Flashes and floaters: symptoms not to be ignored

Flashes and floaters are common among older people but can belie a more serious condition. Judicious evaluation, including an ocular history and a visual assessment, can help identify an underlying pathology. Referral to a specialist is important for early diagnosis, treatment and potential prevention of blindness.

Flashes and floaters are common in an ageing population and are often described as being a nuisance. However, they can be symptoms of a more serious underlying pathology, and recognising their cause is important. A prompt referral to an eye care professional is essential for early diagnosis and prevention of blinding ocular pathology. A detailed history, assessment of visual acuity and dilated fundus examination provides clues to identify the pathology. This article discusses the common and serious underlying causes of flashes and floaters, punctuated by a series of case studies.

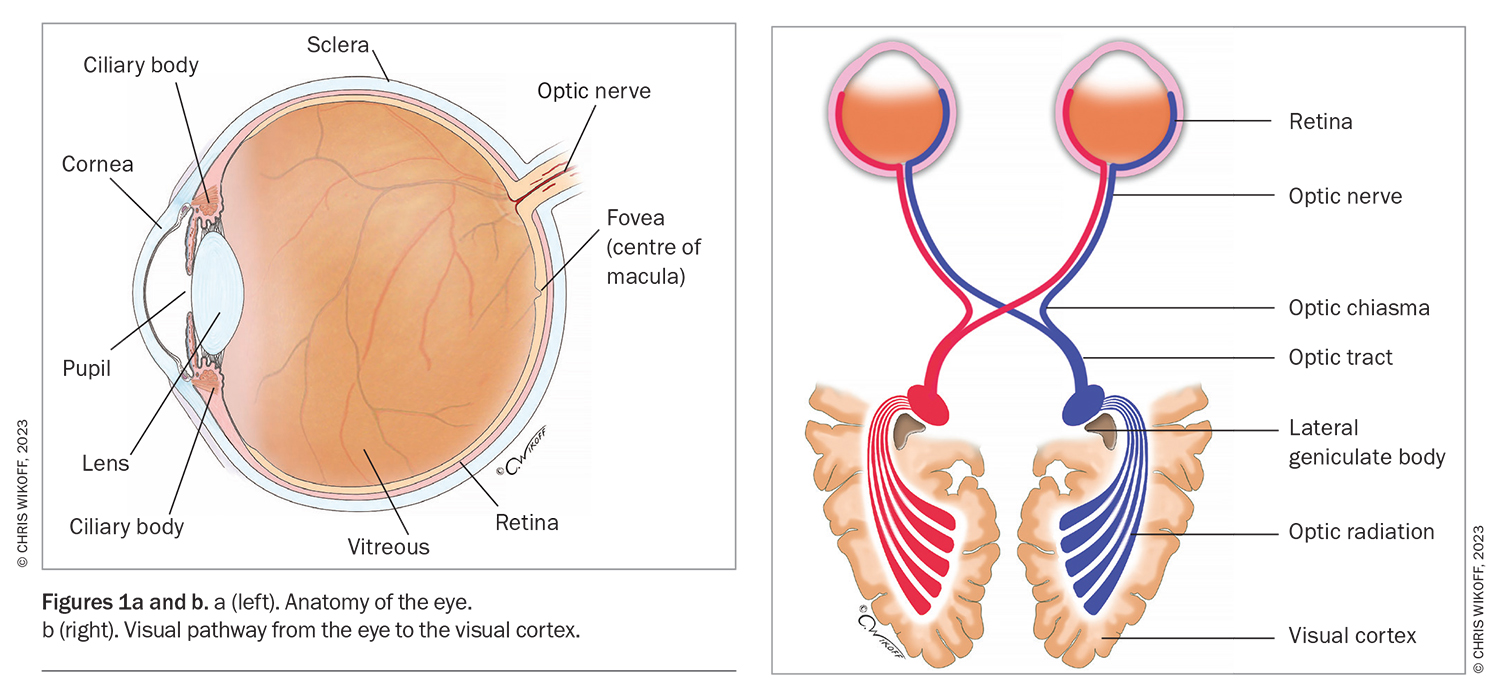

Anatomy of vitreous and the visual pathway

The vitreous is a clear gel made of collagen, soluble proteins, hyaluronic acid and water that fills the interior of the vitreous cavity (Figure 1a).1 It allows light to pass through the eye to the neural retina and plays an important role in regulating oxygen levels and distribution within the eye.2 Vitreous syneresis and condensation occur with age as the collagen structures naturally liquefy. Light enters the eye by passing through the cornea, lens and vitreous, to the retinal tissue. The light focused on the retina is transmitted as neural impulses through the optic nerve to the occipital lobe of the brain, where it is perceived as an image. The perception of symptoms can be the result of any lesion along the visual pathway (Figure 1b).

Flashes

Flashes, also known as photopsias, are caused by mechanical stimulation of the retinal neurosensory tissue and result in images of light. Stimulation of the neural retina, such as a traction of the vitreous separating from the retina may cause flashes. These can be described as different patterns, such as fleeting arcs of light, zigzag appearance or colourful geometric shapes. Rare but serious causes of flashes include enlarging choroidal tumours and metastases.

Symptoms of flashes can also arise from stimulation of the visual pathway to the brain. This stimulation can be due to a relatively benign pathology, such as ocular migraines, or to more serious autoimmune lesions affecting the retina, such as melanoma-associated retinopathy or cancer-associated retinopathy. The latter can produce flashes described as drops of water running down the inside of a shower screen.

Floaters

A floater is an opacity within the vitreous gel. It is often perceived as a fly or cobweb appearance. With increasing age, the collagen matrix within the gel becomes condensed and liquefied, resulting in the symptoms of floaters as the path of light entering the eye is scattered and a shadow is cast on the retina.

The clear vitreous gel may become opacified by impregnation of red blood cells seen in vitreous haemorrhages. It may also be opacified by white cells seen in inflammation and infection. Benign calcium-lipid deposits can be found in a condition called asteroid hyalosis. In rare instances, malignant cells, such as lymphoma, may be seen in the vitreous. It is important to assess the vitreous carefully to exclude these blinding and life-threatening conditions.

