Prescribing menopausal hormone therapy: a practical and evidence-based approach to treatment

Three-quarters of women experience menopausal symptoms, predominantly vasomotor symptoms, with more than a quarter finding these to be moderately to severely bothersome. Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is the most effective treatment for these and other direct consequences of menopause, such as bone loss. Easy access to safe and effective MHT is imperative for improving quality of life and long-term health outcomes for women in midlife.

- The primary indications for menopausal hormone therapy are menopause-specific symptoms, such as vasomotor symptoms and menopause-associated sleep disturbance, and the prevention of bone loss and fragility fractures.

- Care of perimenopausal women includes management of irregular and heavy bleeding and provision of contraception, in addition to symptom relief.

- Although nonoral oestrogen is widely considered to be the preferred option, oral oestrogen is a safe and effective option for most women who do not absorb or cannot tolerate transdermal oestrogen formulations.

- Micronised progesterone and dydrogesterone may be better tolerated than other progestogens, but studies are needed to determine the breast safety of these progestogens beyond three to five years of use with concurrent oestrogen therapy.

- Treatment duration is determined by the persistence of symptoms and competing risk factors, rather than a prespecified age cut-off.

Menopause is the end of a woman’s reproductive lifespan, marked by the final menstrual period following loss of ovarian follicular growth and cessation of oestrogen production. Perimenopause is a transition period of hormonal variation and cycle irregularity that precedes menopause and ends 12 months after the last menstrual period. After 12 consecutive months with no periods, a woman is considered to be postmenopausal.1 The average age of menopause in Australia is 50 to 51 years, with most women reaching menopause between the ages of 45 and 55 years. Menopause occurring between the ages of 40 and 45 years is considered early menopause.

About 75% of Australian women will have vasomotor symptoms (VMS) associated with oestrogen insufficiency, including hot flushes and night sweats, and these are moderately to severely bothersome for about 28% of women.2 Other symptoms of oestrogen insufficiency include low mood, anxiety, sleep disturbance, arthralgia and genitourinary symptoms.3 Many women also report ‘brain fog’ during perimenopause, which tends to lessen in the postmenopausal period.4 Increased abdominal fat accumulation is associated with adverse metabolic changes, and loss of bone mass and deterioration in bone microarchitecture occur even in asymptomatic women.1

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), namely oestrogen, progestogen (progesterone or synthetic progestins) and tibolone, is proven to be the most effective treatment for menopausal VMS.3 Postmenopausal testosterone therapy should be restricted to women with a decline in libido that is of concern to them.5 As this is not an essential component of MHT, testosterone therapy will not be discussed further in this article.

Traditional nonhormonal menopausal treatment options for VMS include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and gabapentin, which have some evidence of benefit, although they are less effective than MHT.6 A newer neurokinin 3 receptor antagonist, fezolinetant, targets the brain’s neuronal thermoregulatory control, with significant reductions in VMS.7 Over-the-counter complementary therapies have no proven benefit for treating VMS.8 A review of these therapies is also beyond the scope of this article.

Premature ovarian insufficiency is defined as cessation of ovarian function before the age of 40 years. The specialised management of this condition is outside the scope of this article but is covered in detail in the recent European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology guidelines.9

Indications for MHT

VMS, menopause-associated sleep disturbance, emotional lability, anxiety and arthralgia remain the primary indications for MHT.10-13 Genitourinary symptoms of menopause (vaginal dryness; urinary frequency, urgency and infections; and dyspareunia) can be effectively treated with local vaginal oestrogen, either alone or in combination with systemic MHT.14

MHT also prevents bone loss and reduces fracture risk in postmenopausal women, irrespective of their baseline bone density.15,16 Oestrogen therapy is TGA approved for preventing osteoporosis in postmenopausal women at high risk of fracture who are intolerant of other approved osteoporosis therapies, or for whom these are contraindicated.17,18

