Micronutrient supplementation – supporting a healthy pregnancy and baby

GPs play an important role in providing guidance on appropriate nutrient supplement use for women before and during pregnancy and while breastfeeding. Micronutrient supplement use by these women lowers their risk of some adverse pregnancy health outcomes and supports the growth of the developing baby.

- Key opportunities to discuss nutrient supplements with women are at the preconception visit, first antenatal visit and first postnatal visit.

- Although most pregnant women are aware of the need for nutrient supplements in pregnancy, there are much lower levels of specific knowledge of the recommended nutrients and their dose and timing.

- Some multinutrient pregnancy-specific supplements do not contain the recommended combination of micronutrients or doses for all women (without additional nutrient needs) before and during pregnancy, or while breastfeeding.

- Only folic acid and iodine supplements are recommended for all women before and during pregnancy. Iodine supplementation should be continued while breastfeeding.

- Other nutrient supplements, such as iron, calcium, vitamin B12, vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids, may also be recommended depending on a woman’s individual needs, dietary deficiencies and health.

- Screen for iron-deficiency anaemia routinely at the first antenatal visit and at 28 weeks’ gestation to determine if iron supplementation is required.

Micronutrients have important influences on the health of pregnant women and their children, including lowering the risk of some adverse pregnancy health outcomes and supporting the growth of the developing baby.1 The recommended dietary intake for micronutrients, such as folate and iodine, is higher during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding.2 Normal eating habits and the fortification of foods in Australia usually do not meet these increased nutrient needs.3-5 Therefore, supplementation for some nutrients is recommended to support a healthy pregnancy and baby.6,7

In Australia, GPs are important providers of preconception, antenatal and postnatal care for women. Between 85 and 92% of women of reproductive age (15 to 44 years) report seeing a GP in the previous 12 months, and between 6 and 17% specifically seek care from their GP for preconception or family planning support.8 GPs also provide antenatal care to almost 90% of women in early pregnancy and to 28% throughout their pregnancy.9 For most pregnant women, GPs are the first point of health care contact,10 including for the 40% of women who experience an unplanned pregnancy.11 GPs are integral providers of advice and support for nutrient supplement use for women who are planning a pregnancy, during pregnancy and while breastfeeding. However, Australian healthcare providers, including GPs, report barriers to providing such care, including uncertainty as to whether supplementation is needed when there is mandatory food fortification (e.g. for folate and iodine) in Australia, and lack of knowledge on what to recommend, including the appropriate dose and duration, and additional considerations required for individualised recommendations.12,13

Studies of GP provision of nutrient supplements for women during pregnancy and breastfeeding report highly variable findings. In three studies that included a total of 142 GPs in Australia, 52% reported recommending folic acid supplements to pregnant women, 66% reported recommending iodine supplements to women planning a pregnancy,26 to 84% to women during pregnancy and 45% to women who are breastfeeding.13-15

This article provides an overview of the latest evidence and clinical practice guidelines to support GPs in providing recommendations on nutrient supplements to women before and during pregnancy and while breastfeeding.

What proportion of women use nutrient supplements before and during pregnancy and while breastfeeding?

In Australia, nutrient supplement use during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding is highly variable. Although most pregnant women are aware of the need for nutrient supplements in pregnancy, there are much lower levels of specific knowledge of the recommended nutrients, their dose and timing.16 Adherence to the recommendations is also low.16 Although one in three pregnant women in Australia report taking a multinutrient supplement (containing one or more micronutrients),17 these may not provide the recommended nutrients or doses required for the particular stage of pregnancy or in the context of diagnosed health conditions and nutrient deficiencies.18

In the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health, self-reported data on nutritional supplement use in 485 women of reproductive age was recorded prospectively.19 Before conceiving, about half of the women who later became pregnant reported taking a folic acid-containing supplement and 37% took an iodine-containing supplement.19 Although up to 39% took an iron- containing supplement prior to pregnancy, only 23% reported having a diagnosed iron deficiency,19 which may indicate a need for iron supplementation.6,20

During pregnancy, about nine out of ten women in Australia report taking a folic acid-containing supplement, and eight out of ten take an iodine-containing supplement.16,21 Other supplements often consumed in pregnancy include iron (30%), vitamin D (23%), calcium (13%) and fish oil/omega-3 fatty acids (12%), although it is unclear if supplementation was recommended based on a diagnosed nutrient deficiency, dietary pattern or clinical indication.22

During breastfeeding, 45% of women in Australia report taking an iodine-containing supplement.23 Of concern, many women who took iodine supplements during pregnancy ceased taking supplements when breastfeeding.23 Most women who continue to take nutrient supplements while breastfeeding report consuming a multivitamin that contributes only half the recommended dose of iodine.23

Adherence to the correct dose and duration of supplements across preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding is low. In a 2013 Australian study of 857 women, only one in five fully adhered to recommendations on both the dose and duration of folic acid and iodine supplementation specific to the stage of pregnancy.16 Women who were aware of the recommended duration of supplements and who planned their pregnancy were more likely to adhere to the recommendations.16

There is limited information on the use of nutrient supplements among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. This may be a consequence of not including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in designing and conducting research which could ensure that culturally appropriate research methods are used.24-26 In a 2014-19 cohort study of 152 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander pregnant women or pregnant women carrying an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander baby in rural NSW, 51% of women reported taking a folic acid supplement during pregnancy.27 Barriers to accessing health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, including historical trauma arising from colonisation, systemic racism and socioeconomic disadvantage, are well documented.28 These factors, along with cost and access to nutrient supplements, may contribute to lower rates of supplement use by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.28 General multinutrient supplements may be chosen by women over pregnancy-specific nutrient supplements due to concerns about cost; however, these general multinutrient supplements often have insufficient quantities of nutrients recommended for pregnancy.29

About 90% of pregnant women in Australia want support and advice from their healthcare providers, including their GPs, on which nutrient supplements are required for a healthy pregnancy and while breastfeeding.16,21,30 Of concern, women often report seeking advice on supplements from the internet; however, over 40% of websites with information on pregnancy nutrient supplements have been shown to be inaccurate or misleading.31 Systematic review evidence shows that advice and support from healthcare providers, including GPs, during the preconception and antenatal periods improves women’s adherence to nutrient supplement recommendations.32,33

What are the impacts of nutrient supplements on the pregnancy, mother and child?

