Varicose veins – more than a cosmetic concern

Varicose veins are a common venous disorder with a cosmetic dimension that often results in delayed treatment. Patients should be assessed and monitored for progression of associated venous conditions and intervention individualised according to the patient’s preference, history and venous pathology, and practitioner expertise. Currently available therapies tend to be nonsurgical and minimally invasive.

Varicose veins have a disease and cosmesis duality that is reflected in polarising attitudes among healthcare providers, ranging from ‘leave it alone’ to ‘get it stripped’. Over the past 50 years, varicose vein treatment has evolved from surgical stripping to nonsurgical alternatives, such as ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy, endovenous thermal ablation (EVTA; laser or radiofrequency) and cyanoacrylate (glue) closure (CAC).1 Consequently, the specialty domain has widened beyond vascular and general surgeons to include interventional radiologists, interventional dermatologists, GP-phlebologists and cosmetic practitioners, all practising under the discipline of phlebology – a specialty dedicated to venous and lymphatic disorders.

Varicose veins and venous insufficiency

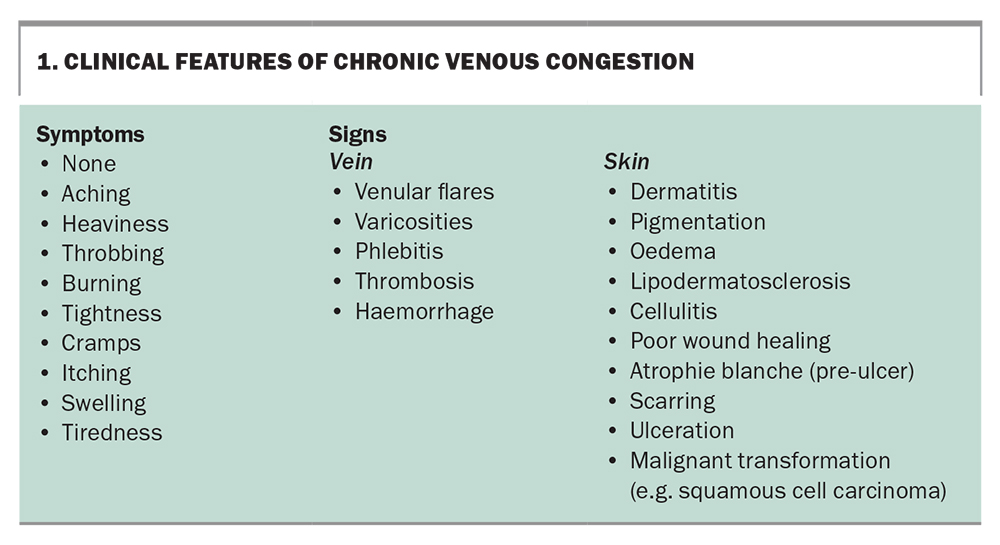

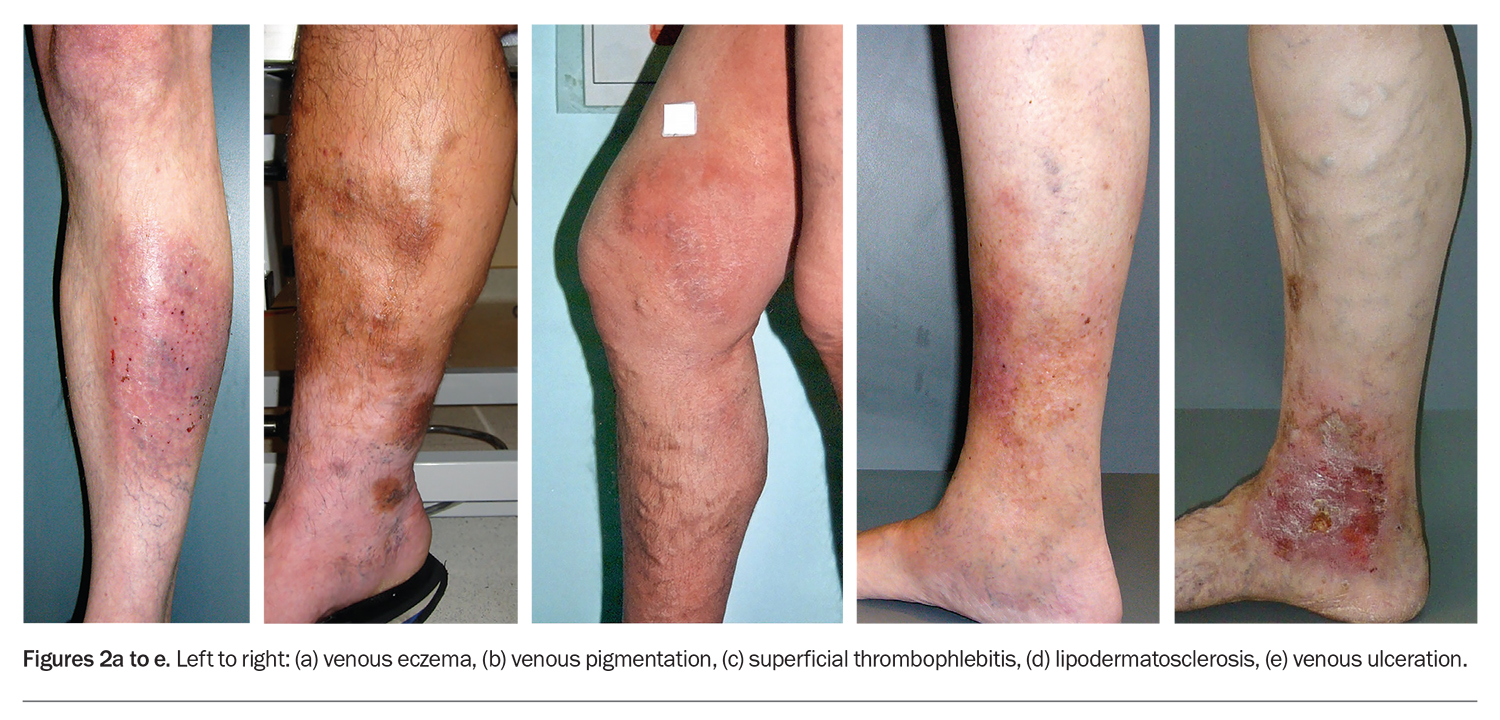

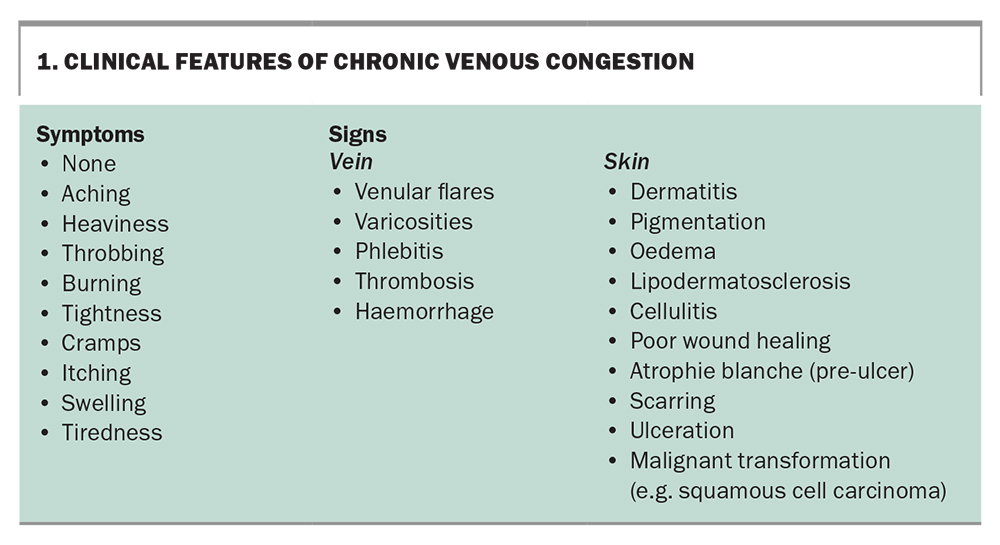

Up to 30% of adults may have some degree of venous insufficiency that can present as dilated, tortuous varicose veins draining into either the great or small saphenous venous systems of the lower limb (Figure 1).2 The term venous insufficiency is interchangeable with the terms venous incompetence, venous hypertension and venous congestion, and indicates elevated intravenous pressure that can lead to well-recognised skin and vein complications (Box 1 and Figure 2).3 The severity and extent of varicose veins progressively worsen with age, with contributory hereditary and lifestyle factors (e.g. body mass index above the normal range and a sedentary lifestyle).4 Varicose vein treatment can improve quality of life through symptom relief, reversing complications of chronic insufficiency and improvement in cosmesis.5