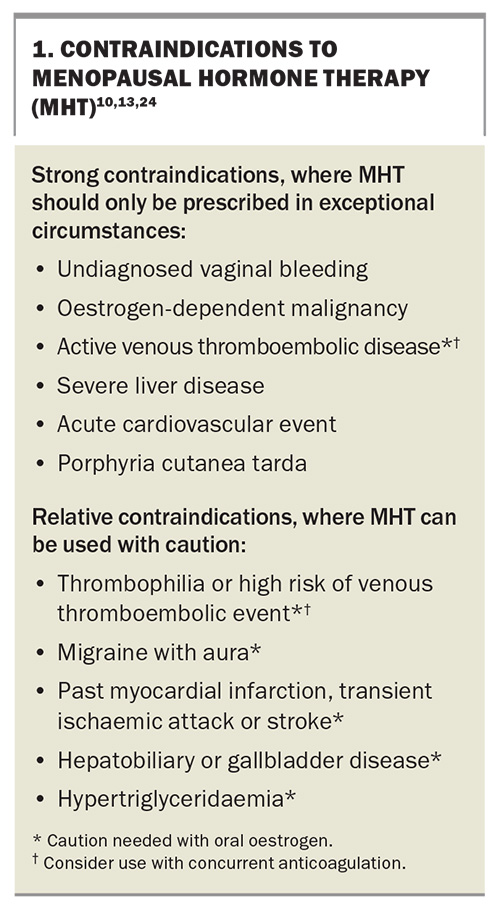

Although oral oestrogen-only therapy was associated with a reduction in myocardial infarctions in the 13-year follow up of the Women’s Health Initiative trials, in women aged 50 to 59 years at initial screening, MHT should not be initiated with the sole aim of preventing heart disease.19 Conditions that are considered contraindications to MHT are shown in Box 1.20

When initiating MHT, measurement of hormone levels is not required for women aged 45 years or older who have experienced changed menstrual patterns and menopausal symptoms. Measurement of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and oestradiol levels may be diagnostically helpful for women who have symptoms other than VMS and who are unable to rely on amenorrhoea as a sign of menopause because of a hysterectomy, endometrial ablation, hormonal intrauterine device or hypothalamic amenorrhoea.3