Posterior vitreous detachment

Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) is the separation of the posterior vitreous cortex and neurosensory retina. This common condition occurs with increasing age. As the vitreous gel liquefies, the adhesion of the vitreous to the retina becomes weaker.3 Patients will typically present with symptoms of a peripheral flashing light described as ‘lightning arcs’. Floaters described as spots or cobwebs may also be present. Symptoms become worse with head movement and photopsia is more obvious in dark surroundings.

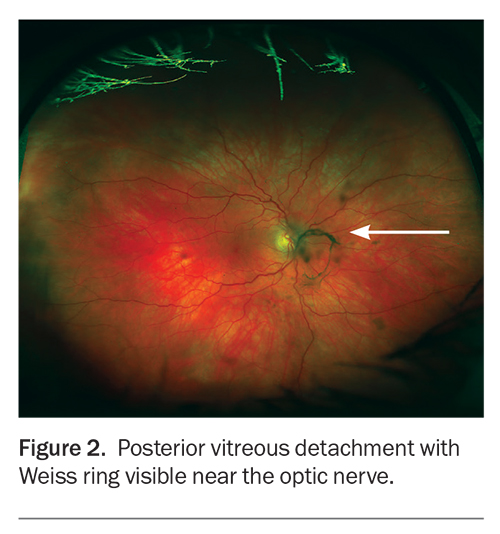

When examining the fundus, a finding of a Weiss ring suggests a PVD is present (Figure 2). A Weiss ring has an appearance of a circular ring-shaped opacity from the peripapillary condensation of vitreous gel that was attached to optic nerve.

Most cases of age-related PVD are uncomplicated and do not cause loss of sight. However, it is essential to consider referral to an eye care professional for a dilated fundus examination to exclude retinal tears and detachment. New retinal tears may still occur four weeks after the onset of symptoms. If a patient reports more intense flashes and changes in the nature of floaters, urgent review should be undertaken to exclude retinal tear and detachment. Surgical repair may be performed to prevent blindness.

Retinal tear

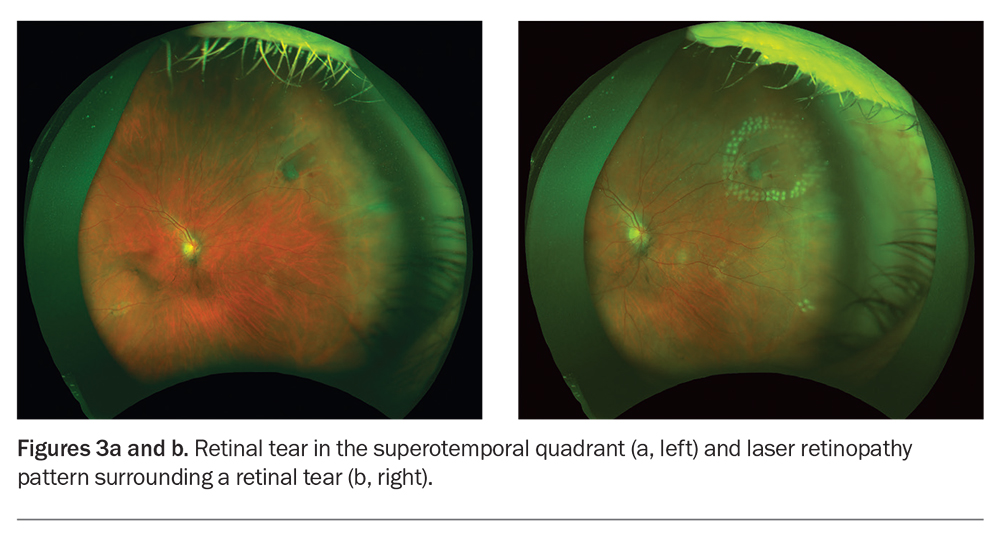

One of the complications of a PVD is the development of a retinal tear. This is caused by traction by the vitreous on the retina at the vitreoretinal junction. Retinal tears occur in 7 to 15% of patients who have a PVD.4,5 Patients may complain of floaters secondary to the vitreous debris and flashes caused by the vitreous traction on the neural retinal layer. Patients with a suspected tear must be immediately referred to an ophthalmologist for a dilated fundus examination to identify and repair the tear. Treatment involves laser to surround the tear and prevent progression to retinal detachment (Figure 3).

