Inflammatory arthritis and ocular complications: an overview

Inflammatory arthritis often leads to debilitating symptoms and systemic manifestations. Among its various complications, ocular involvement remains a concern, affecting up to 40% of patients with inflammatory arthritis.

- Inflammatory arthritis can cause debilitating symptoms and systemic manifestations. Some types include rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, enteropathic arthritis and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis.

- Ocular complications in people with inflammatory arthritis can affect almost any structure of the eye, with acute anterior uveitis being the most frequent ocular complication, especially in those with ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis.

- The diagnosis of ocular complications relies on clinical assessment, ophthalmic examination and laboratory investigations. Early recognition and appropriate referral to an ophthalmologist are crucial for managing ocular involvement in patients with inflammatory arthritis.

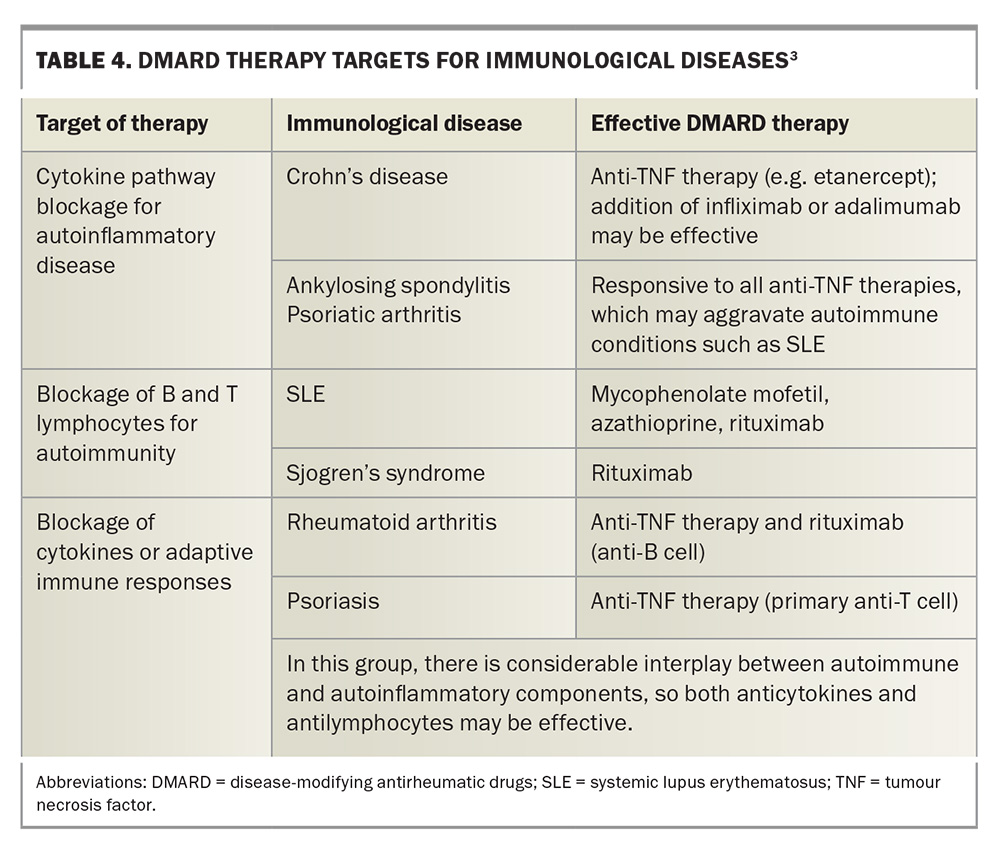

- There are various treatment options for ocular complications, including corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologics targeting specific cytokines. The response to treatment varies depending on the type of ocular manifestation and the underlying inflammatory arthritis.