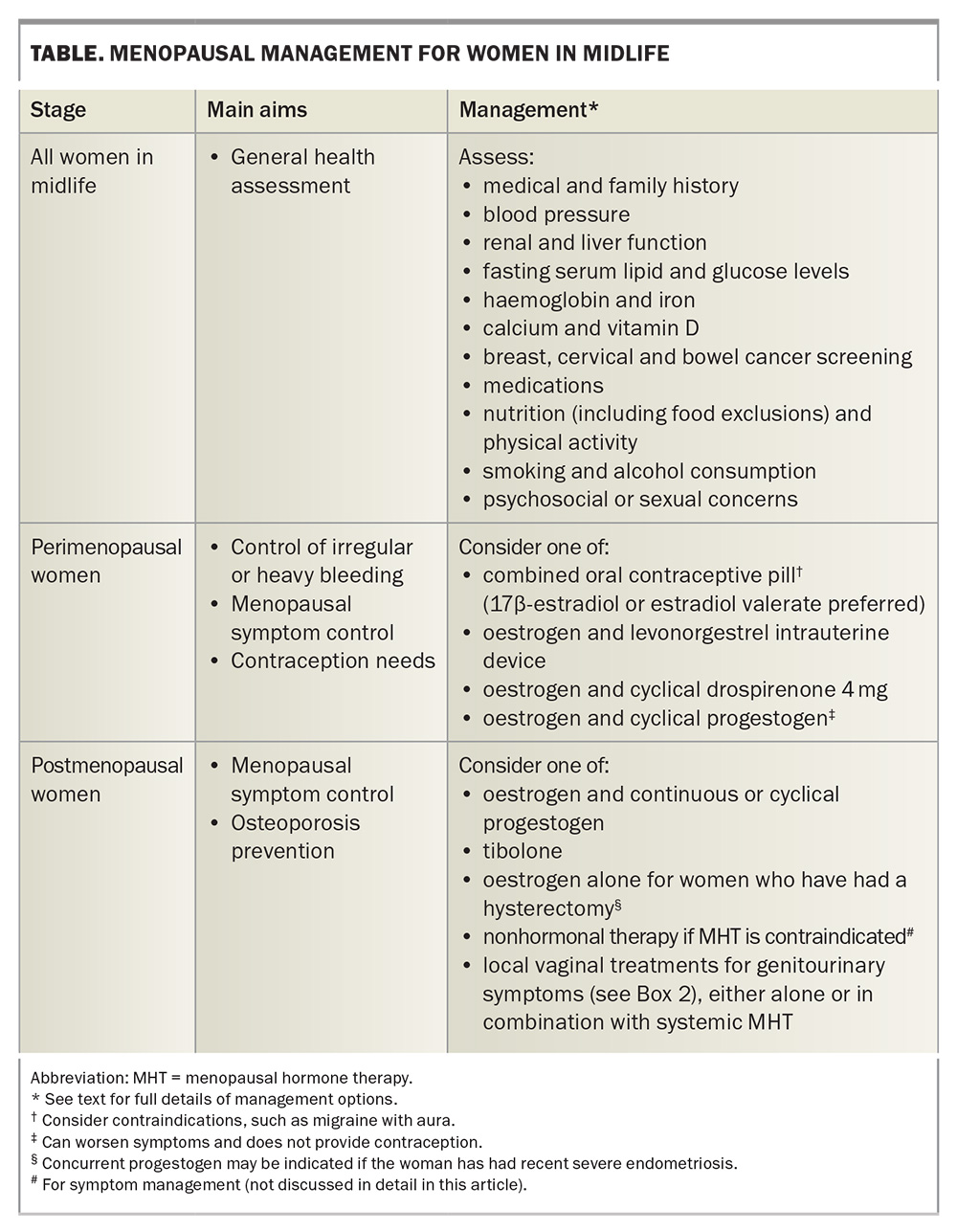

General health evaluation before starting MHT

The menopause transition is an important gateway through midlife for women, which provides an excellent opportunity to undertake general health screening and primary prevention strategies. A woman’s metabolic health can be evaluated at this time, including blood pressure, renal and liver function, fasting serum lipid and glucose levels, and nutrition and physical activity. Haemoglobin and iron studies should be done if there is excessive vaginal bleeding. Recommended bone health strategies include ensuring adequate dietary calcium intake, vitamin D level and multimodal impact exercise. All medication use, including nonprescription products, should be reviewed. Age-appropriate cancer screening, including mammography and screening for cervical and bowel cancer, should be encouraged. It is prudent to offer smoking cessation advice (where relevant) and review alcohol consumption, as well as discussing any psychosocial or sexual concerns a woman may have.12,21

Prescribing MHT

The principles of prescribing MHT can be divided into management of peri-menopausal women and management of postmenopausal women (i.e. those who had their final menstrual period more than 12 months prior). A summary of management is shown in the Table, and useful flowcharts relating to the care of perimenopausal and postmenopausal women are available in A practitioner’s toolkit for managing menopause (www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/3476072/a-practitioners-toolkit-for-managing-menopause.pdf).21 Irrespective of menopause stage, custom compounded hormone therapy should be avoided, as compounded hormone formulations have not been tested for dose, efficacy or safety and do not have regulatory oversight.

All women with an intact uterus who are prescribed oestrogen require concurrent progestogen therapy, as there is an increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia with unopposed oestrogen. Women who have undergone a hysterectomy require oestrogen therapy alone, unless they have had recent severe endometriosis, in which case a progestogen may be indicated. Tibolone is an approved MHT-like formulation that has intrinsic oestrogen and progestogen actions and is therefore prescribed as a single hormone therapy.10-13

Management of perimenopausal women

During perimenopause, the ovaries function erratically, resulting in unpredictable fluctuating hormone levels, intermittent ovulation, and unscheduled and often heavy bleeding. Some women experience worsening premenstrual symptoms during this time. Superimposing cyclical MHT (continuous oestrogen with cyclical progestogen) on erratic ovarian function can make symptoms worse. Consideration therefore needs to be given to control of irregular or heavy bleeding, fluctuating symptoms in the context of inconsistent cycles and hormone release, and contraception.

Management options for perimenopausal women include use of either a combined oral contraceptive pill or a progestin-only pill. A combined oral contraceptive pill containing 17β-estradiol or estradiol valerate is preferred for symptom control, although low-dose ethinyloestradiol can be used. The usual contraindications to the combined oral contraceptive pill, such as migraine with aura, should be considered with any formulation. The progestin-only pill containing drospirenone 4 mg will inhibit ovarian function, and therefore relieve cyclical symptoms, and can be used with supplementary oestrogen for perimenopausal women who are also experiencing VMS.

