Sudden leg weakness. Where is the problem? What is the cause?

Weakness in the legs of sudden onset requires urgent assessment and management. It is important to recognise that the actual onset of weakness may have preceded the patient’s awareness or acknowledgement, for up to weeks at a time. Careful history-taking and examination will distinguish an apparent sudden weakness (over days or weeks) from an actual sudden weakness (over minutes to hours), requiring emergent referral and management. This article provides GPs with an approach to sudden leg weakness.

- ‘Sudden’ weakness can be interpreted to mean weakness that becomes obvious over seconds, hours, days or weeks.

- Important diagnostic clues, such as localised spinal tenderness or an extensor plantar response, can be revealed during a brief physical examination. A thorough neurological examination will also evaluate the appearance, tone, power and sensation of the face, neck, trunk and arms, as well as the legs.

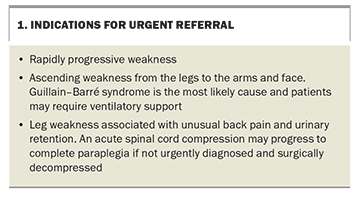

- Indications for urgent referral include rapid progression of weakness that is ascending from the legs to the arms and face, or leg weakness with back pain and urinary retention.

- An acute lesion of the spinal cord may be accompanied by ‘spinal shock’ and may obscure the distinction between an upper and a lower motor neuron lesion.

- Common causes of sudden leg weakness include drop attacks, the Guillain–Barré syndrome and nontraumatic spinal cord compression due to metastatic tumour or an epidural abscess.

