Immunisation against tuberculosis for children travelling overseas

The bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccine prevents tuberculosis (TB) meningitis and disseminated TB in young children. GPs are encouraged to recommend this vaccine to at-risk young children visiting families and relatives in countries with a high TB incidence.

- Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading infectious disease-associated cause of death globally.

- Families originating from countries with a high TB burden frequently travel with their young children back to their country of origin to visit families and relatives (VFR).

- The bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine protects these VFR children against serious TB diseases.

- The BCG vaccine should be offered to these children, but access to the vaccine is limited in Australia.

- Strong expertise is required to deliver BCG immunisation without adverse events; however, there is a lack of well-trained medical personnel.

- A resolute national solution is critically needed to prevent further cases of paediatric TB associated with overseas travel.

Children who travel overseas from Australia to countries with a high tuberculosis (TB) incidence, primarily visiting families and relatives (VFR), are at risk of contracting TB. The bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine is the most effective means of preventing TB meningitis (TBM) and disseminated TB in young children. BCG immunisation is available in specialist clinics in Australia. GPs are encouraged to recommend this vaccine to at-risk young VFR children.

Per the Global Tuberculosis Report 2024 by the World Health Organization (WHO), about 8.2 million people were reported with newly diagnosed TB in 2023.1 This was the highest number recorded since the WHO commenced global TB monitoring in 1995 and an increase from 7.5 million people reported in 2022. TB has again become the leading infectious disease cause of fatality, replacing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1

According to Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General: ‘The fact that TB still kills and sickens so many people is an outrage, when we have the tools to prevent it, detect it and treat it. WHO urges all countries to make good on the concrete commitments they have made to expand the use of those tools, and to end TB.’2

Global milestones and targets for reductions in TB disease burden have been off-track. Substantial resources were diverted away from TB and other public health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Low- and middle-income countries faced significant funding shortages, accounting for 99% of the reported number of people with newly diagnosed TB each year.1 This article provides an overview of BCG immunisation against TB in Australia for VFR children.

Bacille Calmette–Guérin vaccine

The BCG vaccine was developed between 1908 and 1921 by two French scientists who worked at the Pasteur Institute: Albert Calmette (1863–1933) and Camille Guérin (1872–1961). It is a live-attenuated vaccine derived from Mycobacterium bovis that was originally isolated in 1902 from a tuberculous cow. The BCG vaccine is among the oldest vaccines, and currently the only available TB vaccine. Several BCG vaccines based on different BCG strains are used worldwide.3

The BCG vaccine is the most effective at preventing severe TB (miliary TB and TBM) in children.3,4 BCG immunisation has been estimated to be about 70% effective at preventing TBM and 80% effective against miliary infection in children aged younger than 5 years when given during infancy in endemic settings. It also confers close to 70% protection against active TB and 25% protection against TB infection.4-6 Without treatment, about 5% of people infected with TB bacteria develop TB disease in the first two years after infection, and another 5% sometime later in life.7

