Refugee health – the impact of recent global events

Following recent global events, over half of the world’s current refugees are from Syria, Ukraine and Afghanistan. Providing healthcare for the refugee population represents a complex and vast challenge, including consideration of the risk of health conditions acquired in the country of origin and during migration. All refugees arriving in Australia should undergo a comprehensive health assessment.

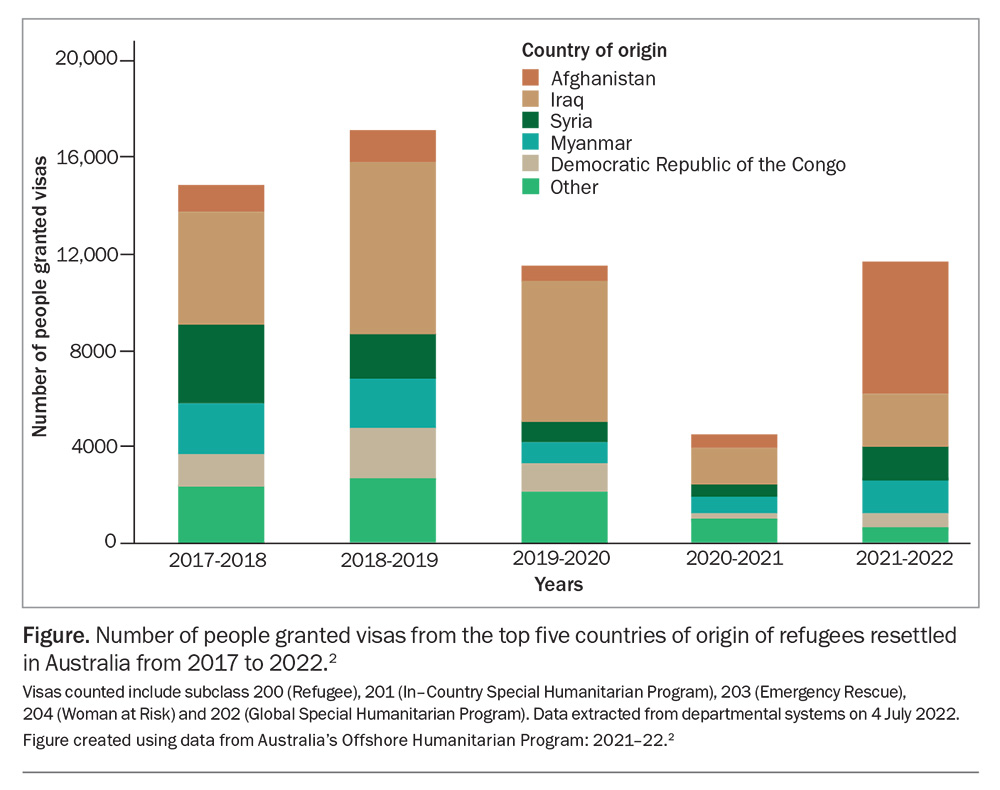

- The top five countries of origin of refugees resettled in Australia from 2017 to 2022 were Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Myanmar and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- Refugees should be given a comprehensive health assessment on arrival in Australia.

- Healthcare providers should consider the risk of infectious and noninfectious diseases that may have been acquired in the country of origin and during migration.

- Over half of the world’s current refugees are from Syria, Ukraine or Afghanistan.

- The COVID-19 pandemic had a devastating impact on refugees, with borders closed and immigration halted or severely restricted.

As of December 2022, 108.4 million people globally were displaced from their homes because of persecution, conflict or catastrophic events. Of these, 35.3 million people crossed international borders and were officially recognised as refugees under the mandates of the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East.1

There were 19 million more newly displaced people in 2022 compared with 2021; this was the largest between-years increase in forcibly displaced people ever recorded by the UNHCR.1 In February 2022, the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine created the fastest displacement crisis since the Second World War. In the first five weeks of the conflict, more than four million refugees from Ukraine crossed borders into neighbouring countries.

