Jet lag – strategies to minimise effects

Jet lag is a potential consequence of overseas travel, with many travellers suffering from its symptoms, including sleepiness, insomnia and fatigue. Certain measures including light exposure and avoidance can be taken before, during and after the journey to mitigate these effects.

Following COVID-19 lockdowns and travel restrictions over the past few years, people in Australia are now able to resume international travel to their favourite destinations. For most, this represents a long overdue holiday with rest, relaxation and enjoyment. However, travel across time zones may bring forth an unfortunate consequence – jet lag. Affecting up to 70% of travellers,1 this circadian rhythm disorder can disrupt vacation plans with a constellation of undesired symptoms; however, strategies are available to minimise these effects.

What is jet lag?

Jet lag, also known as jet lag disorder, jet lag syndrome or time-zone change syndrome, is defined as a misalignment between the body’s own circadian rhythm and the new sleep-wake pattern in the new time zone.2 In essence, during jet lag our cycles of activity and rest that co-ordinate mental, physical and biological activity are conducted at a different time from usual. Although hormonal regulation, body temperature, eating and digestion may be affected, dysregulation of the sleep-wake cycle is most noticed by travellers.3

Our body clock

Our circadian rhythm is thought to have evolved to adapt to the light and dark of the solar cycle. In most people, the circadian clock tends to run slightly longer than 24 hours. This rhythm resets every day based on the environment’s light and darkness.

The primary circadian pacemaker in mammals is the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).4 This is a paired structure consisting of more than 20,000 neurons located in the anterior hypothalamus of the brain. The SCN synchronises the circadian clocks found in almost all peripheral cells, organs and the rest of the brain. Although the SCN can generate its own rhythm, it also receives direct light response from specialised melanopsin-containing photoreceptors in the retina enabling it to orchestrate, or otherwise align, to the day-night cycle. In the absence of light, the SCN cells are still able to remain synchronised with one another through coupling mechanisms.

Synchronising agents in the external environment that entrain the endogenous circadian rhythm include physical activity, temperature, social activities and, most importantly, light. These cues are known as zeitgebers, a German word for time giver or synchroniser.5 Light is the strongest zeitgeber, which can be manipulated to advance or delay the circadian rhythm. A phase delay results in a later bedtime and get-up time, whereas a phase advance results in an earlier bedtime and get-up time.