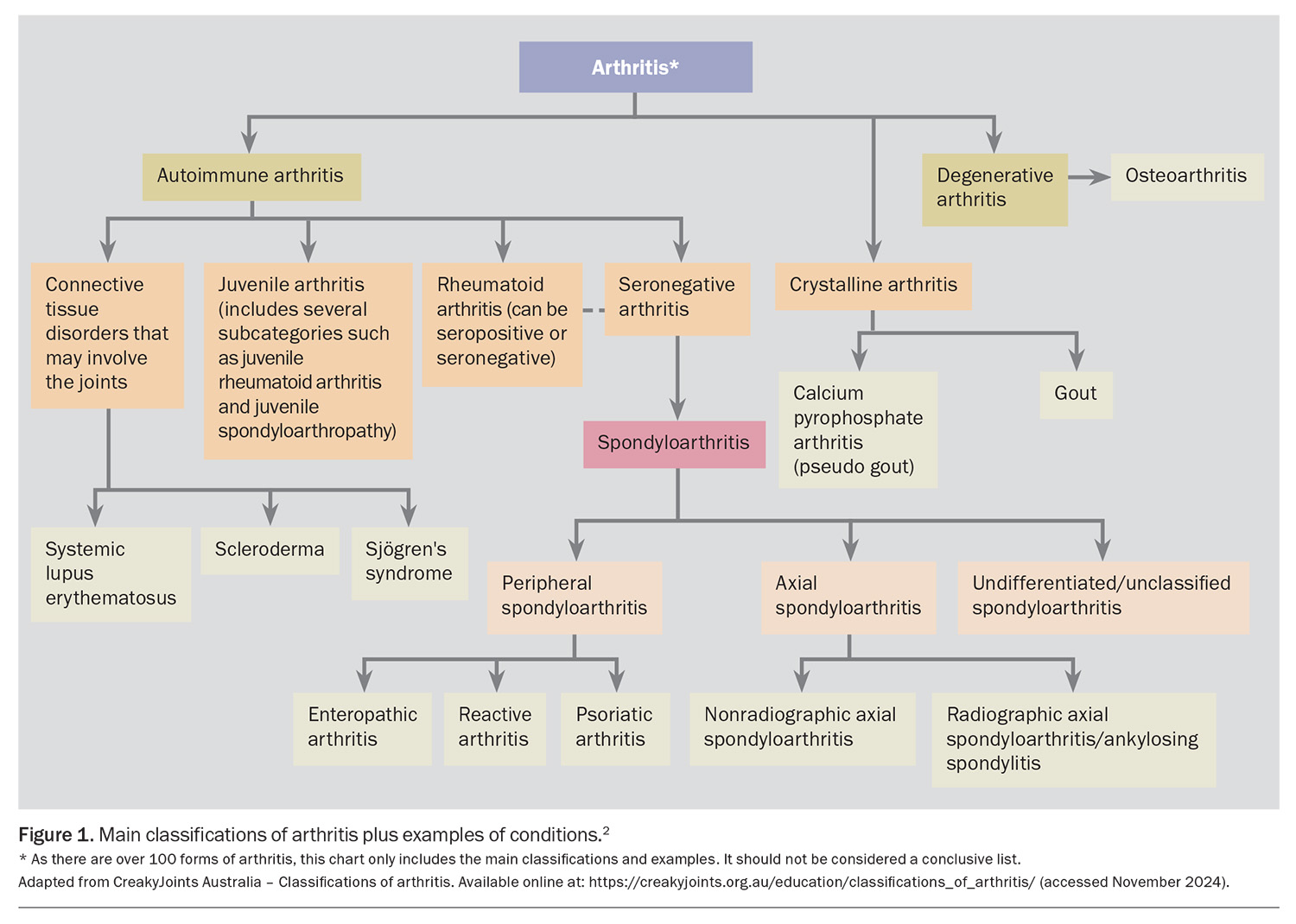

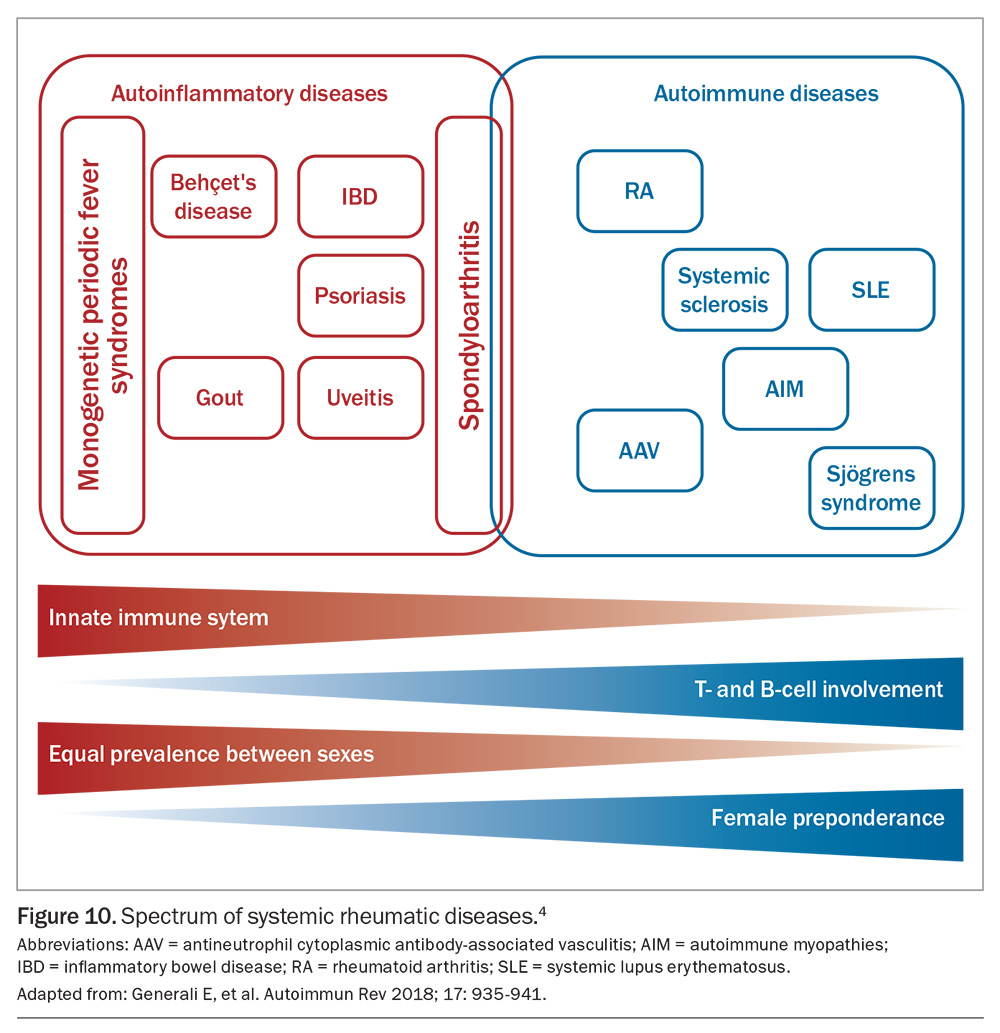

Inflammatory arthritis encompasses a spectrum of autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders characterised by chronic or recurrent inflammation of the joints and extra-articular tissues.1 Common classifications of arthritis and examples of conditions are outlined in Figure 1.2

Autoinflammatory diseases are determined by a dysregulation of innate immunity without the development of specific markers of an autoimmune response, such as autoreactive T cells and autoantibodies.1,3 Many of the recognised autoinflammatory diseases are caused by point mutations in genes that control the innate immune response.1

Inflammatory arthritis may also be classified as seronegative or seropositive. Seropositivity is characterised by a positive result for antibodies in blood serum. The seronegative arthropathies include spondyloarthropathies (SpAs), which are ‘mixed-pattern diseases’, having features consistent with both autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders.4 They may be further classified as nonaxial (psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, enteropathic arthritis) or axial (ankylosing spondylitis). Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the definitive seropositive disorder (rheumatoid factor-positive), but the condition can also be seronegative. Connective tissue disorders that may involve the joints include scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjögren’s syndrome. Additionally, some systemic vasculitides may develop into an inflammatory arthropathy, such as Behçet’s disease and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV).

This article provides GPs with a comprehensive overview of inflammatory arthritis, with an emphasis on ocular complications and management strategies to facilitate early recognition and appropriate referral for specialised care of ocular involvement in patients with inflammatory arthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis

RA is a systemic inflammatory disease that primarily affects the peripheral joints in a symmetrical pattern.5 Extra-articular organ manifestations are present in 10 to 20% of patients, and are most frequent in those who test seropositive.5,6 These include pericarditis, pleuritis, major cutaneous vasculitis, neuropathy, ocular manifestations, glomerulonephritis and other types of vasculitis.5 The prevalence of ocular involvement in RA was found to be 18% in a meta-analysis.6 Women are three times more likely to be affected than men, with 80% of patients developing the disease between 35 and 50 years of age.7

The aetiology of RA is unknown and its pathogenesis remains unclear, but both genetic factors and autoimmune elements are involved.5,7 Proinflammatory cytokines secreted by macrophages (e.g. tumour necrosis factor [TNF]-α, interleukin [IL]-1 and IL-6) play a critically important role in the induction and propagation of chronic inflammation.7 CD4-positive T cells play a major role in joint inflammation and B cells produce autoantibodies known as rheumatoid factors (RFs).5 Patients with higher titres of RFs are more likely to have extra-articular manifestations of their disease, including ocular complications.7

ANCA-associated vasculitis

AAV encompasses a group of multisystem, life-threatening and relapsing small- to medium-vessel vasculitic diseases, which include eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA; previously known as Churg-Strauss syndrome), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA; previously known as Wegener’s granulomatosis) and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).8 These diseases have marked heterogeneity in presentation and can affect any part of the body, but mainly involve the lungs, kidneys, skin, nervous system and sinonasal tract.9 Autoimmune reactions can be triggered by multiple mechanisms, leading to granulomatous inflammation in the blood vessel walls and fibrinoid necrosis.10 Among a typical GP clinic that sees 8000 patients, roughly one new case can be expected every five years.8

ANCA, which characterises AAV, consists of two subtypes:

- perinuclear ANCA, directed against myeloperoxidase (MPO) antigens

- cytoplasmic ANCA, directed against proteinase 3 (PR3) antigens.11

PR3-ANCA (cytoplasmic) is detected in most patients with GPA, whereas MPO-ANCA (perinuclear) is detected in most patients with MPA and about 50% of patients with EGPA.11 ANCA specificity is predictive of long-term prognosis; patients who test positive for PR3-ANCA are at a higher risk of relapse than those who test positive for MPO-ANCA.11 The results of ANCA testing can be negative in about 10% of patients with AAV.12

Spondyloarthropathies

SpAs include psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, enteropathic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis; the latter is frequently associated with extra-articular manifestations, such as uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease.4 In contrast to other rheumatic diseases, SpAs affect both sexes equally.

SpAs are poorly responsive to corticosteroid treatment, but disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are often effective therapy for milder disease.4 SpAs respond to biologics that target TNF-α, IL-6, IL-23 and IL-17, especially bimekizumab. Extra-articular manifestations, such as uveitis, have different drug response profiles, with uveitis being very responsive to corticosteroids and TNF-α and IL-6 blockade, but poorly responsive to biologics that target IL-23 and IL-17.