At the end of 2022, 11.6 million Ukrainians (25% of Ukraine’s population) remained displaced, including 5.7 million who fled to neighbouring countries and beyond as refugees. In addition, population recounts conducted by the Islamic Republic of Iran revealed that there were 2.9 million previously undocumented displaced Afghans residing in the country, including those who had fled following the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan in 2021. This increased the estimated number of displaced Afghans in Iran to 5.7 million.1

Understanding, planning and providing healthcare to such staggering numbers of diverse people living in a variety of circumstances represents a complex and vast challenge. Refugees have a variety of physical and mental health needs, shaped by experiences in their country of origin, their migration journey, their host country’s entry and integration policies, and living and working conditions. These factors have inter-related effects on the vulnerability of refugees and migrants to chronic and infectious diseases and require a framework of understanding for healthcare to be effective.

The demographics of refugees are constantly changing and healthcare providers should consider the risk of health conditions acquired in the country of origin and during migration. This article discusses Australia’s humanitarian settlement program in recent years, the major countries of origin of refugees resettled in Australia from 2017 to 2022 and the comprehensive health assessment that refugees should undergo on arrival to Australia. It also provides country-specific background information on recent global events that have impacted the health of refugees and require consideration by healthcare providers and policymakers caring for resettled refugees.

Refugees in Australia

Humanitarian settlement program

Australia’s humanitarian settlement program in recent years has largely reflected and responded to global events. Border controls introduced to limit the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) meant that humanitarian visas were suspended in 2020 with only emergency cases granted. Although grant processing formally recommenced in December 2020, ongoing pandemic-induced restrictions in refugee-hosting countries and delays in off-shore processing (e.g. delays in client interviews and medical examinations) caused by local outbreaks of COVID-19 continued to hinder resettlements.

The Taliban takeover in August 2021 resulted in the emergency evacuation and resettlement of Afghan nationals.2 During this period, settlement agencies facilitated the arrival of 5500 refugees to Australia over a two-week period, including the provision of accommodation, health services and documentation without the usual pre-arrival processing, health checks and planning.

Countries of origin

The Figure shows the top five countries of origin of refugees resettled in Australia from 2017 to 2022.2 Most refugees originated from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, comprising 75.4% of new refugee arrivals in 2020 to 2021. Myanmar (14.2%) and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC; 3.9%) were the two other most common countries of origin from 2021 to 2022. Although the proportion of refugees originating from Myanmar remained fairly constant between 2017 and 2022, comprising 11 to 14% almost every year, the proportion of refugees from the DRC and the African region has reduced. From 2017 to 2019, 9.1 to 12.4% of refugees originated from the DRC and 18.0 to 21.9% originated from the African region, whereas from 2020 to 2022, these proportions decreased to 3 to 4% and 7 to 11%, respectively.2

More recently, about 11,500 Ukrainian refugees have arrived in Australia since 2022.3 Overwhelmingly, refugees are young; 62% were aged younger than 30 years in 2021 and 38.4% were children, with an equal sex distribution (50.2% female).2

