Managing COPD in general practice: the role of the COPD Clinical Care Standard

There are significant gaps between evidence-based practice and the care provided to people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Australia. The COPD Clinical Care Standard supports best practice in the assessment and management of people with COPD and aims to reduce preventable hospitalisations and improve overall patient outcomes.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common chronic condition with significant disease burden.

- There is an 18-fold variation in hospitalisation rates for COPD between local areas, indicating an inequity in resources and the availability and quality of care between different geographical areas.

- The COPD Clinical Care Standard describes the healthcare that people can expect to receive if they are at risk of developing, or currently have, COPD.

- GPs play an important role in implementing best-practice COPD care.

Large gaps exist between evidence-based care and real-world clinical practice in the field of respiratory medicine, resulting in a significant health burden both in Australia and globally.1 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is among the top five chronic conditions causing disease burden in Australia, and people with COPD generally rate their health worse than people without the condition. The highest burden of disease associated with COPD is seen among those living in rural and remote areas and among those living in areas of greatest disadvantage (i.e. low-socioeconomic areas).2

COPD was the sixth leading overall cause of death in Australia in 2022 after coronary heart disease, dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease), cerebrovascular disease, COVID-19 and lung cancer. In women aged 64 to 75 years, it was the second leading cause of death after lung cancer.2 In 2022, 10% of all deaths in Australia were recorded as caused by or associated with COPD.3 This article provides an overview of managing COPD in general practice, with a focus on the COPD Clinical Care Standard.

Clinical features of COPD

COPD, one of the more common chronic respiratory diseases in Australia, is a heterogenous lung condition characterised by chronic respiratory symptoms (e.g. dyspnoea, cough, sputum production and exacerbations) caused by abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) or alveoli (emphysema) that cause persistent, often progressive, airflow obstruction.4 Diagnosis is confirmed by evidence of airway obstruction on spirometry, with a postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio less than 0.7.5 Cigarette smoking is the major cause of COPD, with about half of all smokers developing some airflow limitation, and 15 to 20% developing clinically significant disability.6 Globally, many nontobacco risk factors contribute to the development of COPD, including the inhalation of toxic particles and gases from household and outdoor air pollution, as well as other environmental, occupational and host factors (including abnormal lung development and accelerated lung ageing).7,8

Progression can involve exacerbations, impaired exercise performance, health status deterioration and death. Management emphasises risk factor elimination, minimising exacerbation risk, self-management, continuous medication, personalised treatment plans and clinician engagement.9

Incidence of COPD

The rigorously performed Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) epidemiological study, which assessed symptoms and spirometry findings, found that nearly 8% of people in Australia aged 40 years and older had COPD in 2006–10.10 Studies such as the 2023 Australian Bureau of Statistics National Health Survey and the 2020–21 MedicineInsight program, representing 10.8% of practising GPs in Australia, each found the prevalence of either self-reported COPD or COPD recorded at any time in GP medical records was lower at 2.4 to 2.5%, suggesting significant underdiagnosis.2,11

Underdiagnosis is not unique to Australia; a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 21 studies from mostly high-income countries (including two from Australia) investigating COPD diagnosis in primary care settings documented a prevalence of undiagnosed COPD in 14 to 26% of symptomatic smokers and in about 25% of patients taking inhaled therapies.12 Conversely, there was also a 25 to 50% prevalence of COPD overdiagnosis, with the quantitative data suggesting that these included people who had fewer symptoms, were prescribed fewer respiratory medications, were younger and more obese compared with those with a correct diagnosis.12

About 10% of First Nations people aged 45 years and older were estimated to be living with COPD in 2018–19, based on the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health survey.13

The reasons for these higher rates of morbidity (and mortality) are complex and multifaceted but include the impacts of colonisation, systemic racism and lack of access to culturally safe healthcare.14

Role of the GP

GPs play an important role in diagnosing and managing COPD. Despite being a relatively common disease, especially in the older age group (an estimated 30% prevalence in people aged older than 75 years), and contributing to a high disease burden, data from the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health survey indicated that COPD was not a commonly managed condition in general practice, being the 14th most commonly managed chronic condition, with an estimated rate of 0.9 per 100 encounters.15 MedicineInsight data from 2020–21 revealed that hypertension, anxiety disorders and depression were managed about five times more frequently than COPD.11