Minimally invasive therapies

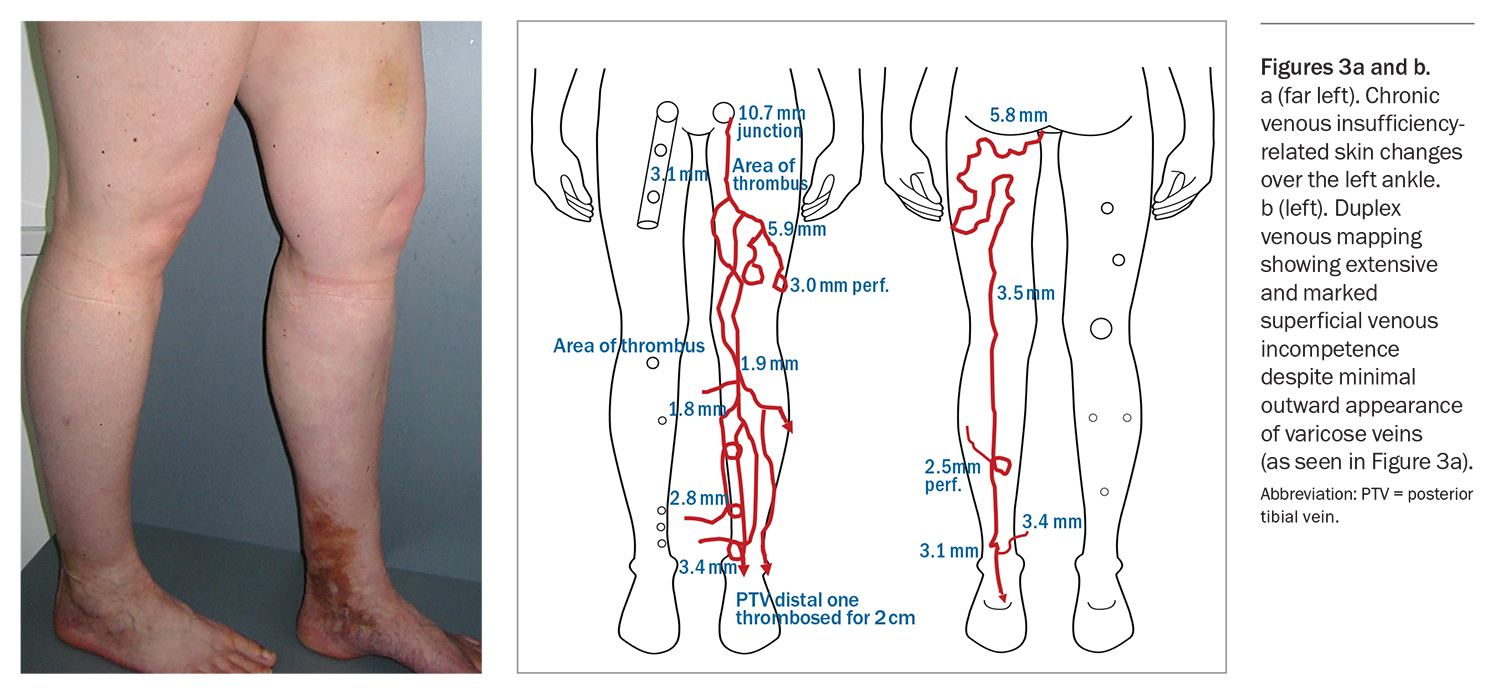

Varicose vein stripping, widely performed since the 1940s, has given way to ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy and EVTA in the millennium and, more recently, CAC. The hierarchy of treatment options centres around safe and effective minimally invasive procedures validated by systematic reviews and endorsed by consensus statements.1,6 Many of the minimally invasive options are made possible because of advancements in the resolution and capabilities of venous sonography. Duplex scans can visually identify superficial and deep venous reflux or incompetence, even when the varicose veins are not clinically obvious (Figure 3).

Colour duplex (Doppler and B-Mode) scans have replaced the more invasive venography for routine evaluation of lower-limb venous disease.7 Low-cost, portable point-of-care Doppler imaging devices have also arrived on the medical device market and are finding their way into wider clinical settings.

Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy

Ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) continues to be a versatile and popular modality for treating varicose veins, either as a stand-alone procedure or in combination with other modalities.8 UGFS is often combined with endovenous ablation for comprehensive treatment of lower-limb varicose veins. Additionally, UGFS is particularly useful for postsurgical recurrent varicose veins and treatment of venous malformations.9,10

Because of their detergent-like properties, the sclerosants (sodium tetradecyl sulphate or polidocanol) can be manually foamed from their liquid state via a two- or three-way tap. Foam microbubbles can reach the heart, lungs and brain (during leg vein treatment) and may cause transient headaches, visual disturbances and coughing.11 Rarely, strokes following treatment with UGFS have been reported, resulting from air embolism from a patent foramen ovale.11 To minimise excessive air embolism, the total foam volume per treatment session should be closely monitored.