Implications for healthcare providers

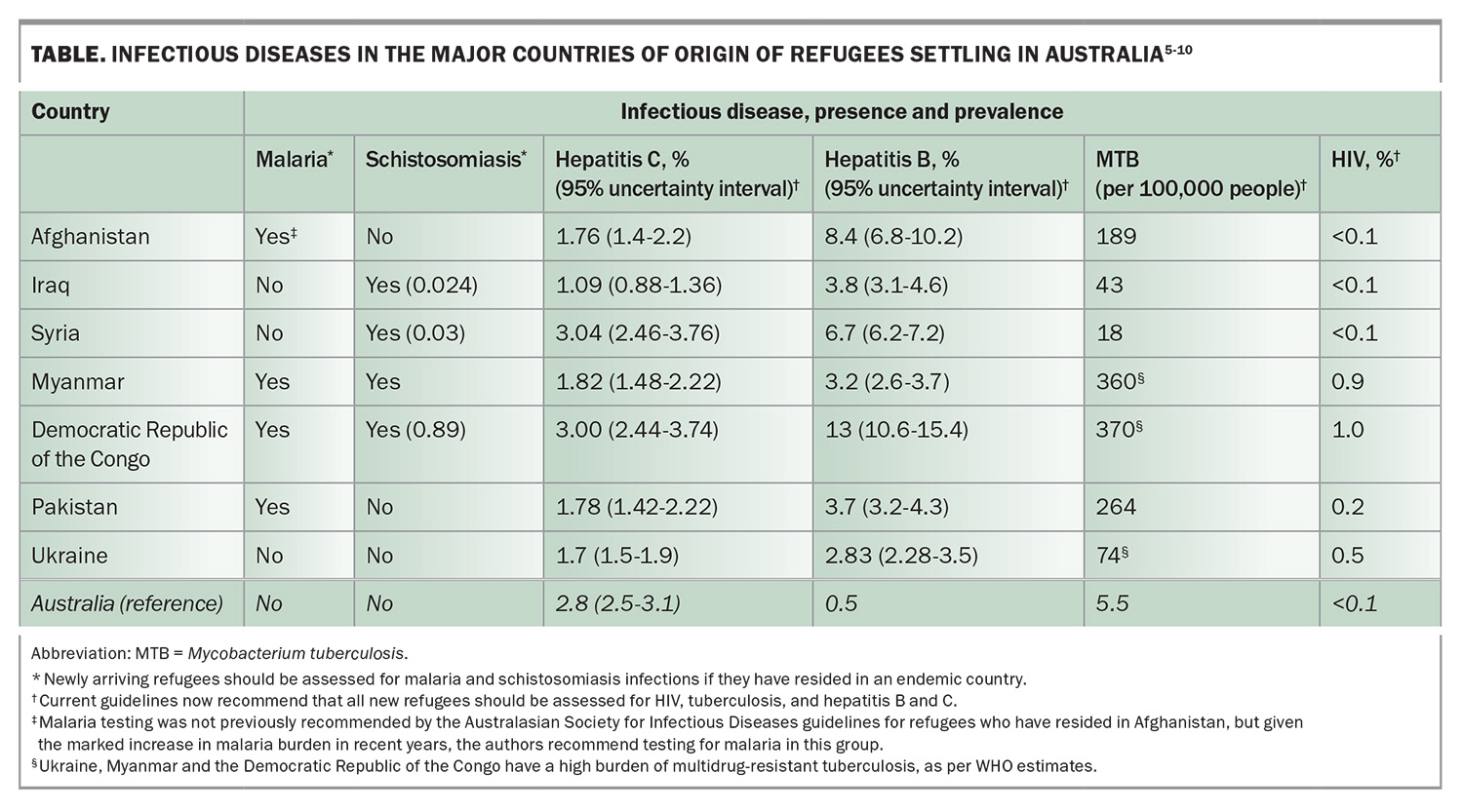

The changing demographics of refugees arriving in Australia has implications for healthcare providers, who need to consider the risk of health conditions (infectious and noninfectious) acquired in countries of origin and during migration. All arriving refugees should undergo a comprehensive health assessment in which the practitioner assesses for infections, nutritional deficiency, chronic disease, growth and development, need for vaccinations, and mental health.4 The assessments are Medicare rebatable, as are translating and interpreting services (https://www.tisnational.gov.au/en/Free-Interpreting-Service). Assessments must be tailored to the individual’s circumstances, including age, sex and region of origin. The Table outlines the estimated prevalence of key infectious diseases in the most common countries of origin of refugees arriving in Australia.5-10

As per the current guidelines, all new refugee arrivals should be assessed for tuberculosis (TB; active and latent infection), hepatitis B and C viruses, and HIV.11 Screening for malaria and schistosomiasis should be conducted if the refugees have resided in countries that are endemic for these infections. It should be noted that many of these conditions are tested as part of predeparture health screening performed overseas; however, healthcare providers should ensure that test results have been reviewed in conjunction with an individual clinical assessment, with further investigation and management conducted as appropriate.11