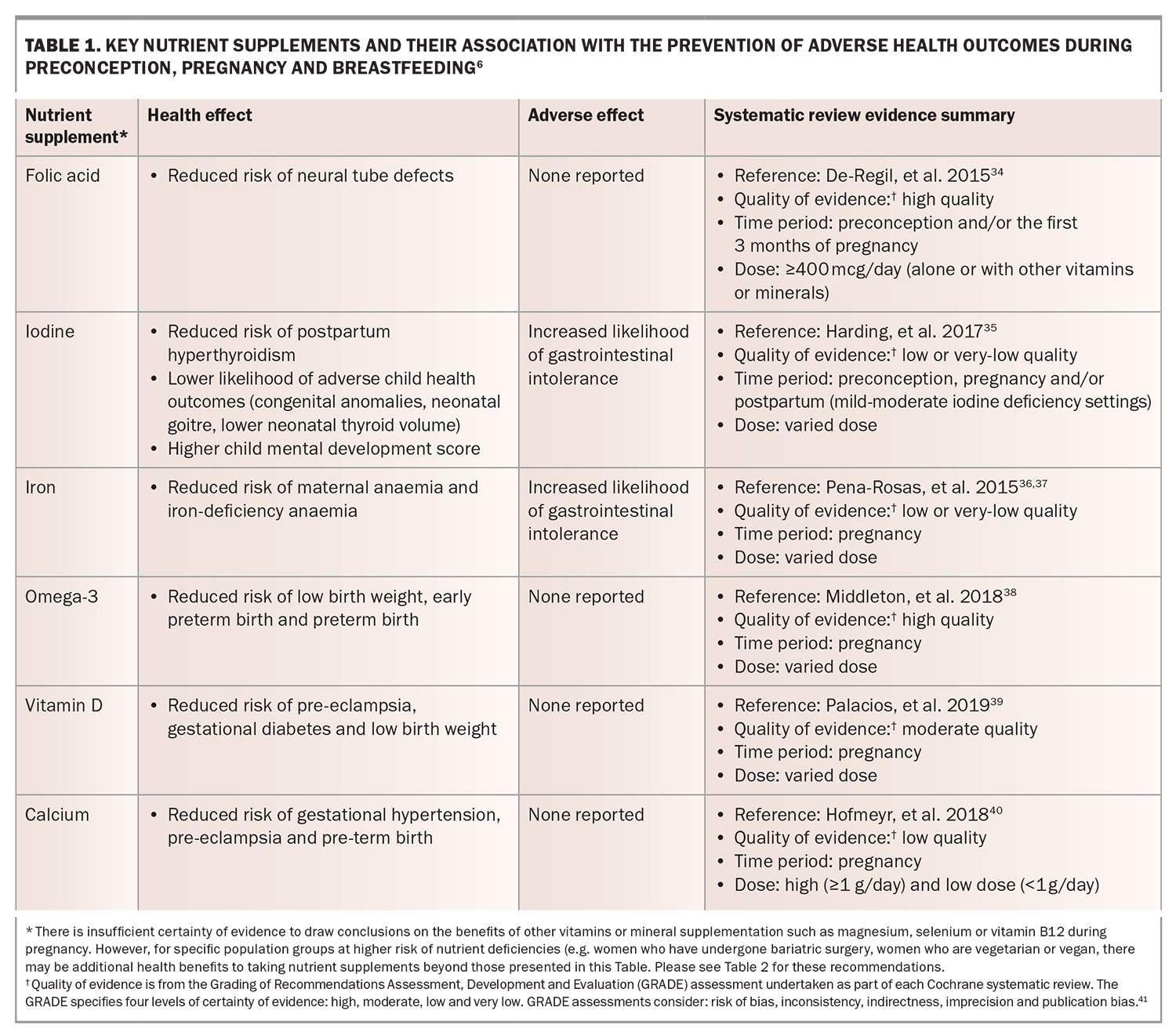

Supplementation of some nutrients (e.g. folic acid and iodine) before conception, during pregnancy and while breastfeeding is associated with a range of positive pregnancy and health outcomes. In the absence of a diagnosed deficiency or medical need, the current available evidence suggests that other nutrient supplements provide no benefit and may have adverse consequences. Evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the association between supplementation of key micronutrients and positive health outcomes during preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding is summarised in Table 1.34-41

The association between micronutrients and other pregnancy and health outcomes has recently been investigated. For example, emerging research has examined the association between vitamin D deficiency and autism spectrum disorders.42-45 The current evidence base is primarily from animal studies or observational studies in humans with small sample sizes with inconsistent evidence of an association or causal relationship.42-45 Currently, there is insufficient evidence to recommend vitamin D supplements to all pregnant women to reduce the risk of autism spectrum disorders in children.45

What nutrient supplements are recommended?

