Infant feeding and growth: practical guidance on assessment and monitoring

Growth has long been a surrogate marker for overall health and successful feeding in infants. Quantifying intake from direct breastfeeding can be difficult; hence, monitoring growth and output over time is essential to assess an infant's progress. Multidisciplinary feeding support is important to assess, manage and monitor infants with feeding issues and support parents in their feeding journeys.

- Growth monitoring is important in assessing the adequacy of an infant’s breastmilk or formula intake.

- Collecting accurate serial growth measures is essential to assess a patient’s progress over time, correcting for prematurity (less than 37 weeks’ gestation) if applicable.

- Breastfeeding is a skill that takes time to learn. Feeding difficulties are common, especially in the early weeks of an infant’s life; therefore, it is important for parents to be able to access support to manage and maintain a positive breastfeeding relationship.

- Multidisciplinary support from a maternal child health nurse, lactation consultant or paediatric dietitian can help with assessment, intervention (e.g. maximising feeding, fortification strategies, top-up feeds) and ongoing monitoring of infant feeding and growth.

- Further investigation is warranted in cases where maximising feeding and fortification strategies have not resulted in a change in growth trajectory.

The GP is a trusted health professional from whom parents often seek advice and guidance about feeding and growth. All children are expected to grow steadily, but growth is particularly rapid in infancy. Establishing feeding helps to support this rapid growth, and clinical judgement is needed to interpret infant growth and manage feeding challenges as they arise.

Measuring growth

The WHO growth charts should be used to plot serial growth measures for infants under the age of 2 years.1 These growth charts were developed based on the Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS 1997-2003), with serial growth measures taken in healthy breastfed infants from diverse ethnic backgrounds.2 The charts can be used to assess the growth of any child, regardless of ethnicity, socioeconomic status and type of feeding. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) growth charts were previously used in Australia to track the growth of infants; however, they were based on a US population of predominantly formula-fed infants.3 Since 2012, all Australian states and territories have agreed to use the WHO charts for infants aged 0 to 2 years, with the CDC charts generally used for children aged 2 to 18 years.3

Separate charts are available for weight, length (or height) and head circumference for boys and girls in the different age groups and should be measured as follows.4

- Infants under the age of 12 months should have a bare weight measured to allow for consistent comparison, as nappy weight can vary significantly between wet and dry, and the weight of clothing can vary across seasons.

- Measurement of supine length should be performed until the age of 2 years. A second person should assist to ensure the baby’s head is held against the headboard. The baby should be lying straight (not at an angle) and their legs gently straightened with the soles of their feet flat against the footboard and their toes pointing upwards. Standing height can be measured in children close to 2 years of age who can stand unassisted.

- Head circumference should be measured using a measuring tape that cannot be stretched (e.g. a paper tape), with the tape wrapped around the head at the widest possible circumference (usually just above the eyebrows and around the back of the head).

Measuring growth of premature babies

Monitoring the growth and progress of premature babies is particularly important. Growth measurements of babies born before 37 weeks’ gestation should be corrected up to the age of 2 years to allow for assessment of progress for their corrected gestational age, rather than against babies of the same chronological age.4 Correcting growth measures consistently is important to ensure that the baby is being compared against their own previous measures. Feeding is a skill that requires energy and practice, and premature babies may require extra support to develop efficient feeding skills.

