Night-time mysteries – unmasking parasomnias in adult sleep

Parasomnias are classified based on the sleep stage in which they occur: rapid eye movement (REM) sleep or non-REM sleep. They can lead to unintentional injuries; therefore, identifying simple ways to prevent harm is paramount. REM sleep behaviour disorder may be a prodrome to neurodegenerative conditions and these patients should be referred to a sleep physician accordingly.

- Parasomnias are categorised according to the stage of sleep in which they occur: rapid eye movement (REM) sleep or non-REM (NREM) sleep.

- Often seen in children, NREM parasomnias can persist into adulthood.

- The safety of the individual and their bed partner (if applicable) is paramount and strategies should be instigated to minimise unintentional injury.

- Pharmacotherapy can be useful in certain cases of NREM parasomnia, but behavioural and preventive strategies including stress reduction may be sufficient.

- A sleep physician referral is suggested if the diagnosis is in doubt or if significant injuries or consequences are occurring.

- REM sleep behaviour disorder is often associated with neurodegenerative diseases; seeking sleep and neurology opinions is therefore advised.

Parasomnias are abnormal behaviours of arousals arising from sleep, mostly of motor origin, with varying severity and potential consequences. They occur not infrequently in both children and adults and can lead to significant distress in both the individual and caregivers or family members, as well as leading to a risk of unintentional injuries. This article summarises the most common parasomnias in adults seen in general practice and sleep clinics and provides practical points regarding their management.

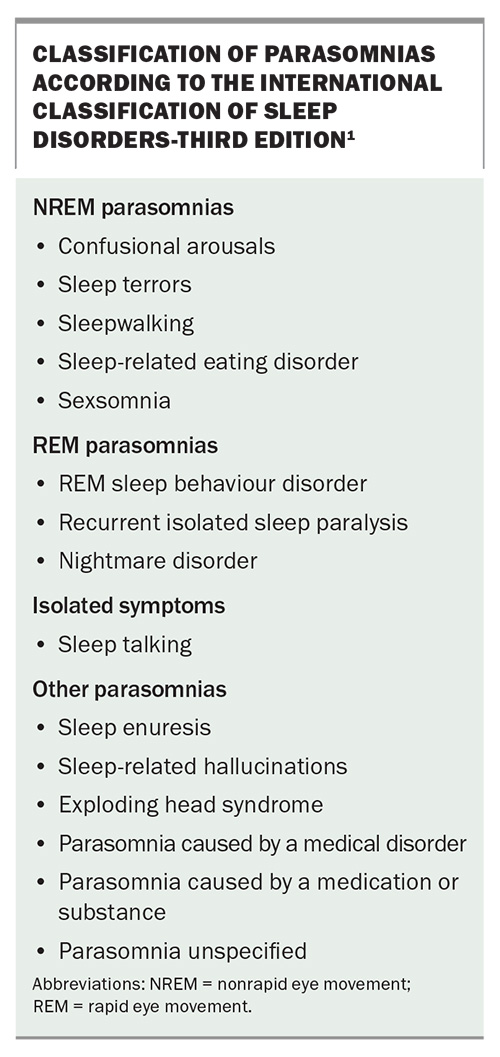

Parasomnias are classified according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-Third Edition (ICSD-3) (Box).1 They are categorised based on the stage of sleep in which they occur: rapid eye movement (REM) sleep or non-REM (NREM) sleep. NREM parasomnias occur mainly during slow-wave sleep (stage N3 of sleep) and are seen more often in children than in adults. Most affected children will grow out of the behaviour but symptom continuation into adulthood can prove problematic, and adults may seek advice regarding management and an opinion from a sleep physician. REM parasomnias (in particular REM sleep behaviour disorder [RBD]) tend to occur in older adults and can be associated with neurological disorders (especially neurodegenerative disease) such as Parkinson’s disease and other comorbidities. Parasomnias are often associated with injury to the individual or the bed partner, ranging from mild to severe, and can also be associated with forensic consequences.2 There can be overlap between NREM and REM parasomnias, whereby the classic features of both occur concurrently in a spectrum.