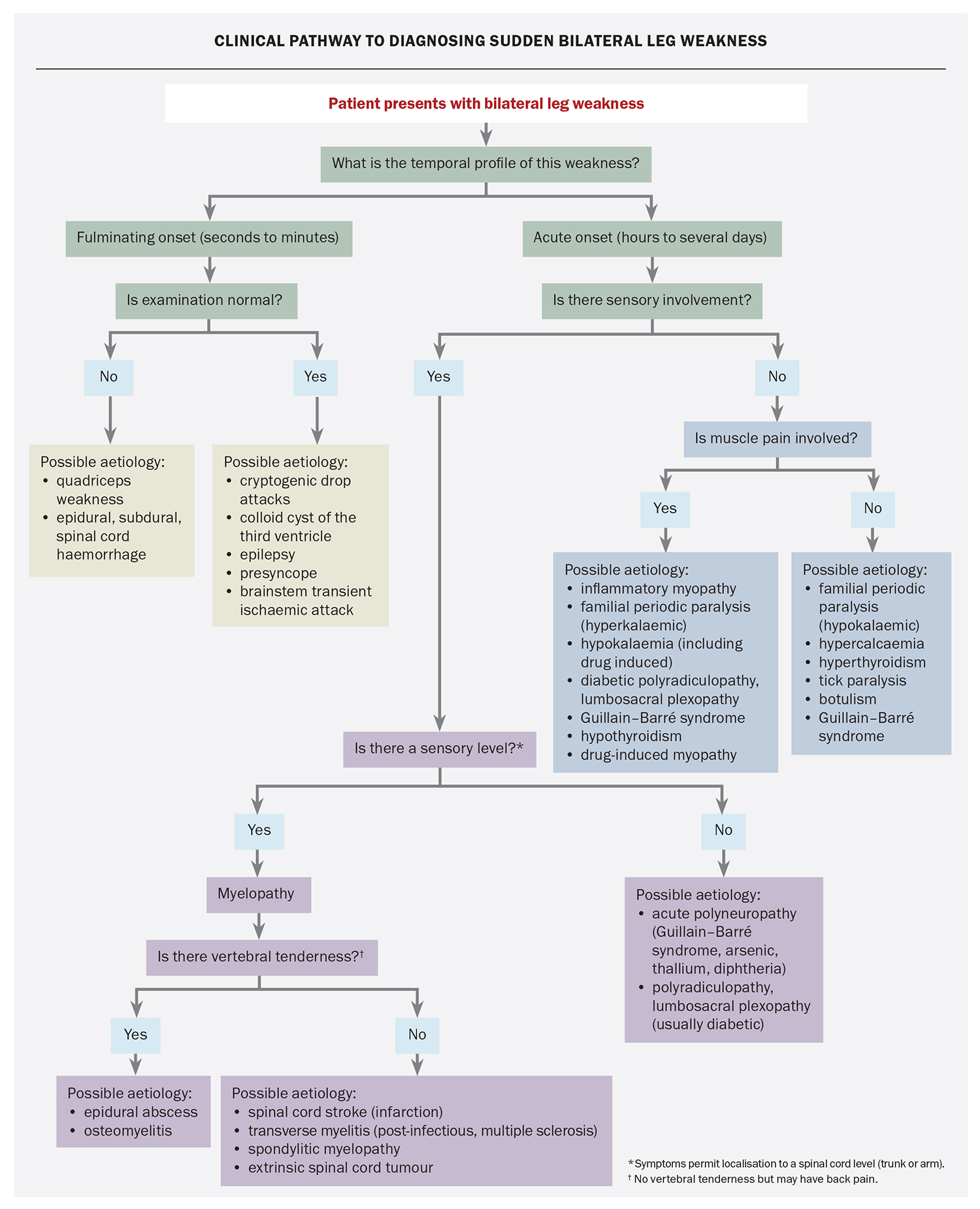

Neurological diagnoses are informed by identification of the precise location and aetiology of the underlying cause. GPs will have a working knowledge of the nervous system’s gross anatomical structures and physiology, as well as familiarity with common patterns of disease and their presenting features. In many cases, taking a careful history and performing targeted physical examination are sufficient for formulating an accurate diagnosis and developing a management plan (Flowchart). Initial investigations should not delay an emergent neurological referral, if indicated, such as with acute spinal cord compression requiring prompt neurosurgical decompression (Box 1). Other causes of acute ascending paralysis, such as with postinfectious neuropathy or electrolyte disturbance (e.g. hypokalaemia), require cause-specific interventions.

History

The presenting complaint

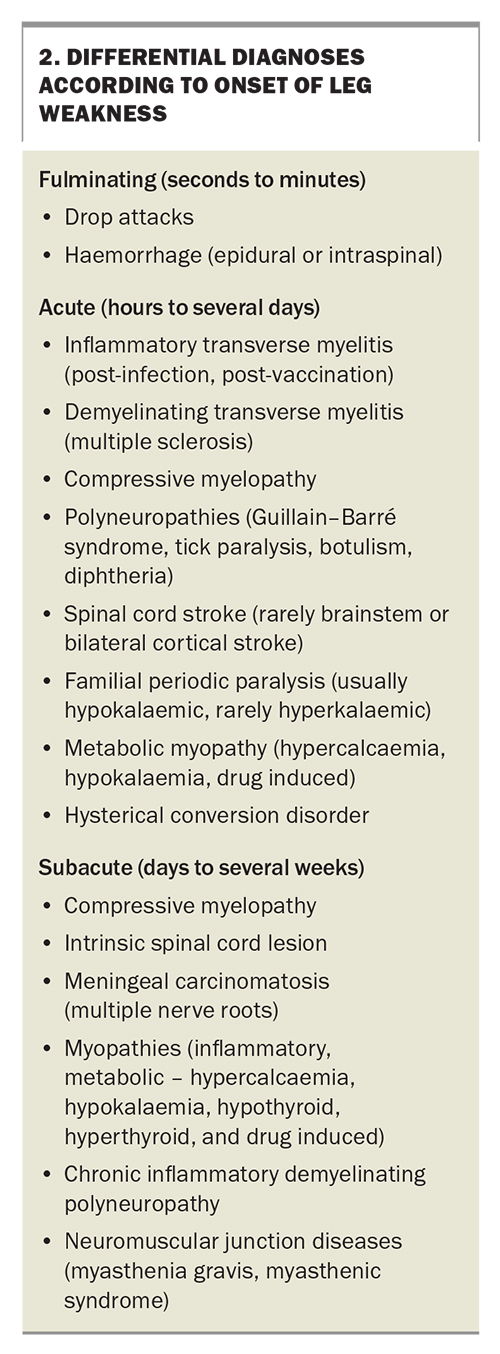

- What is the temporal profile of this weakness? Has it occurred over seconds to minutes, over hours to a day or two, or progressed over weeks? (Box 2)

- How and when has the weakness affected walking or running, going up and down stairs and getting up from a squatting position or chair?

