A diagnostic approach to arthritis

Arthritis is a common chronic condition and a major contributor to illness, pain and disability. There are many forms of arthritis, but the pattern of joint involvement may help clinicians determine the cause of symptoms. Findings that suggest an inflammatory cause or red flags for septic arthritis should trigger early escalation of care. Prompt diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment will notably improve patient outcomes.

- Septic arthritis is a medical emergency that should be suspected in patients with acute-onset joint swelling and pain with associated systemic symptoms.

- All forms of arthritis can cause stiffness, but diurnal variation and stiffness that lasts longer than 30 to 60 minutes after periods of inactivity indicate a likely inflammatory cause.

- A global ‘autoimmune screen’ should not be performed, with only relevant immunological tests ordered when there is a reasonable pretest probability.

- Inappropriate testing leads to delays in appropriate patient care. Repeating immunological tests where results were previously negative is not recommended.

- Negative rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide findings do not exclude inflammatory arthritis.

- Joint aspiration and appropriate imaging can aid with assessment of joint conditions.

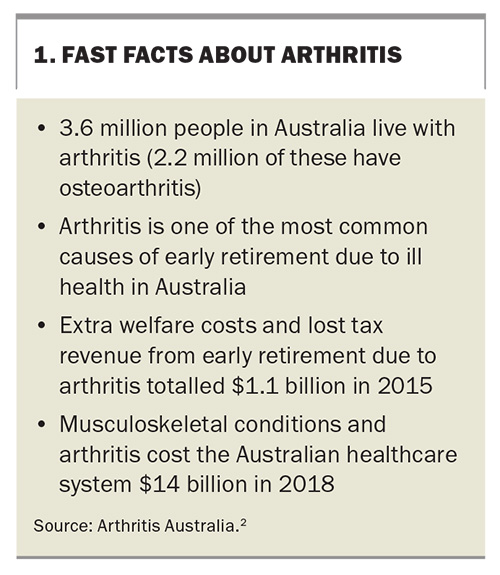

Arthritis is a blanket term that covers several different conditions of the joints, including rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and gout. Arthritis is one of the most prevalent chronic conditions in Australia, with one in three Australians (29%) reporting a musculoskeletal condition, and 3.6 million (15%) reporting a form of arthritis, in 2017-2018 (Box 1).1,2

Arthritis is a major contributor to illness, pain and disability. People with arthritis report poorer productivity, lost opportunities to participate in the workplace, cognitive impacts, poorer mental health and other health complications, such as an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with gout or poorly controlled inflammatory arthritis.1-3

Septic arthritis

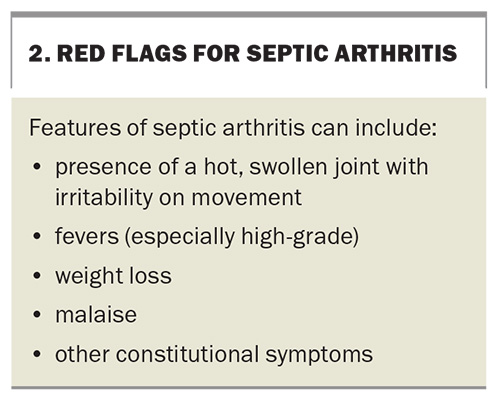

Septic arthritis is a medical emergency. It should be suspected in patients with acute-onset joint swelling and pain with associated systemic symptoms. Suspicion should increase if there are relevant risk factors, including bacteraemia, history of pre-existing joint disease, recent use of medical instruments, intravenous drug use or immunosuppression.

However, there are other conditions that might cause a painful monoarthritis (e.g. crystal arthritis, reactive arthritis and trauma), some of which, such as crystal- associated arthropathies, can present with fever and constitutional features. The diagnosis of septic arthritis is therefore based on synovial fluid aspiration and culture. Synovial fluid aspiration and blood cultures should be performed before starting antibiotics in patients with suspected septic arthritis.

Red flags – features that indicate prompt consideration of septic arthritis and escalation of care – are shown in Box 2. Patients in the community with suspected septic arthritis should be referred promptly to a hospital with orthopaedic services, either via the emergency department or through an arranged direct admission.

Clinical assessment

Clinical assessment of arthritis relies on detailed history taking, with a focus on the distribution and duration of joint disease, followed by clinical examination, particularly of the joints and skin.

History

The symptoms of osteoarthritis, which is noninflammatory, tend to develop gradually over time, whereas the presentation of inflammatory arthritis is variable and can be gradual or acute in onset. Viral arthritis mostly resolves within 12 weeks of symptom onset, whereas inflammatory arthritis will persist beyond this.4

Although pain is a common feature of all forms of arthritis, diurnal variation and aggravating and relieving factors can help differentiate the cause. Pain that is worse in the morning or after periods of inactivity, with associated features like joint swelling and stiffness, suggests an inflammatory aetiology. In contrast, pain from osteoarthritis typically worsens as the day progresses and with activity but improves with rest.

Patients will often report some degree of stiffness with their arthritis, even if their disease is noninflammatory, as with osteoarthritis. In noninflammatory arthritis, the stiffness is often transient and short-lived. Stiffness lasting more than 30 to 60 minutes is more suggestive of an inflammatory arthritis.

