Acute rheumatic fever: altering the long-term trajectory

As a result of historical and ongoing challenges, including the impacts of colonisation and disparities in healthcare access, acute rheumatic fever (ARF) in Australia is more commonly diagnosed in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children than in non-Indigenous children. Early recognition and treatment of group A streptococcus pharyngitis and impetigo, which can lead to ARF, can markedly reduce the risk of rheumatic heart disease, especially among this high-risk population.

- Early detection and treatment of group A streptococcus (GAS) pharyngitis and impetigo, particularly in high-risk populations, can prevent the development of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and its sequelae.

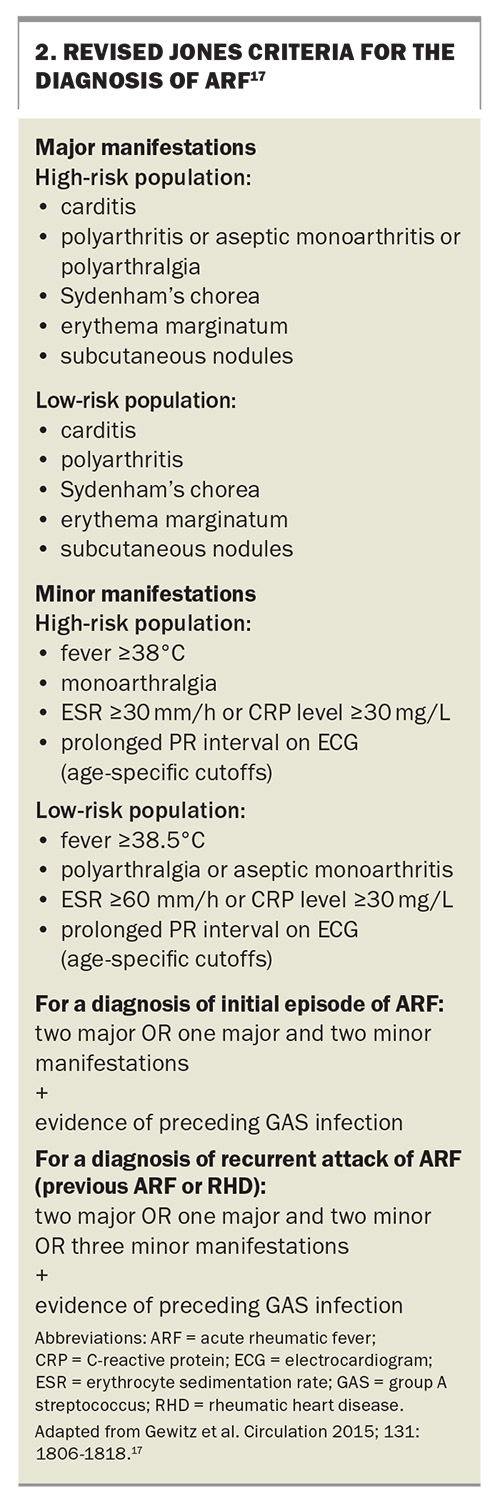

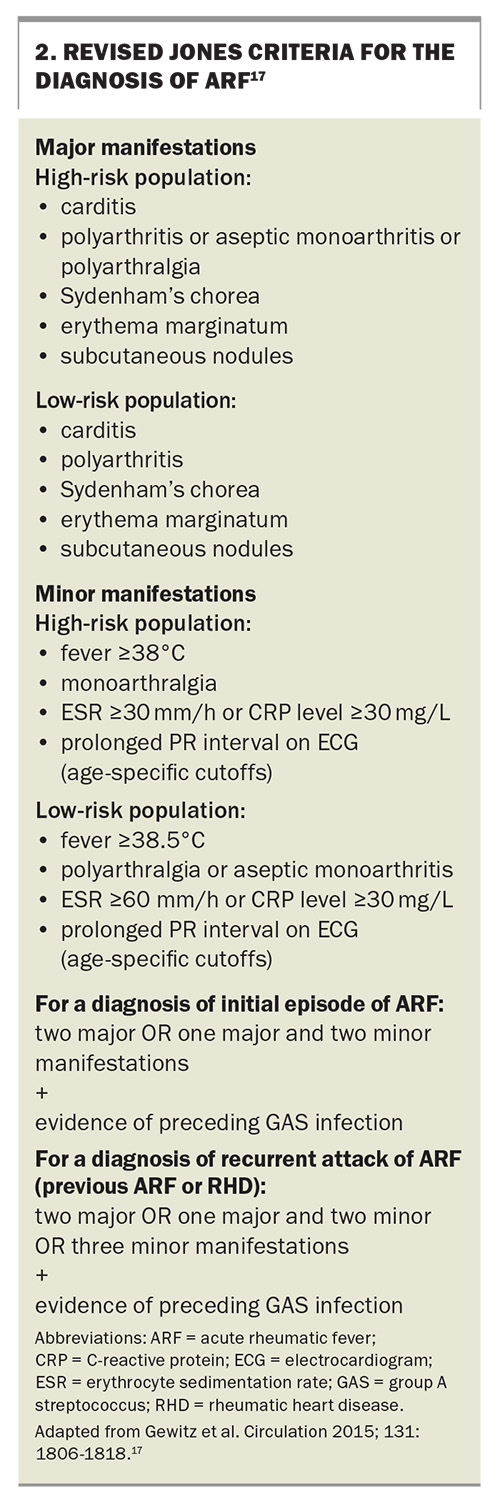

- The revised Jones criteria can be used to diagnose ARF.

- ARF is a notifiable disease in New South Wales, the Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia.

- The clinical features of ARF include arthritis, carditis, Sydenham’s chorea, erythema marginatum and subcutaneous nodules.

- The main secondary prophylactic treatment following ARF development is penicillin, with other treatments specific to organ manifestations.

- GPs play an important role in instituting primary and secondary prevention strategies to reduce morbidity and mortality from ARF and rheumatic heart disease.

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is a preventable post-infectious autoimmune sequela of group A streptococcus (GAS) infection. Its incidence and severity are tightly linked to the timely recognition and treatment of preceding GAS infections. In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in remote and