The impact of depression on diabetes: an inextricable relationship

Depression and diabetes are two of the most common chronic illnesses in general practice. Sensitive and holistic management of these conditions as coinciding comorbidities requires an understanding of their multifaceted, bidirectional relationship. Regular screening and monitoring for both conditions are recommended.

Note

This is an online update of the original version of this article that was published in the January/February 2023 issue of Medicine Today. This update was prepared for National Diabetes Week 2024.

- Depression and diabetes have a bidirectional relationship, precipitated by common environmental and psychosocial factors and shared physiological mechanisms, including dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.

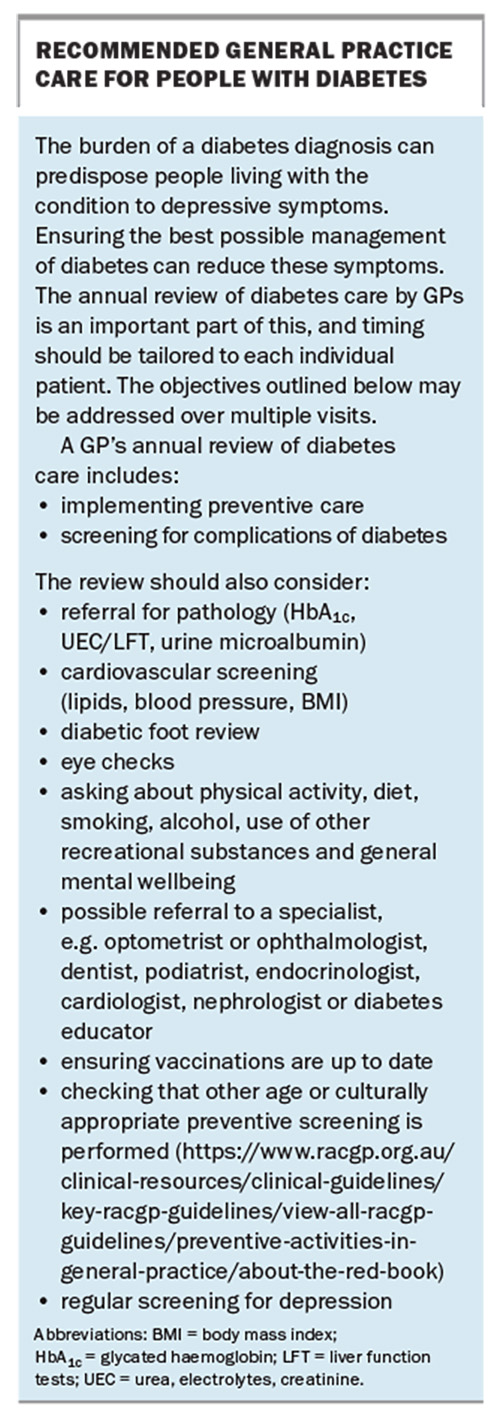

- Screening and regular review over multiple visits are essential for people with either condition, and should include a comprehensive annual review in patients with an existing diagnosis of diabetes.

- Precise questioning in taking a history offers opportunities for targeted treatment strategies.

- Management of coinciding depression and diabetes requires a supportive, sensitive and holistic approach, with the aims of simplifying pharmacotherapy and reducing anxiety and distress where possible. Psychotherapy should be considered.

- Improving health outcomes for people with one condition increases the likelihood of reaching treatment targets in the other.

Depression and diabetes are common conditions that are frequently comorbid, and each impacts on the other. Compared with people without diabetes, depression prevalence rates can be as much as three times higher in people with type 1 diabetes and twice as high in people with type 2 diabetes.1,2 Prevalence rates vary widely because of the range of methods for defining depression. Sadly, diabetes prevalence has been increasing yearly in Australia.3

A paper entitled ‘Depression and diabetes: a potentially lethal combination’ gave a sobering assessment of the relationship: ‘Depression has been linked to having a higher number of Framingham risk factors (i.e. smoking, obesity, sedentary lifestyle) for cardiac disease in patients with diabetes and … poor adherence to self-care regimens, such as glucose monitoring, diet, exercise regimens, taking medications as prescribed. Depression is also associated with physiologic dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system, as well as an increase in inflammatory markers, which may also adversely affect the course of diabetes. Given the adverse effect on self-care and physiological dysregulation, it is not surprising that longitudinal studies have also shown that depression is linked with an increased risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications … Comorbid depression is not only linked to a higher risk for diabetic complications, but also a higher risk for mortality.’4

Depression can be seen as an understandable reaction to the demands of diabetes as a lifelong condition with possible significant, often debilitating complications. Some other potential mechanisms that may underlie the high coprevalence include lifestyle factors, genetics and family history, metabolic processes, temperament and coping styles. There is also evidence suggesting that familial relationships and burden of a lifelong disorder with onset early in personality development may contribute to increased vulnerability to depression.1,2

This article discusses the depression–diabetes relationship and the management of depression in those with diabetes, and then considers how GPs can screen for and assess depression in people with diabetes and problem solve medication issues.