The spectrum of SpAs is variably associated with the class 1 human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 allele, without detectable serum autoantibodies (hence being seronegative). SpAs may be better classified as autoinflammatory diseases.4 Ankylosing spondylitis has the highest association with up to 90% of patients having HLA-B27 positivity.4 Intriguingly, isolated acute anterior uveitis (AAU) is also strongly associated with HLA-B27.4 Forty percent of patients presenting with AAU have underlying undiagnosed SpA and, therefore, AAU should be considered an important red flag for both GPs and ophthalmologists to pursue further screening.13

Ocular complications

The diagnosis of ocular complications relies on a combination of clinical assessment, ophthalmic examination and laboratory investigations. Any patient presenting with ocular symptoms, such as eye pain, redness, photophobia or blurred vision, in the context of a diagnosis (or presumptive diagnosis) of inflammatory arthritis should undergo a thorough eye examination by an ophthalmologist.

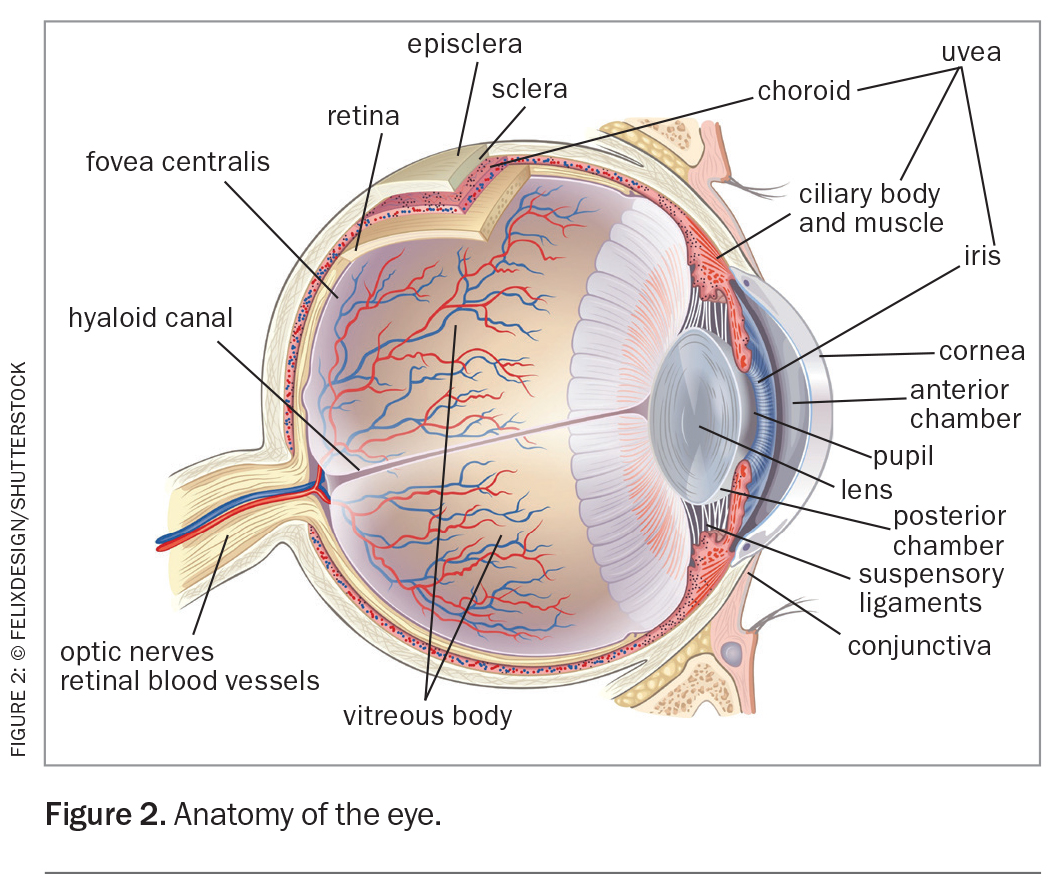

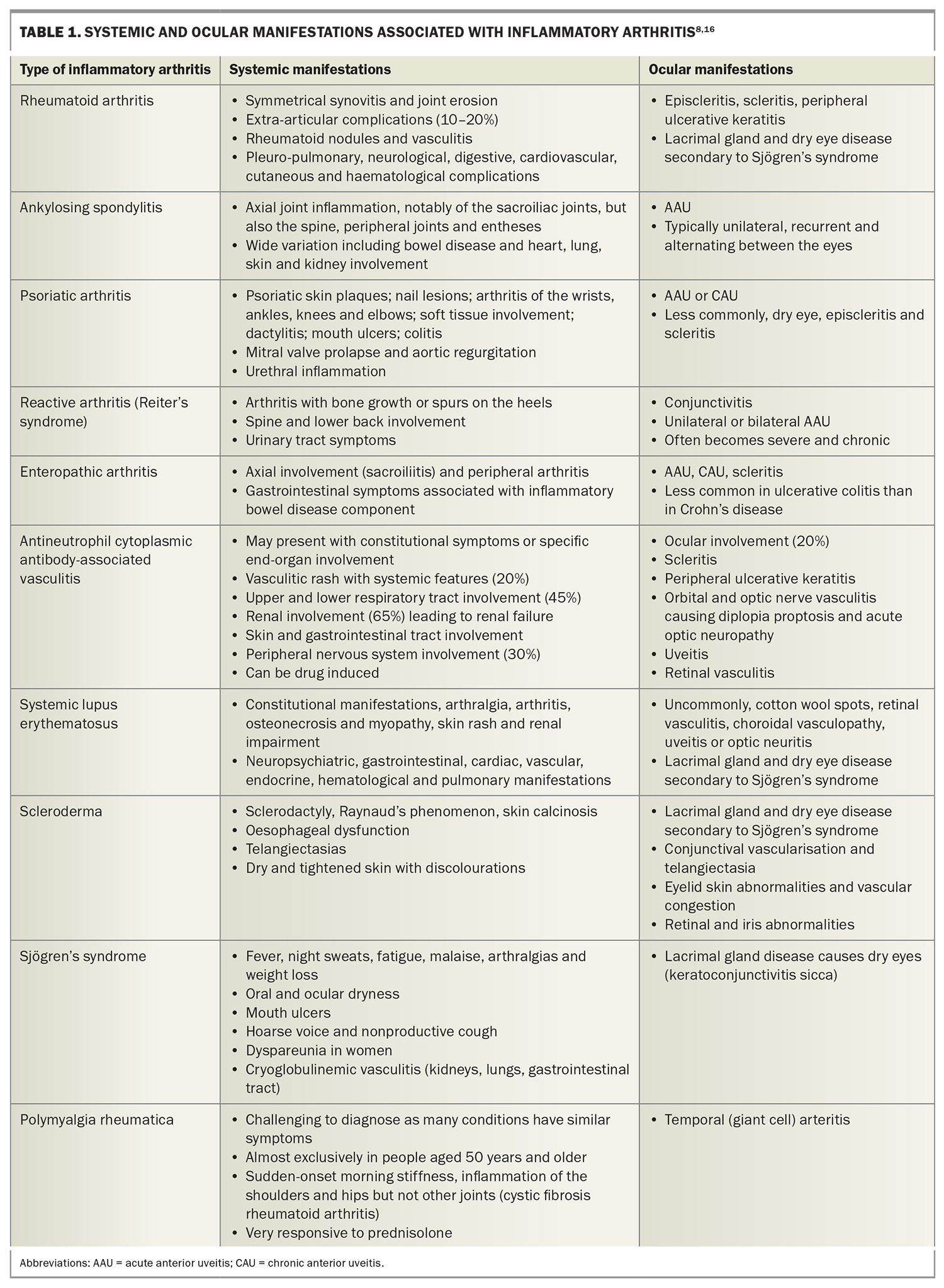

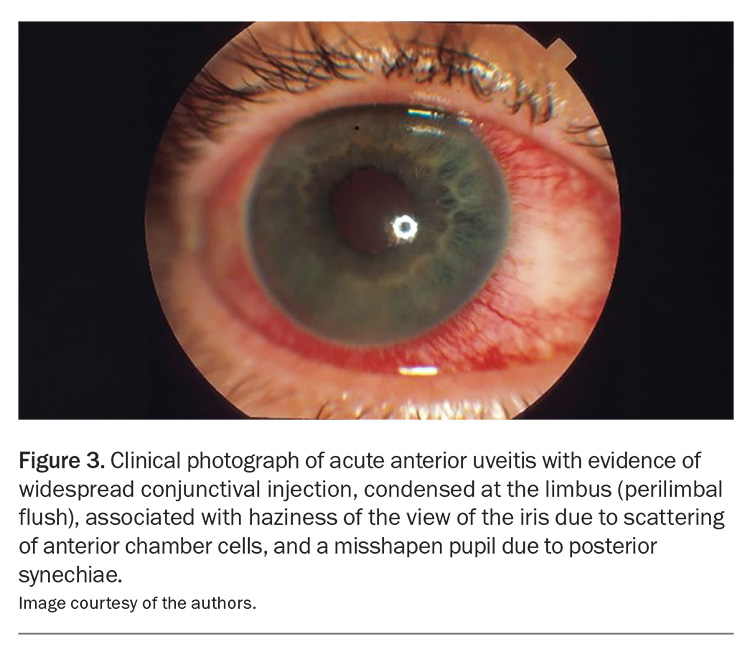