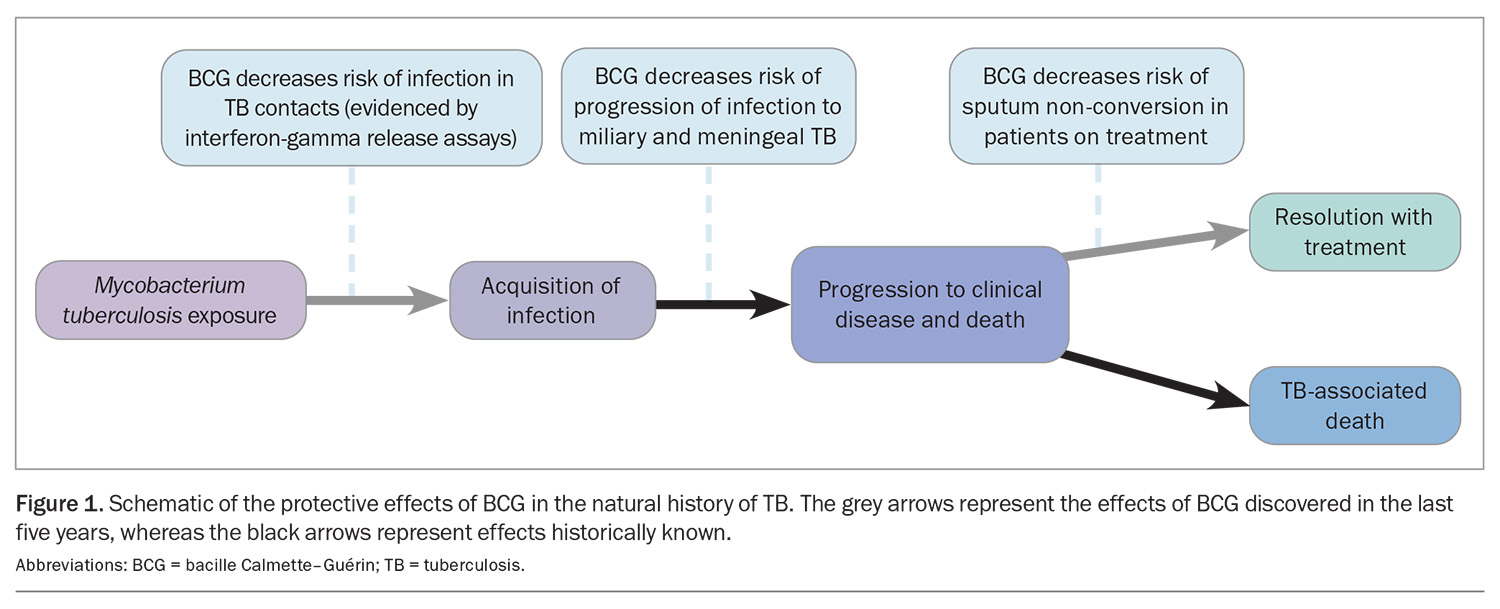

In recent years, the interferon-gamma release assay was utilised in studies comparing the acquisition of TB infection in BCG- and non-BCG-vaccinated infants. The results indicated that the BCG vaccine prevents infection in addition to progression

(Figure 1).8

Global epidemiology of tuberculosis

People who had TB in 2023 mainly resided in the WHO regions of South-East Asia (45%), Africa (24%) and the Western Pacific (17%).1 The most popular destinations for migrant Australian VFR travellers were located in these areas (further details can be found in the Global Tuberculosis Report: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024).1

Paediatric TB infection in countries with a low TB incidence mainly affects children born in migrant families.9,10 The risk of acquiring TB in children VFR during travel in regions with a high TB incidence may be as high, or even higher than that in the native population.9

Children aged younger than 5 years carry a higher risk of developing active TB after primary infection, particularly if aged younger than 2 years.11-14 Their risk of progression to active disease, including severe disseminated disease, is substantial.15 In the pre-chemotherapy era, young TB-exposed children not given the BCG vaccine were noted to have a 20% risk of miliary TB and TBM without TB preventive therapy.13,16,17 The presentations of TBM are typically nonspecific in children. The diagnosis is often made late, if at all. Despite treatment, the mortality rate is 20% among children with TBM, and among those who survive, most are left with neurological disability.16,18 In addition, TB-infected children who do not develop active disease and are not given TB preventive therapy constitute a reservoir of TB in the communities.19,20