Physiological factors

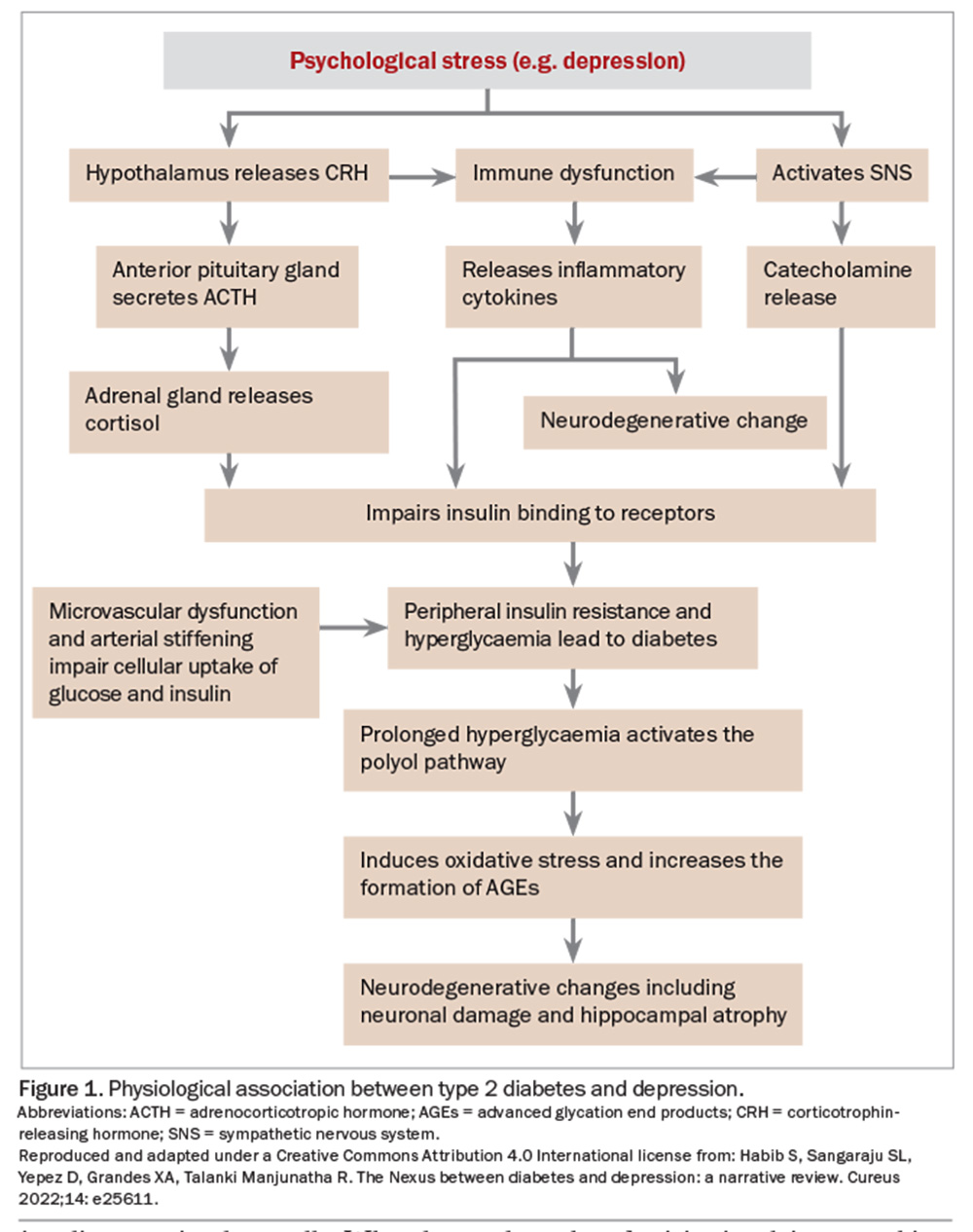

There are bidirectional effects of stress and labile blood sugars. HPA axis disruption in depression can manifest as subclinical hypercortisolism, blunted diurnal cortisol rhythm or hypocortisolism with impaired glucocorticoid sensitivity and increased inflammation.5,6 Diabetes has similar effects on the HPA axis, and is accentuated by chronic stress (Figure 1).

Cognition and mood are affected by hyperglycaemia and, potentially, hypoglycaemia. Brain MRIs of people with type 1 diabetes have shown higher prefrontal glutamate-glutamine-gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels than in healthy controls, which correlate with mild depressive symptoms.6 The anti-inflammatory effect of GABA may be crucial in the pancreatic islets as GABA has a role in increasing the survival of insulin-secreting beta cells. When beta cells decrease in number and disappear from the islets, GABA is also decreased, along with its protective shielding of the beta cells. Increases in inflammatory molecules may weaken and even kill the remaining beta cells.7 Further, animal models have shown that diabetes negatively affects hippocampal integrity and neurogenesis, which may interact with other aspects of neuroplasticity and contribute to mood symptoms in diabetes.8

Linked pathogenesis

There is growing interest in the proposition that depression and type 2 diabetes have shared origins involving a cytokine-mediated inflammatory response dysregulation of the HPA axis.1,2 Throughout life, these pathways can lead to insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease, depression, increased risk of type 2 diabetes and increased mortality – although mechanisms are not as clear for type 1 diabetes.

Later onset cerebral microvascular disease can lead to ‘vascular depression’, often with melancholic symptoms. Longer term noncardiovascular complications of diabetes also arise at this stage of life, including cancer, liver disease and cognitive dysfunction; these are also often comorbid with depression.1