Ocular complications occur in an estimated 25 to 40% of patients with inflammatory arthritis.14,15 Ocular involvement in inflammatory arthritis can affect almost any structure of the eye and patients may present with diverse clinical manifestations. Understanding the anatomy of the eye (Figure 2) and the spectrum of ocular complications associated with inflammatory arthritis is important for the early recognition, prompt intervention and appropriate referral of patients to an ophthalmologist. Systemic and ocular manifestations associated with inflammatory arthritis are listed in Table 1.8,16

The most commonly affected ocular tissues include the uvea (uveitis or iritis), sclera (scleritis), episclera (episcleritis), cornea (keratitis), ocular surface and lacrimal gland (dry eye). AAU is the most frequent ocular complication, occurring predominantly in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis (Figure 3).

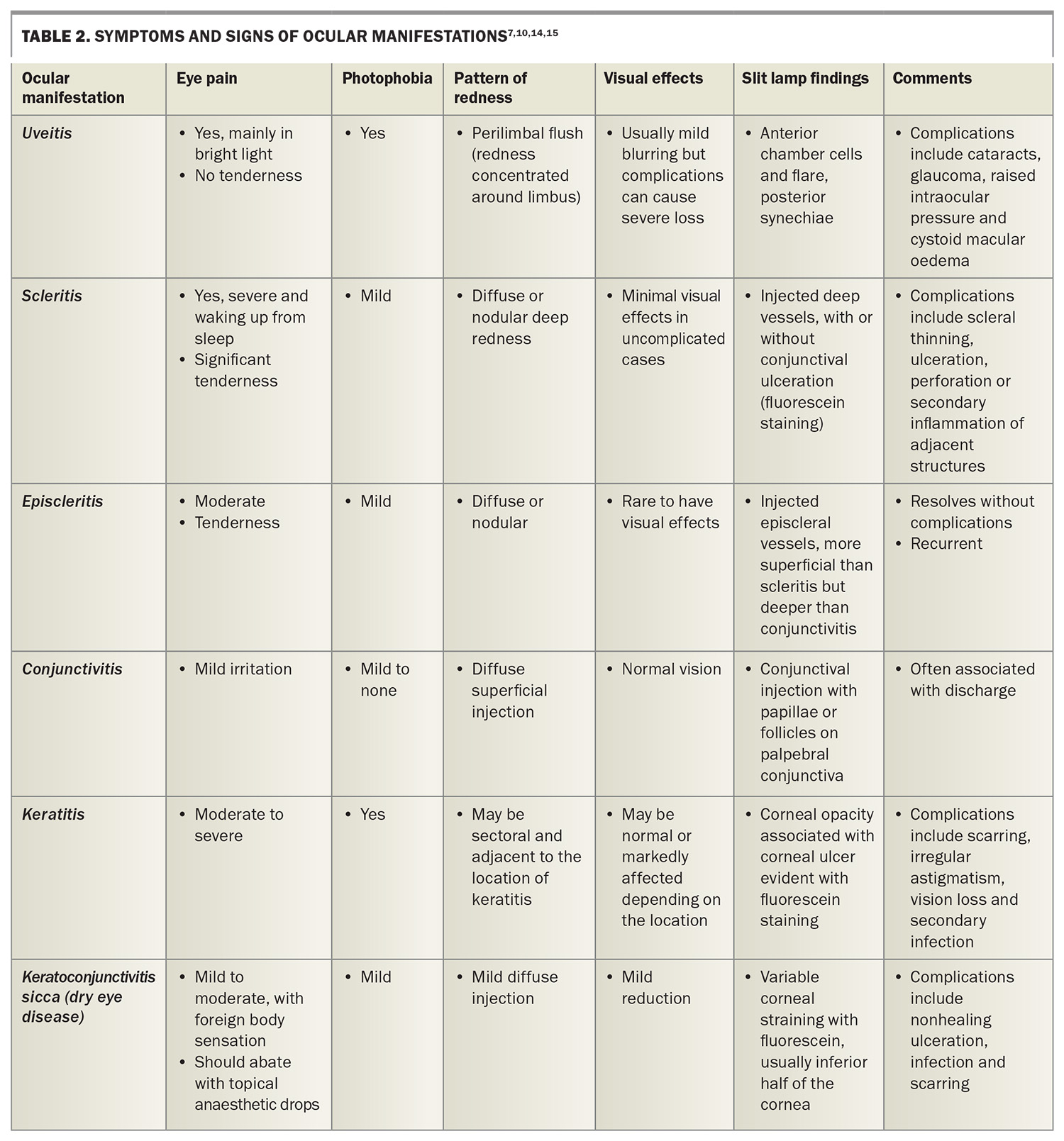

Scleritis is the classic ocular manifestation of RA, although it is becoming less common because of the use of modern biologic therapy. The presenting symptoms and signs of each of these ocular manifestations are presented in Table 2.7,10,14,15

Ocular manifestations associated with RA include keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eye disease), episcleritis, scleritis, keratitis and retinal vasculitis.5,6 These manifestations may also occur in other types of inflammatory arthritis.

