These risks are generally heightened with advanced age and most safety data are based on patients with rheumatoid arthritis.50 This is important to contextualise, given that patients with rheumatoid arthritis have a different underlying pathophysiology, are usually older and have more comorbidities compared with patients with ulcerative colitis. Importantly, the increased risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease has primarily been seen among those with an increased cardiovascular risk or known cardiovascular disease.50 Therefore, safety risks must be contextualised to individual patients.

In summary, JAK inhibitors are a fast-acting and efficacious class of medication, which may limit corticosteroid use and work well for patients with extraintestinal manifestations and those who have failed to respond to previous therapies. However, they do come with important safety concerns.

Sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor modulators

Sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1P) receptor modulators have been used in patients with multiple sclerosis for some time now but have now emerged as an efficacious treatment for ulcerative colitis.51,52 S1P receptor modulators sequester subsets of lymphocytes in peripheral lymph nodes, preventing them from trafficking to areas of inflammation. This is highly useful in ulcerative colitis, given there are high levels of T lymphocytes typically driving inflammation in active disease.

There are two PBS-listed S1P receptor modulators indicated for ulcerative colitis: ozanimod and etrasimod. Ozanimod is a selective S1P1,5 receptor modulator, and etrasimod is a newer-generation S1P1,4,5 receptor modulator.53 The benefits of this class include a different mechanism of action, targeting lymphocytes, rather than cytokines, which is particularly useful in patients with concomitant multiple sclerosis.

Regarding safety, ozanimod and etrasimod are newer and more selective molecules than the original S1P receptor modulators and are therefore associated with fewer side effects than the original generation (e.g. fingolimod used for multiple sclerosis).53 S1P receptor modulators are associated with functional lymphopenia (wherein the lymphocytes are still present in the body but not circulating), which can increase the risk of infection. Trial data have not demonstrated a significantly increased risk of infection in patients with ulcerative colitis, but the occurrence of infection is higher than with some of the other advanced therapies.28,53 Macular degeneration is also a safety consideration; therefore, patients with risk factors for macular disease, in particular patients with diabetes, should be reviewed by their optometrist or ophthalmologist before starting therapy.54

S1P receptor modulators have been associated with cardiac conduction abnormalities. Notably, trial data for ozanimod and etrasimod have not demonstrated an increased risk of cardiac conduction abnormalities, except bradycardia when first introducing ozanimod, but not estrasmiod.53 It is recommended that all patients should undergo an ECG to rule out sinus or AV nodal disease prior to commencing this class of medication. S1P receptor modulators are generally avoided in patients with ischaemic heart disease or cardiac conduction abnormalities.27 Additionally, this class of drugs can cause hypertension and, rarely, malignant hypertension; therefore, patients should have normal or treated blood pressure before starting therapy, with arrangements made for monitoring blood pressure while on the medication.54

In summary, S1P receptor modulators are a novel class of therapy in the ulcerative colitis space, ideal for patients with concomitant multiple sclerosis and convenient to administer. However, they have specific cardiovascular and ophthalmological screening and monitoring requirements.