Environmental and social factors

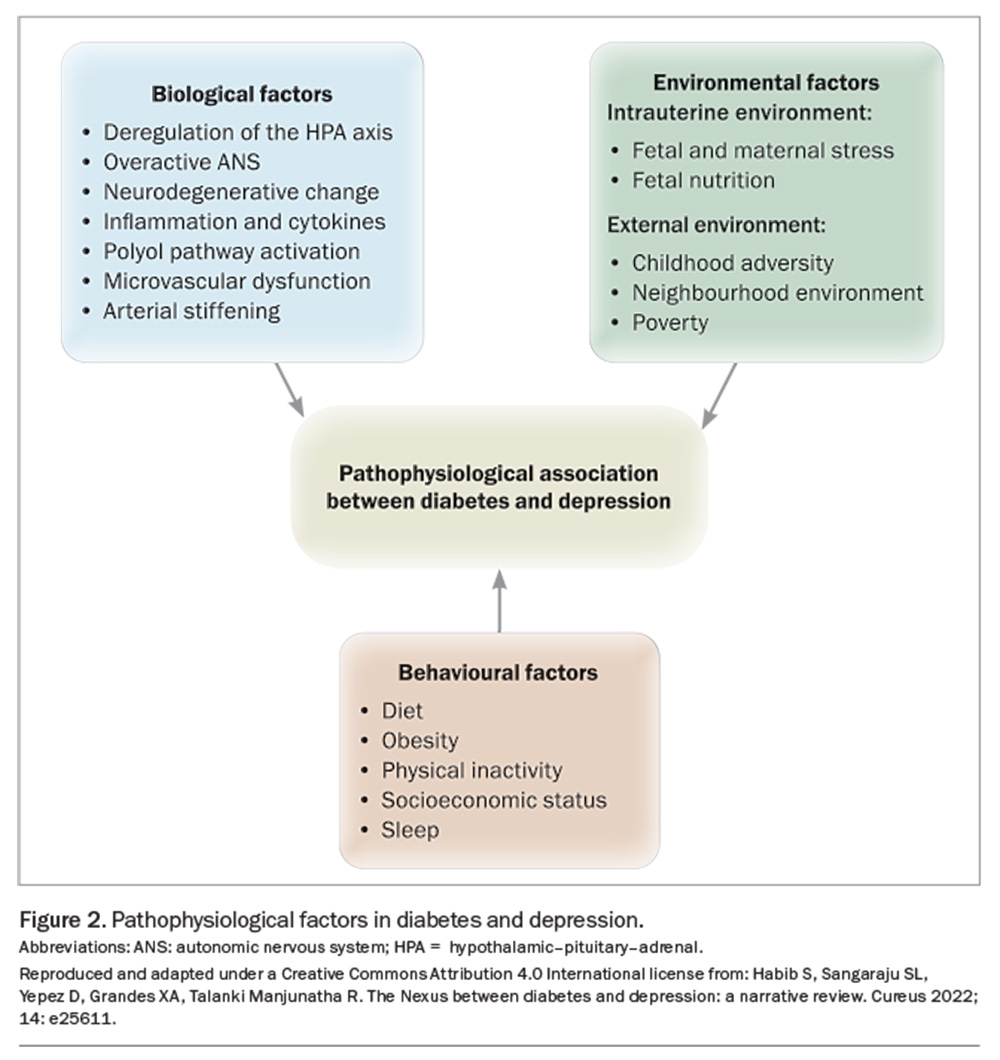

Factors such as socioeconomic status and local environment influence predisposition to depression and diabetes (Figure 2). Poor physical environments (e.g. traffic, noise, decreased walkability, lack of green space) and social environments (e.g. lower social cohesion and social capital, increased violence, decreased residential stability) are associated with poorer diet and physical activity patterns, obesity, diabetes, hypertension and depression.1,9,10 Adverse neighbourhood environments have also been associated with HPA axis dysfunction, a blunted circadian rhythm and enhanced inflammation.1 Of note, smoking and depression are bidirectionally associated and both increase insulin resistance.

Treatment-related factors and complications

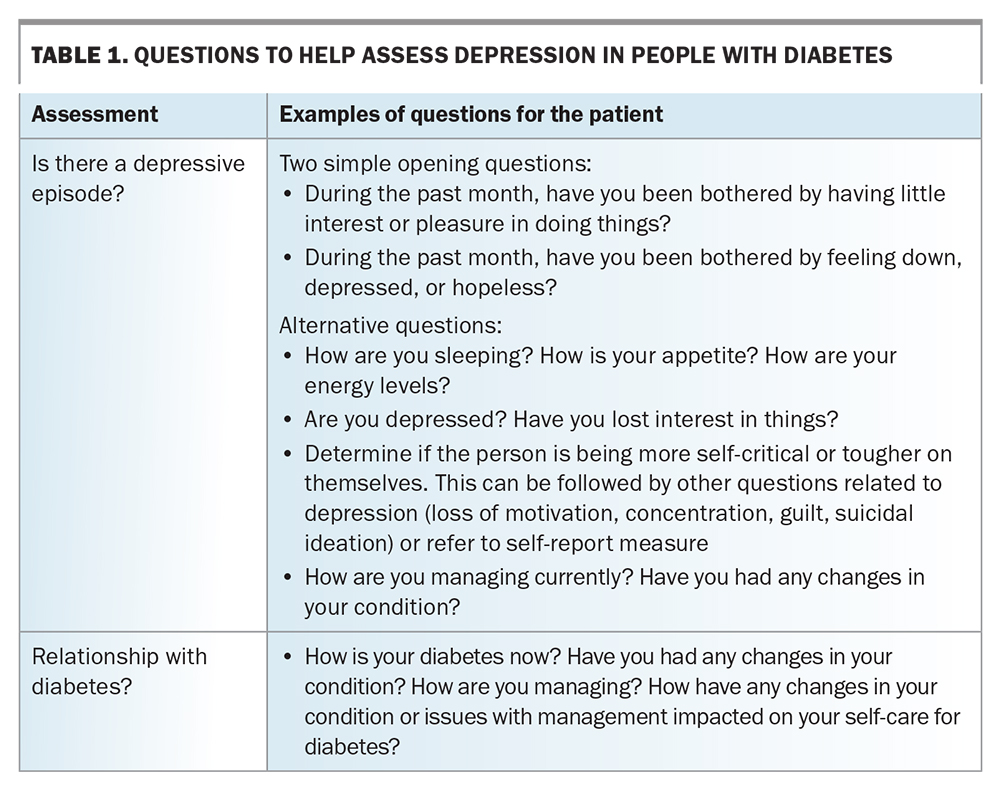

Apart from psychological factors, the psychosocial burden of a diabetes diagnosis and its potential complications predispose people living with diabetes to depressive symptoms. Table 1 provides some questions that clinicians can ask to assess for depression in people living with diabetes. Patients with depression can neglect their self-care and, importantly, their diabetes management. A meta-analysis of 47 independent study samples, including 17,319 participants, found that depression was significantly associated with missed medical appointments and neglecting recommendations about diet, exercise, medication use, blood glucose monitoring and foot care.11 The GP’s role in providing recommended diabetes care is discussed in the Box.

