Menopausal hormone therapy and cardiovascular risk

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is indicated for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the prevention of osteoporosis in menopausal women. The risks associated with MHT use are influenced by the time since the final menstrual period and by pre-existing cardiovascular disease (CVD). However, many women with CVD risk factors are also potential candidates for MHT for alleviation of VMS symptoms. This article reviews when, how and for whom MHT is appropriate.

- Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is indicated for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and the prevention of osteoporosis in menopausal women.

- MHT is not currently recommended for the primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).

- For women who are at increased risk of CVD, it is essential to implement appropriate lifestyle measures and treat cardiovascular risk factors before considering MHT for the treatment of moderate to severe VMS.

- The Australian CVD Risk Calculator should be used in specified age groups

to categorise pre-existing CVD risk. - For women with a low CVD risk (less than 5%), following individual risk-benefit assessment, oral

or transdermal MHT may be used. - For women with a medium CVD risk (between 5 and less than 10%), following individual risk-benefit assessment, transdermal rather than oral MHT is recommended.

- For women with a high CVD risk (greater than or equal to 10%), MHT is not generally recommended. However, when symptoms are severe, following appropriate treatment of cardiovascular risk factors and specialist review, transdermal MHT may be commenced.

Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) is the most effective treatment for the relief of menopausal vasomotor symptoms (VMS) and is indicated for the relief of VMS and the prevention of osteoporosis in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women who are at high risk of future fracture.1 However, some women cannot use MHT because of contraindications or perceived contraindications, and other women simply prefer not to use hormonal therapies. In particular, the use of MHT in women with significant cardiovascular disease (CVD) is still debated. This article discusses the CVD risk associated with MHT.

Indications and contraindications for MHT

MHT is primarily indicated for symptom relief in the management of bothersome VMS and the prevention of osteoporosis in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. MHT is also indicated for the treatment of women with premature ovarian insufficiency, even in the absence of bothersome VMS, until at least the natural age of menopause.1 This recommendation is because of the recognition that women with premature ovarian insufficiency are at increased risk of premature morbidity and mortality.1

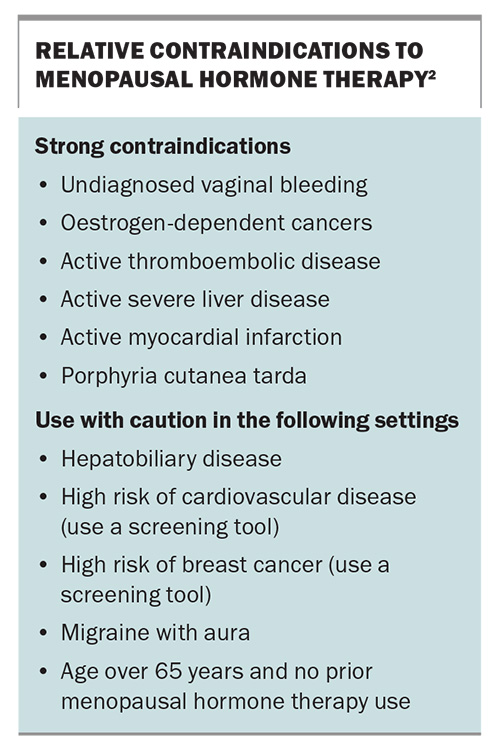

There are a range of contraindications for MHT (Box).2 These include strong contraindications and contraindications to use caution with.

Vasomotor symptoms

VMS are experienced by 60 to 80% of women during the menopause transition. VMS are classified as mild (a sensation of heat with minimal bother), moderate (a sensation of heat accompanied by sweating with some bother) and severe (a sensation of heat and sweating that is distressing and interrupts daily activities or sleep). About 25% of women in Australia experience moderate to severe VMS.3 VMS persist on average for 7.4 years; however, moderate to severe symptoms are reported in 6.5% of women in their sixties.3 VMS are associated with endothelial dysfunction and increased cardiovascular risk, and their duration is influenced by ethnicity, age at onset, obesity, smoking and educational status, factors which are also linked to CVD risk.4

Does MHT affect cardiovascular disease risk?

