Pharmacotherapy for the management of obesity

To develop obesity, it is necessary to have genetic or epigenetic differences that inhibit key negative feedback systems regarding hunger regulation. To counteract increased hunger, medications are required early in weight management, if not using ketosis as a weight loss strategy. Important considerations for treatment are the cost of non-PBS subsidised weight loss medications and the requirement for lifelong maintenance.

Medications that suppress hunger or increase satiety are important in assisting with weight loss in individuals with obesity, both initially and for maintenance. This article briefly discusses the aetiology of obesity, the control of hunger and reasons for which most patients regain lost weight, and then considers the medications.

Aetiology of obesity

Obesity is a chronic condition with strong evidence for a predominantly genetic or epigenetic basis. Adopted individuals resemble their biological parents and have no relationship in body weight to their adoptive parents.1 If a mother is starving while her baby is developing neurocognitively in the first three months in utero, that child will grow up as an obese individual.2 If parents consume a high energy diet as they conceive their child, they will imprint their eggs and sperm and produce overweight offspring.3

Factors that can modify weight but do not individually cause obesity include the modern lifestyle, gut bacteria, sleep deprivation, medications, medical disorders and menopause. Forced overfeeding studies from the USA have shown that despite a group of individuals being overfed by the same amount, there is a range of weight gain.4 Those who did not gain weight, spontaneously increased their daily energy expenditure by around 2000 kJ per day.