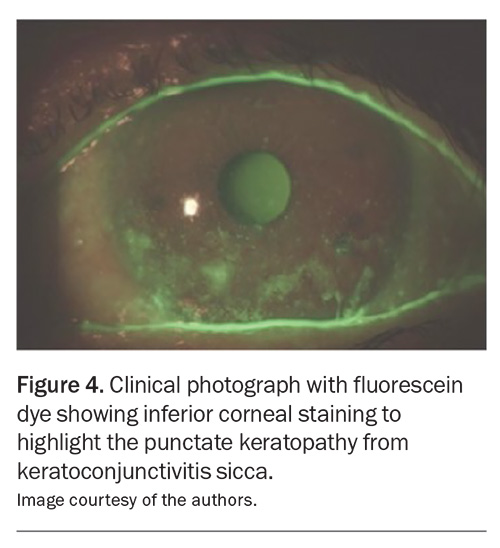

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

Keratoconjuctivitis sicca, also known as a type of dry eye disease, results from aqueous tear deficiency (Figure 4).5,7,17

Common ocular manifestations of RA include corneal inflammation, lacrimal gland dysfunction and corneal ulceration, broadly sharing similar pathogenic mechanisms to those of dry eye disease.17 The association between RA and dry eye disease is not fully elucidated,17 but dry eye is reported in 10 to 50% of patients.5 Patients complain of burning, foreign body sensation, intermittent blurred vision, variable redness and photophobia.7

The use of unpreserved artificial tear substitutes and punctal plugs are usually necessary for management. Topical cyclosporine A can also be helpful by inhibiting inflammatory cytokine production seen on the ocular surface.7 Autologous and allogeneic serum eye drops are very useful for severe dry eye disease.

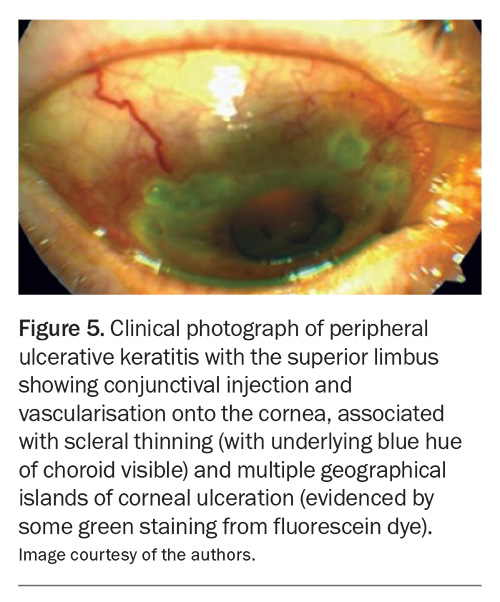

Keratitis

RA uncommonly affects the peripheral cornea, with corneal thinning and inflammation. This is known as peripheral ulcerative keratitis, which refers to crescent-shaped destructive inflammation of the juxtalimbal corneal stroma associated with an epithelial defect and the presence of stromal inflammatory cells, with stromal degradation and progressive tissue loss and perforation (Figure 5).7

The corneal ulceration will be evident with fluorescein staining and cobalt blue light. Patients with peripheral ulcerative keratitis frequently present with pain, tearing and photophobia.7 The mainstay of treatment is controlling the underlying systemic vasculitis with systemic immunosuppressive therapy.7 The severity of these ocular complications highlights the importance of urgent ophthalmological examinations in patients with RA who present with significant ocular symptoms, such as acute vision loss or pain.17

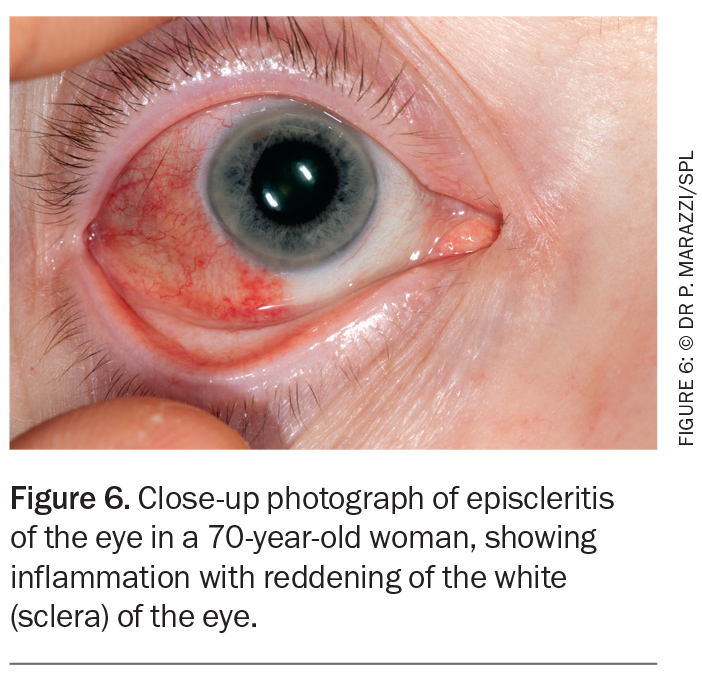

Episcleritis

Episcleritis involves inflammation of the superficial layers of the sclera and its more superficial episcleral tissue and conjunctiva.7 It presents as a relatively asymptomatic, acute-onset vascular injection in one or both eyes (Figure 6).7 Other symptoms include pain, photophobia and watery discharge. Most cases are self-limiting, but some patients require treatment with topical lubricants, NSAIDs or topical corticosteroids.7 Systemic NSAIDs may be useful.7 It is important to differentiate between scleritis and episcleritis because the treatment, prognosis and systemic associations differ markedly.18 If the diagnosis is uncertain, referral to an ophthalmologist is indicated.

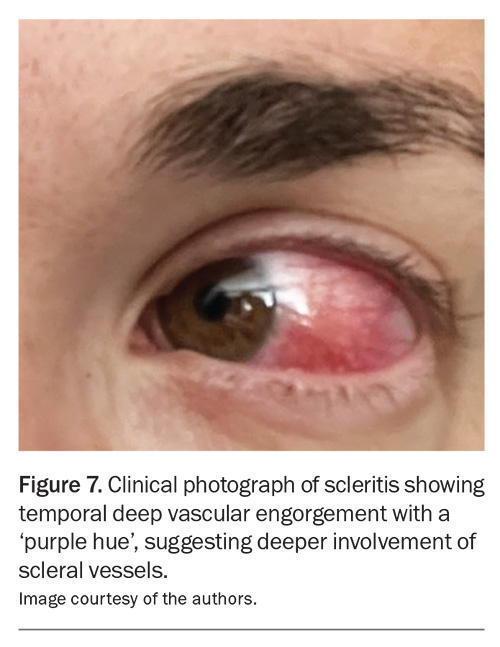

Scleritis

Scleritis is a rare, chronic, painful and potentially blinding inflammatory disease that is characterised by oedema and inflammatory cellular infiltration of the scleral and episcleral tissues.5 It is classified into anterior and posterior scleritis. Anterior scleritis is painful and potentially blinding, and patients can present with a red eye and characteristic violet-bluish hue, along with scleral oedema and dilatation of blood vessels (Figure 7).19 The characteristic symptom is severe pain that typically wakes patients from their sleep early in the morning.