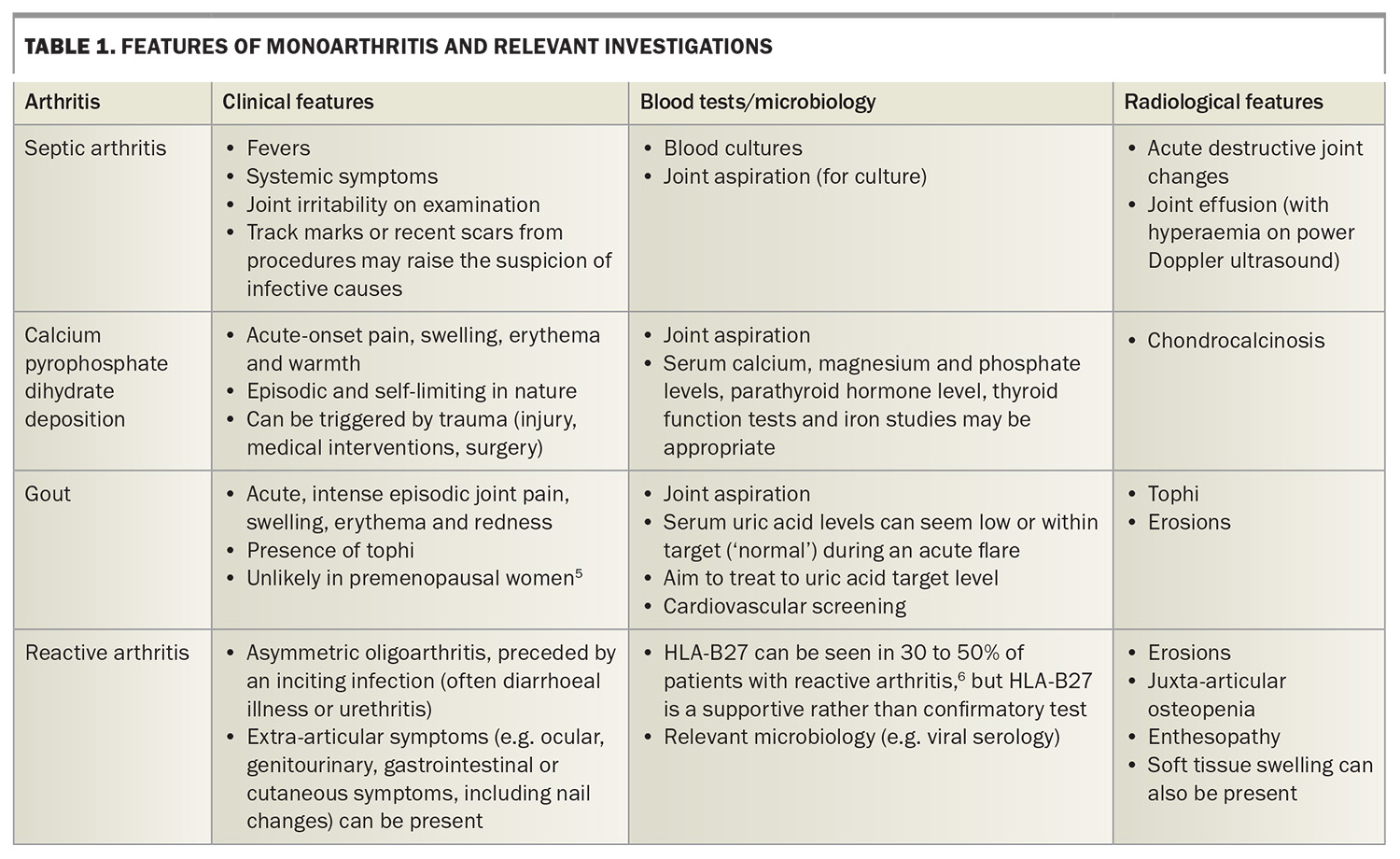

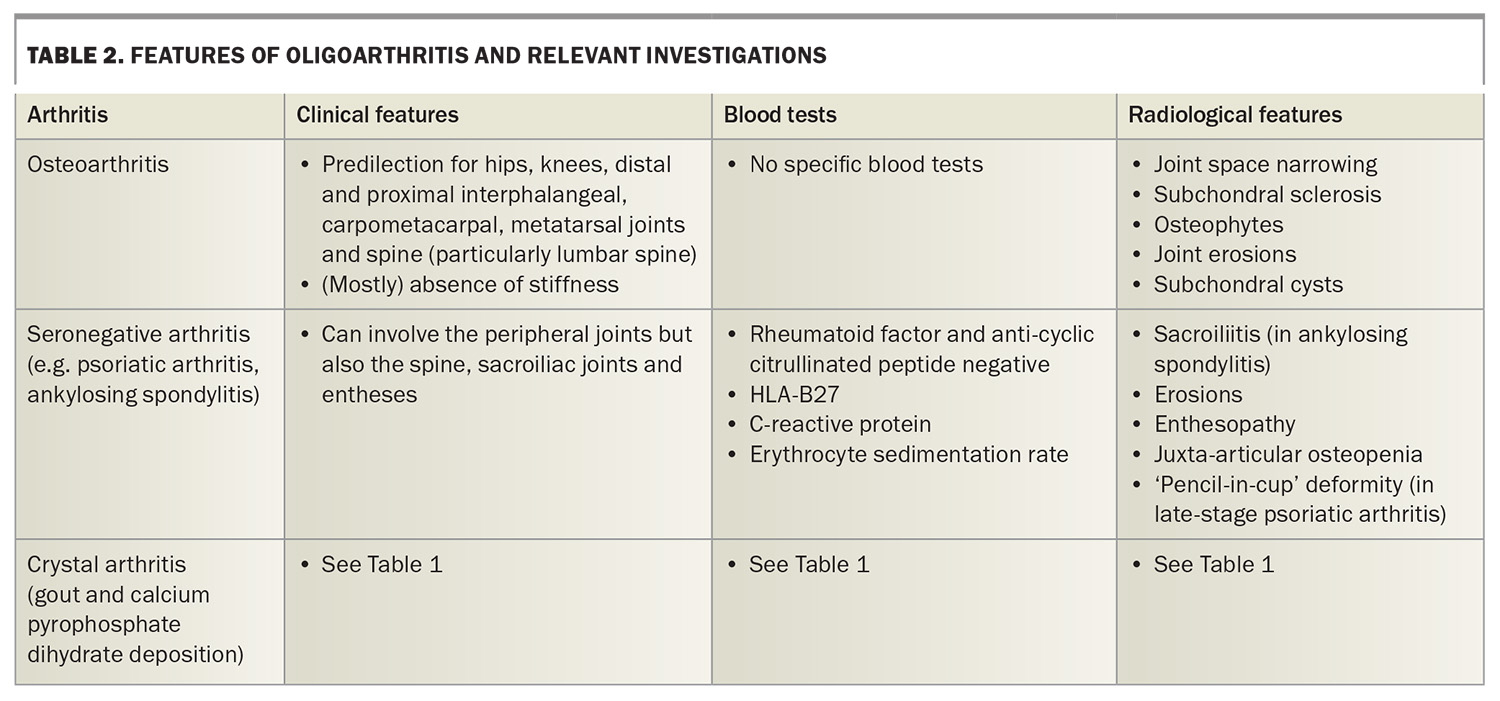

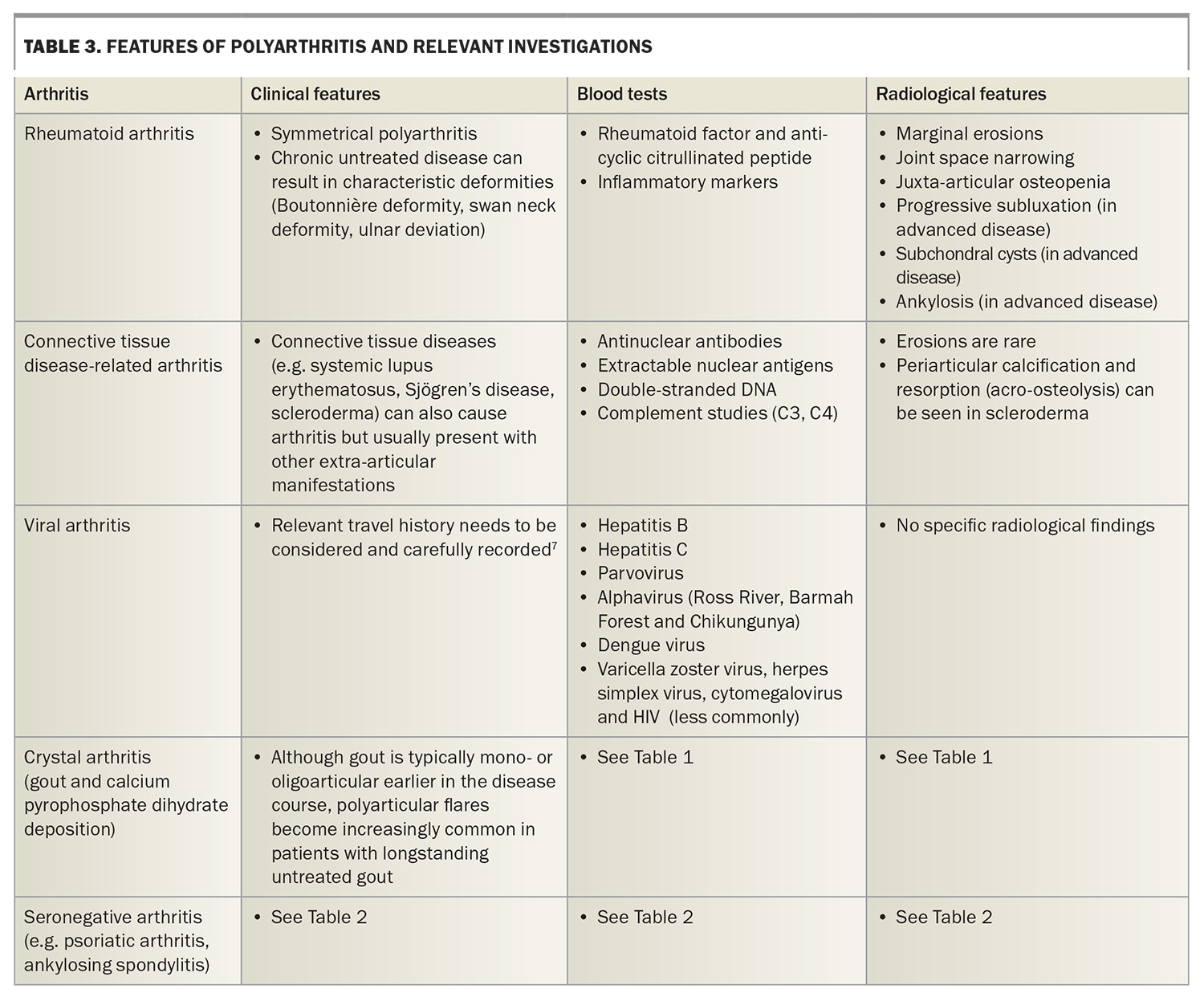

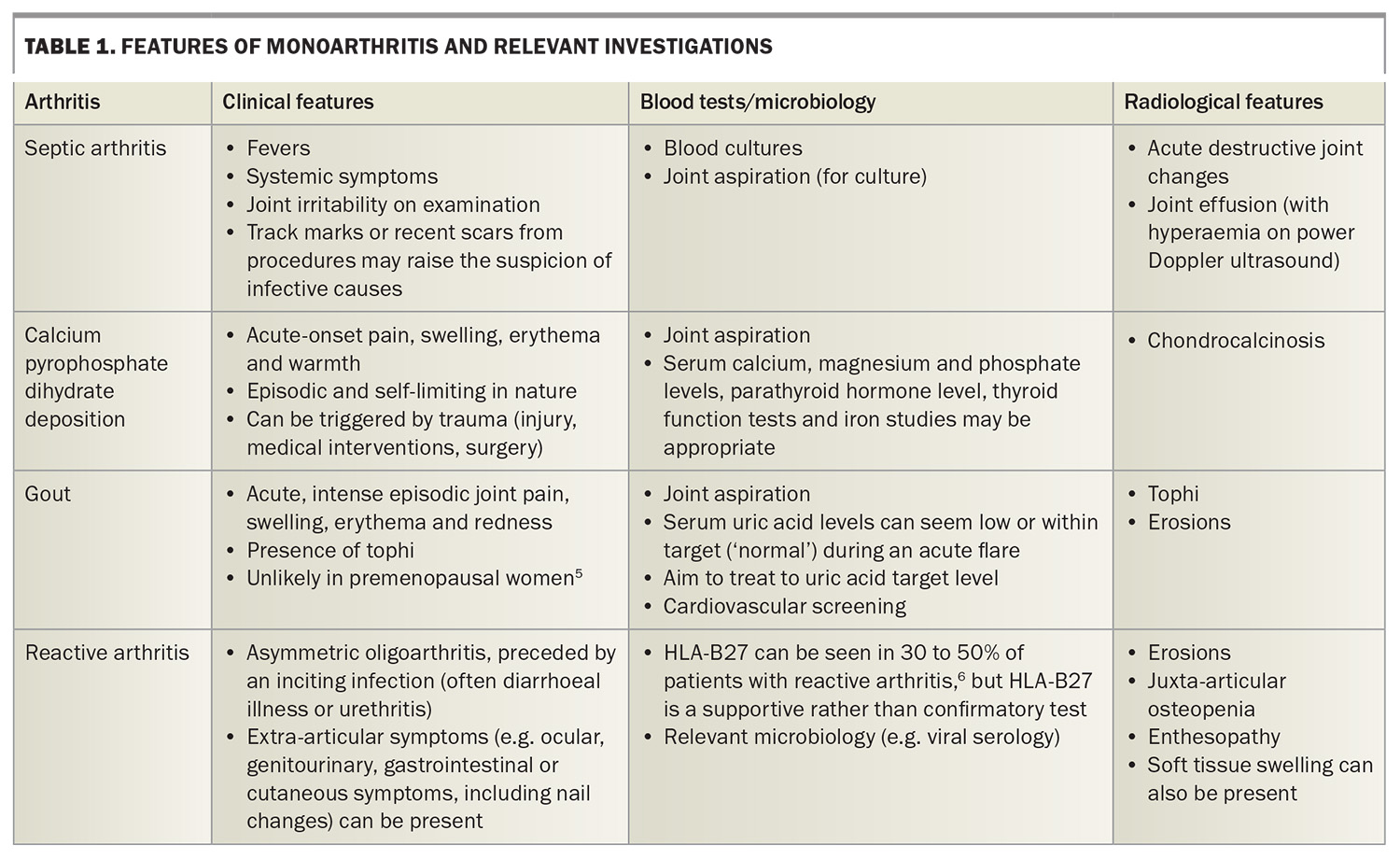

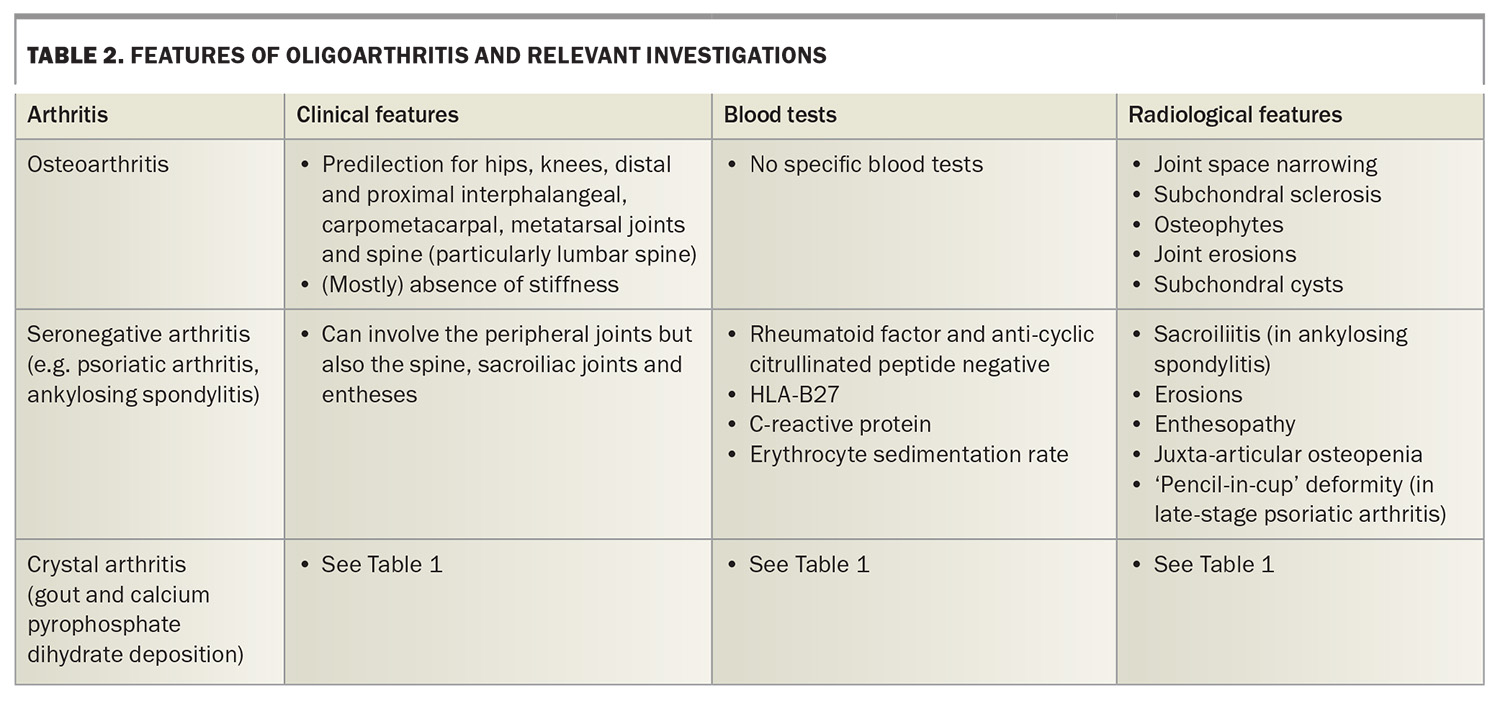

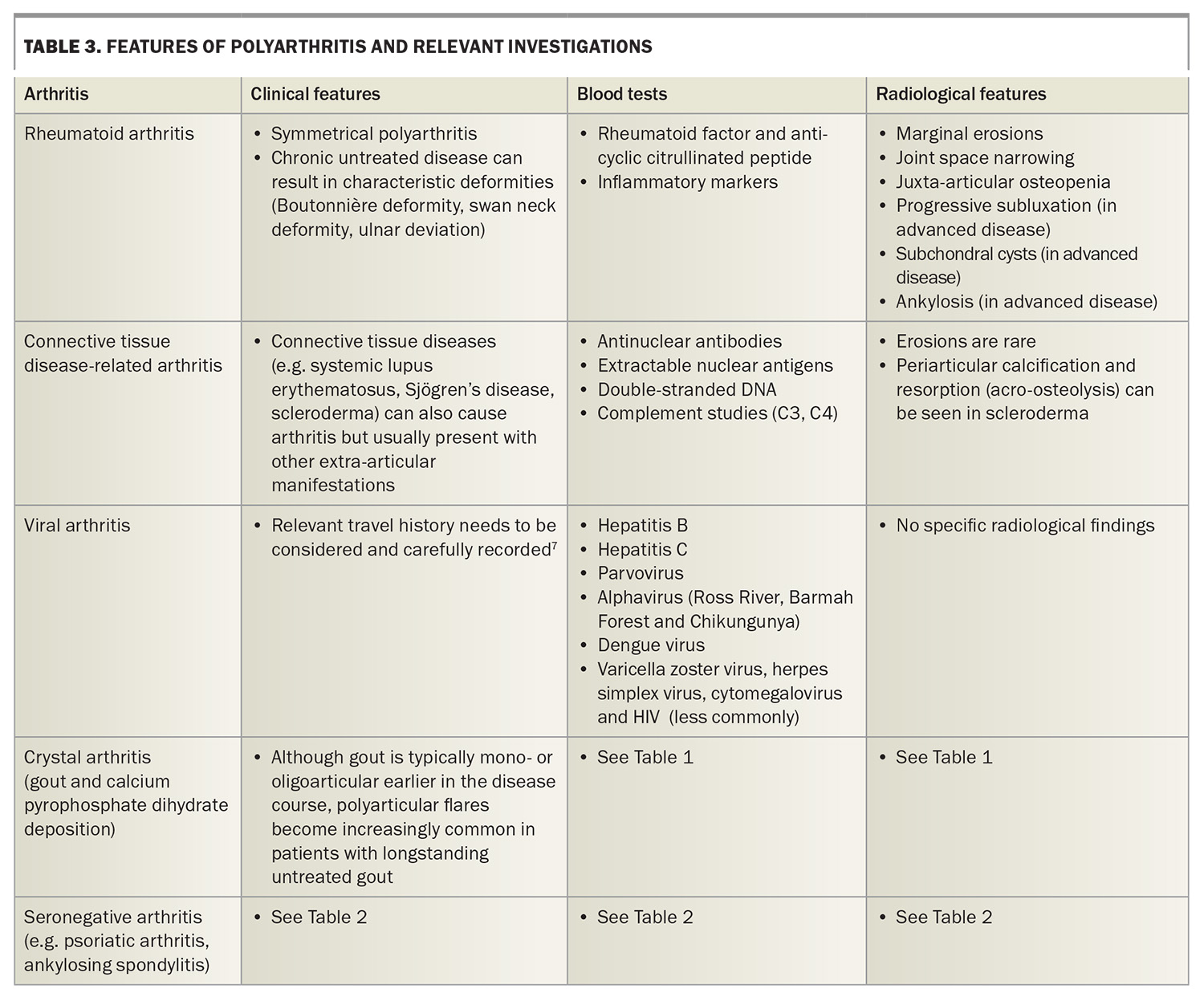

The pattern of joint involvement may help clinicians to determine the cause of symptoms. For example, a symmetrical polyarthritis may represent rheumatoid arthritis, whereas a recurrent monoarthritis with crystals detected in aspirate would be caused by crystal arthritis. Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 show different types of arthritis by pattern of joint involvement.5-7

Review of associated extra-articular features is helpful and may provide clues to the cause of a patient’s joint pains. A psoriatic rash or presence of a red eye suggestive