Noncommunicable diseases are increasingly prevalent among refugee populations.12 The burden of chronic diseases, particularly diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancers, is high in refugee populations both in camp settings and postsettlement, with evidence to suggest that refugee status may increase the risk of these conditions.13 Preventive healthcare strategies, such as early screening and management of hypertension, diabetes, overweight and obesity, raised lipid levels and cancers, are therefore essential.4

Global events and refugee demographics

Over half of the world’s current refugees come from just three countries: Syria, Ukraine and Afghanistan. The majority of the Afghan and Syrian refugees are hosted in camp settings in Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, Jordan and Lebanon. Ukrainian refugees fled to numerous neighbouring countries in Europe (particularly Poland, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, the Republic of Belarus and Germany) and Russia, where they have mainly been housed in private residences.1

Ukraine

Martial law in Ukraine prevented men aged 18 to 60 years from leaving the country after the start of the Ukraine–Russia conflict, so 90% of Ukrainian refugees are women, children and older individuals.14 There were 2030 unaccompanied or separated children recorded by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in March 2020. Protecting this vulnerable cohort from violence, including sexual assault, is a complex but critical task for agencies co-ordinating millions of individuals who are migrating and living in transitory arrangements.15

Ensuring reproductive health has also been an issue. There were an estimated 265,000 pregnant Ukrainians at the outbreak of the war in 2022, many of whom fled the country.16 Healthcare providers have reported high rates of pregnancy complications caused by missed prenatal care, emergency deliveries and maternal stress.17,18

The potential for infectious disease outbreaks among Ukrainian refugees has been high. Many of these individuals have experienced extended periods living in cold, crowded conditions, including poorly ventilated underground shelters, without adequate food and clean water.16

Furthermore, vaccination coverage in Ukraine before the war was insufficient for a number of diseases.19 In February 2022, only 36% of the population had received a complete course of the COVID-19 vaccination. Routine childhood vaccinations are mandated in Ukraine; however, uptake during the 2010s was poor, falling to a low of 43% measles vaccine coverage and 15% polio vaccine coverage in 2015. Outbreaks of measles and polio were the result of these low rates, and the country had undertaken efforts to improve vaccination rates in recent years.

In 2020, 84.9% of children received the measles vaccination, falling short of the 95% vaccination coverage required for herd immunity. Polio vaccination coverage was 81% in 2020; however, in previous years only 56.2% of the eligible population had received a third dose of polio vaccination and about 140,000 children were identified by public health officials in 2019 as being inadequately protected. Similarly, serosurveys found tetanus immunity to be as low as 62% in some regions of Ukraine.19

Vaccination of arriving refugees has been an urgent priority and most reception countries have instituted accessible and free vaccination programs.15,16 Vaccine hesitancy has unfortunately been an issue, with one study finding that 33% and 62% of unvaccinated refugees refused polio and measles, mumps and rubella vaccination, respectively.20

Chronic infectious diseases, such as TB and HIV/AIDS, have also been a concern. Prevalence rates for these conditions in Ukraine are some of the highest in Europe at 0.66% for HIV and 65 per 100,000 for TB.21-23 Moreover, in 2019, 27% of new TB diagnoses in Ukraine were multidrug resistant.23 Ensuring continuity of care is critical to the control of both of these infections; yet access to medicines and healthcare in Ukraine has been increasingly fraught with the breakdown of health infrastructure and over 1000 military attacks on healthcare facilities.24 For example, although newer anti-TB medicines such as bedaquiline and delamanid used in the treatment of multidrug-resistant TB are available in Ukraine, they are not available in many countries, putting individuals at risk of treatment gaps during migration.25 Policies to house refugees in community housing rather than group ‘camp’ settings help to reduce the risk of disease outbreaks, as do schemes to provide free and accessible healthcare for all refugees.15,16