- Has there been a previous episode of similar weakness?

- Is the weakness symmetrical? Did it begin in one or both legs?

- Is there any associated sensory disturbance or ‘level’? Such information can provide clues as to the location of the lesion.

- Is there back or leg pain? Local back pain may indicate infection or compression; however, back pain can also occur with transverse myelitis, Guillain–Barré syndrome, and diabetic radiculopathy or plexopathy.

- Is there any associated bladder or bowel dysfunction?

- Does neck flexion cause weakness or tingling in the legs?

- Is the problem stable, progressing or improving?

Past medical history

Vaccinations and associated illnesses, such as recent infections, vascular disease, malignancy and collagen vascular disease, can be relevant. A comprehensive systems review can identify symptoms of such conditions.

Medication history

Previous use or misuse of neurotoxic medications (e.g. chloroquine, colchicine, cytotoxic agents), myotoxic substances (e.g. heroin, alcohol) or heparin may contribute to sudden leg weakness. Similarly, exposure to chemical toxins, such as arsenic, thallium and herbal cathartics containing podophyllin, may be relevant.

Family history

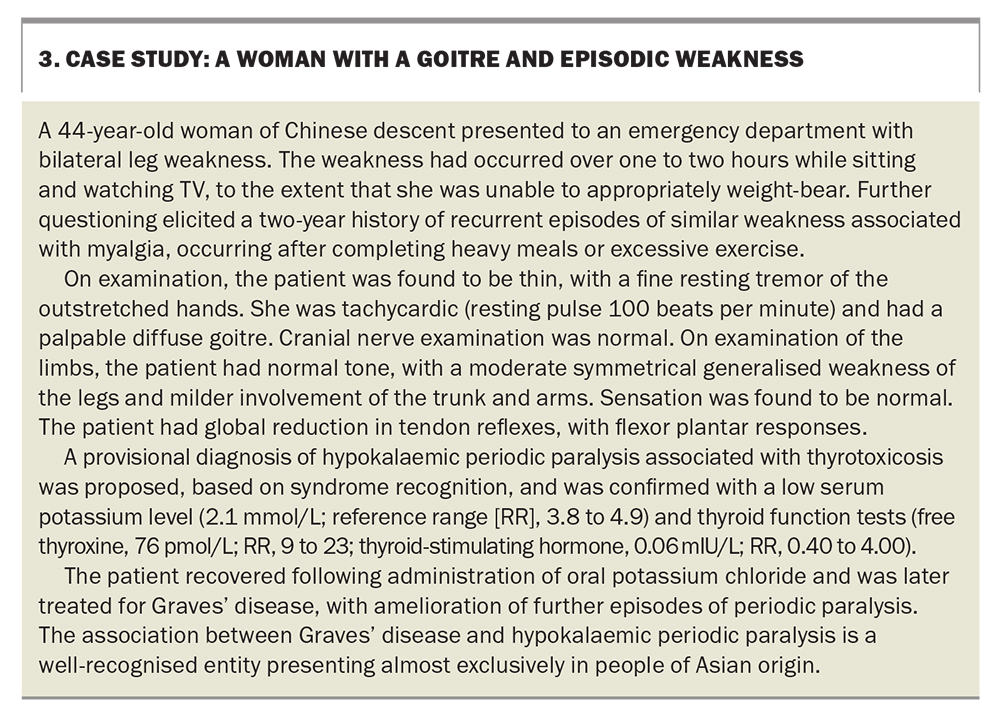

Although cases are not always familial, any family history of hypokalaemic periodic paralysis should be noted (Box 3).

Examination

General examination

An initial and brief general examination can yield important clues as to the diagnosis including:

- an irregular pulse, suggesting arrhythmia with associated risk of thromboembolism to the cerebral or spinal arteries

- stigmata of malignancy or collagen vascular disease

- localised spinal tenderness to percussion, suggesting an epidural abscess or local osteomyelitis

- a tick hidden in the posterior neck hairline.

Neurological examination

Specific neurological examination is guided by hypotheses generated from history-taking, with an emphasis on early examination of the legs.

Head and neck

- Leg paraesthesia or weakness on neck flexion can indicate cervical cord demyelination or canal stenosis (and spinal cord compression).

