The menopause transition: managing symptoms and improving quality of life

The menopause transition may be associated with significant symptoms that require additional care and support. Co-ordinated management between specialists and GPs can facilitate the holistic care of patients during this period.

- The menopause transition is defined as the period leading up to the final menses. Women can present with a range of symptoms, such as irregular bleeding, vasomotor symptoms, genitourinary concerns and psychological changes.

- Referral to a gynaecologist may be necessary if initial treatments are ineffective or if further investigations are warranted.

- Shared care between specialists and GPs ensures comprehensive management while prioritising overall health and lifestyle interventions.

- General health considerations include cardiovascular and bone health, with caution in terms of long-term hormone therapy use.

The menopause transition (MT), also called perimenopause, is the period leading up to the final menses. A woman is considered postmenopausal 12 months after her final menstrual period. The constellation of changes that can develop during the MT can sometimes cause distress. The reduced ovarian follicular pool leads to intermittent ovulation, irregularity in cycles and reduced ovarian oestradiol and progesterone production. This article discusses the primary symptoms that can arise during the MT, how management during this period may differ from the management of menopausal symptoms, when referral to a gynaecologist may be indicated and some practical considerations for providing holistic care during the MT. We recognise and respect that nonbinary and transgender individuals can experience symptoms of the MT, and our intention is to be inclusive in our language and representation. For the purposes of this article, we refer to cisgender women (hereafter referred to as women).

How and why does the patient present to a GP?

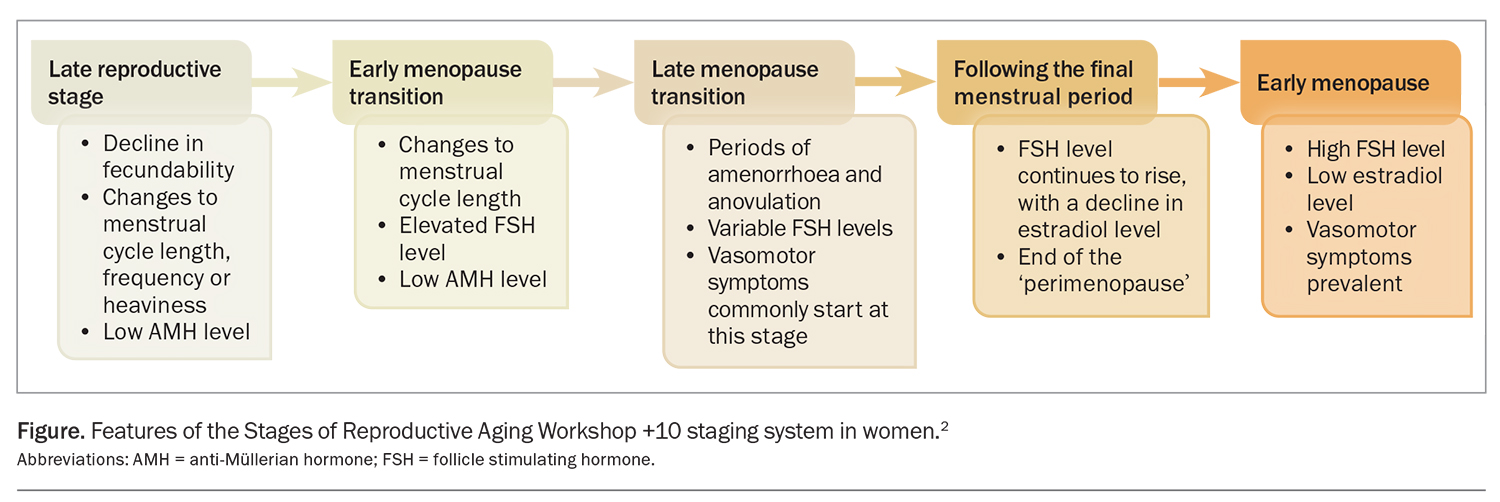

The average age of menopause in Australia is 51 years with a range of 45 to 55 years. Typical symptoms such as vasomotor symptoms last for four to seven years on average. During the early perimenopause, menstrual bleeding abnormalities are common. Heavy, irregular or prolonged menstrual bleeding affects more than 90% of women at least once and nearly 80% at least three times.1 The reason for presentation to a GP can depend on the reproductive stage, nature and severity of symptoms. The reproductive stage is based on the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop +10 (STRAW+10) criteria (Figure).2 The STRAW+10 criteria are divided into five stages:

- late reproductive stage

- early menopausal transition

- late menopausal transition

- following the final menstrual period

- early menopause.