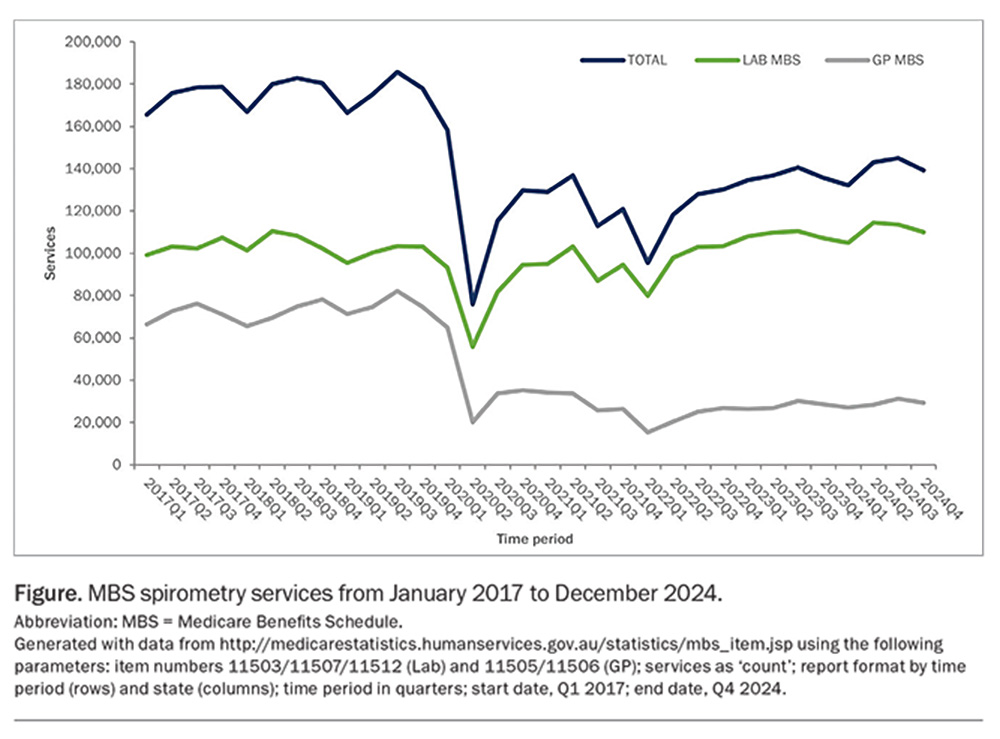

In Australia, despite relatively easy access to spirometry, as in many other high-income countries, testing is still insufficient, particularly in general practice.12,16,17 This worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, given that spirometry is regarded as an aerosol-generating procedure.18 Services Australia data revealed that Medicare Benefits Schedule spirometry billings have not returned to pre-pandemic levels, especially in the general practice sector and are not as yet compensated by increased testing in respiratory laboratories (Figure).19

Delayed diagnosis can have significant negative consequences on a patient’s health and quality of life. Although there are no reliable Australian data, international studies have shown that for many patients with COPD, the diagnosis is first made after hospitalisation during an acute exacerbation and usually when there has already been substantial lung damage and chronic treatments are less effective.20-22 Opportunities for these symptomatic patients to have the diagnosis confirmed at an earlier stage are often missed in general practice, where their COPD has potentially remained unrecognised for many years.23

Gaps in COPD care in Australia

For the past 20 years, Australian clinicians have had access to comprehensive evidence-based guidance for managing COPD: the COPD-X Plan, which is meticulously updated every quarter by a group of dedicated experts supported by Lung Foundation Australia.5,24 Since 2014, this robust guideline has also been précised into a more user-friendly document with practical recommendations suitable for primary care. This COPD-X Handbook (previously called the COPD-X Concise Guide) is also updated regularly.9 In addition, Lung Foundation Australia has developed readily accessible resources for all healthcare professionals, especially GPs, including training resources, COPD Action Plans, Stepwise Management of Stable COPD guideline, Exacerbation Algorithm, COPD Checklist and the COPD Medicines Chart.25 Nonetheless, there remain several areas of evidence–practice gaps in COPD diagnosis and management in Australia, including underdiagnosis, mainly because of the underuse of spirometry, and low (<10%) referral rates to pulmonary rehabilitation, despite strong evidence demonstrating its cost effectiveness.