- Weakness of the face is present in 50% of Guillain–Barré syndrome patients during the disease course and may be evident on presentation, so test carefully for facial muscle weakness (especially eye and lip closure power).

- Abnormal eye movement or evolving ophthalmoplegia may point to Guillain–Barré syndrome or a multifocal central nervous system process, such as multiple sclerosis.

- Tongue movement and power may be weak in Guillain–Barré syndrome.

Trunk and upper limbs

- In examining the trunk, note whether superficial abdominal reflexes are present or absent, and test for abdominal muscle weakness on attempting to sit from lying in the supine position. A change to light touch or pinprick sensation may localise pathology to a thoracic spinal cord level.

- Signs of increased muscle tone, weakness, reflex or sensory abnormality in the arms can point to a cervical level or suggest a more generalised neuropathy.

Lower limbs

- Examine light touch, pinprick, position and vibration sensation. Include examination of the buttocks and perianal area, as well as the trunk. If abnormal, determine a sensory level, where possible.

- Identify any pattern to the weakness, such as with a proximal myopathy with graded distal to proximal weakness; flexor more than extensor muscle weakness of an upper motor neuron disorder; the reduced reflexes of a polyneuropathy; or the fatiguable weakness of a neuromuscular junction disease. In a patient with variable weakness against resistance and normal reflexes, consider hysterical conversion disorder.