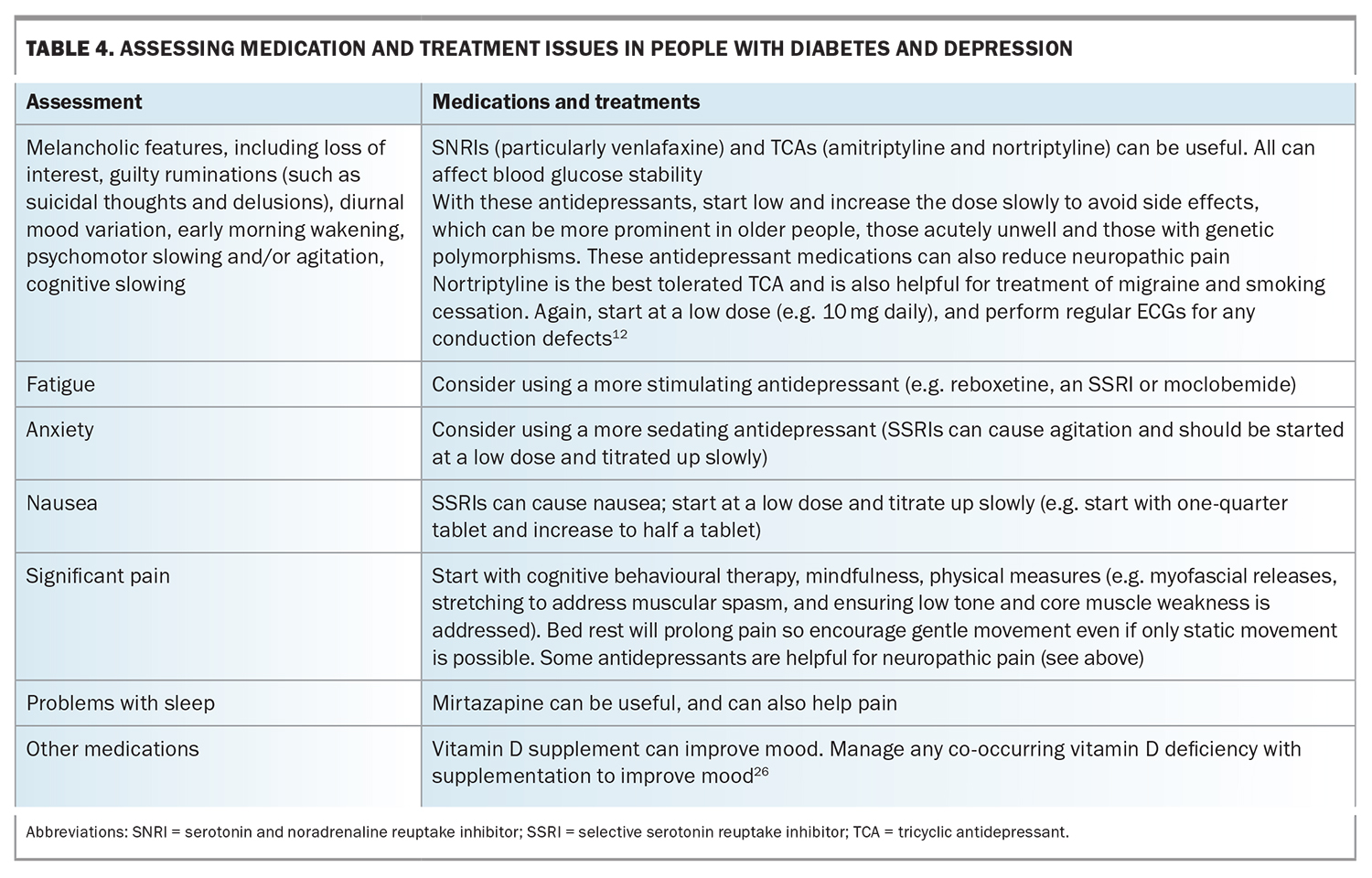

Antidepressant medications can contribute to the risk of diabetes. Randomised controlled trials have shown that these medications vary in their effects on appetite, weight and blood glucose levels (both hyperglycaemic and hypoglycaemic effects have been observed).12 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) effectively treat depression in people living with diabetes and positively influence glycaemic control. (See also the section ‘Antidepressants and diabetes’ later in this article.)

A one-point increase in scores for depressive symptoms was found to result in a 10% increased risk of nonadherence to fruit and vegetable intake and foot care in people with diabetes.1 This suggests a mutually reinforcing phenomenon, where poorer adherence to self-care may increase blood glucose levels, contributing to depressive symptoms and a decline in self-care behaviours.

Diabetes can present with or exacerbate fatigue and ‘brain fog’, which can impact motivation and activity levels. People living with diabetes and clinicians can misinterpret these symptoms as psychological in cause, particularly in those with prior history of depression.1,5,13

Mitigation and management

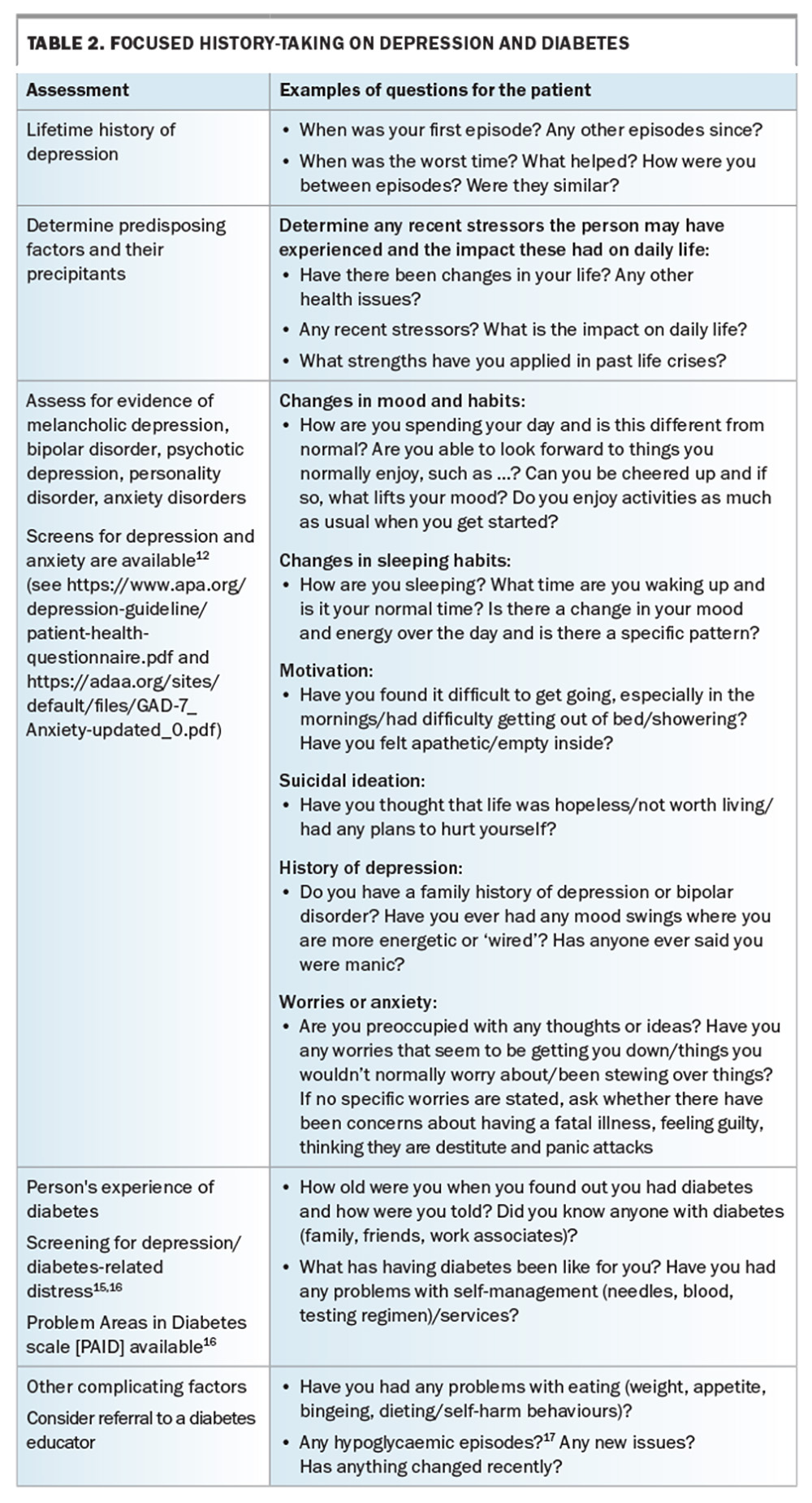

It has been suggested that people with chronic conditions such as diabetes can feel blame and shame if complications arise. Thus, complications can be reframed more positively by using words focusing on care, so that people are more engaged with their own management and feel more supported.11 This promotes their working with their healthcare professionals to minimise the risk of complications and to treat early and effectively those that do occur. Resources to aid in this approach are discussed later in this article. Table 2 provides suggestions for focused history-taking in patients with depression and diabetes.14-17 When diabetes and depression coexist, treating the underlying diabetes can significantly improve psychosocial functioning and mood. Metformin may assist with weight loss, which may lessen associated shame and guilt. Improving diabetes control can improve peripheral neuropathy, which may have impaired mobility.18 Patients may need support with core strengthening and gradually increasing their exercise tolerance if there has been significant muscle wasting from prolonged immobility.19