of inflammatory eye disease may point towards spondyloarthropathies. In patients with psoriatic arthritis, 72% have been shown to have cutaneous psoriasis precede arthritis by an average of seven to eight years.8 The presence of a photosensitive rash with nasolabial sparing, recurrent ulcers and alopecia may suggest an underlying connective tissue disease. Often, extra-articular features do not occur simultaneously, but serial reviews may show suspicious symptoms that help guide further diagnostic evaluation.

A detailed family history is useful in diagnosing inflammatory arthritis. A patient with a first-degree relative who has rheumatoid arthritis has a two- to fourfold increased risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis.9

Clinical examination

Joint examination should be performed to look for features of synovitis, including joint tenderness to palpation, warmth, swelling and loss of motion. These findings are typical for an inflammatory arthritis. Clinical synovitis may be difficult to detect or absent in patients with early inflammatory arthritis. Referral should therefore be considered for patients with a history of joint pains with inflammatory features and positive autoantibodies or raised inflammatory markers.

Joint effusions can also occur in osteoarthritis, but they are generally small and cool. Joint examination should map the distribution of joint involvement, which can provide useful diagnostic information. For example, distal interphalangeal involvement is typical of osteoarthritis and psoriatic arthritis but not rheumatoid arthritis. The finding of joint deformities can also be diagnostic, such as squaring of the base of the thumb in osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint, or hand deformities that are typical of rheumatoid arthritis.

A skin and general examination should be performed to look for extra-articular manifestations, such as skin rashes, rheumatoid nodules and tophi.

Types of arthritis by distribution of joint involvement

Monoarthritis

Monoarthritis refers to arthritis that occurs in a single joint. Types of monoarthritis, their features and appropriate investigations are listed in Table 1.

Septic arthritis caused by bacterial infection occurs more frequently in large joints (shoulders, hips and knees) due to abundant blood supply. Although septic arthritis most often presents as a monoarthritis, it can also present as an oligo- or polyarthritis.

Calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate deposition (CPPD) and gout are forms of crystal arthritis that usually present as a monoarthritis. CPPD can be secondary to metabolic and endocrine disorders. Conditions including hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia, hypophosphataemia or genetic disorders such as haemochromatosis and haemophilia should be considered in recurrent cases of CPPD.10

Gout arises from elevated levels of serum uric acid. The presence of tophi is highly specific for gout and implies a level of chronicity. Oestrogen promotes excretion of uric acid in the urine, meaning gout is unlikely in premenopausal women.5 Gout in unusual situations should prompt evaluation for sinister causes of uric acid overproduction, such as myeloproliferative disorders and haemolysis.11

Gout is increasingly being recognised as a metabolic disease that is associated with poor cardiovascular prognosis when inadequately treated. Patients with gout should be appropriately screened and managed for modifiable cardiovascular risk factors (e.g. dyslipidaemia and diabetes).12

There are well-recognised uric acid treatment targets in established gout:

- less than 0.36 mmol/L for non-tophaceous disease

- less than 0.30 mmol/L for tophaceous disease.

Trauma-related injuries (e.g. hemarthrosis), ruptured Baker’s cysts and, rarely, neoplasms can also result in monoarthritis.

Oligoarthritis

Oligoarthritis refers to arthritis that involves two to four joints. Types of oligoarthritis, their features and appropriate investigations are listed in Table 2.

Osteoarthritis is traditionally an oligoarthritis that lacks inflammatory features. Osteoarthritis can affect any joint but often affects the hands, cervical and lumbar spine, hips and knees. Although stiffness is not traditionally considered to be a hallmark of osteoarthritis, it is increasingly recognised that patients with osteoarthritis do experience some degree of stiffness, particularly early in the disease course.13

Seronegative arthritis, or spondyloarthritis, is a broad term that includes conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis and enteropathic arthritis. It is distinct from seronegative rheumatoid arthritis. Psoriatic arthritis can present with several different patterns, including an asymmetrical oligoarthritis affecting small or large joints, arthritis affecting the distal interphalangeal joints, or a symmetrical polyarthritis similar to rheumatoid arthritis. It can also affect the spine and cause sacroiliitis, enthesitis and dactylitis.

Polyarthritis

Polyarthritis refers to arthritis that involves five or more joints. Types of polyarthritis, their features and appropriate investigations are listed in Table 3.

Viral arthritis can present as an acute-onset polyarthritis, which can mimic the onset of an inflammatory arthritis. Viral arthritis is usually self-limiting and resolves within weeks. It should be suspected in patients with a recent-onset arthritis, particularly if they have other features of a viral infection, such as fever or rash. Patients should be questioned about sick contacts and recent travel to assess whether certain viral pathogens should be considered in further diagnostic testing, depending on epidemiology.

Role of the ‘autoimmune screen’

Immunological tests can be helpful in the diagnosis of arthritis. However, there are many types of immunological tests, and only those that are relevant to the clinical presentation should be selected. The results should then be interpreted in the context of the clinical findings.

For arthritis, inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) and basic appropriate imaging are indicated, with further targeted immunological testing appropriate in cases where a particular inflammatory diagnosis is suspected.

Rheumatoid arthritis can be seronegative, with up to 25% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis symptoms testing negative for both rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide.14 There are also other inflammatory arthritis types that are seronegative. Negative rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide findings should not exclude further workup and evaluation for inflammatory arthritis. Patients with clear inflammatory joint symptoms, particularly if they have clinical synovitis or elevated inflammatory markers, should still be referred to a rheumatologist for assessment and consideration of further therapies. There is evidence to suggest that patients with seronegative inflammatory arthritis experience a delay to diagnosis and initiation of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.14

Similarly, antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing should be reserved for patients who have connective tissue disease-associated symptoms. These may include recurrent aphthous ulcers, significant alopecia, Raynaud’s phenomenon or photosensitive rash. ANA testing in the absence of compatible symptoms is discouraged, as up to 15% of the population have ANA positivity without an established autoimmune disease.15

Repeating serological tests that previously gave negative results should be avoided unless there is change in the patient’s clinical presentation. Research into the role of repeat ANA and extractable nuclear antigen testing after initial negative results has shown low clinical utility and high healthcare costs.16,17