Interpreting growth

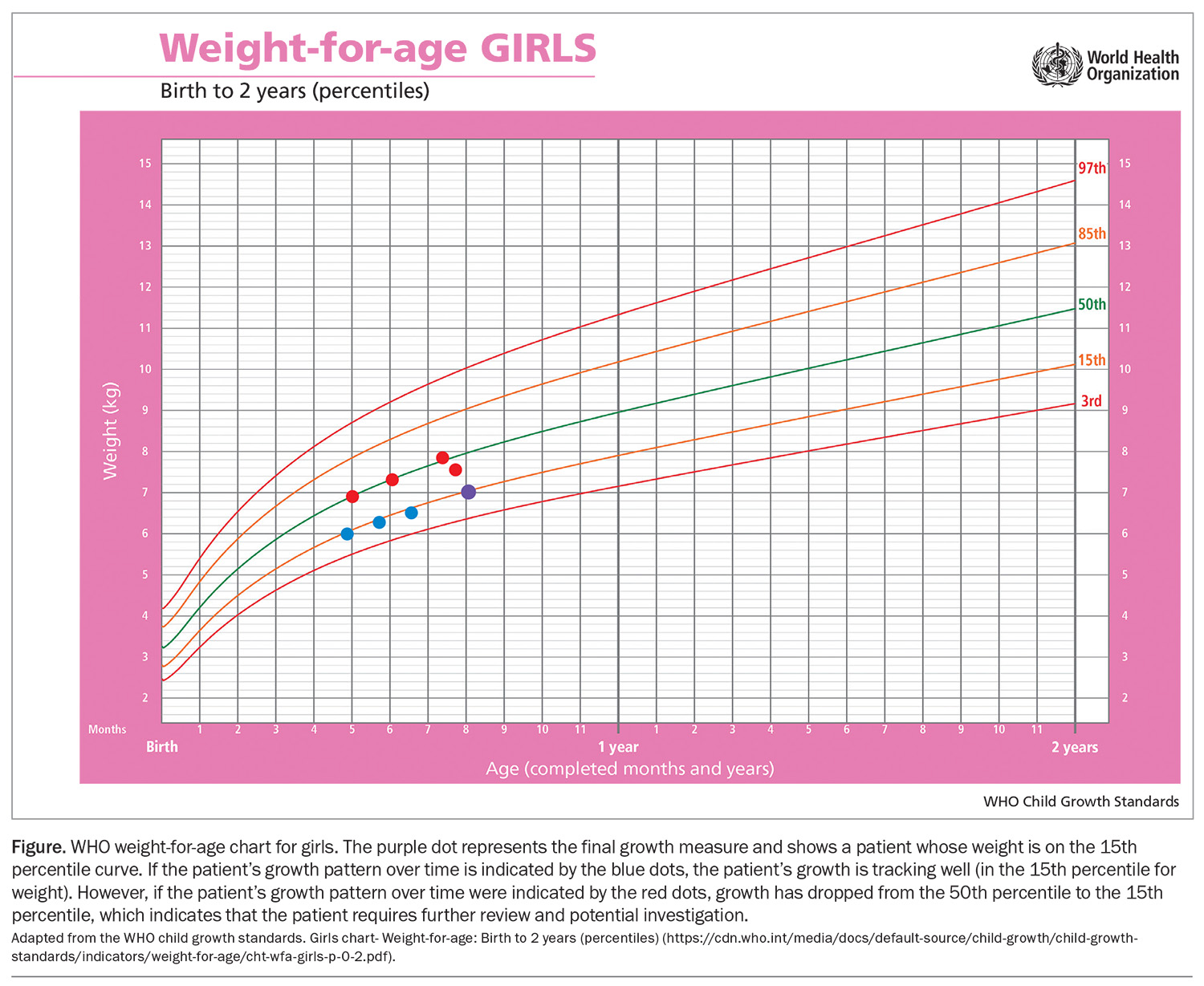

A single measure of weight, length and head circumference indicates a patient’s size but cannot be used to assess growth or to diagnose faltering growth. Collecting serial measures is essential to assessing a patient’s progress over time.4 An example of normal versus potentially concerning growth is provided in the Figure, which is based on the WHO weight-for-age growth chart for girls (https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/standards/weight-for-age). The purple dot in the Figure, representing the final growth measure, shows a patient whose weight is on the 15th percentile curve. This in itself is not indicative of the patient’s progress. However, in the context of the patient’s growth pattern over time, indicated by the blue dots, the patient’s growth is tracking well (in the 15th percentile for weight). In another scenario, if a patient’s growth pattern over time were indicated by the red dots, growth has dropped from the 50th percentile to the 15th percentile, which indicates that the patient requires further review and potentially investigation.

