Was it something I ate? Managing GI-related cow’s milk allergy in infants

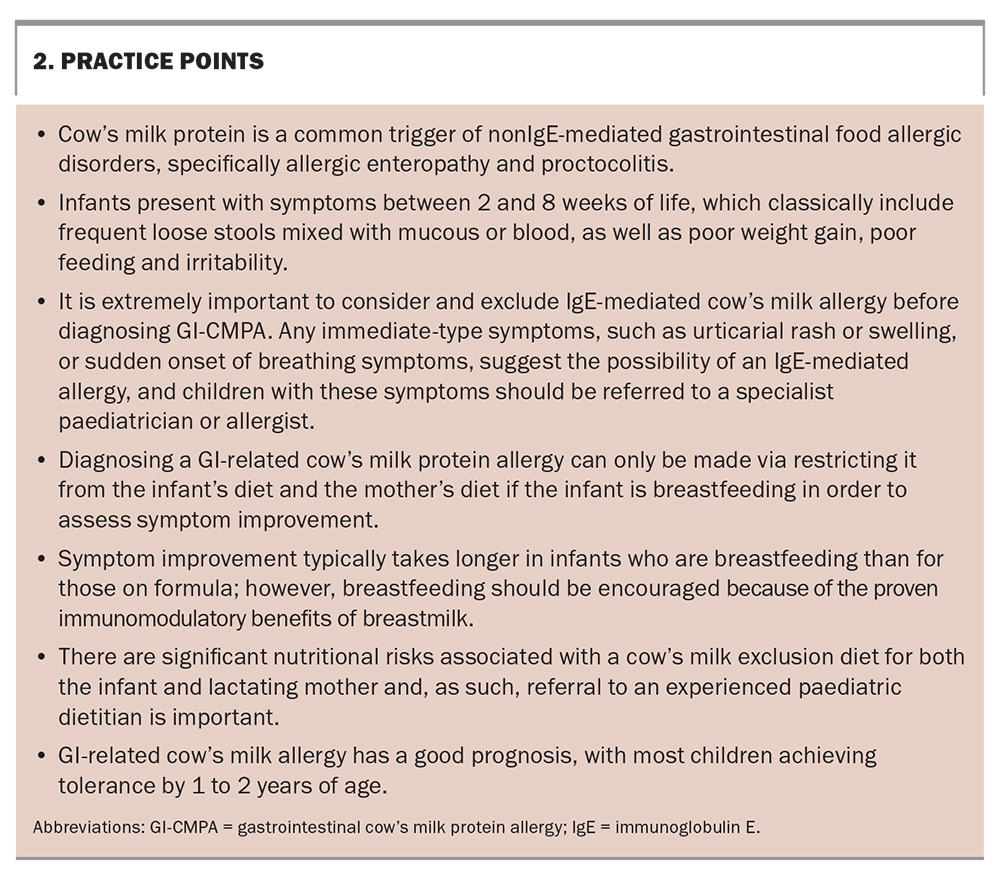

Managing an unsettled baby is a source of stress for parents. When unsettled behaviour is also associated with a change in stool consistency, stool frequency, poor feeding and poor growth, a diagnosis of nonIgE-mediated cow’s milk protein allergy should be considered and differential diagnoses, including an IgE-mediated allergy, infection, very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease and lactose intolerance, excluded. Management is largely through an elimination diet, with reintroduction of suspected food groups and assessment for associated symptoms. Involvement of an experienced paediatric dietitian is important to help maintain infant and maternal nutrition.

Cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) is one of the most common food allergies in infants and children, with a prevalence of 2 to 5%.1 CMPAs encompass a number of conditions, including both IgE-mediated and nonIgE-mediated allergies. NonIgE-mediated allergies to cow’s milk often lead to adverse gastrointestinal symptoms. The most common nonIgE-mediated allergic conditions in infants are cow’s milk protein- (CMP)-induced enteropathy and CMP-induced proctocolitis. Diagnosis and treatment involve the exclusion of CMP products from the infant’s diet, with an eventual challenge once symptoms have resolved. Avoidance of cow’s milk in both infants and lactating mothers needs to be undertaken under careful guidance to ensure the exclusion diet is followed strictly for optimal therapeutic benefit and to prevent nutrition-related adverse outcomes, such as poor growth in infants and suboptimal energy, insufficient protein and calcium intake and reduced bone mineral density in mothers.