NREM parasomnias

NREM parasomnias tend to occur in the transition between the slow-wave sleep (stage N3) and wake stages and are classified by varying descriptors, depending on the subsequent behaviours (Box).1 Confusional arousals, sleep terrors and sleepwalking occur most frequently and can be thought of as parasomnias along a continuum of similar symptomatology. The complex behaviours associated with NREM parasomnias are typically automatic behaviours, indicating that conscious awareness of the surroundings is absent. The lack of conscious decision-making is a feature that can often be established from witnesses. This may be particularly important within a forensic context. Other behaviours resulting from incomplete awakening from NREM sleep include acts of primal driven behaviour such as eating and, as observed among adults, performing sexual acts.

NREM parasomnias mainly occur in early childhood but can continue into adulthood, with a lifetime prevalence of about 7% (5% prevalence in children and 1.5% prevalence in adults found in a recent meta-analysis).3 NREM parasomnias in adults may have associations with other sleep disorders and comorbid mental health disorders.4 As many NREM parasomnias have a genetic propensity, it is important to take a precise family history. Sometimes parasomnias may seem to start in adulthood, with medical help sought for the first time at that stage, but there may be a personal or family history in childhood that the patient is unaware of until further information is gained from their parents or childhood caregivers. The individual usually has amnaesia to the events, but not always, and the behaviours can be distressing for others to witness. There may be triggers leading to an increased frequency of events, for instance sleep deprivation, noise, stress, excess alcohol consumption and other psychosocial issues.

Sleep-related eating disorder often occurs in early adulthood and consists of recurrent episodes of involuntary eating during sleep. The diagnosis of sleep-related eating disorder must be distinguished from night eating syndrome. Typically, identification of the items eaten (e.g. non-food items or abnormal combinations of foods) may give an indication of whether the eating was intentional (night eating syndrome) or unintentional (sleep-related eating disorder), as will the presence of recall or amnaesia about the eating.5

Sexsomnia, or sleep sex, is the term given to the occurrence of sexual acts as part of an incomplete arousal from sleep and can include a wide spectrum of behaviours, followed by amnaesia of these acts. It occurs mostly in men, is rare and may have forensic consequences.6

Investigation and diagnosis

Diagnosis of NREM parasomnia can usually be made with a precise clinical history from the patient and witnesses. However, if there is any doubt regarding the diagnosis, or if certain atypical features are present (including adult-onset symptoms), then an overnight sleep study is required.7 An attended, in-laboratory sleep study (with accompanying audio and video recording) should be used, as opposed to a home sleep study, so that detailed analysis can be performed of the sleep architecture and to exclude any other coexisting sleep disorders contributing to sleep fragmentation.

Any unusual behaviour or sudden awakenings from stage N3 sleep are reviewed to examine the type of activity occurring during these events. Typically, behaviours usually seen in the home environment do not occur as profoundly during a sleep study; however, certain patterns are still suggestive of NREM parasomnias even if no gross movement abnormalities occur in the laboratory. Frequent abrupt awakenings from stage N3 sleep can be supportive of a diagnosis of an NREM parasomnia. During these events, patients may wake, vocalise or appear confused and look around the room or at the monitoring equipment and then return to sleep soon after.7 These actions in the sleep laboratory are usually much less significant than those noted by bed partners or family members, and for this reason, keeping a sleep diary of events and bringing a family member to the appointment are useful adjuncts to confirm the diagnosis.