CVD is a primary cause of morbidity and mortality in postmenopausal women. CVD risk reduction is therefore central to the care of women who are in this stage of life. Such measures traditionally include smoking cessation, a healthy lifestyle and weight loss (when appropriate), as well as management of blood pressure, diabetes and lipids.1,2

Despite the cardiovascular benefits of ovarian oestrogens in reproductive life, similar CVD benefits arising from the use of MHT have been harder to prove, except for in women who experience premature ovarian insufficiency.5 When commenced within 10 years of the final menstrual period (FMP), MHT has been shown to exert favourable effects on serum lipids, insulin sensitivity, body composition, arterial stiffness and chronic inflammation, resulting in an improved CVD risk profile. These benefits may not be seen when MHT is initiated in older women or women with existing CVD.6

The first randomised trial of MHT compared with placebo for the secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) in postmenopausal women with established coronary atherosclerosis (the HERS II trial) found no overall cardiovascular benefit and an initial increase in adverse IHD events with oral MHT use that diminished over time.7 The publication of results from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) trials in 2002 and 2004 raised further concerns regarding MHT and CVD, with initial results from the combined oestrogen plus progestin (E+P) trial reporting that, compared with placebo, the risk of IHD, stroke and venous thromboembolism was increased with MHT.8,9 These two major randomised placebo-controlled trials of oral MHT both concluded that there was no role for MHT in primary or secondary protection against CVD.

Subsequent age-stratified analysis of WHI data, with follow-up of a median duration of 13 years, found that the absolute risk of adverse events following MHT initiation was lower for women aged 50 to 59 years than for older women.10 The proposition that early initiation of MHT has beneficial effects on cardiovascular health was supported by data from the Nurses’ Health Study, which demonstrated a benefit when starting MHT less than four years after the FMP compared with starting MHT more than 10 years after the FMP.11,12

The Danish Osteoporosis Prevention Study similarly found that women receiving MHT for 10 years, plus 5.7 years of post-intervention follow up, had a reduced risk of composite cardiovascular safety outcomes, death or hospitalisation for myocardial infarction (MI) or heart failure.13 A Cochrane systematic review also argued against a role for MHT in the primary prevention of CVD but, in a subgroup analysis, found that women who initiated MHT within 10 years of their FMP had lower all-cause mortality and fewer cardiac events.14

MHT is known to have mostly favourable effects on serum lipids. The Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE) compared healthy menopausal women using oral estradiol and vaginal progesterone or placebo. This study found that when MHT was initiated within six years of the FMP, compared with greater than 10 years from the FMP, there was attenuation of progression of subclinical atherosclerosis, as measured by carotid intima media thickness.15

Overall, these studies support the hypothesis that cardiovascular risk associated with hormone therapy depends on the timing of initiation of MHT after the FMP. The route of delivery also affects cardiovascular risk to some extent; oral estrogens are known to increase thromboembolic risk, but transdermal delivery of estradiol does not increase that risk above baseline. For most women, MHT provides a highly effective low-risk option for the treatment of menopausal symptoms when initiated in those under the age of 60 years or within 10 years of the FMP; however, risk varies as underlying cardiovascular risk increases.16,17

