Menopausal hormone therapy – Tips and pitfalls

Most women experience menopausal symptoms at midlife. Healthy ageing in women should involve identifying those who would benefit from menopausal hormone therapy to improve quality of life and long-term health outcomes.

Note

This article has been updated for Women’s Health Week 2024. The updated article is available here.

- During menopause, 75% of women experience symptoms of oestrogen deficiency, including vasomotor menopausal and urogenital symptoms.

- Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is indicated for these bothersome symptoms, as well as for the prevention of bone loss, and is the most effective treatment.

- The benefits of MHT outweigh the risks for most healthy symptomatic women when initiated before the age of 60 years or within 10 years of menopause.

- There are only a few strong contraindications for the use of MHT; it is not prohibited and can be used cautiously in women with high-risk conditions under specialist supervision.

- There is no mandatory age cut-off or end-point to the prescription of MHT; rather shared decision making between the woman and clinician as to safe, effective treatment options should guide decisions on commencing or continued use.

There appears to be a resurgent interest in healthy ageing in women, evident in an increasing body of lay media stories, and announcements of government funding towards menopause services. Menopause, or the permanent cessation of ovarian function, occurs naturally in most women at around the age of 51 years, and 75% of women experience menopausal symptoms. These symptoms are due to a declining level of serum estradiol, which also contributes to long-term adverse health sequelae seen in postmenopausal women. With the average female born in Australia today expected to live beyond 85 years of age, the need to optimise the health and quality of life of women as they age is compelling.1

This article reviews the use of menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), including the indications and options for prescription and potential risks of use, in healthy symptomatic women. It does not discuss MHT use in premature ovarian insufficiency, conservative measures and nonhormonal options for menopause treatment, as these are beyond the scope of the article.

What is menopause and what are the symptoms?

Menopause is defined as a woman’s final menstrual period, and is a retrospective diagnosis, usually based on signs and symptoms, which can only be determined after twelve months of amenorrhoea.2 Although the menopause is usually a clinical diagnosis, for women in whom premature ovarian insufficiency (also known as premature menopause) is suspected, supportive tests to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out other aetiologies, such as pituitary disease, particularly hyperprolactinaemia (which does not always present with galactorrhoea), include antral follicle count and follicle stimulating hormone, anti-Mullerian hormone and inhibin B levels.2,3

Globally, menopause occurs at an average age of 48.8 years, and at 51 years in a Caucasian population.2,4 Premature menopause describes menopause that occurs before the age of 40, and investigations and formal diagnosis are required in this group of women because of the increased morbidity and mortality associated with the diagnosis. Early menopause is menopause occurring in women between the ages of 40 and 45 years. The importance of a woman’s age at menopause goes beyond the consultation for review of her symptoms and consideration of MHT, as it influences health outcomes later in life.

Symptoms related to oestrogen deficiency include vasomotor menopausal symptoms (VMS), which include hot flushes, night sweats and mood disturbance, such as anxiety and depression, and urogenital symptoms, including vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) and vaginal dryness, with related dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction.5 Other common sequelae include sleep disturbance, arthralgia, myalgia, altered cognitive function and weight gain. It may be helpful to use a menopause score card, such as the Modified Greene Scale (available online at: menopause.org.au/images/stories/ infosheets/docs/ams_symptom_score_card.pdf) or the menopause-specific quality of life (MENQOL) questionnaire (https://eprovide.mapi-trust.org/instruments/menopause-specific-quality-of-life-questionnaire) when in a consultation with a woman at midlife to identify and categorise her symptoms and determine the effect of treatment or resolution of symptoms in follow-up appointments.