Advantages

UGFS is an effective low-cost technique that can treat vessels of all sizes, from varicose veins to reticular veins and telangiectasias. It is relatively quick to perform by experienced practitioners and can be easily repeated as maintenance treatment.

Disadvantages

Disadvantages of UGFS include:11,12

- a higher five-year varicose vein recurrence with sclerotherapy alone compared with combination endovenous laser and sclerotherapy

- five-year failure rate above 20% for larger diameter veins (greater than 5 mm)

- potential for gas embolism

- higher likelihood of matting and hyperpigmentation (hemosiderin staining)

- longer time (months) for vein reabsorption and disappearance.

Rare but catastrophic complications specific to UGFS include sclerosant extravasation skin ulcers and inadvertent intra-arterial injection causing tissue ischaemia.11

Endovenous thermal ablation

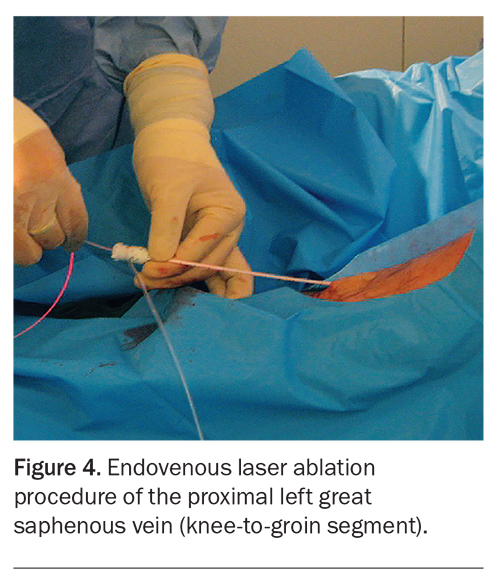

EVTA uses either radiofrequency or laser energies that are delivered via a catheter inside the vein (Figure 4). Radiofrequency devices appeared on the market first, but over time, there has been a proliferation of various laser devices with a range of wavelengths (810 nm, 980 nm, 1064 nm, 1320 nm and 1500 through to 1920 nm).13

The three steps to EVTA are: insertion of either the radiofrequency catheter or fibreoptic laser wire into the incompetent vein segment; injection of tumescent anaesthesia around the target vein (within its fascial sheath) to collapse the vein so that it is in close contact with the device wire; and activation of the energy device to heat ablate the treated vein segment as the device is withdrawn. The tumescent anaesthesia enveloping the treated vein offers excellent anaesthesia while protecting the surrounding tissue from collateral thermal injury and burns.

Advantages

EVTA is the first-line treatment for truncal veins, particularly if larger than 5 mm in diameter, as it has a 20-year track record of a five-year failure rate below 5%, making it the safest, most established and most effective modality for dilated proximal truncal veins.1 It is a ‘clean’, ‘in and out’ outpatient-based procedure performed under tumescent local anaesthesia that delivers laser or radiofrequency energy within the vein lumen to trigger heat-induced vein sclerosis.

Disadvantages

Owing to device and consumable (disposable laser fibres) overheads and requirements for laser safety accreditation, EVTA procedures are costly and are considerably higher when performed in a hospital setting. Laser-specific complications include laser-induced eye injury and thermal injury to the skin or subcutaneous structures; however, these are obviated by laser safety measures and effective tumescent anaesthetic, respectively.