Stratifying cardiovascular risk

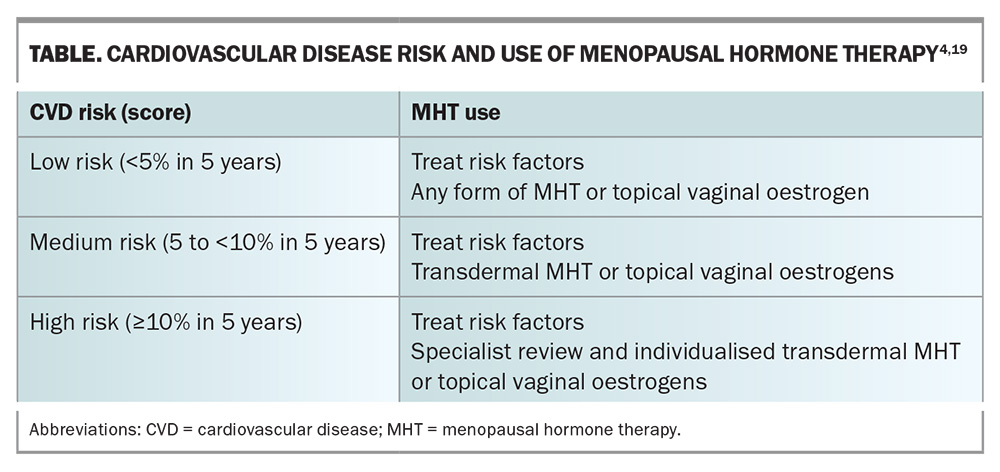

The Australian CVD Risk Calculator (available at www.cvdcheck.org.au) produces a CVD risk estimate expressed as a percentage probability of dying or being hospitalised because of a heart attack, stroke or vascular disease in the next five years.18 The Australian Heart Foundation recommends using this risk calculator for all people between ages 45 and 79 years, for people with diabetes between ages 35 and 79 years, and for First Nations people between ages 30 and 79 years. Cardiovascular risk categories are divided into low, medium and high, and decisions on the use of MHT will differ with each category of CVD risk (Table).4,19

Women also have several sex-specific risk factors for CVD. These include early age at menarche, premature ovarian insufficiency or early menopause, polycystic ovarian syndrome, migraine, autoimmune disease, parity, adverse pregnancy outcomes, recurrent miscarriage, infertility, depression and anxiety. CVD in women may present differently to CVD in men and diagnosis is often delayed.

When an increased risk of CVD is suspected, the level of risk may be further refined by coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring. CAC is a marker of atherosclerotic disease burden and is highly prognostic of atherosclerotic CVD risk, independent of traditional risk factors. Although at any given age women are less likely to have prevalent CAC than men, when it is present, CAC is associated with a greater relative risk of CVD in women compared with men. It may be prudent for a cardiology assessment to be performed in patients with CAC and for transdermal MHT, rather than oral, to be used, when necessary.19

Recommendations for MHT use in women with cardiovascular disease risk factors

Low-risk women

Women aged under 65 years or within 10 years of their FMP with a CVD risk score of less than 5% and without other contraindications may be prescribed MHT for the alleviation of bothersome menopausal VMS. Either the oral or transdermal route of delivery may be chosen, based on the patient’s preference after discussion of individual risks and benefits (Table).4,19,20 Continuation of therapy should be reviewed annually or if new clinical concerns arise. There is no mandatory cessation time for MHT use.

Medium-risk women

For women aged under 65 years or within 10 years of their FMP with a CVD risk score of between 5 and less than 10%, MHT may be appropriate to alleviate bothersome VMS. It is important that underlying CVD risks such as obesity, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and diabetes are addressed before commencing MHT. In most cases, because of the reduced thromboembolic risk, transdermal delivery of body-identical estradiol is suggested (in combination with micronised progesterone for women with an intact uterus).20 There is no mandatory age for cessation of MHT. Rather, the decision to continue MHT should be reviewed annually, or if new clinical concerns arise. Shared decision making is important in this context in assessing the risk vs benefit of ongoing therapy.

High-risk women

In recent years, mortality from CVD in women aged over 65 years has declined. However, mortality rates from CVD are rising in women aged under 65 years, and mortality risk following MI in these women is almost double that seen in similarly aged men.19 MI with nonobstructive coronary atherosclerosis disproportionately affects younger women. The use of MHT in women with a CVD risk score of greater than or equal to 10% is generally not recommended.18 However, when VMS are severe, MHT may be considered for symptom relief following review by a cardiologist or a multidisciplinary specialist menopause service. Treatment should only be commenced in women within 10 years of the FMP or aged under 65 years and only after treatment for concomitant CVD risk factors has been commenced, including lifestyle measures. Body-identical estradiol and progesterone are recommended, and delivery should be transdermal as this has minimal effect on inflammatory markers and minimises any thromboembolic risk. Topical vaginal hormone therapy for treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy is not contraindicated.