Oestrogen deficiency is associated with long-term adverse health effects, including bone loss, increased fracture risk and cardiometabolic disease. Although weight gain cannot be specifically attributed to the menopause transition, an increase in total body adipose tissue and in central adiposity which, together with adverse lipid effects and impaired endothelial function, are seen in postmenopausal women and contribute to an increasing risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus and certain cancers at midlife.5-7

When to consider treatment of menopausal symptoms

Most women experience menopausal symptoms; one in two have moderate to severe VMS, and more than one in four report moderate to severe symptoms of VVA.8 Despite this, only a small number receive MHT for bothersome symptoms. Misinterpretation of initial data from the 2002 Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials determined that the overall risks of MHT outweighed the benefits and resulted in a drastic reduction in MHT prescriptions because of fears of adverse outcomes, including increased risk of coronary heart disease and invasive breast cancer.4,9 Further research and subsequent analyses of the WHI data have informed medical practitioners and the public on the safe use of MHT. Nevertheless, careful consideration of the risks and benefits of MHT for each individual woman is key to shared decision-making about whether to initiate or continue it as a treatment option.

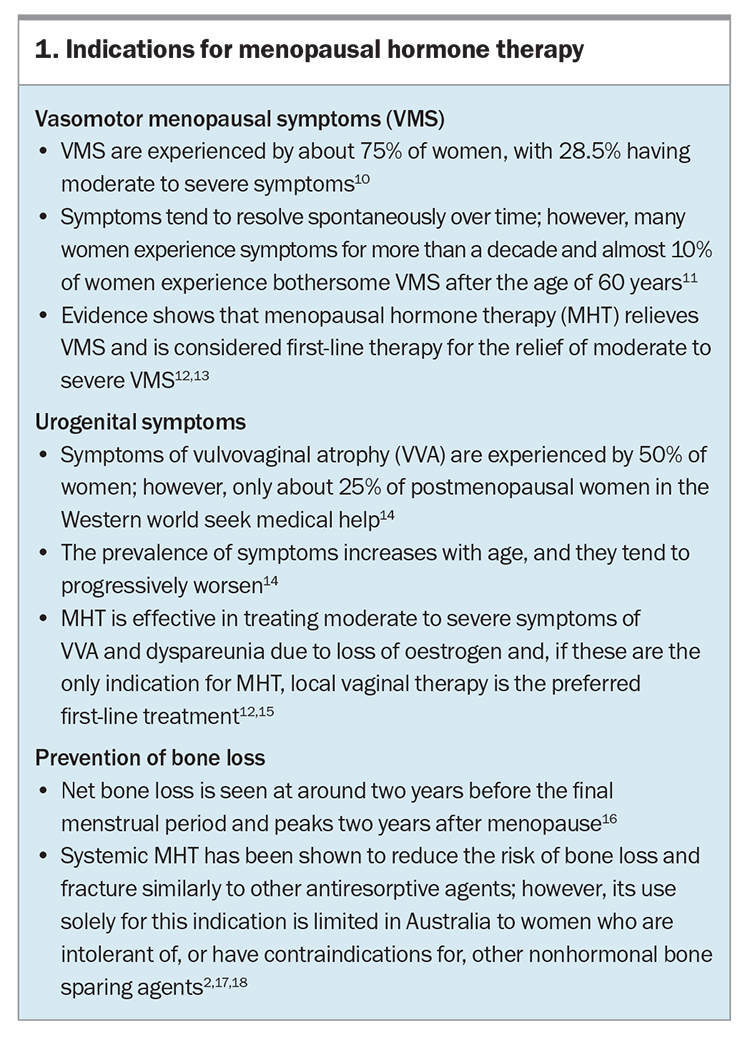

Indications for MHT include vasomotor symptoms, urogenital symptoms and preventing bone loss (Box 1).10-18 Although alleviating troublesome vasomotor symptoms remains the major indication for prescribing MHT, studies have shown improvements in other symptoms of menopause including sleep, mood changes, central adiposity and joint pain and stiffness.