Epidemiology of tuberculosis in Australia

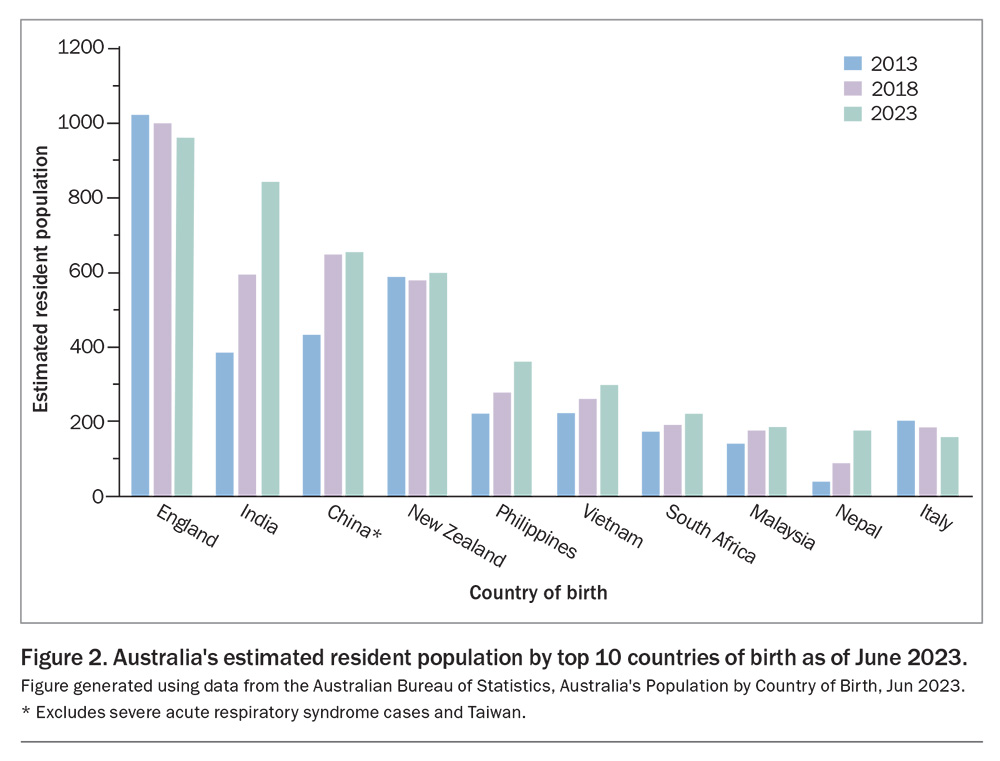

The risk of TB in Australia is low. The incidence remains less than seven per 100,000 population annually since the 1980s. More than 85% of TB cases in Australia occur in people who were born overseas, mainly in countries with a high burden of TB. Notifications of TB among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Far North Queensland and the Northern Territory are disproportionately higher than for those in other states.4 A large proportion of immigrants to Australia came from countries with a high TB prevalence (Figure 2).21 They regularly travel to their home countries with their young children as VFR travellers. The countries of birth (excluding Australia) with the largest increases in Australia’s population between 2013 and 2023 were:

- India: increase of 467,000 people

- China: increase of 223,000 people

- Nepal: increase of 144,000 people

- the Philippines: increase of 143,000 people.

National guidelines on BCG immunisation

In Australia, the BCG vaccine is recommended for children aged younger than 5 years travelling to countries with a high TB incidence (>40 cases per 100,000 population per year), as well as children aged younger than 5 years residing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia with a high incidence of TB.4 In 2022, two changes were made in the recommendation for BCG immunisation in the Australian Immunisation Handbook:

- a minimum length of travel per trip is no longer a prerequisite indication, but instead, is a part of the overall risk assessment. Migrant families often visit their country of origin once every one to two years, and the cumulative duration should also be considered. On the other hand, a strong probability of close contact with TB while overseas is an indication for BCG vaccination, even for one short VFR trip

- a routine tuberculin skin test (TST) or Mantoux test for screening before vaccination is only required in some circumstances, based on an individual risk assessment. A TST prior to BCG vaccination should be performed if the child was born in a TB-endemic country (>40 cases per 100,000 population per year), has lived or travelled to a TB-endemic region or has had close contact with TB.4

Except in certain healthcare workers (HCWs), BCG vaccination is not recommended for older children and adults. The evidence of the benefit of BCG vaccination is limited in these individuals. Consider BCG vaccination in HCWs with negative TST results, working in settings with a high TB incidence, particularly those with limited infection prevention and control measures, and who are very likely to be exposed to drug-resistant TB, which is difficult to treat.4