rural areas experience a disproportionately high burden of GAS infections.1 Current evidence shows that appropriate antibiotic treatment of GAS pharyngitis can significantly reduce immunological sequelae by up to 70%.2 Although the role of treating GAS skin sores in preventing immunological sequelae has not been proven, it is theoretically plausible that such treatment could have similar benefits to those seen when treating GAS pharyngitis.3-5 The role of primary care practitioners in altering the course of this disease is invaluable.

Epidemiology

ARF primarily affects young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 5 to 14 years, with a corresponding peak incidence of rheumatic heart disease (RHD) in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 35 to 44 years.6 In 2023, there were only 600 diagnoses of ARF recorded.6 Although the incidence of ARF is not high on a population basis, 91% of these diagnoses were in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and the incidence in this high-risk population has increased over the past eight years.6 The Northern Territory had the highest rate of ARF diagnoses per 100,000 population, followed by Western Australia, Queensland, South Australia and New South Wales. ARF has been a notifiable disease in Victoria since 2023 and is not a notifiable disease in Tasmania.8 The majority of cases (85.7%) of ARF were diagnosed in remote regions, but 6.1% occurred in regional areas and 6.7% in major cities, underscoring that ARF can still occur in urban settings.6

The exact cause of the rising incidence of ARF remains unclear, but it may be attributed to undertreated GAS infections and increased notification reporting.6 These statistics highlight unmet needs in screening and access to disease-altering antibiotics.