This article summarises the diagnosis and management of this condition and highlights the importance of dietetic involvement for mothers and infants following an exclusion diet. For the purpose of this article, gastrointestinal cow’s milk protein allergy (GI-CMPA) will refer to nonIgE-mediated gastrointestinal reactions to cow’s milk, specifically CMP-induced enteropathy, allergic colitis and proctocolitis.

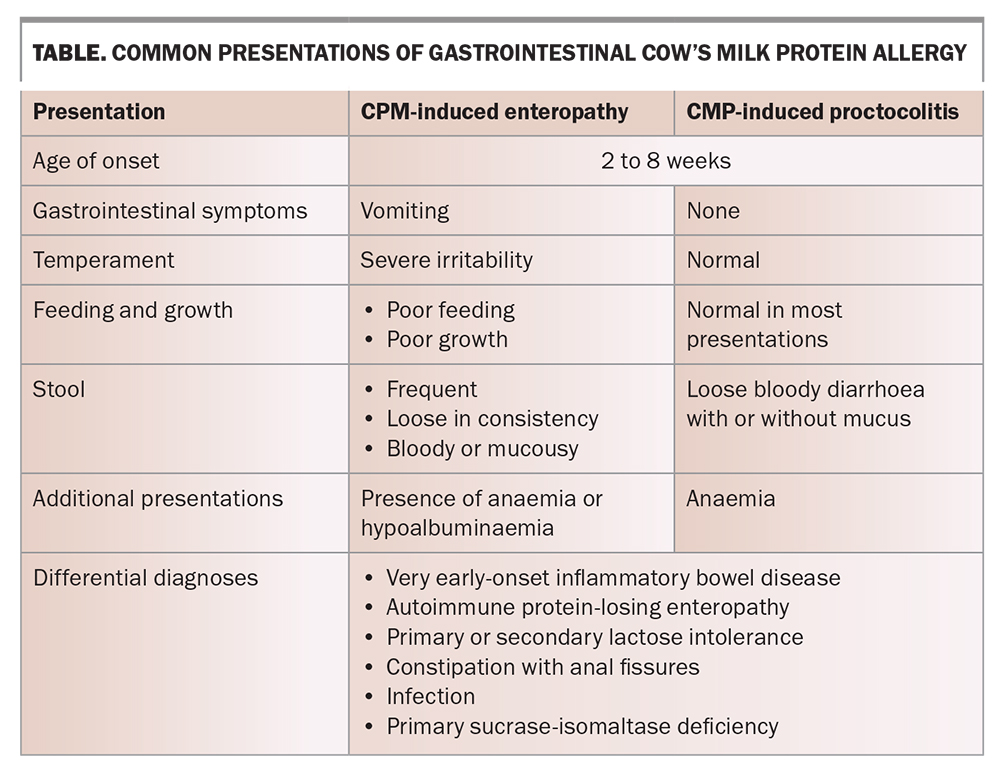

Common presentation of GI-CMPA

GI-CMPA in infants presents as a delayed reaction to cow’s milk, either via cow’s milk-based infant formula or beta-lactoglobulin protein in breastmilk, which is present when the maternal diet contains dairy. As GI-CMPA encompasses a number of clinical conditions, it is important to understand the different presentations that may occur (Table). Infants will often present with symptoms between 2 and 8 weeks of age. Symptoms are diverse and can range from mild to severe in nature. Common symptoms of CPM-induced enteropathy include vomiting, severe irritability, poor feeding and poor growth. Stools are generally frequent and loose in consistency, and can be mixed with mucous or blood. As a result, infants can uncommonly experience anaemia or hypoalbuminaemia. For infants with CMP-induced proctocolitis who are otherwise well and thriving, symptoms are usually isolated to loose, bloody diarrhoea. In making these diagnoses, other conditions with similar presentations, such as very-early onset inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune protein-losing enteropathy, lactose intolerance and constipation with anal fissures, must be considered and excluded.