What are some common symptoms of the menopause transition?

Irregular bleeding

Changes in bleeding pattern are a common early symptom of the MT. The changes are most likely related to the anovulation that occurs due to declining sensitivity to oestrogen in the hypothalamus and can occur in up to 51% of women within the first two years of the MT.1 If the bleeding is abnormal in heaviness or duration for the patient, consider investigation with pelvic ultrasound. If there is ultrasound evidence of increased endometrial thickness or the presence of polyps or other intra- or extrauterine masses, referral to a gynaecologist should be made. In the absence of abnormal pathology, treatments can include short-term nonhormonal agents, such as oral tranexamic acid or mefenamic acid, or hormonal agents, such as an oral hormonal contraceptive, short-term oral progesterone during the period of bleeding or a progestogen-releasing intrauterine device (levonorgestrel 19.5 or 52 mg intrauterine drug delivery system sachet).

Vasomotor symptoms

Most women experience hot flushes and night sweats during the MT, with 10 to 30% being affected significantly. These symptoms last for seven years on average but are most frequent in the year around the final menstrual period.3

In those without contraindications, menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is an effective treatment for significant vasomotor symptoms (VMS).4 Combined estrogen and progesterone MHT should be offered to women with an intact uterus to reduce the risk of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer, whereas estrogen-only treatments can be offered to women who have undergone a hysterectomy.5 No single MHT preparation has been shown to be superior to others. However, transdermal estrogen confers a less increased to no risk of venous thromboembolism compared with oral estrogen, although there is little to moderate supporting evidence.6 Micronised progesterone is associated with a higher risk of endometrial cancer compared with synthetic progestogens, but may confer a reduced breast cancer risk than that associated with synthetic progestogens; however, this is also based on low-quality evidence.7,8

In the absence of contraindications, the combined oral contraceptive pill can be considered in the late reproductive stage and early MT for significant VMS, and will also provide contraception and reduce heavy or irregular bleeding.

Genitourinary and sexual symptoms

Genitourinary symptoms affect around one-third of postmenopausal women.1 Women commonly report an increase in urinary urge and frequency symptoms and urinary tract infections (UTIs), as well as discomfort with sexual activity secondary to vaginal dryness, vaginal burning, irritation and bleeding.

A full history should be taken to discern for other possible causes. If a UTI is diagnosed, appropriate antibiotic treatment should be initiated based on sensitivities, and the patient should return for review post-treatment to determine if any of the genitourinary symptoms persist beyond treatment.

In cases of sexual dysfunction, consider other stressors and tensions not directly related to the MT. Antidepressants, such as venlafaxine and gabapentin, can impair sexual function and libido. Referral to a relationship counsellor or psychologist should be considered, especially when the sexual difficulties are bothersome.

Evaluation should include a speculum examination to assess for vulvovaginal dryness, and a cervical screening test can be performed concurrently, if due. If there are concerns about concurrent issues, such as prolapse, dysuria, stress incontinence or rectal urgency or incontinence, consider referral to a gynaecologist (or urogynaecologist, if available) for further examination and work-up, which may include urodynamics and cystoscopy. Referral to a pelvic floor physiotherapist should also be considered.

In cases of significant vaginal dryness, consider prescribing topical estrogen creams, which can be applied two to three times per week at nighttime. Improving vaginal dryness may also improve related concerns, such as dyspareunia and urinary urgency. Nonhormonal vaginal moisturisers may also improve vaginal dryness, although the effects are temporary.