Conclusion

MHT is the most effective treatment for VMS in menopausal women and is not recommended for the primary or secondary prevention of CVD. Lifestyle measures should be implemented and CVD risk factors should be treated before considering the use of MHT. The Australian CVD Risk Calculator should be used in specified age ranges to categorise pre-existing CVD risk into low, medium or high risk; the recommended MHT use differs depending on the category. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: Dr Rodrigo: None. Dr Baber has received payment or honoraria for lectures from Astellas, Besins Healthcare and Theramex; has participated on a Medical Advisory Board for Astellas; is a past president of the International Menopause Society and the Australasian Menopause Society; and is a past Editor-in-Chief of Climacteric.

References

1. Baber R, Panay N, Fenton A, et al. IMS recommendations on midlife women’s health and menopause hormone therapy. Climacteric 2016; 19: 109-150.

2. Davis SR, Baber R. Treating menopause – MHT and beyond. Nature Rev Endocrinol 2022; 18: 490-502.

3. Gartoulla P, Worsley R, Bell R, Davis S. Moderate to severe vasomotor and sexual symptoms remain problematic for women aged 60-65 years. Menopause 2015; 25: 1331-1338.

4. Thurston R. Vasomotor symptoms: natural history, physiology and links with cardiovascular health. Climacteric 2018; 21: 96-100.

5. Stevenson J, Collins P, Hamoda H, et al. Cardiometabolic health in premature ovarian insufficiency. Climacteric 2021; 42: 967-984.

6. Nudy M, Chinchilli V, Foy A. A systematic review and meta-regression analysis to examine the ‘timing hypothesis’ of hormone replacement therapy on mortality, coronary heart disease and stroke. J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2019; 22: 123-131.

7. Grady D, Herrington D, Bittner V, et al. Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: heart and estrogen/progestin replacement study follow up (HERS II). JAMA 2002; 288: 49-57.

8. Writing group for the Women’s Health Initiative investigators. Risks and benefits of oestrogen plus progestin in healthy post-menopausal women. JAMA 2002; 288: 321-333.

9. Writing group for the Women’s Health Initiative investigators. Effects of conjugated equine oestrogen in post-menopausal women with hysterectomy. JAMA 2004; 291: 1701-1712.

10. Manson J, Chlebowski R, Stefanick M, et al. MHT and health outcomes during the intervention and extended post stopping phases of the WHI randomised trials. JAMA 2013; 310: 1353-1368.

11. Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and mortality. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 1769-1775.

12. Stampfer M, Colditz G. Estrogen replacement and coronary heart disease: a quantitative assessment of the epidemiological evidence. Prev Med 1991; 20: 47-63.

13. Schierbeck L, Rejnmark L, Landbo L, et al. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular events in recently postmenopausal women: randomised trial. BMJ 2012; 345: e6409.

14. Boardman H, Hartley L, Eisinga A, et al. Hormone therapy for preventing cardiovascular disease in post-menopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015: CD002229.

15. Hodis H, Mack W, Henderson V. Effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 1221-1231.

16. Taylor S, Davis SR. Is it time to revisit the recommendations for initiation of menopausal hormone therapy? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2025; 13: 69-74.

17. Cho L, Kaunitz A, Faubion S, et al. Rethinking MHT: for whom, what, when and how long. Circulation 2023; 14: 597-610.

18. Paige E, Welsh J, Zhang Y, et al. Updating Australia’s cardiovascular disease risk prediction equation: evidence, methods and data for recalibration. National Heart Foundation of Australia; 2022.

19. Rajendran A, Minhas A, Kazzi B, et al. Sex specific differences in cardiovascular risk factors and implications for CVD prevention in women. Atherosclerosis 2023; 384: 117269.

20. Maas AH. Hormone therapy and cardiovascular disease: benefits and harms. Best Practice Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2021; 35: 10156.