Regular blood glucose self-monitoring is important to recognise symptoms and triggers of hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia and their correct interpretation.1,13 Misconceptions can otherwise make it challenging to maintain blood glucose levels to target, and can be associated with inappropriate compensatory mechanisms.

Anxiety can potentiate medication side effects and nocebo effects, where the person may experience a detrimental effect from treatment triggered by the anticipation that this will occur. Certain medications and insulin require more regular monitoring, which can exacerbate distress. Many people with diabetes report avoiding testing and treatment as it reminds them of the disease process.

Simplifying testing and treatment processes can be helpful. One strategy is to spread blood glucose self-monitoring throughout the week, rather than intensively throughout the day, to ensure the capacity to capture some recordings at a frequency that is tolerable for the individual. Fixed-dose medication combinations may be suitable for some people with diabetes, and can be available as weekly injections, although some individuals may still prefer daily dosing. Having visual or alarm reminders can also help with medication adherence. Healthcare professionals and the patient working together with regular review can reduce anxiety and the nocebo effect, particularly on commencing treatment or if the person is experiencing cognitive slowing due to depression.

Issues related to personality and coping styles

A review of 11 studies found no difference in depression rates among those with undiagnosed diabetes, those with impaired glucose metabolism and people with normal glucose metabolism, suggesting that the actual knowledge of having diabetes and the implications added to the burden and depression onset.20 The review highlights the importance of how clinicians provide information about diabetes, and what support is given at and after diagnosis. However, no distinction was made for diabetes distress, which can overlap with depression.

Diabetes distress refers to the frequently hidden emotional burdens, stresses and worries that are part of managing a demanding, progressive, chronic condition like diabetes.21 Diabetes distress can have early onset in people with diabetes who have experience of diabetes in friends or family.1,21 Grieving the loss of ‘wellness’ and what a diagnosis may entail can engender distress even in those who do not fully fit the criteria of major depressive disorder.21

There are interesting correlations between adult attachment style and diabetes outcomes, specifically glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels and self-management. Ciechanowski et al. found that people with diabetes fit into one of four attachment style groups: secure attachment (about 44%), dismissing attachment (about 36%), fearful attachment (about 12%) and preoccupied attachment ( about 8%).22,23 Those in the secure group had the lowest mean HbA1clevel, whereas those in the fearful and preoccupied groups had intermediate HbA1c levels. Those with a dismissing attachment style had significantly higher HbA1c levels than the other groups and the poorest self-management of their diabetes.

Management of depression and the effect on glycaemic control

Individuals may prefer or be more suitable for either psychotherapy (individual, group or online) or pharmacotherapy or a combination of both. As already discussed in this article, improvement of glycaemic control may bidirectionally improve mood.