Pathogenesis

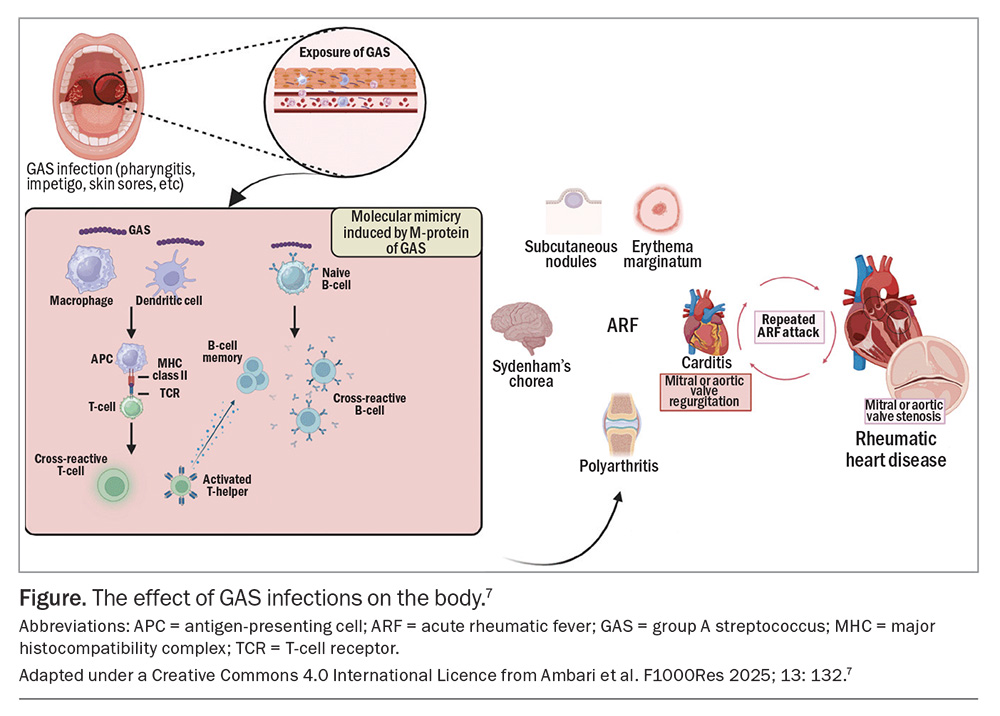

GAS, or Streptococcus pyogenes, is a Gram-positive, human-specific pathogenic bacterium responsible for a spectrum of infections including impetigo, septicaemia and necrotising fasciitis. Most notably, it can cause pharyngitis that can develop into ARF and subsequent RHD in 3 to 6% of cases.9 ARF is an aberrant immune response to a GAS infection, usually occurring two to four weeks after the initial infection.10

Molecular mimicry is implicated as a crucial pathogenic step, as the M-protein on the GAS resembles human cardiac tissue, causing immune cells to cross-react and attack the cardiac myosin in susceptible hosts (Figure).7,11 This process exposes normally intracellular cardiac proteins, triggering the development of additional autoantibodies against these proteins. The resultant carditis and valvulitis ultimately lead to congestive cardiac failure.12

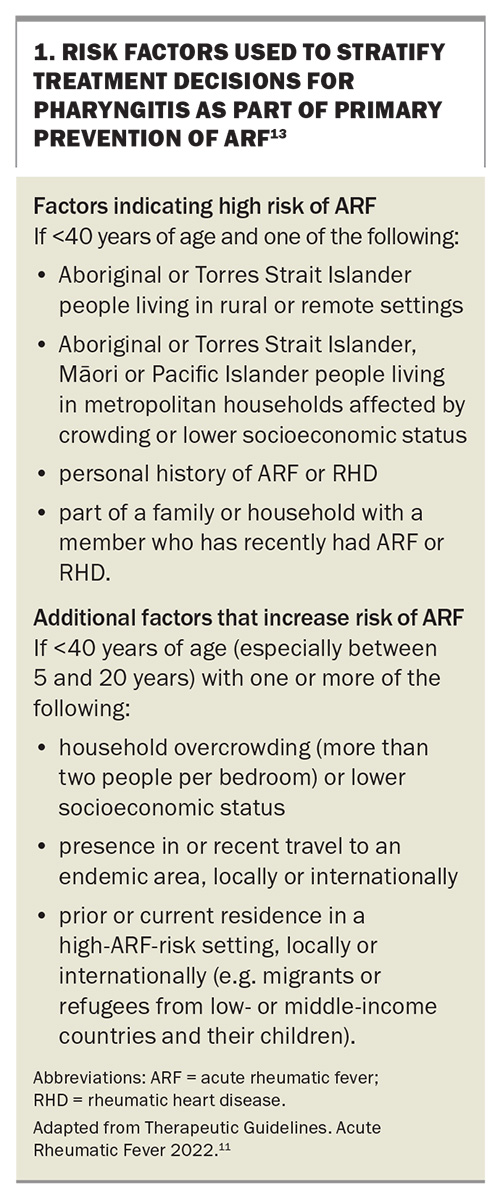

The progression from GAS infections to ARF is influenced by both disease-associated risk factors, such as the organism’s virulence and the frequency of GAS infections, and individual risk factors, including social determinants of health. Risk factors for the progression of pharyngitis to ARF are listed in Box 1.13 These risk factors are used to stratify treatment decisions for pharyngitis as part of the primary prevention of ARF.