An important differential diagnosis for unusual behaviour during sleep is sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy, also known as nocturnal epilepsy. This may appear as arousals from sleep, vocalisation and unintentional movements, which are often stereotypical in nature. Careful scrutinisation of EEG results and behaviours during these events is required because there are subtle distinctions that can help confirm the correct diagnosis.8,9 These behaviours can occur during any sleep stage, not just in stage N3, as seen in NREM parasomnias. Validated questionnaires have been used to help confirm the diagnosis of a parasomnia and to help distinguish between parasomnias and sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy.7,10 Recently, the introduction of home video-EEG monitoring has enabled the study of patients for much longer periods than in the hospital setting (usually seven days or more), often with more extensive EEG recording. This has shown a high rate of capturing events and reaching a diagnosis.11,12

There is evidence that individuals who are predisposed to parasomnias may have different sleep microarchitecture, compared with others who are not predisposed to parasomnias, and may possibly have NREM sleep instability.13 Analysis of the sleep EEG of these individuals has shown that a particular marker of sleep instability called cyclic alternating pattern is more prevalent, and lower delta activity (a marker of the intensity of slow-wave sleep) in the initial NREM sleep cycle has been consistently reported.13,14

Management

Nonpharmacological approaches

The management of NREM parasomnias in adults can be highly variable, depending on the frequency, severity and consequences of the activities occurring. Although no specific international guidelines for the management of NREM parasomnias have been published to date, there are thorough clinical practice reviews providing excellent discussion of the management of these disorders.7,15 Behavioural and psychological treatments may be effective in many cases, particularly in minimising any triggering factors.16

Identifying simple ways to prevent harm or injury is paramount: for example, locking the house at night and having someone else hide the key, and ensuring windows and balconies are inaccessible. Explaining the nature of the disorder and its natural history may reassure the patient. Treating any associated sleep-disordered breathing and other sleep disorders, ensuring a regular sleep–wake pattern, educating bed partners, avoiding sleep deprivation, minimising shift work (where possible), reducing alcohol consumption and reducing stress may all help minimise the frequency of events.

Pharmacological treatments

Pharmacotherapy may be required in some cases (e.g. if an individual who sleepwalks finds themselves in potentially dangerous situations). In such cases, referral to a sleep physician would be recommended for a full sleep assessment and to guide management. Historically, long-acting benzodiazepines, in particular clonazepam, have been prescribed to minimise parasomnias; however, it remains a difficult balance to initiate such a long-term medication with the known side effect profile, especially if the patient is a young adult and when it may not be required every night.

There is a lack of rigorous scientific randomised controlled trials to support the use of medication in NREM parasomnias, because studying the disorder can be challenging. Current evidence is limited to case series, and there is only one study thus far with objective video-recording data in a small cohort showing clonazepam to be effective.17-19 Other agents such as antidepressants have been utilised, but the evidence is inconclusive and limited and, therefore, antidepressants are not suggested as first-line pharmacotherapy. Hence, if behavioural strategies (which might include hypnosis or cognitive behaviour therapy) and avoidance of triggers can help to alleviate the need for regular pharmacotherapy, then that is often preferred.17,20

Short-term medication may, however, be prescribed if, for instance, the patient is travelling and sleeping in an unusual environment or if the frequency of events has increased because of a particular stressor. The frequency of events then often settles down and long-term medication is not always needed. However, if the parasomnia has led to a significant injury or adverse outcome, which could include a medicolegal situation and its inherent repercussions, then long-term pharmacotherapy must be suggested for the safety of the individual and others.

REM parasomnias

The most clinically important REM parasomnia seen by sleep physicians is REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD) (Box), in light of the consequences that can occur and the neurodegenerative associations that can present in individuals with this disorder.1

REM sleep behaviour disorder

During normal REM sleep, there is generalised muscle atonia throughout the body, except for in the diaphragm, which maintains ventilation. REM sleep is most often associated with more complex, narrative-like dreams that tend to occur more in the second half of the night.

In RBD, the usual muscle atonia is not maintained and, as a result, abnormal movements can occur that often reflect dream content, known as dream enactment behaviour. These can be violent in nature and can result in injury to either the patient or more often the bed partner. The patient can usually recall the content of the dream (unlike in NREM parasomnias) and it often has a frightening or violent theme, with the individual trying to defend themselves or others, which may result in significant injuries.21 It is not unusual for the patient to fall out of bed, but they will usually stay within the confines of the bedroom (unlike those who sleepwalk, who may move into different rooms).