Diagnosis of GI-CMPA

The first step in diagnosing GI-CMPA is to take a thorough medical history and perform a physical examination. If an infant presents with the above symptoms that cannot be explained by another cause (including infection, very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune protein-losing enteropathy, oromotor feeding delays or primary sucrase-isomaltase deficiency), GI-CMPA needs to be considered. It is extremely important to also consider and exclude IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy before diagnosing GI-CMPA. Any immediate-type symptoms, such as urticarial rash or swelling, or sudden onset of breathing symptoms suggest the possibility of an IgE-mediated allergy. Children with these symptoms should be referred to a paediatrician or paediatric allergist for further evaluation.

A diagnosis of GI-CMPA can be facilitated by performing stool microscopy checking for the presence of red and white blood cells and a blood test to ensure there is no hypoalbuminaemia or anaemia, and by excluding infection. A physical examination should check for the presence of anal fissures, which may account for blood within stools. As CMP enteropathy and proctocolitis are types of GI-CMPA, a child will typically have a negative skin prick wheal on allergy testing. No specific diagnostic tests for GI-CMPA exist; a formal diagnosis can only be confirmed if a clinical response after excluding dairy from the diet for a set period of time, and then a recurrence of symptoms following a careful reintroduction, are observed.2 Once a diagnosis of GI-CMPA is made, the child should remain on the therapeutic diet for at least six months or until they are 9 to 12 months of age.2

Other food intolerances implicated in GI-CMPA

Adverse reactions to soy have been reported in 10 to 35% of children with CMPA.3 Less commonly, egg and wheat have also been implicated as triggers in children with multiple food allergies.4 A dairy- and soy-free diet and maternal diet is often advised for infants with moderate to severe symptoms, with the potential exclusion of egg or wheat, or both, if their symptoms persist. Nontrigger foods may be selected when excluding multiple foods from the diet; therefore, each food should be reintroduced individually to ensure it is truly implicated in the symptoms before excluding it longer term.

As there is little evidence that other common allergens are associated with GI-CMPA, a heavily restricted diet is not advised for mothers and their infants. A severely restricted diet has adverse effects on the nutritional adequacy of both the mother and child, placing them at a high risk of micronutrient deficiencies, poor weight gain for the infant, and weight loss for the mother. Additionally, limiting the infant’s exposure to a wide range of food antigens may increase their risk of developing IgE-mediated food allergies over time.5 If symptoms do not improve after eight weeks on an exclusion diet, it should be discontinued and other causes investigated.