MHT and tibolone are potential options to improve libido, although the evidence of their benefit is limited.9 Testosterone therapy can be considered in cases of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD). If testosterone therapy is being considered, referral to a specialist gynaecologist should be considered to establish a diagnosis of HSDD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-V, initiate therapy, provide appropriate counselling on its side effects and efficacy and to monitor response to treatment.

Psychological symptoms

The MT may be accompanied by changes in sleep and, potentially, in mood. Objective measures of cognition have not revealed significant memory changes.10 Although there is a clear distinction between mood-related changes during the MT and a clinical DSM-V diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD), the group at risk of MDD or elevated depressive symptoms during the MT are those with previous MDD or elevated depressive symptoms.11

Sleep disturbance can occur from the early to late MT and onwards through menopause, particularly in patients with VMS at night. MHT may improve sleep quality in these patients. In the absence of VMS, exploring other factors such as work and relationship stressors could also help guide treatment options.

Nonpharmacological treatments, such as cognitive behaviour therapy, have been shown to improve sleep disturbances significantly during the MT in the absence of a primary sleep disorder diagnosis, compared with standard menopause education.12

Are there any symptoms or aspects of the menopause transition that must not be missed?

Abnormal bleeding

Changes in bleeding patterns are normal in the MT; however, bleeding that becomes more frequent or heavy warrants further investigation. A speculum examination and transvaginal ultrasound are appropriate initial investigations, and any concerning features on examination or initial investigation warrant referral to a gynaecologist for further work-up, which may include endometrial sampling. If there are concurrent concerns about abnormal bleeding and VMS during the MT, a progestogen-releasing intrauterine device could be considered as part of MHT.

Osteoporosis

Changes in circulating sex steroid levels during the MT and postmenopause are associated with changes in bone metabolism, which can subsequently increase the risk of fragility fractures. If there are additional risk factors, such as concurrent autoimmune conditions, this added loss of bone density increases the incidence of fractures. In such cases, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scans should be considered. In patients older than 40 years of age, the Garvan fracture risk calculator (https://www.garvan.org.au/research/bone- fracture-risk-calculator) or fracture risk assessment tool (https://frax.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/index.aspx) can be implemented concurrently or alternatively to guide whether medical therapy is indicated.

Initial management should comprise the optimisation of lifestyle factors, including:

- incorporating regular weightbearing exercises

- ensuring adequate calcium intake

- optimising vitamin D levels, which might require supplementation

- smoking cessation

- moderating alcohol consumption.

If optimising lifestyle factors alone is insufficient to improve osteoporosis, medical therapy should be considered, and this should be managed by an endocrinologist. Depending on an individual’s risk assessment, treatments can include vitamin D and calcium supplementation, MHT, antiresorptive medications and anabolic agents.

Fertility

Pregnancy may still occur in the perimenopausal period, so care should be taken to counsel for this risk and for appropriate contraception to be considered. MHT is not contraceptive, and women and their partners should be counselled accordingly. Contraception should ideally be used until menopause is confirmed, or when a woman has been amenorrhoeic for more than 12 months.13

What initial investigations should be performed or ordered?

In women older than 45 years of age with an intact uterus, the diagnosis of menopause is usually clinical. However, investigation is warranted in certain clinical cases, such as when:

- hysterectomy has been performed previously

- the patient has received or is receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy

- there are concerns about premature (younger than 40 years of age) or early (40 to 44 years of age) menopause.

Investigation includes testing follicle stimulating hormone levels on two occasions, four to six weeks apart. If the levels are elevated on both occasions, a diagnosis of menopause can be confirmed.

What aspects must be considered in managing symptoms of the menopausal transition?

Need for specialist referral

Referral to a gynaecologist should be considered if the patient's symptoms cannot be managed with initial treatments alone, if further investigations are required or when there is concern about a pathological cause for the presenting symptom.