Cyanoacrylate (glue) closure

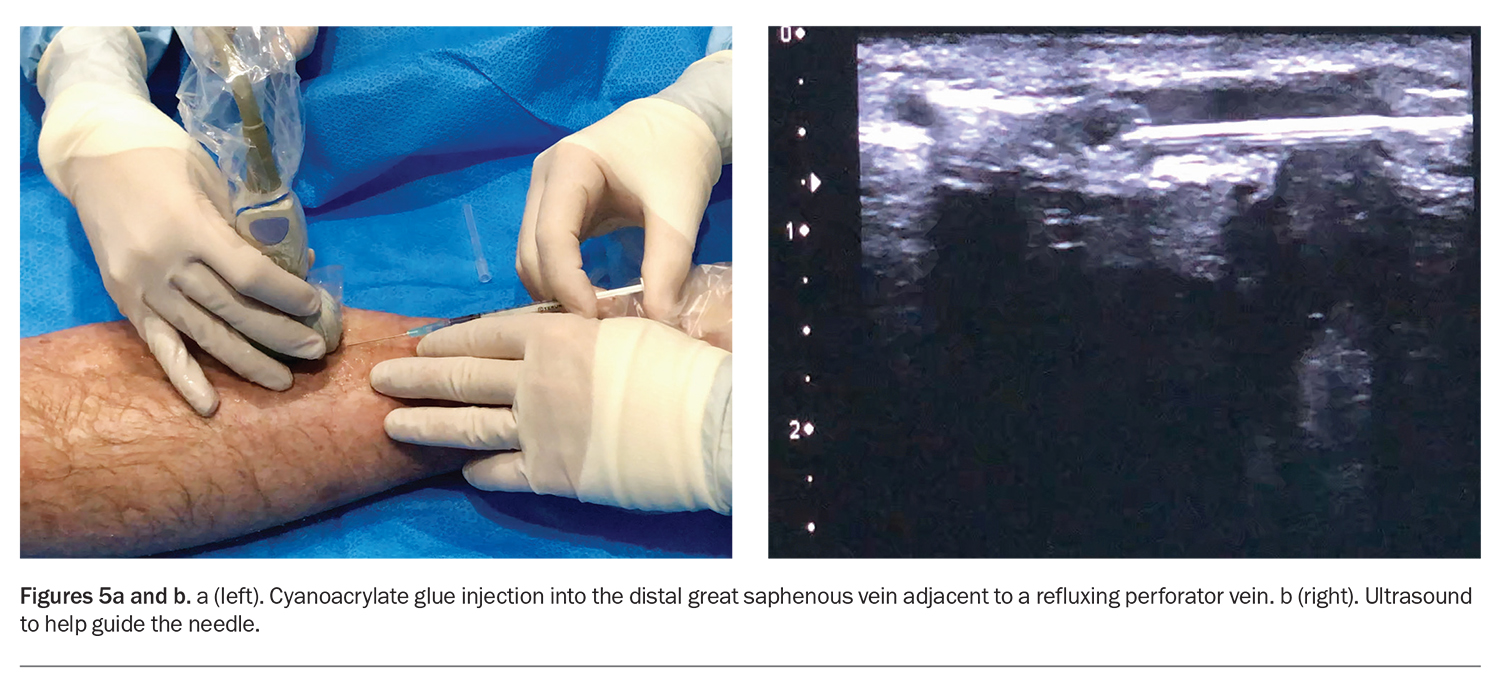

CAC is a recent adaptation of medical adhesive technology for varicose vein treatment. The medical grade adhesive is delivered to the varicose veins via a direct needle injection or soft catheter. CAC is a promising alternative to surgical vein stripping and EVTA.14 It is a minimally invasive, low-downtime procedure. It can be combined with UGFS. CAC is best for treating larger truncal veins whereas UGFS is best for the smaller tributary veins. Treating incompetent veins may limit and reverse varicose vein complications (Box 1).

CAC is performed under ultrasound guidance and does not require tumescent anaesthesia (Figure 5). As soon as the glue is delivered into the vein, external compression (with the hand or ultrasound probe) is applied for up to a minute or longer (depending on the type of glue), followed by a thermogenic (heat) reaction when the glue polymerises with blood contact.

Advantages

CAC is suitable for larger diameter veins similar to the indications for EVTA. It has a comparable five-year failure rate to EVTA (less than 5%) and patients do not need tumescent anaesthesia during the procedure.15 It is relatively straightforward to administer via either a catheter or by syringe injection, and is particularly useful for targeting focal areas, such as point perforator incompetence and shorter segment veins.

Disadvantages

Disadvantages of CAC include that it:

- is a relatively new technology with only five-year data available on its safety and efficacy

- is relatively costly, although with minimal set-up cost

- can cause potential allergic contact dermatitis and other hypersensitivity reactions in susceptible individuals.