Primary prevention

GAS infection remains a significant global concern. While the World Health Organization and local organisations endeavour to develop an appropriate vaccine, early prevention remains the mainstay of management.14 Primordial prevention by addressing underlying factors is essential at the population level; these factors include overcrowding, language differences, inadequate housing, and limited access to or trust in health services. However, primary prevention offers a significant opportunity for GPs to intervene early. This involves the accurate recognition, risk stratification and treatment of individuals with superficial GAS infections, impetigo and pharyngitis. Initiating antibiotics within nine days of the onset of GAS pharyngitis can reduce the incidence of ARF by about 70 to 80%.2,15

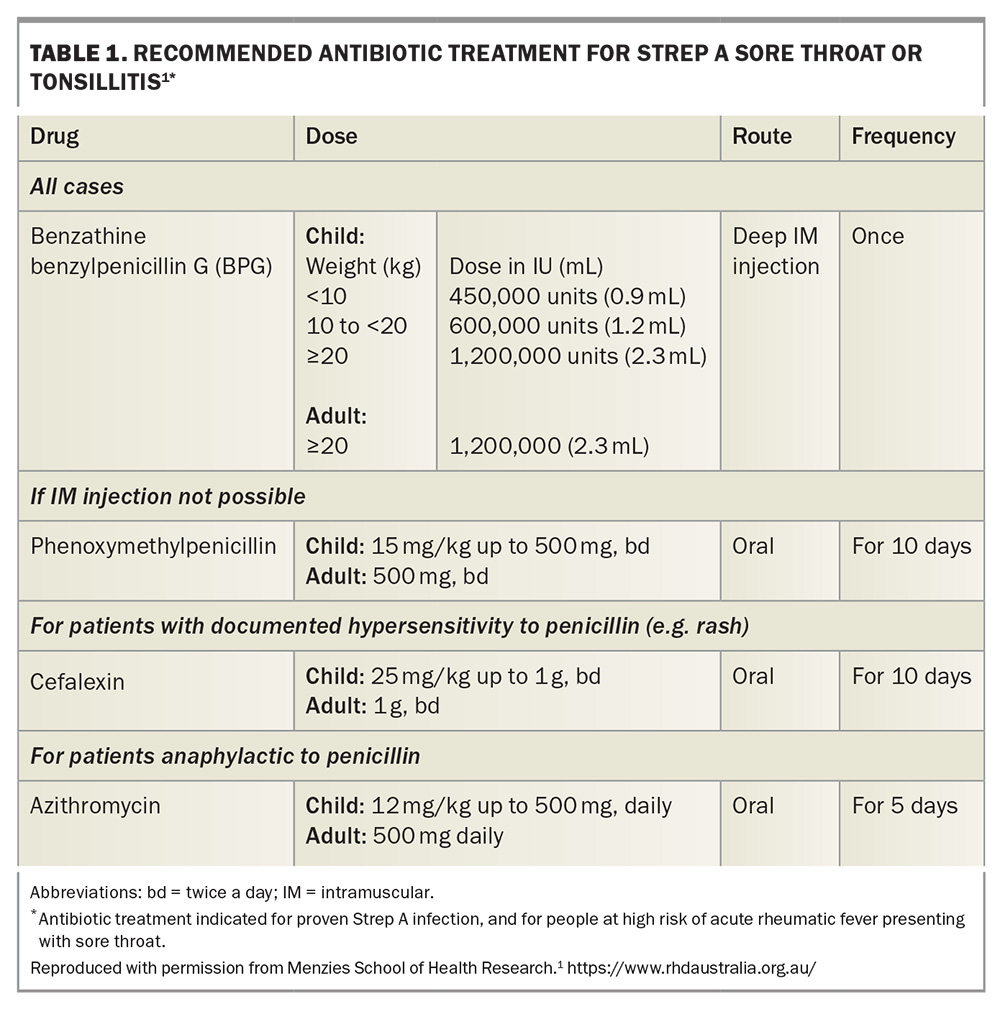

Acute pharyngitis is a common presentation to GPs and although most sore throats are caused by viruses, around 20 to 40% of these infections will be caused by GAS.1 It is clinically difficult to differentiate between pharyngitis caused by viruses and that caused by GAS. Therefore, in people who are at high risk of ARF (Box 1),13 empirical treatment should be initiated while concurrently investigating for GAS infection with a throat swab. In those who are not at high risk, a swab should be performed first and if positive, then the patient should be treated with antibiotics (Table 1).1 Antibiotic treatment for skin sores may also reduce the overall burden of GAS-related diseases, including ARF.1,16 The infectious period for GAS infections is usually from 10 to 21 days, but penicillin treatment may reduce this period to within 24 hours, further highlighting the importance of early recognition and treatment.6