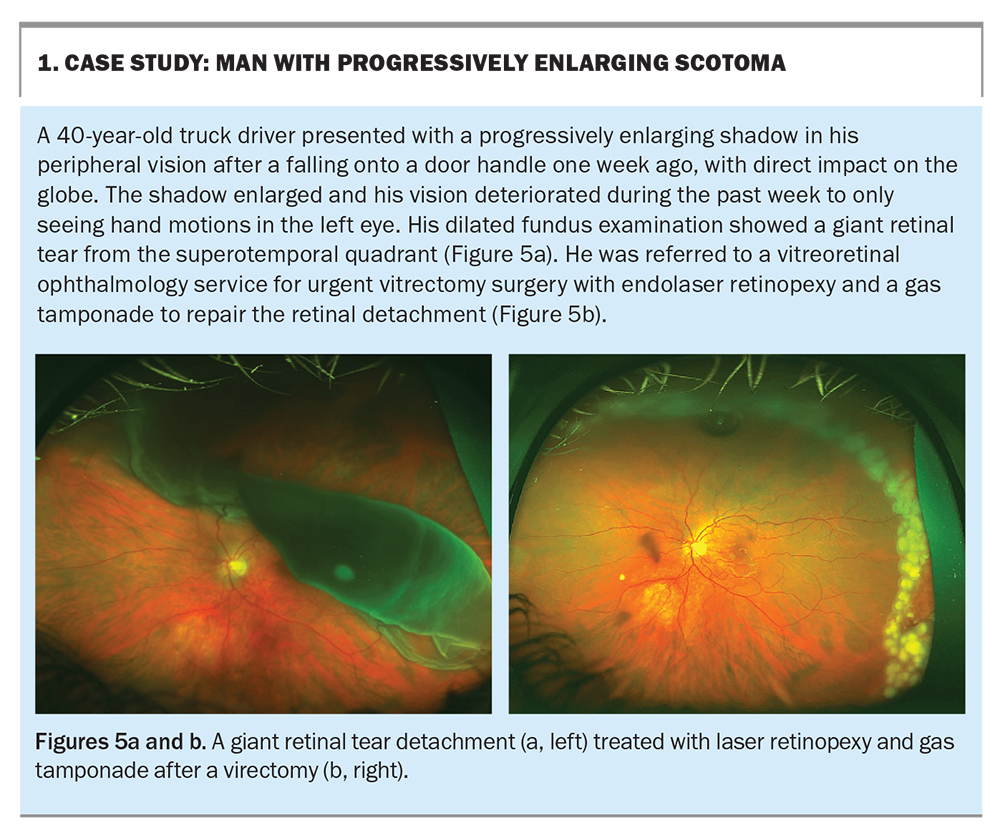

Retinal detachment

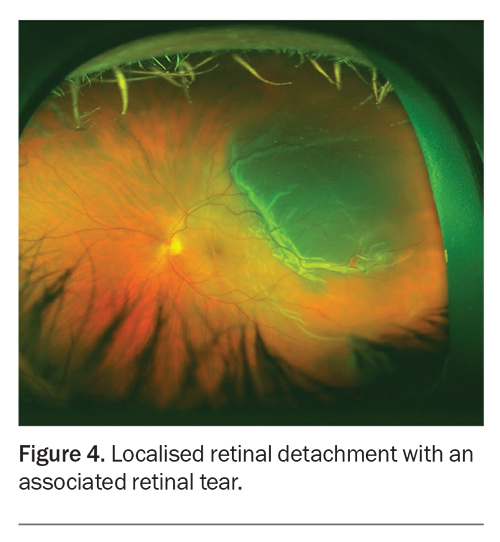

If retinal tears are not treated in a timely manner, the natural progression evolves to a retinal detachment (Figure 4). The liquefied vitreous enters the retinal break and the retina is lifted with progressive detachment. Patients with retinal detachment describe a pattern of symptoms of flashing lights and floaters, followed by a curtain-like shadow starting from the periphery and progressing to involve the entire visual field. This is an ocular emergency and surgical repair should be undertaken as soon as possible.

Trauma accounts for 10% of causes of all retinal detachments.1 Other risk factors for retinal detachment include increasing age, near-sightedness (myopia), a history of retinal detachment and areas of retinal weakness (lattice degeneration). If retinal tears or detachments are identified, patients should be urgently referred to a vitreoretinal service for repair as any delays in treatment can result in blindness (Box 1).

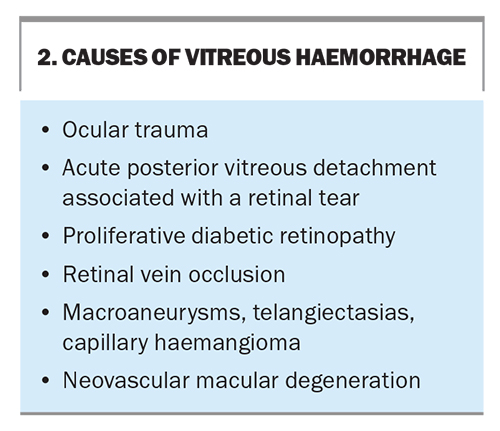

Vitreous haemorrhage

A vitreous haemorrhage can initially present as a floater in a mild haemorrhage, and progress to rapid blindness in a dense haemorrhage. Common causes of vitreous haemorrhages are outlined in Box 2. Examination of the fundus may be difficult given the opacities that often obscure the view. Referral to an ophthalmologist for an ultrasound scan (B-scan) allows for identification of abnormalities in the posterior segment.

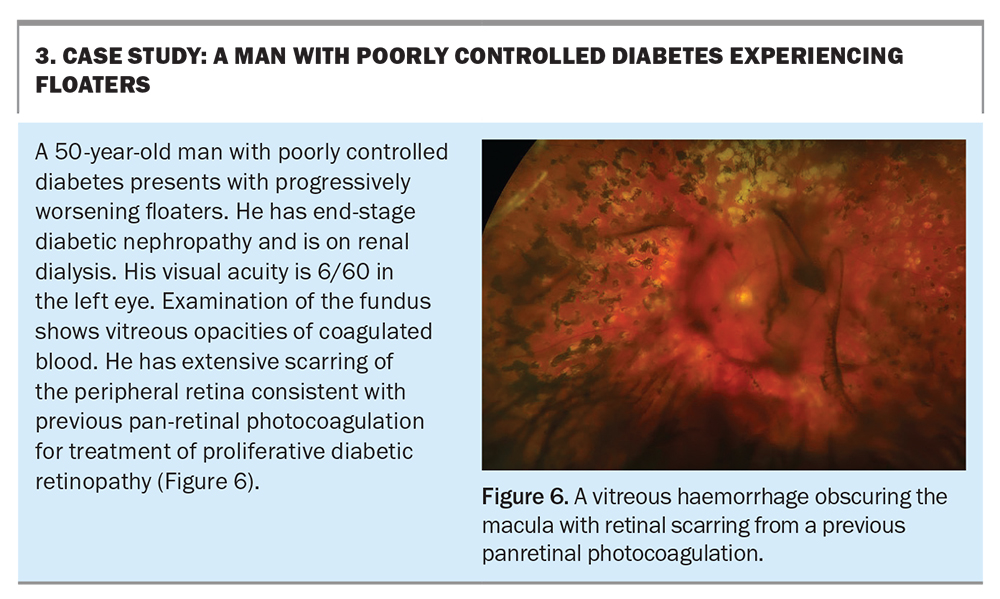

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Poorly controlled diabetes can result in a vitreous haemorrhage. The most important risk factors for progression of proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) are the duration and poor control of the diabetes.1 Treatment for PDR is by photocoagulation of the peripheral retina, known as panretinal photo- coagulation (PRP). Antivascularendothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) intravitreal therapy can be considered as an adjunct treatment to PRP.