Melatonin

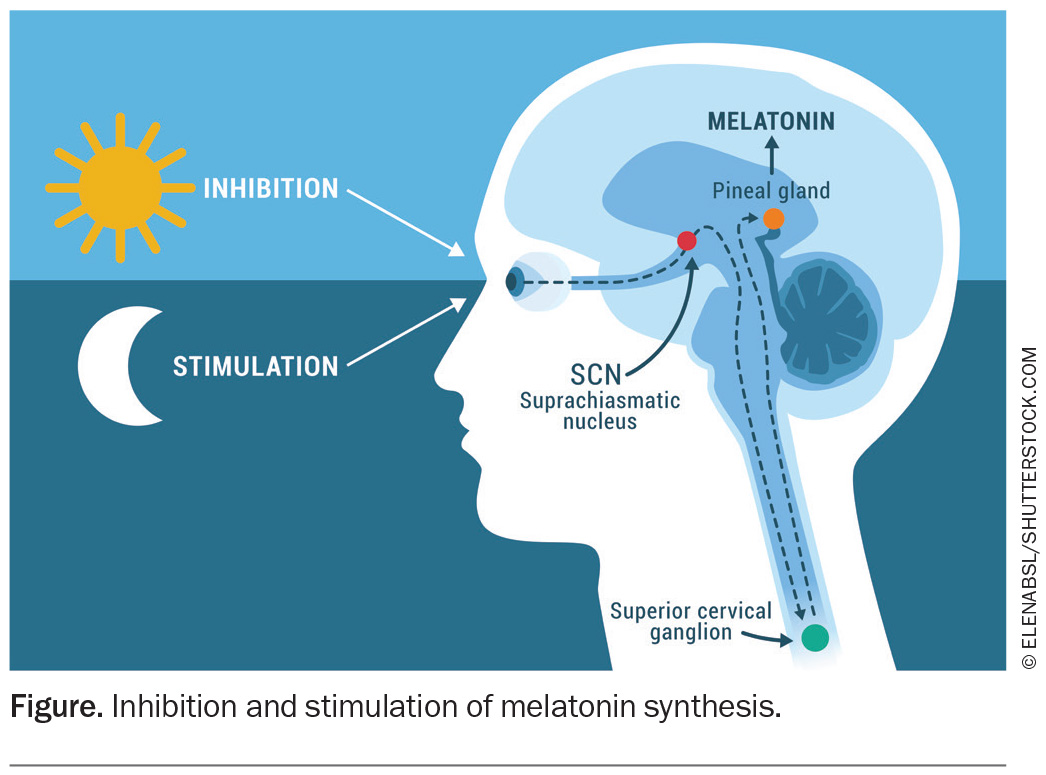

Melatonin, a neurohormone produced by the pineal gland, is a pivotal internal agent for the endogenous circadian rhythm. The SCN controls melatonin secretion via a complex multisynaptic pathway. Melatonin synthesis and release is stimulated by darkness. Its level rises after the onset of dusk, typically about two hours before sleep onset, peaks in the middle of sleep and progressively falls in the latter half of the night. The nadir of core body temperature (Tmin) occurs about two hours before habitual offset of sleep. Tmin is an important time, as any light exposure before this time will result in a phase delay, whereas any light after Tmin will induce a phase advance.

As shown in the Figure, production of melatonin is inhibited when the pineal gland receives signals from the SCN via the superior cervical ganglion in the presence of light, particularly blue light. Blue light (wavelength 460 nm) suppresses melatonin production for longer and to a larger degree than lights of other wavelengths (red or green). This knowledge has been used by manufacturers to promote blue light filters in electronic devices. Avoiding bright screens two to three hours before bed reduces the likelihood of any shift to the circadian rhythm.

Jet lag symptoms

Travel invariably alters the zeitgebers and, as a result, affects our sleep-wake cycle. At our holiday destination, in another time zone, we are exposed to a mismatched level of light intensity and duration and time to our own body clock. This can lead to excessive daytime sleepiness, as well as an inability to achieve a usual duration of sleep. Consequently, the traveller may suffer from fatigue and malaise, affecting their social or vocational commitments. Somatic symptoms such as nausea and diarrhoea are also common. These symptoms occur within one or two days of reaching the destination.

Although the classic definition of jet lag requires at least two time zones to be crossed, similar symptoms may be experienced after shorter travels, depending on the malleability of the traveller’s circadian rhythm to adapt to the time change. The earth rotates 360 degrees in a full day, and there are 24 time zones or regions around the world, each representing 15 degrees of longitude or one hour. The severity of an individual’s clinical symptoms relates to the direction of travel and the number of time zones crossed. It is usually easier to realign a circadian rhythm when travelling west (which requires delaying circadian rhythm and sleep-wake hours) than travelling east.

In addition, the international date line (IDL) divides the western and eastern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line, which is not absolutely straight, running from the North to South Pole. This marker defines the boundary between one day and the next. The IDL lies a few hours east of Australia. When travelling across the line to the west, a day is added. In contrast, when travelling east across the IDL, a day is subtracted. Therefore Kiritimati, Kiribati (GMT +14) would have the same time as Honolulu, Hawaii (GMT −10) and be a day apart.

After travelling east, in the new time zone the traveller is trying to sleep when the body’s biological clock is promoting alertness. The time to get up from bed is when the circadian clock is still encouraging sleep, leading to difficulty awakening.

After travelling west, in the evening hours of the new time zone, sleepiness and fatigue are felt as it is past the traveller’s bedtime. Moreover, early morning wakening is common as the body clock is promoting wakefulness when the traveller should be still sleeping.

The analogy here is that it is easier to stay up later watching a movie and wake up later the next day than going to sleep a few hours before the usual bedtime and waking up early for a meeting.

