A tailored approach to managing menopause

When treating women around menopause, consideration of each woman's reproductive status and subsequent effects to her health, as well as clinical history and assessment findings, is important. Lifestyle changes are first-line approaches to management, regardless of menopausal status. Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is effective in managing menopause symptoms in women, but GPs should be aware of the risks of long-term use and manage patients accordingly. Women in whom MHT is contraindicated should be offered nonhormonal therapy.

Menopause is a clinical diagnosis in older women, defined by an absence of menstrual periods for 12 consecutive months. After this, women are considered postmenopausal. In young women who experience amenorrhoea, premature ovarian insufficiency should be considered a possible diagnosis for her symptoms, and biochemical assessment is needed to confirm a diagnosis.

Perimenopause is defined from the onset of irregular periods until 12 months after the final menstrual period, specifically with at least a seven-day difference between cycle lengths.1 Towards the end of the reproductive years, fertility diminishes and ovarian activity becomes erratic, leading to potential menstrual irregularity and the development of symptoms representing both low and high hormonal levels. Anovulatory cycles (i.e. absence of ovulation) become more frequent and can lead to irregular periods, increasing the risk of endometrial proliferation, hyperplasia and possible endometrial cancer. Ovulation may occur twice in a menstrual cycle, the second time being during a period (known as LOOP; luteal out of phase ovulation).2

Menopause management of each woman entails the development of an individualised treatment plan following assessment and investigation, primarily by an appropriate and thorough history and examination. Importantly, a woman’s menopausal status influences her management; therefore, understanding the stages of menopause, associated symptoms and treatment options is important to appropriate and effective management. Using two example cases, this article highlights the importance of an individualised approach to managing women in the menopause.

Case 1. A 49-year-old woman with perimenopausal symptoms

Perimenopause is a period that may be without any disruption to a woman’s quality of life, but for many women it is a time of change in wellbeing, mood and coping capacity as well as menstrual irregularity and physical symptoms. Some women will experience increasing premenstrual symptoms, heavy and/or erratic periods and abnormal bleeding. Oestrogen levels at this time may be quite high, and may cause breast tenderness, bloating, anxiety or headaches.2 Women may also have low oestrogen levels, leading to vasomotor symptoms, including night sweats and flushes that are intermittent or regular.

Presentation

Ms A is a 49-year-old secondary teacher who is divorced with two adult children aged 21 and 23 years. She has experienced irregular periods for eight months and had a recent heavy period with clots lasting 10 days after two months of amenorrhoea. She has increasing anxiety and stress levels with less capacity to manage her life. Her sleep pattern is disturbed; she is waking up at night feeling hotter than normal and is tired.

She has a new partner and is concerned about using appropriate contraception. Her general health is good, she exercises regularly, has a good diet and is not on any medications, except for vitamin D 1000 IU per day. She is a nonsmoker and drinks alcohol rarely. There is no significant medical or surgical history except for the delivery of her two children by caesarean section. Her mother had morbid obesity and severe hypertension, and died at the age of 78 years of a heart attack. Her father is 82 years old and has type 2 diabetes, but is otherwise well.

General and gynaecological examination reveals her uterus is bulky, similar in size to a nine-week pregnancy. She has no other major abnormalities.

Assessment

The first steps are assessing Ms A and determining the differential diagnoses. The following issues should be considered with regard to Ms A’s symptoms, history and examination:

- irregular periods

- heavy menstrual bleeding

- wakefulness

- anxiety and stress

- increased body heat

- new relationship

- contraception

- bulky uterus.

Based on Ms A’s symptoms and history, a number of differential diagnoses should be considered.

- Perimenopause – her age and the symptom complex are consistent with the perimenopause.

- Endometrial hyperplasia – heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) with clots after a few months of amenorrhoea may be associated with a thickened endometrium. Also, anovulatory cycles during the perimenopause lead to endometrial proliferation and thickening. This is of more concern in women with obesity, as testosterone is metabolised to oestrogen in peripheral fat leading to added oestrogen stimulation.