Referral to an ophthalmologist should be considered. In cases of severe persistent vitreous haemorrhage and tractional retinal detachment threatening the central macula and vision, pars plana vitrectomy surgery should be undertaken (Box 3).

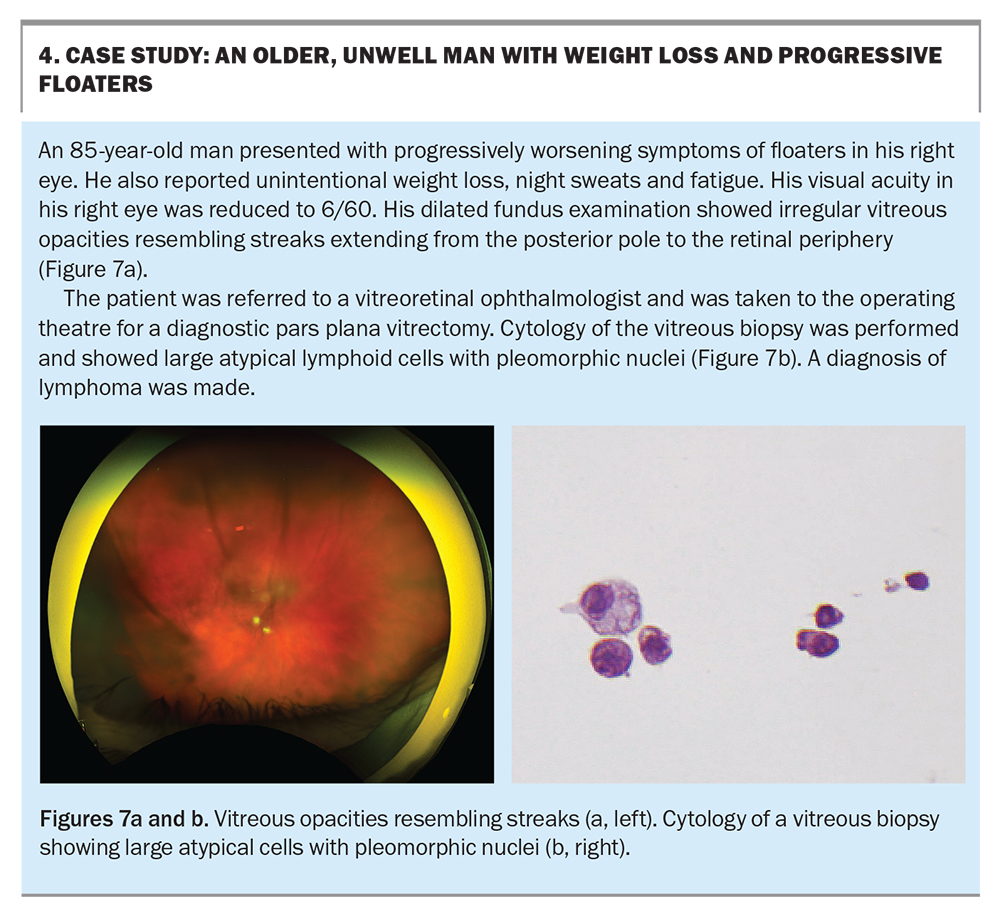

Lymphoma

Primary intraocular lymphoma is a rare but serious malignancy that arises from the central nervous system. It is estimated to represent 4 to 6% of primary central nervous system lymphomas.6 Symptoms at presentation are usually described as unilateral floaters and blurred vision, and are caused by clumps of vitreous cells, which is characteristic of the disease (Box 4).

If an intraocular lymphoma is suspected, a multidisciplinary approach to management should be considered, including a vitreous biopsy to confirm the diagnosis. A lumbar puncture and neuroimaging can assess the extent of central nervous system involvement. Treatment varies depending on the subtype of the disease, but radiotherapy of the eye and brain is often indicated.

Floaters may be the initial presenting symptom of lymphoma. Early diagnosis and treatment are not only sight saving but also lifesaving.

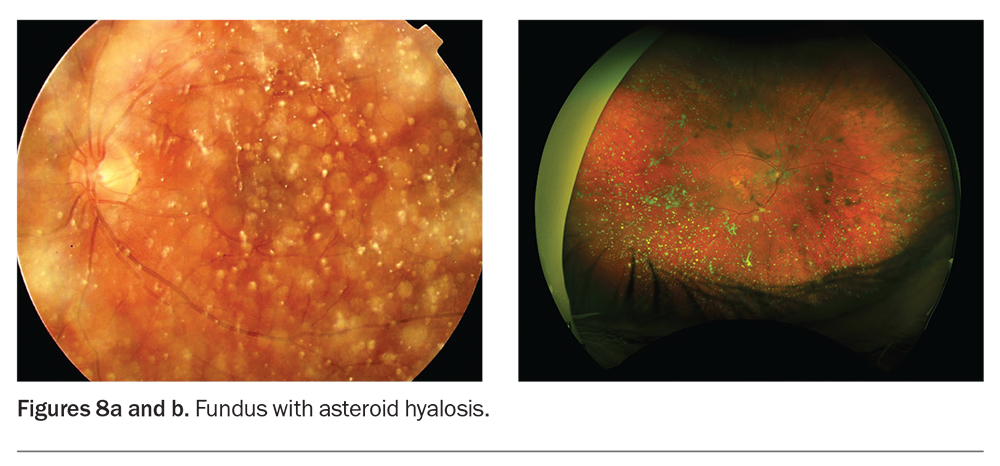

Asteroid hyalosis

Asteroid hyalosis is a benign and common degenerative condition with crystal formation that may cause floaters (Figures 8a and b).7 In Australia, the incidence of asteroid hyalosis in the general population is 1%.8 It has been found to be more prevalent in patients with diabetes, posterior vitreous detachments, age-related macular degeneration, hypertension and atherosclerosis.9

These opacities are comprised of calcium pyrophosphate particles that precipitate within the vitreous gel, which move with the vitreous during eye movements and do not sediment inferiorly. Surprisingly, it is unusual for patients with asteroid hyalosis to report floaters and concurrent pathology should be considered when sight is affected. Treatment with pars plana vitrectomy surgery can be considered if a patient is symptomatic.