Since 2017, there has been no nationally consistent primary healthcare data collection to monitor the provision of care by GPs; however, the MedicineInsight GP Snapshot on COPD from the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) provides insights into how COPD management in general practice in Australia compares with best-practice, evidence-based management (https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/

publications-and-resources/resource-library/

medicineinsight-gp-snapshot-copd).26 Details about the MedicineInsight program can be found in Box 1.

The snapshot reveals that smoking status was recorded for 96% of patients with COPD and 61% of current smokers were recorded to have been offered smoking cessation advice. Twenty-five percent of patients with COPD currently smoke compared with 9% of all patients, and 83% of patients with COPD are up to date with their influenza vaccination. Disappointingly, only about two in five patients with a listed diagnosis of COPD have had a spirometry test, despite national and international guidelines emphasising that COPD cannot be accurately diagnosed without spirometric testing.26 Misdiagnosis leads to the inappropriate use of medicines, unnecessary cost to patients and the healthcare system and potential delays in an even more serious diagnosis for some patients.

People with COPD often experience exacerbations, marked by a rapid worsening of symptoms, which may lead to hospitalisation. COPD is a leading cause of potentially preventable hospitalisations in Australia.27 The Fourth Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation identified up to an 18-fold variation in hospitalisation rates for COPD between local areas, suggesting inequity in both resources and the availability and quality of care across different geographical areas.28

It is not just the challenges and deficiencies in primary care sectors that contribute to the evidence–practice gap. For example, there is also evidence of high rates of inappropriate antimicrobial use for COPD exacerbations, especially in hospitals. This includes inappropriate antimicrobial choice, treatment duration and route of administration.29

Given the prevalence of COPD, these gaps in care exact an important toll on patients, the healthcare system and society, with complex barriers at the patient, provider and healthcare system levels contributing in itself to each gap in Australia and other high-income countries and across all healthcare sectors.1

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care

The ACSQHC is a corporate Commonwealth entity and part of the Health portfolio of the Australian Government. As such, it is accountable to the Australian Parliament and the Minister for Health and Aged Care. In 2006, the Council of Australian Governments established the ACSQHC to lead and co-ordinate national improvements in the safety and quality of healthcare. It commenced as an independent statutory authority on 1 July 2011, funded jointly by the Australian Government and by state and territory governments with its role, functions and responsibilities governed by the National Health Reform Act 2011.

Its purpose is to contribute to better health outcomes and experiences for all patients and consumers in Australia, and to improve value and sustainability in the health system by leading and co-ordinating national improvements in the safety and quality of healthcare. Within this overarching purpose, the ACSQHC aims to ensure people are kept safe when they receive healthcare and that they receive the healthcare they should. Key functions of the ACSQHC include developing national safety and quality standards; developing clinical care standards to improve the implementation of evidence-based healthcare; co-ordinating work in specific areas to improve outcomes for patients; and providing information, publications and resources about safety and quality.

Clinical care standards

The ACSQHC established the Clinical Care Standards program in 2013 to support clinical experts and consumers to develop clinical care standards on health conditions that would benefit from a national co-ordinated approach. A clinical care standard describes the care that patients should be offered by clinicians and healthcare services for a specific clinical condition, treatment, procedure or clinical pathway, regardless of where people are treated in Australia.

Clinical care standards aim to address unwarranted variations in healthcare or patient outcomes by increasing evidence-based healthcare. Unlike clinical guidelines, they focus on priority aspects of care and play an important role in the delivery of appropriate high-quality care.30 Clinical care standards contain:

- quality statements describing the care that a patient should be offered, regardless of where they are treated in Australia

- information for patients, clinicians and healthcare services about what each statement means

- indicators to help clinicians and healthcare services monitor the care described in the clinical care standard and to support local quality improvement.