A levonorgestrel intrauterine device will provide contraception and reduce bleeding. It can be used with concurrent oestrogen to alleviate oestrogen insufficiency symptoms, but it will not reduce cyclical symptoms related to underlying ongoing fluctuations in ovarian function.21

Management of postmenopausal women

Women’s responses to MHT will vary according to their absorption, metabolism and tissue sensitivity to oestrogen or progestogen therapy. There is no target level of oestradiol in the blood that predicts MHT efficacy. In part, this is because of the vast variation in effective oestradiol levels between individuals. Additionally, more than 50% of oestrogen in the blood of postmenopausal women circulates as oestrone or oestrone sulphate, which are not detected with a serum oestradiol test. Hence, treatment efficacy should be based on symptom control rather than by monitoring oestradiol and FSH levels in the blood.22

To limit the potential for side effects, including breakthrough bleeding, MHT should be started with a low oestrogen dose and titrated upwards as needed every six to 12 weeks, based on reduction in symptoms.23 The available forms of oestrogen and progestogen therapies, and their doses, are detailed in A practitioner’s toolkit for managing menopause.21

Oestrogen is the primary component of MHT that provides symptom relief. A progestogen is prescribed in combination with oestrogen for women with an intact uterus, to provide endometrial protection.24,25 Progestogens are ideally prescribed continuously to avoid vaginal bleeding. However, it may be helpful to initiate cyclical progestogen therapy to induce a scheduled bleed for the first three to six months and reduce the likelihood of breakthrough bleeding.

Although there is a big push for women to use transdermal oestrogen therapy, most women can effectively and safely use MHT with low- to standard-dose oral oestrogen–progestogen therapy, unless contraindicated by a history of venous thromboembolic disease, migraine with aura, or malabsorption.26 Furthermore, not all women absorb transdermal oestradiol from a patch or gel effectively, or the product may cause skin irritation.

Some ‘experts’ advocate prescribing two to three times the highest doses of oestrogen patches or gels to overcome poor absorption. However, not only is there no evidence to support this approach, such overprescribing might expose women to high endometrial levels of oestrogen with inadequate progestogen protection. The safety of simply upping the progestogen dose to theoretically counteract the effects of high-dose oestrogen on the endometrium is completely unknown, especially with regard to breast cancer risk. High-dose transdermal oestradiol should not be considered risk-free, with one large observational study showing a small but statistically significantly increased risk of stroke.27

All progestogens exert protective effects on the endometrium; however, they differ in potency and interactions with other steroid receptors. For example, drospirenone has an antimineralocorticoid effect and may lower blood pressure and be less likely to cause fluid retention, whereas norethisterone has potential androgenic effects. Some women require a synthetic progestogen to achieve adequate endometrial protection.24

Tibolone is a synthetic steroid metabolised in the gut, liver and peripheral tissues to produce isomers that exert oestrogenic, progestogenic and androgenic effects. It effectively alleviates VMS and improves mood. Tibolone should only be started in the postmenopausal period to reduce the potential for unscheduled bleeding, although it can be prescribed for symptom relief in perimenopausal women who have had a hysterectomy. It is prescribed as a single agent and is not added to other MHT preparations.12

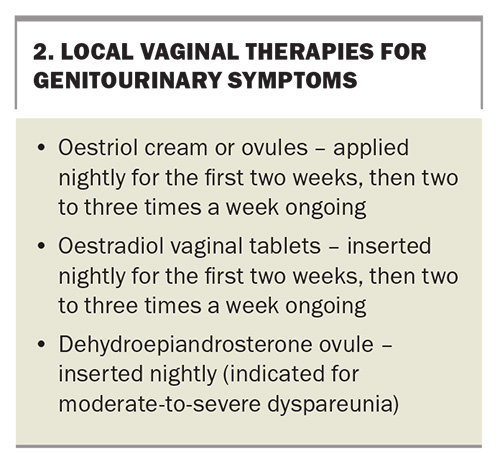

Genitourinary symptoms can be managed with local vaginal treatments (Box 2). These can be used either as monotherapy for women with isolated genitourinary symptoms or in addition to systemic MHT. As systemic absorption of vaginal oestrogen is minimal, it can be used in women with a history of breast cancer, and a concurrent progestogen is not required. However, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone is not approved for use in women with a history of breast cancer. Other causes of genital symptoms, including dermatitis, lichen sclerosis, lichen planus and sexually transmitted diseases, should be excluded.14 Pelvic floor muscle training with a specialised physiotherapist can also be considered in a multimodal treatment approach.28

Risks of MHT

Combined oestrogen and progestogen therapy has been associated with an increase in breast density and a small but statistically significantly increased risk of breast cancer. A nested case-control study in the United Kingdom, involving more than 98,000 women diagnosed with breast cancer between 1998 and 2018 and more than 450,000 controls, found that less than five years of MHT use from the age of 50 to 59 years resulted in an additional three cases of breast cancer per 10,000 women-years with oestrogen-only use, and an additional nine cases per 10,000 women-years with combined oestrogen and progesterone use. The risk was higher in older women, in those with longer (more than five years) MHT use, and with use of norethisterone.29 However, to put these results into perspective, the additional breast cancer risk attributable to MHT use is similar to that associated with a sedentary lifestyle, obesity or excess alcohol consumption.10,13

No increase in breast cancer risk was observed with oral conjugated oestrogen use alone in the Women’s Health Initiative study.30 It is not known if this finding is specific to conjugated oestrogen, or whether it can be generalised to all oestrogen-only therapy. As such, caution should be used in considering all oestrogen-only therapy as being free of breast cancer risk.

