Cosmetic sclerotherapy for leg and other veins

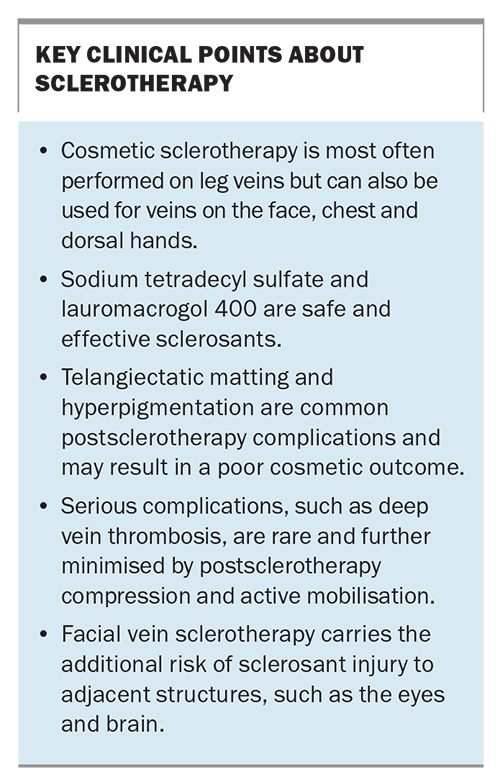

Cosmetic sclerotherapy is most often used to ablate leg veins and can reduce their prominence. It can also be used to treat veins on the chest, hands and face. Common side effects include haemosiderin pigmentation (staining) and formation of fine compensatory vessels (matting), which are usually transient. Patients should be fully informed about the procedure and realistic expectations of its outcome.

Sclerotherapy is the technique of injecting sclerosants to cause chemical ablation of veins. Cosmetic sclerotherapy focuses predominantly on veins in the lower limbs but can also be applied to other sites, such as the face, upper limbs and torso.

Most patients who seek cosmetic sclerotherapy are women with concerns about the appearance of veins in the lower limbs. However, it is estimated that up to one-third or more of patients who present with cosmetic concerns about leg veins have underlying superficial venous insufficiency that requires concurrent management for a satisfactory cosmetic outcome.1 Patients with suspected venous insufficiency require additional ultrasound investigation and definitive treatment such as ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy, if clinically indicated.2 Sclerotherapy remains the benchmark for treating telangiectatic and reticular leg veins of the lower limb, with or without concurrent venous insufficiency. Sclerotherapy is indicated for blue-green reticular veins and purple-red telangiectasias of the lower limb (Figure 1). Vessel diameters are typically less than 3 mm for reticular veins and less than 1 mm for telangiectasias.

