What to do when SSRI and SNRI antidepressants don’t work – a guide for GPs

Failure to respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) or serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) antidepressants is not uncommon in the general practice setting. Several other treatment options may be considered by GPs for such patients.

- Depression is the most common mental health-related presentation in general practice, but only a third of patients achieve remission with first-line selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and many experience significant adverse effects.

- When SSRIs and serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) fail or cause intolerable side effects, GPs can switch to other antidepressants within the same class or between different classes (e.g. mirtazapine, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors) or consider non-PBS-listed options (e.g. agomelatine, vortioxetine, off-label bupropion). GPs can also increase doses, combine medications or augment treatment with antipsychotics.

- Although all antidepressants are more effective than placebo, their efficacy and tolerability differ, with a major meta-analysis finding that agomelatine, mirtazapine and vortioxetine are more effective, and fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and reboxetine are less efficacious with higher dropout rates.

- Bupropion, although not marketed as an antidepressant in Australia, is approved for smoking cessation and has strong evidence supporting its antidepressant efficacy, offering a nonsedating alternative with a distinct side effect profile.

- Consider referring patients for specialist review if treatment failure persists despite trialling other options.

Depression is a common presentation in general practice. According to the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health survey of treatment in general practice, 12% of all GP encounters in 2015–16 were mental health-related, with depression being the most frequent mental health-related encounter, accounting for about one-third of cases.1

In Australia and globally, the most commonly used medications for depression are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). A major challenge for GPs treating patients with depression is that only one-third achieve remission with the first-line SSRI antidepressant and many experience significant adverse effects.2 This leads to a frequent clinical dilemma for GPs: what should be done when patients with depression either fail to respond to, or do not tolerate, SSRIs and SNRIs? This article details general principles for GPs in how to manage this situation and focuses on one of the common strategies (i.e. switching to a different class of antidepressants). Antidepressant options discussed in this article include:

- non-SSRI and non-SNRI PBS-listed antidepressants, such as mirtazapine or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)

- antidepressants approved for marketing by the TGA, but not PBS listed, such as agomelatine and vortioxetine

- antidepressants used ‘off-label’, focusing on bupropion.

Australian GP prescribing practice

Most antidepressant prescribing in Australia is initiated by GPs, with GP prescribing accounting for almost 75% of newly initiated antidepressants.3 A pertinent Australian study investigated the prevalence of SSRI and SNRI treatment failure in patients with depression in Australian clinical practice and the options used by GPs in particular.4 This retrospective cohort analysis was conducted using the Commonwealth PBS 10% sample, which was a systematic random 10% sample of dispensing of prescription medicines subsidised by the Australian government, considered to be representative of prescribing for the Australian population.

Data were extracted for patients aged 16 years or older who had a PBS-listed antidepressant dispensed between July 2013 and June 2019, during which time almost 240,000 patients in the PBS 10% sample commenced treatment with an antidepressant. The researchers examined the first choice of antidepressants, followed by the second and third choices after patients did not respond to, or were unable to tolerate, the first choices (these data were unable to help distinguish between these two common scenarios).

The breakdown of the first-, second- and third-line antidepressants prescribed by GPs is presented in the Table. The study revealed that first-line prescribing broadly follows clinical practice guidelines, although there may be variations depending on the need for tailored treatment in some individuals.4 It should be noted that TCAs are more commonly used in general practice for sleep, pain and anxiety rather than for depression. It should also be emphasised that agomelatine and vortioxetine are not PBS listed, so they are not included in these figures. Aside from these points, these findings suggest a number of treatment choices made by GPs when the first-line antidepressants are ineffective or not tolerated:

- switching within antidepressant classes (particularly within SSRIs)

- transitioning from SSRIs to SNRIs

- increasing the use of noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NASSAs; with mirtazapine being the most prescribed NASSA)

- increasing the dose of antidepressants, with this being found to be used (by all medical practitioners) for 23% of patients4

- combining antidepressants, which was found to be used for 1% of patients and most commonly involved adding a NASSA to an SSRI or SNRI4

- augmenting an antidepressant with an antipsychotic, which was found to be used in 4% of patients.4