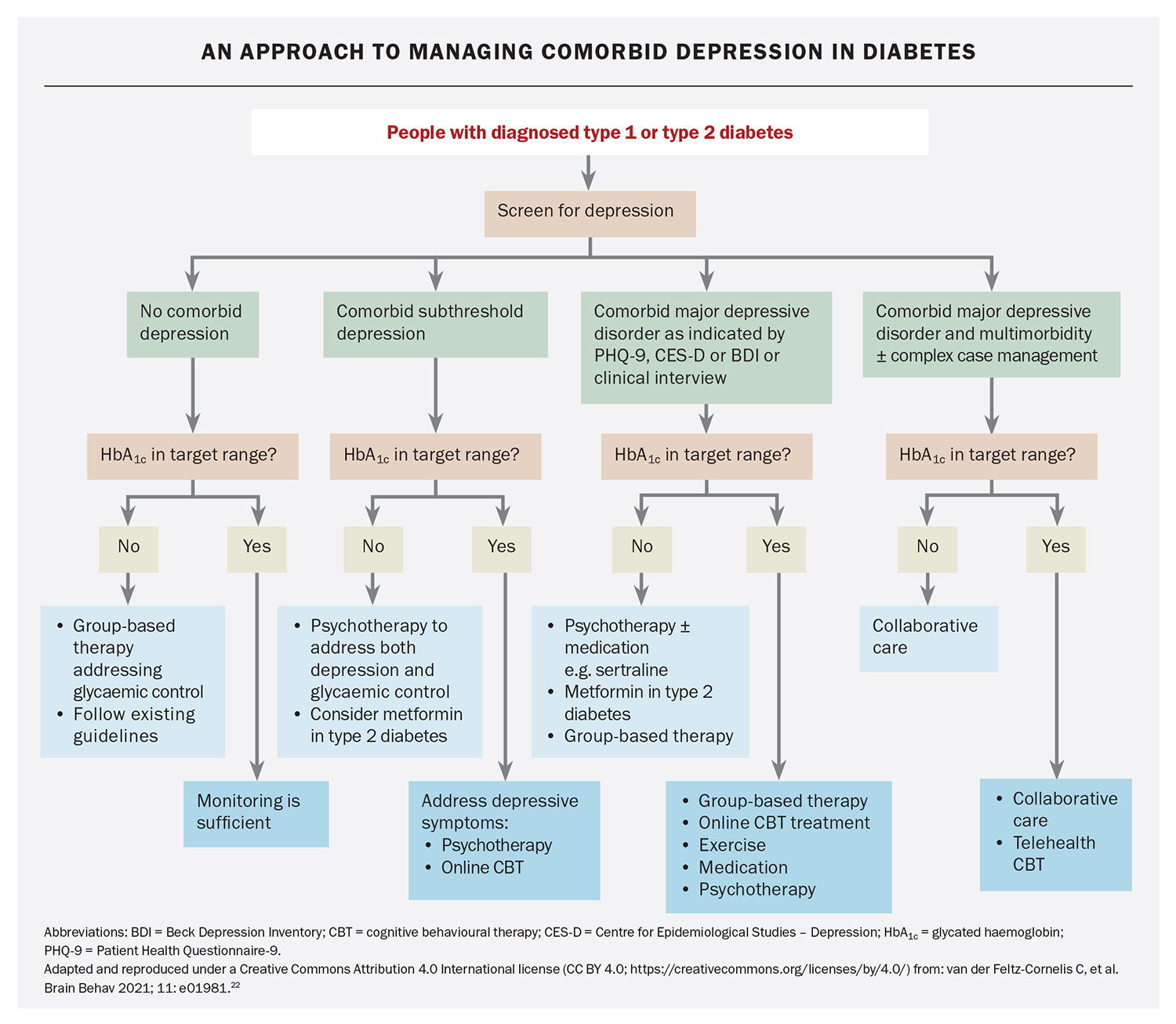

A systematic review by van der Feltz suggests that in people with diabetes and subthreshold depression, more individualised psychotherapy may achieve better outcomes – although the mechanisms for this requires more research.12 Assessment based on the individual’s circumstances and needs will still be required. An approach to treating subthreshold depression and comorbid depressive disorder in diabetes is presented in the Flowchart.12

Antidepressants and diabetes

Antidepressant medications (SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs] and serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs]) are associated with increased risk of diabetes onset, especially with TCAs and concurrent use of SSRIs and TCAs. Antidepressant medications within the same class may differ in terms of their impact on glucose metabolism and should be examined individually. A study that estimated the impact of citalopram, amitriptyline, venlafaxine and escitalopram on glycaemic control in Canadian primary care patients with diabetes found escitalopram to have the least effect.14

Implications for clinical practice

Screening for and addressing depression in people with diabetes is now recognised in the guidelines of several countries and by the International Diabetes Federation, but if GPs are to screen, they need to have interventions that they can provide. Screening can be completed in waiting rooms, as ‘homework’ or with the assistance of a practice nurse.

For people with diabetes who are depressed, it is helpful to focus on practical strategies, including the specific ‘lifestyle factors’ of dietary modification and exercise. One of the challenges in diabetes care is the amount of misinformation on diet, so it is best to check the person’s information sources.

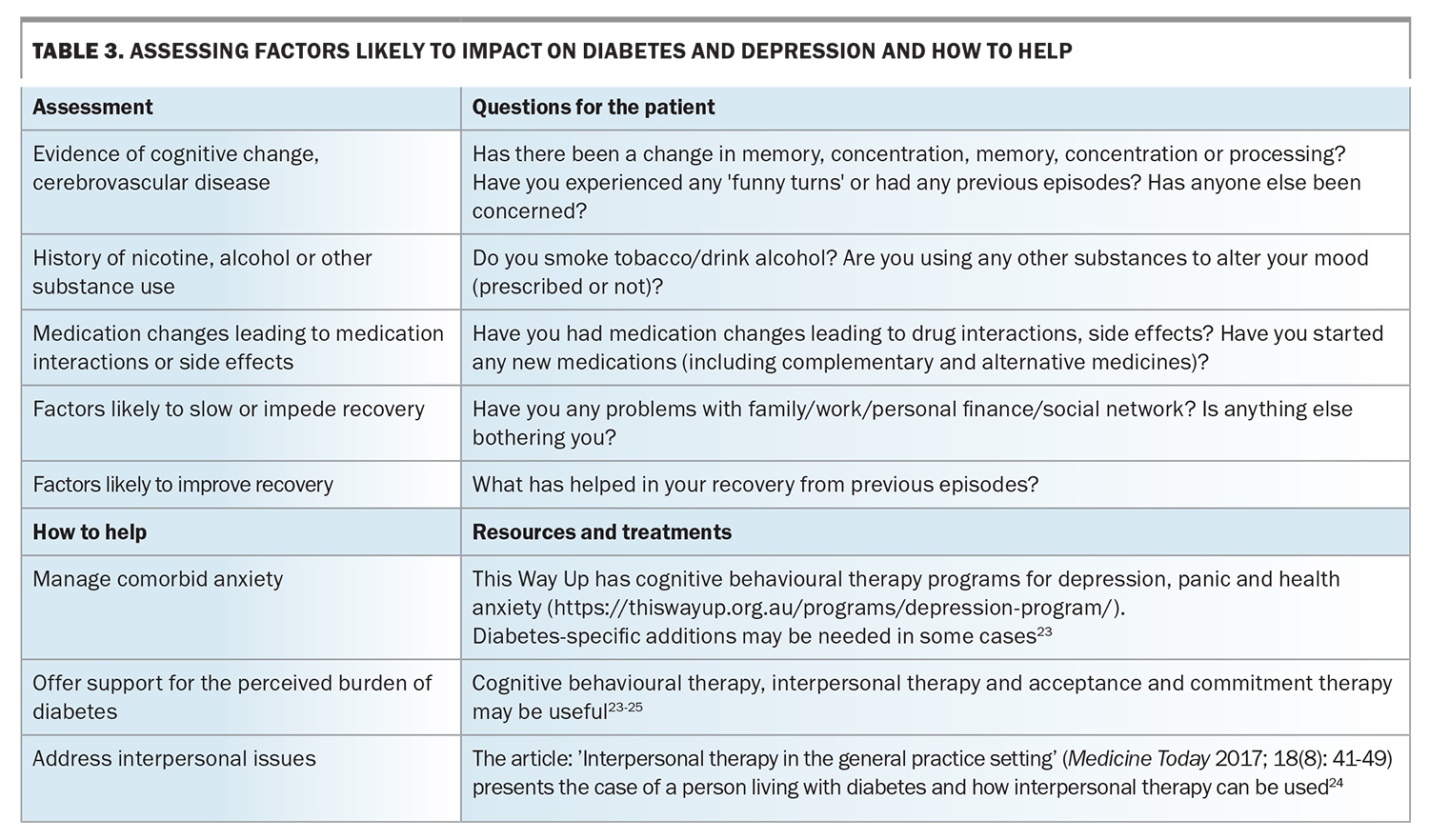

Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 provide a framework for assessing depression and its management in people living with diabetes.14-17,24-26 Persons with comorbid depression and diabetes may require greater support and scaffolding, including naming what they are having difficulty with, particularly in the presence of cognitive slowing and complexity. The simplest way of screening – ‘just asking’ – is probably the first step (Table 1), followed by more focused history-taking (Tables 2 to 4), although it is not expected that all the questions would be required or attempted at one sitting.