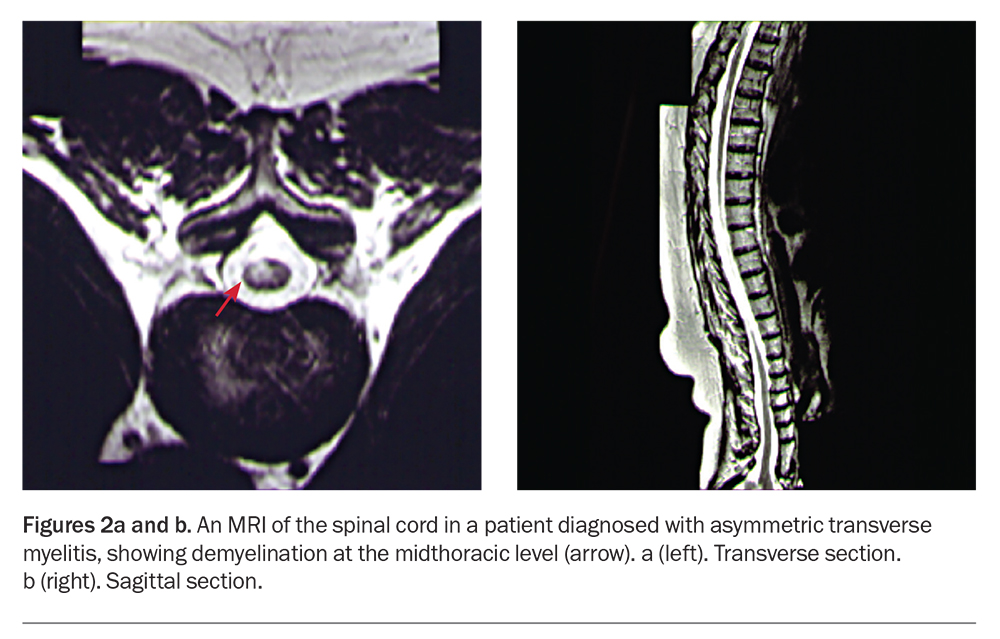

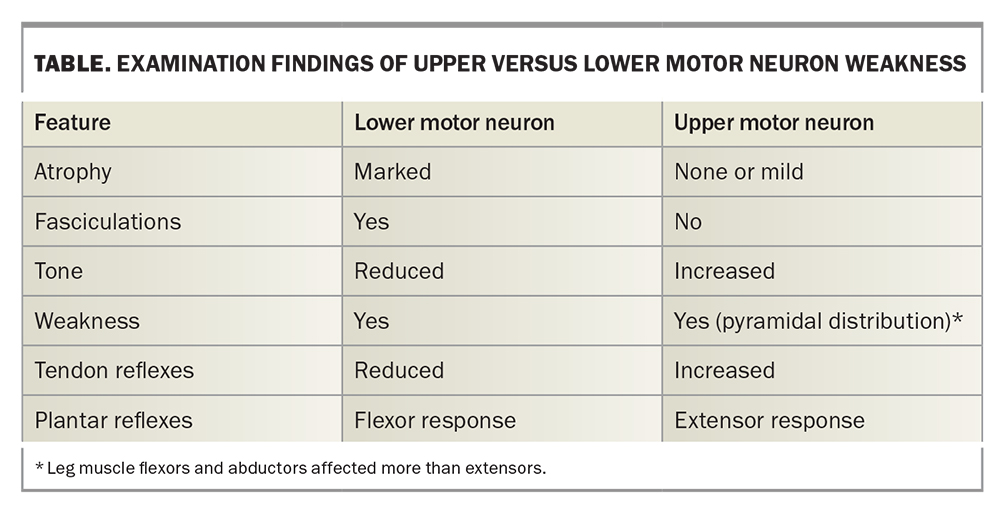

- Examine for upper or lower motor neuron signs (Table).

- Consider spinal shock (see below).

Investigations

Imaging

Plain x-rays

Plain x-rays of the spine may reveal a destructive bony lesion or severe degenerative spinal disease, but otherwise have little benefit in the investigation of sudden leg weakness.

Computed tomography

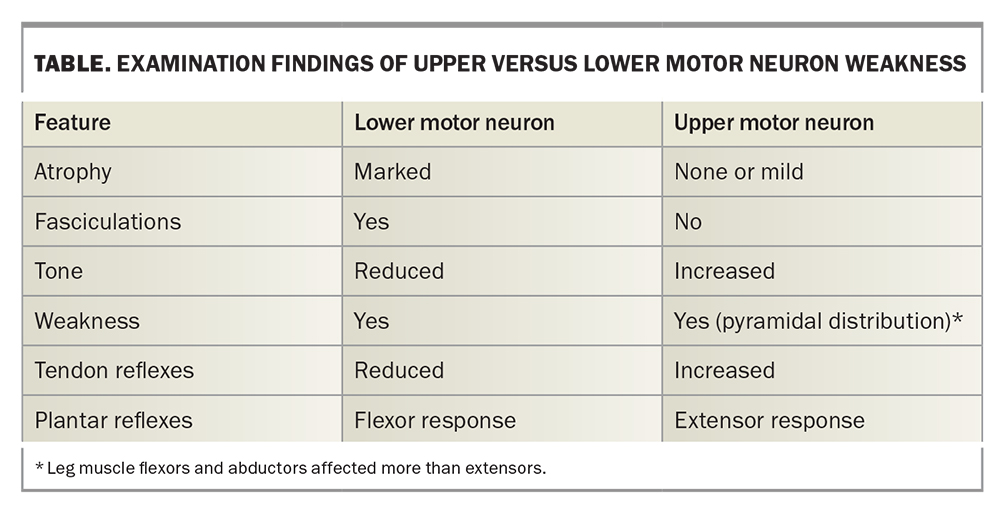

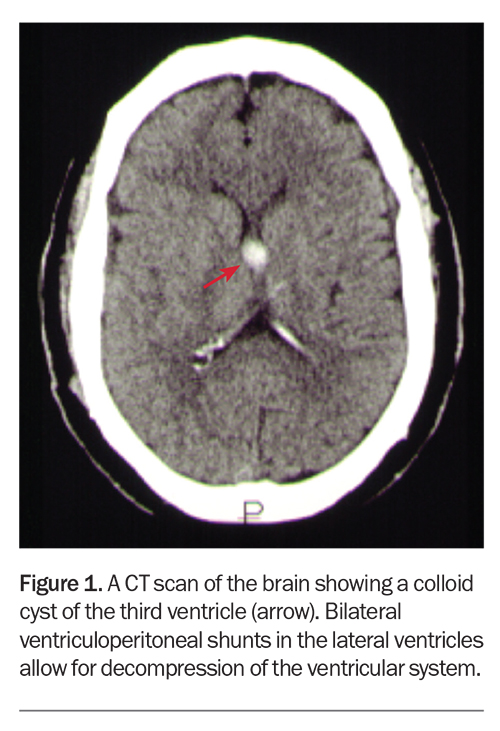

In clinical practice, CT is easier to access than MRI in investigating patients with a suspected spinal cord lesion. Figure 1 shows a colloid cyst of the third ventricle, which can be associated with sudden bilateral leg weakness.