The BCG vaccine can offer protection against Mycobacterium leprae, which causes leprosy.4,22 BCG may offer some protection against Buruli ulcer and other nontuberculous mycobacterial infections.3 Using a different preparation that is directly instilled into the bladder, BCG has been shown to be effective in treating superficial bladder cancer since the 1970s.4

Duration of protection and revaccination

In some populations, protection after primary infant BCG vaccination could persist for as long as 15 years, although it declines with time. A long-term follow-up study in northern North America including adults who had been vaccinated neonatally with BCG showed protection against all TB outcomes 50 to 60 years later.23 Data from a retrospective study in Norway also revealed evidence of a long duration of protection that waned after 20 years.3

Revaccination is not recommended.3,23 There is minimal to no evidence of any additional benefit of repeat BCG vaccination against TB or leprosy. There is also no evidence that BCG vaccination is effective when used for postexposure prophylaxis.3

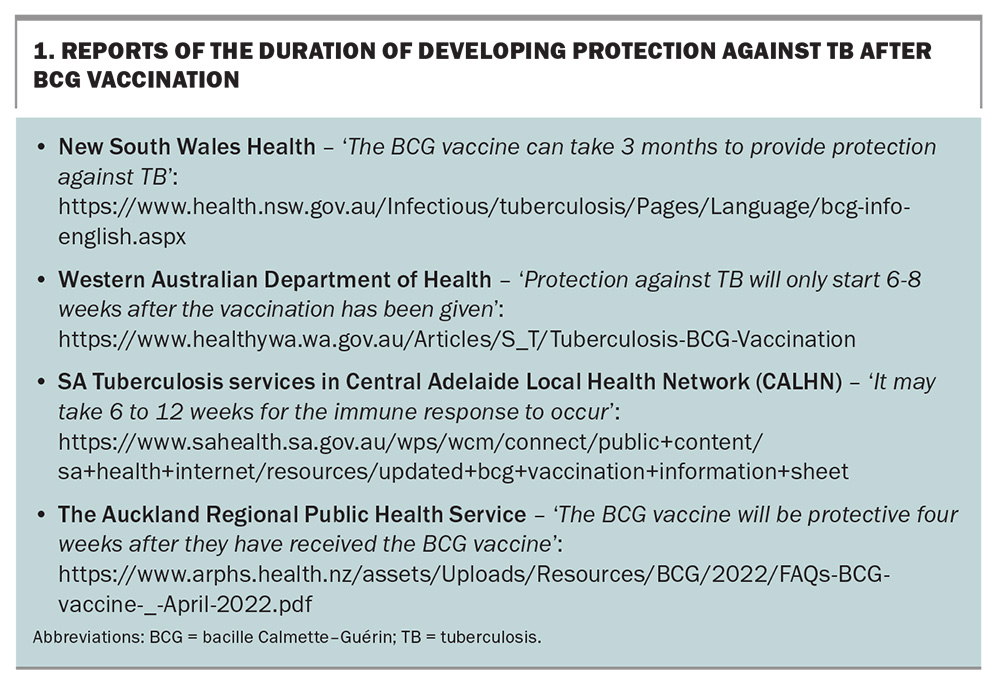

The views differ regarding the time it takes to develop protection against TB after BCG vaccination, warranting published data. Box 1 lists some resources with varying reports of the duration of developing protection.

BCG immunisation in Australia

The only BCG vaccine (Sanofi-Aventis Australia) registered for use in Australia has not been available since 2012.4 As a replacement, the TGA has approved the use of BCG Vaccine AJV powder for injection, lyophilised – Mycobacterium bovis Danish strain 1331 with Diluted Sauton AJV (New Zealand), under Section 19A provisions of the TGA Act (approval holder: Link Medical Products Pty Ltd).24 The minimum order is 10 vials. After reconstitution, each vial makes up 1 mL of the vaccine. The recommended dose is 0.1 mL intradermal (ID) for children aged older than 1 year or 0.05 mL ID for those aged younger than 1 year. The shelf life of the vials is up to one year.