Biochemical control of hunger

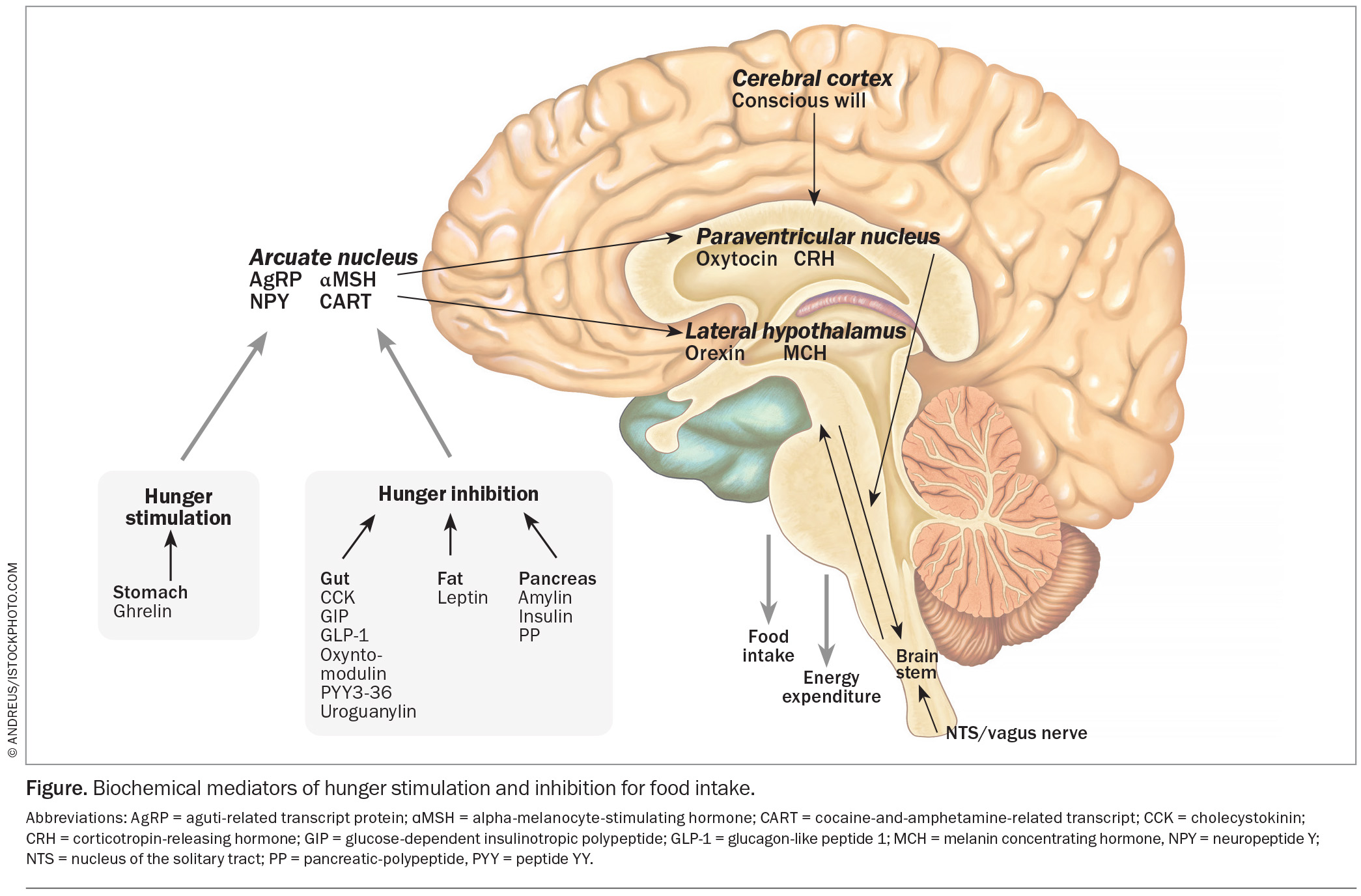

Circulating levels of hormones that control hunger change with weight loss, and promote hunger by the time an individual loses 5% body mass. The genetic basis of obesity provides an explanation for the vigorous defence of body weight through regulatory mechanisms within the brain. In the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, two types of neurons control hunger: the neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons, which produce neuropeptide Y and agouti-related protein (AgRP), both of which stimulate hunger; and the pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, which produce alpha-melanocyte-stimulating-hormone (aMSH) and cocaine- and-amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART), both of which inhibit hunger. These neurons project to other areas of the hypothalamus.

The degree of hunger depends on the relative activities of the NPY and POMC neurons. This activity is determined by inputs into the arcuate nucleus from the pleasure areas of the brain or received as signals from the gastrointestinal tract transmitted via the vagus nerve in the brainstem, and from circulating hormones. Such hormones include ghrelin from the stomach, which stimulates hunger; cholecystokinin, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP), glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), oxyntomodulin, uroguanylin and peptide YY from the small bowel; and amylin, insulin and pancreatic polypeptide from the pancreas, all of which inhibit hunger (Figure).

Weight management

Following even modest weight loss,5 hormone changes in the blood lead to increased hunger and to a long-lasting reduction in energy expenditure.5,6 Thus, hunger suppressing medications or medications that increase satiety may have a crucial role in assisting with weight loss – initially, and more importantly, for maintenance.

Ketogenic diets are also successful treatments for weight loss. Ketones suppress hunger by acting directly on the brain, and by stabilising circulating levels of some of the hormones attributed to controlling hunger.7