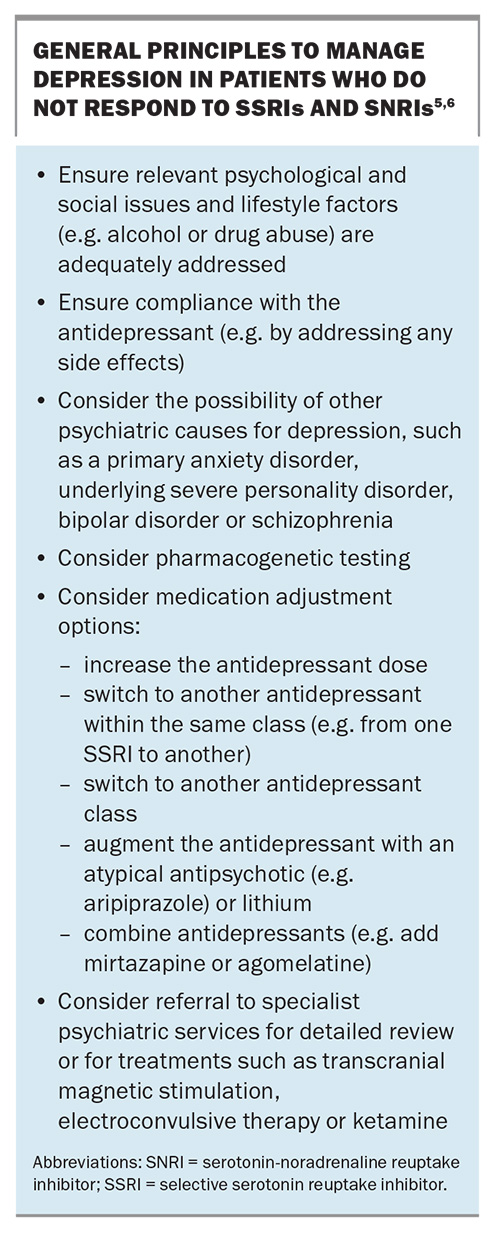

General management principles when antidepressants do not work

The general principles of managing depression in a patient who does not respond to SSRIs and SNRIs have been discussed in detail previously, in articles published in the November 2018 and December 2023 issues of Medicine Today.5 These are outlined in the Box.5,6

The discussion in this article focuses on the strategy of switching the class of antidepressant. Although there is some evidence supporting the efficacy of switching from one SSRI to another, the usual recommended approach is to switch to a different class.2 Switching to a different class should be considered if the depression has not started to improve significantly after two to four weeks of an adequate dose. It should also be considered if the patient cannot tolerate the antidepressant.

Alternative choices of antidepressants that GPs can prescribe include:

- non-SSRI and non-SNRI PBS-listed antidepressants, such as mirtazapine, mianserin, reboxetine, TCAs and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- antidepressants approved for marketing by the TGA, but not PBS listed, such as agomelatine and vortioxetine

- antidepressants used ‘off-label’, i.e. agents not marketed as antidepressants in Australia but approved and marketed in other jurisdictions (e.g. bupropion).

Before focusing on particular antidepressant classes, it should be emphasised that a network meta-analysis has shown that all antidepressants marketed in Australia are more effective than placebo in managing depression.7 Their relative efficacies and tolerabilities were, however, found to differ. Agomelatine, amitriptyline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, paroxetine, venlafaxine and vortioxetine were found to be more effective than other antidepressants, whereas fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and reboxetine were found to be the least efficacious.7 Regarding tolerability, agomelatine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline and vortioxetine were more tolerable than other antidepressants, whereas amitriptyline, clomipramine, duloxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine and venlafaxine were associated with the highest dropout rates.7

Non-SSRI and non-SNRI PBS-listed antidepressants

Mirtazapine

The most common PBS-listed non-SSRI and non-SNRI antidepressant used in general practice in Australia is the NASSA mirtazapine.3 Mirtazapine was approved for marketing in Australia in 1996. It is pharmacologically distinct from other antidepressants, acting on several noradrenergic and serotonergic receptors. Specifically, it is an antagonist of presynaptic alpha2 adrenergic auto- and heteroreceptors, and postsynaptic 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors, leading to increased release of noradrenaline and serotonin into the synapse.

As mirtazapine has anxiolytic properties in addition to being an antidepressant, it is often used to manage depression in patients with comorbid anxiety. In terms of adverse effects, appetite stimulation and weight gain are often substantial, and it may affect sleep, more commonly causing somnolence, but sometimes insomnia. The drug may also cause constipation. Mirtazapine has a similar efficacy to SSRIs, with no significant interactions, although its sedative effect may potentiate the effects of alcohol and benzodiazepines.