BCG vaccination is provided in both public and private clinics, mainly in major cities in Australia. Public clinics provide the service at no cost to Australian residents holding Medicare cards. A GP referral is mandatory. The waiting time for BCG vaccine appointments at public clinics nationwide is quite variable. BCG vaccination is accessible through Australian Capital Territory Health at the Canberra Hospital for children aged younger than 5 years with an average wait time of four months. The waiting period is comparable in Queensland and South Australia. In contrast, parents can book appointments at the TB Clinics at the Royal Darwin Hospital and the Alice Springs Community Centre within a few weeks. In Victoria, publicly funded BCG vaccination is only available at the Royal Children’s Hospital (RCH) and the Monash Medical Centre (MMC). Both the MMC and RCH run an outpatient BCG clinic once a week. The RCH only offers the vaccine to infants aged younger than 12 months. The waiting time is more than six months at both institutions. West of Melbourne, the University Geelong Hospital (part of Barwon Health) no longer renders the service, as they do not have a BCG vaccinator. Many migrant families with Indian subcontinent origin (a region with high TB incidence) reside in the western metropolitan region in Victoria. In other states and territories, publicly funded BCG vaccination is obtainable via the respective public health TB services.

The Melbourne Vaccination Education Centre (MVEC) publishes a list of private BCG clinics in Victoria on its website (https://mvec.mcri.edu.au/references/tuberculosis-bcg/). This website was recently relaunched following a public petition, after the MVEC suspended their services in mid-2024 because of a lack of funding.

Appointments for BCG vaccination can readily be made at private clinics. However, the out-of-pocket cost can be a deterrent, comprising the consultation fees (partly Medicare reimbursable) and the cost of the vaccine (which is not Medicare claimable and does not contribute to the PBS safety net).

The BCG vaccine is ideally administered at least three months prior to departure to a high-risk destination.4 Parents, however, seldom plan so far ahead. We have occasionally given the BCG vaccine to young children as close as one day before their overseas travel. Although giving the BCG vaccine belatedly may not induce protection for the imminent VFR trip, it is still worthwhile for a long stay, and certainly for VFR trips in subsequent years.

As prerequisites for delivering BCG immunisation effectively and safely, nursing and medical services providers must be proficient in:

- vaccinating young children

- administering ID vaccinations

- providing education and counselling to parents regarding the progression and management of the BCG vaccination site.

The providers must be conversant and up to date with the recommendation in the Australian Immunisation Handbook, as well as capable of managing any postvaccination adverse reactions.4

Administering the BCG vaccine

The BCG vaccine can be given at any time in relation to other inactivated vaccines or oral live vaccines. Other parenteral live vaccines should be given at least one month apart from the BCG vaccine (e.g. measles, mumps and rubella at 12 months of age and measles, mumps, rubella and varicella at 18 months of age). Live vaccines may otherwise be given on the same day if the child is departing Australia very soon. The BCG vaccine is conventionally given on the upper left arm. It facilitates the future recognition of evidence of BCG vaccination.4 Vaccinating on the upper thigh is no longer practised. A post-BCG vaccination TST to demonstrate immunity is not recommended.4 No other vaccine should be administered into the same (left) arm for three months following BCG vaccination, because of the risk of regional lymphadentitis.4,25 Detailed instructions for TST and BCG vaccination with graphic demonstration are available online (Box 2).

Overall, the BCG vaccine is effective and safe.3,4 Details on contraindications and precautions can be found in the Australian Immunisation Handbook.4 A reaction develops at the injection site in about 95% of BCG vaccine recipients, usually within two to three weeks. It spontaneously heals in two to five months (often in three months), leaving a small permanent palpable superficial scar.3 Without complications, the healing process is painless. Administered intradermally, fewer than 5% of vaccinated individuals experience adverse events: about 2.5% may develop a cold abscess at the injection site, and about 1% may develop regional lymphadenitis with or without cold abscess formation.4,25 The absence of a BCG scar after vaccination is not indicative of a lack of protection and is not an indication for revaccination.3

Other adverse events are less common.3,4 The risk of hypertrophic scar or keloid formation may be minimised by injecting the BCG vaccine no higher than the region where the deltoid muscle inserts into the humerus. The risk of disseminated BCG disease is very low (one to four cases per one million vaccinated people). It is only observed in immunocompromised recipients. If the recipient’s carers or close contacts are immunosuppressed, BCG vaccination is relatively contraindicated.