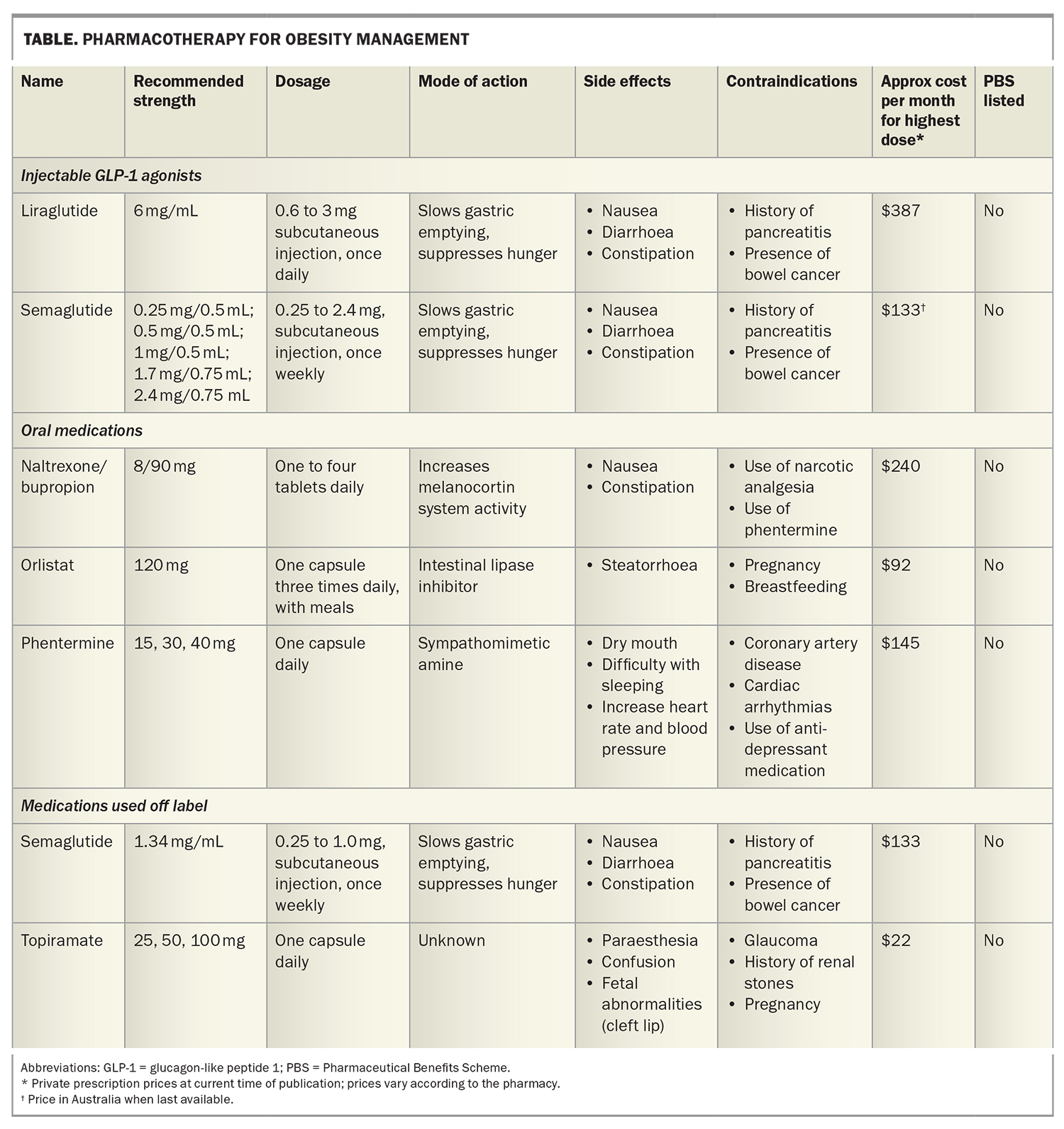

Medications used for weight management are listed in the Table and discussed briefly below. It should be noted, however, that not all these medications are approved by the TGA for use in weight management in Australia.

GLP-1 agonists

Although GLP-1 agonists are used to lower glucose levels in patients with diabetes, they do not cause hypoglycaemia in individuals who do not have diabetes. This is because

GLP-1 only stimulates insulin secretion in the presence of an elevated glucose level.

Liraglutide is a GLP-1 agonist with hunger-suppressing action. It is administered by a daily subcutaneous injection with a starting dose of 0.6 mg. Because it can cause nausea, which settles after continued use, the dose should be slowly increased to 3 mg daily, if required.

Semaglutide 2.4 mg is approved by the TGA for the management of obesity, and is administered as a weekly subcutaneous injection. Semaglutide 1 mg has not been approved for use in obesity, but is effective in managing obesity in some patients. Recently (mid-2022 onwards), there has been a global shortage of semaglutide since the production facility in Denmark has been unable to keep up with the demand for a medication that can be used to treat the two common conditions: type 2 diabetes and obesity. Production facilities are being increased so the shortage should end soon.

Phentermine, orlistat and naltrexone/bupropion

Phentermine is a sympathomimetic amine that acts on the brain to inhibit hunger. It is available in three strengths:

15 mg, 30 mg and 40 mg.