Assessing intake

Quantifying intake in an infant who is breastfed can be challenging, but surrogate markers of urine output and growth can indicate whether an infant is getting enough.3 Intake in a formula-fed infant is easier to quantify as parents can report intake at each feed, in addition to assessing urine output and growth. Formula-fed infants should take about 140 to 160 mL/kg of body weight in their first 3 months.5

Urine and stool output

In the first few days of life, newborn babies may have one to two wet nappies per day as their stomach is small and takes time to expand and take larger volumes. After this, babies will usually have a wet nappy after or during each feed, equating to six or more wet nappies in 24 hours.3

Stool output can vary widely in babies and is not necessarily an indicator of feeding adequacy. Frequent runny stools are not necessarily a sign of an underlying clinical issue; babies may have as many as 12 stools per day, or as few as one stool per week, and still be considered ‘normal’.

Growth

Monitoring growth in the early stages of infancy is important; however, it is important to remember that this is a time of flux both for the infant and new parents. Breastfeeding is a relationship between the mother and baby, and learning this skill together can take time. It is crucial that parents have access to support to troubleshoot feeding difficulties that may arise, which can help to maintain a positive feeding relationship beyond infancy.6 The Australian Breastfeeding Association is a useful resource that provides support and advice for parents and health professionals (https://www.breastfeeding.asn.au).

Feeding challenges in the early stages of infancy are common and most can be managed with the assistance of a maternal child and family health nurse or lactation consultant to support the developing breastfeeding relationship. Examples of feeding issues include difficulty with latching, painful latching, cracked nipples, breast engorgement or oversupply of milk, difficulty positioning for feeds, baby being unsettled, baby feeding frequently or parents’ concerns that the baby is not getting enough milk.

Parents are under pressure to ‘get it right’ with feeding, and focusing on weight can cause unnecessary stress during a time of adjustment, sleep deprivation and hormonal changes. Weekly weight measurements should be more than sufficient to observe trends in weight gain. Introducing top ups or bottle feeds can affect the developing breastfeeding relationship and, unless there are acute concerns about dehydration (reduced urine output, static weight or weight loss, sunken fontanelle), should be used with caution.7