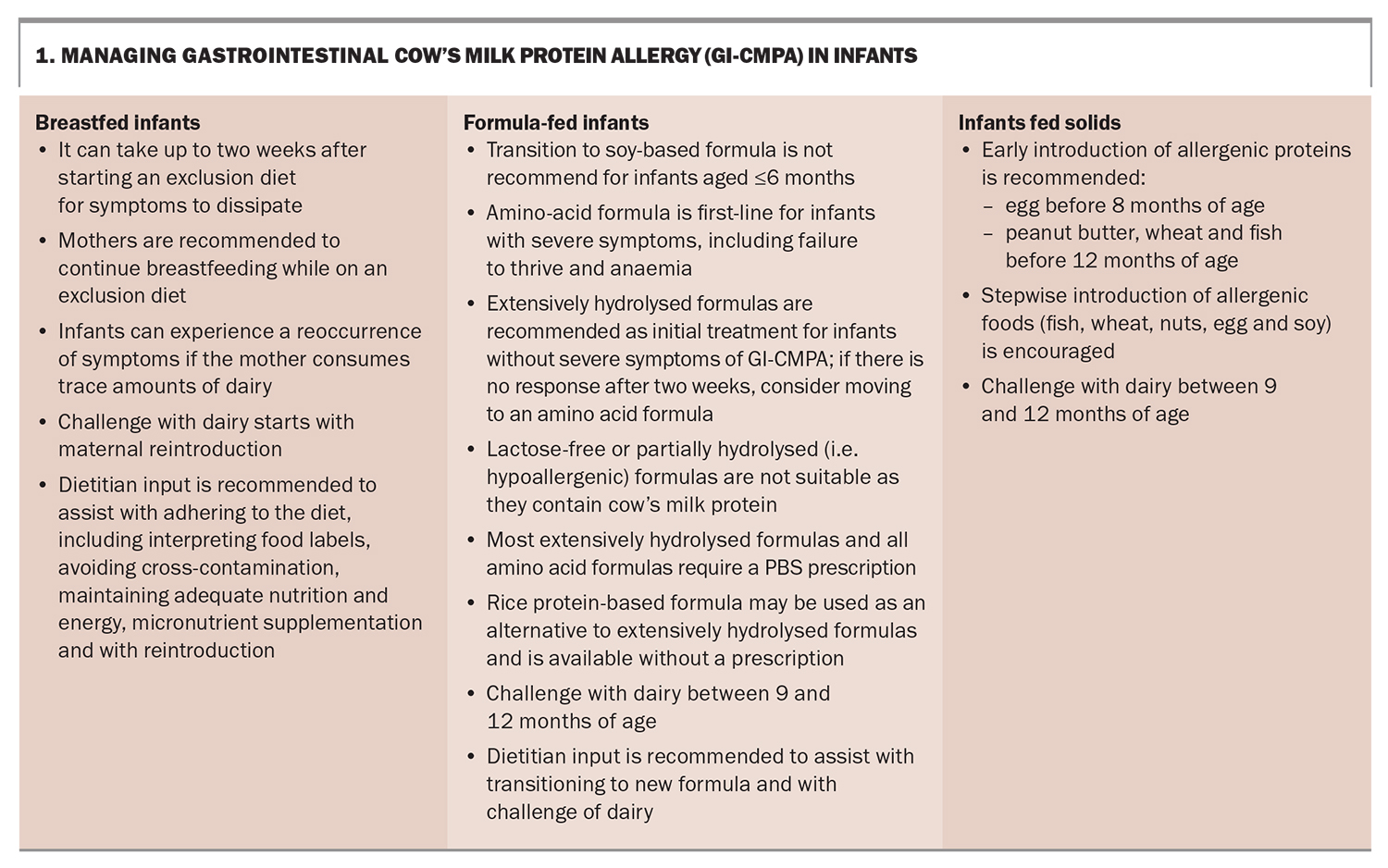

Management of GI-CMPA in breastfeeding infants

Mothers of breastfeeding infants with suspected GI-CMPA are advised to follow a strict cow’s milk-free diet (Box 1). There is growing evidence and support for mothers to continue to breastfeed while following a maternal exclusion diet. Immunomodulators present in breast milk and differences in the gut flora between breast-fed and formula-fed infants may lead to improved gut adaptability to CMP and generally less severe symptom manifestations in breast-fed infants.6

Breastfeeding infants take longer to show a clinical improvement in their symptoms, and changes may not be noticed until 14 days after commencement of a maternal exclusion diet. Infants with severe GI-CMPA can be transitioned onto formula for a two- to three-week period while the mother expresses and discards her breastmilk to remove any residual beta-lactoglobulin that may be present. Referral to an experienced dietitian is recommended to provide education on the importance of strict maternal avoidance of cow’s milk, including information on reading labels, minimising cross-contamination and practical strategies for eating out. Dietitian input also ensures that the mother maintains adequate energy, protein and micronutrient intake while on an exclusion diet. Mothers will often need to take a calcium supplement or multivitamin to help meet their requirements. A dietitian can provide advice on dairy-free nutritional supplements and ensure any other medications or supplements are dairy free. If the mother accidentally consumes a trace amount of dairy, the infant may become symptomatic again. If this occurs, and depending on the severity of the symptoms, the mother may wish to continue to breastfeed, or express and discard her breast milk and feed the infant CMP-free formula for a period of time until the infant’s symptoms dissipate.