Mirtazapine has a bioavailability of 50% and peak plasma concentrations are reached two hours after a dose. The drug is extensively metabolised and has an average half-life of 20 to 40 hours. It is suitable for once-daily dosing with a steady state being reached in three or four days. Clearance may be reduced by hepatic or renal impairment. Treatment begins with 15 mg daily, and the drug is available in 15 mg, 30 mg and 45 mg doses. The dose generally needs to be increased to obtain an optimal clinical response, with an average optimal therapeutic dose of 30 mg.8

Less commonly used antidepressants

Mianserin, another NASSA (with a tetracyclic molecular structure), is an older antidepressant that was approved in 1978. As mianserin is not commonly used in either general practice or psychiatric settings, it will not be discussed further. The noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor reboxetine will similarly not be considered further, as it is rarely used because of its poor tolerability and modest efficacy.

TCAs are less commonly used in general practice as antidepressants, mainly being used in small doses for anxiety, insomnia and pain. Their use as antidepressants is now mostly in specialist psychiatric practice. Similarly, the older (‘irreversible’) MAOIs are rarely initiated in general practice, largely because of the need for significant dietary restrictions (avoiding foods containing tyramine) and risk of significant drug interactions (e.g. with pethidine). Nonetheless, specialists familiar with less treatment-responsive presentations of depression are aware that both TCAs and MAOIs are, in general, more effective than SSRIs and SNRIs. In current practice, TCAs and MAOIs are now regarded as best initiated by psychiatrists, although for GPs familiar with TCAs, they can be a useful option in patients with a poor response to SSRIs and SNRIs.

Some practitioners may consider the use of these antidepressants as ‘dangerous and old fashioned’, which can lead to considerable patient distress if they are ceased by GPs without consultation with the psychiatrist.

Although the relatively newer (‘reversible’) MAOI moclobemide was marketed with considerable optimism in the 1990s, it has been shown to be a weak antidepressant and is now rarely used.

TGA-approved antidepressants that are not PBS listed

Agomelatine

Agomelatine was approved for marketing in Australia in 2010. It is indicated for both acute and preventive treatment of major depressive disorder and treatment of generalised anxiety disorder. Agomelatine is both an agonist of the melatonin receptor and a blocker of one of the serotonin receptors (5-HT2C), although it is not clear which of these actions is predominantly responsible for the antidepressant effect.

Adverse events associated with agomelatine are usually mild or moderate and occur in the first few weeks of treatment. The most common adverse events are headache, nausea and dizziness. These adverse events are usually transient. In practice, side effects are minimal with this antidepressant. It may be less likely to cause sexual side effects compared with SSRIs.

Routine monitoring of liver function is recommended both prior and subsequent to initiation of agomelatine in view of its relatively common elevation in liver enzyme levels (affecting 1 to 2% of prescribed patients). During treatment, transaminase levels should be monitored periodically after about three, six, 12 and 24 weeks, with this regimen to be repeated following a dose increase to 50 mg. Treatment should be discontinued if serum transaminase levels are greater than three-fold the upper limit of the normal range.

Agomelatine is mainly metabolised in the liver by cytochromes CYP1A2 (90%) and CYP2C9/19 (10%). It is therefore contraindicated in patients with impaired liver function or patients taking potential inhibitors of CYP450 and CYP1A2, such as fluvoxamine, efavirenz, ticlopidine and gemfibrozil. Similarly, inducers of these enzymes (e.g. rifampicin) may reduce the bioavailability and, therefore, the clinical efficacy of agomelatine. In terms of dosage, patients are started on 25 mg at night, with some needing a further dose increase to 50 mg. It is usually prescribed as a nighttime dose because it is mildly sedative.

Vortioxetine

Vortioxetine was approved for marketing in Australia in 2014. It acts by inhibiting serotonin uptake, similar to the action of SSRIs, and also acts on several serotonin receptors, specifically blocking the serotonin 3, 7 and 1D receptors and stimulating serotonin 1A and 1B receptors.

The most common side effects of vortioxetine (occurring in at least 5% of patients) are nausea, headache, diarrhoea, dizziness, dry mouth, constipation and vomiting. Less common side effects include abdominal discomfort, fatigue, somnolence, weight increase, back pain, tremor and sedation. Sexual dysfunction occurs in 23 to 34% of females and 20 to 29% of males.