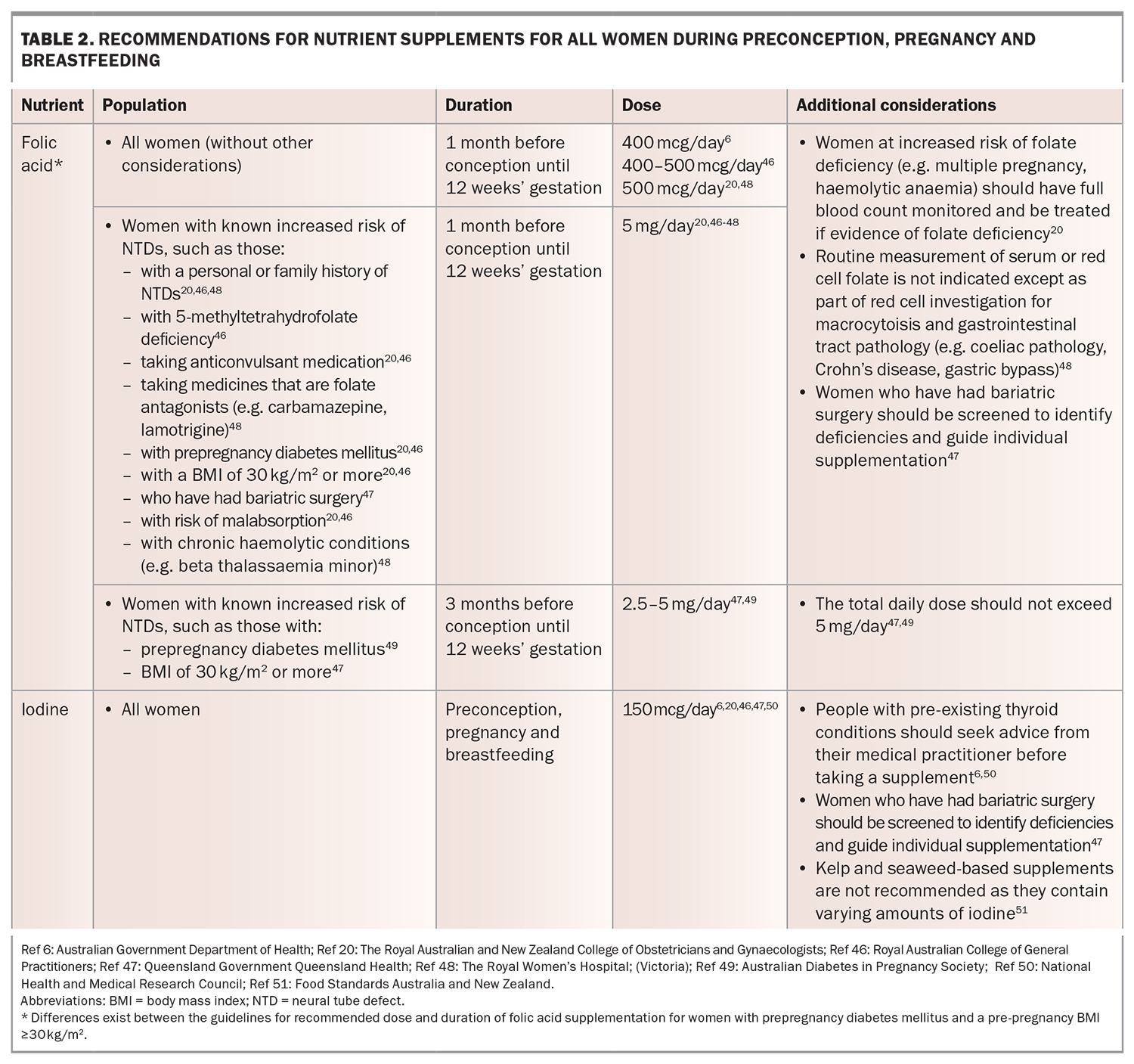

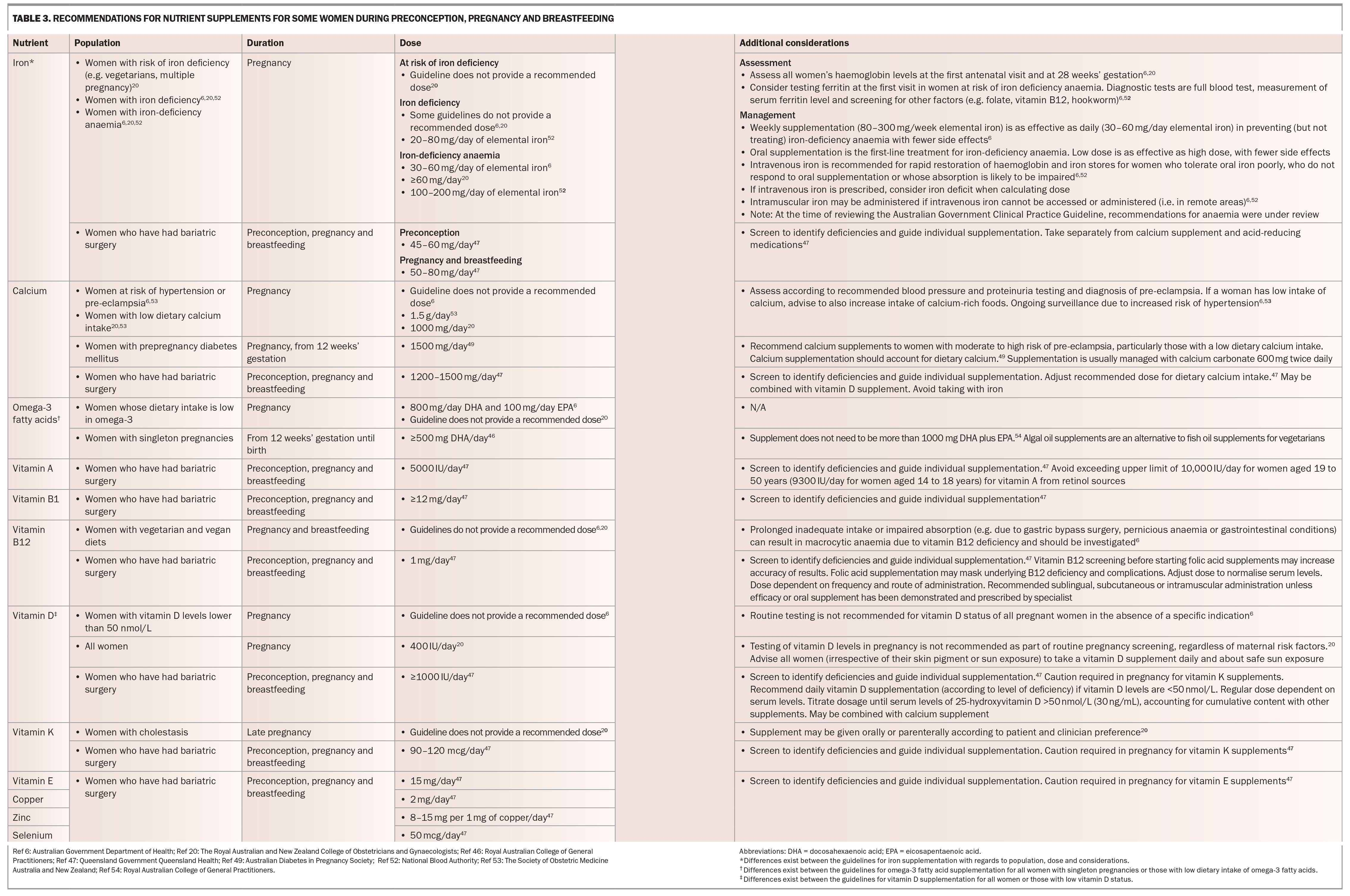

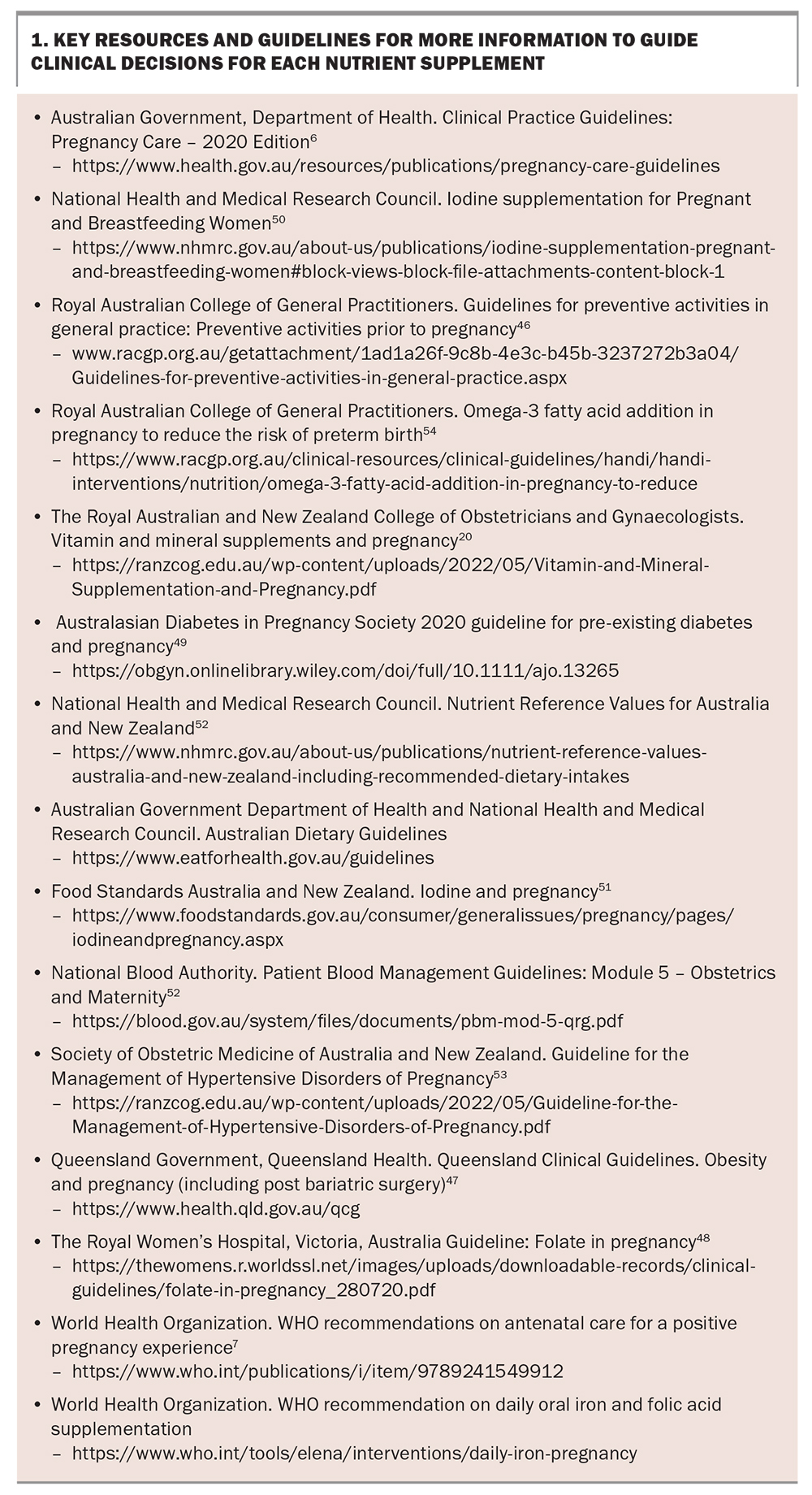

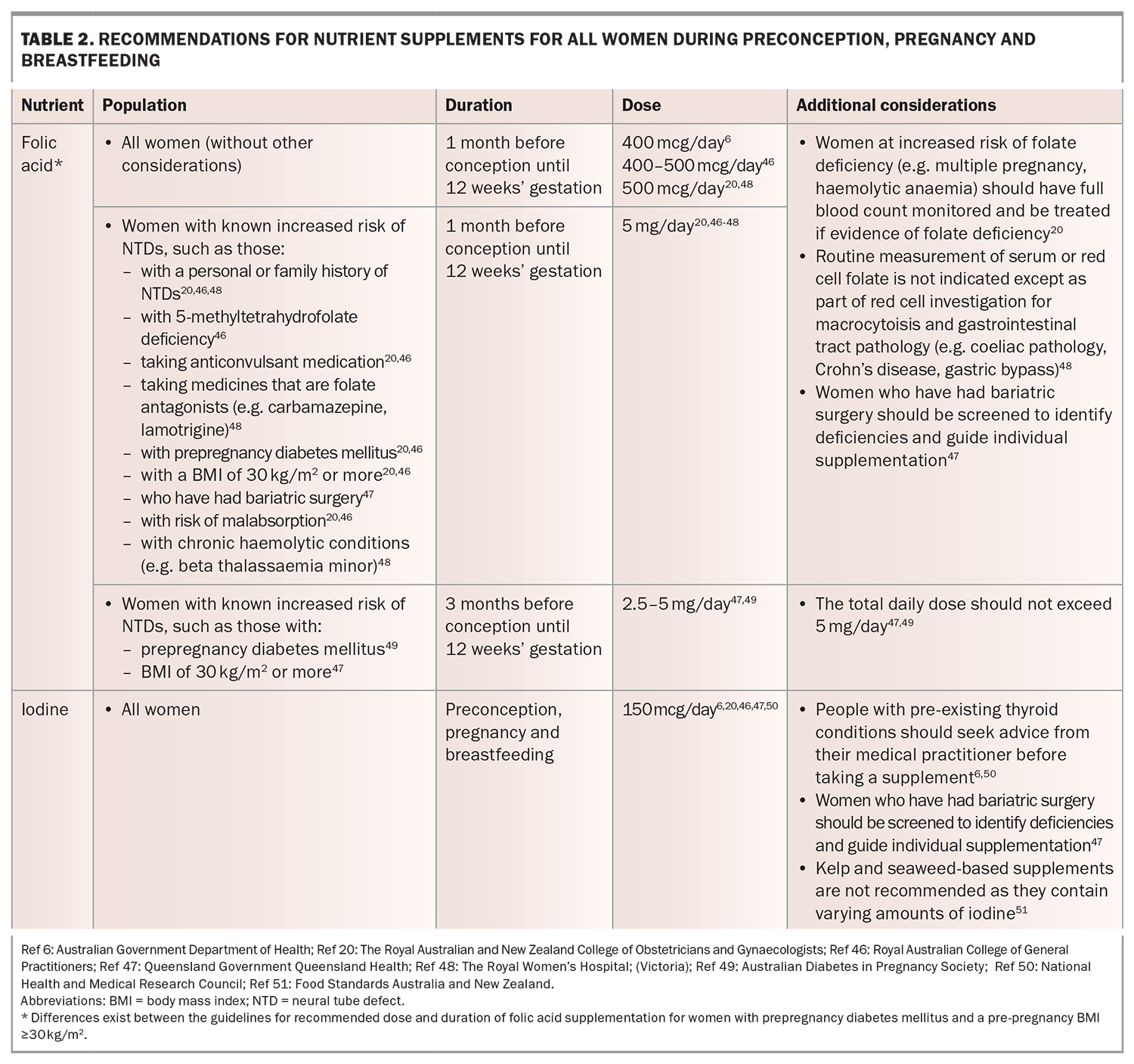

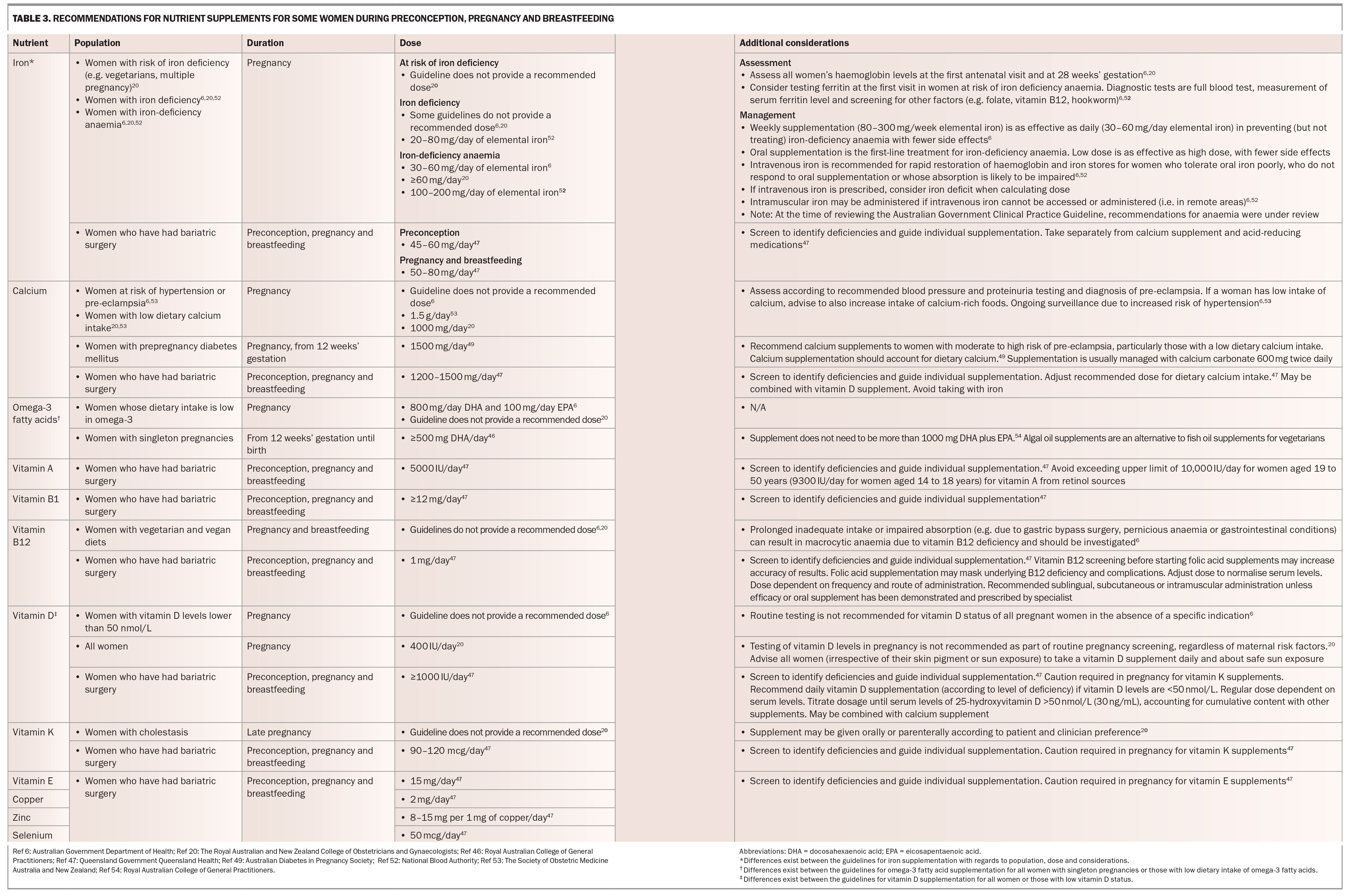

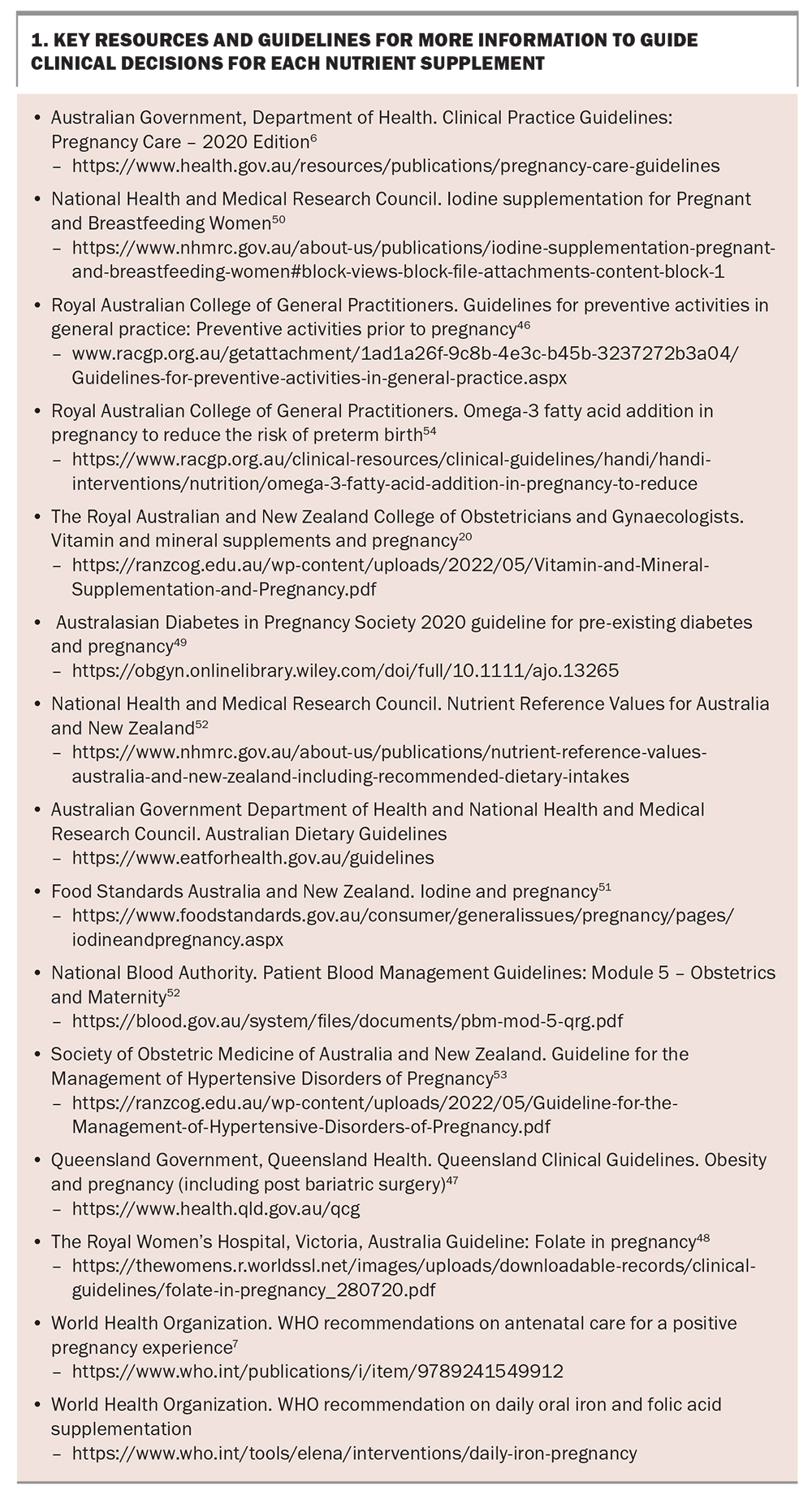

The Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care, The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (as well as other Australian state, hospital and medical body guidelines) recommend folic acid and iodine supplementation for all women who are planning a pregnancy or are pregnant, and iodine supplementation for breastfeeding women (Table 2).6,20,46-51 Other nutrient supplements, such