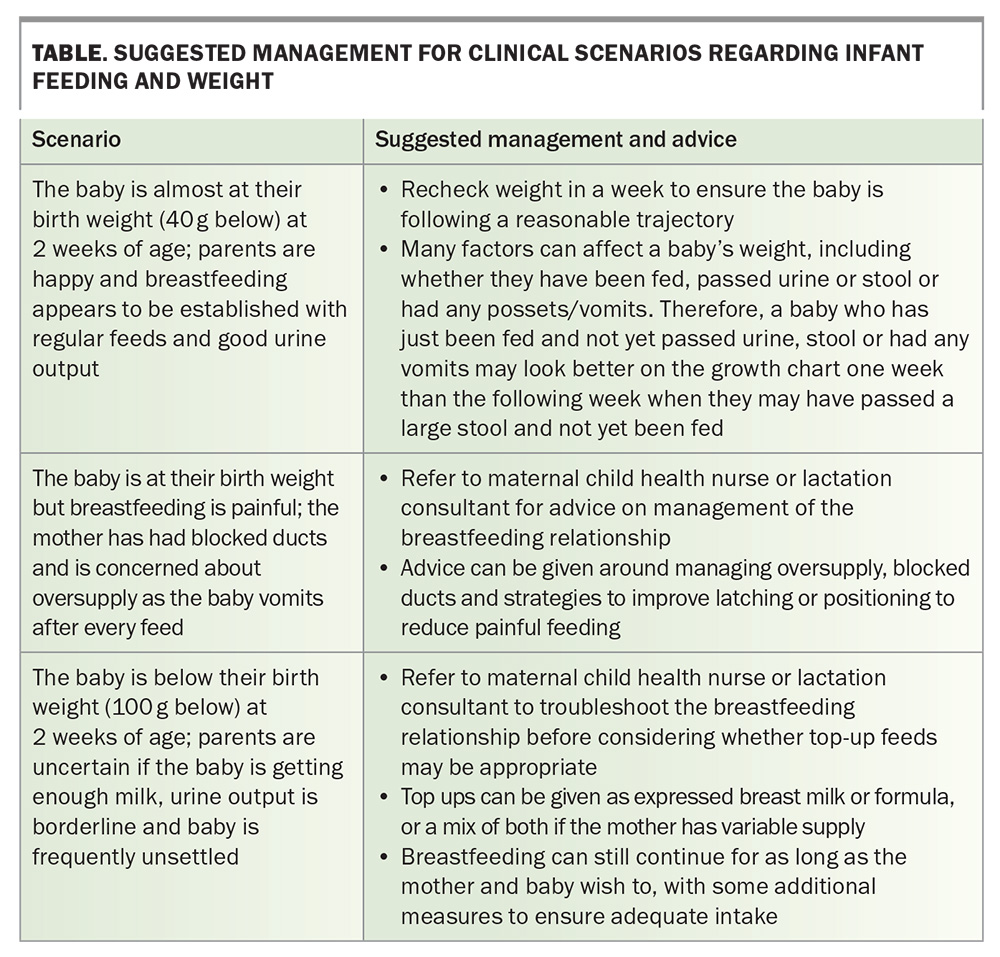

Babies often lose up to 10% of their birth weight in the first few days due to many factors, including being born with additional fluid and taking small initial volumes of colostrum before the mother’s milk comes in. This weight is usually regained by about 2 weeks of life.3 However, regaining birth weight is not the sole indicator of ‘successful’ feeding. Clinical judgement should be used before suggesting changes to the baby’s feeding.3 Potential clinical scenarios and suggested management are outlined in the Table.

Growth in the first few months

Typically, when an infant’s weight and length are plotted on the growth chart, they begin to follow on or between a percentile curve.4 Weight and length do not necessarily need to be on the same percentile for growth to be considered normal – some babies are well-covered with good fat stores, whereas others may be a little longer and leaner. Infants with a large discrepancy between weight and length may require investigation and intervention. Similarly, a baby with decreasing weight percentiles will require ongoing review of their progress and, usually, investigation and intervention.

Referral to a maternal child health nurse or a paediatric dietitian can help with quantifying intake, assessing feeding behaviours and discussing parental concerns. Realistically, these professionals will have more time available in an appointment than the length of a standard GP consult, and have sufficient depth of experience to be able to assess where a patient’s intake lies in the spectrum of ‘normal’. In addition, they can give guidance on the need for top ups (either with expressed breast milk or formula) and fortifying feeds, as well as advice around introducing solids and enriching these with energy- and protein-dense foods or additives.

Further investigation may be required in some cases. For example, patients with inadequate intake and faltering growth despite the use of fortification strategies should be considered for gastroenterological investigations for malabsorption, or endocrine investigations for hormonal influences on growth.