Anterior scleritis can be diffuse, nodular, necrotising with inflammation (necrotising scleritis) or necrotising without inflammation (scleromalacia perforans).5,7 The most common forms are diffuse scleritis and nodular scleritis.7 Necrotising scleritis is much less frequent, more ominous and associated with systemic vasculitis. Scleromalacia perforans is a rare form of necrotising anterior scleritis seen in patients with RA, characterised by progressive thinning of the sclera without significant redness or pain. It has largely disappeared with the use of modern RA therapy.7

Scleritis is often associated with systemic disease in up to 50% of patients, with the most common rheumatological diseases being RA, AAV and SpA.18 RA is the cause of 8 to 15% of scleritis cases, and about 2% of patients with RA develop scleritis.19

Posterior scleritis is characterised by flattening of the posterior aspect of the globe, thickening of the choroid and sclera posteriorly, and retrobulbar oedema. Patients may present with a white eye, but severe retrobulbar pain, especially on eye movement.7 A ‘T-sign’ may be seen on ocular ultrasound.20 Posterior scleritis is a significant threat to vision because of the spillover of inflammation involving the macula, optic disc and retina.7

Retinal vasculitis

Retinal vasculitis is an uncommon but serious potential threat to vision in patients with inflammatory arthritis. It usually occurs in patients with AAV, SLE or Behçet’s disease. It can involve the central or peripheral retina and involve arteries or veins. Patients present with decreased visual acuity, visual floaters, scotomas, a decreased ability to distinguish colours and metamorphopsia.7 Severe retinal vasculitis requires aggressive systemic combination immunosuppressive therapy with corticosteroids and immunomodulatory therapy.7

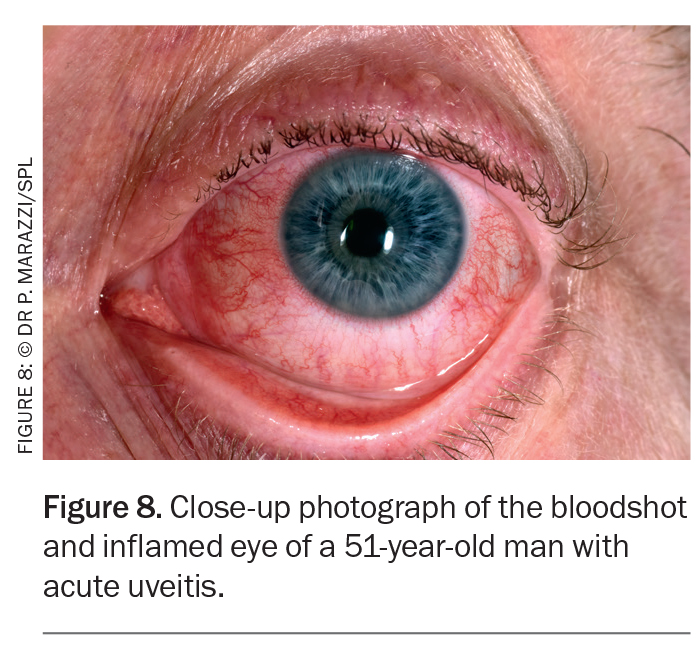

Uveitis

Uveitis is the most frequent extra-articular manifestation of spondyloarthritis, ranging from 21 to 33% in meta-analyses.15 About two-thirds of patients with AAU in association with spondyloarthropathy are unaware that they have a spondyloarthropathy; as such, it may be the presenting feature.21 The frequency is much greater in association with ankylosing spondylitis than with either inflammatory bowel disease or psoriasis.22 Patients with HLA-B27-associated uveitis may rarely develop vision-threatening posterior segment manifestations.23

The phenotype of uveitis characteristic of ankylosing spondylitis (and HLA-B27-positive status) is sudden onset, anterior only, unilateral, more common in men than in women, of limited duration and recurrent.22 Pain, photophobia and blurred vision are caused by ciliary spasm in response to anterior chamber inflammation (Figure 8).14 It is common to see circumcorneal injection and keratic precipitates with a hypopyon in some cases, which may resemble an intraocular infection.24 Persistence of uveitis leads to posterior synechiae (adhesions between the iris and lens) and, as such, the pupil may not dilate and constrict properly.24

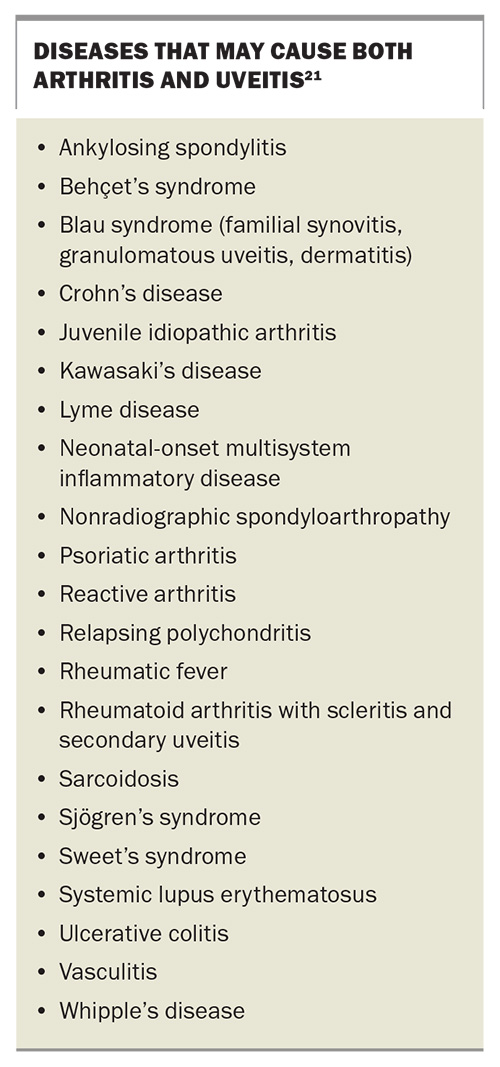

The presence or absence of uveitis may affect the choice of systemic therapy. Monoclonal antibodies that neutralise TNF, such as adalimumab and golimumab, consistently reduce the incidence and severity of AAU.21,24 In patients with joint disease that is not sufficiently severe to warrant a biologic, sulfasalazine offers an excellent alternative strategy for prevention of AAU.25 Uveitis can also rarely be a complication of therapies such as intravenous bisphosphonates, rifabutin and checkpoint inhibitors.22,26 Any patients suspected of having uveitis should be referred to an ophthalmologist, as complications such as glaucoma, cataracts and macular oedema often lead to severe vision impairment or blindness.2 Diseases that may cause both arthritis and uveitis are listed in the Box.21

Ocular complications associated with AAV

About one-fifth of patients with AAV have inflammatory ocular manifestations.11 These can occur in the absence of systemic disease.27 In one study, patients with ocular involvement experienced a 2.75-fold higher mortality rate than patients with other inflammatory eye diseases.28 Lung or kidney involvement also confers a poorer prognosis and higher mortality.11