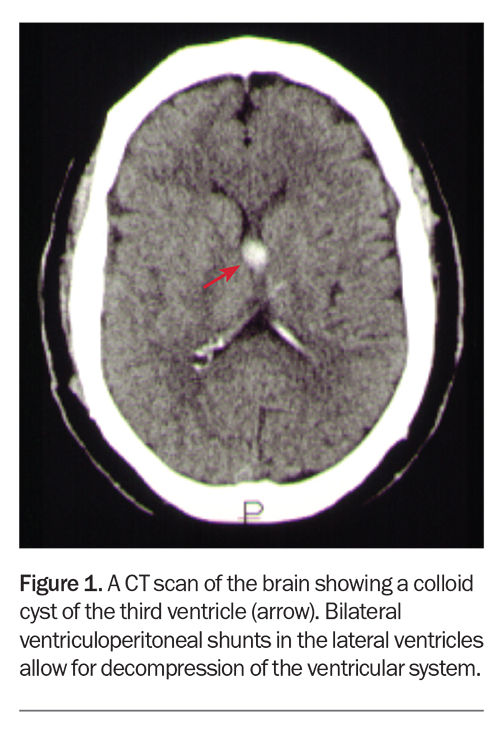

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI has superior resolution to CT scans and can display the spinal cord in both transverse and sagittal planes. MRI can also detect parenchymal spinal cord disease and extramedullary infection or haemorrhage. Figures 2a and b show demyelination of the thoracic spinal cord in the transverse and sagittal section, respectively.

Neurophysiology

Nerve conduction studies

Nerve conduction studies may be urgently arranged to assist in the diagnosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome. The usual findings are significant slowing of conduction velocity and conduction block.

Electromyography

Electromyography may aid in the anatomical localisation of causative pathology to the level of the nerve root, plexus, peripheral nerve, neuromuscular junction or muscle.

Lumbar puncture

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis is required if acute spinal subarachnoid haemorrhage or infection is suspected. Lumbar puncture is desirable, but not necessary, for the diagnosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome, and the characteristic rise in protein levels may not be seen early in the disease.

Common diagnoses

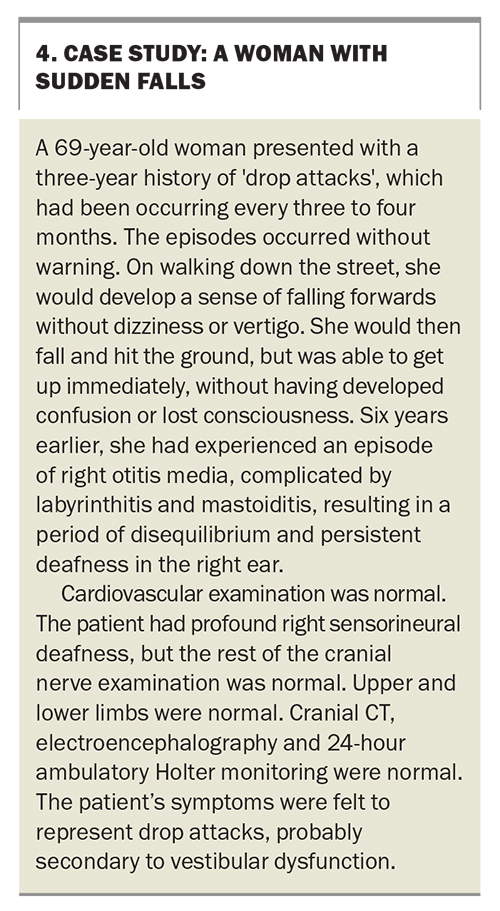

Drop attacks

A drop attack is an unexpected fall with no obvious loss of consciousness (Box 4). The affected patient can usually rise immediately afterwards, but there is always a possibility of injury. The associations and causes of drop attack include epilepsy, vertebrobasilar insufficiency, quadriceps weakness, presyncope, multiple sclerosis, whiplash and midline cerebral lesions with acute intermittent hydrocephalus, such as a colloid cyst of the third ventricle (Figure 1). In clinical practice, most cases of drop attack occur in women who are otherwise healthy and have no apparent cause (‘cryptogenic drop attacks’). The pathophysiology may relate to differences in postural control mechanisms between women and men.