Approaches to sclerotherapy

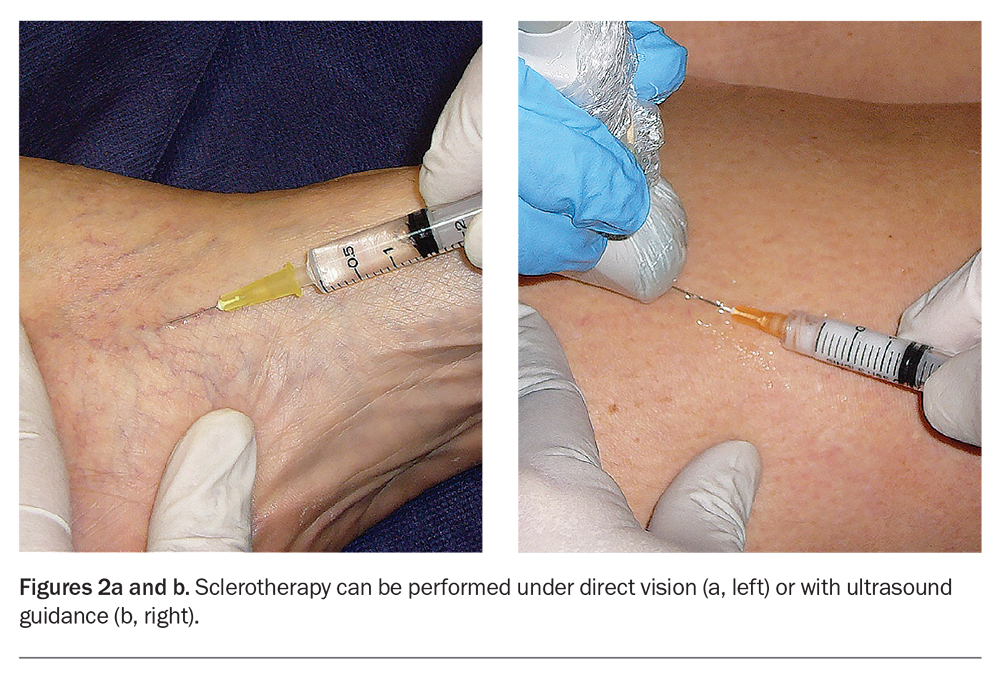

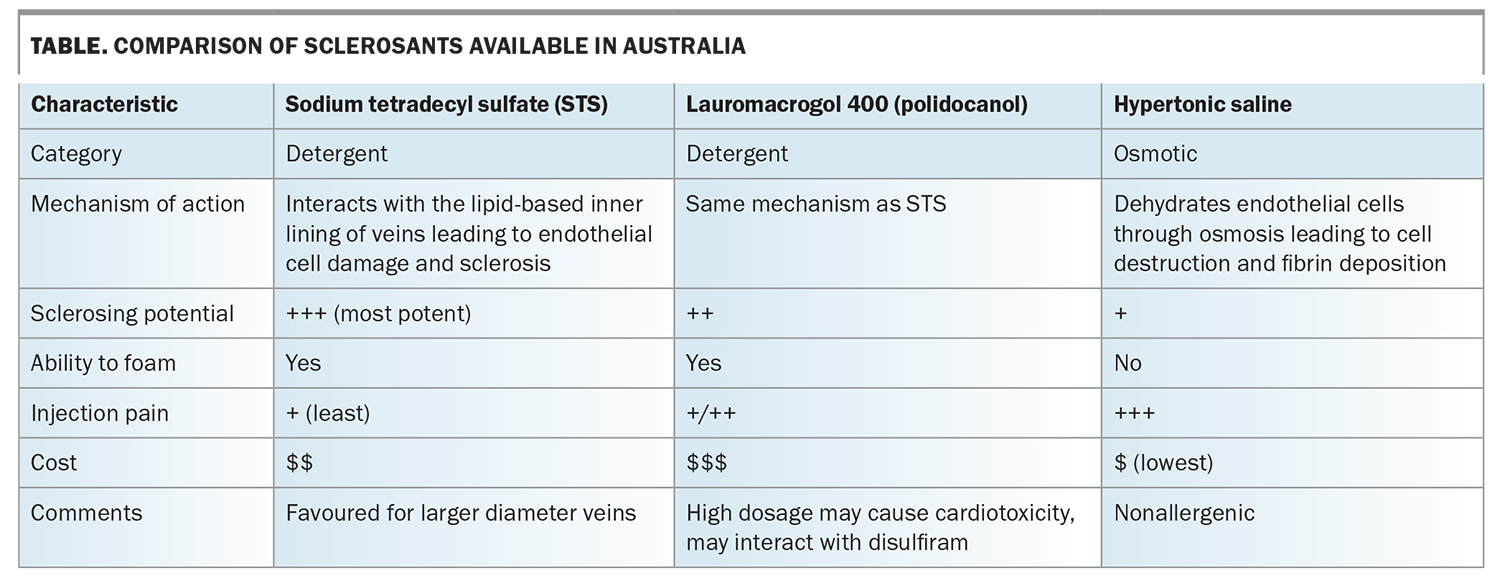

Sclerotherapy can be carried out under direct vision or ultrasound guidance (Figures 2a and b). In direct-vision sclerotherapy, visible veins are injected with sclerosants that disrupt the vascular endothelial lining, resulting in vein sclerosis or fibrosis that is subsequently absorbed by the body. Commercially available sclerosants include hypertonic saline, sodium tetradecyl sulfate and lauromacrogol 400 (commonly known as polidocanol). Characteristics of these sclerosants are compared in the Table.