as iron, calcium, vitamin B12, vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acids, may also be recommended depending on a woman’s individual needs, dietary deficiencies and health.6,20,47 In the absence of a diagnosed deficiency, nutrient supplements of vitamin A, C and E are not recommended because they provide little or no benefit and may have adverse health consequences.6,20 The specific populations for whom additional nutrient supplements are recommended according to key national, state, hospital and medical/professional body guidelines are included in Table 3.6,20,46,47,49,52-54 Some guidelines currently differ with regards to recommendations for dose, duration, routine screening and populations for whom nutrient supplementation are recommended. Possible reasons for these differences are that guidelines may not have been updated to reflect the most recent evidence, low- or varying-quality evidence has been interpreted differently and clinical judgement has been used when interpreting the evidence or contextualising to the Australian population. Some guidelines also do not cover all preconception, pregnancy and breastfeeding periods. The full list of guidelines reviewed for this article are included in Box 1 and provide more information on recommended assessment, management and monitoring for each nutrient supplement.

Many women take multinutrient supplement(s) before or early in pregnancy and although these supplements contain many of the individual vitamins and minerals presented in Table 2 and Table 3, the dose may be insufficient or exceed nutrient supplement recommendations.18 It is important to ask what nutrient supplements (including the brand, dose and timing) the women is already taking or planning to take in pregnancy, to inform the provision of advice on nutrient supplementation.6

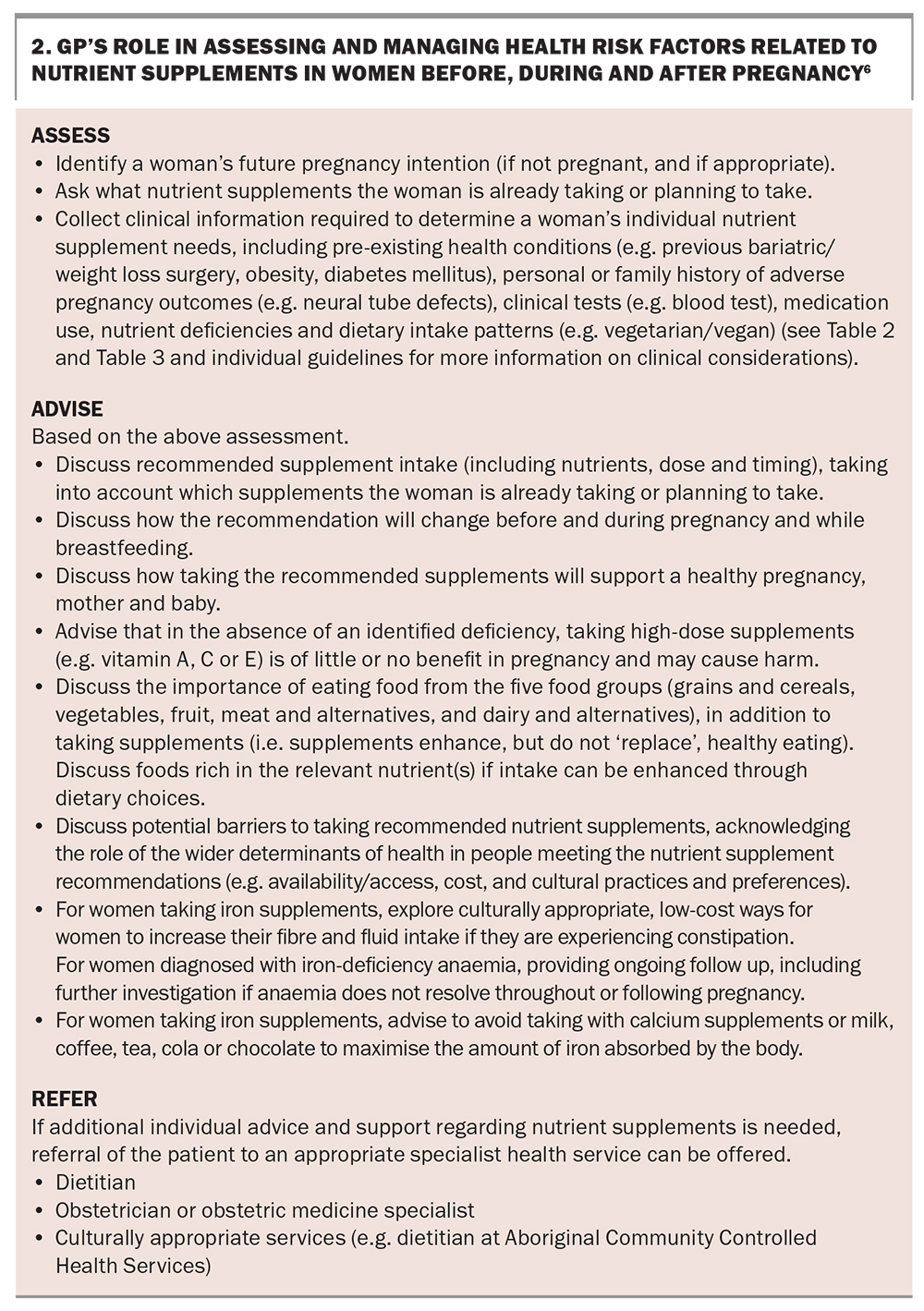

What is the GP’s role in supporting women to take nutrient supplements?