Guillain–Barré syndrome

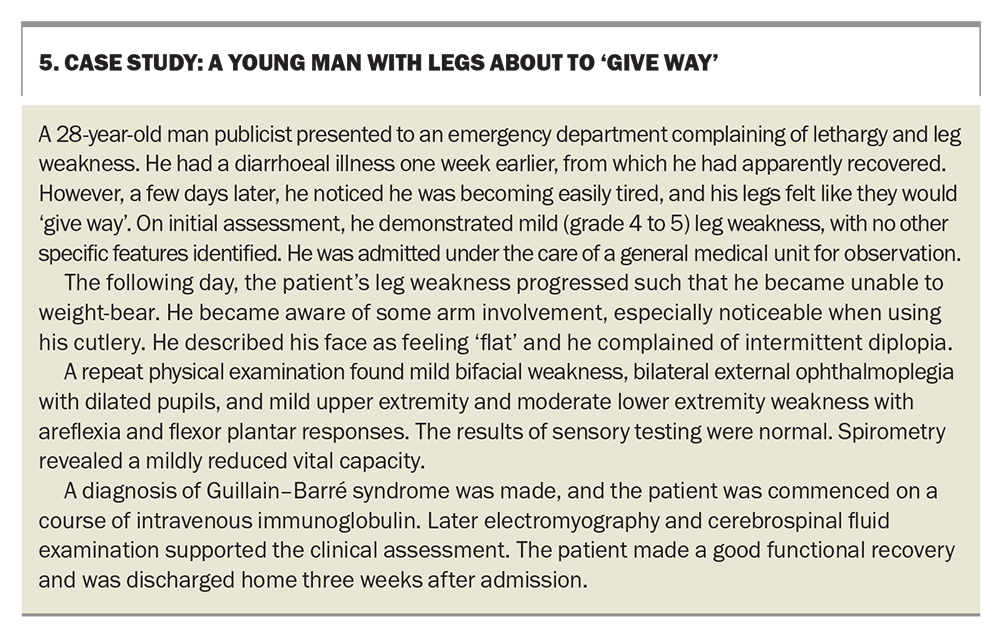

Guillain–Barré syndrome is the most common form of acute polyneuropathy. Early diagnosis is important because of the potential for rapid deterioration and need for ventilatory support. For most patients, the initial symptoms are muscle weakness (up to 99%), paraesthesia (70%) and myalgia (30%). Weakness is noticed first in the legs (85%), arms (10%) or face (5%), and a bacterial or viral infection may precede symptom onset (Box 5). The differential diagnoses of Guillain–Barré syndrome include botulism, tick paralysis (in eastern Australia), severe acute hypokalaemia, meningeal carcinomatosis and acute transverse myelitis with ascending weakness and sensory disturbance.

Most cases of Guillain–Barré syndrome will improve with intravenous immunoglobulin or plasma exchange. Supportive management includes prevention of the complications of immobility and, in the event of respiratory impairment or failure, admission to an intensive care unit. About 15 to 25% of patients with Guillain–Barré syndrome experience persistent functional deficit and the mortality rate is 5 to 10%.