Direct-vision sclerotherapy is the mainstay for treating cosmetic leg veins that are visible by clinical inspection. The limitation of direct-vision sclerotherapy is its inability to adequately treat incompetent leg veins that are not clinically visible. Up to one third or more of seemingly superficial cosmetic leg veins may have ‘hidden’ incompetent or refluxing veins that would be missed without the benefit of Doppler or duplex ultrasound investigations.1,3

Postsclerotherapy care and progression

After sclerotherapy, compression stockings are routinely applied for one to three weeks to enhance the sclerosing process and minimise potential sclerotherapy-related complications. Patients should also take daily 30-minute walks during the first one to two weeks.

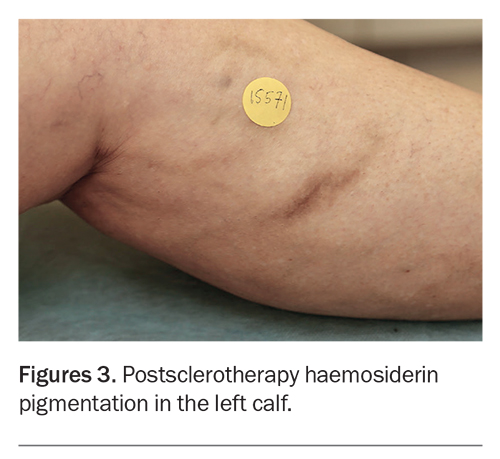

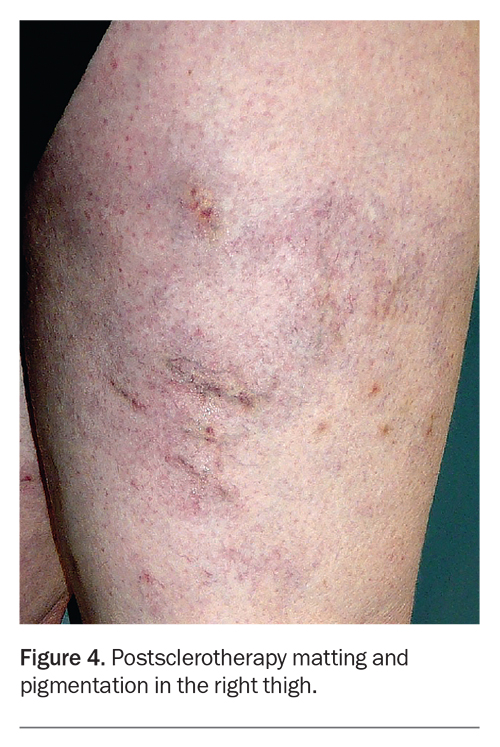

The treated veins often look worse before their appearance improves. Injection-associated bruising settles in two weeks, and there is usually some darkening of the veins caused by retained blood within the treated vessel. The haemosiderin (iron) content of blood can stain adjacent tissue to produce brown hyperpigmentation (haemosiderin staining), which can persist for several months (Figure 3).4,5 Transient matting (formation of clusters of fine compensatory vessels near the treated vein) may also occur but is usually self-limiting (Figure 4). The extent, severity and persistence of hyperpigmentation and matting can be minimised by close adherence to the postsclerotherapy requirements to wear compression stockings and take daily walks during the first one to two weeks.

In the first month, the worsened appearance of the treated legs is mostly covered by the compression stockings. In the second month, when the leg is out of compression, patients may notice ‘hot spots’ or benign segmental phlebitis along the course of the treated vein. This usually settles on treatment with short-term compression and oral anti-inflammatory medication, or release of any segmental trapped blood within the treated vein. From the third month onwards, the sclerosed vein progressively undergoes resorption and clears with time. Telangiectasias and reticular veins clear within two to three months. Varicose veins may take up to six months or longer to resolve fully.

Although not complications as such, the natural postsclerotherapy changes are a common source of concern for patients and trigger for complaints about unsatisfactory outcomes, especially when patients have not been fully informed of what to expect. Unless specifically told, patients typically expect the veins to resolve within a few days or weeks, rather than months. Patients who have undergone previous vascular laser treatment for facial capillaries may erroneously draw on that experience, where laser-treated capillaries clear instantly or within days, and expect the same for leg vein sclerotherapy. In addition, videos on social media often show telangiectasias instantly clearing during sclerotherapy when blood is displaced by colourless sclerosant, without showing the reappearance of the vessels shortly afterwards when blood returns and displaces the sclerosant.