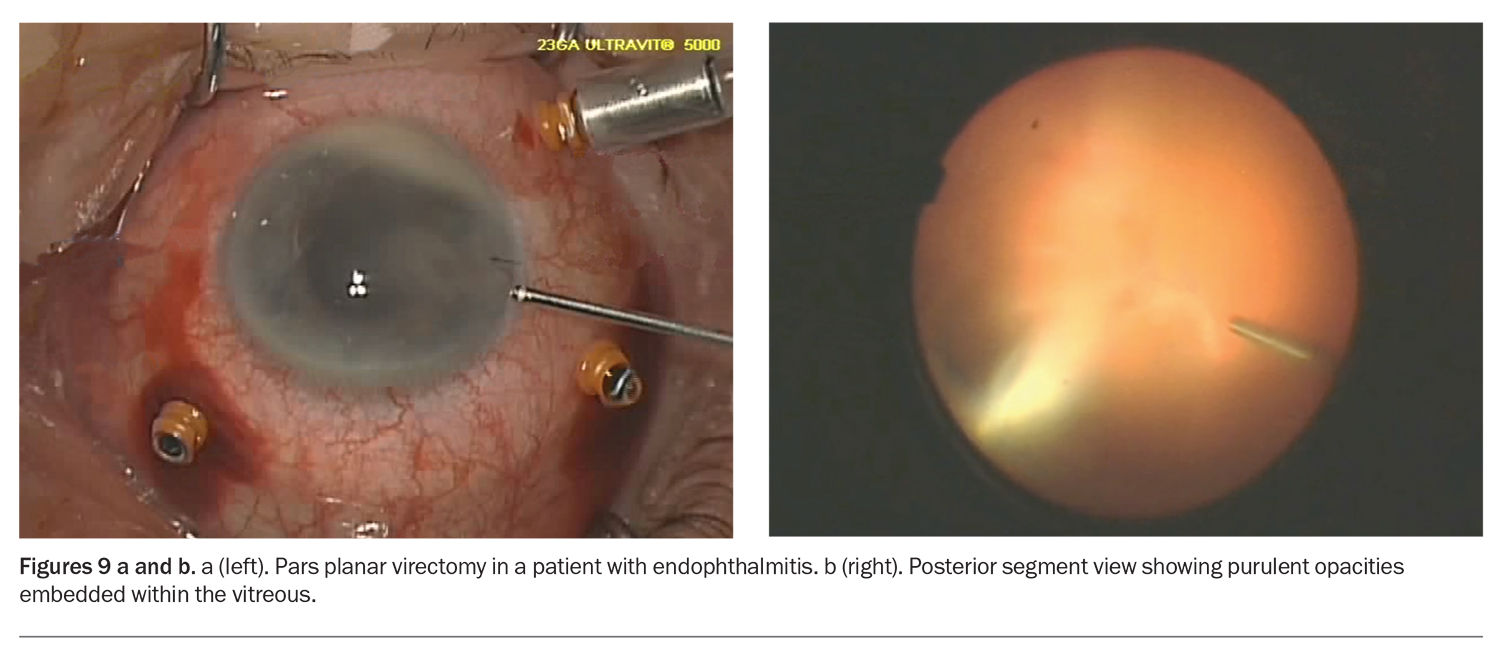

Inflammation

In purulent infective causes of floaters, such as endophthalmitis, inflammatory cells and abscesses fill the vitreous cavity. A red eye, pain and decreased vision should raise suspicion of a severe intraocular infection. Emergency referral to a specialist for treatment is required, as this can be a rapidly progressive condition.

Exogenous endophthalmitis can occur within days after a surgical ocular procedure (e.g. intravitreal injection or intraocular surgery) or ocular trauma. In the case of traumatic endophthalmitis, a high index of suspicion for a retained intraocular foreign body must be considered.

Endogenous endophthalmitis may occur in acutely unwell or recently hospitalised patients, and in those who are immunocompromised or intravenous drug users. These patients would have no history of recent intraocular procedures. Patients with candida chorioretinitis with vitreous involvement may need hospitalisation for systemic antibiotic treatment.

Opacities can form in cases of uveitis where the vitreous is inflamed. These floaters are made up of a collection of inflammatory cells with the appearance of snowballs.

Pars plana vitrectomy

Vitrectomy surgery is a microsurgical technique that uses small-gauge instruments to access the posterior segment of the globe (Figures 9a and b). Patients with retinal tears and detachments are treated with laser and cryotherapy to repair the areas of the tear. It is now the standard of care for treatment on the vitreous and retina. Vitreous gel is removed and replaced with balanced saline solution or a gas bubble. The gas bubble exerts a tamponade effect on the areas of treatment for further healing postoperatively. In cases of symptomatic vitreous opacities, a vitrectomy can be performed to remove the vitreous along with the embedded opacities.

Laser vitreolysis

In the clinic setting, a laser can be used to evaporate and dissect vitreous opacities. Although the procedure has a relatively good safety profile, variable results of clinical benefit have been found.10,11