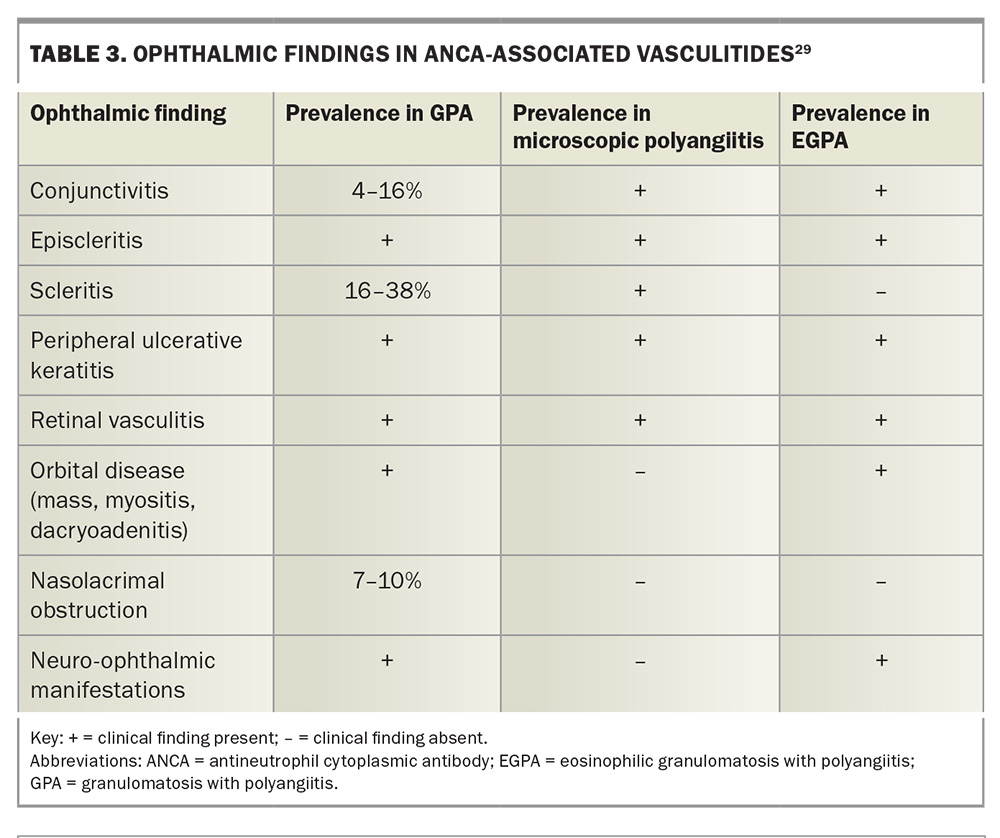

Scleritis and episcleritis are the most common ocular manifestations, with orbital inflammation (inflammatory orbital pseudotumour or orbital myositis), uveitis, conjunctivitis, dacryoadenitis or dacryocystitis, peripheral ulcerative keratitis, cranial nerve palsy (III, IV or VI) and retinal vasculitis also being common.11 In one study, about one-quarter of patients experienced at least one relapse.11

Orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumour)

Orbital involvement is one of the most common presentations of GPA, reported in 15 to 60% of cases, and can be bilateral in 14 to 58% of cases.27 Contiguous sinus involvement is common.11 This results in swelling of the eyelids, epiphora, proptosis, restricted eye movements with diplopia and visual distortion.29 Orbital involvement in EGPA may present as dacryoadenitis (inflammation of the lacrimal gland) or myositis.

Orbital pseudotumours have a significant risk of vision impairment or blindness despite aggressive treatment, with retrobulbar granulomatous masses compressing the optic nerve and vessels, or even destruction of orbital bone.27 Imaging modalities such as CT or MRI are helpful in characterising the size, extent and treatment response of orbital lesions, as well as excluding differential diagnoses and assessing the risk of optic nerve entrapment.27

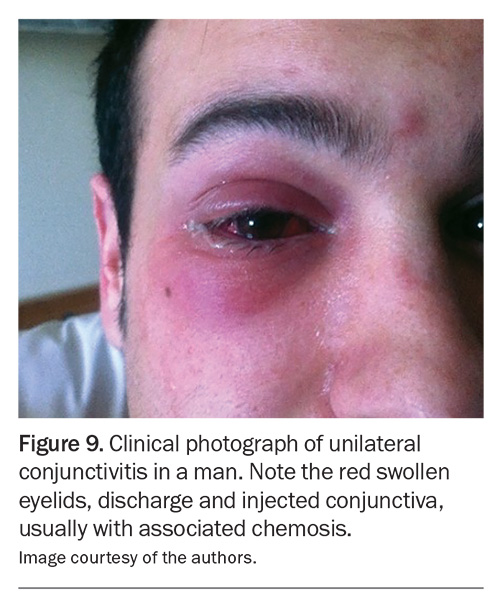

Conjunctival, episcleral and scleral diseases

Conjunctival, episcleral and scleral manifestations can be difficult to distinguish from each other, as they all present with ocular redness and discomfort.29 The key is to distinguish the depth of tissue involvement, which requires further specialist assessment.

Conjunctivitis is common and may be ulcerative, necrotic or cicatricial (Figure 9).27 It is usually bilateral, and the symptoms include ocular redness, foreign body sensation, blurred vision and, occasionally, bloody tears.27 Cicatrising conjunctivitis may result in conjunctival scarring, leading to shortened fornices or symblepharon (bands stretching across the ocular surface to the eyelids).27,29

Episcleritis presents with unilateral or bilateral ocular redness, and may be diffuse, sectoral or nodular in presentation. The clinical course is similar to that of episcleritis associated with RA or SpA.

Scleritis, as discussed above, presents with deep, boring pain and photophobia and can be necrotising with scleral thinning and perforation. Severe ocular complications occur in more than 90% of patients, often resulting in vision impairment or blindness.29 As per scleritis in other types of inflammatory arthritis, it requires early recognition, aggressive systemic immunosuppression and, occasionally, surgery.

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis is the most important corneal complication of AAV, and is the result of immune-mediated obstructive necrotising vasculitis of the anterior ciliary arteries.29 Lesions are usually found within 2 mm of the corneoscleral limbus and are often accompanied by necrotising scleritis.29 The corneal stroma may perforate either spontaneously or with minor ocular trauma in up to one-third of patients.29 Topical antibiotic coverage for corneal epithelial breakdown and aggressive tear replacement should be initiated.29 Oral doxycycline, which inhibits matrix metalloproteinase activity, can be helpful in limiting corneal melting.27,29

Retinal involvement

Retinal involvement is uncommon and includes cotton wool spots, retinal vasculitis, retinal haemorrhages, retinitis, macular oedema, central retinal artery or vein occlusion and exudative retinal detachment.10,27 The most common presenting symptoms are blurry vision and floaters.27 Urgent referral for ocular imaging studies such as fluorescein angiography is essential.27 Treatment is complex and often includes intraocular injections of antivascular endothelial growth factor and pan-retinal laser photocoagulation.27

Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations

Diplopia or vision loss from optic neuropathy is most commonly caused by infiltration of orbital structures and mass effect, but vasculitis affecting the blood vessels supplying the orbital cranial nerves or optic nerve can also cause these findings.29 Ischaemic optic neuropathy has been reported in GPA and EGPA, and these patients present with acute painless loss of vision with an afferent pupillary defect, optic nerve oedema and visual field loss.29 Palsies of the oculomotor, trochlear and abducens cranial nerves have been reported in GPA and EGPA (Table 3).29

Management

Management of ocular complications in inflammatory arthritis requires a multidisciplinary approach involving GPs, rheumatologists and other medical specialists, such as ENT surgeons, immunologists and neurologists, in addition to ophthalmologists. Treatment strategies aim to control both systemic and ocular inflammation, to prevent disease progression and preserve vision. Local therapy is often insufficient to control ocular conditions, and systemic immunosuppression may be required. Our increasing understanding of autoimmune and autoinflammatory disorders has resulted in improved, more targeted therapy, with strategies targeting cytokines being effective in autoinflammatory and autoimmune disease, and strategies targeting B-cells being effective in vasculitis (Figure 10).4

Topical therapy

The standard treatment approach for symptomatic relief of an acute attack of uveitis is a cycloplegic agent (e.g. atropine 1% twice daily) with intensive topical corticosteroids (e.g. prednisolone acetate 1%).24 Corticosteroids can also be used systemically, or by local injection, such as a subconjunctival injection. Cycloplegia controls ciliary spasm, thereby reducing pain, but also minimises the formation of posterior synechiae.24

NSAIDs

NSAIDs may provide symptomatic relief for episodes of mild ocular surface inflammation, such as episcleritis, but are insufficient for controlling severe inflammation.24 Care needs to be taken to avoid corneal melting.24 Systemic NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandins and are used in mild conditions and if inflammation has been nonresponsive to topical therapy.24