Acute rheumatic fever diagnosis

The current diagnosis of initial and recurrent ‘definite ARF’ is made using the revised Jones criteria (Box 2).17 Evidence of preceding GAS pharyngitis is confirmed through either a positive throat swab, rapid antigen or nucleic acid test, or elevated anti-streptolysin O or anti-DNase B titres, and the pharyngitis usually predates symptoms by two to three weeks.6,18 It is essential to consider age-specific cutoffs for antibody titres (because children develop increasing titres until 9 to 12 years of age and then antibody titres decline with age) and that a comparison to a baseline titre may be required.1,17,19 It should also be noted that antistreptococcal antibody titres rise at one week after initial infection, the anti-streptolysin O titre peaks at three weeks and anti-DNase B titres peak at six to eight weeks but may persist at high levels for years, particularly in the context of recurrent superficial GAS infections.1

‘Probable ARF’ denotes a clinical presentation where ARF is considered the most likely diagnosis but there is an absence of one major or one minor manifestation or the lack of positive streptococcal serology. ‘Possible ARF’ refers to cases where the diagnosis of ARF is less likely than other possibilities but cannot be ruled out entirely.17

ARF is a notifiable disease in New South Wales, the Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Victoria but not in Tasmania or the Australian Capital Territory. RHD is notifiable to the Public Health Unit by clinicians in New South Wales, South Australia, Western Australia and Victoria.8

Major clinical features of ARF include arthritis, carditis, chorea, erythema marginatum and subcutaneous nodules.10,17 Although many patients report a prior sore throat, some preceding cases of GAS pharyngitis are subclinical and can only be confirmed using streptococcal antibody testing. Most cases of ARF occur in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, but there are subtle presentations of ARF that have been missed in other children.20

Arthritis

In Australia, arthritis is the most common presentation in patients with ARF, typically presenting as an abrupt migratory polyarthritis affecting the large joints in an asymmetrical manner, including the elbows, hips, knees and ankles.1,6,21 This condition is characterised by exquisite tenderness, with pain that is out of proportion to clinical signs. It is necessary to distinguish between arthritis, which is evident by a hot, swollen joint with pain upon movement, and arthralgias, which refer to joint pain without clinically evident swelling or heat.

In populations at higher risk of ARF, the presence of less severe joint involvement with arthralgias or aseptic monoarthritis fulfils a major criterion for ARF diagnosis. This contrasts with the requirement of polyarthritis for ARF diagnosis in low-risk populations. It is important to note that joint manifestations can serve as either the major or minor criterion but not both in the same patient (Box 2).1,6,17

Carditis

Carditis is the second most common presentation of ARF, and given the significance of carditis in ARF, guidelines recommend evaluating the heart in each presentation.1 Any part of the heart may be affected, but the predominant presentation occurs with valvular damage of the mitral or aortic valves. This can manifest as heart murmurs or with features of heart failure, displaced apex beat (cardiac enlargement and dysfunction) or a pericardial friction rub (pericardial involvement). Subclinical carditis is best determined by echocardiography, which is essential in diagnosing valvular damage, defining regurgitation severity, assessing cardiac function and determining pericardial involvement.22 Inflammation of the myocardium leads to PR interval prolongation, which is a minor diagnostic criterion. In the same patient, if carditis is used as a major criterion, then the PR interval cannot be used as a minor criterion.1

Over half of all patients with ARF progress to RHD within 10 years.23 Predictors of RHD include the virulence of the organism, the number of episodes of ARF and genetic predisposition. In about one-quarter of Australians who are diagnosed with RHD, it leads to cardiovascular complications or death after eight years.24 An epidemiological study from 2021 showed that 85% of all new RHD cases were in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and 11% of new diagnoses were among the migrant population.24