Joint aspiration

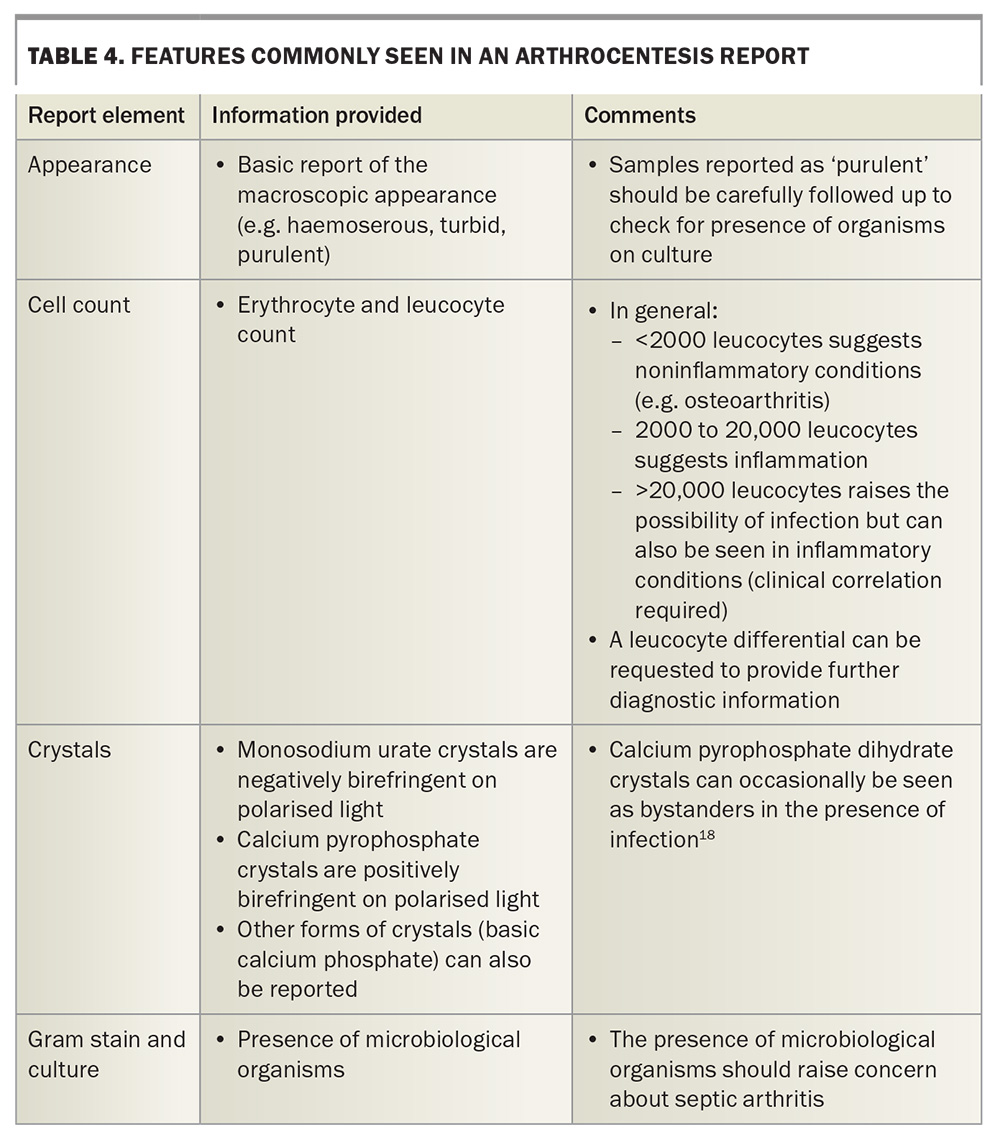

Arthrocentesis, or joint aspiration, plays an important part in assessment of joint conditions. Aspiration can be performed clinically by the bedside or requested via radiological assistance. Joint aspiration provides information including cell counts, crystal analysis using polarised light, Gram stain and culture (Table 4).18 The presence of organisms on Gram stain or culture should always raise concern about septic arthritis.

Arthrocentesis should be considered in the diagnostic workup of a joint effusion. Occasionally, joint aspiration can serve a therapeutic role in reducing intra-articular pressure. In cases of established arthritis with known joint disease, joint injections with corticosteroid may also be appropriate for targeted management.

Joint aspiration should be avoided where there is overlying cellulitis or broken skin because of the risk of introducing infection. Therapeutic anticoagulation is a relative contraindication, and joint aspiration is best done when a patient’s anticoagulation status is within therapeutic range (if measurement is possible). Joint aspiration and corticosteroid injections should not be performed in a known prosthetic joint without orthopaedic consultation, and they should be reconsidered in patients with systemic infection or other contraindications to systemic steroids, as there is a risk of systemic absorption.19

Imaging

Many forms of imaging can be requested to evaluate and monitor patients with arthritis. Although imaging has a role, it should only be used to supplement clinical assessment when necessary. In inflammatory arthritis, imaging can show joint erosions and damage with diagnostic patterns. Common radiological features for various forms of arthritis are listed in Tables 1 to 3. However, joint erosions and damage may not be evident on imaging early in the disease process, so their absence should not be used to rule out an inflammatory arthritis diagnosis.

In primary care, x-rays and ultrasounds are often the most easily accessible forms of imaging. These two modalities can detect erosions or structural anomalies, such as osteophytes and tophi. Synovitis can be detected on ultrasound with power Doppler. MRI is another imaging modality that can be used to interrogate disease activity and provide important information about joints and surrounding soft tissue. Although it has good sensitivity, MRI can be cost prohibitive, and MRI requests may attract a steep out-of-pocket cost.

Given there is evidence to suggest that musculoskeletal ultrasound and MRI are comparable when it comes to the evaluation of inflammatory arthritis, it is reasonable for GPs to request x-rays and ultrasound as their main imaging modalities for assessment of arthritis.20 Shared-care decision making between patients, GPs and other specialist providers may be beneficial before requesting MRIs.

When to refer

Local practice guidelines suggest that referral to a rheumatologist is recommended for patients with multiple swollen joints (particularly those with rheumatoid factor or anticyclic citrullinated peptide positivity) or for patients who have arthralgias requiring NSAID use for more than six weeks after initial treatment.21

Early referral and introduction of treatment for inflammatory arthritis is crucial for good patient outcomes. However, patients often experience a delay to first contact with a rheumatologist due to factors such as resource limitations and the heterogeneous and nonspecific symptoms that can be seen in early inflammatory arthritis.22

Some patients may require multiple reviews before inflammatory arthritis is recognised, but research into the experiences of patients with early arthritis suggests that a significant proportion experience severe pain that interferes with activities of daily living as an initial presenting symptom.23 Fatigue, swelling and stiffness are other important initial symptoms reported by patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Squeeze tenderness across the metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal joints has been shown to be a reliable screening tool for inflammatory arthritis that should prompt referral.

The presence of these symptoms or signs should prompt appropriate testing and consideration of early referral to a rheumatologist. For patients with clinical evidence of inflammatory arthritis, referral should not be delayed to await test results and should proceed even if the rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide test results are negative.

Treatment

The treatment of an underlying arthritis depends on the diagnosis. The specifics of arthritis treatment are not covered here, but prompt diagnosis and initiation of appropriate treatment will notably improve patient outcomes. This increases the likelihood of patients returning to their premorbid level of function and avoiding long-term structural damage.

Collaborative care with other specialists is often needed for patients with chronic arthritis. The GP plays a crucial role in supporting medication adherence (e.g. achieving treatment targets with uric acid-lowering therapy for gout) and working with specialists to facilitate appropriate monitoring for medication side effects.24-26

Additionally, as reflected in arthritis management guidelines, access to allied healthcare to improve mobility and function is crucial in arthritis treatment.27 A referral for a Team Care Arrangement through primary care helps patients achieve better access to appropriate services.

Collaborative care to encourage smoking cessation is associated with better clinical outcomes for patients with inflammatory arthritis and improved efficacy of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs.28,29

It is important to note that use of opioids for arthritis-related pain (especially chronic pain) is not supported by the literature.30,31 Given the inherent problems with opioids and their side effects, effective opioid stewardship should include deprescription for inappropriate indications and, in the case of persistent arthritis, escalation and discussion with specialists about treatment optimisation.