Patients may also expect complete and permanent eradication of leg veins instead of their reduction. Invariably, maintenance treatment is needed as there may be recurrence or development of new veins with time as a function of genetics, gravity, obesity and lifestyle factors.

Sclerotherapy complications

As described above, the most common unwanted side effects of sclerotherapy are hyperpigmentation and telangiectatic matting. Up to one-third of patients experience mild hyperpigmentation or matting. These are often temporary and resolve with time, usually over three to six months. In severe cases, staining may persist up to one year and in some cases, matting may persist long-term. Mild degrees of phlebitis may occur during convalescence, especially after treatment of larger and more severe varicose veins. Rarely, a minority of patients will experience a poor outcome, with persistent matting or hyperpigmentation, where the appearance of the legs is worse after sclerotherapy.

Rare complications of sclerotherapy include deep vein thrombosis (DVT), prolonged ankle oedema, skin ulceration (Figure 5) and allergies. DVTs are exceedingly uncommon because of the ambulatory nature of the procedure. In addition, recent in vitro studies showed that the sclerosants sodium tetradecyl sulfate and polidocanol are modestly anticoagulant at the concentrations used in varicose vein treatment.6 Minor thrombosis of calf veins is low risk and may be managed with compression and NSAIDs. More proximal thrombosis affecting the popliteal vein and above requires anticoagulation therapy.

Foam sclerotherapy, in which a liquid sclerosant is mixed with gas, is often used to treat varicose veins and smaller venules. Complications of foam sclerotherapy are gas embolism-related, and include transient visual disturbance similar to visual migraine, with or without headache. Rarely, patients with a significantly patent foramen ovale, which permits crossover of gas from the right to left cardiac chambers, may experience gas embolism in the arterial system resulting in a transient ischaemic attack or even stroke.4 It has been estimated that up to 25% of the population may have some form of patent foramen ovale.7 However, the incidence of cerebrovascular complications has been extremely low and can be further mitigated by using carbon dioxide gas and keeping the foam to a low volume (typically less than 20 mL or even lower for less experienced injectors).4

In discussing the procedure with patients, allow adequate time for questions and clarifications. It is also necessary to reframe relevant risks and complications in the light of specific patient concerns.

Laser therapy versus sclerotherapy

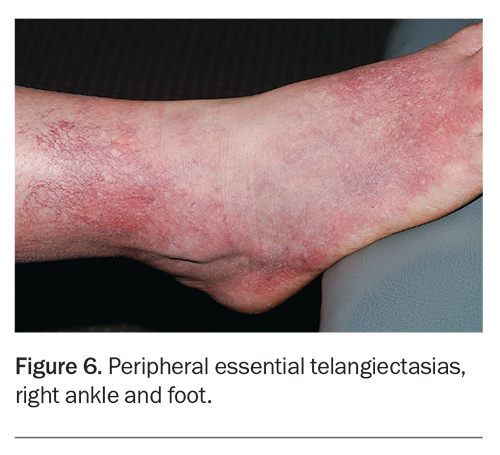

In our experience, treatment with external beam vascular lasers is seldom a suitable alternative to sclerotherapy for most patients wanting treatment of leg veins, especially larger diameter telangiectasias and reticular veins. Vascular lasers cannot consistently ablate incompetent reticular veins feeding surface telangiectasias without an increased risk of burns to the surrounding skin. Lasers can deliver comparable results to sclerotherapy in selected patients with very small calibre vessels without venous insufficiency.8 However, laser therapy tends to be slower to perform and associated with more pain.8 It also comes with mandatory laser safety requirements. Lasers are nevertheless preferred when treating postsclerotherapy angiogenesis (matting), peripheral essential telangiectasias (Figure 6), and incidental telangiectasias without venous incompetence.

However, treatment with lasers or light devices is preferred to sclerotherapy for telangiectasias on the torso and face, as these veins are not usually associated with underlying venous insufficiency. Also, vascular lasers play a role when there are site-specific risks, such as the potential for sclerosant-associated brain and eye injury with sclerotherapy of periorbital veins. Patients with needle phobia may often also insist on the laser option for treatment of leg veins despite the suboptimal outcome.