Prescribing MHT

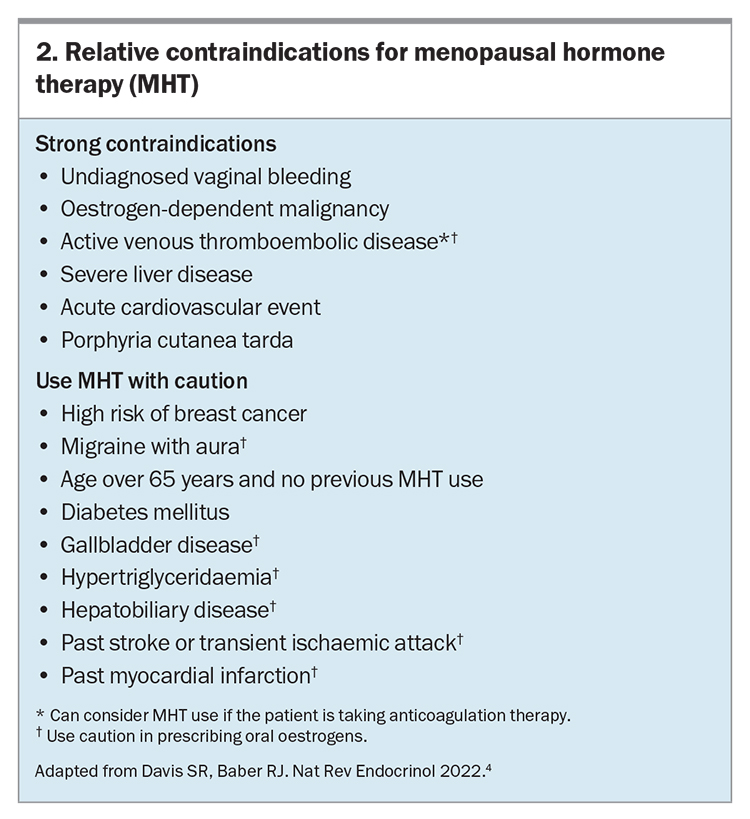

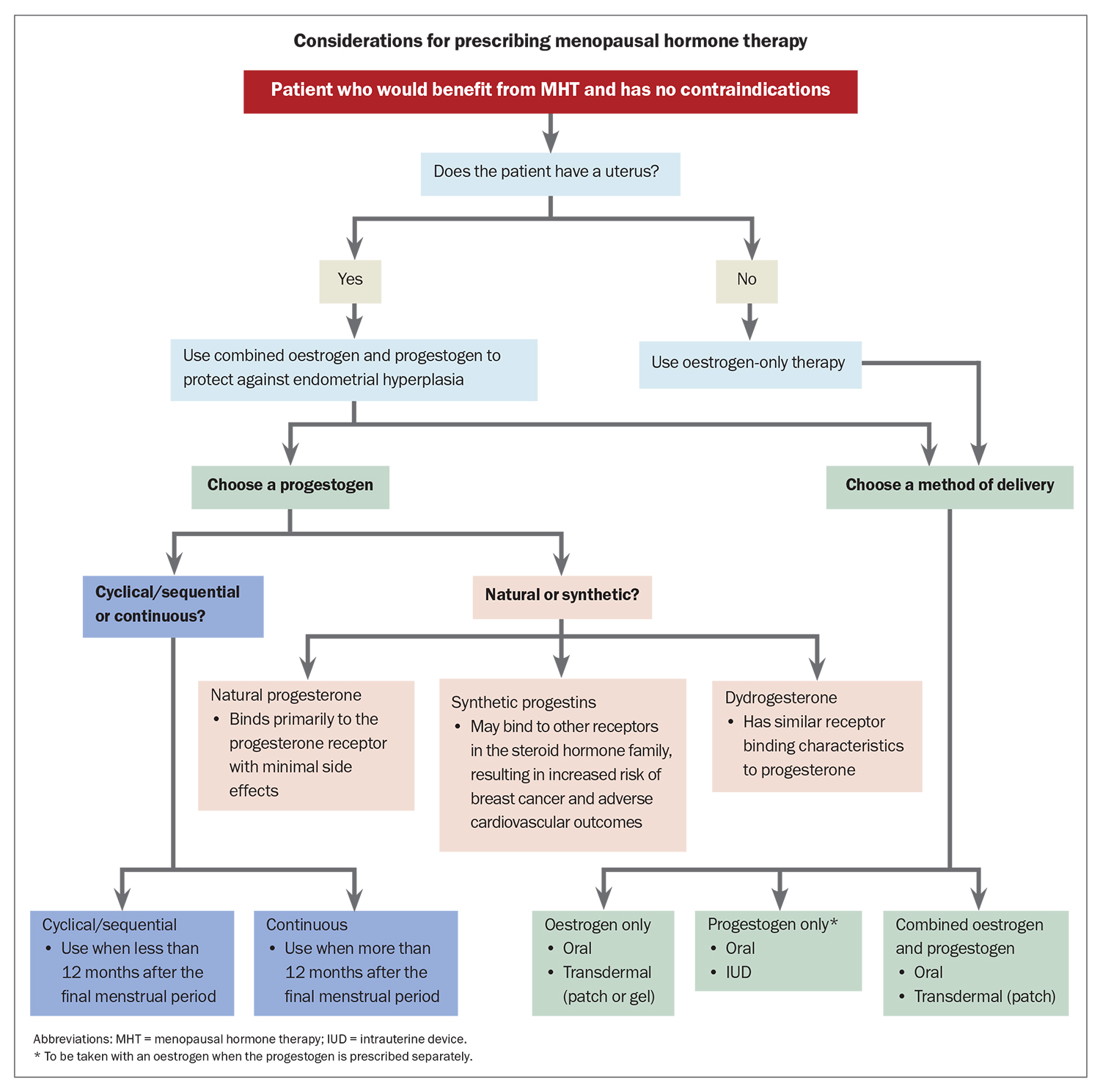

Once it is established that a woman would benefit from MHT and she has no contraindications to its use (Box 2), it is important to consider which hormones are most appropriate for each individual patient and the best method of delivery before prescribing treatment. Considerations for prescribing MHT are outlined in the Flowchart. For women without a uterus (i.e. who have had a hysterectomy), oestrogen-only therapy is appropriate. Women with an intact uterus must be prescribed a progestogen alongside an oestrogen to protect against endometrial hyperplasia. This can be achieved by choosing a fixed combination preparation or by prescribing an oestrogen and a progestogen separately. Progestogens are usually prescribed orally; however, the 52 mg levonorgestrel intrauterine system (IUS) is approved for use as a component of MHT for up to five years. Such approval does not apply to the lower dose 19.5 mg IUS.19

Estradiol may be delivered orally or transdermally. Transdermal administration is associated with a lower risk of thromboembolic disease and a more stable distribution of serum estradiol. Thus, transdermal therapy may be preferred for women who are older, at increased cardiovascular or thromboembolic risk, or who suffer from migraine headaches and mood disturbances. For some women, oral therapy is their preferred therapy choice, whereas for others, such as those who may not tolerate or respond to transdermal therapy, it may be the better option. Local vaginal oestrogen therapy is the preferred first-line treatment for women in whom VVA and dyspareunia are the only menopausal symptoms.

Cyclical/sequential oestrogen and progesterone is usually recommended for women who are within 12 months of their last menstrual period and results in a regular withdrawal bleed that should occur around the end of the progestogen phase of the cycle. Continuous combined MHT is usually prescribed for postmenopausal women and is often associated with unplanned bleeding or spotting during the first six months of therapy, after which any bleeding must be investigated.

When selecting a progestogen, it is important to consider whether a natural or synthetic product is more suitable for the woman. Progestogens bind to progesterone receptors and include:

- the natural hormone progesterone, which binds primarily to the progesterone receptor with minimal side effects

- synthetic progestins, which may bind to other receptors in the steroid hormone family to induce both desirable and undesirable side effects, and include norethisterone acetate, levonorgestrel, medroxyprogesterone acetate and drospirenone

- dydrogesterone (retroprogesterone), a retro isomer of progesterone with similar receptor-binding characteristics to progesterone.