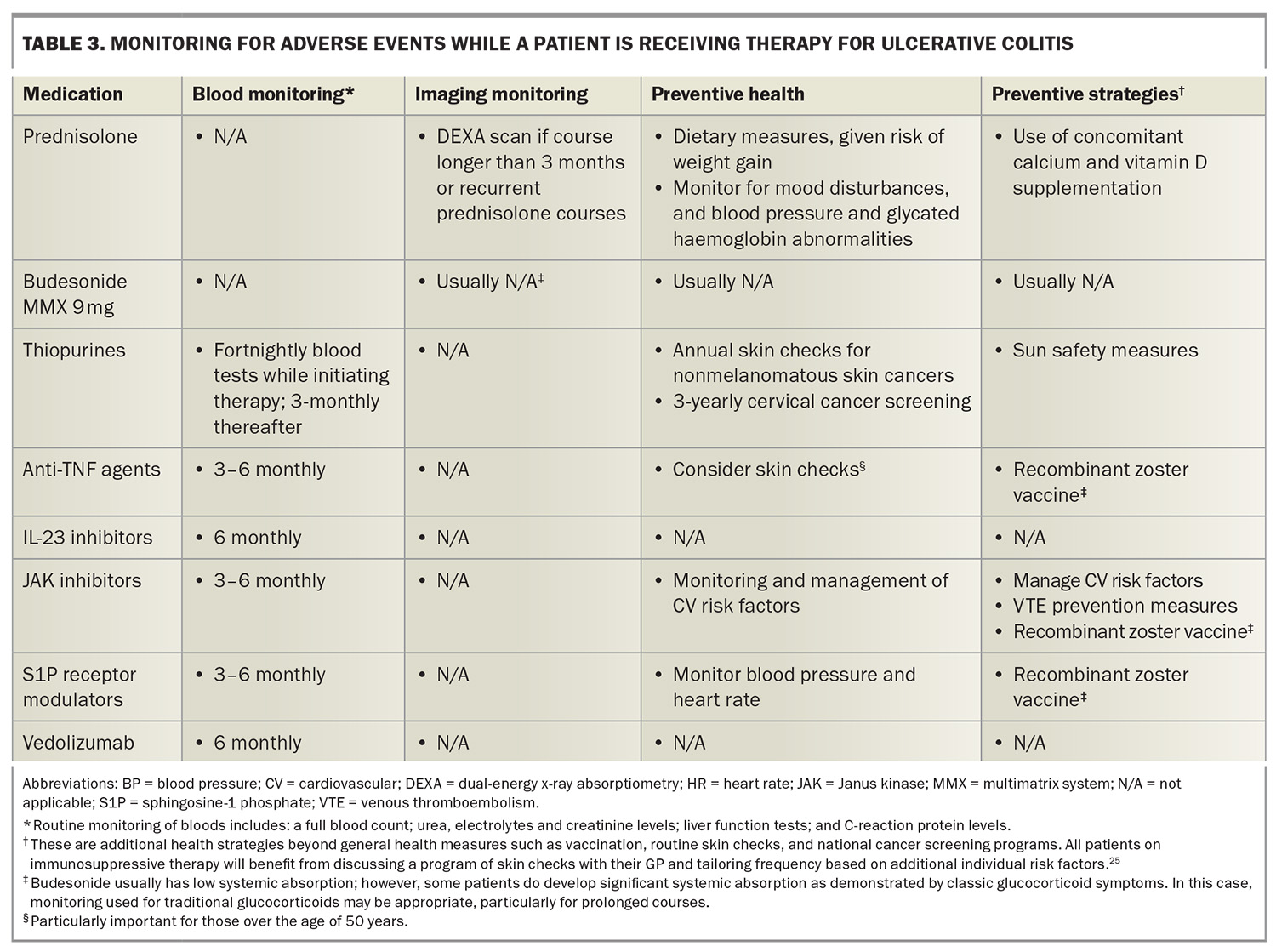

Safety and monitoring of advanced therapies

Adverse events of interest and monitoring requirements are summarised in Table 2 and Table 3.17,25 The PBS require re-application for advanced therapies on a six-monthly basis. This is often an ideal time to perform monitoring, particularly basic blood monitoring. Given the variety of safety and monitoring requirements, ranging from additional vaccinations to monitoring bone health, it is important that all healthcare professionals involved in caring for patients with ulcerative colitis are mindful of preventive health strategies to achieve best outcomes.

Pregnancy

Overall data suggest that biologic therapy is safe in pregnancy and should be continued given the importance of maintaining good disease control throughout pregnancy to optimise outcomes.55 Studies have not demonstrated an increased risk of infection in the first 12 months of life in babies born to mothers on biologic therapy. Live vaccines should not be given in the first six months to babies born to mothers on vedolizumab and IL-23 therapy, and the first 12 months for babies born to mothers on anti-TNF therapy. The only vaccine on the National Immunisation Program schedule this currently affects is the rotavirus vaccine.56

Unlike biologics, small molecules should be avoided in pregnancy and are usually discontinued before conception.55 This recommendation on small molecules is primarily based on animal data, which show increased fetal death and malformation; however, there are limited human data currently. The potential risk of teratogenicity of small molecules must be discussed with women of childbearing age and effective contraception strategies should be put in place. Regarding immunomodulators, thiopurines can be continued throughout pregnancy; however, they should not be started during pregnancy in case a serious complication emerges, such as pancreatitis.55 Methotrexate is teratogenic and should ideally be discontinued three months before conception.21

The modern role of corticosteroids

Glucocorticoids still maintain a role in inducing remission in patients with moderate to severe disease.17 However, prolonged use or recurrent use of corticosteroids is best avoided given the significant side effect profile, with some side effects, such as bone mineral density loss, having a cumulative effect.27 Initiation, optimisation or switching of advanced therapies is often a preferable strategy to manage ulcerative colitis flares.