Contraindications to sclerotherapy

The main absolute contraindications to sclerotherapy are previous anaphylaxis to the sclerosant and acute DVT. Relative contraindications or special precautions include deep venous obstruction, patient inability to mobilise, poor tolerance of compression stockings, documented thrombophilia, peripheral vascular disease (which predisposes to poor tolerance to compression), pregnancy, breastfeeding, use of the oral contraceptive pill or menopausal hormone therapy in conjunction with other prothrombotic risk factors, poor general health, recent long-distance travel, hospitalisation or enforced bed rest. Many of these contraindications relate to factors that increase DVT risk, either directly or indirectly by interfering with post-treatment compression and mobilisation.

Sclerotherapy for non-leg veins

Patients with cosmetic concerns about leg veins may have coexisting incompetent superficial veins. However, concerns about veins in other parts of the body are entirely cosmetic in nature, and typically involve veins on the dorsum of the hands, on the torso or face. The longer wavelength 1064 nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) vascular laser has a role in the treatment of non-leg veins, either as monotherapy or in combination with sclerotherapy.

Dorsal hand veins

The hands are an important aesthetic feature that can reveal ageing through surface pigmentary changes, skin thinning and ectatic veins (Figures 7a and b). Patients may present asking to reduce the prominence of these veins. Fillers can be considered as a medium-term (six to 12 months) option to reduce the prominence of dorsal hand veins. Sclerotherapy can permanently reduce or eliminate vein calibre. Fillers and sclerotherapy can also be combined for optimum long-term results.9 In practice, filler correction can be offered first as it has fewer potential adverse effects. If ectatic dorsal hand veins do not respond fully to filler injections alone then combining injections with sclerotherapy can improve results.

All potential sclerotherapy-related complications for leg veins can also occur for dorsal hand veins. However, matting (neoangiogenesis) and haemosiderin staining are far less common in the hands, whereas any sclerotherapy related thrombophlebitis tends to be more concerning, given the proximity to the heart and lungs. Eradicating dorsal hand veins will also hinder intravenous cannulation to the treated areas. For these reasons, upper limb cosmetic sclerotherapy should not extend beyond the wrist into the veins of the forearm.

Chest veins

Prominent chest and breast veins can be an issue for some patients after undergoing breast augmentation. In this setting, sclerotherapy is preferred over use of the long-wavelength vascular laser (1064 nm Nd:YAG), as the latter may damage the underlying breast implant.

All potential sclerotherapy-related complications can also occur after treatment of chest veins. As for dorsal hand veins, sclerotherapy of chest veins tends to be associated with a much lower incidence of matting and staining. However, the volume of sclerosant should be conservative because of the proximity to vital thoracic organs.

Facial veins

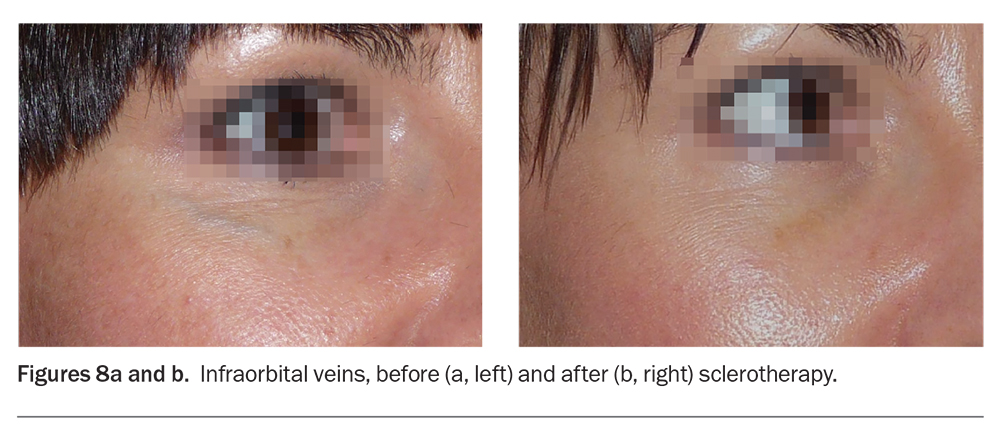

The periorbital, temple and forehead veins are the more frequently requested sites for sclerotherapy on the face. Prominent periorbital veins contribute to infraorbital shadows and the appearance of tiredness (Figures 8a and b). Patients often perceive prominent periorbital veins as a significant disfigurement and may actively seek treatment. Both sclerotherapy and vascular lasers can effectively treat facial veins.10,11 In our experience, a combination procedure comprising sclerotherapy immediately followed by vascular laser therapy may produce better results and require fewer treatment sessions.