Current international guidelines recommend the use of micronised progesterone or dydrogesterone over synthetic progestins in MHT where possible, in combination with oestrogen, to minimise adverse cardiovascular and breast effects.2

Tibolone is a synthetic steroid classified as a selective tissue oestrogenic activity regulator which has oestrogenic, progestogenic and androgenic effects. Tibolone is taken orally and can cause irregular bleeding if commenced earlier than 12 months after the last menstrual period. It should therefore only be used in women who have had a hysterectomy or after 12 months of amenorrhoea.4 Tissue selective estrogen complex is a new class of agent that combines conjugated estrogens 0.45 mg and bazedoxifene 20 mg and is taken orally; however, it is not currently available in Australia.

Hormone therapy should be commenced at a low dose and uptitrated to relieve symptoms. An exception to this advice is for women with primary ovarian insufficiency, who should be started on a standard bone-sparing dose (e.g. 2 mg estradiol, 50 mcg patch) and who may need higher doses to achieve complete relief of symptoms and bone protection. When considering dosage, clinicians and women must acknowledge the principle of using the lowest effective dose of MHT to mitigate risks. Care should include periodic re-evaluation at least every year to review the benefits and risks of continuing therapy.12

MHT is not contraceptive and contraception is recommended for two years after the final menstrual period for women aged under 50 years and for one year for those aged over 50 years.19 Appropriate contraceptive options include barriers (important for safe sex), intrauterine devices and permanent measures such as bilateral salpingectomy. The combined oral contraceptive pill remains an option for perimenopausal women, unless contraindicated.

What are the risks of MHT?

Shared decision making with women and discussing risks and benefits is key when initiating and continuing MHT.12 Before initiating MHT, women should be screened for cardiovascular and breast cancer risk, along with a thorough medical history and examination focused on elucidating any potential contraindications.20

The North American Menopause Society position statement on hormone therapy, published earlier in 2022, summarises the potential risks for women aged younger than 60 years, including:12

- breast cancer – rare with combined oestrogen and progesterone therapy

- endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer – only occurs with inadequately opposed oestrogen

- venous thromboembolism – with oral oestrogen therapy

- gallbladder disease, particularly with oral oestrogens.