One strategy to limit the burden of corticosteroids is to use budesonide multimatrix system (MMX) 9 mg, a locally acting glucocorticoid that undergoes extensive hepatic first-pass metabolism, minimising systemic exposure to corticosteroids.17 A limitation of budesonide MMX 9 mg is that the colonic release formulations tend to be more effective in the left colon and, therefore, may not work as well in pan-colonic disease.57 Budesonide is TGA approved for mild to moderate disease, but not moderate to severe disease.17,57 The drug is not PBS listed for the indication of ulcerative colitis; however, numerous tertiary inflammatory bowel disease units will have access to prescribing this drug through their hospital pharmacy. In additional to oral corticosteroids, rectal preparations (e.g. prednisolone suppositories, budesonide enemas) have additional benefits to oral therapies alone and are a useful addition for patients who experience flares.58

The future of medical therapies

There remains a requirement to improve therapeutic strategies for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Remission rates for advanced therapies in clinical trials vary from 30 to 60% for moderate to severe disease, meaning many patients fail to achieve remission with medical therapy alone.59 Promising strategies to improve medical outcomes include novel therapies, dual biologic treatments and faecal microbial transplants.25,60-62 The latter holds significant promise; however, there are several barriers to implementation including setting up appropriate donor banks and systems, along with the intensive and expensive nature of delivering the therapy (endoscopically in numerous trials). However, further studies are in place, investigating the use of oral faecal microbial transplants as an induction and maintenance therapy for inflammatory bowel disease.63

Conclusion

The management of ulcerative colitis encompasses a wide array of medical therapies, each tailored to the severity of the disease. 5-ASA therapy stands out as a viable option for mild cases, offering effective symptom control and disease management. However, for moderate to severe disease, advanced therapies emerge as the preferred choice, offering greater efficacy in achieving disease remission and improving patients’ quality of life. Continued research and clinical evaluation of these therapies are imperative to refine treatment strategies and optimise outcomes for individuals with ulcerative colitis. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Elford has received travel expenses support from Dr. Falk Pharma, Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Galapagos. Associate Professor Christensen has received speaking fees from Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda and Ferring; received research grants from Janssen and Ferring Pharmaceuticals; and served on the advisory boards of Gilead and Novartis.

Acknowledgements: Dr Elford would like to thank the Australian Commonwealth government for their support via a Research Training Program Scholarship.

References

1. Gros B, Kaplan GG. Ulcerative colitis in adults: a review. JAMA 2023; 330: 951-965.

2. Gordon IO, Agrawal N, Willis E, et al. Fibrosis in ulcerative colitis is directly linked to severity and chronicity of mucosal inflammation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 47: 922-939.

3. Busingye D, Pollack A, Chidwick K. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the Australian general practice population: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0252458.

4. Crohn’s & Colitis Australia (CCA). Improving inflammatory bowel disease care across Australia. Camberwell: CCA; 2022. Available online at: https://crohnsandcolitis.org.au/advocacy/our-projects/improving-inflammatory-bowel-disease-care-across-australia/ (accessed January 2025).

5. Du L, Ha C. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2020; 49: 643-654.

6. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel J-F. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2017; 389: 1756-1770.

7. Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al.; International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021; 160: 1570-1583.

8. Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, et al.; IBSEN Study Group. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study). Scand J Gastroenterol 2009; 44: 431-440.

9. Ham M, Moss AC. Mesalamine in the treatment and maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2012; 5: 113-123.

10. Murray A, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 8(8): CD000543.

11. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Sulfasalazine. London: NICE; 2024. Available online at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/sulfasalazine/ (accessed April 2024).

12. Gordon H, Burisch J, Ellul P, et al. ECCO guidelines on extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2024; 18: 1-37.

13. NPS MedicineWise. Oral mesalazine for ulcerative colitis and crohn disease. Sydney: NPS MedicineWise; 2019. Available online at: https://www.nps.org.au/radar/articles/oral-mesalazine-for-ulcerative-colitis-and-crohn-disease (accessed January 2025).

14. Ye B, van Langenberg DR. Mesalazine preparations for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: are all created equal? World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2015; 6: 137-144.

15. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Mesalazine. London: NICE; 2024. Available online at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/mesalazine/ (accessed April 2024).

16. Desreumaux P, Ghosh S. Review article: mode of action and delivery of 5-aminosalicylic acid - new evidence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 24:2-9.

17. Raine T, Bonovas S, Burisch J, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in ulcerative colitis: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis 2022; 16: 2-17.

18. Leifeld L, Pfützer R, Morgenstern J, et al. Mesalazine granules are superior to Eudragit-L-coated mesalazine tablets for induction of remission in distal ulcerative colitis - a pooled analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011; 34: 1115-1122.

19. Stolfi C, Pallone F, Monteleone G. Colorectal cancer chemoprevention by mesalazine and its derivatives. J Biomed Biotechnol 2012; 2012: 980458.

20. Nakashima J, Preuss CV. Mesalamine (USAN). In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. PMID: 31869178.

21. Mantzaris GJ. Thiopurines and methotrexate use in IBD patients in a biologic era. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2017; 15: 84-104.

22. Elford AT, Christensen B. Crohn’s disease: an overview and update on medical and dietary therapies. Medicine Today 2024; 25(1-2): 10-18.

23. Herfarth H, Barnes EL, Valentine JF, et al.; Clinical Research Alliance of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. Methotrexate is not superior to placebo in maintaining steroid-free response or remission in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2018; 155: 1098-1108.e9.

24. Wang Y, Parker CE, Bhanji T, Feagan BG, MacDonald JK. Oral 5-aminosalicylic acid for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 4(4):CD000543. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 8: CD000543.

25. Feagan BG, Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, et al.; VEGA Study Group. Guselkumab plus golimumab combination therapy versus guselkumab or golimumab monotherapy in patients with ulcerative colitis (VEGA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled, phase 2, proof-of-concept trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023; 8: 307-320.

26. Kapizioni C, Desoki R, Lam D, et al.; UK IBD BioResource Investigators; Parkes M, Raine T. Biologic therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: real-world comparative effectiveness and impact of drug sequencing in 13,222 patients within the UK IBD BioResource. J Crohns Colitis 2024; 18: 790-800.

27. Sattler L, Hanauer SB, Malter L. Immunomodulatory agents for treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (review safety of anti-TNF, anti-integrin, anti IL-12/23, JAK inhibition, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator, azathioprine/6-MP and methotrexate). Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2021; 23: 30.

28. Lasa JS, Olivera PA, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Efficacy and safety of biologics and small molecule drugs for patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 7: 161-170.

29. Christensen B, Gibson PR, Micic D, et al. Safety and efficacy of combination treatment with calcineurin inhibitors and vedolizumab in patients with refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17: 486-493.

30. Pellet G, Stefanescu C, Carbonnel F, et al.; Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du tube Digestif. Efficacy and safety of induction therapy with calcineurin inhibitors in combination with vedolizumab in patients with refractory ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17: 494-501.

31. Sewell GW, Kaser A. Interleukin-23 in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease and implications for therapeutic intervention. J Crohns Colitis 2022; 16(2): ii3-ii19.

32. Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Panaccione R, et al.; UNIFI Study Group. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 1201-1214.

33. Verstockt B, Salas A, Sands BE, et al.; Alimentiv Translational Research Consortium (ATRC). IL-12 and IL-23 pathway inhibition in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023; 20: 433-446.

34. D’Haens G, Dubinsky M, Kobayashi T, et al.; LUCENT Study Group. Mirikizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2023; 388: 2444-2455. Erratum in: N Engl J Med 2023; 389: 772.

35. Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14: 329-342.

36. Bonovas S, Lytras T, Nikolopoulos G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Editorial: tofacitinib and biologics for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis-what is best in class? Authors’ reply. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 47: 540-541.

37. Vasudevan A, Gibson PR, van Langenberg DR. Time to clinical response and remission for therapeutics in inflammatory bowel diseases: what should the clinician expect, what should patients be told? World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 6385-6402.

38. Conley TE, Fiske J, Subramanian S. How to manage: acute severe colitis. Frontline Gastroenterol 2021; 13: 64-72.

39. Chaparro M, Guerra I, Muñoz-Linares P, Gisbert JP. Systematic review: antibodies and anti-TNF-α levels in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 35: 971-986.