In developing the clinical care standards, the ACSQHC uses the most up-to-date clinical guidelines and standards, information about gaps between evidence and practice, the professional expertise of clinicians and researchers and the perspectives of consumers. Each clinical care standard is developed by a topic working group comprising members who have the expertise and knowledge of current evidence and of the issues affecting the appropriate delivery of care and that are important to consumers. Each clinical care standard is supported by implementation resources for consumers, clinicians and health services, and in some cases, for Primary Health Networks.

The ACSQHC’s first Clinical Care Standard on antimicrobial stewardship was released in 2014 and, since then, a total of 19 Clinical Care Standards have been developed, with more currently in progress. In 2023, an evaluation report assessed the impact of three Clinical Care Standards: those for antimicrobial stewardship, hip fracture and delirium.31

The COPD Clinical Care Standard

In May 2023, the ACSQHC convened a multidisciplinary committee to write the Clinical Care Standard for COPD. The committee members included respiratory physicians, GPs, emergency medicine physicians, respiratory nurses, physiotherapists, clinical pharmacists and people living with COPD. The COPD Clinical Care Standard applies to both community-based and acute care settings where care within the scope of the standard is provided, including:

- primary healthcare services (e.g. general practices, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations and community pharmacies)

- secondary healthcare services (e.g. specialist respiratory clinics)

- tertiary healthcare services (e.g. hospital wards, emergency departments and outpatient clinics).

The COPD Clinical Care Standard is relevant to all healthcare practitioners, including GPs and members of the GP team, although not all of the quality statements in the Clinical Care Standard are applicable to general practice or other healthcare settings. The document emphasises that different strategies may be needed to implement the standard in rural and remote settings. It also acknowledges that discrimination and inequity are significant barriers to achieving high-quality health outcomes for some patients from culturally and linguistically diverse communities and, in particular, the need for cultural safety and equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