There has been some interest in a possible cognition-enhancing action of vortioxetine. A study in rats found evidence of a pro-cognitive effect that was not seen with escitalopram or duloxetine.9 A meta-analysis of antidepressant studies in patients with major depressive disorder found that vortioxetine appeared to have the largest effect size on psychomotor speed, executive control and cognitive control, whereas duloxetine had the greatest effect on delayed recall.10 A further meta-analysis found that the antidepressant efficacy of vortioxetine was not moderated by baseline cognition.11 A recent review of the effects of antidepressants on cognition in older patients with depression found preliminary evidence that sertraline and vortioxetine had significant positive effects on processing speed and memory.12

The usual ongoing dose of vortioxetine ranges from 5 mg to a maximum dose of 20 mg.

Antidepressants used ‘off-label’

Antidepressants used ‘off-label’ are not marketed as antidepressants in Australia but are approved and marketed in other jurisdictions. Bupropion was approved for marketing as an antidepressant in the USA in 1985. As it has been off-patent for many years, it has not been marketed as an antidepressant in Australia because of a lack of commercial incentive. It was, however, approved in Australia for the indication of managing smoking cessation in 2001, and is therefore available for ‘off-label’ (nonsubsidised) prescription, in view of the strong evidence from many US studies of its antidepressant efficacy.13

Bupropion differs pharmacologically from other antidepressants available in Australia because of its combined noradrenaline-dopamine uptake inhibition, resulting in increased neurotransmission of these neurotransmitters in the synaptic cleft. In 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration approved a combination of dextromethorphan and bupropion for the treatment of major depressive disorder, with dextromethorphan acting as an antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors and an agonist at sigma-1 receptors. This combination treatment is not yet available in Australia. Bupropion differs clinically from many other antidepressants in being an energising, rather than sedating, antidepressant. Adverse effects include anxiety, insomnia, agitation, headache and nausea. The antidepressant dose range is usually 150 mg once daily or 150 mg twice daily (morning and midday) with a maximum dose of 450 mg, as higher doses have been associated with an increased risk of seizures.14

Conclusion

There is a wide range of effective treatment options for the GP to consider when patients with depression fail to respond to SSRI or SNRI antidepressants. Thirty percent of patients may achieve remission with a first-line SSRI, but it is still worthwhile trialling some of the suggested treatment options, as it has been demonstrated that at least 30% more will respond well to subsequent treatment options.2 MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, et al. General practice activity in Australia 2015-16. General practice series no. 40. Sydney: Sydney University Press; 2016.

2. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1905-1917.

3. McManus P, Mant A, Mitchell P, Britt H, Dudley J. Use of antidepressants by general practitioners and psychiatrists in Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2003; 37: 184-189.

4. Malhi GS, Acar M, Kouhkamari MH, et al. Antidepressant prescribing patterns in Australia. BJPsych Open 2022; 8: e120, 1-7.

5. Mitchell PB. Management of treatment-resistant depression. A guide for GPs. Medicine Today 2018; 19(11): 41-44.

6. Mitchell PB. Using antidepressants in general practice: is there a role for pharmacogenomic testing? Medicine Today 2023; 24(12): 42-45.

7. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018; 391: 1357-1366.

8. Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Cowen PJ, Leucht S, Egger M, Salanti G. Optimal dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine in major depression: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatr 2019; 6: 601-609.

9. Jensen JB, du Jardin KG, Song D, et al. Vortioxetine, but not escitalopram or duloxetine, reverses memory impairment induced by central 5-HT depletion in rats: evidence for direct 5-HT receptor modulation. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2014; 24: 148-159.

10. Rosenblat JD, Kakar R, McIntyre RS. The cognitive effects of antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2015; 19: pyv082.

11. Jordan JT, Shen L, Cooper NJ, et al. Baseline cognition is not associated with depression outcomes in vortioxetine for major depressive disorder: findings from placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2024; 85: 24m15295.

12. Nelson JG, Gandelman JA, Mackin RS. A systematic review of antidepressants and psychotherapy commonly used in the treatment of late life depression for their effects on cognition. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr 2024: S1064 -7481(24)00443-3.

13. Blaszczyk AT, Mathys M, Le J. A review of therapeutics for treatment-resistant depression in the older adult. Drugs Aging 2023; 40: 785-813.

14. Detyniecki K. Do psychotropic drugs cause epileptic seizures? A review of the available evidence. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2022: 55: 267-279.