Introducing top-up feeds

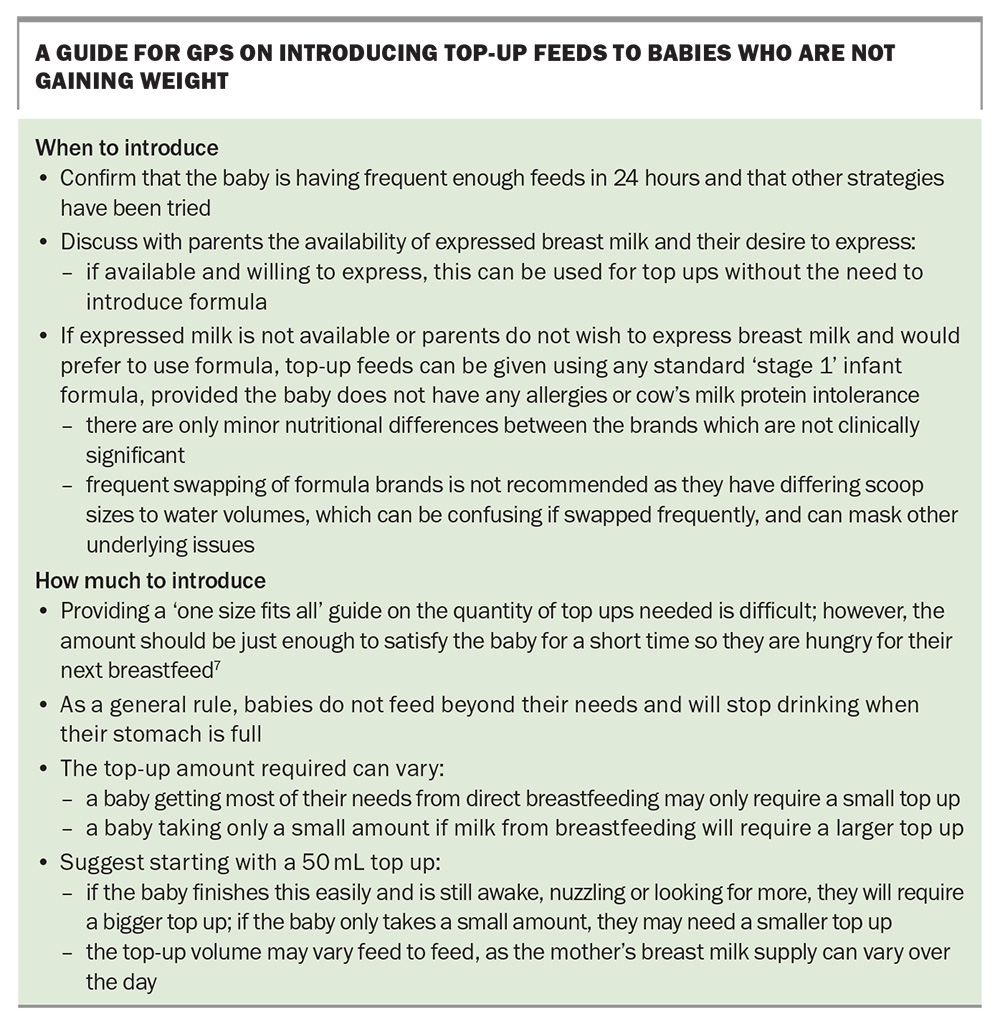

In an ideal scenario, GPs should have ready access to multidisciplinary supports. However, if a baby needs top-up feeds and no additional health professionals are available (such as in a rural practice setting), the GP may need to help parents introduce these. GPs should first confirm with parents the baby's feeding frequency over 24 hours and that other strategies have been tried before discussing top ups. Such strategies include:

- allowing the baby to go for a little longer between feeds to build up hunger and see if this improves their intake if feeding frequently

- offering the baby more frequent feeds if feeding less frequently

- changing the baby’s nappy halfway through a feed to wake them up if they have fallen asleep and encourage intake after this

- burping the baby to allow them to maximise intake and minimise discomfort

- ensuring that latch has been effective and not painful

- utilising a variety of feeding positions if needed.

The top-up amount will depend on how much the baby is taking directly from breastfeeding and should be just enough to satisfy the baby for a short time so they are hungry for their next breastfeed.7 Guidance on introducing top-up feeds to babies who are not gaining weight is outlined in the Box. In babies given formula top ups, frequent swapping of formula brands is not recommended as the different preparations between brands can be confusing and formula incorrectly made up. Additionally, in babies experiencing issues with formula, swapping formulas may mask the true issue (e.g. if a baby has cow’s milk protein intolerance, swapping between several cow’s milk based formulas is not going to resolve this problem).