Common holiday destinations for travellers from Australia based on direction from the east coast, unless specified otherwise, are listed in the Box.

Symptoms of jet lag typically subside within a few days or up to a week.6 A general rule of thumb is that it takes one day to recover and acclimatise for each time zone travelled. This is not always the case and poses certain implications when travelling long distances. Consumption of alcohol, stress, inability to sleep on the flight, class of ticket and amount of zeitgebers present are factors that can worsen jet lag.

Role of the GP

It is uncommon for a patient to attend a GP consultation for the sole reason of managing jet lag, unless at a dedicated travel clinic. Travel immunisations or health advice may prompt a patient to see their GP or travel clinic a few weeks before travel.7 As phase shifting is most effective when started before the flight, this is an ideal time to provide patients with a pretravel plan (see ‘Management’ below). At this visit, a script for a sedative or melatonin may be sought (see later section, ‘Melatonin’).

Sleep disturbance should not precede or last months after travel. If it does, a concurrent sleep disorder, such as obstructive sleep apnoea, should be considered. Validated screening tools, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, Berlin Questionnaire, Wisconsin Sleep Questionnaire, STOP-BANG questionnaire, are recommended. A high score on these tests should prompt a referral to a sleep physician and diagnostic polysomnography/sleep study. Aside from the temporality with travel, symptoms of jet lag are nonspecific and may arise from other medical, neurological or mental health disorders, or medication or substance use.

Management

A key component to function or adapt in a new environment is achieving quality and consolidated sleep at a socially acceptable time. Hence, the goal for managing jet lag is to realign the endogenous circadian rhythm to the destination’s time zone.6

Circadian rhythm can be either advanced or delayed. About 75% of the population have an endogenous circadian rhythm of greater than 24 hours; in such individuals, inducing a phase delay is much easier to achieve. Tests to determine an individual’s circadian rhythm length are not routinely performed and are based on clinical and sleep history.

The cornerstones of therapy are:

- recognising the direction of travel

- starting phase shifting before travel

- using one of the most powerful and accessible tools – light.

Sleep hygiene

Good sleep habits can help improve sleep regardless of travel. Although certain behaviours, such as going to bed and waking up at the same time every day, will not apply when phase shifting, other practices remain pertinent, including the following:

- avoid caffeine (in the form of coffee, tea and soft drinks) and a large meal close to bedtime

- organise important work calls and meetings earlier in the day to prevent mental stimulation at night

- even on holiday, use the bed only for sleep and intimacy

- watching television, using the laptop and reading books are best done out of bed.

A comprehensive list of good sleep habits, including a printable copy, can be found on the Sleep Health Foundation website (https://www.sleephealthfoundation.org.au/sleep-topics/sleep-hygiene-good-sleep-habits).

In flight

It is important to wear comfortable clothing on the flight. There is no benefit in a traveller wearing a well-fitted suit or dress if they are unable to rest well in it. A sleep mask, noise-cancelling earphones and a travel pillow can also help with rest. Travellers should avoid consuming a large, heavy meal or excess alcohol or caffeine on the flight, and they should drink plenty of water and keep as mobile as possible.

It is fine to sleep during a flight if this occurs seven to eight hours before the planned bedtime at the destination. Otherwise, naps should be kept to less than 30 to 45 minutes. For multistage flights, sleeping is ideally done on the longest leg.