Women with significant menopausal symptoms who are not candidates for MHT can be managed with nonhormonal treatments but should be referred to a gynaecologist if these are not effective.14

Shared care approach

Care can be managed concurrently between a gynaecologist and GP, whereas the treatment requires ongoing specialist input. In the absence or successful treatment of a pathology, and when a patient has achieved adequate symptom control, care can be continued by a GP.

Ongoing maintenance of general health

Considerations for GPs about general health relate to cardiovascular and preventative bone health. Encouraging healthy ageing, via the consumption of a balanced diet and engaging in regular cardiovascular and strength-based exercise, can help minimise the risks of fractures and chronic disease with advanced age. Note that MHT is indicated for the short-term management of VMS and should not be used for the prevention of chronic disease.15 MHT is associated with small but serious health risks. Patients considering the long-term use of combined MHT should be aware of the associated increased risk of breast cancer.16 Starting MHT should be avoided in women older than 60 years of age because of the increased risk of stroke.17

Conclusion

Although symptoms such as VMS and genitourinary symptoms are common in the MT, most women do not seek medical treatment. For those seeking treatment, MHT is the most effective intervention for VMS and topical vaginal oestrogen treatment for genitourinary symptoms. MHT should not be used for chronic disease prevention. For women who present to their GP with MT-related concerns, consider the opportunity to provide holistic preventative advice on the bone and cardiovascular changes that arise with advanced age. Some useful resources for GPs and healthcare professionals are listed in the Box. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Paramsothy P, Harlow SD, Greendale GA, et al. Bleeding patterns during the menopausal transition in the multi-ethnic Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN): a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2014; 121: 1564-1573.

2. Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: 1159-1168.

3. Avis NE, Crawford SL, Greendale G, et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175: 531-539.

4. Sarri G, Pedder H, Dias S, Guo Y, Lumsden MA. Vasomotor symptoms resulting from natural menopause: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of treatment effects from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline on menopause. BJOG 2017; 124: 1514-1523.

5. Santoro N, Roeca C, Peters BA, Neal-Perry G. The menopause transition: signs, symptoms, and management options. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021; 106: 1-15.

6. Rovinski D, Ramos RB, Fighera TM, Casanova GK, Spritzer PM. Risk of venous thromboembolism events in postmenopausal women using oral versus non-oral hormone therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res 2018; 168: 83-95.

7. Tempfer CB, Hilal Z, Kern P, Juhasz-Boess I, Rezniczek GA. Menopausal hormone therapy and risk of endometrial cancer: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel) 2020; 12: 2195.

8. Stute P, Wildt L, Neulen J. The impact of micronized progesterone on breast cancer risk: a systematic review. Climacteric 2018; 21: 111-122.

9. Meziou N, Scholfield C, Taylor CA, Armstrong HL. Hormone therapy for sexual function in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. Menopause 2023; 30: 659-671.

10. Zhu C, Thomas N, Arunogiri S, Gurvich C. Systematic review, and narrative synthesis of cognition in perimenopause: the role of risk factors and menopausal symptoms. Maturitas 2022; 164: 76-86.

11. Bromberger JT, Kravitz HM, Chang YF, Cyranowski JM, Brown C, Matthews KA. Major depression during and after the menopausal transition: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Psychol Med 2011; 41: 1879-1888.

12. McCurry SM, Guthrie KA, Morin CM, et al. Telephone-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women with vasomotor symptoms: A MsFLASH randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176: 913-920.

13. McNamee K, Bateson D. Perimenopausal contraception: a practice-based approach. Aust Fam Physician 2017; 46: 372-377.

14. Hickey M, Szabo RA, Hunter MS. Non-hormonal treatments for menopausal symptoms. BMJ 2017; 359: j5101.

15. US Preventative Services Task Force; Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, et al. Hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal persons: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2022; 328: 1740-1746.

16. Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Aragaki AK, et al. Association of menopausal hormone therapy with breast cancer incidence and mortality during long-term follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized clinical trials. JAMA 2020; 324: 369-380.

17. Lisabeth L, Bushnell C. Stroke risk in women: the role of menopause and hormone therapy. Lancet Neurol 2012; 11: 82-91.