- Adenomyosis or fibroids – both can cause a bulky uterus and HMB.

- Spontaneous abortion/miscarriage – she experienced HMB after a period of amenorrhoea. She is also concerned about contraception.

- Sleep disorder – she is wakeful and tired.

- Anxiety disorder – mood disorders are common or recur in women in their 40s and 50s due to changing hormone levels.

- Thyroid dysfunction – may develop around the perimenopausal period.

- Diabetes – may cause flushing.

Investigations

Given the above differential diagnoses, the following investigations should be done:

- full blood examination

- pregnancy test

- thyroid function test

- iron studies

- fasting blood sugar level

- ultrasound transvaginal (preferably when the period is ceasing or immediately after, as the endometrium will be at its thinnest).

Hormone level tests are not routinely recommended in the perimenopause because they are very variable at this time and unlikely to assist in the diagnosis. For instance, it is possible to see estradiol levels suggestive of ovulation one week and elevated follicle stimulating hormone level the next. Occasionally, when there are no discernible cycles or a woman has had a hysterectomy, a series of hormone level tests may be required. If a diagnosis is made on a single hormone level in the perimenopause, inappropriate treatment may be prescribed.

Management

Ms A’s management should start with lifestyle recommendations, including:

- eating nutritious foods

- maintaining a regular exercise program

- having regular routine screening and medical examinations, including blood pressure and breast examinations

- having a cervical screen test

- regular mammograms

- having regular screening for cardiovascular disease and bone health.

Perimenopausal irregular bleeding is common but an assessment of the endometrial thickness on ultrasound is important to determine whether Ms A requires an endometrial biopsy or hysteroscopy and curettage in order to exclude endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma. There are a number of treatment options to manage both her irregular heavy periods and her contraceptive needs. These include the combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill or ring, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG IUD) and the 4 mg drospirenone pill. Stabilising her cycle and providing contraception may help to relieve Ms A’s anxiety and stress. Prescribing estradiol-containing COCs in the perimenopause can help treat heavy and/or irregular periods, provide contraception and relieve hot flushes and sweats. They also have lesser effects on haemostasis, fibrinolysis markers, lipids and carbohydrate metabolism.3 Although the LNG IUD provides effective contraception and reduces menstrual bleeding over time, it has no effect on vasomotor symptoms, and additional oestrogen is required with its use, usually as an estradiol patch or gel.

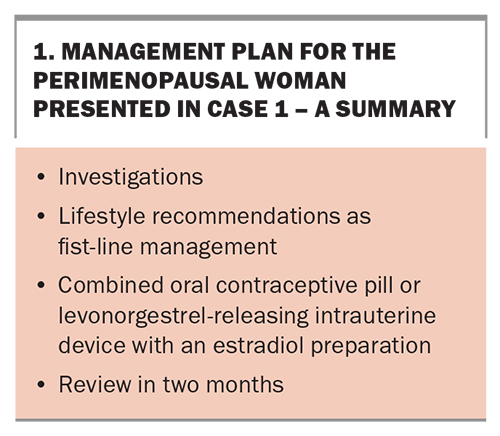

If all of Ms A’s investigation results are normal except for the bulky uterus found on the ultrasound and examination, determine the most appropriate treatments available. Ms A should be asked to diarise her symptoms and bleeding to assess improvement and be given a copy of her treatment plan, summarised in Box 1.

Case 2. A 53-year-old woman with postmenopausal symptoms

The term menopause refers to the final menstrual period, so the diagnosis is always retrospectively made after 12 months of amenorrhoea. Once a woman is 12 months past her final menstrual period, she is postmenopausal for the rest of her life. Commonly reported symptoms include:

- vasomotor symptoms of hot flushes and sweats usually at night, with sleep disturbance

- muscle and joint aches and pains

- anxiety and irritability

- decreased concentration

- loss of libido

- vaginal dryness and other genitourinary symptoms related to lack of oestrogen, including painful intercourse (dyspareunia)

- fatigue and tiredness

- crawling sensations on the skin (formication)

- reduced wellbeing and diminished quality of life.