There is, however, a spectrum, and dream enactment behaviour can range from minor movements of the fingers through to full body movements with vocalisations. Compared with NREM parasomnias, the behaviours tend to occur later in the night when REM sleep is more prevalent. The prevalence of RBD is estimated to be 0.5 to 2.0% of the general population, with the highest incidence being in men aged over 50 years.22

RBD is known to be associated with the alpha-synucleinopathies, particularly Parkinson’s disease and less often with dementia with Lewy bodies and multiple system atrophy. It is more common in men than women. The conversion rate from identification of RBD to developing neurodegenerative disease has been documented at 34, 82 and 97% after five, 10 and 14 years, respectively.22 Thus, identification of RBD may be important as an early sign of neurodegeneration. It has been suggested that the previously named ‘idiopathic RBD’ should be renamed to ‘isolated RBD’ to illustrate the high conversion rate seen in this group, and that it is a likely prodrome of one of the neurodegenerative conditions, rather than an idiopathic condition.23 Once a diagnosis of RBD has been considered, it is prudent to enquire about any subtle early neurological symptoms.

RBD may have causes other than neurodegenerative disease, as detailed below.

- There is a link between RBD, mood disorders and the use of antidepressants, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.24

- Recent studies have confirmed a link between RBD and post-traumatic stress disorder.25,26 Although there are commonalities between RBD and mental health disorders, there are different pathophysiological mechanisms at play.27

- Autoimmune encephalitis, especially anti-IgLON5 disease, can cause RBD.28

- Genetic markers may be implicated in both neurodegeneration and RBD.29

- A high rate of RBD is seen in people with narcolepsy, especially type 1 narcolepsy.30

Investigation and diagnosis

An attended overnight sleep study, with accompanying audio and video recording, is required to confirm the presence of REM sleep without atonia. History alone is not sufficient to confirm a diagnosis of RBD. Additional electromyogram monitoring compared with a standard sleep study is often added to detect small changes in muscle activity. During normal REM sleep, muscle activity is suppressed, whereas in REM sleep without atonia, there is increased muscle activity, which may correspond to visible body movements. As with NREM parasomnias, dream enactment behaviour (the visible feature of RBD) is often less pronounced during a sleep study than at home; however, patterns of increased electromyogram activity during REM sleep can confirm REM sleep without atonia without significant behaviours occurring. REM sleep without atonia is the hallmark of RBD and is required to confirm a diagnosis. It is also important to look for signs of other sleep disorders, in particular obstructive sleep apnoea, as this may be associated with dream enactment behaviour.

The ICSD-3 requires the following diagnostic criteria for RBD:

- repeated episodes of sleep-related vocalisation and/or complex motor behaviours

- behaviours are documented by polysomnography to occur during REM sleep or, based on clinical history of dream enactment, are presumed to occur during REM sleep

- polysomnography shows REM sleep without atonia

- absence of epileptiform activity during REM sleep, unless RBD can be clearly distinguished from any concurrent REM sleep-related seizure disorder

- the disturbance is not better explained by another sleep disorder, medical or neurological disorder, medication or substance use.1

Management

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has recently published a systematic review, a meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines for the management of RBD.31,32 After the diagnosis of RBD has been confirmed, as in NREM parasomnias, management prioritises the safety of the patient and their bed partner, if applicable. This can be achieved by simple measures in the bedroom, including:

- ensuring that there are no sharp objects on the bedside tables or next to the bed

- lowering the bed height or sleeping on a mattress on the floor if the patient is regularly falling out of bed

- ensuring that there is a barrier (e.g. pillows) between the patient and the bed partner

- having the patient sleep in a sleeping bag within the bed to restrain them somewhat from movement

- sleeping in a separate room to their partner.

A motion sensor or pressure-sensitive alarm that wakes the patient when they move before larger, undesired movements occur could be considered.

Treating concurrent sleep disorders, in particular obstructive sleep apnoea, which can be more prevalent in REM sleep and can trigger arousals by apnoeic episodes, may reduce the frequency of events. Caution needs to be taken regarding continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) equipment, in case the patient has sudden movements and becomes caught up in the cables or tubing. It may be necessary to have someone present to monitor the patient if CPAP is considered.