A pre-BCG TST is required if indicated. Those with latent or past TB infection are likely to have an accelerated cutaneous response after receiving the BCG vaccine, although the response is not substantially more severe than a typical BCG reaction and is without any long-term detrimental effect. The response is characterised by:

- induration within one to two days

- pustule formation within one week

- healing within two weeks.4

For optimal BCG vaccination, the injecting needle must remain in situ superficially under the skin on the child’s (left) arm for a few seconds. Vaccinating a large, wriggling child is particularly challenging. Movement of the child can result in the vaccine being given subcutaneously rather than intradermally, and at times, double puncturing. Inadvertent subcutaneous injection of the BCG vaccine typically gives rise to the formation of a large cold abscess that heals belatedly (frequently, taking a lot longer than three months). The RCH in Melbourne has ceased providing BCG vaccination to children aged older than 1 year. Queensland Health offers the service only to children aged up to 3 years (per personal communication). Mastery of BCG vaccination averts adverse reactions. At the Melbourne Travel Doctor – The Traveller’s Medical & Vaccination Centre Clinic, BCG vaccination has been provided since the early 1990s, primarily for VFR children aged 5 years and younger. Between September 2021 and December 2024, 582 doses of the BCG vaccine were administered by one nursing staff member (with a few exceptions), who is the most experienced BCG vaccinator on the team (Box 3). No adverse events were recorded throughout this period. From 2013 to 2020, the BCG vaccinating duty was shared among the nursing team. Thirteen cases of delayed healing occurred (in addition to one case in an adult: a HCW relocating to work in the United Kingdom). Secondary vaccination site infection or other adverse events did not eventuate.

The families could not attend the clinic regularly because of practicalities. The author corresponded with the parents of each of the 13 children via weekly to monthly emails (and directly with the additional affected adult), monitoring the progress by means of successive photographs of the vaccination sites, while supporting the parents. All 14 individuals showed spontaneous healing without requiring anti-TB medications or surgical intervention. The longest time of resolution was about one year; the size of the BCG scars in this individual was appreciably larger than the scars in the uncomplicated cases. The scars progressively reduced in size.

BCG vaccination before planning overseas trips

Both parents should attend the BCG vaccination session with their child. It is beneficial for both parents to listen to the briefing by the healthcare team and be well informed about the process. The author always asks the parents to consult local medical practitioners experienced in BCG vaccinations if adverse reactions occur when overseas. Otherwise, under the circumstances, HCWs without such expertise tend to offer unhelpful and improper feedback that complicates the management and intensifies the anguish of the parents. A medicolegal case example is presented in Box 4.26,27

Many parents self-refer their young children to private clinics for BCG vaccination as they plan their overseas VFR trips. They are either aware that the BCG vaccine is given routinely to newborn infants in countries of their origin or are advised accordingly by their GPs or maternal childcare nurses. Nonetheless, this cohort is unlikely to constitute a sizeable proportion of the VFR population. More efforts from all stakeholders to raise awareness are rewarding, targeting the HCWs among communities of migrant and refugee families and proactively advocating BCG vaccination for their children, ideally before reaching 1 year of age, and well before their first overseas VFR journey.