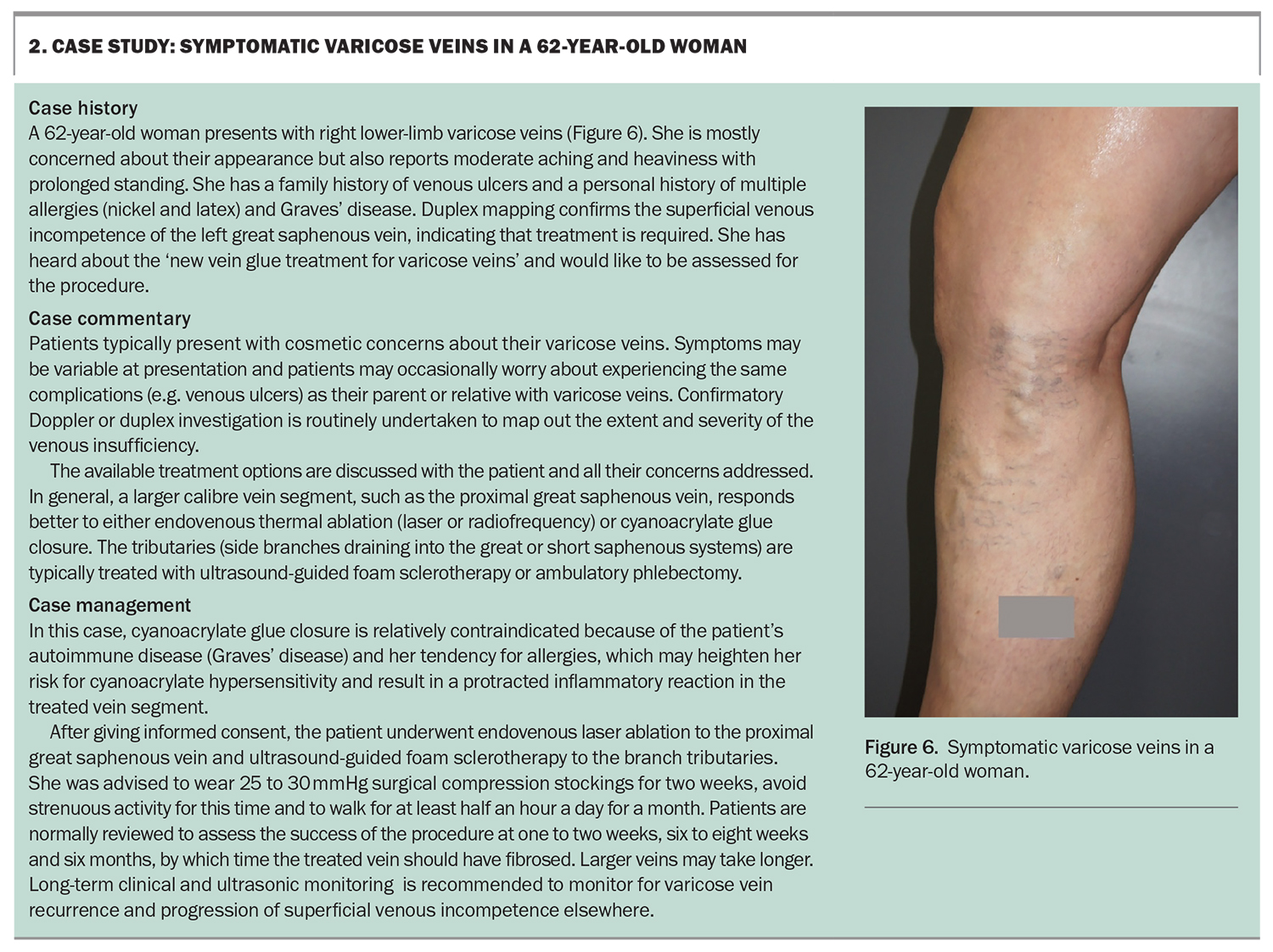

CAC is absolutely contraindicated for anyone with an acrylate allergy and relatively contraindicated for patients with multiple allergies or hypersensitivity reactions and those with autoimmune disorders. The persistence of the acrylate polymer within the veins (lasting over years and possibly permanent) means that any hypersensitivity reaction is likely to be chronic and may require surgical removal.

Ambulatory phlebectomy

Nontruncal veins, such as incompetent tributaries and tortuous varicosities, can be surgically removed with a stab avulsion technique termed ambulatory phlebectomy (AP). AP removes a short segment of veins through small incisions using special vein-removing hooks. Tortuous varicose veins are not suitable for treatment with EVTA methods because they do not readily permit passage of the device catheter or wire. In practice, many of these smaller tributaries can also be simply and effectively treated with ultrasound-guided sclerotherapy. AP is often combined with endovenous ablative techniques.

Advantages

AP offers a shorter recovery time than traditional stripping techniques. Surgical removal of the vein results in rapid improvement in appearance without the transitional vein sclerotic changes that often accompany other minimally invasive procedures.