Sydenham’s chorea

Sydenham’s chorea stands out as a pivotal clinical sign because its presence alone is adequate for diagnosing ARF, even in the absence of preceding GAS infection, provided alternative causes are ruled out.1,17 Chorea can manifest late in the clinical course, usually six to nine weeks following preceding GAS infection and after the resolution of other symptoms.17,18 Consequently, confirmatory evidence of GAS infection can be challenging to obtain when the patient presents with chorea. Clinically, patients present with jerky and unco-ordinated involuntary movements of the hands, feet and facial muscles that are absent in sleep, in contrast to seizure-like activity, and can be momentarily suppressed under conscious control.6 Chorea is the symptom most prone to recurrence.1

Erythema marginatum

Erythema marginatum, an uncommon but also highly specific symptom of ARF, manifests as an early evanescent, non-pruritic, pink macular rash with central clearing and a serpiginous spreading edge. It originates on the trunk and spares the face.1 This can be difficult to detect in dark-skinned people but may be brought out by heat and may leave a mild reduction in pigmentation.25

Subcutaneous nodules

Subcutaneous nodules, although a rare manifestation, are highly specific for ARF in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Typically painless, these nodules present as round, firm and freely mobile nodules in symmetrical crops over the hands, elbows, knees, ankles, wrists and occiput within the first two weeks of illness.1

Minor manifestations

The most common minor manifestation is fever, which is present in up to 90% of patients with ARF.15 Other minor manifestations include elevated acute phase reactants, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein levels. Notably, there are subtle differences between high- and low-risk populations regarding cutoffs for fever (38°C for high risk and 38.5°C for low risk) and peak ESR elevation (30 mm/h for high risk and 60 mm/h for low risk) (Box 2).17

Secondary prophylaxis

The administration of antibiotics to individuals who have been diagnosed with ARF plays a critical role in preventing ARF recurrence and the development of RHD. Patients with suspected ARF should be hospitalised to facilitate access to diagnostic testing, echocardiography and early specialist involvement.13 This is particularly pertinent in the paediatric age group.

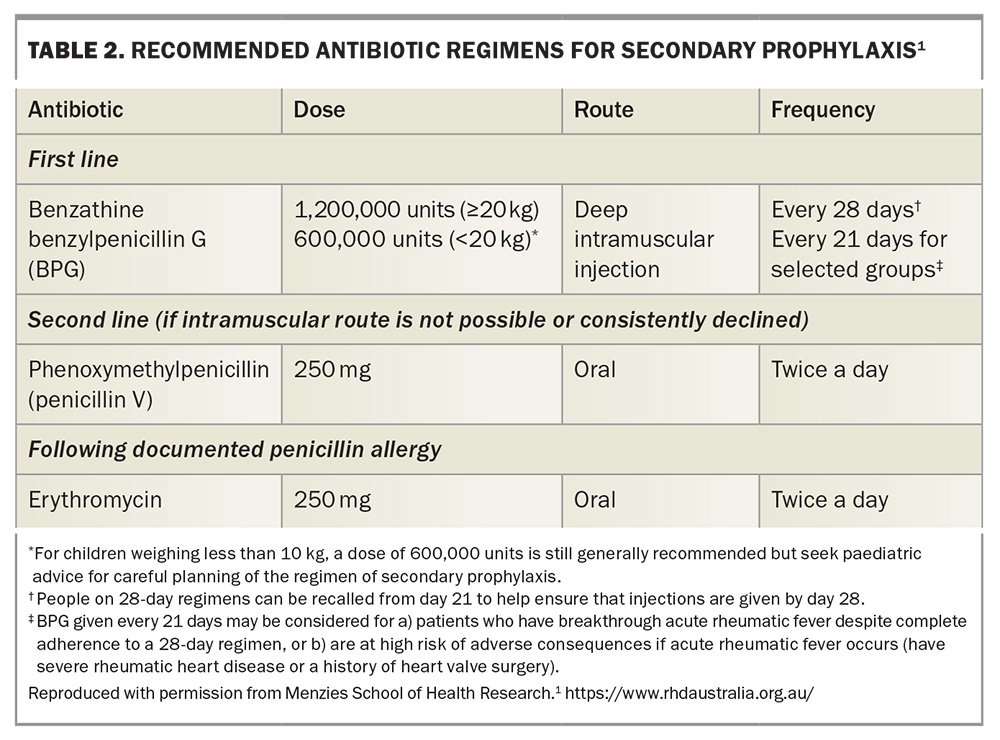

Penicillin-based antibiotics are the treatment of choice, with intramuscular benzathine benzylpenicillin G injections as first-line treatment for their improved adherence and a more consistent penicillin concentration, followed by oral phenoxymethylpenicillin as second-line treatment.1,26 For individuals in whom penicillin hypersensitivity is dubious, consider referring the patient to an allergy clinic for evaluation and possible penicillin challenge. Erythromycin is an alternative for those with penicillin hypersensitivity (Table 2).1