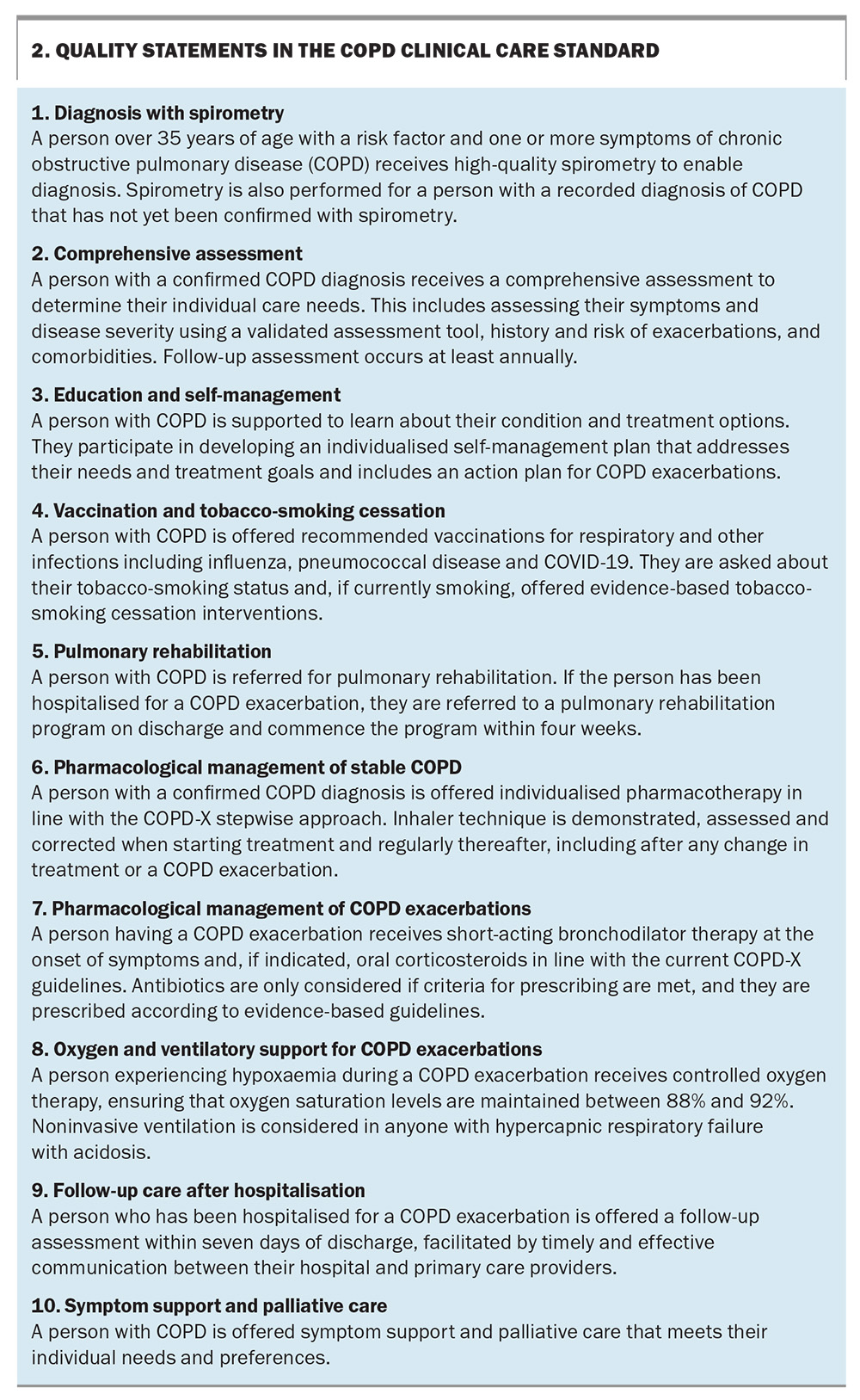

It also highlights considerations associated with the environmental impact of the care provided to patients. The stated goal of the COPD Clinical Care Standard is to reduce preventable hospitalisations and improve overall outcomes for people with COPD by supporting best practice in the assessment and management of COPD. There are 10 quality statements that describe the healthcare that should be provided to people living with COPD, extending from diagnosis to nonpharmacological and pharmacological management of stable COPD and the management of exacerbations and of end-of-life care (Box 2). Each quality statement is structured to show its purpose, what it means for patients, for clinicians and for healthcare services with an additional boxed section on cultural safety and equity, followed by relevant resources.