At present, the average waiting time for publicly funded BCG immunisation in Australia is too long. One main contributing factor is an insufficient number of well-trained BCG vaccinators. In Victoria, the pool of BCG vaccinators dwindles through natural attrition. NSW Health has established a supervised training and competency assessment.28 It takes as long as 12 to 18 months to train a registered nurse to become an accredited independent BCG vaccinator.29 The Australian College of Nursing offers a 10-week online TB management course for registered nurses, known as 357 Tuberculosis Management (TST/BCG) (https://www.acn.edu.au/education/non-award/tuberculosis-management). However, the course teaches the theoretical framework without a practical component. Private clinics do not have the capacity to run accredited training courses independently. Moreover, fee-paying parents are not inclined to participate. The following endeavours would facilitate and sustain better access to BCG vaccination for VFR children in Australia in the long term:

- standardisation of BCG vaccination programs across jurisdictions nationwide

- establishment of structured BCG vaccinator training courses leading to national accreditation. In contrast to the online yellow fever vaccination course, an integral clinical and practical curriculum is crucial. Collaboration with private clinics broadens this capacity.

Perhaps in association with the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance, the interim Australian Centre for Disease Control can play a co-ordinating role.

Conclusion

According to the 2021 Australian Census, almost half (48.2%) of Australians have an overseas-born parent, with many originating from developing countries that are endemic to TB.30 They regularly travel back to their country of origin together with their young children, who are potentially exposed to TB. The demand for BCG vaccines is increasing in Australia. The BCG vaccine is safe and effective in preventing severe TB and perhaps even TB infection in these children.

Currently, there is a significant deficiency in delivering TB immunisation in Australia. Adequate funding and public health initiatives to improve access to BCG immunisation are essential to minimise the risk of TB infection and diseases, mitigate the disease’s impact and improve outcomes for those at risk. The benefits are long-lasting. Commitments from governments and health services to prevent further cases of paediatric TB associated with overseas travel are worthwhile and cost-effective. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Lau works at the Sonic HealthPlus Travel Doctor – TMVC, administering BCG vaccines at the Melbourne and Canberra clinics.

References

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Tuberculosis Report 2024. Geneva: WHO; 2024. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024 (accessed February 2025).

2. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO News Release. Tuberculosis resurges as top infectious disease killer. Geneva: WHO; 2024. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-10-2024-tuberculosis-resurges-as-top-infectious-disease-killer (accessed February 2025).

3. World Health Organization (WHO). BCG vaccines: WHO position paper, February 2018, Weekly epidemiological record, No. 8, 93; 2018, p. 73-96. Geneva: WHO; 2018. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9308-73-96 (accessed February 2025).

4. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). Australian Immunisation Handbook. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2022. Available online at: https://www.immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au (accessed February 2025)

5. Smith B, Hazelton B, Heywood A, et al. Disseminated tuberculosis and tuberculous meningitis in Australian-born children; case reports and review of current epidemiology and management. J Paediatr Child Health 2012; 49: E246-E250.

6. Bourdin Trunz B, Fine P, Dye C. Effect of BCG vaccination on childhood tuberculous meningitis and miliary tuberculosis worldwide: a meta-analysis and assessment of cost-effectiveness. Lancet 2006; 367: 1173-1180.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Clinical Overview of Tuberculosis Disease (31 Jan 2025). Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2025. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/hcp/clinical-overview/tuberculosis-disease.html (accessed February 2025).

8. Lalvani A, Sridhar S. BCG vaccination: 90 years on and still so much to learn. Thorax 2010; 65: 1036-1038.

9. Perrez-Porcuna TM, Noguera-Julian A, Riera-Bosch MT, et al. Tuberculosis among children visiting friends & relatives. J Travel Med 2024; 31: taae037.

10. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, WHO Regional Office for Europe. Tuberculosis surveillance and monitoring in Europe 2021–2019 data. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2021. Available online at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/tuberculosis-surveillance-and-monitoring-europe-2021-2019-data (accessed February 2025).

11. Toms C, Stapledon R, Coulter C, Douglas P; National Tuberculosis Advisory Committee. Tuberculosis notifications in Australia, 2014. Communicable Diseases Intelligence 2017; 41: E247-E263.

12. Vanden Driessche K, Persson A, Marais BJ, et al. Immune vulnerability of infants to tuberculosis. Clin Dev Immunol 2013; 2013: 781320.