Disadvantages

As AP requires a small skin incision, it has the possibility of leaving a small scar. The five-year recurrence is inferior to that of EVTA (over 20%) and the procedure is better suited to patients with larger and fewer varicose tributaries.1,6

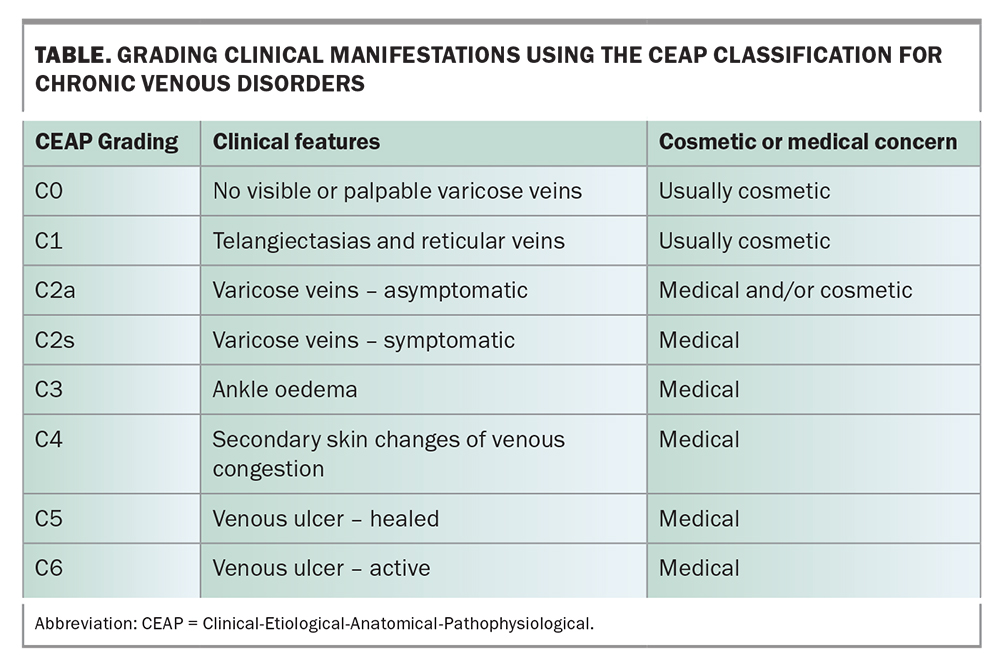

Patient-centred management

A careful history and examination of patients presenting with varicose veins will help define the clinical problem and allow a risk assessment of current and potential complications. These can be recorded using the Clinical-Etiological-Anatomical-Pathophysiological (CEAP) classification system, an international standard for describing manifestations of chronic venous disorders.16 Varicose vein presentations are graded according to clinical, ethological, anatomical and pathophysiological manifestations; each clinical grade is associated with medical or cosmetic concern and offers guidance on severity and interventional urgency. An abbreviated CEAP classification listing only clinical manifestations is presented in the Table.

Although patients may present primarily with pain and lower limb discomfort, these symptoms do not correlate well with the degree of venous insufficiency. The main drivers of treatment are cosmesis, symptom relief and patients’ concern over potential complications, such as leg ulcers, based on their observation of affected relatives. In practice, the precise treatment plan tends to be shaped by the patient’s unique medical history, social and financial situation and personal preference, in conjunction with the practitioner’s experience and expertise.17 A case study outlining the management of a patient with lower limb varicose veins is presented in Box 2.

Varicose vein journey

Varicose vein intervention can be delayed because of the lingering perception that the condition is invariably trivial and of cosmetic concern only.5 However, the varicose vein condition and associated venous insufficiency are progressive and, in extreme cases, severe venous disease can lead to thromboembolic complications and malignant changes (e.g. squamous cell carcinoma arising from chronic venous ulcers) that can be potentially limb threatening.3 Although it is not possible to predict who will experience complications of chronic venous insufficiency, risk factors for disease progression, such as family history, body mass index and activity level, appear to correlate with disease severity and progression.4

All patients with varicose veins, whether graded as cosmetic or medical, require regular clinical and ultrasonic monitoring – ranging from every one to three years, depending on CEAP classification, lifestyle and rate of disease progression. Patients need to appreciate that venous insufficiency and varicose veins are slowly progressive and may be complicated by acute and chronic events that can be mostly managed and prevented. Those with a cosmetic CEAP grading can be monitored without immediate procedural intervention. These patients need to understand that with time, treated veins may recur or new veins may develop. To maintain a cosmetically acceptable appearance, maintenance treatments are necessary and regular monitoring is recommended to identify and quantify disease progression across the CEAP grading.