Eye and brain injury due to retinal vein and cavernous sinus thrombosis, respectively, are possible after sclerotherapy. However, the literature indicates that these catastrophic complications are rare and that prominent periorbital veins can be safely and effectively treated with sclerotherapy and Nd:YAG laser, alone or in combination.10,11 There have been reports of blindness associated with sclerotherapy of facial vascular malformations and haemangiomas (associated with abnormal anatomy and requiring high dose sclerosants) but none with standard sclerotherapy to nonmalformed facial veins.12 There was a reported case of blindness from attempted forehead frontal vein sclerotherapy where the artery was cannulated instead of the vein.13

Given the catastrophic nature of potential sclerotherapy-induced thromboembolic injury to the eye and brain, patients must be fully informed and allowed enough time to consider the risks, with a minimum mandatory cooling-off period of seven days, or preferably longer. Sclerotherapy on facial sites should be performed only by experienced phlebologists.

Conclusion

Cosmetic sclerotherapy for leg veins is a commonly sought procedure. Cosmetic sclerotherapy is also performed on periorbital veins and veins of the chest and dorsum of the hands. Key clinical points about sclerotherapy are summarised in the Box. As the indications are cosmetic, a thorough informed consent process highlighting the risks and potential complications is mandatory, including understanding the natural progression of treated veins. Complications should be discussed in lay language framed around specific patient concerns, and both generic and site-specific adverse events should also be adequately addressed. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Lim has been on Technical Advisory Boards for NSW Department of Health; is Board Member for the Australasian College of Phlebology; and owns shares in EBOS Healthcare Australia. Dr Elvy, Dr Jenkins: None.

References

1. Robertson L, Evans C, Fowkes FG. Epidemiology of chronic venous disease. Phlebology 2008; 23: 103-111.

2. Elvy M, Jenkins D, Lim A. et al. Varicose veins – more than a cosmetic concern. Med Today 2023; 24(3): 53-59.

3. Thibault P, Bray A, Wlodarczyk J, et al. Cosmetic leg veins: evaluation using duplex venous imaging. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1990; 16: 612-618.

4. Cavezzi A, Parsi K. Complications of foam sclerotherapy. Phlebology 2012; 27 Suppl 1: 46-51.

5. Watson JJ, Mansour MA. Cosmetic sclerotherapy. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2017; 5: 437-445.

6. Parsi K, Exner T, Low J, et al. In vitro effects of detergent sclerosants on antithrombotic mechanisms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2009; 38: 220-228.

7. Kheiwa A, Hari P, Madabhushi P, et al. Patent foramen ovale and atrial septal defect. Echocardiography 2020; 37: 2172-2184.

8. Parlar B, Blazek C, Cazzaniga S, et al. Treatment of lower extremity telangiectasias in women by foam sclerotherapy vs. Nd:YAG laser: a prospective, comparative, randomized, open-label trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 549-554.

9. Lim A, Mulcahy A. Hand rejuvenation: combining dorsal veins foam sclerotherapy and calcium hydroxylapatite filler injections. Phlebology 2017; 32: 397-402.

10. Green D. Removal of periocular veins by sclerotherapy. Ophthalmology 2001; 108: 442-448.

11. Chen DL, Cohen JL. Treatment of periorbital veins with long-pulse Nd:YAG laser. J Drugs Dermatol 2015; 14: 1360-1362.

12. Colletti G, Deganello A, Bardazzi A, et al. Complications after treatment of head and neck venous malformations with sodium tetradecyl sulfate foam. J Craniofac Surg 2017; 28: e388-e392.

13. Arunakirinathan M, Walker RJE, Hassan N, et al. Blind-sided by cosmetic vein sclerotherapy: a case of ophthalmic arterial occlusion. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2019; 13: 185-188.