Travelling east

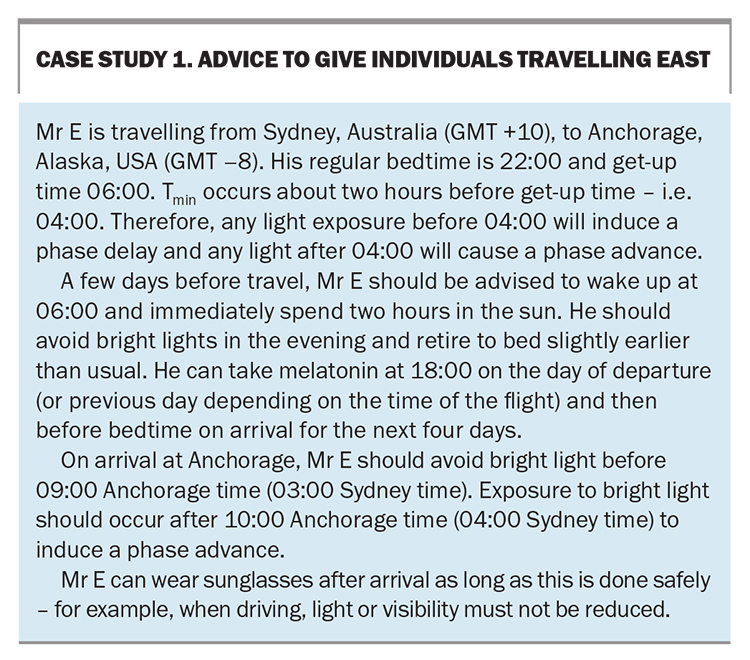

The goal when travelling east is to phase advance (Case study 1). To achieve this, the traveller will have to go to sleep at the destination earlier than they are used to.

Efforts to advance the circadian rhythm can start a few days before travel at the traveller’s place of origin. Exposure to bright light on awakening and avoiding light exposure in the evening is crucial. Although certain artificial light sources, such as light visors, dawn simulators, desk lamps or light boxes, are available that provide a high level of lux (unit of illuminance), natural sunlight works as well. Exposure to between 30 and 90 minutes of light is sufficient. Aim to dim the lights earlier in the night to bring forward the time of melatonin onset.

On arrival at the destination, bright light should be avoided early in the morning as this will occur before Tmin and cause a phase delay. Exposure to bright light can occur in the late morning to induce a phase advancement.

Furthermore, on the day of departure (or previous day depending on time of the flight) melatonin can be taken at 18:00 local time and then at the local bedtime 22:00 on arrival for four further days.8

Travelling west

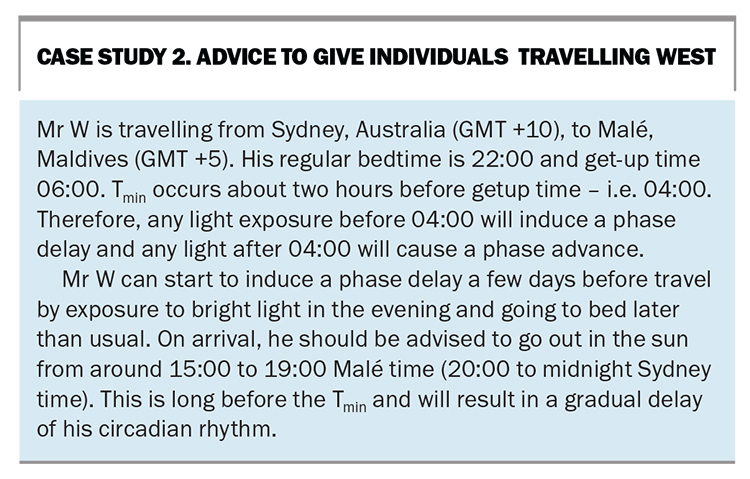

The goal when travelling west is to phase delay (Case study 2). To achieve this, the traveller will have to go to sleep at the destination later than they are used to.

Again, treatment can be started before travel. Exposure to bright light in the evening will start to induce a phase delay.

On arrival at the destination, the traveller should have bright light exposure in the later afternoon and early evening. Melatonin may not be required in westward travel, depending on number of time zones crossed.

Therapeutic approaches

Melatonin

Melatonin is often used in conjunction with timed light therapy, primarily for eastward travel to help advance the circadian rhythm. Daily dosages ranging from 0.5 to 5 mg have been found to be useful for circadian rhythm sleep disorders.9,10 Extended-release formulations (2 mg/day) are readily available.

Melatonin is reasonably well tolerated and is considered a relatively safe drug in most patient populations.11 Back pain and arthralgias are the most common side effects. Melatonin is best taken right before bedtime at the destination city for three to four days.