Both micronised progesterone and dydrogesterone, a retroisomer of progesterone, are often said to be neutral in terms of breast cancer risk.24,25 However, observational data do not confirm that there is no increased risk of breast cancer with more than five years of use of these progestogens.31 Randomised clinical trial data beyond 12 months of use are lacking.

Oral oestrogen acts as a prothrombotic agent and therefore increases the risk of developing a venous thromboembolism (VTE). The same is not seen with transdermal oestradiol. Nor was this risk seen with use of oral oestradiol 1 mg per day when combined with dydrogesterone in a large observational study.26 The risk of VTE with use of oral oestrogen is further exacerbated by obesity, smoking, increasing age, prior history of VTE or known thrombophilia.12 Haematology review and concurrent prophylactic anticoagulation therapy may be needed for a woman with a known thrombophilia or prior VTE, if MHT is considered necessary for symptom control and quality of life in the setting of inadequate response to nonhormonal therapies.

Tibolone is not prothrombotic and does not increase breast density. When used at a dose of 1.25 mg/day (or half of the available 2.5 mg tablet daily), it improves bone density and reduces fracture risk in women with osteoporosis. In a clinical trial of more than 4500 women, tibolone was associated with a 68% lower risk of breast cancer, but a small increase in the risk of ischaemic stroke (1% vs 0.5% in the placebo group), in women with a mean age of 68 years.32

Potential contraindications to MHT use are summarised in Box 1. This list is divided into strong contraindications, where MHT should generally not be prescribed except for exceptional or rare circumstances, and relative contraindications, where the balance of benefit to risk for individual patients needs to be considered before prescribing.

In 2012, it was proposed that ‘systemic hormone therapy is an acceptable option for relatively young (up to age 59 or within 10 years of menopause) and healthy women who are bothered by moderate-to-severe menopausal symptoms’.33 However, this was not stating that MHT should not be initiated outside of these limits. A recent review of the prescribing of MHT to symptomatic women 10 years past menopause or over the age of 59 years concluded that, ‘Rather than this strong chronological focus, individual risk factors should be the primary consideration when discussing the benefits and risks of initiating MHT with each woman’.34

Duration of MHT

There is no mandatory age for cessation of MHT. Shared decision-making between each patient and her treating clinician, during six- to 12-monthly reviews, should be based on the ongoing need for VMS control and the development of any new risk factors or contraindications. If possible, dose reduction should be considered with increasing age, as well as a switch to transdermal oestradiol, if not done previously, to reduce VTE risk. If the decision is made to cease MHT, there is no clear benefit to either gradual weaning or immediate cessation. However, given the prevalence of persistent VMS in more than 40% of women aged 60 to 65 years, women need to be aware that symptoms may return, possibly requiring reintroduction of treatment.2 Therefore, a gradual reduction in oestradiol dose, which may take months or years, may be better tolerated. Low-dose vaginal oestrogen can be used at any age and continued long term for women with persistent genitourinary symptoms.2,10,11,13,24

Conclusion

Access to MHT is essential to optimise women’s health and wellbeing during perimenopause and beyond. Prescription of either an oestrogen and progestogen, or of tibolone, can provide the most benefit for symptom management, with a low absolute risk of potential harm. Individualised risks and benefits need to be discussed in a shared treatment model between patient and clinician, so as to agree on the most appropriate treatment regimen and achieve the best outcome for each woman. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Szwarcbard: None. Professor Davis has prepared and delivered educational presentations for Besins Healthcare, Abbott Laboratories, Bayer and Mayne Pharma; has served on Advisory Boards for Theramex, Astellas, Abbott Laboratories, Mayne Pharma and Besins Healthcare; and has received institutional research grant funding from Ovoca Bio and Lawley Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. What is menopause? Melbourne: Australasian Menopause Society; 2022. Available online at: https://www.menopause.org.au/hp/information-sheets/what-is-menopause (accessed February 2025).