The Australian Department of Health Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pregnancy recommend the following three elements of care to support women to take nutrient supplements (Box 2).6

- Assess current nutrient supplement intake and any health and dietary considerations required to guide clinical decisions on individualised recommendations.

- Advise and discuss recommended nutrient supplements and benefits for the pregnancy and baby.

- Refer to a specialist, such as a dietitian, obstetrician or obstetric medicine specialist, if further advice and support is needed.

In the primary care setting, a collaborative conversation that invites the views of a patient, with tailored discussions based on question-answer sequences and joint decision-making when planning actions to overcome barriers, is more likely to lead to patient behaviour change compared with advice-giving only.55 Pregnant women commonly cite forgetting to take supplements and not knowing the recommended type, dose and timing of nutrient supplements required (or which supplement brand types provide their nutrient requirements) as barriers to adhering to supplement recommendations.21,56 Supporting women to identify their personal barriers to supplement use and checking that they have correctly understood what is being recommended (including the dose, timing, frequency and duration of therapy) may support adherence.

Conclusion

GPs play an important role in providing guidance on appropriate nutrient supplement use for women before and during pregnancy and while breastfeeding. Nutrient supplement use around the pregnancy life stage is effective in optimising health outcomes for pregnant women and their babies. Recommendations for universal and selective supplementation are included in a range of resources (Box 1), but management needs to consider the woman’s nutritional and health status and be individualised and based on clinical judgement.

Further considerations

In this article, we refer to pregnant ‘women’ to reflect research evidence, while acknowledging that transgender and gender-diverse people can also become pregnant. Engaging with partners and families is important in supporting women to meet their nutrient supplement needs and should be considered when providing care. This article summarises current recommendations on nutrient supplements from a range of national, state, hospital and medical/professional body guidelines at the time of writing the article. Other guidelines with nutrient supplement recommendations may exist and should be considered where clinically and locally relevant. Recommended care for dietary food intake, including the five food groups, probiotics, food safety and weight during pregnancy57 are outside the scope of this article and will be summarised in other articles in Medicine Today. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Hollis is a Clinical and Health Service Research Fellow funded by Hunter New England Local Health District Partnerships, Innovation and Research through the HNELHD Clinical and Health Service Research Fellowship Scheme. Associate Professor de Jersey is an Associate Professor in the Centre for Health Services Research at the University of Queensland funded through the Metro North Health Clinician Research Fellowship Scheme. Professor Elliott was supported by a Medical Research Futures Fund Next Generation Fellowship (APP1135959) and a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Leadership Fellowship (No 2026176). Dr Kingsland is Research Fellow with the University of Newcastle funded through a grant from The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre (TAPPC) and a Program Manager with Hunter New England Population Health. Dr Cannon, Dr Kimura, Dr Guppy, Dr Delaney: None.

References

1. Marshall NE, Abrams B, Barbour LA, et al. The importance of nutrition in pregnancy and lactation: lifelong consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2021; 226: 607-632.

2. National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, New Zealand Ministry of Health. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2006.

3. Hure A, Young A, Smith R, Collins C. Diet and pregnancy status in Australian women. Public Health Nutr 2009; 12: 853-861.

4. Wilkinson SA, Schoenaker DA, de Jersey S, et al. Exploring the diets of mothers and their partners during pregnancy: findings from the Queensland Family Cohort pilot study. Nutr Diet 2022;(5): 602-615.

5. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Monitoring the health impacts of mandatory folic acid and iodine fortification. Canberra: AIHW; 2016.

6. Australian Government, Department of Health. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pregnancy Care - 2020 Edition. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2020.

7. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience: WHO; 2016.

8. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Health service usage and health related actions, Australia (2014-15). ABS Cat. no. 4364.0.55.002. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2017. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Lookup/4364.0.55.002Main+Features12014-15 (accessed February 2024).

9. Brown SJ, Sutherland GA, Gunn JM, Yelland JS. Changing models of public antenatal care in Australia: is current practice meeting the needs of vulnerable populations? Midwifery 2014; 30: 303-309.

10. Prosser S, Miller Y, Armanasco A, Hennegan J, Porter J, Thompson R. Findings from the having a baby in Queensland survey, 2012. Brisbane. Australia: Queensland Centre for Mothers & Babies, University of Queensland; 2013. Available online at: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/117936/1/HABIQ-20-Survey-2020-1220-Final20-Report202.pdf (accessed February 2024).

11. Rowe H, Holton S, Kirkman M, et al. Prevalence and distribution of unintended pregnancy: the Understanding Fertility Management in Australia National Survey. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016; 40: 104-109.

12. Lucas C, Charlton KE, Yeatman H. Nutrition advice during pregnancy: do women receive it and can health professionals provide it? Matern Child Health J 2014; 18: 2465-2478.

13. Guess K, Malek L, Anderson A, Makrides M, Zhou SJ. Knowledge and practices regarding iodine supplementation: A national survey of healthcare providers. Women Birth 2017; 30: e56-e60.

14. Hughes R, Maher J, Baillie E, Shelton D. Nutrition and physical activity guidance for women in the pre- and post-natal period: a continuing education needs assessment in primary health care. Aust J Prim Health 2011; 17: 135-141.

15. Lucas CJ, Charlton KE, Brown L, Brock E, Cummins L. Antenatal shared care: are pregnant women being adequately informed about iodine and nutritional supplementation? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2014; 54: 515-521.

16. Malek L, Umberger W, Makrides M, Zhou SJ. Poor adherence to folic acid and iodine supplement recommendations in preconception and pregnancy: a cross‐sectional analysis. Aust N Z J Public Health 2016; 40: 424-429.

17. Forster DA, Wills G, Denning A, Bolger M. The use of folic acid and other vitamins before and during pregnancy in a group of women in Melbourne, Australia. Midwifery 2009; 25: 134-146.

18. Wilson RL, Gummow JA, McAninch D, Bianco‐Miotto T, Roberts CT. Vitamin and mineral supplementation in pregnancy: evidence to practice. J Pharm Pract Rese 2018; 48: 186-192.

19. McKenna E, Hure A, Perkins A, Gresham E. Dietary supplement use during preconception: The Australian Longitudinal study on Women’s Health. Nutrients 2017; 9: 1119.

20. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Vitamin and mineral supplementation and pregnancy; 2019. Available online at: https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Vitamin-and-Mineral-Supplementation-and-Pregnancy.pdf (accessed February 2024).

21. Malek L, Umberger WJ, Makrides M, Collins CT, Zhou SJ. Understanding motivations for dietary supplementation during pregnancy: A focus group study. Midwifery 2018; 57: 59-68.