Finally, as with all refugee cohorts, management of noncommunicable diseases, particularly cardiovascular disease and mental health conditions, is critical. Before the war, the age-adjusted death rate for ischaemic heart disease in Ukraine was more than six times higher than that in European Union countries and there was a diabetes prevalence of 7.1%. In 2021, more than a third of refugee households received in Poland had one or more members with a chronic disease for which management had been interrupted.16 Further, over 33% of Ukrainians experience mental illness, with one of the highest suicide rates in the world.14

Afghanistan

Afghanistan has suffered over 23 years of armed conflict, drought and political upheaval. Over 8.2 million Afghans have been forced to flee the country, resulting in one of the largest and most protracted refugee crises in history.

More recently, the sudden withdrawal of allied forces and the Taliban takeover in 2021 resulted in the displacement of over two million Afghans into neighbouring countries. International humanitarian aid was suspended for many months, leading to increasing poverty and food insecurity. Healthcare in Afghanistan is delivered almost entirely by international aid agencies and the effects of suspending these have been far reaching. Emerging public health issues include a five- to 10-fold increase in malaria incidence in the past three years. Afghanistan’s malaria disease burden now ranks fifth highest in the world, after African countries.26,27 Polio remains endemic in Afghanistan and vaccination campaigns have faced escalating security concerns.28

Pakistan hosts over 1.5 million Afghan refugees. In June 2022, devastating floods resulted in a rapid escalation in malaria and dengue cases. There were 3.4 million suspected cases of malaria reported between January and August 2022, compared with 2.6 million suspected cases in 2021 (January to December). Most cases (77%) were caused by Plasmodium vivax. Concurrently, almost 26,000 cases of dengue and 62 deaths (case fatality ratio 0.25%) were reported over the same eight-month period.29,30

Syria

In Syria, 12 years of war, conflict, economic crises and prolonged drought have battered hospitals and health systems (only one-third of Syrian health professionals remain in the country), as well as sanitation and sewage systems.29 The result has been a large and prolonged cholera outbreak with almost 93,000 cases reported between 25 August 2022 and 15 February 2023, including 101 deaths (case fatality rate: 0.11%).31 Cases were first detected in September 2022 and subsequently spread to all 14 governates.29,32 Devastatingly, efforts to contain the outbreak, including deployment of cholera vaccination, were critically impeded when two earthquakes followed by windstorms and floods struck the region in early February. This worsened living conditions further, destroying infrastructure including piping and hospitals, delaying vaccine distribution and further reducing the access of over two million Syrians living in makeshift homes to basic sanitation and clean water.31,33

Shortly after cholera was first reported in Syria, two cases were detected in neighbouring Lebanon, home to over 1.5 million Syrian refugees, in October 2022. A month later, cholera had rapidly spread, with 4337 cases reported from 20 of 26 districts in Lebanon, including 20 associated deaths (case fatality ratio 0.46).29 As of December 2022, there were over 6000 cases of cholera in Lebanon and 100 fatalities.

Recent reports suggest antibiotic resistance to be a potential issue for refugees from both Afghanistan and Syria, with two small studies from Germany and Switzerland reporting very high rates of carriage of extensively drug-resistant organisms in newly arrived Afghan and Syrian refugees.34,35

Gaza, occupied Palestine territory

Gaza has been under Israeli occupation for decades. On 7 October 2023, an assault on Israel by Palestinian armed groups led to Israel launching aerial bombardments and ground operations in Gaza.

Of the 2.3 million people living in Gaza, nearly half (47.3%) are children younger than 18 years of age.36 This very young population has been living under blockade for 16 years with restricted access to water, electricity, food, medical equipment and fuel.36 Access to clean water and sanitation has been a longstanding issue, with UNICEF reporting in 2017 that less than 5% of the water in Gaza was safe for human consumption and only 30% of households were connected to sewage systems.37 Similarly, food insecurity and malnutrition have been longstanding problems: in 2021, more than 60% of Gazans were estimated to be food insecure.