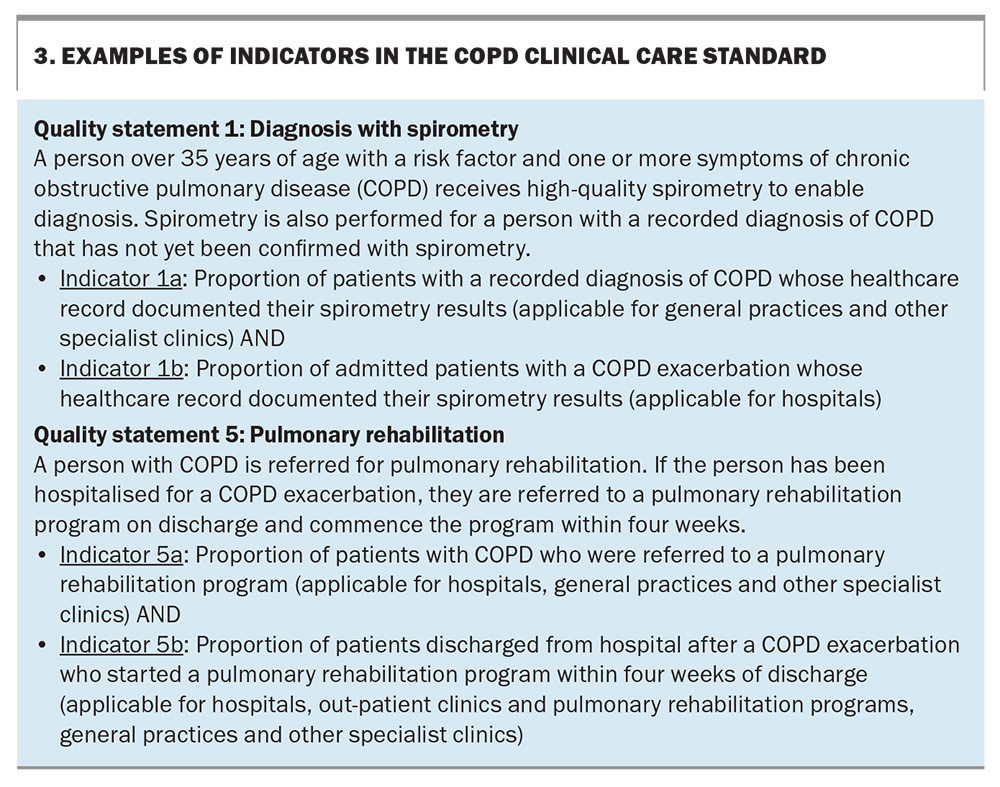

Accompanying these standards is a set of indicators for each quality statement to support clinicians and healthcare services to monitor how well they are implementing the care recommended in the standard and to support local quality improvement activities. On average, there are two to three indicators for each quality statement, noting whether the indicator is applicable to a particular setting (e.g. hospitals, general practices and other specialist clinics or outpatient departments). Some examples of indicators are provided in Box 3.

The COPD Clinical Care Standard was launched on 17 October 2024.32 It has been endorsed by 20 key clinical and consumer organisations. The Standard can be downloaded from the ACSQHC website (https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/clinical-care-standards/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-clinical-care-standard). Access to a YouTube video overview of the Clinical Care Standard by De Lee Fong (Medical Advisor ACQSHC and GP) is available (https://youtu.be/LhauM0wE3vI) with the launch webcast where the panel discussed the importance of accurate diagnosis with spirometry, pulmonary rehabilitation and a stepwise approach to pharmacotherapy (https://youtu.be/H4aLHrl2sEM).

Conclusion

It has long been recognised that there are significant gaps between evidence-based best practice care and the care that is provided to people with COPD in Australia. Innovative and multifaceted implementation approaches are needed to bridge these gaps and have the potential to make a large impact on the respiratory health of people in Australia. The COPD Clinical Care Standard highlights a range of evidence-based timely interventions that should help ease symptoms, reduce the risk of exacerbations and prevent hospitalisations for people with COPD. We all have a role to play in improving care for this significant chronic condition that affects many people in Australia. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Hancock was involved in developing and promoting the COPD Clinical Care Standard as a Member of the ACSQHC Topic Working Group (COPD); Chair of the Primary Care Clinical Council, Lung Foundation Australia; Member of the COPD Clinical Advisory Committee, National COPD Program, Lung Foundation Australia Member of the COPD-X Handbook Working Group; and Chair of the RACGP Respiratory Medicine Specific Interests Group.

References

1. Boulet LP, Bourbeau J, Skomro R, Gupta S. Major care gaps in asthma, sleep and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a road map for knowledge translation. Can Respir J 2013; 20: 265-269.

2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Canberra: AIHW; 2024. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-respiratory-conditions/copd (accessed February 2025).

3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Deaths in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2024. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life-expectancy-deaths/deaths-in-australia/contents/leading-causes-of-death (accessed February 2025).

4. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for prevention, diagnosis and management of COPD: 2025 report. Deer Park, IL: GOLD; 2025. Available online at: https://goldcopd.org/2025-gold-report/ (accessed February 2025).

5. Yang IA, George J, McDonald CF, et al. The COPD-X Plan: Australian and New Zealand Guidelines for the management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease 2024. Version 2.76, September 2024. Available online at: https://copdx.org.au/copd-x-plan/ (accessed February 2025).

6. Anto JM, Vermeire P, Vestbo J, Sunyer J. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2001; 17: 982-994.

7. Bui DS, Lodge CJ, Burgess JA, et al. Childhood predictors of lung function trajectories and future COPD risk: a prospective cohort study from the first to the sixth decade of life. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6: 535-544.

8. Yang IA, Jenkins CR, Salvi S. COPD in never smokers: pathogenesis and implications for prevention and treatment. Lancet Respir Med 2022; 10: 497-511.

9. Yang IA, Hancock K, George J, et al. 2024. COPD-X Handbook: Summary clinical practice guidelines for the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Milton, Queensland: Lung Foundation Australia; 2024. Available online at: https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/copd-x-handbook/ (accessed February 2025).