After the menopause, women are at increased risk of developing heart disease, osteoporosis, central adiposity, genitourinary disorders and mood disorders.

Presentation

Ms B is a 53-year-old company director who presents with hot flushes, night sweats, sleep disturbance, tiredness, difficulty with word finding, reduced libido and some dyspareunia due to vaginal dryness. Her last menstrual period was at 51 years and she has had no further spotting, staining or bleeding. Her last cervical screen was 12 months ago and her mammogram is due in 2023. Her last blood test revealed her fasting cholesterol level was 6.3 mmol/L but her cholesterol/HDL ratio was normal.

Her exercise routine has suffered and her alcohol consumption increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and she has gained weight. She stopped smoking five years ago because of regular bronchitis. Her body mass index is 29 kg/m2 and her blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg. A history and examination reveal no other abnormalities. She lives alone and has no children, but has a partner who lives nearby. Her mother has osteoporosis and her father has had prostate cancer and hypertension, all controlled.

Her symptoms are embarrassing her, especially when she is presenting in important meetings, and her self-esteem, confidence and body image are diminished. She has tried a number of over-the-counter menopause products but none have been effective in relieving her symptoms. She wants to try menopausal hormone therapy (MHT, previously known as hormone replacement therapy [HRT]).

Investigations

Ms B should undergo general blood tests including cholesterol, glucose, thyroid, calcium and vitamin D levels and iron studies, if these have not been performed within the last 12 months. Her screening tests should also be checked to ensure these are up to date.

Assessment

Menopausal hormone therapy

In a postmenopausal woman who has not had either a premature or early menopause, the lowest effective dose of MHT is prescribed. The usual advice is to start at a low dose and increase at a later consultation if there has been inadequate symptom relief.

Within the first one to two years after the final menstrual period, sequential/cyclical MHT therapy is recommended, comprising continuous oestrogen plus progestogen for 12 to 14 days per cycle to ensure a regular bleed occurs. Most women after that time prefer continuous oestrogen– progestogen therapy to avoid further bleeding and give greater endometrial protection. If a woman has had a hysterectomy, then she requires oestrogen-only therapy, as the role of progestogen is primarily to protect the endometrium from the normal proliferation of oestrogen.

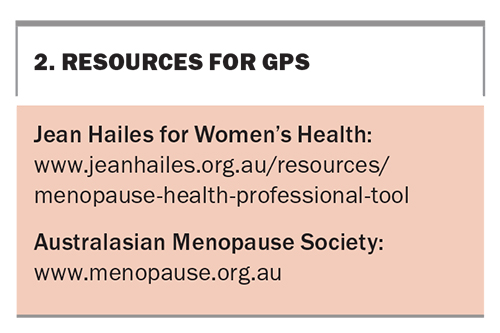

MHTs include various oestrogen– progestogen preparations, both oral and transdermal, the steroid tibolone, tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) comprising a conjugated oestrogen and bazedoxifene combination, and individual oestrogen-only and progestogen-only products. An up-to-date list is available online at: www.menopause.org.au/hp/information-sheets/ams-guide-to-equivalent-mht-hrt-doses. Other resources on menopause are listed in Box 2.