13. Marais BJ, Gie RP, Schaaf HS, et al. The natural history of childhood intra-thoracic tuberculosis: a critical review of literature from the pre-chemotherapy era. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004; 8: 392-402.

14. Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoSMed 2016; 13: e1002152.

15. Holmes RH, Sun S, Kazi S, et al. Management of tuberculosis infection in Victorian children: a retrospective clinical audit of factors affecting treatment completion. PLoS ONE 2002; 17: e0275789.

16. Du Preez K, Jenkins H, Donald P, et al. Tuberculous meningitis in children: a forgotten public health emergency. Front Neurol 2002; 13: 751133.

17. Martinez L, Cords O, Horsburgh CR, Andrews JR. Pediatric TBCSC. The risk of tuberculosis in children after close exposure: a systematic review and individual-participant meta-analysis. Lancet 2020; 395: 973-984.

18. Thwaites GE, Tran TH. Tuberculous meningitis: many questions, too few answers. Lancet Neurol 2005; 4: 160-170.

19. Soriano-Arandes A, Caylà JA, Gonçalves AQ, et al. Tuberculosis infection in children visiting friends and relatives in countries with high incidence of tuberculosis: a study protocol. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99: e22015.

20. Nelson LJ, Wells CD. Global epidemiology of childhood tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004; 8: 636-647.

21. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Australia’s Population by Country of Birth. Canberra: ABS; 2023. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/australias-population-country-birth/latest-release (accessed February 2025).

22. Zodpey SP, Bansod BS, Shrikhande SN, et al. Protective effect of Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) against leprosy: a population-based case-control study in Nagpur, India. Leprosy Review 1999; 70: 287-294.

23. World Health Organization (WHO). Report on BCG vaccine use for protection against mycobacterial infections including tuberculosis, leprosy, and other nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) infections. Geneva: WHO; 2017. Available online at: https://terrance.who.int/mediacentre/data/sage/SAGE_Docs_Ppt_Oct2017/11_session_BCG/Oct2019_session11_BCG_vaccine_use.pdf (accessed February 2025).

24. Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). BCG Vaccine AJV powder for injection, lyophilized - mycobacterium bovis (BCG) Danish strain 1331 with Diluted Sauton AJV (New Zealand). Canberra: TGA; 2025. Available online at: https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/section-19a-approvals/bcg-vaccine-ajv-powder-injection-lyophilized-mycobacterium-bovis-bcg-danish-strain-1331-diluted-sauton-ajv-new-zealand (accessed February 2025).

25. Turnbull FM, McIntyre PB, Achat HM, et al. National study of adverse reactions after vaccination with bacille Calmette-Guérin. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34: 447-453.

26. Sexena H. GP settles for $210k after paediatric patient contracts TB meningitis - The Sydney doctor told the child’s parents she didn’t need a BCG vaccination for their trip to Vietnam. AusDoc, 6minutes News; 2021. Available online at: https://www.ausdoc.com.au/news/gp-settles-210k-after-paediatric-patient-contracts-tb-meningitis/ (accessed February 2025).

27. New South Wales Caselaw. Supreme Court, New South Wales, Choi v Dr Ong [2021] NSWSC 178. Sydney: Supreme Court, New South Wales; 2021. Available online at: https://www.caselaw.nsw.gov.au/decision/177fad04b4233946693e86f8 (accessed February 2025).

28. NSW Health. TST BCG Competency Assessment. Sydney: NSW Health; 2024. Available online at: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/tuberculosis/Pages/tst-bcg-competency-assessment.aspx (accessed February 2025).

29. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). Australian Immunisation Handbook: Responses to Public Consultation Submissions. Changes to the recommended use of BCG vaccine to prevent tuberculosis. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care; 2022. Available online at: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-09/Summary-of-TB-Public-Consultation-Feedback-August-2022.pdf (accessed February 2025).

30. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2021 Census: Nearly half of Australians have a parent born overseas. Canberra: ABS; 2022. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/2021-census-nearly-half-australians-have-parent-born-overseas (accessed February 2025).