22. Shand AW, Walls M, Chatterjee R, Nassar N, Khambalia AZ. Dietary vitamin, mineral and herbal supplement use: a cross‐sectional survey of before and during pregnancy use in Sydney, Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2016; 56: 154-161.

23. Axford S, Charlton K, Yeatman H, Ma G. Poor knowledge and dietary practices related to iodine in breastfeeding mothers a year after introduction of mandatory fortification. Nutr Diet 2012; 69: 91-94.

24. Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, et al. Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: the CONSIDER statement. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019; 19: 1-9.

25. Harfield S, Pearson O, Morey K, et al. Assessing the quality of health research from an Indigenous perspective: the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander quality appraisal tool. BMC Med Res Methodol 2020; 20: 1-9.

26. Jamieson LM, Paradies YC, Eades S, et al. Ten principles relevant to health research among Indigenous Australian populations. Med J Aust 2012; 197: 16-18.

27. Beringer M, Schumacher T, Keogh L, et al. Nutritional adequacy and the role of supplements in the diets of Indigenous Australian women during pregnancy. Midwifery 2021; 93: 102886.

28. Baker EA, Ramirez LKB, Claus JM, Land G. Translating and disseminating research-and practice-based criteria to support evidence-based intervention planning. J Public Health Manag Pract 2008; 14: 124-130.

29. Livock M, Anderson PJ, Lewis S, Bowden S, Muggli E, Halliday J. Maternal micronutrient consumption periconceptionally and during pregnancy: a prospective cohort study. Public Health Nutr 2017; 20: 294-304.

30. Bryant J, Waller AE, Cameron EC, Sanson-Fisher RW, Hure AJ. Receipt of information about diet by pregnant women: A cross-sectional study. Women Birth 2019; 32: e501-e7.

31. Lobo S, Lucas CJ, Herbert JS, et al. Nutrition information in pregnancy: Where do women seek advice and has this changed over time? Nutr Diet 2020; 77: 382-391.

32. Withanage NN, Botfield JR, Srinivasan S, Black KI, Mazza D. Effectiveness of preconception interventions in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2022; 72: e865-e872.

33. Gomes F, King SE, Dallmann D, et al. Interventions to increase adherence to micronutrient supplementation during pregnancy: a systematic review. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2021; 1493: 41-58.

34. De‐Regil LM, Peña‐Rosas JP, Fernández‐Gaxiola AC, Rayco-Solon P. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(12): CD007950.

35. Harding KB, Peña‐Rosas JP, Webster AC, et al. Iodine supplementation for women during the preconception, pregnancy and postpartum period. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017(3): CD011761.

36. Peña‐Rosas JP, De‐Regil LM, Garcia‐Casal MN, Dowswell T. Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(7): CD004736.

37. Peña‐Rosas JP, De‐Regil LM, Malave HG, Flores‐Urrutia MC, Dowswell T. Intermittent oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(10): CD009997.

38. Middleton P, Gomersall JC, Gould JF, Shepherd E, Olsen SF, Makrides M. Omega‐3 fatty acid addition during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018(11): CD0003402.

39. Palacios C, Kostiuk LK, Peña‐Rosas JP. Vitamin D supplementation for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019(7): CD008873.

40. Hofmeyr GJ, Lawrie TA, Atallah ÁN, Torloni MR. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018(10): CD001059.

41. Higgins JPT Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023): Cochrane; 2023. Available online at: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed February 2024).

42. Wang Z, Ding R, Wang J. The association between vitamin D status and autism spectrum disorder (ASD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2020; 13: 86.

43. Madley-Dowd P, Dardani C, Wootton RE, et al. Maternal vitamin D during pregnancy and offspring autism and autism-associated traits: a prospective cohort study. Molecular Autism 2022; 13: 44.

44. Aagaard K, Jepsen JRM, Sevelsted A, et al. High-dose vitamin D3 supplementation in pregnancy and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders in the children at age 10: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2024; 119: 362-370.

45. Principi N, Esposito S. Vitamin D deficiency during pregnancy and autism spectrum disorders development. Front Psychiatry 2020; 10: 987.

46. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2021. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/getattachment/1ad1a26f-9c8b-4e3c-b45b-3237272b3a04/Guidelines-for-preventive-activities-in-general-practice.aspx (accessed February 2024).

47. Queensland Clinical Guidelines. Obesity and pregnancy (including post bariatric surgery). Guideline No. MN21.14-V6-R26. 2021. Available online at: http://www.health.qld.gov.au/qcg (accessed February 2024).

48. The Royal Women’s Hospital. Guideline: Folate in Pregnancy Victoria, Australia2020 Available online at: https://thewomens.r.worldssl.net/images/uploads/downloadable-records/clinical-guidelines/folate-in-pregnancy_280720.pdf (accessed February 2024).

49. Rudland VL, Price SA, Hughes R, et al. ADIPS 2020 guideline for pre‐existing diabetes and pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020; 60: E18-E52.

50. National Health and Medical Research Council. Statement: Iodine Supplementation for Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women 2010. Available online at: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/iodine-supplementation-pregnant-and-breastfeeding-women#block-views-block-file-attachments-content-block-1 (accessed February 2024).

51. Food Standards Australia and New Zealand. Iodine and pregnancy 2016. Available online at: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/generalissues/pregnancy/pages/iodineandpregnancy.aspx (accessed February 2024).

52. National Blood Authority (NBA). Patient Blood Management Guidelines: Module 5 - Obstetrics and Maternity. Canberra: NBA; 2015 [Available from: https://www.blood.gov.au/system/files/documents/pbm-mod-5-qrg.pdf (accessed February 2024).

53. Lowe S, Bowyer L, Lust K, et al. Guideline for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy 2014 Available online at: https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Guideline-for-the-Management-of-Hypertensive-Disorders-of-Pregnancy.pdf (accessed February 2024).

54. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Omega-3 fatty acid addition in pregnancy to reduce the risk of preterm birth: RACGP; 2019 Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/handi/handi-interventions/nutrition/omega-3-fatty-acid-addition-in-pregnancy-to-reduce (accessed February 2024)..

55. Albury C, Hall A, Syed A, et al. Communication practices for delivering health behaviour change conversations in primary care: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMC Fam Pract 2019; 20: 1-13.

56. Kandel P, Lim S, Pirotta S, Skouteris H, Moran LJ, Hill B. Enablers and barriers to women’s lifestyle behavior change during the preconception period: A systematic review. Obes Rev 2021; 22: e13235.

57. Kingsland M, Hollis J, Daly J, Elliott E. Smoking, alcohol and weight gain: primary care in the preconception, pregnancy and postnatal periods. Med Today 2022; 23(12): 47-53.