Conclusion

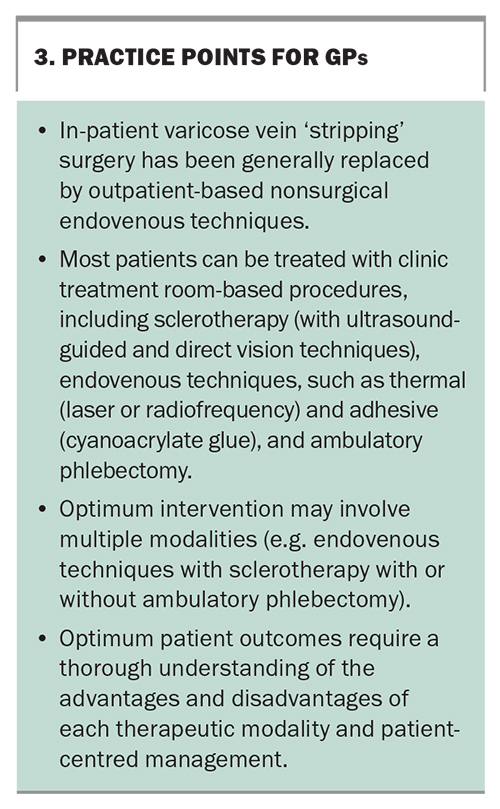

Although varicose veins frequently present as a cosmetic condition, they carry the potential for significant clinical morbidity. Hereditary and sedentary lifestyle factors are contributory, and the varicose vein condition typically worsens with age. Long-term follow up is recommended to monitor disease progression, vein recurrence after treatment and the development of chronic venous complications. Duplex mapping is required to assess the extent and severity of the underlying venous incompetence. Current procedural techniques are mostly nonsurgical, and the selection and combination of treatment methods are dependent on factors, such as venous pathology, patient medical history and preference, and practitioner expertise. Practice points are summarised in Box 3. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Lim has been on Technical Advisory Boards for NSW Department of Health; is Board Member for the Australasian College of Phlebology; and owns shares in EBOS Healthcare Australia. Dr Evly, Dr Jenkins: None.

References

1. Epstein D, Bootun R, Diop M, Ortega-Ortega M, Lane TRA, Davies AH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of current varicose veins treatments. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2022; 10: 504-513.e7.

2. Robertson L, Evans C, Fowkes FG. Epidemiology of chronic venous disease. Phlebology 2008; 23: 103-111.

3. Myers K, Hannah P, eds. Clinical presentations of chronic venous disease. Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742: Taylor and Francis Group, 2018.

4. Myers K, Hannah P, eds. Pathogenesis of varicose veins. Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742: Taylor and Francis Group, 2018.

5. Davies AH. The seriousness of chronic venous disease: a review of real-world evidence. Adv Ther 2019; 36(Suppl 1): 5-12.

6. National institute for health and care excellence (NICE). Varicose veins: diagnosis and management [CG168]. NICE; UK, July 2013.

7. Coleridge-Smith P, Labropoulos N, Partsch H, et al. Duplex ultrasound investigation of the veins in chronic venous disease of the lower limbs-UIP consensus document. Part I. Basic principles. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006; 31: 83-92.

8. Cowleridge Smith P. Sclerotherapy and foam sclerotherapy for varicose veins. Phlebology 2009; 24: 260-269.

9. Smith PC. Chronic venous disease treated by ultrasound guided foam sclerotherapy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006; 32: 577-583.

10. Bergan J, Cheng V. Foam sclerotherapy of venous malformations. Phlebology 2007; 22: 299-302.

11. Cavezzi A, Parsi K. Complications of foam sclerotherapy. Phlebology 2012; 27(Suppl 1): 46-51.

12. Brittenden J, Cotton SC, Elders A, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of foam sclerotherapy, endovenous laser ablation and surgery for varicose veins: results from the Comparison of LAser, Surgery and foam Sclerotherapy (CLASS) randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 2015; 19: 1-342.

13. Malskat WSJ, Engels LK, Hollestein LM, et al. Commonly used endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) parameters do not influence efficacy: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Sur. 2019; 58: 230-242.

14. Dimech AP, Cassar K. Efficacy of cyanoacrylate glue ablation of primary truncal varicose veins compared to existing endovenous techniques: a systematic review of the literature. Surg J (N Y). 2020; 6: e77-e86.

15. El Kilic H, Bektas N, Bitargil M, et al. Long-term outcomes of endovenous laser ablation, n-butyl cyanoacrylate, and radiofrequency ablation for treatment of chronic venous insufficiency. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2022; 10: 865-871.

16. Lurie F, Passman M, Meisner M, et al. The 2020 update of the CEAP classification system and reporting standards. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2020; 8: 342-352.

17. Campbell B, I JF, Gohel M. The choice of treatments for varicose veins: A study in trade-offs. Phlebology 2020; 35: 647-649.