Management of GI-CMPA in formula-fed infants

It is advised that infants already fed with formula are transitioned onto an extensively hydrolysed formula, which has proven efficacy in infants with GI-CMPA.7 Transitioning to soy formula can also be considered; however, this is only recommended for infants older than 6 months of age. Rice protein-based formula may be used as an alternative to an extensively hydrolysed formula; however, this should not be used in infants with a history of food protein-induced enterocolitis to rice. For infants with severe symptoms, particularly failure to thrive and anaemia, an amino acid formula may be considered as the first choice. Neither lactose-free or partially hydrolysed formulas (those marketed as hypoallergenic) are suitable for children with GI-CMPA due to the presence of intact CMP.

Transitioning infants to a hydrolysed or amino acid formula can be challenging because of the overt taste differences: these specialised formulas tend to be quite bitter and strong in taste. An experienced dietitian can assist with this transition, which may involve mixing the infant’s usual formula with the new formula for a period of time or adding flavourings to disguise the taste of the new formula.

Most extensively hydrolysed formulas and all amino acid formulas require a PBS prescription, with some having a restricted benefit and others requiring authority with PBS. Details of the prescribing requirements for the different formulas can be found on the PBS website (https://www.pbs.gov.au/).

Introduction of solids

It is now widely understood that, contrary to previous recommendations, there is no obvious benefit in delaying the introduction of solid foods to assist in the prevention of food allergies. Additionally, the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy recommends early introduction of allergenic proteins, with introduction of egg before 8 months of age, and other common allergens, including peanut butter, wheat and fish, before the age of 12 months to assist with the prevention of food allergies.8 Infants should be started on solids when they are showing developmental signs of readiness, at around 6 months of age, but not before the age of 4 months.8,9 The process of introducing solids to children with GI-CMPA is very similar to that for nonallergic infants. Parents should be educated on the importance of reading food labels and avoiding foods containing CMP. The introduction of other allergenic foods, such as fish, wheat, nuts, egg and soy, is encouraged in a step-wise manner.

Challenging dairy into the diet

Infants with GI-CMPA who have responded to an elimination diet should be challenged with dairy at between 9 and 12 months of age.2 An experienced paediatric dietitian can provide guidance on challenging the infant with dairy at home. A child with an atopic history, such as significant eczema or IgE-mediated food allergy to another food, may be at risk of a concurrent IgE-mediated CMPA. In this instance, a referral to a paediatric allergist for assessment should be considered. In breastfeeding infants, the dairy challenge will typically first involve the mother introducing dairy into her diet and, if this does not exacerbate the child’s gastrointestinal symptoms, dairy is introduced into the child’s diet.

The type and pace of the dairy challenge should be individualised to each child, with consideration of the severity of their prior reactions. If the child shows recurrent symptoms when dairy is reintroduced, it is recommended they remain on a dairy-free diet, with a review and potential rechallenge every six to 12 months.10 Such infants should be closely monitored by a paediatric dietitian, as nutritional requirements increase after the age of 12 months and guidance to achieve nutrient adequacy without dairy must be provided.