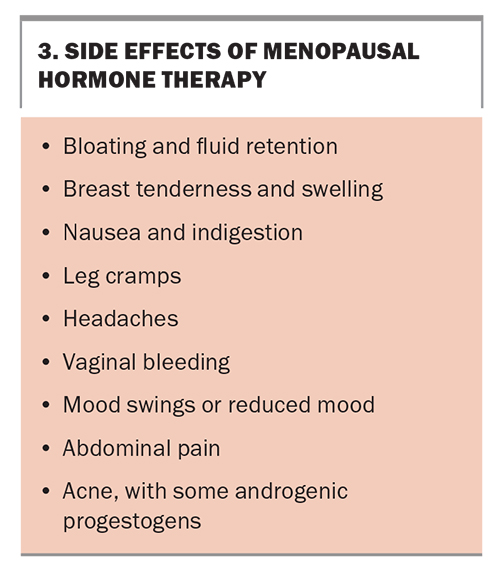

Side effects from MHT are common (Box 3) but usually settle within the first few months of therapy. Breakthrough bleeding within the first six months of therapy is not considered abnormal unless it is prolonged. Any breakthrough bleeding after that time should be investigated for a cause such as an endometrial polyp.

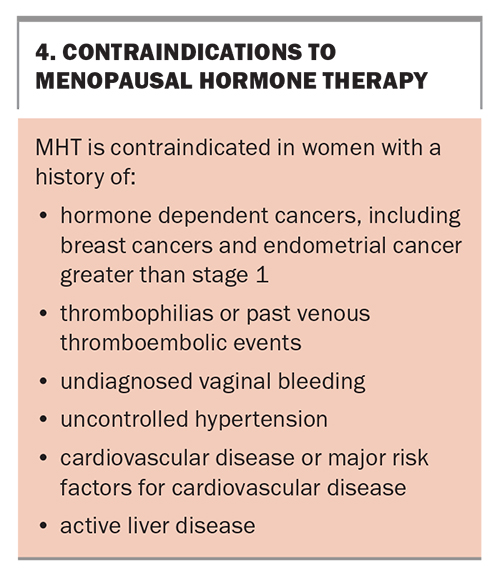

Nonhormonal prescription therapies or referral to a menopause specialist or clinic should be recommended to women in whom MHT is contraindicated. Contraindications for MHT are listed in Box 4. Nonhormonal prescription therapies include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor antidepressants (SNRIs), gabapentin or pregabalin (both used for chronic pain or as antiepileptic medications) and clonidine (an antihypertensive that has been used for many years). Oxybutynin (used for an overactive bladder) has also been used for vasomotor symptoms.4 These agents have shown a reduction of vasomotor symptoms in research studies and all are used off-label for this purpose. Other therapies that have shown some reduction in vasomotor symptoms include cognitive behavioural therapy and hypnotherapy.

Risks of MHT

MHT increases the risk of breast cancer, although the level of risk depends on the therapy prescribed, the dose and duration of therapy and the age of the woman. Oestrogen-only therapy is associated with a lower risk than combined therapy. The risks are lower in women aged 50 to 59 years, and increase with ongoing use. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study showed that the risk of breast cancer increased by eight additional breast cancer cases per 10,000 for women on oestrogen–progestin therapy for five years or more.5 Results from two nested case-control studies showed an additional three cases per 10,000 women years for oestrogen-only therapy and nine additional cases per 10,000 women years for oestrogen–progestogen therapy in women near the menopause and up to five years’ use. The risk decreased after stopping MHT.6 However, a long-term follow up of women in the WHI study showed a reduced incidence of breast cancer in the oestrogen-only group.7 Progestogens, progesterone and dydrogestrone have a lower risk of breast cancer compared with medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethisterone and LNG, which are associated with a higher risk.6

The risk of breast cancer in women with a positive family history is the same whether they are on MHT or a nonuser. The risk is increased in women with obesity but not compounded if on MHT. Importantly, there is no increased breast cancer risk for women using vaginal oestrogen-only therapy.