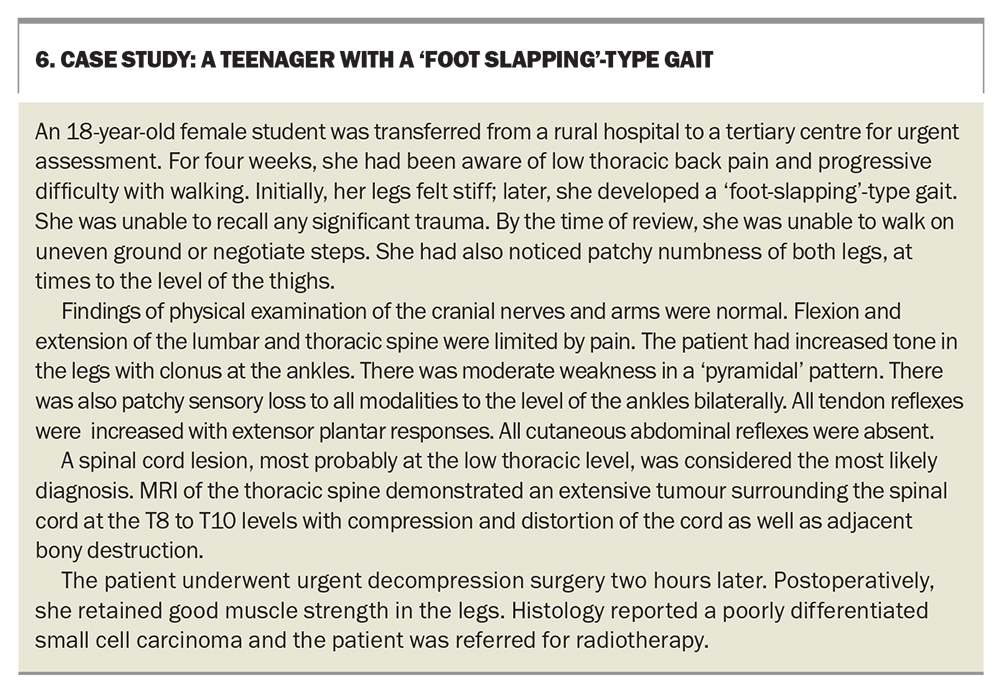

Nontraumatic spinal cord compression

The clinical features of spinal cord compression depend on its location and the speed of its onset. In acute lesions, the rapid loss of motor power is associated with reduced muscle tone, variable weakness and sensory loss. Bladder dysfunction tends to occur later, except in acute cauda equina compression where it is an early feature. Spinal pain mostly predates or accompanies the onset of neurological symptoms in spinal cord compression.

The two most common aetiologies for acute nontraumatic spinal cord compression are metastatic tumour and infection (epidural abscess). Their main differential diagnoses are transverse myelitis and spinal stroke. Other rare causes of acute cord compression include epidural and subdural haemorrhage.

Imaging and surgical treatment must be carried out urgently if neurological function is to be preserved. Spinal MRI is the definitive investigation of choice, giving morphological information regarding the site of compression and the presence of tumour or infection (Box 6). If MRI is not available, myelography combined with CT scanning provides similar information, but carries a small risk of neurological deterioration. The timeliness of investigation and management can significantly reduce morbidity in patients with acute spinal cord compression.

Spinal shock

An acute lesion of the spinal cord may be accompanied by ‘spinal shock’, which may obscure the signs distinguishing upper and lower motor neuron lesions (Table). When the spinal cord is suddenly and severely damaged (such as by infarction, haemorrhage, sudden compression or inflammation), cord function and reflexes below the affected level become depressed or lost. Recovery occurs gradually over weeks; first, of reflexive function with extensor plantar responses (Babinski’s sign), and then of muscle tone and tendon reflexes. Care must be taken not to misinterpret flaccid paraplegia as being due to a hysterical conversion disorder.

Conclusion

Sudden weakness of the legs may develop over seconds, hours, days or weeks, and urgent assessment is always required. History-taking should acquire information regarding the patient’s presenting complaint, past medical conditions, current medications and familial illnesses. General examination can yield important diagnostic clues, and focused neurological assessment should be guided by factors in the patient’s history, with an emphasis on early examination of the patient’s legs. Rapidly evolving weakness of the legs, unusual back pain and bladder dysfunction requires exclusion of acute spinal cord compression, and should indicate emergent referral for accurate diagnosis, early investigation and prompt neurosurgical decompression to significantly reduce adverse health outcomes. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

Further reading

1. Johnston RA. The management of acute spinal cord compression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1993; 56: 1046-1054.

2. Meissne I, Wiebers DO, Swanson JW, O’Fallon M. The natural history of drop attacks. Neurology 1988; 36: 1029-1034.

3. Grattan-Smith PJ, Morris JG, Johnston HM, et al. Clinical and neurophysiological features of tick paralysis. Brain 1997; 120: 1975-1987.

4. McLeod JG. Guillain–Barré syndrome: a GP’s guide to diagnosis and management. Mod Med Aust 1995; 38(10): 30-34.

5. Al Deeb SM, Yaqub BA, Bruyn GW, Biary NM. Acute transverse myelitis. A localised form of postinfectious encephalomyelitis. Brain 1997; 120: 1115-1122.

6. Ropper AH. The Guillain–Barré syndrome. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 1130-1136.