GOR and GI-CMPA

Gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) is a normal physiological process that involves the passage of gastric contents into the oesophagus with or without regurgitation or vomiting.11 GOR occurs most frequently in infants under 12 months of age. GOR disease (GORD) occurs when GOR leads to troublesome symptoms that affect daily functioning, clinical status, or both. Symptoms can vary in severity from irritability and poor feeding to poor growth, apparent life-threatening events and recurrent pneumonia associated with aspiration.11 A subset infants with GI-CMPA present with regurgitation, vomiting and poor growth, which are also similar to the symptoms of GORD.12 For this reason, international guidelines recommend a two-week trial of an extensively hydrolysed protein formula, or maternal exclusion diet for breastfed infants, for patients who have not responded to conservative GORD therapies in order to rule out GI-CMPA.11 Cow’s milk formula or cow’s milk should then be reintroduced into the maternal diet to monitor for symptom recurrence. Clinicians should also consider a diagnosis of infantile eosinophilic oesophagitis in infants whose GORD symptoms respond to a cow’s milk-free diet but reoccur after reintroduction of dairy, particularly in those with significant feeding difficulties, dysphagia and difficulty with transitioning to variable food textures. Referral to a paediatric gastroenterologist is recommended for infants with persistent failure to thrive, vomiting, altered bowel habits and if there is a concern for eosinophilic oesophagitis.

The irritable baby and GI-CMPA

Colic is characterised by episodes of unexplained infantile crying during the early weeks of life. Although the term colic suggests involvement of the gastrointestinal tract, the causes are likely to be multifactorial. Infants with colic typically do not have specific GI-related symptoms and are otherwise well and thriving. GI-CMPA has been associated with colic in some studies, with children exhibiting improvement in symptoms on extensively hydrolysed or soy formula, or a maternal exclusion diet.4 However, a definitive relationship is difficult to establish because of the often transient nature of colic secondary to rapid maturation of the gut within the first few months of life.

Nutritional implications of a dairy-free diet

It is well established that any exclusion diet in infants, particularly a dairy-free diet, can impact on their nutritional status. A Brazilian study found that, of 513 patients with CMPA, 15% were underweight, 24% were stunted and 9% were malnourished.13 Dairy is a rich source of protein, fat, energy and micronutrients such as calcium, phosphate, vitamin B12 and vitamin A. The exclusion of dairy can reduce total energy intake, which impacts growth and development. More concerningly, longer-term dairy exclusion has been associated with poorer bone health and short stature.14 Children on a dairy-free diet have been shown to have lower vitamin D levels compared with children on an unrestricted diet. This trend was seen most often in predominantly breastfed infants and thought to be directly related to the vitamin D status of the lactating mother.15 Additionally, prepubertal children on a dairy-free diet were found to have significantly lower lumber spine bone density compared with children on an unrestricted diet.16 Therefore, it is important for a child on any type of exclusion diet (but particularly a dairy-free diet) to receive ongoing support and education with an experienced paediatric dietitian. A recent Italian study found positive improvements in the nutritional status of infants with food allergy following six months of dietetic counselling, including an increase in weight-for-age z-scores and an increase in total energy, protein, calcium and zinc intake.17

A mother’s nutritional status while on an exclusion or dairy-free diet should be assessed and monitored, and education provided on energy-dense foods, particularly if the mother is losing weight rapidly. Mothers with suboptimal intake of calcium-fortified milk alternatives may need to take a calcium supplement.

Most plant-based cow’s milk alternatives (e.g. rice milk, coconut yoghurt and nut-based cheese products) vary in nutritional quality and are not nutritionally equivalent to cow’s milk-based products, particularly in regards to calcium, phosphate, protein and fat content. Research has shown lactating mothers on a dairy-free diet have a significantly decreased intake of total energy, protein and phosphorous compared with lactating mothers on an unrestricted diet. Additionally, mothers on an exclusion diet had more pronounced bone turnover, even though they were on appropriate calcium supplementation. Although bone loss has been found to be restored once breastfeeding is ceased, the effects of an exclusion diet on the bone health of mothers who breastfeed for an extended period of time is not well known.18

Conclusion

GPs are often the first point of contact for parents seeking advice when their child begins to show gastrointestinal symptoms, and have an important role in assessing infants for nonIgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies. A thorough assessment includes the consideration of differential diagnoses, such as allergies to other proteins, GOR or colic. If a diagnosis of GI-CMPA is suspected, an exclusion diet is recommended and early referral to a paediatric dietitian is useful in providing guidance on a dairy-free diet, with a focus on ensuring both the mother and infant meet their nutritional requirements. It is important for parents to feel supported, as many find it challenging to implement a food exclusion diet. Referral to a paediatric gastroenterologist or paediatric immunologist should also be considered, particularly for children who have poor growth, who are on a severely restricted diet, have feeding difficulties or have an atopic history. Practice points are presented in Box 2. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Ms Dehlsen is Secretary of the AuSPEN Home Parenteral Nutrition Committee. Associate Professor Lemberg: None.