10. Toelle BG, Xuan W, Bird TE, et al. Respiratory symptoms and illness in older Australians: the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study. Med J Aust 2013; 198: 144-148.

11. NPS MedicineWise. General Practice Insights Report July 2020–June 2021. Sydney: NPS MedicineWise; 2022.

12. Perret J, Yip SWS, Idrose NS, et al. Undiagnosed and ‘overdiagnosed’ COPD using postbronchodilator spirometry in primary healthcare settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Resp Res 2023; 10: e001478.

13. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey. Canberra: ABS; 2019. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/national-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health-survey/2018-19 (accessed February 2025).

14. National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation and The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. National guide to preventive healthcare for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Recommendations. 4th edition. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP; 2024.

15. Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2015–16. General practice series no. 40. Sydney: Sydney University Press; 2016. Available online at: https://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/sup/9781743325131 (accessed February 2025).

16. Lim R, Smith T, Usherwood T. Barriers to spirometry in Australian general practice: a systematic review. Aust J Gen Pract 2023; 52: 585-593.

17. Perret JL, Zwar NA, Walters EH, et al. A chronic obstructive pulmonary disease risk assessment tool in preventive lung healthcare: an unmet need? Aust J Gen Pract 2023; 52: 595-598.

18. Borg BM, Osadnik C, Adam K, et al. Pulmonary function testing during SARS-CoV-2: an ANZSRS/TSANZ position statement. Respirology 2022; 27: 688-719.

19. Services Australia. Medicare item reports. Canberra: Services Australia; 2025. Available online at: http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp (accessed February 2025).

20. Calverley PM. COPD: early detection and intervention. Chest 2000; 117: 365S-371S.

21. Hunter LC, Lee RJ, Butcher I, et al. Patient characteristics associated with risk of first hospital admission and readmission for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) following primary care COPD diagnosis: a cohort study using linked electronic patient records. BMJ Open 2016; 6: e009121.

22. Balcells E, Antó JM, Gea J, et al. Characteristics of patients admitted for the first time for COPD exacerbation. Respir Med 2009; 103: 1293-1302.

23. Jones RCM, Price D, Ryan D, et al. Opportunities to diagnose chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in routine care in the UK: a retrospective study of a clinical cohort. Lancet Respir Med 2014; 2: 267-276.

24. Dabscheck E, George J, Hermann K, et al. COPD-X Australian guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2022 update. Med J Aust 2022; 217: 415-423.

25. Lung Foundation Australia. Resources. for health professionals. Milton, Queensland: Lung Foundation Australia; 2025. Available online at: https://lungfoundation.com.au/resources/?user_category=32 (accessed February 2025).

26. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). MedicineInsight GP Snapshot: COPD. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2024. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/medicineinsight-gp-snapshot-copd (accessed February 2025).

27. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Potentially preventable hospitalisations in Australia by small geographic areas, 2020–21 to 2021–22: data. Canberra: AIHW; 2024. Available online at: www.aihw.gov.au/reports/primary-health-care/potentially-preventable-hospitalisations-2020-22/data (accessed February 2025).

28. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). Fourth Atlas 2021. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2021. p. 69-86. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/healthcare-variation/fourth-atlas-2021 (accessed February 2025).

29. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). AURA 2023: fifth Australian report on antimicrobial use and resistance in human health. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2023. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/antimicrobial-resistance/antimicrobial-use-and-resistance-australia-aura/aura-2023-fifth-australian-report-antimicrobial-use-and-resistance-human-health (accessed February 2025).

30. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). About the Clinical Care Standards. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2023. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/clinical-care-standards/about-clinical-care-standards (accessed February 2025).

31. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC). Delivering on ‘right care, right place, right time’. How clinical care standards are improving health care in Australia: An evaluation report. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2023. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/delivering-right-care-right-place-right-time-how-clinical-care-standards-are-improving-health-care-australia-evaluation-report (accessed February 2025).

32. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Clinical Care Standard. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2024. Available from: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-clinical-care-standard-2024 (accessed February 2025).