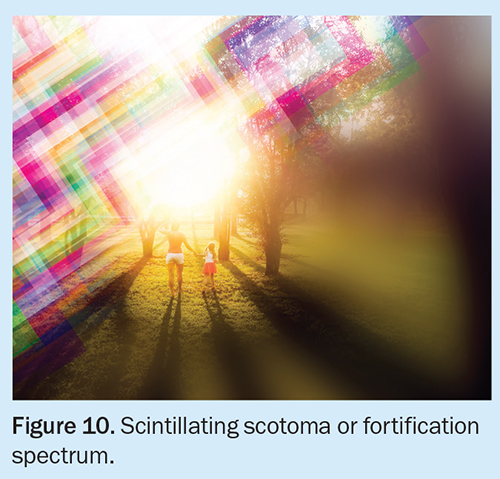

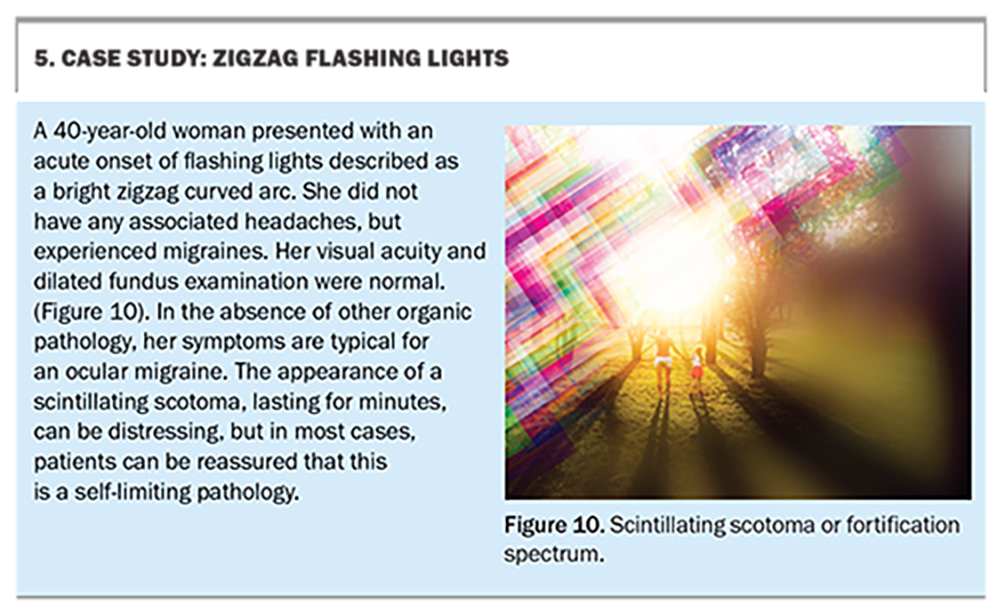

Migraine and ocular migraine

A general migraine with typical aura affects both eyes but may be perceived as unilateral. Patients may describe varying levels of flashes, floaters and vision loss, which is reversible. These symptoms can last for many hours.

An ocular, or retinal, migraine is a variant of general migraines. A patient history will often suggest the diagnosis. Patients often describe a unilateral, fully reversible, scintillating scotoma, usually in the retinal periphery, which extends over the visual field (Figure 10), lasting 10 to 15 minutes and slowly resolving in the reverse manner as the visual loss started. Ocular migraine is more often seen in younger women with a previous history of migraines (Box 5). It is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, and consideration of appropriate investigations to exclude transient monocular blindness must be completed.

Treatment of a general migraine or ocular migraine involves avoiding the inciting trigger. Pharmacological treatment can be considered in consultation with a neurologist.

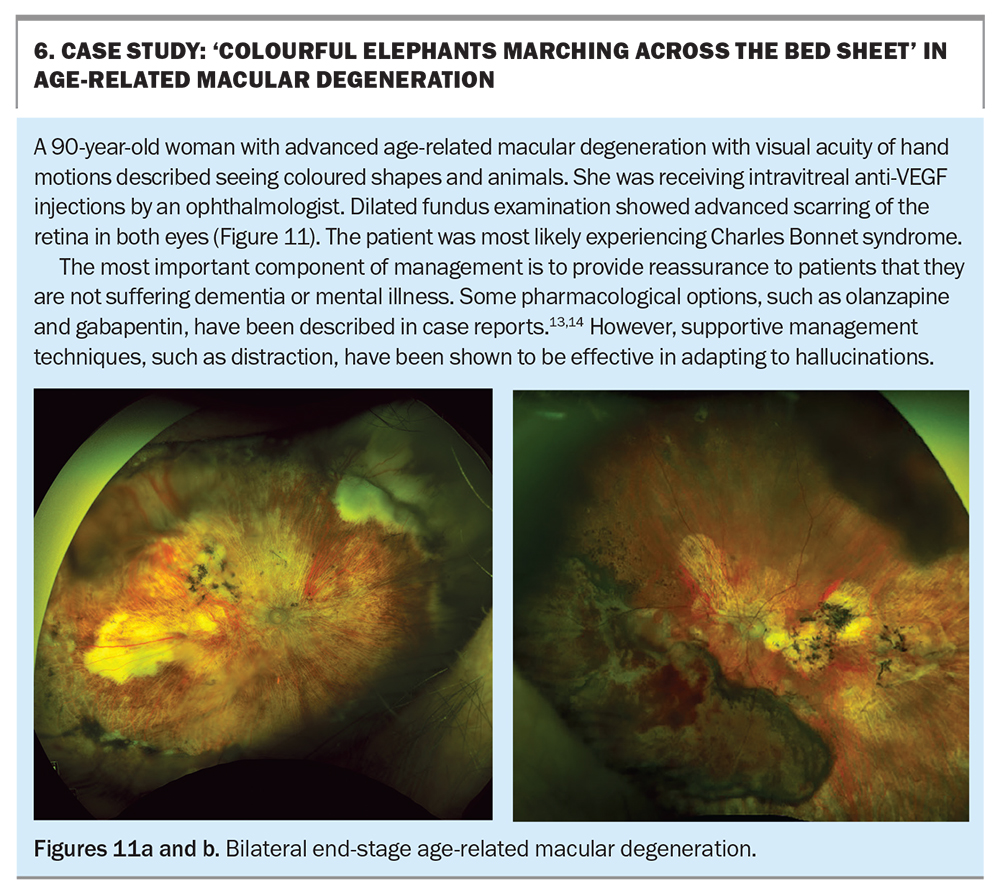

Charles Bonnet syndrome

Charles Bonnet syndrome is a condition that affects patients with low vision. It is commonly seen in patients with age-related macular degeneration in which mechanical scarring of the macula stimulates retinal tissue and is interpreted by the brain as images and light. Although it is commonly characterised by vivid, elaborate and recurrent visual hallucinations in psychologically normal people, it has a wide spectrum of descriptors (Box 6). Patients have described shapes, dots of colour, people, animals and picturesque scenery. The prevalence of this condition has been reported to be up to 17% in patients with visual acuity less than 6/12.12

Awareness of Charles Bonnet syndrome is poor among patients with low vision. As hallucinations may be very distressing for patients, they should be warned that this is common after vision loss, particularly in age-related macular degeneration. They should be also reassured that this is not a sign of dementia or mental illness. Although Charles Bonnet syndrome has no cure, there are distracting techniques patients may use to adapt by changing the inciting conditions or closing the eyes. There have been case reports improving symptoms of hallucinations in patients after using gabapentin or olanzapine.13,14

Retinal examination techniques and instruments

A patient history can often give clues to a patient’s perceived flashes and floaters. A recent study has shown that a simple questionnaire can predict the risk of a retinal tear or detachment in patients with symptoms consistent with a PVD.15 However, it is important to examine the posterior segment of the eye as it is often diagnostic for pathology.