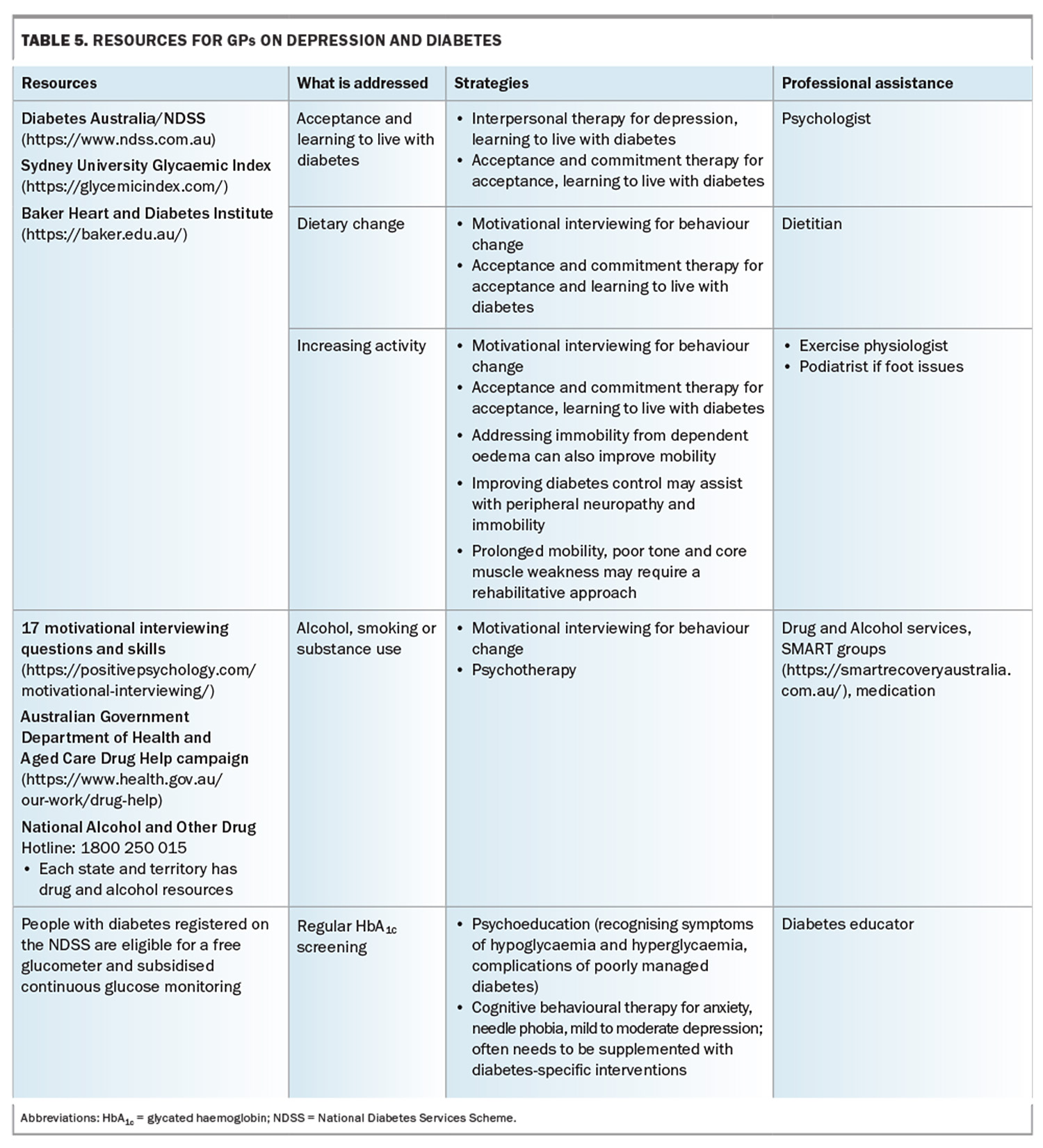

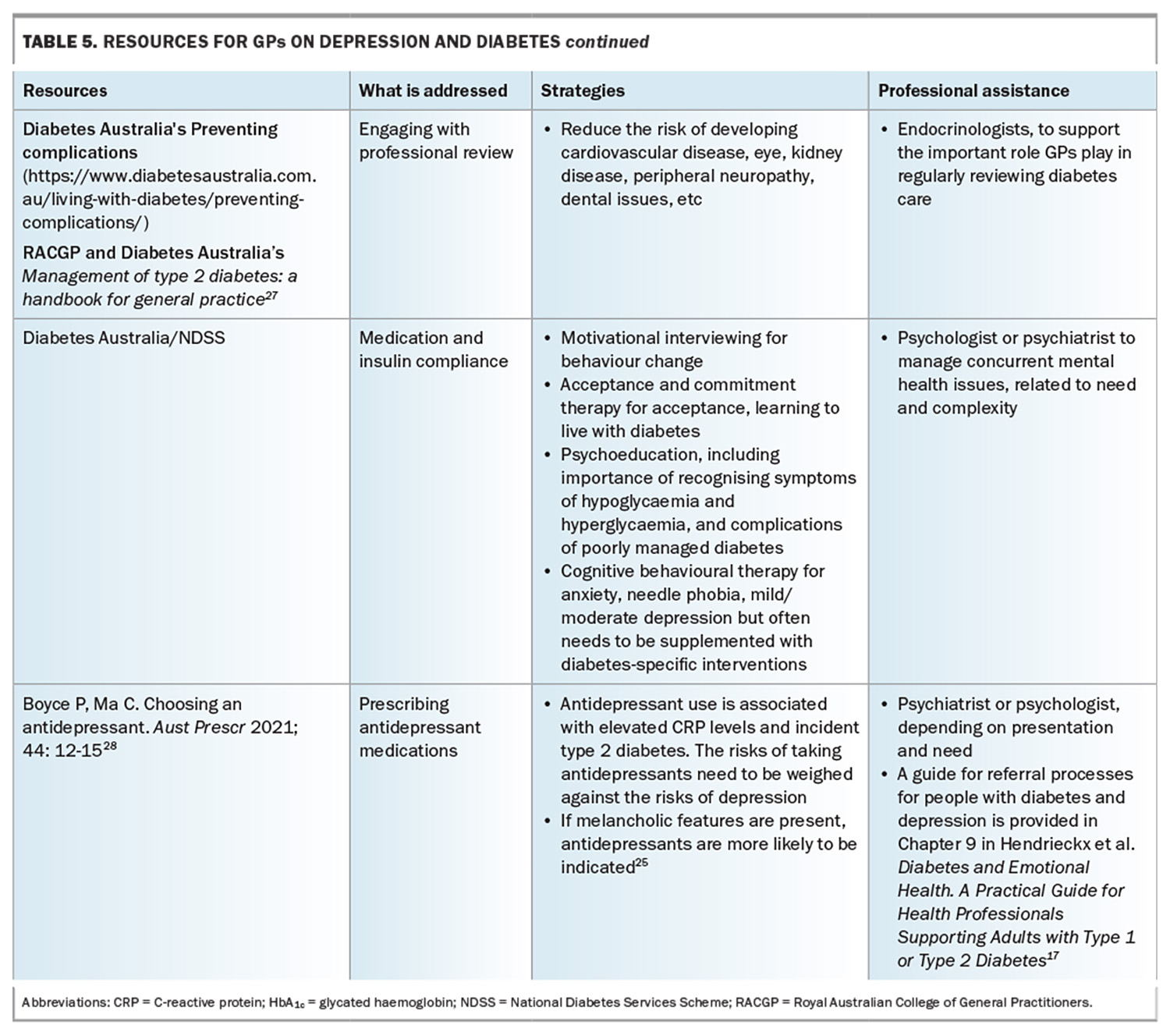

Table 5 (Table 5 cont.) outlines useful resources to address a range of complications in people with diabetes and depression, as well as relevant professional who can assist.17,25,27,28 The National Diabetes Services Scheme’s Diabetes and Emotional Health: A Practical Guide for Health Professionals Supporting Adults with Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes, 2nd edition’ is a useful resource.17

Conclusion

The impact of depression on diabetes is multifaceted and depends on the person's age and timing related to the diabetes journey, previous coping styles and how they are currently managing their diabetes, as well as their life situation and general health. It is important to acknowledge the prevalence of depression and diabetes co-occurring and ask about it. People presenting with both depression and diabetes are more likely to have complications from both conditions, have more challenges with managing these and require more support and understanding to overcome these difficulties. Narrowing down by asking about specific issues can enable targeted strategies. Improving depression can improve diabetes control.

Improving depression can improve diabetes control, and improving diabetes control can improve mental wellbeing; GPs can play an important role with managing this complexity. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Holt RI, de Groot M, Golden SH. Diabetes and depression. Curr Diab Rep 2014; 14: 491.

2. Moulton CD, Pickup JC, Ismail K. The link between depression and diabetes: the search for shared mechanisms. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3: 461-471.

3. Diabetes Australia. 2023 snapshot: Diabetes in Australia. © Diabetes Australia. Available online at: https://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023-Snapshot-Diabetes-in-Australia.pdf (accessed July 2024).

4. Katon W, Fan MY, Unützer J, Taylor J, Pincus H, Schoenbaum M. Depression and diabetes: a potentially lethal combination. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23: 1571-1575.

5. Tomic D, Shaw JE, Magliano DJ. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022; 18: 525-539.

6. Doolin K, Farrell C, Tozzi L, Harkin A, Frodl T, O’Keane V. Diurnal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis measures and inflammatory marker correlates in major depressive disorder. Int J Mol Sci 2017; 18: 2226.

7. Bhandage AK, Jin Z, Korol SV, et al. GABA regulates release of inflammatory cytokines from peripheral blood mononuclear cells and CD4+ T cells and is immunosuppressive in type 1 diabetes. EBioMedicine 2018; 30: 283-294.

8. de Cossío LF, Fourrier C, Sauvant J, et al. Impact of prebiotics on metabolic and behavioral alterations in a mouse model of metabolic syndrome. Brain Behav Immun 2017; 64: 33-49.

9. de Vet E, de Ridder DT, de Wit JB. Environmental correlates of physical activity and dietary behaviours among young people: a systematic review of reviews. Obes Rev 2011; 12: 130-142.

10. Amuda AT, Berkowitz SA. Diabetes and the built environment: evidence and policies. Curr Diab Rep 2019; 19: 35.

11. Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 2398-2403.