Since October 2023, attacks on water treatment facilities and pipelines, fuel restrictions, power cuts and restrictions on delivering international aid have exacerbated these already critical issues. Over 1.9 million people, more than 70% of the population, are displaced from their homes and living in crowded temporary shelters. It is now estimated that there is one toilet for every 700 people and two to five litres of clean water per person (where 50 to 100 litres per person is required to meet basic needs).38 Over 90% of Gazans were estimated to be suffering food insecurity in 2023.

Military attacks on hospitals and clinics, loss of healthcare providers, power cuts, and lack of medical supplies and equipment has crippled an already fragile healthcare system. Of the 36 hospitals in Gaza, only 17 are still operating and 14 of these are functioning only partially.39 Breakdown of vaccination programs has left the over 300,000 children younger than 5 years of age vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases.40

The combination of displacement, overcrowding, and severely inadequate water, sanitation, food and healthcare have catastrophic implications for the health of Gazans. As of June 2024, the WHO reported 36,731 fatalities and 83,530 injuries, with a further 10,000 people missing. There have been 865,157 reports of acute respiratory infections, 495,315 reports of diarrhoea, 93,690 cases of scabies, 8538 cases of chickenpox and almost 82,000 cases of acute jaundice syndrome (likely acute hepatitis).39

Healthcare providers in settlement countries receiving refugees from Gaza must be alert to the management of these infections, as well as that of malnutrition and, particularly, refeeding syndromes, which have been identified as an issue for Gazan refugees in several settlement countries.

Impact of COVID-19 on refugees

The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted ethnic and racial minorities, with these groups suffering higher rates of both infection and death.41 The impact of COVID-19 on refugee cohorts specifically has been difficult to study and is less understood. For the over 6.5 million people living in crowded refugee camps, implementation of critical measures to limit COVID-19 spread such as social distancing, self-isolation, hand washing and testing seemed impossible.42 Strategies have included subdividing camps, use of face masks, establishing isolation centres, and improving water and sanitation facilities.43 Whether these measures have been effective is largely undocumented.

Two recent studies employed UNHCR health service data to ascertain the incidence rate of COVID-19 in Azraq and Zaatari camps in Jordan (populations of 37,932 and 79,034 people, respectively)44 and in 12 Ugandan refugee settlements (about 1.4 million refugees).45 In both settings, the authors found lower rates of COVID-19 within camps compared with neighbouring communities, which contradicts assumptions that refugee populations would be ‘drivers’ of COVID-19 spread.44,45 The studies were limited, however, by low testing capacity in camps as well as difficulties conducting time series analyses in the volatile setting of camps.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, most countries closed their borders and halted or severely restricted immigration and asylum-seeking services. The impact on refugees was devastating, with settlement delayed by years for those who had already waited extensive periods and camps were further congested. Many refugees and asylum seekers subsist on income generated from tenuous and casual work arrangements. Lockdowns and movement restrictions severely reduced and often eliminated such livelihoods.42 One study of refugees in Brazil described high rates of income loss during the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in worsening poverty and food insecurity, particularly for single income households.46

The toll on the mental health of refugees was highlighted by a WHO survey released in December 2020 of over 30,000 refugees and migrants from different regions in the world. Over half of respondents reported significantly increased depression, fear and anxiety over the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Factors identified as leading to poor mental health included limited access to information, marginalisation and fear of deportation.10

Conclusion

Sadly, recent events remind us how war, conflict, environmental disaster and poverty wreak havoc on the lives of ordinary people. For the over 100 million displaced people and 35 million refugees in the world today, ensuring access to comprehensive and high-quality healthcare will allow them the best chance to face challenges and forge new futures. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. UNHCR. Global trends report 2023. Copenhagen: UNHCR; 2024. Available online at: https://www.unhcr.org/au/media/global-trends-report-2023 (accessed March 2025).

2. Australian Government. Department of Home Affairs. Onshore Humanitarian Programme: 2021-2022. Belconnen: Commonwealth of Australia; 2022. Available online at: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/australia-offshore-humanitarian-program-2021-22.pdf (accessed March 2025).