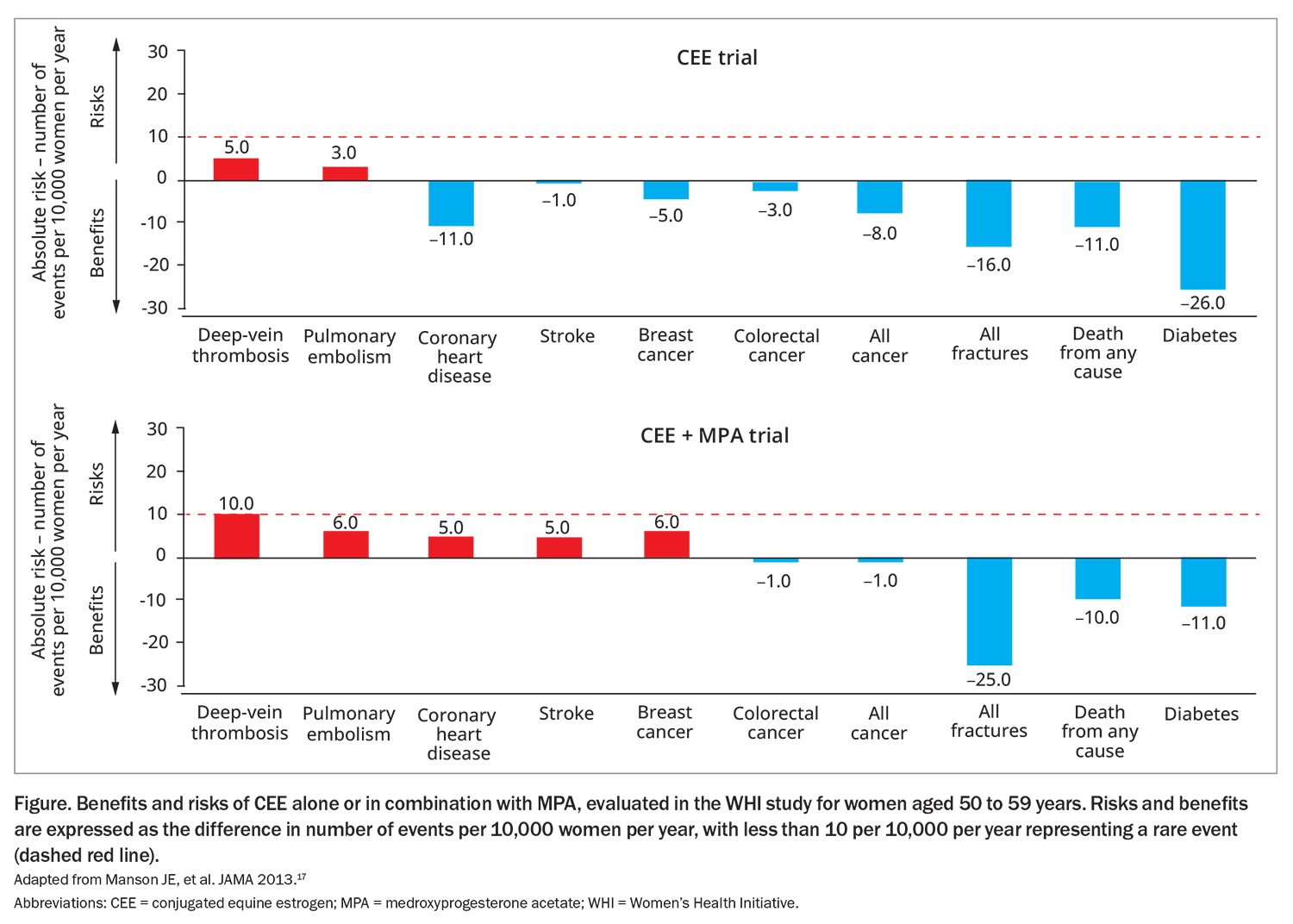

The absolute risk of these conditions is considered rare. Follow up from the WHI study looked at the risk of several conditions in women aged 50 to 59 years using conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) alone or in combination with medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) (Figure).12,17 In patients using combined CEE and MPA therapy, there were six additional cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women compared with non-users.17 Similarly, an additional 10 cases of deep vein thrombosis and six cases of pulmonary embolism occurred among those using combined therapy. Risks for adverse events appear lower for oestrogen-only therapy and when a natural progestogen (rather than a synthetic such as MPA) was used for combined therapy.

Bleeding on MHT

In women with an intact uterus, unopposed oestrogens are known to increase the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. This is prevented by the addition of an appropriate dose of progestogen.21 Women using sequential oestrogen–progestogen therapy should bleed towards the end of the progestogen phase of their regimen. Bleeding that is out of cycle, prolonged or heavier than expected requires investigation. Women commenced on continuous combined MHT may experience some unexpected bleeding or spotting during the first six months of therapy and any bleeding beyond this should also be investigated.

Appropriate investigations include taking a history, examination, transvaginal ultrasound scan to assess endometrial thickness and, if the endometrium is not clearly seen on ultrasound or is more than 5 mm thick, tissue sampling.22 Among women who continue to bleed on continuous combined MHT in the presence of a thin endometrium, a hysteroscopy and biopsy are indicated to exclude the possibility of type 2 endometrial cancer. If results from investigations are normal, changing the MHT dose or delivery method can be considered.