12. van der Feltz-Cornelis C, Allen SF, Holt RIG, Roberts R, Nouwen A, Sartorius N. Treatment for comorbid depressive disorder or subthreshold depression in diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav 2021; 11: e01981.

13. Petrak F, Baumeister H, Skinner TC, Brown A, Holt RIG. Depression and diabetes: treatment and health-care delivery. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015; 3: 472-485.

14. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Depressive symptoms, antidepressant medication use, and inflammatory markers in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Psychosom Med 2018; 80: 167-173.

15. Wilhelm K, Reddy J, Crawford J, Robins L, Campbell L, Proudfoot J. The importance of screening for mild depression in adults with diabetes. Transl Biomed 2017; 8:1 doi:10.2167/2172-0479.1000101.

16. Reddy J, Wilhelm K, Campbell L. Putting PAID to diabetes-related distress: the potential utility of the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) scale in patients with diabetes. Psychosomatics 2013; 54: 44-51.

17. Hendrieckx C, Halliday JA, Beeney LJ, Speight J. Diabetes and emotional health: a practical guide for health professionals supporting adults with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. 2nd ed. Canberra: National Diabetes Services Scheme; 2020. Available online at: https://www.ndss.com.au/wp-content/uploads/resources/diabetes-emotional-health-handbook.pdf (accessed July 2024).

18. Aroda VR, Knowler WC, Crandall JP, et al. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Metformin for diabetes prevention: insights gained from the Diabetes Prevention Program/Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Diabetologia 2017; 60: 1601-1611.

19. Calcutt NA. Diabetic neuropathy and neuropathic pain: a (con)fusion of pathogenic mechanisms? Pain 2020; 161 Suppl 1: S65-S86.

20. Nouwen A, Winkley K, Twisk J, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for the onset of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2010; 53: 2480-2486.

21. Fisher L, Gonzalez JS, Polonsky WH. The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision. Diabet Med 2014; 31: 764-772.

22. Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, et al. Influence of patient attachment style on self-care and outcomes in diabetes. Psychosom Med 2004; 66: 720-728.

23. Wilhelm K, Tietze T. Difficult doctor–patient interactions: applying principles of attachment-based care. Med Today 2016; 17(1-2): 36-44.

24. Newby J, Robins L, Wilhelm K, et al. Web-based cognitive behaviour therapy for depression in people with diabetes mellitus: a randomised controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e157.

25. Wilhelm K, May R. Interpersonal therapy in the general practice setting. Med Today 2017; 18(8): 41-49.

26. Amsberg S, Wijk I, Livheim F, Toft E, Johansson U-B, Anderbro T. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for adult type 1 diabetes management: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018; 8: e022234.

27. Royal College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Management of type 2 diabetes: a handbook for general practice. Melbourne: RACGP and Diabetes Australia; 2020.

28. Boyce P, Ma C. Choosing an antidepressant. Aust Prescr 2021; 44: 12-15.