3. Australian Government. Department of Home Affairs. Ukraine Visa Support. Australian Government; 2024. Available online at: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/help-and-support/ukraine-visa-support (accessed March 2025).

4. Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases and Refugee Health Network of Australia. Recommendations for comprehensive post-arrival health assessment for people from refugee like backgrounds. 2nd edition. Sydney: Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases; 2016. Available online at: https://www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/immigranthealth/ASID-RHeaNA%20screening%20guidelines.pdf (accessed March 2025).

5. World Health Organization. World malaria report 2022. Geneva: WHO; 2022. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2022 (accessed March 2025).

6. Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop 2000; 77: 41-51.

7. World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. Geneva: WHO; 2017. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565455 (accessed March 2025).

8. GBD 2019 Hepatitis B Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of hepatitis B, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022 7: 796-829.

9. World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2022. Geneva: WHO; 2022. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2022 (accessed March 2025).

10. UNAIDS. UNAIDS data 2023. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2023. Available online at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2023/2023_unaids_data (accessed March 2025).

11. Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture Inc (Foundation House). Australian Refugee Health Practice Guide. Brunswick: Foundation House; 2018. Available online at: https://refugeehealthguide.org.au/ (accessed March 2025).

12. World Health Organization. World report on the health of refugees and migrants. Geneva: WHO; 2022. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/health-and-migration-programme/world-report-on-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants (accessed March 2025).

13. Agyemang C, Born BJVD. Non-communicable diseases in migrants: an expert review. J Travel Medicine 2019; 26.

14. Marchese V, Formenti B, Cocco N, et al. Examining the pre-war health burden of Ukraine for prioritisation by European countries receiving Ukrainian refugees. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022; 15: 100369.

15. Kumar BN, James R, Hargreaves S, et al. Meeting the health needs of displaced people fleeing Ukraine: drawing on existing technical guidance and evidence. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022; 7: 100403.

16. Lee ACK, Fu-Meng K, Lindman AES, Juszczyk G. Ukraine refugee crisis: evolving needs and challenges. Public Health 2023; 217: 41-45.

17. Vernikova M. Lots of explosions and shooting outside: giving birth in wartime Ukraine. The New York Times. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/06/02/world/europe/ukraine-war-premature-birth-pregnancy.html (accessed March 2025).

18. Rodríguez-Muñoz MF, Chrzan-Dętkoś M, Uka A, et al. The impact of the war in Ukraine on the perinatal period: perinatal mental health for refugee women (pmh-rw) protocol. Front Psychol 2023; 14: 1152478.

19. Rzymski P, Falfushynska H, Fal A. Vaccination of Ukrainian refugees: need for urgent action. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75: 1103-1108.

20. Troiano G, Torchia G, Nardi A. Vaccine hesitancy among Ukrainian refugees. J Prev Med Hyg 2022; 63: E566-e572.

21. Parczewski M, Jabłonowska E, Wójcik-Cichy K, et al. Clinical perspective on human immunodeficiency virus care of Ukrainian war refugees in Poland. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76: 1708-1715.

22. Massmann R, Groh T, Jilich D, et al. HIV-positive Ukrainian refugees in the Czech Republic. AIDS 2023; 37: 1811-1818.

23. Mencarini J, Spinicci M, Zammarchi L, Bartolini A. Tuberculosis in the European region. Curr Trop Med Rep 2023; 10: 1-6.

24. World Health Organization. WHO records more than 1000 attacks on health care in Ukraine over the past 15 months of full scale war. WHO; 2023. Available online from: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/30-05-2023-who-records-1-000th-attack-on-health-care-in-ukraine-over-the-past-15-months-of-full-scale-war (accessed March 2025).

25. World Health Organization. Delivering quality health services to refugees and migrants from Ukraine. Open WHO; 2022. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-10-2022-new-free-online-course--delivering-quality-health-services-to-refugees-and-migrants-from-ukraine (accessed March 2025).