Individuals with ‘probable ARF’ should receive the same secondary prophylaxis as those with ‘definite ARF’ without cardiac involvement – benzathine benzylpenicillin G for five years or until age 21 years, whichever is longer. Those with ‘possible ARF’ only require one year of secondary prophylaxis but do require further review, including echocardiography, to determine whether ARF was in fact present. For those with RHD and a history of ARF, the duration of secondary prophylaxis depends on the severity of the rheumatic valve disease and whether there is a documented history of rheumatic fever: it ranges from prophylaxis until 21 years of age for mild RHD to up to 40 years of age for severe RHD.1,13

Symptom management in ARF

Symptomatic treatment of arthralgias is primarily with NSAIDs such as naproxen, initiated after the diagnosis of ARF has been confirmed.27 Before diagnosis, paracetamol may be used until the diagnostic criteria are met. The polyarthritis associated with ARF is remarkably responsive to anti-inflammatories, such as NSAIDs or salicylates, with noticeable improvement observed within three days of initiating treatment.1 Thus, alternative diagnoses should be considered in those who do not respond to NSAID therapy. Rebound arthritis can occur once NSAIDs are ceased but typically responds to a second course of anti-inflammatory treatment.1 Failure to respond should prompt referral of the patient to a specialist to consider alternative diagnoses and for further management.

For the acute management of carditis and heart failure, appropriate diuresis is crucial after assessment with an electrocardiogram, chest x-ray and echocardiogram. Specialist involvement and consideration for hospitalisation is recommended in refractory cases.

The management of Sydenham’s chorea depends on severity. For those with moderate-to-severe chorea, including difficulty with gait and self-care activities, anticonvulsants such as sodium valproate and carbamazepine are first-line treatments.1,28,29

Conclusion

Despite its low incidence, ARF remains a critical diagnosis that should not be overlooked, because GPs can play a pivotal role in improving patient outcomes. Maintaining a high level of suspicion in at-risk groups, such as those living in GAS-endemic areas, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people residing in remote or crowded settings, and those presenting with characteristic symptoms (including arthritis, carditis, Sydenham’s chorea, erythema marginatum and subcutaneous nodules) will enhance detection and treatment. The implementation of both primary and secondary prophylaxis, along with early referral to the hospital for appropriate workup, can significantly alter the long-term trajectory for patients, helping to prevent ARF recurrence and the complications of RHD. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. RHDAustralia (ARF/RHD writing group). The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3.2 edition, March 2022). Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research; 2020. Available online at: https://www.rhdaustralia.org.au/arf-rhd-guideline (accessed February 2025).

2. Robertson KA, Volmink JA, Mayosi BM. Antibiotics for the primary prevention of acute rheumatic fever: a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2005; 5: 11.

3. Pickering J, Sampson C, Mullane M, et al. A pilot study to develop assessment tools for Group A Streptococcus surveillance studies. PeerJ 2023; 11: e14945.

4. McDonald M, Currie BJ, Carapetis JR. Acute rheumatic fever: a chink in the chain that links the heart to the throat? Lancet Infect Dis 2004; 4: 240-245.

5. Williamson DA, Smeesters PR, Steer AC, et al. M-protein analysis of Streptococcus pyogenes isolates associated with acute rheumatic fever in New Zealand. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53: 3618-3620.

6. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia 2023. Catalogue number CVD 100. Canberra: AIHW, Australian Government; 2024. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/0463f5cc-1db7-4c5d-9896-a933a7a0130c/aihw-cvd-100-acute-rhumatic-fever-and-rheumatic-heart-disease-in-australia-2022.pdf (accessed March 2025).

7. Ambari AM, Qhabibi FR, Desandri DR, et al. Unveiling the group A streptococcus vaccine-based L-rhamnose from backbone of group A carbohydrate: current insight against acute rheumatic fever to reduce the global burden of rheumatic heart disease. F1000Res 2025; 13: 132.