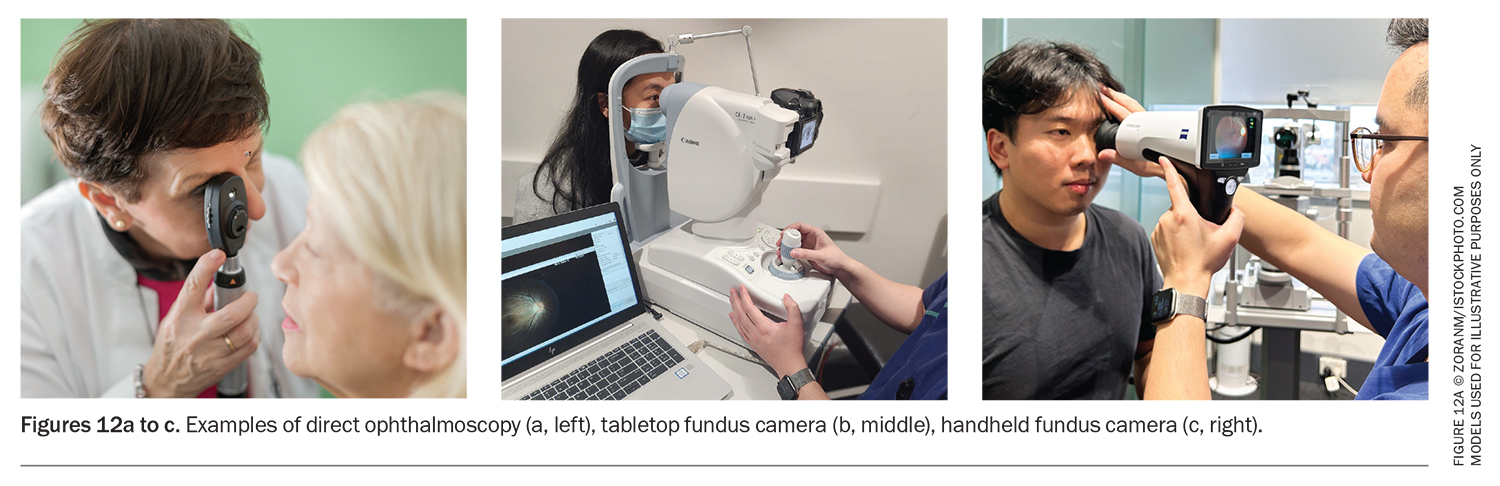

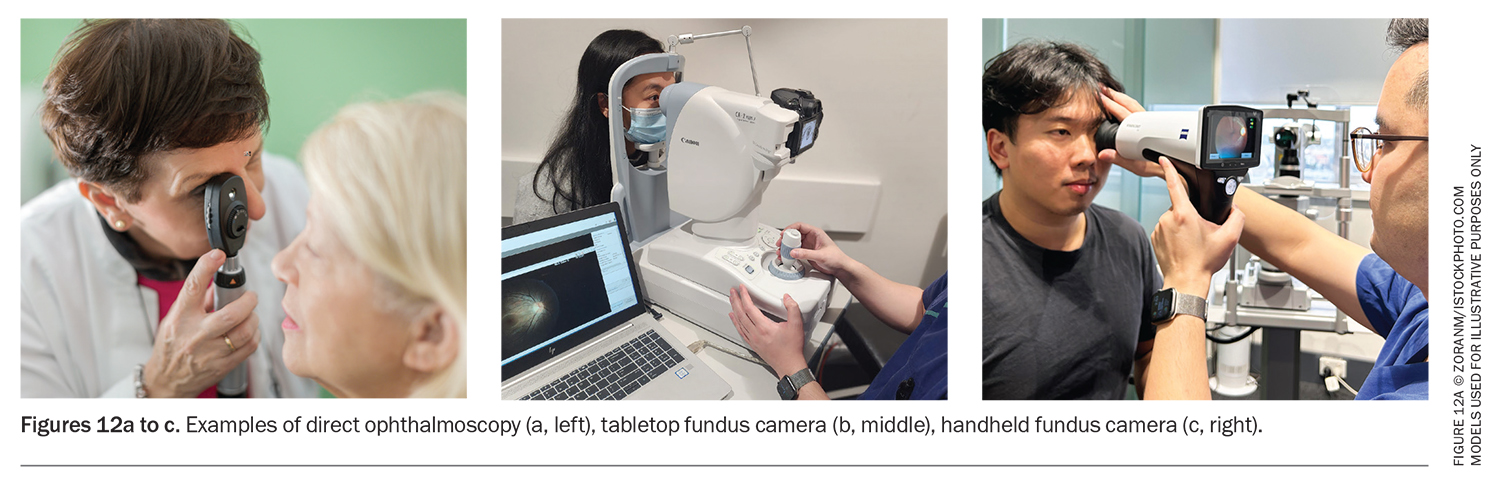

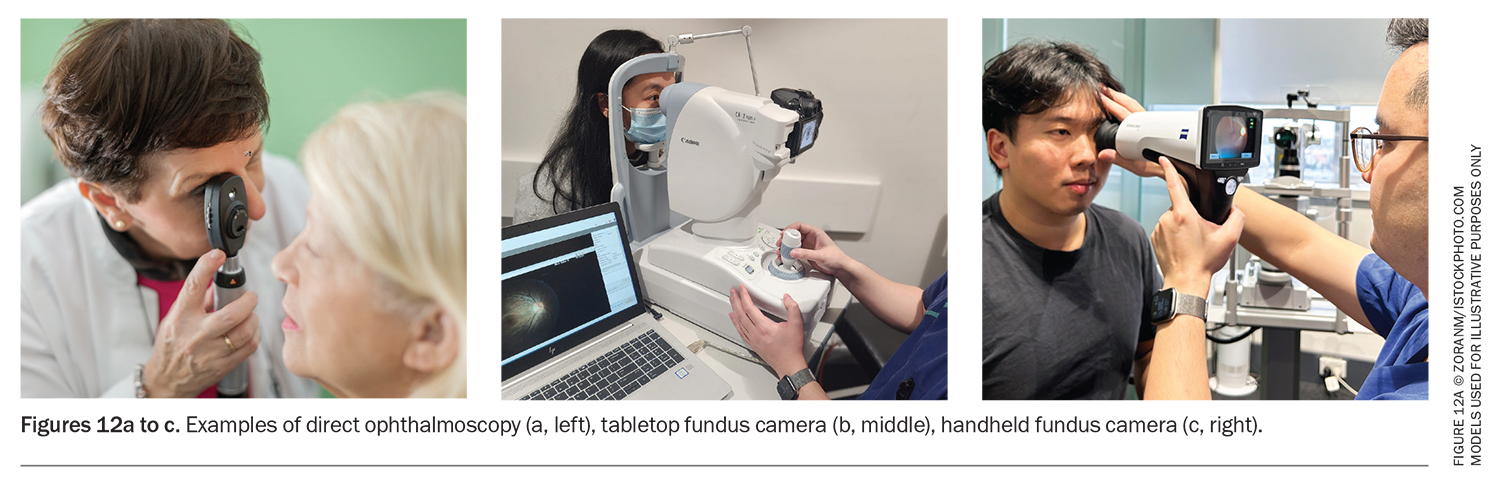

A direct ophthalmoscope is an accessible instrument for examining the vitreous and retina (Figure 12a). Dilation of the pupils can be achieved with tropicamide drops.

Advances in photographic imaging technology include tabletop fundus cameras that can capture high-resolution, wide-angle fundus photos of the retina (Figure 12b). These cameras are often found at specialist eye care practices. Handheld colour fundus cameras are affordable and portable and can capture images of the posterior segment with high fidelity, identify pathology and allow for documentation in continuity of care (Figure 12c).

Conclusion

The acute nature of flashes and floaters will be distressing to patients. For most patients, the symptoms may settle and represent a benign pathology. However, acute changes or exacerbation of the ‘usual’ symptoms should raise the concern of blinding or life-threatening conditions. Patients should be advised to report an increase in symptoms, reduced visual acuity (which should intermittently be checked by the patient) or the development of a peripheral scotoma.

A patient history, including characteristics of the symptoms and ocular and medical disease history, may point to the diagnosis. Assessment of visual acuity and examination of the vitreous and retina with direct ophthalmoscopy are useful in diagnosing and referring pathology, including retinal detachment, vitreous haemorrhage, inflammation and cancer. Early diagnosis and referral to an eye care professional, such as an ophthalmologist or optometrist, enables a comprehensive examination using specialised cameras and ultrasound techniques followed by timely and appropriate treatment and prevention of blindness. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Kwok: None. Professor Chang has received consultation fees from Alcon, Apellis, Bayer, Novartis, Roche and Zeiss; honoraria from Apellis, Bayer and Roche. He is Secretary General for the Asia-Pacific Vitreo-retina Society, Deputy Secretary General of the Asia-Pacific Academy of Ophthalmology; and Chair and President of the Sydney Eye Hospital Foundation.

References

1. Salmon JF. Kanski’s clinical ophthalmology: a systematic approach. 9th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2020.