Pharmacological treatments

Pharmacotherapy is often required, with low-dose clonazepam or melatonin predominantly used. Large randomised controlled trials for RBD are lacking, and mainly small case series have been described regarding therapy. Clonazepam has been used for RBD for decades and, if considered, should be commenced at a low dose of 0.25 mg before bed, and titrated as required, taking into account its well-known side effects, especially in older patients.33 Melatonin has gained interest in recent years, with short-acting melatonin preferred, although longer-acting formulations in theory should provide better duration of therapy to cover the later REM periods of the night.34 However, small randomised controlled trials of melatonin have failed to show benefit for RBD, and larger trials are needed to confirm or dispute its utility.32,35 Switching or ceasing antidepressants (if appropriate) could be considered to improve symptoms if the antidepressants are thought to be causative.

A referral to a sleep physician is suggested for anyone with a history of dream enactment behaviour, and a referral to a neurologist with a particular interest in this area is recommended. Once the diagnosis of RBD is confirmed, discussion with the patient of the association of RBD and neurodegeneration should be considered carefully as this may not be appropriate for all patients. Even if the patient is asymptomatic for a neurodegenerative disease at the time of diagnosis of RBD, many neurologists will continue to see them regularly to assess for subtle initial neurological symptoms.

Conclusion

Parasomnias are not uncommon in the adult population and can lead to significant distress and injuries to the patient and their bed partner, if applicable. The safety of the individual and their bed partner is the most important concern. A sleep clinic referral should be considered to confirm the diagnosis and manage therapy, in particular if injuries have occurred. Additionally, RBD may be a prodrome to neurodegenerative conditions and patients should be referred accordingly. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

2. Morrison I, Rumbold JM, Riha RL. Medicolegal aspects of complex behaviours arising from the sleep period: a review and guide for the practising sleep physician. Sleep Med Rev 2014; 18: 249-260.

3. Stallman HM, Kohler M. Prevalence of sleepwalking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0164769.

4. Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Priest RG. Night terrors, sleepwalking, and confusional arousals in the general population: their frequency and relationship to other sleep and mental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60: 268-276; quiz 277.

5. Idir Y, Oudiette D, Arnulf I. Sleepwalking, sleep terrors, sexsomnia and other disorders of arousal: the old and the new. J Sleep Res 2022; 31: e13596.

6. Holoyda B. Forensic implications of the parasomnias. Sleep Med Clin 2024; 19: 189-198.

7. Mainieri G, Loddo G, Provini F, Nobili L, Manconi M, Castelnovo A. Diagnosis and management of NREM sleep parasomnias in children and adults. Diagnostics (Basel) 2023; 13: 1261.

8. Tinuper P, Bisulli F, Cross JH, et al. Definition and diagnostic criteria of sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy. Neurology 2016; 86: 1834-1842.

9. Montini A, Loddo G, Baldelli L, Cilea R, Provini F. Sleep-related hypermotor epilepsy vs disorders of arousal in adults: a step-wise approach to diagnosis. Chest 2021; 160: 319-329.

10. Derry CP, Davey M, Johns M, et al. Distinguishing sleep disorders from seizures: diagnosing bumps in the night. Arch Neurol 2006; 63: 705-709.

11. Wong V, Hannon T, Fernandes KM, Freestone DR, Cook MJ, Nurse ES. Ambulatory video EEG extended to 10 days: a retrospective review of a large database of ictal events. Clin Neurophysiol 2023; 153: 177-186.

12. Nurse ES, Perera T, Hannon T, Wong V, Fernandes KM, Cook MJ. Rates of event capture of home video EEG. Clin Neurophysiol 2023; 149: 12-17.

13. Guilleminault C, Kirisoglu C, da Rosa AC, Lopes C, Chan A. Sleepwalking, a disorder of NREM sleep instability. Sleep Med 2006; 7: 163-170.