Cow’s milk protein intolerance

Cow’s milk protein intolerance is not an indication to stop breastfeeding. Babies with cow’s milk protein intolerance can continue to be breastfed if maternal exclusion of cow’s milk products is achievable. Referring the mother to a dietitian may be helpful for dietary guidance and assessment of nutritional adequacy. The Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy provides information on dietary exclusion (www.allergy.org.au), as well as guidance on appropriate formula alternatives if the maternal exclusion diet cannot be achieved or the mother chooses not to continue breastfeeding (https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/papers-guide- for-milk-substitutes-cows-milk-allergy).

Monitoring progress

Monitoring growth over time provides the most information on the requirement for ongoing top-up feeds. If a baby demonstrates ‘catch-up’ growth, top ups may be reduced gradually, or weaned altogether.8 As breastfeeding becomes more efficient and effective, the baby may naturally reduce the amount they take from a top up.8 Top ups can be continued if a baby seems to have an ongoing need. The baby can be mix-fed for as long as needed, and this may be the best balance for the mother and baby.

It is important to regularly review progress and the practicality of continuing top ups, particularly if the mother is expressing frequently through the day and night, as this can be exhausting and, for many mothers, unsustainable over long periods of time. Monitoring patients over time can be time-intensive, may require frequent reviews and is best done with ongoing multidisciplinary input for feeding advice.

When to change to formula feeding

A conversation to should be had with parents about switching to formula if the mother has decided she wishes to stop breastfeeding; is exhausted with breastfeeding, top ups or expressing; or has come to the end of her breastfeeding journey. There are no nutritional advantages between different brands of ‘stage 1’ cows’ milk-based infant formula; hence, parents can make a choice based on personal preference, availability and budget. Switching from breast milk to formula can be an emotional decision; therefore, it is important for parents to feel supported in their decision making and for clinicians to acknowledge that formula feeding is safe and appropriate, meets the baby’s nutritional needs and will continue to develop bonding between parents and their baby.

Conclusion

GPs have an important role in supporting parents in their infant feeding journey, and are often the first healthcare professional parents turn to for advice. Multidisciplinary support can assist GPs in managing parental growth and feeding concerns. It is important that feeding strategies consider the infant’s whole clinical picture, and are practical and sustainable for families. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. de Onis M. 4.1 The WHO Child Growth Standards. World Rev Nutr Diet 2015; 113: 278-294.

2. de Onis M, Garza C, Victora CG, Bhan MK, Norum KR. The WHO multicentre growth reference study (MGRS): rationale, planning, and implementation. Food Nutr Bull 2004; 25 (Suppl): S1-S89.

3. National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Infant feeding guidelines: information for health workers. 2012. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing: Canberra, 2012. Available online at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/n56 (accessed April 2024).

4. A health professional’s guide for using the new WHO growth charts. Paediatr Child Health 2010; 15: 84-98.

5. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. Oria M, Harrison M, Stallings VA (eds). Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2019.

6. Australian Breastfeeding Association. Breastfeeding: how will it look over time? Australian Breastfeeding Association: Melbourne; 2022. Available online at: https://www.breastfeeding.asn.au/resources/breastfeeding-how-will-it-look-over-time (accessed April 2024).

7. Australian Breastfeeding Association. Does my baby really need a top-up? Australian Breastfeeding Association: Melbourne; 2023. Available online at: https://www.breastfeeding.asn.au/resources/does-baby-need-top-up (accessed April 2024).

8. Australian Breastfeeding Association. How to stop the formula top-ups. Australian Breastfeeding Association: Melbourne; 2022. Available online at: https://www.breastfeeding.asn.au/resources/stop-formula-top-ups (accessed April 2024).