26. World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2023. Geneva: WHO; 2023. Available online at: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023 (accessed March 2025).

27. Siddiqui JA, Aamar H, Siddiqui A, Essar MY, Khalid MA, Mousavi SH. Malaria in Afghanistan: challenges, efforts and recommendations. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022; 81: 104424.

28. Bhutta ZA. Conflict and polio: winning the polio wars. JAMA 2013; 310: 905-906.

29. Venkatesan P. Disease outbreaks in Pakistan, Lebanon, and Syria. Lancet Microbe 2023; 4: e18-e19.

30. World Health Organization. Malaria - Pakistan. 2022. Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON413 (accessed March 2025).

31. Ahmed AI. Whole of Syria cholera outbreak situation report no. 13. 2023. Available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/whole-syria-cholera-outbreak-situation-report-no-13-issued-28-february-2023 (accessed March 2025).

32. Eneh SC, Admad S, Nazir A, et al. Cholera outbreak in Syria amid humanitarian crisis: the epidemic threat, future health implications, and response strategy - a review. Front Public Health 2023; 11: 1161936.

33. The Guardian. Cholera resurges in Syria after earthquakes hamper efforts to control outbreak. 2023. Available online at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2023/apr/21/cholera-resurges-in-syria-after-earthquakes-hamper-efforts-to-control-outbreak (accessed March 2025).

34. Osman M, Cummings KJ, Omari KE, Kassem II. Catch-22: war, refugees, COVID-19, and the scourge of antimicrobial resistance. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022; 9: 921921.

35. Häsler R, Kautz C, Rehman A, et al. The antibiotic resistome and microbiota landscape of refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan in Germany. Microbiome 2018; 6: 37.

36. Boukari Y, Kadir A, Waterston T, et al. Gaza, armed conflict and child health. BMJ Paediatr Open 2024; 8: e002407.

37. Shawish AA, Weibel C. Gaza children face acute water and sanitation crisis. UNICEF; 2017. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/stories/gaza-children-face-acute-water-sanitation-crisis (accessed March 2025).

38. UNRWA. UNRWA Situation Report #145 on the humanitarian crisis in the Gaza strip and the West Bank including East Jerusalem. UNRWA; 2024. Available online at: https://www.unrwa.org/resources/reports/unrwa-situation-report-145-situation-gaza-strip-and-west-bank-including-east-jerusalem (accessed March 2025).

39. World Health Organisation. GAZA hostilities 2023/2024 - emergency situation reports. WHO; 2024. Available from: https://www.emro.who.int/opt/information-resources/emergency-situation-reports.html (accessed March 2025).

40. Taha AM, Mahmoud H, Nada SA, Abuzerr S. Controlling the alarming rise in infectious diseases among children younger than 5 years in Gaza during the war. Lancet Infect Dis 2024; 24: e211.

41. Bhala N, Curry G, Martineau AR, Agyemang C, Bhopal R. Sharpening the global focus on ethnicity and race in the time of COVID-19. Lancet 2020; 395: 1673-1676.

42. Saifee J, Franco-Paredes C, Lowenstein SR. Refugee health during COVID-19 and future pandemics. Curr Trop Med Rep 2021; 8: 1-4.

43. Alemi Q, Stempel C, Siddiq H, Kim E. Refugees and COVID-19: achieving a comprehensive public health response. Bull World Health Organ 2020; 98: 510-510A.

44. Altare C, Kostandova N, OKeeffe J, et al. COVID-19 epidemiology and changes in health service utilization in Azraq and Zaatari refugee camps in Jordan: a retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2022; 19: e1003993.

45. Altare C, Kostandova N, OKeeffe J, et al. COVID-19 epidemiology and changes in health service utilization in Uganda’s refugee settlements during the first year of the pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022; 22: 1927.

46. Moura HSD, Berra TZ, Rosa RJ. Health condition, income loss, food insecurity and other social inequities among migrants and refugees during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. BMC Public Health 2023; 23: 1728.