2. Gartoulla P, Worsley R, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Moderate to severe vasomotor and sexual symptoms remain problematic for women aged 60 to 65 years. Menopause 2015; 22: 694-701.

3. Hemachandra C, Taylor S, Islam RM, Fooladi E, Davis SR. A systematic review and critical appraisal of menopause guidelines. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2024; 50: 122-138.

4. Maki PM, Jaff NG. Brain fog in menopause: a health-care professional’s guide for decision-making and counseling on cognition. Climacteric 2022; 25: 570-578.

5. Parish SJ, Simon JA, Davis SR, et al. International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health clinical practice guideline for the use of systemic testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Climacteric 2021; 24: 533-550.

6. Non-hormonal treatments for menopausal symptoms. Melbourne: Australasian Menopause Society; 2024. Available online at: https://www.menopause.org.au/hp/information-sheets/nonhormonal-treatments-for-menopausal-symptoms (accessed February 2025).

7. Chavez MP, Pasqualotto E, Ferreira ROM, et al. Fezolinetant for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: a meta-analysis. Climacteric 2024; 27: 245-254.

8. Complementary and herbal medicines for hot flushes. Melbourne: Australasian Menopause Society; 2018. Available online at: https://www.menopause.org.au/hp/information-sheets/complementary-and-herbal-therapies-for-hot-flushes (accessed February 2025).

9. Panay N, Anderson RA, Bennie A, et al. Evidence-based guideline: premature ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod Open 2024; 2024: hoae065.

10. de Villiers TJ, Hall JE, Pinkerton JV, et al. Revised global consensus statement on menopausal hormone therapy. Climacteric 2016; 19: 313-315.

11. Lambrinoudaki I, Armeni E, Goulis D, et al. Menopause, wellbeing and health: a care pathway from the European Menopause and Andropause Society. Maturitas 2022; 163: 1-14.

12. Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100: 3975-4011.

13. Faubion SS, Crandall CJ, Davis L, et al; The North American Menopause Society 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2022; 29: 767-794.

14. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Melbourne: Australasian Menopause Society; 2024. Available online at: https://www.menopause.org.au/hp/information-sheets/genitourinary-syndrome-of-menopause (accessed February 2025).

15. Torgerson DJ, Bell-Syer SE. Hormone replacement therapy and prevention of nonvertebral fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA 2001; 285: 2891-2897.

16. Cauley JA, Robbins J, Chen Z, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA 2003; 290: 1729-1738.

17. Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019; 104: 1595-1622.

18. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), Healthy Bones Australia. Osteoporosis management and fracture prevention in postmenopausal women and men over 50 years of age, 3rd edition. Melbourne: RACGP; 2024. Available online at: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/osteoporosis (accessed February 2025).

19. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA 2013; 310: 1353-1368.

20. Hodis HN, Mack WJ. Menopausal hormone replacement therapy and reduction of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: it is about time and timing. Cancer J 2022; 28: 208-223.

21. Davis SR, Taylor S, Hemachandra C, et al. The 2023 Practitioner’s Toolkit for Managing Menopause. Climacteric 2023; 26: 517-536.

22. Kuhl H. Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration. Climacteric 2005; 8 Suppl 1: 3-63.

23. Stevenson JC, Durand G, Kahler E, Pertynski T. Oral ultra-low dose continuous combined hormone replacement therapy with 0.5 mg 17beta-oestradiol and 2.5 mg dydrogesterone for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms: results from a double-blind, controlled study. Maturitas 2010; 67: 227-232.

24. Davis SR, Baber RJ. Treating menopause - MHT and beyond. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022; 18: 490-502.

25. Davis SR. Micronised progesterone as a component of menopausal hormone therapy. Medicine Today 2017; 18(1): 53-55.

26. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ 2019; 364: k4810.

27. Renoux C, Dell’aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: a nested case-control study. BMJ 2010; 340: c2519.

28. Mercier J, Dumoulin C, Carrier-Noreau G. Pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: why, how and when? Climacteric 2023; 26: 302-308.

29. Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ 2020; 371: m3873.

30. Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 476-486.

31. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet 2019; 394: 1159-1168.

32. Cummings SR, Ettinger B, Delmas PD, et al. The effects of tibolone in older postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 697-708.

33. Stuenkel CA, Gass ML, Manson JE, et al. A decade after the Women’s Health Initiative—the experts do agree. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: 2617-2618.

34. Taylor S, Davis SR. Is it time to revisit the recommendations for initiation of menopausal hormone therapy? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2025; 13: 69-74.