The risk of thromboembolism is increased by two to three per 1000 women years with oral MHT compared with one per 1000 woman years in those who do not take MHT. There is no increase in thromboembolic risk with transdermal MHT use; however, the data only included up to medium doses. Women with obesity and those who smoke have higher rates of venous thromboembolism which is increased further if they take oral MHT.8

Cardiovascular disease risk is not increased in women using MHT within 10 years of the menopause. It is associated with age at which MHT is commenced and increasing age. Overall, protection from heart disease and reduced mortality was seen in women prescribed MHT at 50 to 60 years of age or within 10 years of their final menstrual period.9

Management

As with Ms A, lifestyle recommendations are first-line management strategies. For Ms B these include:

- assessment of diet with recommendations for healthy eating

- referral to a dietitian to assess her diet if she wants to lose weight

- recommendation of an exercise program to suit her lifestyle and encouragement of daily exercise

- recommendation to reduce her alcohol consumption, which may also lead to weight loss

- check of her emotional health as she has a high-level position that requires good memory and concentration, is working from home and lives alone and was isolated during COVID-19 lockdowns.

As it has been two years since Ms B’s final menstrual period, a continuous regimen of oestrogen–progestogen therapy is suitable. The risks of thrombosis are lower with a transdermal oestrogen product and progesterone use.

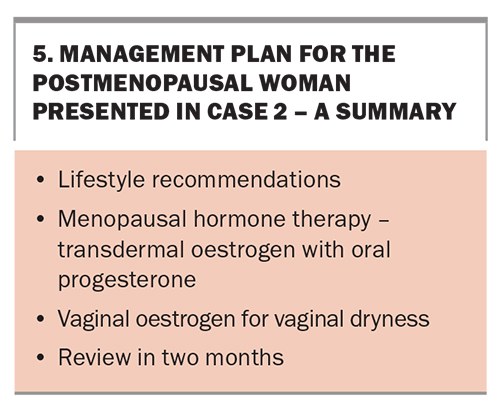

Vaginal oestrogen, either as a tablet, pessary or cream, is suitable to help Ms B’s vaginal dryness. Inserting the oestrogen into the lower-third of the vagina is recommended because of the pudendal and perineal vessels supplying the lower pelvis, with lower levels of oestrogen absorption in the lower-third compared with the upper two-thirds.10 A summary of Ms B’s management plan is presented in Box 5.

Conclusion

Menopause treatment options vary with the phase at which a woman presents – in the perimenopause, the immediate postmenopause or some years later. Her symptom complex, past and family history and her own preferences will guide her treatment. Informing the woman of the risks and benefits enables her to decide what MHT she wishes to trial. If MHT is contraindicated, nonhormonal therapies are effective and should be offered. Above all, it is important to tailor the therapy to meet each individual woman’s needs. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Farrell has received consultation fees from Vifor Pharma and Theramex; presented lectures for Vifor Pharma, Besins Healthcare and Theramex; is a Gynaecology Consultant to Medical Panels Victoria; and is Medical Director and Board Member for Jean Hailes for Women.

References

1. Harlow S, Gass M, Hall J, et al; STRAW 10 Collaborative Group. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. Menopause 2012; 19: 387-395.

2. Hale GE, Hughes CL, Burger HG, Robertson DM, Fraser IS.Atypical estradiol secretion and ovulation patterns caused by luteal out-of-phase (LOOP) event sunder lying irregular ovulatory menstrual cycles in the menopause transition. Menopause 2009; 16: 50-59.

3. Christin-Maitre S, Laroche E, Bricaire L. A new contraceptive pill containing 17B-oestradiol and nomegestrol acetate. Womens Health (Lond) 2013; 9: 13-23.

4. Leon-Ferre R, Novotny P, Wolfe E, et al. Oxybutynin vs placebo for hot flashes in women with or without breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial (ACCRU SC-1603). JNCI Cancer Spectr 2020; 4: pkz088.

5. Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288: 321-333.

6. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer: nested case control studies using the QResearch and CRPD databases. BMJ 2020; 371: m3873.

7. Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Aragaki AK, et al. Association of menopausal hormone therapy with breast cancer incidence and mortality during long-term follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized clinical trials. JAMA 2020; 324: 369-380.

8. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using QResearch and CRPD databases. BMJ 2019; 364: k4810.

9. Boardman HM, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; (3): CD002229.

10. Eden J. Vaginal atrophy and sexual function. Health Ed Expert 2017; 15.