8. Department of Health, Victoria. Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD). Available online at: https://www.health.vic.gov.au/infectious-diseases/acute-rheumatic-fever-arf-and-rheumatic-heart-disease-rhd#notification-requirement-for-arf-and-rhd (accessed March 2025).

9. Carapetis JR, Currie BJ, Mathews JD. Cumulative incidence of rheumatic fever in an endemic region: a guide to the susceptibility of the population? Epidemiol Infect 2000; 124: 239-244.

10. Sika-Paotonu D, Beaton A, Raghu A, Steer A, Carapetis J. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Oklahoma City: University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; 2017. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425394/ (accessed February 2025).

11. Brouwer S, Rivera-Hernandez T, Curren BF, et al. Pathogenesis, epidemiology and control of Group A Streptococcus infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023; 21: 431-447.

12. Carapetis JR, Beaton A, Cunningham MW, et al. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2: 15084.

13. Therapeutic Guidelines. Acute rheumatic fever 2022. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines; 2022. Available online at: https://tgldcdp.tg.org.au.acs.hcn.com.au/viewTopic?etgAccess=true&guidelinePage=Antibiotic&topicfile=rheumatic-fever&guidelinename=Antibiotic§ionId=toc_d1e47#toc_d1e47 (accessed February 2025).

14. Walkinshaw DR, Wright MEE, Mullin AE, Excler J-L, Kim JH, Steer AC. The Streptococcus pyogenes vaccine landscape. NPJ Vaccines 2023; 8: 16.

15. Catanzaro FJ, Stetson CA, Morris AJ, et al. The role of the streptococcus in the pathogenesis of rheumatic fever. Am J Med 1954; 17: 749-756.

16. Bowen AC, Mahé A, Hay RJ, et al. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0136789.

17. Gewitz MH, Baltimore RS, Tani LY, et al. Revision of the Jones Criteria for the diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever in the era of Doppler echocardiography: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 131: 1806-1818.

18. Steer A, Gibofsky A. Acute rheumatic fever: clinical manifestations and diagnosis. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2024. Available online at: Available online at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-rheumatic-fever-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis/ (accessed March 2025).

19. Renneberg J, Söderström M, Prellner K, Forsgren A, Christensen P. Age-related variations in anti-streptococcal antibody levels. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1989; 8: 792-795.

20. Noonan S, Zurynski YA, Currie BJ, et al. A national prospective surveillance study of acute rheumatic fever in Australian children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013; 32: e26-e32.

21. Communicable Diseases Network Australia (CDNA). Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD): CDNA National Guidelines for Public Health Units. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, Department of Health and Aged Care; 2018. Available online at: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/acute-rheumatic-fever-and-rheumatic-heart-disease-cdna-national-guidelines-for-public-health-units?language=en (accessed March 2025).

22. Rwebembera J, Marangou J, Mwita JC, et al. 2023 World Heart Federation guidelines for the echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2024; 2: 250-263.

23. Lawrence JG, Carapetis JR, Griffiths K, Edwards K, Condon JR. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: incidence and progression in the Northern Territory of Australia, 1997 to 2010. Circulation 2013; 128: 492-501.

24. Stacey I, Hung J, Cannon J, et al. Long-term outcomes following rheumatic heart disease diagnosis in Australia. Eur Heart J Open 2021; 1: oeab035.

25. West M. Erythema marginatum rheumatic fever: Symptoms and more. MedicalNewsToday. 2024. Available online at: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/erythema-marginatum-rheumatic-fever (accessed February 2025).

26. Manyemba J, Mayosi BM. Penicillin for secondary prevention of rheumatic fever. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002; 2002: CD002227.

27. Hashkes PJ, Tauber T, Somekh E, et al. Naproxen as an alternative to aspirin for the treatment of arthritis of rheumatic fever: a randomized trial. J Pediatr 2003; 143: 399-401.

28. Genel F, Arslanoglu S, Uran N, Saylan B. Sydenham’s chorea: clinical findings and comparison of the efficacies of sodium valproate and carbamazepine regimens. Brain Dev 2002; 24: 73-76.

29. Dean SL, Singer HS. Treatment of Sydenham’s chorea: a review of the current evidence. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) 2017; 7: 456.