When should MHT be stopped?

International guidelines do not support a mandatory limitation on the duration of MHT use.4,12 MHT offers maximum benefits and minimum risks in healthy symptomatic postmenopausal women when it is initiated within 10 years of the last menstrual period or between the ages of 50 and 59 years. This benefit to risk ratio is lower in women who initiate MHT after the age of 60 years or more than 10 years from their last menstrual period. At annual review, an assessment of the need to continue therapy is based on the persistence of recognised indications, such as VMS and the level of bone loss, combined with evaluation of individual risk factors. Conversion from oral to transdermal delivery and possible dose reduction should be considered as age increases.

Conclusion

Most women experience menopausal symptoms at midlife, with a large proportion reporting that these symptoms are bothersome. MHT is the most effective treatment for bothersome symptoms, with few risks and compelling evidence for short- and long-term physical and psychological health benefits. Shared decision-making that takes into account the risks and benefits for each woman as well as personal preference is essential to achieve the best treatment outcomes. ET

COMPETING INTERESTS: None

References

1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Life tables: statistics about life tables for Australia, states and territories and life expectancy at birth estimates for sub-state regions, 2018 – 2020. ABS; Canberra, 2021. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/life-tables/2018-2020 (accessed October 2022).

2. Baber R, Panay N, Fenton A, et al. 2016 IMS Recommendations on women’s midlife health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric 2016; 19: 109-150.

3. Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al; STRAW +10 Collaborative Group. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Climacteric 2012; 15: 105-114.

4. Davis SR, Baber RJ. Treating menopause – MHT and beyond. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022; 18: 490-502.

5. Davis SR, Lambrinoudaki L, Lumsden M, et al. Menopause. Nat Rev Dis 2015; 1: 15004.

6. Davis SR, Castelo-Branco C, Chedraui P, et al. Understanding weight gain at menopause. Climacteric 2012; 15: 419-429.

7. Poehlman E, Toth MJ, Gardner A. Changes in energy balance and body composition at menopause: a controlled longitudinal study. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123: 673-678.

8. Worsley R, Bell RJ, Gartoulla P, Davis SR. Low use of effective and safe therapies for moderate to severe menopausal symptoms: a cross-sectional community study of Australian women. Menopause 2016; 23: 11-17.

9. Rossouw J, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative Randomised Controlled Trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 321-333.

10. Gartoulla P, Worsley R, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Moderate to severe vasomotor and sexual symptoms remain problematic for women aged 60 to 65 years. Menopause 2015; 22: 694-701.

11. Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al; Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175: 531-539.

12. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2022; 29: 767-794.

13. Maclennan AH, Broadbent JL, Lester S, Moore V. Oral oestrogen and combined oestrogen/progestogen therapy versus placebo for hot flushes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; (4): CD002978.

14. Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 2010; 13: 509-522.

15. Biehl C, Plotsker O, Mirkin S. A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of vaginal estrogen products for the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Menopause 2019; 26: 431-453.

16. de Villiers TJ, Gass MLS, Haines CJ, et al. Global Consensus Statement on Menopausal Hormone Therapy. Climacteric 2013; 16: 203-204.

17. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended post stopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310: 1353-1368.

18. Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100: 3975-4011.

19. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH). FSRH guideline: contraception for women aged over 40 years. 2017 (Amended September 2019). FSRH; UK; 2019. Available online at: https://www.fsrh.org/documents/fsrh-guidance-contraception-for-women-aged-over-40-years-2017/ (accessed October 2022).

20. Bateson D, McNamee K. Perimenopausal contraception: a practice-based approach. Aust Fam Physician 2017; 46: 372-377.

21. Barrett-Connor E, Slone S, Greendale G, et al. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Study: primary outcomes in adherent women. Maturitas 1997; 27: 261-274.

22. Carugno J. Clinical management of vaginal bleeding in postmenopausal women. Climacteric 2020; 23: 343-349.