GPs often encounter and manage undifferentiated polyarthritis in their patients, and symptoms may require treatment while awaiting a diagnosis. NSAIDs are commonly used for treating pain, swelling and stiffness associated with inflammatory arthritis. Care should be taken when using NSAIDs in older patients or those with established renal disease. Paracetamol can be used in combination with, or instead of, NSAIDs for pain relief.

Prednisolone can be used, albeit sparingly and for a limited time, for patients with severe symptoms and functional impairment. Doses of prednisolone should generally not exceed 15 mg daily, and persistent symptoms should prompt contact with a rheumatology team for expedited review.4

Reliable information sources such as Therapeutic Guidelines can be helpful to guide practice with relevant medication information.4

Conclusion

Although there are many forms of arthritis, the presence of findings suggestive of inflammatory arthritis or red flags for septic arthritis should prompt early escalation of care.

Early and effective treatment enables best clinical outcomes for patients: it can improve their quality of life and overall health and decrease societal burden by reducing absenteeism and presenteeism. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Sutu received an honorarium from the limbic to speak at the 2024 Corridor Consult online seminar and support (course fees) from Janssen to attend the BJC Health Functional Movement workshop. Dr Ciciriello is Chair of the Australian Rheumatology Association Trainee Selection Committee.

References

1. Chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2023. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/musculoskeletal-conditions/contents/arthritis (accessed May 2024).

2. Fast facts. Sydney: Arthritis Australia; 2022. Available online at: https://arthritisaustralia.com.au/what-is-arthritis/fastfacts (accessed May 2024).

3. Schofield D, Cunich M, Shrestha RN, et al. The long-term economic impacts of arthritis through lost productive life years: results from an Australian microsimulation model. BMC Public Health 2018; 18: 654.

4. Rheumatology. In: Therapeutic Guidelines. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2017. Available online at: https://www.tg.org.au/ (accessed April 2024).

5. Robinson PC. Gout – an update of aetiology, genetics, co-morbidities and management. Maturitas 2018; 118: 67-73.

6. Hannu T. Reactive arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011; 25: 347-357.

7. Marks M, Marks JL. Viral arthritis. Clin Med (Lond) 2016; 16: 129-134.

8. Gisondi P, Bellinato F, Maurelli M, et al. Reducing the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl) 2022; 12: 213-220.

9. Frisell T, Saevarsdottir S, Askling J. Family history of rheumatoid arthritis: an old concept with new developments. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2016; 12: 335-343.

10. Iqbal SM, Qadir S, Aslam HM, Qadir MA. Updated treatment for calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease: an insight. Cureus 2019; 11: e3840.

11. George C, Leslie SW, Minter DA. Hyperuricaemia. In: StatPearls. Updated 11 February 2023. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459218 (accessed May 2024).

12. Cox P, Gupta S, Zhao SS, Hughes DM. The incidence and prevalence of cardiovascular diseases in gout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int 2021; 41: 1209-1219.

13. Berenbaum F. Osteoarthritis as an inflammatory disease (osteoarthritis is not osteoarthrosis!). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013; 21: 16-21.

14. Coffey CM, Crowson CS, Myasoedova E, Matteson EL, Davis JM III. Evidence of diagnostic and treatment delay in seronegative rheumatoid arthritis: missing the window of opportunity. Mayo Clin Proc 2019; 94: 2241-2248.

15. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA). Atlanta: American College of Rheumatology; 2023. Available online at: https://rheumatology.org/patients/antinuclear-antibodies-ana (accessed May 2024).

16. Yeo AL, Le S, Ong J, et al. Utility of repeated antinuclear antibody tests: a retrospective database study. Lancet Rheumatol 2020; 2: e412-e417.

17. Yeo AL, Leech M, Ojaimi S, Morand E. Utility of repeat extractable nuclear antigen antibody testing: a retrospective audit. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2023; 62: 1248-1253.

18. Rosales-Alexander JL, Balsalobre Aznar J, Magro-Checa C. Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease: diagnosis and treatment. Open Access Rheumatol 2014; 6: 39-47.

19. Courtney P, Doherty M. Joint aspiration and injection and synovial fluid analysis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2009; 23: 161-192.

20. Ranganath VK, Hammer HB, McQueen FM. Contemporary imaging of rheumatoid arthritis: clinical role of ultrasound and MRI. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2020; 34: 101593.

21. Early diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis. Melbourne: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2010. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/FSDEDEV/media/documents/Clinical%20

Resources/Guidelines/Joint%20replacement/Algorithm-for-the-diagnosis-and-management-of-early-rheumatoid-arthritis.pdf (accessed May 2024).

22. Warburton L, Hider SL, Mallen CD, Scott IC. Suspected very early inflammatory rheumatic diseases in primary care. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019; 33: 101419.

23. De Cock D, Van der Elst K, Stouten V, et al. The perspective of patients with early rheumatoid arthritis on the journey from symptom onset until referral to a rheumatologist. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2019; 3: rkz035.

24. Callear J, Blakey G, Callear A, Sloan L. Gout in primary care: can we improve patient outcomes? BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2017; 6: u210130.w4918.

25. Lawrence A, Scott S, Saparelli F, et al. Facilitating equitable prevention and management of gout for Maori in Northland, New Zealand, through a collaborative primary care approach. J Prim Health Care 2019; 11: 117-127.

26. Spencer NJ, Fryer AA, Farmer AD, Duff CJ. Blood test monitoring of immunomodulatory therapy in inflammatory disease. BMJ 2021; 372: n159.

27. England BR, Smith BJ, Baker NA, et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology guideline for exercise, rehabilitation, diet, and additional integrative interventions for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2023; 75: 1603-1615.

28. Vittecoq O, Richard L, Banse C, Lequerré T. The impact of smoking on rheumatoid arthritis outcomes. Joint Bone Spine 2018; 85: 135-138.

29. Tillett W, Jadon D, Shaddick G, et al. Smoking and delay to diagnosis are associated with poorer functional outcome in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 1358-1361.

30. Moore MN, Wallace BI. Glucocorticoid and opioid use in rheumatoid arthritis management. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2021; 33: 277-283.

31. Jones CMP, Day RO, Koes BW, et al. Opioid analgesia for acute low back pain and neck pain (the OPAL trial): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2023; 402: 304-312.