Corticosteroids

Topical, periocular, intravitreal and systemic corticosteroids are often used to acutely suppress ocular inflammation, but their long-term use carries risks of adverse effects. The most commonly documented, vision-threatening side effects include cataracts, glaucoma and an increased risk of infection (commonly, microbial keratitis and herpes simplex keratitis). Systemic glucocorticoids (such as prednisolone) are administered when topical treatment is ineffective and especially for bilateral uveitis.24

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

Medications such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine, cyclosporin, mycophenolate, azathioprine and biologic agents targeting TNF-α, IL-6 or IL-17 have shown efficacy in managing both joint symptoms and ocular manifestations in patients with inflammatory arthritis. Methotrexate has been shown to decrease the rate of AAU flares during withdrawal of systemic corticosteroids.30 Sulfasalazine, leflunomide, azathioprine and cyclosporine have also shown some efficacy in the treatment of noninfective uveitis, including intermediate and posterior uveitis.30

Newer biologic agents are very effective in treating several rheumatic diseases and their ocular manifestations. TNF antagonists including infliximab and adalimumab have been reported to reduce the frequency of AAU.24 Infliximab has been found to be more effective than etanercept in treating uveitis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.31 Stopping treatment with TNF inhibitors results in rapid relapse for most patients with longstanding inflammatory arthritic disease, especially SpA.32 Paradoxically, etanercept increases the risk of developing uveitis; if a patient develops uveitis, changing to another biologic is necessary.31

Induction therapy with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide has traditionally been used in AAV, improving survival in GPA from 10 to 80%.27 AAV remission is similarly high with rituximab therapy and may be superior in recurrent disease.33

Effective therapies and therapeutic targets for immunological diseases are listed in Table 4.3

Conclusion

Inflammatory arthridities often cause ocular manifestations, and these can involve virtually any ocular or adnexal structure. Ocular involvement is often severe and vision-threatening, as well as being the first sign of possible systemic disease. Clinicians must be able to recognise ocular symptoms and findings on examination as being indicators of a serious underlying systemic disease so that appropriate systemic workup can be initiated. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Ciccarelli F, De Martinis M, Ginaldi L. An update on autoinflammatory diseases. Curr Med Chem 2014; 21: 261-269.

2. CreakyJoints Australia – Classifications of Arthritis. Available online at: https://creakyjoints.org.au/education/classifications_of_arthritis/ (accessed November 2024).

3. McGonagle D, McDermott MF. A proposed classification of the immunological diseases. PLoS Med 2006; 3: e297.

4. Generali E, Bose T, Selmi C, Voncken JW, Damoiseaux JGMC. Nature versus nurture in the spectrum of rheumatic disease: classification of spondyloarthritis as autoimmune or autoinflammatory. Autoimmun Rev 2018; 17: 935-941.

5. Zlatanovic G, Veselinovic D, Cekic S, Zivkovic M, Dordevic-Jocic J, Zlatanovic M. Ocular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis - different forms and frequency. Bosnian J Basic Med Sci 2010; 10: 323-327.

6. Turk MA, Hayworth JL, Nevskaya T, Pope JE. Ocular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis, connective tissue disease, and vasculitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rheumatol 2021; 4: 25-34.

7. Lamba N, Lee S, Chaudhry H, Foster CS. A review of the ocular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Cogent Med 2016; 3: 1-5.

8. Hunter RW, Farrah TE, Dhaun N. ANCA-associated vasculitis. BMJ 2020; 369: m1070.

9. Junek ML, Zhao L, Garner S, et al. Ocular manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheumatol 2023; 62: 2517-2524.

10. Simion MS, Alexandra K. Eye involvement in ANCA-positive vasculitis. Romanian J Ophthalmol 2020; 64: 3-7.

11. Ungprasert P, Crowson CS, Cartin-Ceba R, et al. Clinical characteristics of inflammatory ocular disease in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis: a retrospective cohort study. Rheumatol 2017; 56: 1763-1770.

12. Lyons PA, Rayner TF, Trivedi S, et al. Genetically distinct subsets within ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 214-223.

13. Muhammad H, O’Rourke M, Ramasamy P, Murphy CC, FitzGerald O. A novel evidence-based detection of undiagnosed spondyloarthritis in patients presenting with acute anterior uveitis: the DUET (Dublic Uveitis Evaluation Tool). Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 1990-1995.

14. Patel SJ, Lundy DC. Ocular manifestations of autoimmune disease. Am Fam Physician 2002; 66: 991-998.

15. Rademacher J, Poddubnyy, Pleyer U. Uveitis in spondyloarthritis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2020; 12: 1-20.

16. Rosenbaum JT, Dick AD. The eyes have it: a rheumatologist’s view of uveitis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; 70: 1533-1543.

17. Lai S, Wang C, Wu Y, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis associated with dry eye disease and corneal surface damage: a nationwide matched cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023; 20: 1584.

18. Bacchiega A, Balbi G, Ochtrop M, Assis de Andrade F, Levy R, Baraliakos X. Ocular involvement in patients with spondyloarthritis. Rheumatol 2017; 56: 2060-2067.

19. Promelle V, Goeb V, Gueudry J. Rheumatoid arthritis associated episcleritis and scleritis: an update on treatment perspectives. J Clin Med 2021; 10: 2118.

20. Schwartz TM, Keenan RT, Daluvoy MB. Ocular involvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Eyenet magazine: Ophthalmic Pearls Nov 2016. Available online at: https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/ocular-involvement-in-rheumatoid-arthritis?november-2016 (accessed November 2024).

21. Rosenbaum JT. The eye in spondyloarthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2019; 49 (3 Suppl): S29-S31.

22. Rosenbaum JT. Uveitis in spondyloarthritis including psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Rheumatol 2015; 34: 999-1002.

23. Or C, Lajevardi S, Ghoraba H, et al. Posterior segment ocular findings in HLA-B27 positive patients with uveitis: A retrospective analysis. Clin Ophthalmol 2023; 17: 1271-1276.

24. Pandey A, Ravindran. Ocular manifestations of spondyloarthritis. Mediterr J Rheumatol 2023; 34: 24-29.

25. Ward MM. Sulfasalazine for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: Relic or niche medication? Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63: 1472-1474.

26. Lim LL, Fraunfelder FW, Rosenbaum JT. Do tumour necrosis factor inhibitors cause uveitis? A registry-based study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2007; 56: 3248-3252.

27. Tekin MI, Ozdal MP. Ophthalmic manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Acta Medica 2021; 52: 257-263.

28. Watkins AS, Kempen JH, Dongseok C, et al. Ocular disease in patients with ANCA-positive vasculitis. J Ocul Biol Dis Infor 2009; 3: 12-19.

29. Kubal AA, Perez VL. Ocular manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 2010; 36: 573-586.

30. Gomez-Gomez A, Loza E, Rosario MP, et al. Efficacy and safety of immunomodulatory drugs in patients with anterior uveitis: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96: e8045. 2018; 12: 2005-16.

31. Ming S, Xie K, He H, Li Y, Lei B. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in the treatment of non-infectious uveitis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Drug Des Devel Ther 2018; 12: 2005-2016.

32. McVeigh CM, Cairns AP. Diagnosis and management of ankylosing spondylitis. BMJ 2006; 333: 581-585.

33. Jones RB, Tervaert JW, Hauser T, et al. Rituximab versus cyclophosphamide for ANCA-associated vasculitis. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 221-232.