40. Van Assche G, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, D’Haens G, et al. Withdrawal of immunosuppression in Crohn’s disease treated with scheduled infliximab maintenance: a randomized trial. Gastroenterology 2008; 134: 1861-1868.

41. Herrera-deGuise C, Serra-Ruiz X, Lastiri E, Borruel N. JAK inhibitors: a new dawn for oral therapies in inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023; 10: 1089099.

42. Irani M, Fan C, Glassner K, Abraham BP. Clinical evaluation of upadacitinib in the treatment of adults with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC): patient selection and reported outcomes. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2023; 16: 21-28.

43. Singh A, Midha V, Kaur K, et al. Tofacitinib versus oral prednisolone for induction of remission in moderately active ulcerative colitis [ORCHID]: a prospective, open-label, randomized, pilot study. J Crohns Colitis 2024; 18: 300-307.

44. Honap S, Chee D, Chapman TP, et al.; LEO [London, Exeter, Oxford] IBD Research Consortium. Real-world effectiveness of tofacitinib for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: a multicentre UK experience. J Crohns Colitis 2020; 14: 1385-1393.

45. Chaparro M, Garre A, Mesonero F, et al. Tofacitinib in ulcerative colitis: real-world evidence from the ENEIDA registry. J Crohns Colitis 2021; 15: 35-42.

46. Steenholdt C, Dige Ovesen P, Brynskov J, Benedict Seidelin J. Tofacitinib for acute severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review. J Crohns Colitis 2023; 17: 1354-1363.

47. Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, et al.; OCTAVE Induction 1, OCTAVE Induction 2, and OCTAVE Sustain Investigators. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 1723-1736.

48. Danese S, Vermeire S, Zhou W, et al. Upadacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from three phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, randomised trials. Lancet 2022; 399: 2113-2128. Erratum in: Lancet 2022; 400: 996.

49. Núñez P, Quera R, Yarur AJ. Safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in inflammatory bowel diseases. Drugs 2023; 83: 299-314.

50. Curtis JR, Yamaoka K, Chen YH, et al. Malignancy risk with tofacitinib versus TNF inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the open-label, randomised controlled ORAL Surveillance trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2023; 82: 331-343.

51. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, D’Haens G, et al.; True North Study Group. Ozanimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: 1280-1291.

52. Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Etrasimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (ELEVATE): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies. Lancet 2023; 401: 1159-1171. Erratum in: Lancet 2023; 401: 1000.

53. Verstockt B, Vetrano S, Salas A, Nayeri S, Duijvestein M, Vande Casteele N; Alimentiv Translational Research Consortium (ATRC). Sphingosine 1-phosphate modulation and immune cell trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 19: 351-366. Erratum in: Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 19: 410.

54. Bristol Myers Squib (BMS). Zeposia U.S. Prescribing Information. Mulgrave: BMS; 2024. Available online at: https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_zeposia.pdf (accessed January 2025).

55. Laube R, Selinger CP, Seow CH, et al. Australian inflammatory bowel disease consensus statements for preconception, pregnancy and breast feeding. Gut 2023; 72: 1040-1053.

56. Australian Government. National Immunisation Program Schedule. Canberra: Australian Government, Department of Health and Aged Care; 2024. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/immunisation/when-to-get-vaccinated/national-immunisation-program-schedule (accessed January 2025).

57. Sandborn WJ, Danese S, D’Haens G, et al. Induction of clinical and colonoscopic remission of mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with budesonide MMX 9 mg: pooled analysis of two phase 3 studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41: 409-418.

58. Sandborn WJ, Bosworth B, Zakko S, et al. Budesonide foam induces remission in patients with mild to moderate ulcerative proctitis and ulcerative proctosigmoiditis. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 740-750.e2.

59. Raine T, Danese S. Breaking through the therapeutic ceiling: what will it take? Gastroenterology 2022; 162: 1507-1511.

60. Santiago P, Braga-Neto MB, Loftus EV. Novel therapies for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2022; 18: 453-465.

61. Ahmed W, Galati J, Kumar A, Christos PJ, Longman R, Lukin DJ, Scherl E, Battat R. Dual biologic or small molecule therapy for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 20: e361-e379.

62. Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 1218-1228.

63. Haifer C, Paramsothy S, Kaakoush NO, et al. Lyophilised oral faecal microbiota transplantation for ulcerative colitis (LOTUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 7: 141-151.