Orlistat is an intestinal lipase inhibitor that slows fat digestion and is available in pharmacies without prescription. Because it does not inhibit hunger, it does not have a role in weight maintenance.

The combination of naltrexone and bupropion works by increasing activity of the melanocortin system in the hypothalamus. The starting dose is one tablet (8 mg naltrexone and 90 mg bupropion) daily, gradually increasing to two tablets twice daily.

Topiramate

Topiramate is not TGA approved for the management of obesity and is hence used off label for weight management. It has frequent side effects at higher doses, such as paraesthesia, confusion, raised intraocular pressure and an increased risk of renal stones. The starting dose should be low (12.5 to 25 mg daily).

Considerations when selecting treatment

For nearly all weight management medications, there is a wide range of patient response, for both efficacy and side effects; a dose that works well with no side effects for one individual can have intolerable side effects or be ineffective for another. All doctors should warn their patients that this is the case, and then, by mutual agreement, start one medication and be prepared to change to another if the first is intolerable or ineffective.

Obesity rates are higher in areas of lower socioeconomic status. Cost to the individual patient must be considered, with all of these medications of these medications lacking PBS subsidy. When considering cost, efficacy and convenience (a weekly injection), semaglutide 1 mg per week may be the first medication to try, provided the patient does not have needle phobia.

Another issue to consider is whether multiple medications may be required, given there are eight hormones to suppress hunger after a meal (cholecystokinin, peptide YY, GLP-1, oxyntomodulin, uroguanylin, pancreatic polypeptide, amylin and insulin). If each of several medications is used at a low dose, some of the side effects may be avoided. Phentermine can be combined with topiramate (available as a single capsule in the USA; in Australia, separate prescription is required).8 Liraglutide or semaglutide can be combined with phentermine and topiramate, or naltrexone/bupropion.

The two medications that should not be combined are naltrexone/bupropion and phentermine. This is because bupropion has antidepressant effects and may increase cerebral serotonin. This is usually harmless in the circulatory system, due to the avid uptake of serotonin by red blood cells; however, the addition of phentermine inhibits the uptake of serotonin by red blood cells and may result in elevated circulating serotonin levels, which has been shown to cause heart valve fibrosis.

Conclusion

Managing weight is challenging for patients and their treating physicians. There is increasing evidence for genetic and epigenetic neuronal and hormonal mechanisms that prevent weight loss. Medications can counteract these measures, and selection of an appropriate agent must consider the potential efficacy, adverse effects, combination with other treatments, and cost to the patient. It is essential that weight management medications are used beyond the initial weight loss phase for maintenance. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Professor Proietto is on Medical Advisory Boards for, and has received payment for taking part in the Horizon Program at, Novo Nordisk, and has received payment for lectures on behalf of iNova.

References

1. Stunkard AJ, Sorensen TI, Hanis C, et al. An adoption study of human obesity. N Engl J Med 1986; 314: 193-198.

2. Ravelli GP, Stein ZA, Susser MW. Obesity in young men after famine exposure in utero and early infancy. N Engl J Med 1976; 295: 349-353.

3. Huypens P, Sass S, Wu M, et al. Epigenetic germline inheritance of diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Genet 2016; 48: 497-499.

4. Levine JA, Eberhardt NL, Jensen MD. Role of nonexercise thermogenesis in resistance to fat gain in humans. Science 1999; 283: 212-214.

5. Edwards KL, Prendergast LA, Kalfas S, Sumithran P, Proietto J. Impact of starting BMI and degree of weight loss on changes in appetite-regulating hormones during diet-induced weight loss. Obesity 2022; 30: 911-919.

6. Sumithran P, Proietto J. The defence of body weight: a physiological basis for weight regain after weight loss. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013; 124: 231-241.

7. Sumithran P, Prenergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Ketosis and appetite-mediating nutrients and hormones after weight loss. Eur J Clin Nutr 2013; 67: 759-764.

8. Neoh SL, Sumithran P, Haywood CJ, Houlihan CA, Lee FTH, Proietto J. Combination phentermine and topiramate for weight maintenance: the first Australian experience. Med J Aust 2014; 201: 224-226.