14. Gaudreau H, Joncas S, Zadra A, Montplaisir J. Dynamics of slow-wave activity during the NREM sleep of sleepwalkers and control subjects. Sleep 2000; 23: 755-760.

15. Malkani RG. Parasomnias in adults. BMJ Best Practice. 2024. Available online at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/573 (accessed March 2025).

16. Mundt JM, Schuiling MD, Warlick C, et al. Behavioral and psychological treatments for NREM parasomnias: a systematic review. Sleep Med 2023; 111: 36-53.

17. Drakatos P, Marples L, Muza R, et al. NREM parasomnias: a treatment approach based upon a retrospective case series of 512 patients. Sleep Med 2019; 53: 181-188.

18. Schenck CH, Milner DM, Hurwitz TD, Bundlie SR, Mahowald MW. A polysomnographic and clinical report on sleep-related injury in 100 adult patients. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146: 1166-1173.

19. Lopez R, Barateau L, Chenini S, Rassu AL, Dauvilliers Y. Home nocturnal infrared video to record non-rapid eye movement sleep parasomnias. J Sleep Res 2023; 32: e13732.

20. Becker PM. Hypnosis in the management of sleep disorders. Sleep Med Clin 2015; 10: 85-92.

21. St Louis EK, Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder: diagnosis, clinical implications, and future directions. Mayo Clin Proc 2017; 92: 1723-1736.

22. Galbiati A, Verga L, Giora E, Zucconi M, Ferini-Strambi L. The risk of neurodegeneration in REM sleep behavior disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Sleep Med Rev 2019; 43: 37-46.

23. Hogl B, Stefani A, Videnovic A. Idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder and neurodegeneration - an update. Nat Rev Neurol 2018; 14: 40-55.

24. Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Tuineaig M, et al. Antidepressants and REM sleep behavior disorder: isolated side effect or neurodegenerative signal? Sleep 2013; 36: 1579-1585.

25. Husain AM, Miller PP, Carwile ST. REM sleep behavior disorder: potential relationship to post-traumatic stress disorder. J Clin Neurophysiol 2001; 18: 148-157.

26. Elliott JE, Opel RA, Pleshakov D, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder increases the odds of REM sleep behavior disorder and other parasomnias in Veterans with and without comorbid traumatic brain injury. Sleep 2020; 43: zsz237.

27. Barone DA. Dream enactment behavior-a real nightmare: a review of post-traumatic stress disorder, REM sleep behavior disorder, and trauma-associated sleep disorder. J Clin Sleep Med 2020; 16: 1943-1948.

28. Heidbreder A, Philipp K. Anti-IgLON 5 disease. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2018; 20: 29.

29. Gan-Or Z, Mirelman A, Postuma RB, et al. GBA mutations are associated with rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2015; 2: 941-945.

30. Akyildiz UO, Tezer FI, Koc G, et al. The REM-sleep-related characteristics of narcolepsy: a nation-wide multicenter study in Turkey, the REMCON study. Sleep Med 2022; 94: 17-25.

31. Howell M, Avidan AY, Foldvary-Schaefer N, et al. Management of REM sleep behavior disorder: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med 2023; 19: 759-768.

32. Howell M, Avidan AY, Foldvary-Schaefer N, et al. Management of REM sleep behavior disorder: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine systematic review, meta-analysis, and GRADE assessment. J Clin Sleep Med 2023; 19: 769-810.

33. Schenck CH, Bundlie SR, Ettinger MG, Mahowald MW. Chronic behavioral disorders of human REM sleep: a new category of parasomnia. Sleep 1986; 9: 293-308.

34. Tuft C, Matar E, Menczel Schrire Z, Grunstein RR, Yee BJ, Hoyos CM. Current insights into the risks of using melatonin as a treatment for sleep disorders in older adults. Clin Interv Aging 2023; 18: 49-59.

35. Gilat M, Coeytaux Jackson A, Marshall NS, et al. Melatonin for rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. Mov Disord 2020; 35: 344-349.