In Australia, melatonin is available over the counter for primary insomnia in adults aged 55 years and over, and by prescription for younger patients.

Of note, melatonin can be obtained from other countries via the internet or found in health supplements. The dose, quality and bioavailability of these products are not standardised and not approved by the TGA. We do not recommend obtaining melatonin by this method.

Sedatives

The use of sedatives is limited and usually reserved for debilitating jet lag-associated insomnia.

Benzodiazepines (e.g. temazepam) and nonbenzodiazepines hypnotics (e.g. zolpidem) can improve time to sleep onset and duration but will not reduce the other effects of jet lag. They are associated with several side effects, including dizziness, confusion, nausea and lethargy, which can outweigh the limited benefits. For long journeys, they may be used at the start of the flight to ensure sleep is achieved as far away as possible from the destination bedtime. Contraindications include hypersensitivity, concurrent therapy with P450 inhibitors and severe hepatic insufficiency. In addition, these medications have the potential to worsen respiratory failure and sleep apnoea.

First-generation antihistamines, such as promethazine and doxylamine, can be obtained over the counter at local pharmacies. Although they provide a sedative effect, several significant adverse reactions, including anticholinergic effects, extrapyramidal reactions, neuroleptic malignant syndrome and orthostatic hypotension, may occur. We do not recommend their use in jet lag.

Stimulants

Although its evidence to counteract jet lag is limited, caffeine may be used to promote alertness when travelling east. However, its benefits must be weighed up against its propensity to disrupt sleep. Taking slow-release caffeine for five days may hasten the rate of circadian entrainment or alignment after eastward travel. If used, caffeine or caffeinated drinks should be consumed when at the destination.

Other wakefulness agents, such as armodafinil and modafinil, should be reserved for sleep specialist use and are usually prescribed for other sleep disorders.

Conclusion

Jet lag is a potential common side effect of travelling across time zones. Poor sleep, lethargy and other symptoms can derail holiday plans. Knowledge of an individual’s circadian rhythm, understanding the direction of travel and timing of light exposure can be used before travel to alleviate these effects. Treatment can start before travel and may involve pharmacological agents such as melatonin. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Rigney G, Walters A, Bin YS, Crome E, Vincent GE. Jet-lag countermeasures used by international business travelers. Aerosp Med Hum Perform 2021; 92: 825-830.

2. Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders - third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest 2014; 146: 1387-1394.

3. Lee Y, Field JM, Sehgal A. Circadian rhythms, disease and chronotherapy. J Biol Rhythms 2021; 36: 503-531.

4. Welsh DK, Takahashi JS, Kay SA. Suprachiasmatic nucleus: cell autonomy and network properties. Ann Rev Physiol 2010; 72: 551-577.

5. Münch M, Bromundt V. Light and chronobiology: implications for health and disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2012; 14: 448-453.

6. Zhu L, Zee PC. Circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Neurol Clin 2012; 30: 1167-1191.

7. Heywood AE, Watkins RE, Iamsirithaworn S, Nilvarangkul, MacIntyre CR. A cross-sectional study of pre-travel health-seeking practices among travelers departing Sydney and Bangkok airports. BMC Pub Health 2012; 12: 321.

8. Beaumont M, Batéjat D, Piérard C, et al. Caffeine or melatonin effects on sleep and sleepiness after rapid eastward transmeridian travel. J Appl Physiol 2004; 96: 50-58.

9. Sletten TL, Magee M, Murray JM, et al. Efficacy of melatonin with behavioural sleep-wake scheduling for delayed sleep-wake phase disorder: A double-blind, randomised clinical trial. PLoS Medicine 2018; 15(6): e1002587.

10. Mundey K, Benloucif S, Harsanyi K, Dubocovich ML, Zee PC. Phase-dependent treatment of delayed sleep phase syndrome with melatonin. Sleep 2005; 28: 1271-1278.

11. Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Hooton N, et al. Efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for secondary sleep disorders and sleep disorders accompanying sleep restriction: meta-analysis. BMJ 2006; 332: 385-933.