2. Holekamp NM. The vitreous gel: more than meets the eye. Am J Ophthalmol 2010; 149: 32-36.

3. Johnson MW. Posterior vitreous detachment: evolution and complications of its early stages. Am J Ophthalmol 2010; 149: 371-382 e1.

4. Bond-Taylor M, Jakobsson G, Zetterberg M. Posterior vitreous detachment - prevalence of and risk factors for retinal tears. Clin Ophthalmol 2017; 11: 1689-1695.

5. Jindachomthong KK, Cabral H, Subramanian ML, et al. Incidence and risk factors for delayed retinal tears after an acute, symptomatic posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmol Retina 2023; 7: 318-324.

6. Sagoo MS, Mehta H, Swampillai AJ, et al. Primary intraocular lymphoma. Surv Ophthalmol 2014; 59: 503-516.

7. Khoshnevis M, Rosen S, Sebag J. Asteroid hyalosis-a comprehensive review. Surv Ophthalmol 2019; 64: 452-462.

8. Mitchell P, Wang MY, Wang JJ. Asteroid hyalosis in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2003; 10: 331-335.

9. Fawzi AA, Vo B, Kriwanek R, et al. Asteroid hyalosis in an autopsy population: The University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) experience. Arch Ophthalmol 2005; 123: 486-490.

10. Nunes GM, Ludwig GD, Gemelli H, Zanotele M, Serracarbassa PD. Long-term evaluation of the efficacy and safety of Nd:YAG laser vitreolysis for symptomatic vitreous foaters. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2022; S0004-27492022005010216.

11. Delaney YM, Oyinloye A, Benjamin L. Nd:YAG vitreolysis and pars plana vitrectomy: surgical treatment for vitreous floaters. Eye (Lond) 2002; 16: 21-26.

12. Vukicevic M, Fitzmaurice K. Butterflies and black lacy patterns: the prevalence and characteristics of Charles Bonnet hallucinations in an Australian population. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008; 36: 659-665.

13. Paulig M, Mentrup H. Charles Bonnet’s syndrome: complete remission of complex visual hallucinations treated by gabapentin. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001; 70: 813-814.

14. Coletti Moja M, Milano E, Gasverde S, Gianelli M, Giordana MT. Olanzapine therapy in hallucinatory visions related to Bonnet syndrome. Neurol Sci 2005; 26: 168-170.

15. Balikov DA, Zhou Y, Miller JML. A telephone triage system for patients calling with symptoms of a posterior vitreous detachment. Ophthalmol Retina 2023; 7: 516-526.