References

1. Pensabene L, Salvatore S, D’Auria E, et al. Cow’s milk protein allergy in infancy: a risk factor for functional gastrointestinal disorders in children? Nutrients 2018; 10:1716-1730.

2. Koletzko S, Niggermann B, Arato A, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastorenterol Nutr 2012; 55: 221-229.

3. Klemola T, Vanto T, Juntunen-Backman K, Kalimo K, Korpela R, Varjonen E. Allergy to soy formula and to extensively hydrolyzed whey formula in infants with cow’s milk allergy: a prospective, randomized study with a follow-up to the age of 2 years. J Pediatr 2002; 140: 219-224.

4. Caubet J-C, Szajewska H, Shamir R, Nowak-Wegrzyn A. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergies in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2017; 28: 6-17.

5. Chang A, Robison R, Singh AM. Natural history of food triggered atopic dermatitis and development of immediate reactions in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2016; 4: 229-236.

6. Vandenplas Y, Brueton M, Dupont C. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants. Arch Dis Child 2007; 92: 902-908.

7. Fiocchi A, Schunemann HJ, Brozek J, et al. Diagnosis and rationale for action against cow’s milk allergy (DRACMA): a summary report. J allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126: 1119-1128.

8. Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy (ASCIA). Guidelines for infant feeding and allergy prevention. Sydney: ASCIA; 2016. Available online at: https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/papers/infant-feeding-and-allergy-prevention#:~:text=All%20infants%20should%20be%20given,for%20prevention%20of%20allergic%20disease (accessed September 2023).

9. National Health and Medical Research Council (NRMRC). Infant feeding guidelines. Canberra: NRMRC; 2012. Available onlibe at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/infant-feeding-guidelines-information-health-workers (accessed September 2023).

10. Lifschwitz C, Szajewska H. Cow’s milk allergy: evidence-based diagnosis and management for the practitioner. Eur J Pediatr 2015: 174: 141-150.

11. Rosen R, Vandenplan Y, Singendonk M. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guides: joint recommendations of the North American Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2018; 66: 515-554.

12. Nielsen RG, Bindslev-Jensen C, Kruse-Andersen S, Husby S. Severe gastroesophageal reflux disease and cow milk hypersensitivity in infants and children: disease association and evaluation of a new challenge procedure. JPGN 2004; 39: 383-391.

13. Vieira MC, Morais MB, Spolidoro J, et al. A survey on clinical presentation and nutritional status of infants with suspected cow’s milk allergy. BMC Pediatr 2010; 10: 25-31.

14. Celik MN, Koksal E. Nutrition targets in cow’s milk protein allergy: a comprehensive review. Curr Nutr Rep 2022; 11: 329-336.

15. Silva CM, Silva SAD, Antunes MMC, Silva GAPD, Sarinho ESC, Brandt KG. Do infants with cow’s milk protein allergy have inadequate levels of vitamin D? J Pediatr 2017; 93: 632-638.

16. Mailhot G, Perrone V, Alos N, et al. Cow’s milk allergy and bone mineral density in prepubertal children. Pediatr 2016; 137: e20151742.

17. Berni Canani R, Leone L, D’Auria E, et al. The effects of dietary counselling on children with food allergy: a prospective, muliticenter intervention study. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014; 114: 1432-1439.

18. Rajani PS, Martin H, Groetch M, Jarvinen K. Presentation and management of food allergy in breastfed infants and risks of maternal elimination diets. J Allergy Clin Immunol Prac 2020; 8: 52-67.